10 days with marlon brando | members only access

- Select a language for the TTS:

- UK English Female

- UK English Male

- US English Female

- US English Male

- Australian Female

- Australian Male

- Language selected: (auto detect) - EN

Play all audios:

In our conversations, the star showed a prescient mistrust of interactive media, then in its preinfancy. He told me about an experimental technology that allowed TV viewers to communicate

their reactions to a show in real time — and said the system had “many dangers”: “If I had the opportunity to press a button, and if that would somehow translate into a vote or an opinion

that would influence other people, it could be very destructive,” he reasoned. “Because after a day or two I might have seasoned my thoughts with reflection and found I made some critical

errors.” Brando also talked about the universal nature of storytelling, and why viewers are drawn to films with clear-cut heroes and villains. “People get so tired of sitting in the

in-between world” — that is, the real world, where questions of good and evil are more nuanced, he told me. “It’s such a relief to see something that’s good or for the devil.” With the

women’s movement in full swing, Brando shared his philosophy on the conflict between the sexes. “I think, essentially, men fear women,” he told me. “History is full of references to women

and how bad they are, how dangerous.” Having been raised by women, he speculated, men feel dependent upon women, and they fear that dependence. “We’ve all been guilty, most men, of viewing

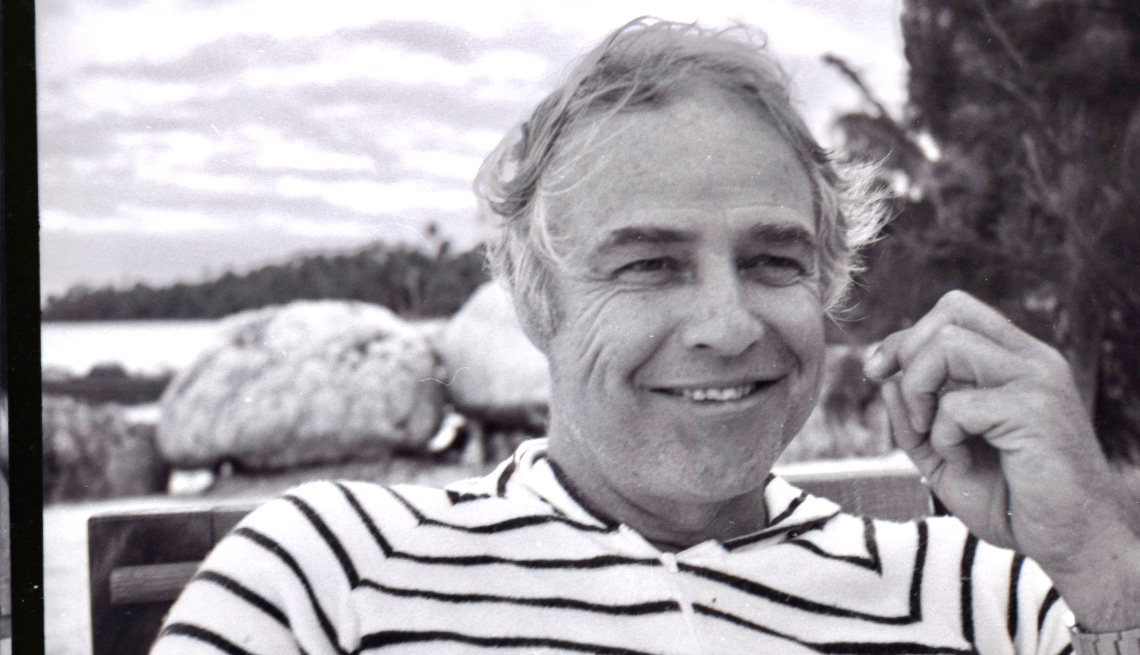

women through prejudice,” he confessed. “I always thought of myself not as a prejudiced person, but I find, as I look over it, that I was.” Marlon Brando starred as Vito Corleone in the 1972

film "The Godfather." CBS via Getty Images And yes, he did talk about the struggles of Native Americans. Brando had famously tried to draw attention to the issue in 1973, when he

learned he was the favorite to win a best actor Oscar for _The Godfather._ Rather than attend the ceremony, he sent an actress and activist named Sacheen Littlefeather to decline the award

on his behalf. His goal had been to protest discriminatory portrayals of Native Americans in Hollywood films, and to call attention to the Native American activists who were at the time

involved in a standoff with the federal government at Wounded Knee, South Dakota, over unfair and breached treaties. When we spoke five years later, Brando despaired of being able to rally

public opinion behind the Native American cause. “Nobody wants to think about social issues, social justice,” he told me. “Ask most kids about details about Auschwitz or about the manner in

which the American Indian was assassinated as a people and ground into the ground, they don’t know anything about it. And they don’t want to know anything. Most people just want their beer

or their soap opera or their lullaby.” (Brando might not be surprised to learn that it is only this year, 46 years after our interviews, that the first Native American woman, Lily Gladstone,

was nominated for a best actress Oscar.) A FEW YEARS BEFORE my interview with Brando, John Wayne had said some controversial things about Native Americans, including that he didn’t think it

was wrong to take America away from them because they “were selfishly trying to keep it for themselves.” When I asked Brando for his thoughts on those comments, he told me he would answer,

but he wanted to have what Wayne said in front of him when he did. In those days before you could pull up an old interview on your phone, we agreed to meet again back in L.A. for a follow-up

chat. For me, that was a bonus, because it would give me time to digest what had gone down on the island. A few months later, I was supposed to go to Brando’s house, when his assistant

called to ask where I lived. “Marlon will come to you,” she said. I wasn’t expecting that. Our house was a mess, and I quickly grabbed the dirty dishes in the sink and stuck them under the

cabinet. It only took Brando 15 minutes to pull into our driveway. The first thing he said was that he’d like to see what I’d written about him. No, I told him. That wouldn’t be journalism

if I let him have a crack at it. “Let’s get to John Wayne,” I said. We talked, not just about Wayne, whom he didn’t care for, but about so many other things that he hadn’t been willing to

talk about on the island. We even got into his using cue cards when acting because he didn’t like to memorize his lines. “Isn’t it distracting for the other actors?” I asked. “They’ve got

their lines down, and you’re reading yours off cue cards, or in the case of Maria Schneider in Last Tango in Paris, off her forehead.” During this part of our conversation, Brando would

arbitrarily mention book titles as he looked at me. I wasn’t sure why, until he said, “I’ve been reading the titles of the books on your shelves, and you haven’t noticed or been distracted.

You didn’t even know that I was doing that. I can do the same thing when acting. It’s more spontaneous.” When I asked him why he was so put off by winning the Academy Award for _The

Godfather,_ he said, “I don’t believe in awards of any kind. They are ridiculous. The optometrists are going to have Oscar awards for creating inventive, arresting, admirable, manufactured

eyeglass frames — things that hook on to the nose, ones that go way around under the armpit for evening wear. They should have an award for the fastest left-handed standby painter who’s

painted the sets with his left hand at great speed. And the carpenters union should have an award for somebody who can take a 3-pound hammer and nail two-by-fours together.” “Does being

labeled a method actor mean anything to you?” I asked, knowing how much he disliked talking about acting. “B-o-r-e. Bore,” he said. “Is that what a method actor does — to bore through to

the core of a character’s being?” “It bores through and goes beyond the frontiers of endurable anguish of interviews,” he said.