How to be a caregiver for someone with dementia

- Select a language for the TTS:

- UK English Female

- UK English Male

- US English Female

- US English Male

- Australian Female

- Australian Male

- Language selected: (auto detect) - EN

Play all audios:

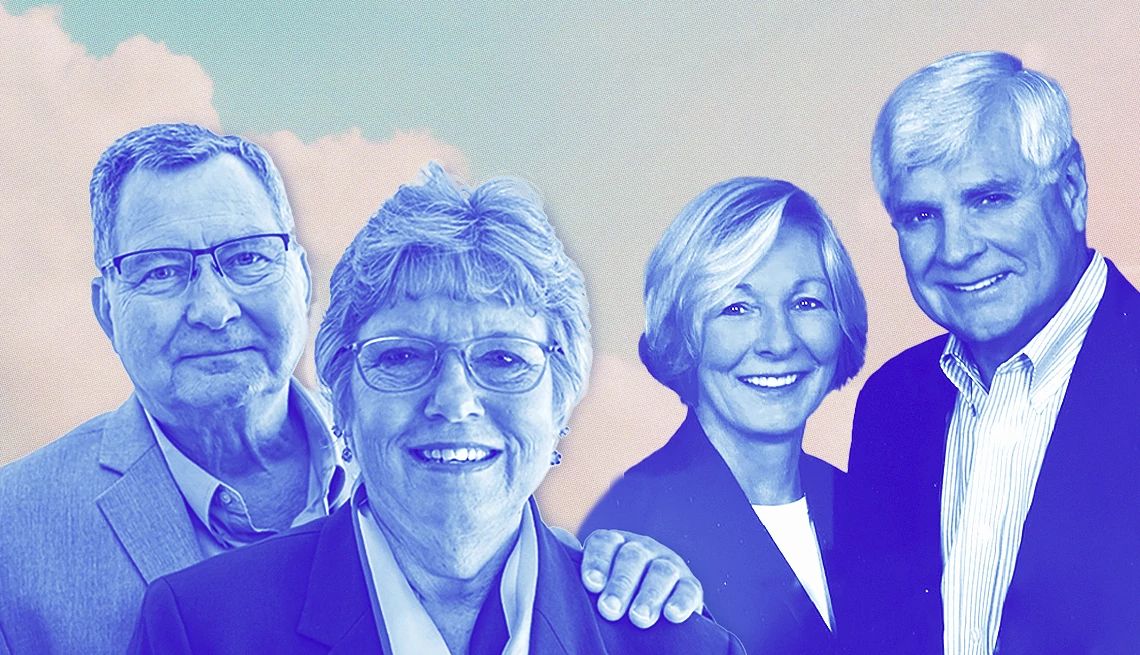

EARLY TREATMENT AND LIFESTYLE CHANGES MAY HELP For Bradley, a mother of four and grandmother of 12, getting diagnosed with early Alzheimer’s at age 56, was tough. She says a scan that

revealed beta-amyloid plaque buildup in her brain allowed her to enter a drug trial. She no longer takes the drug, aducanumab (which is being discontinued by its manufacturer), but says it

helped her — for one thing, her scans no longer show the plaques. “I’m doing very well,” she says, though “declining still a bit” in remembering recent events and finding words. She says her

doctor tells her the brain plaques will eventually return. Although there’s no cure for Alzheimer’s or other forms of dementia, prescription medicines can sometimes help manage symptoms.

Other medications, like the one Bradley took, target beta-amyloid and appear to slow cognitive decline in some people with early Alzheimer’s, according to the National Institute on Aging.

These drugs can have side effects such as swelling and bleeding in the brain. Drugs aren’t the only approach to early care. Phil Spanninger, 81, of Akron, Ohio, says that after his wife,

Janet, 80, was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s in 2012, they found that exercise and an active social life were the best medicine for her — and Janet’s neurologist agreed. At the time, they lived

in Montana, skied every day and spent a lot of time with friends, he says. He says he’s sure that lifestyle “helped stretch the disease out.” It was only when they were living a more

isolated life in Ohio during the COVID-19 shutdown of 2020, he says, that Janet suddenly declined. Today, she has advanced Alzheimer’s and lives in a memory care facility. CAREGIVER SUPPORTS

ARE GROWING In a recent survey by the Alzheimer’s Association, two-thirds of dementia caregivers said they had trouble finding resources and support. More than half said navigating the

health care system was hard. The survey confirmed that some kinds of help are in short supply: More than half of primary care providers who treat dementia patients said their communities had

too few dementia specialists. But “the variety of ways to get help now is greater than ever,” Edgerly says. One potentially big development: In July, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid

Services (CMS) launched an eight-year pilot program called GUIDE (Guiding an Improved Dementia Experience) to cover comprehensive services for Medicare recipients with dementia and their

unpaid caregivers. The program is underway at 96 locations and will expand to 390 on July 1, 2025. Participating providers, which include small doctor’s offices as well as large academic

medical centers, give patients and caregivers access to a 24/7 helpline and pair them with care navigators to locate services in their communities. The model “recognizes the importance of

the caregiver,” Moreno says. A key provision: $2,500 a year for respite care — temporary paid help — so caregivers can get breaks. Other insurers are starting to cover dementia care

navigation, Moreno says. Anyone can call the Alzheimer’s Association’s 24/7 helpline at 800-272-3900 to get free help with care planning and other needs, she says. Help may be closer to home

than many people realize, says Jennifer Crowley, a care manager in Kalispell, Montana. Your local Area Agency on Aging, she notes, can refer you to services that may range from training to

meal delivery. Some families, she adds, hire professional care managers, often called aging life care professionals, to help plan and advocate for their loved ones. Video: Son Uses TikTok to

Humanize Dementia Caregiving THERE’S HELP, BUT NO ‘COOKBOOK,’ FOR COMMON CHALLENGES As dementia progresses, caregiving typically gets more difficult, Edgerly says, and not just because your

loved one’s judgment, memory and reasoning decline. “They may not remember who you are,” she says, and “may not be able to express gratitude.” But, she adds, “there’s lots of people who’ve

gone down this road before, and lots of lessons have been learned.” Joining a caregiver support group can be a huge help, Spanninger says. He goes to one once a month, he says — mostly to

support “newbies.” There are tried-and-true strategies for day-to-day challenges, Crowley says. Most people with dementia do best with a consistent schedule, she says, especially if you put

the routine in writing, so others can follow it when you are out. Getting outdoors can be a balm, she says. “It’s really important to engage the person with dementia in as many daily

activities as possible,” she says, whether that’s folding laundry, emptying the dishwasher or doing a hobby they still enjoy. When it comes to particularly challenging behaviors — asking the

same question many times a day, hitting caregivers or wandering away from home — there’s rarely a “cookbook” solution, Kales says. She urges caregivers to see “behavior as communication”

and try to decode the message.