Modified tarsotomy for the treatment of severe cicatricial entropion

- Select a language for the TTS:

- UK English Female

- UK English Male

- US English Female

- US English Male

- Australian Female

- Australian Male

- Language selected: (auto detect) - EN

Play all audios:

ABSTRACT PURPOSE To analyze the efficacy of modified tarsotomy for the management of severe cicatricial entropion. METHODS Twenty-seven eyelids of 18 patients who underwent modified

tarsotomy between March 2011 and July 2013 were retrospectively assessed. The data collected included patient demographics, etiology of cicatricial entropion, and surgical history. Outcome

measures included surgical success rate, preoperative and postoperative eyelid position, and surgery-related complications. RESULTS Mean follow-up time was 13.2 months (range, 6–25.4

months), and the success rate was 81.8% (22 of 27 eyelids). Complications included eyelid margin notching (_n_=1) and blepharoptosis secondary to avascular necrosis of the distal marginal

fragment (_n_=1), both were corrected by minor surgical intervention. CONCLUSIONS The study findings suggest modified tarsotomy is effective for the correction of severe cicatricial

entropion. SIMILAR CONTENT BEING VIEWED BY OTHERS LATERAL TARSAL STRIP PROCEDURE: COMPARISON OF ABSORBABLE SUTURES AND NON-ABSORBABLE POLYPROPYLENE SUTURE. DOES THE SUTURE TYPE MATTER?

Article 19 October 2023 RECURRENT UPPER EYELID TRACHOMATOUS ENTROPION REPAIR: LONG-TERM EFFICACY OF A FIVE-STEP APPROACH Article 24 November 2020 COMPARISON OF CLINICAL OUTCOMES OF

CONJUNCTIVO-MULLERECTOMY FOR VARYING DEGREES OF PTOSIS Article Open access 05 November 2023 INTRODUCTION Entropion is inward turning of lid margin resulting in ciliocorneal contact and

associated keratopathy. The causes for entropion may be congenital, involutional, or cicatricial. Cicatricial entropion is characterized by tarsoconjunctival scarring due to chronic

blepharitis, ocular cicatricial pemphigoid, Stevens–Johnson syndrome, trachoma, longstanding use of topical glaucoma eyedrops, or previous surgeries.1, 2 Other signs include trichiasis,

forniceal shortening and symblepharon formation. Cicatricial entropion is a challenging condition to manage and many surgical skills with variable success rates have been reported. Treatment

of cicatrical entropion requires optimizing the underlying systemic condition and surgical repair. Many surgical procedures have been reported with variable success rate, which means the

definitive method does not exist. Kersten _et al_3 described transverse tarsotomy and lid margin rotation as a simple and reliable treatment with a success rate of 94% for mild to moderate

cicatricial entropion, but a lower success rate (55%) for severe cicatricial entropion. The senior author (RCK) modified the transverse tarsotomy technique for severe cicatricial entropion,

and herein, we present the method and the results of modified tarsotomy with lid margin rotation. SUBJECTS AND METHODS The case notes of all patients with cicatricial entropion that

underwent modified tarsotomy and followed for at least 6 months at the Oculoplastic Service at the University of California, San Francisco between March 2011 and July 2013 were reviewed. The

study was conducted in accordance with the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act and the guidelines issued by the Committee for Human Research. The University of California,

San Francisco IRB qualified the study as exempt (IRB #13-11711). The study adhered to the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki. This study represents consecutive patients whose eyelids met

the definition of ‘severe cicatricial entropion’ at a tertiary teaching hospital, between March 2011 and July 2013. Severe cicatricial entropion patients were selected by case note review

and using preoperative photographs. Severe entropion was defined as ‘gross entropion with tarsal deformity and conjunctival scarring’.1 Causative factors, operation records, postoperative

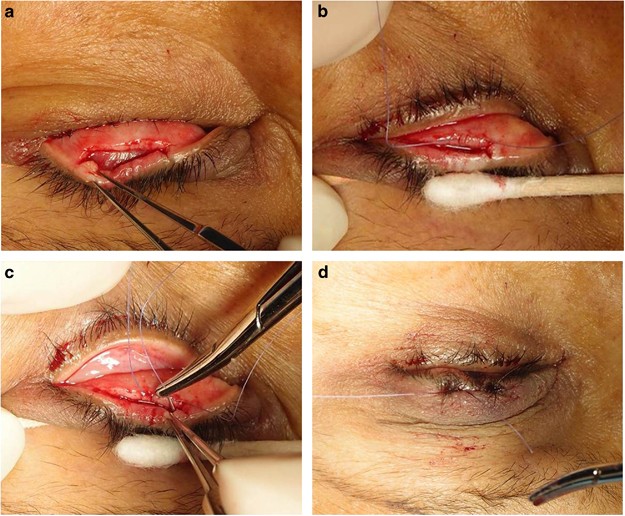

complications, and follow-up ophthalmological evaluation results were reviewed. Success was defined as no eyelash–ocular surface contact and complete eyelid closure. SURGICAL TECHNIQUE Under

