Innovations help imperfect organs work for transplants

- Select a language for the TTS:

- UK English Female

- UK English Male

- US English Female

- US English Male

- Australian Female

- Australian Male

- Language selected: (auto detect) - EN

Play all audios:

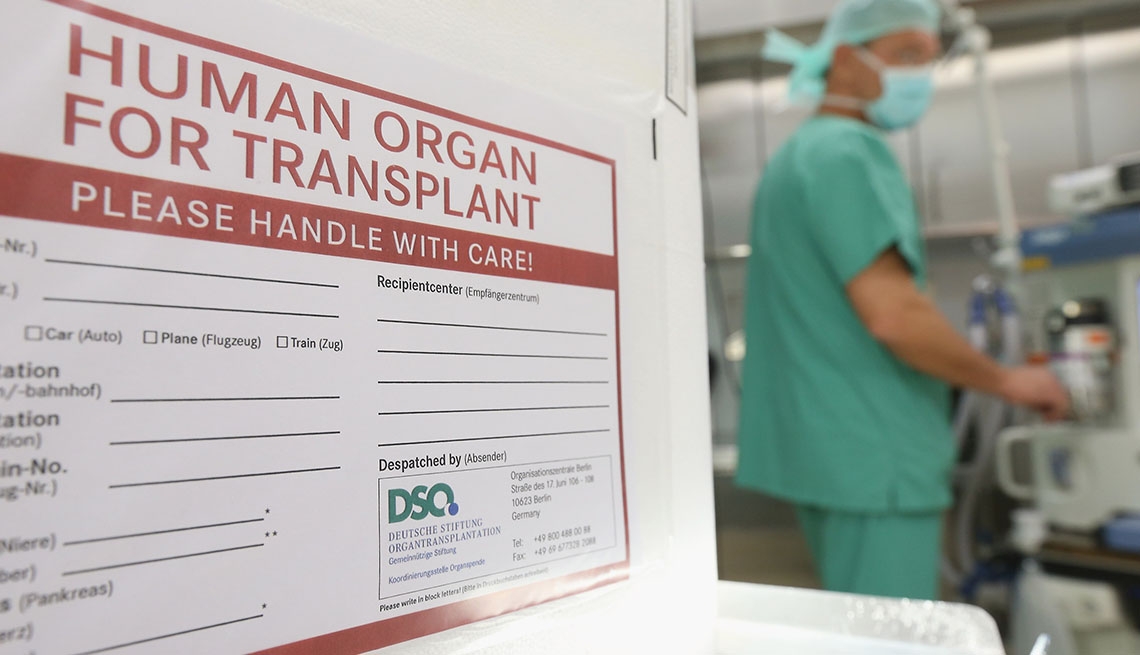

FOR EXPERT TIPS TO HELP FEEL YOUR BEST, GET AARP’S MONTHLY HEALTH NEWSLETTER. HEALING DAMAGED ORGANS Probably the biggest innovation paving the way for using marginal organs — and the

development the medical community is most excited about — is the development of “perfusion” devices that can rejuvenate lungs, hearts, kidneys and livers outside the body. Historically,

organs were removed from a donor, placed on ice and then raced to the recipient before they deteriorated too much. Now they can be hooked up to a machine that keeps them at body temperature

and functioning outside the body, giving doctors time to evaluate and, if necessary, repair them by flushing them with antibiotics or other solutions. Several types of devices for different

organs are undergoing clinical trials at medical centers across the U.S. Some have already been approved in Canada and Europe. At UCLA, where surgeons are testing a device that works on

livers, Ronald Busuttil, chief of liver and pancreas transplantion, called the technology “revolutionary.” “We take out the liver, hook it up to the machine, and organs that might not have

worked before are now working,” he says. He says he can actually see fat, for example, disappearing from the livers. At the Mayo Clinic in Jacksonville, harvested lungs are sent to United

Therapeutics in Silver Spring, Md., for rehabilitation through a process called ex vivo lung perfusion. There, they are hooked up to tubes and wires, flushed with specialized solutions and

put through a variety of tests before returning to Florida for transplant. “They're in this huge dome and they're breathing like regular lungs,” Leventhal says. “It's quite

amazing.” This year, that process will move to a new lung rehabilitation center in Florida. A joint effort of Mayo and United Therapeutics, the center won't just renovate lungs for Mayo

patients; it will provide rehabilitated lungs to transplant centers across the Southeast. "With this center, we think we can more than double the number of lung transplants and

significantly reduce the number of people dying on the wait list,” Leventhal says. Boestch, the Florida patient with lung disease, said it didn't take him long to recover from his

transplant, and by all accounts, it was a big success. Now age 73, he's back to doing the things he loves, such as exercising, playing golf, taking long bike rides and spending time

with family and friends. He said he didn't hesitate when he was asked if he wanted a rehabilitated lung, because he had done his research. "I knew those lungs are put through

rigorous testing, flushed with antibiotics, put under a load test and fully refurbished,” he said. “In fact, I felt like I was going to get an even better lung than what most people get —

and I believe that's what I have."