What to know about the ba. 2. 86 ‘pirola’ variant

- Select a language for the TTS:

- UK English Female

- UK English Male

- US English Female

- US English Male

- Australian Female

- Australian Male

- Language selected: (auto detect) - EN

Play all audios:

A highly mutated coronavirus variant that a few months ago was responsible for only a few COVID-19 infections in the U.S. is gaining traction, new data shows. According to the Centers for

Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), BA.2.86 (nicknamed “Pirola” on social media) now accounts for roughly 9 percent of cases in the U.S., up from 1.3 percent last month and 3 percent two

weeks ago. In some areas of the country, that share is larger; BA.2.86 is behind more than 13 percent of cases in the Northeast, for example, and the CDC says its presence is only expected

to increase, according to an update the agency posted on Nov. 27. However, despite its recent growth, health officials are not sounding the alarm just yet on the newly classified “variant of

interest.” Both the CDC and World Health Organization (WHO) say the public health risk posed by BA.2.86 is low at this time, based on the available evidence. What’s more, it’s expected that

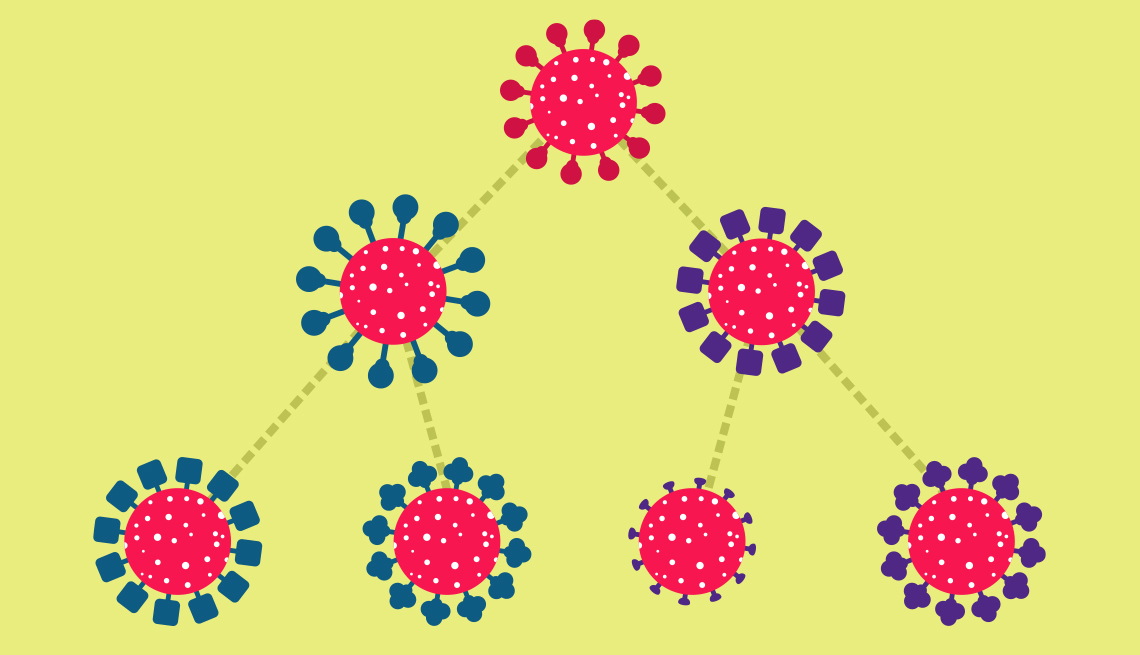

existing vaccines, treatments and tests will continue to work. WHAT PUT BA.2.86 ‘HIGH ON RADAR SCREEN’? BA.2.86 first grabbed the attention of health experts across the globe in late August

due to a striking number of genetic differences that set it apart from previous versions of the virus. All viruses change over time, including the one that causes COVID-19. These changes

can affect how contagious a virus is or how well it responds to treatment, according to the CDC, which is why scientists keep close tabs on the coronavirus’ evolution. What first concerned

scientists about BA.2.86, however, is that it has a lot of changes — there are more than 35 mutations relative to the omicron strains that have recently been circulating. According to the

CDC, that’s a difference that is more in line with those seen between the initial omicron variant and its predecessor, delta. The location of these mutations also warranted a closer look,

Andy Pekosz, a professor of microbiology at Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, told AARP in August. “A lot of those mutations are in areas where we know antibodies bind to the

spike protein,” which is what the virus uses to enter our cells, he said. “So that’s why that variant is really high on our radar screen.” Since the CDC’s initial risk assessment of BA.2.86

in August, however, the variant remained relatively uncommon in the U.S. It only started picking up steam in mid-October.