monitored sedation and local anesthetic infiltration across the affected lid, a 4-0 silk traction suture was passed through the lid margin and used to evert the lid over a cotton-tipped

applicator. A Supersharp eye knife was then used to incise the posterior lamella at a point 2 mm proximal to the lid margin and a full thickness tarsal incision was made with a Westcott

scissors. The length of incision was about 2 mm longer than either side of the cicatrization. Two relaxing incisions were made medially and laterally at either ends of the transverse tarsal

incision toward the lid margin perpendicular to the initial transverse tarsal incision. Meticulous dissection was then conducted between the distal tarsal island and orbicularis oculi muscle

up to the lid margin, in order to allow full outfracture of distal tarsal fragment. Then rotational sutures with horizontal mattress 6-0 Vicryl sutures were passed through the proximal

tarsus and out just above the lash line. As many everting sutures as needed were employed to secure rotation of the distal tarsus (Figures 1 and 2). If slight overcorrection could not be

achieved, then the relaxing incisions were further anteriorized and edges secured with interrupted sutures. In the case of severe entropion related to ocular cicatricial pemphigoid, the

distal tarsal conjunctiva and eyelid margin were preserved to result in adequate outfracture and rotation. RESULTS The study included 27 eyelids (15 upper and 12 lower eyelids) of 18

patients (9 men and 9 women). Mean patient age was 68.7 years (range 42–90 years). Eleven patients had entropion of one eyelid. Two patients had unilateral upper and lower eyelid entropion,

three patients showed entropion of both upper eyelids, and one patient had entropion of both lower eyelids. One male patient had severe cicatricial entropion of all four eyelids. The causes

of severe cicatricial entropion were secondary to longstanding antiglaucoma drops usage in seven eyelids, chronic blepharoconjunctivitis in six, postsurgical in four (one

conjunctivo-mullerectomy, one lid reconstruction after basal cell carcinoma excision, one transconjunctival lower blepharoplasty, one ectropion repair), a chemical burn in three, a thermal

burn in two, Steven–Johnson syndrome in two, ocular cicatricial pemphigoid in two, and iritis associated with ankylosing spondylitis in one eyelid. Mean follow-up time was 13.2 months (range

6–25.4 months). Average extent of tarsotomy was 65.7% (range 33–100%) of horizontal eyelid length. Procedures combined with modified tarsotomy was upper blepharoplasty in one case. Success

was defined as the absence of eyelash–ocular surface contact in all directions of gaze and complete eye closure (Figure 3). Complete correction of entropion (the absence of eyelash–ocular

surface contact in all directions of gaze) was achieved for 22 (81.48%) of the 27 eyelids. Success rates by cause of entropion were as follows; 71.4% (5/7 eyelids) for secondary to

antiglaucomatous topicals, 66.7% (4/6 eyelids) for chronic blepharoconjunctivitis, 100% (4/4 eyelids) for postsurgical cases, 66.7% (2/3 eyelids) for a chemical burn, 2 of 2 eyelids for a

thermal burn, ocular cicatricial pemphigoid, and for Steven–Johnson syndrome, and 1 of 1 for iritis associated with ankylosing spondylitis. Five (18.52%) of the 27 eyelids, they were

considered as failure, developed a residual or recurrent symptom during follow-up and all 5 eyelids had residual trichiasis; 2 were treated by wedge excision and 3 by lid splitting and

anterior lamellar recession with a buccal mucous membrane graft. Two patients had complications who required surgical intervention. One patient developed medial side blepharoptosis secondary

to lid margin avascular necrosis requiring ptosis repair 6 months later. The other patient showed eyelid margin notching and partial ciliocorneal touch; after wedge excision the condition

did not recur. No cases of eyelid retraction, pyogenic granuloma, eyelid retraction, or overcorrection were encountered. DISCUSSION In this study, we investigated the success rate of

modified tarsotomy with lid margin rotation for severe cicatricial entropion. The most common cause of severe cicatricial entropion was secondary to longstanding antiglaucoma drops. The

