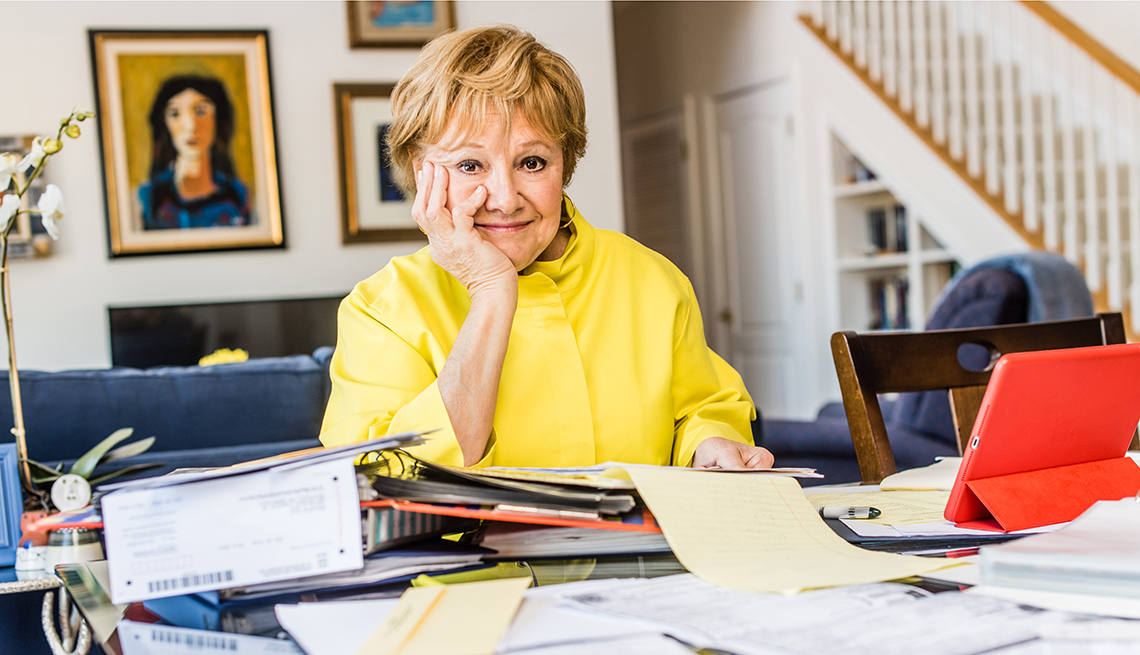

Left alone and at a loss - dealing with financial decisions after your spouse dies

- Select a language for the TTS:

- UK English Female

- UK English Male

- US English Female

- US English Male

- Australian Female

- Australian Male

- Language selected: (auto detect) - EN

Play all audios:

Our son, Jeremy, arrived the next day from California. Benjamin apologized for messing up everybody’s weekend. Ten days later, Benjamin was diagnosed with one of the most deadly forms of

brain cancer, glioblastoma multiforme. While dealing with treatment, he tried valiantly to get his papers in order. He even pulled together all of his passwords — a dozen different

combinations of letters and numbers — and put them in an email in that joint account. But he never told me what the email was called. After he died, I spent weeks combing through our online

inbox looking for the mystery message. He didn’t make it easy. Bad guys trolling would never have found it. I read message after message until I found the passwords in a file labeled

“numbers.rev.” I never did find the answers to his secret questions. His first pet? His childhood best friend? The first street where he lived? I’ve had to ask his brother. And I’ve had to

remember to tell my children the answers to mine. Looking back, I divide my ignorance into two categories: things I should have known and things I couldn’t have known. I should have known

the whereabouts of the documents for what we owned. Like many couples, we thought we had lots of time to arrange our affairs. At a time when it was all I could do to get dressed in the

morning, it was hard to hunt for bank records, deeds, insurance policies and investment records, let alone the passwords and secret questions that are the “open sesame” to access assets. One

of my first tasks as a widow was to file Benjamin’s will at the county courthouse. Our will was so old that it contained provisions for guardianship of our children, who are now grownups

and have children of their own. As I expected, we had named each other as beneficiaries of our IRAs and shared ownership of our home. But I didn’t realize that my husband had one small

investment account without a beneficiary. Because his account totaled less than $50,000, it was considered a small estate under Maryland law and probated quickly. THE CONVENTIONAL WISDOM TO

GRIEVING SPOUSES IS NOT TO MAKE MAJOR DECISIONS FOR A YEAR. WHAT THEY DON'T TELL YOU IS THAT YOU'LL BE BUSY DEALING WITH MINOR ONES. As part of the probate process, the estate was

advertised in the local paper. Within days I received a call from a man claiming to be from a Delaware law firm representing Benjamin’s creditors. I told him to put his claim in writing,

and I never heard from him again. I’ve since learned that some unscrupulous people check obituaries and immediately apply for credit cards in the name of the deceased. Luckily, my son had

notified the three major credit agencies right after Benjamin died so nobody could claim his identity. That was just the beginning of dealing with “death duties.” The conventional wisdom to

grieving spouses is not to make major decisions for a year. What they don’t tell you is that you’ll be too busy dealing with minor ones. Benjamin didn’t have life insurance. But he did have

an IRA, an investment portfolio, Social Security benefits, Medicare, a Medicare supplemental insurance policy and that small secret investment account. Notifying each government agency and

financial institution required a raft of phone calls, notarized forms and multiple meetings. No wonder I was advised to request at least a dozen original death certificates with raised

seals! If Benjamin and I had been better organized, I might have been spared some of the unpleasant surprises. But not all of them. When I called our insurance company to report my husband’s

death, they immediately raised my automobile insurance rate. Their agent explained that a single driver is a greater insurance risk than a couple sharing a car. Soon after, I notified our

primary credit card issuer. They immediately canceled my credit card. It turned out that Benjamin was the owner and I was merely a user. The bank representative explained that as a user, I

was not required to pay any balance owed, but they would take it up with the estate. If I overpaid, I would not get a refund. Since I was the representative of the estate, I paid the bill —

to the penny.