Reversing hearing loss with a cochlear implant

- Select a language for the TTS:

- UK English Female

- UK English Male

- US English Female

- US English Male

- Australian Female

- Australian Male

- Language selected: (auto detect) - EN

Play all audios:

How does it work? In a healthy ear, the cochlea’s hair cells transmit sound to the auditory nerve, but that’s impossible when the hair cells are injured. With a CI, the sound processor and

microphone on my ear collect sound and send it to the implant’s electrodes. They convey signals to the auditory nerve, which relays the message to my brain. The brain interprets the message

as sound — eventually. Two weeks after surgery, Chouery activated and programmed my implant. The moment of truth. She hit the equivalent of the “power on” button, and I heard my first new

sounds. Oh my. What sounds they were: roaring air, clangs, whistles and a mumble of unintelligible speech. My brain had to adjust — not my ear but my brain. We hear with our brains. The ear

converts sound to a signal that the brain interprets and understands. Would my brain accept the mechanical intruder? I had my doubts. My implant replaced all those thousands of hair cells

with just 22 electrodes, after all. In those early post-op days, I heard mostly noise. How could my brain do its job with so little information? Then, magically, it did. About two weeks

after activation, I was listening to a newscast. Until that night, the anchor, Lester Holt, sounded as he always had, because I heard him through my hearing aid, while my implanted ear

whooshed away like annoying background noise. That night, though, Holt’s voice began to sound odd, sort of tinny. I was hearing him through the implant as well as through my hearing aid! My

brain was adapting, translating the implant’s weird sounds into familiar language. The beginning of my new life! I was progressing, hearing more, but not quite normally. It takes time and

training to help the brain interpret the implant’s signals. I continued to work with Chouery on comprehension — focusing on distinguishing between words that sound alike, repeating simple

sentences, taking multiple-choice tests on what I had heard as I worked my way through online exercises. My hearing improved rapidly. Over the next several months, tests showed that my

understanding of sentences in my implanted left ear went from 6 percent before surgery to more than 70 percent — and on one test, to over 90 percent. Adjusting to the implant can take

patients up to a year, sometimes longer. Every experience is different. REGAINING SOUND My new reality? Conversations are back — no faking or withdrawing. I hear well in small

gatherings but not so great in crowded settings with a lot of ambient noise. Amplified sound remains difficult. But the sound of speech is now close to what it was before my hearing loss —

somewhat more robotic, but the voices of friends and family (yes, even Lester Holt) are fully recognizable. A new hearing aid in my better ear syncs with my implant. That improves my

general hearing and streams sound directly into both ears, which lets me converse by cellphone and enjoy videos, podcasts and audiobooks. All that was impossible before surgery. Music, a

more sophisticated sound than speech, is distorted for me. While intensive training helps some CI users with music, implants are designed for language and speech comprehension, not for

Beethoven. I miss Beethoven. I miss hearing as I did when I was young. But as we all learn as we age, life is a matter of trade-offs. I was cut off from the world around me. Now I am back

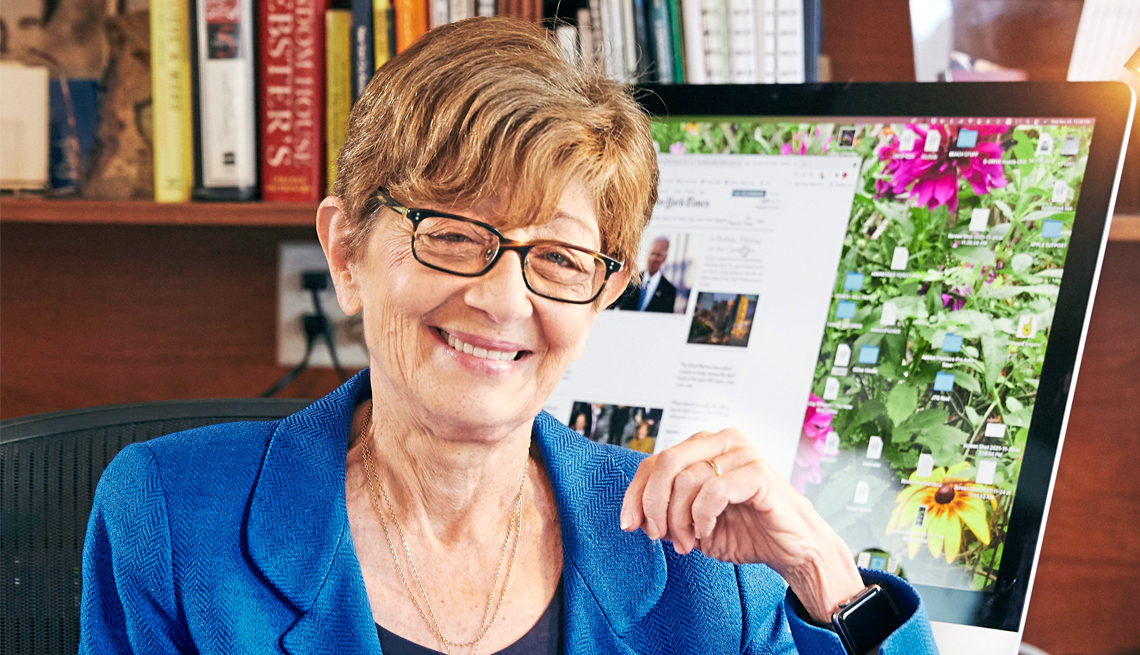

in the game. I’ll take it. _Joyce Purnick is an award-winning journalist and former columnist for _The New York Times_._