success rate of our technique was 81.48% with 13.2 months mean follow-up time. Shrinkage of the posterior lamella of the eyelid, usually due to one of several conjunctival diseases, can

cause cicatricial entropion. Chronic blepharoconjunctivitis, Stevens–Johnson syndrome, herpes zoster, allergies, membranous or pseudomembranous conjunctivitis, and the long-term use of

certain eyedrops, such as, idoxuridine, dipivefrin hydrochloride, or antiglaucoma topicals, are the causes of cicatricial entropion in the United States, although worldwide the most common

cause of cicatricial entropion is trachoma.1, 2, 4–6 In the present study, the most common causative factor for cicatricial entropion was longstanding antiglaucoma eyedrops use. This

condition is called ‘pseudopemphigoid’ because light microscopy, electron microscopy, and immunofluorescence microscopy demonstrate no differences between ocular cicatricial pemphigoid and a

drug-induced pemphigoid-like condition. The infiltrations of inflammatory cells, such as, fibroblasts, macrophages, and lymphocytes, into conjunctival substantia propria are observed in

long-term users of antiglaucoma agents or idoxuridine.6, 7 Severe cicatricial entropion is one of the most challenging oculoplastic problems. Several surgical techniques have been introduced

for its treatment but success rates vary. The choice of surgical procedure for the management of eyelid cicatricial entropion is made based on considerations of severity and extent of

entropion, degree of eyelid retraction, fornix and tarsal involvement, and keratinization, eyelid margin distortion, and underlying disease progression. Surgical approaches can be broadly

classified into four categories: (1) grayline splitting of anterior and posterior lamellae; (2) posterior lamella lengthening; (3) eyelid margin rotation or eversion; and (4) a combination

of these three methods. Grayline splitting of anterior and posterior lamellae includes lamellar splitting with anterior lamella recession or excision, posterior lamella advancement, and

anterior lamella recession with posterior lamella advancement.8, 9, 10, 11, 12 However, this technique is not suitable in the presence of metaplastic lashes in the posterior lamella.

Posterior lamella lengthening requires the use of posterior and middle lamella grafts to restore a smooth surface for globe contact and therefore might take more time.13, 14, 15, 16, 17 Our

technique of tarsotomy is based on the principle of eyelid margin rotation or eversion. Transverse tarsotomy and lid margin rotation is a simple procedure that effectively repositions the

entropic lid margin without external incisions or grafting. Tarsotomy was first reported in 1903 by Ewing and is commonly used for trachomatous cicatricial entropion of the upper eyelid.18

Kersten RC _et al_3 applied the tarsotomy technique to nontrachomatous cicatricial entropion of both upper and lower eyelids, and reported a high success rate (94%) for mild to moderate

cicatricial entropion, but a lower success rate (55%) for severe cicatricial entropion. On the basis of their technique, we placed a horizontal incision paralleling the lid margin

posteriorly through the full thickness of conjunctiva and tarsus 2 mm proximal to the lid margin. Sharp dissection was done in the postorbicular fascial plane with a Wescott scissors to

release any scarring between anterior and posterior lamellae and to allow the eyelid to assume its natural position. A double-armed 5-0 Vicryl suture was then passed through the proximal cut

edge of the tarsus. Each arm of this suture was then passed distally between the orbicularis and tarsus of the distal lid margin fragment and brought out through skin just proximal to the

anterior lash line. To improve the success rate of tarsotomy for severe cicatricial entropion, we introduced a simple modification involving ‘two backcuts’ at both ends of the transverse

tarsotomy. These backcuts allow the distal tarsal fragment to move more freely and we believe they increase the success rate in cases of severe cicatricial entropion. The majority of reports

on the surgical success rate of cicatricial entropion did not divide patients according to severity and included all cases regardless of severity. However, success rates depend on disease

severity, for example, Kersten _et al_3 reported a tarsotomy success rate of 94% for mild to moderate cicatricial entropion, but of only 55% for severe cicatricial entropion. Furthermore,

relatively few studies have been undertaken on severe cicatricial entropion.11, 13, 14, 17 In the present study, we only included patients with severe cicatricial entropion, defined as

‘gross entropion with tarsal deformity and conjunctival scarring’ by Kemp and Collin.1 Entropion is considered mild if the tarsal plate appears grossly to be in a normal position but with

conjunctivalization of the lid margin and lash/globe contact only when gaze is directed toward the involved eyelid. Entropion is considered moderate when there is more significant

conjunctivalization of the lid margin approaching the base of the eyelashes and lash/globe contact is present in the primary position.1 A few studies have reported the surgical success rate

for severe cicatricial entropion. Kadyan _et al_ reported anterior lamellar excision with spontaneous granulation in seven ocular cicatricial pemphigoid patients was a simple, effective

procedure, but residual lashes in three patients.10 Wu _et al_11 reported lamellar splitting with eyelash resection procedure’s functional success rate was 90.5% for severe, recurrent,

segmental cicatricial entropion. However, this lamellar splitting technique is not suitable in the presence of metaplastic lashes in the posterior lamella. Goldberg _et al_ reported a shared

mucosal graft, based on posterior lamellar lengthening, was successful in 12 of 15 eyes (80%) with severe cicatricial entropion.14 Terminal tarsal rotation and posterior lamellar eyelid

reconstruction with acellular dermis allograft for severe cicatricial entropion was successful in 14 of 16 eyelids.13 This technique is similar to our technique except it is combined with

posterior lamellar lengthening with acellular dermis allograft but takes more time. Seiff _et al_19 reported a functional success rate of 100% for upper eyelid tarsal margin rotation and

extended posterior lamellae superadvancement, which is based on a combination of eyelid margin rotation and lamellar splitting of anterior and posterior lamellae. Yagci and Palamar reported

the long-term functional success of tarsal margin rotation and extended posterior lamellae advancement for upper eyelid cicatricial entropion due to end-stage trachoma was 100%.20 However,

although the functional success of this technique was reported to be 100%, it is complex and introduces the possibilities of excessive hemorrhage during dissection along Muller’s muscle and

fibrovascular adhesions between lamellae as Seiff _et al_ mentioned. Furthermore, it may not be cosmetically satisfactory nor appropriate for vertically shorter lower eyelid due to

possibility of tarsal buckling. Although the success rate of our modified tarsotomy is about 81%, and not 100%, it is much simpler to perform, produces cosmetically excellent results, and

can be applied for both upper and lower eyelid. Our technique’s success rate for severe cicatricial entropion was 81.48% (22 of the 27 eyelids). Five (18.52%) of the 27 eyelids, they were

considered as failure, developed a residual or recurrent symptom during follow-up due to residual trichiasis. Two of them were treated by wedge excision and three were managed by lid

splitting and anterior lamellar recession with a buccal mucous membrane graft. Complications after modified tarsotomy were few. We experienced one patient that developed medial side

blepharoptosis secondary to lid margin avascular necrosis requiring ptosis repair 6 months after surgery. This patient underwent upper blepharoplasty at the time of modified tarsotomy on the

medial side of the upper eyelid. Furthermore, in this patient, the marginal arcade may have been sacrificed during relaxing incisions after transverse tarsal incision and the peripheral

arcade may have been disrupted by blepharoplasty. Disruption of both marginal and peripheral arcades might have induced avascular necrosis and segmental blepharoptosis in the region of

tarsal fracture. This case cautions that combined procedures like blepharoplasty for possible peripheral arcade disruption should be avoided. The other patient showed eyelid margin notching

after modified tarsotomy and was managed by simple wedge excision. In conclusion, the described modified tarsotomy technique is a simple procedure with a reasonable success rate for severe

cicatricial entropion. We recommend this method be considered as a primary treatment option for severe cicatricial entropion due to its reliability, low morbidity, and repeatability.

REFERENCES * Kemp EG, Collin JRO . Surgical management of upper lid entropion. _Br J Ophthalmol_ 1986; 70: 575–579. Article CAS Google Scholar * Reacher MH, Munoz B, Alghassany A, Daar

AS, Elbualy M, Taylor HR . A controlled trial of surgery for trachomatous trichiasis of the upper lid. _Arch Ophthalmol_ 1992; 110: 667–674. Article CAS Google Scholar * Kersten RC,

Kleiner FP, Dulwin DR . Tarsotomy for the treatment of cicatricial entropion with trichiasis. _Arch Ophthalmol_ 1992; 110: 714–717. Article CAS Google Scholar * Burnstine MA, Putterman

AM, Sugar J . Cicatricial entropion caused by asymptomatic allergic conjunctivitis. _Orbit_ 1999; 18: 211–215. Article Google Scholar * Lass JH, Thoft RA, Dohlman CH . Idoxuridine-induced

conjunctival cicatrization. _Arch Ophthalmol_ 1983; 101: 747–750. Article CAS Google Scholar * D’Ostroph AO, Dailey RA . Cicatricial entropion associated with chronic dipivefrin

application. _Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg_ 2001; 17: 328–331. Article Google Scholar * Patten JT, Cavanagh HD, Allansmith MR . Induced ocular pseudopemphigoid. _Am J Ophthalmol._ 1976; 82:

272–276. Article CAS Google Scholar * Choi YJ, Jin HC, Choi JH, Lee MJ, Kim N, Choung HK _et al_. Correction of lower eyelid marginal entropion by eyelid margin splitting and anterior

lamellar repositioning. _Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg_ 2014; 30: 51–56. Article Google Scholar * Malhotra R, Yau C, Norris JH . Outcomes of lower eyelid cicatricial entropion with grey-line

split, retractor recession, lateral-horn lysis, and anterior lamella repositioning. _Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg_ 2012; 28: 134–139. Article Google Scholar * Kadyan A, Barry R, Murray A .

Anterior lamellar excision and laissez-faire healing for aberrant lashes in ocular cicatricial pemphigoid. _Eye_ 2010; 24: 990–993. Article CAS Google Scholar * Wu AY, Thakker MM, Wladis

EJ, Weinberg DA . Eyelash resection procedure for severe, recurrent, or segmental cicatricial entropion. _Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg_ 2010; 26: 112–116. Article Google Scholar * Baylis

HI, Silkiss RZ . A structural oriented approach to the repair of cicatricial entropion. _Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg_ 1987; 3: 17–20. Article CAS Google Scholar * Gu J, Wnag Z, Sun M,

Yuan J, Chen J . Posterior lamellar eyelid reconstruction with acellular dermis allograft in severe cicatricial entropion. _Ann Plast Surg_ 2009; 62: 268–274. Article CAS Google Scholar *

Goldberg RA, Joshi AR, McCann JD, Shorr N . Management of severe cicatricial entropion using shared mucosal grafts. _Arch Ophthalmol_ 1999; 117: 1255–1259. Article CAS Google Scholar *

Yoon MK, McCulley TJ . Autologous dermal grafts as posterior lamellar spacers in the management of lower eyelid retraction. _Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg_ 2014; 30: 64–68. Article Google

Scholar * Kakizaki H, Zako M, Iwaki M . Lower eyelid lengthening surgery targeting the posterior layer of the lower eyelid retractors via a transcutaneous approach. _Clin Ophthalmol_ 2007;

1: 141–147. PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Sakamoto Y, Nakajima H, Tamada I, Uchikawa Y, Kishi K . A backflip flap: a new surgical correction for severe cicatricial entropion.

_Plast Reconstr Surg_ 2010; 126: 179e–180e. Article Google Scholar * Ewing LE . An operation for atrophic(cicaricial) entropion of the lower eyelid. _Am J Ophthalmol_ 1903; 20: 39–40.

Google Scholar * Seiff SR, Carter SR, Tovilla y Canales JL, Choo PH . Tarsal margin rotation with posterior lamella superadvancement for the management of cicatricial entropion of the upper

eyelid. _Am J Ophthalmol_ 1999; 127: 67–71. Article CAS Google Scholar * Yagci A, Palamar M . Long-term results of tarsal margin rotation and extended posterior lamellae advancement for

end stage trachoma. _Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg_ 2012; 28: 11–13. Article Google Scholar Download references AUTHOR INFORMATION AUTHORS AND AFFILIATIONS * Department of Ophthalmology,

Gachon University Gil Hospital, Incheon, Korea M Chi * Department of Ophthalmology, University of California San Francisco, San Francisco, CA, USA M Chi, H J Kim, R Vagefi & R C Kersten

* Department of Ophthalmology, Permanente Medical Group, Hayward, CA, USA H J Kim Authors * M Chi View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * H J

Kim View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * R Vagefi View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * R C

Kersten View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar CORRESPONDING AUTHOR Correspondence to R C Kersten. ETHICS DECLARATIONS COMPETING INTERESTS The

authors declare no conflict of interest. RIGHTS AND PERMISSIONS Reprints and permissions ABOUT THIS ARTICLE CITE THIS ARTICLE Chi, M., Kim, H., Vagefi, R. _et al._ Modified tarsotomy for the

treatment of severe cicatricial entropion. _Eye_ 30, 992–997 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1038/eye.2016.77 Download citation * Received: 29 August 2015 * Accepted: 25 February 2016 *

Published: 22 April 2016 * Issue Date: July 2016 * DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/eye.2016.77 SHARE THIS ARTICLE Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content: Get

shareable link Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article. Copy to clipboard Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative