What is age discrimination and what does it sound like?

- Select a language for the TTS:

- UK English Female

- UK English Male

- US English Female

- US English Male

- Australian Female

- Australian Male

- Language selected: (auto detect) - EN

Play all audios:

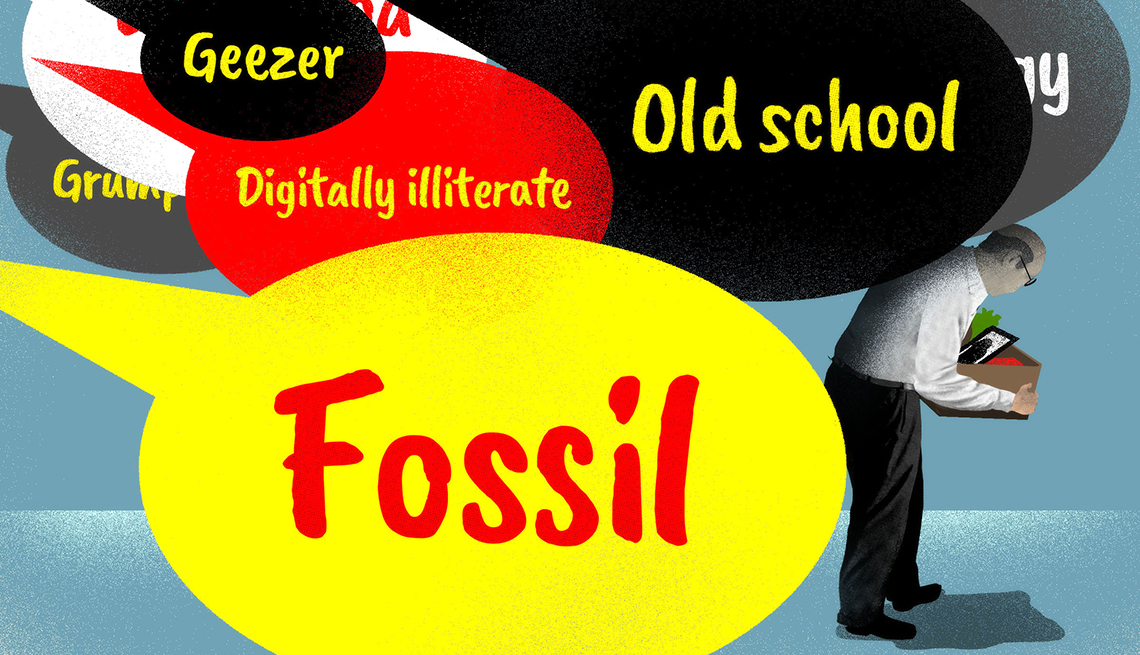

Weinmann returned to New York after the incident in Washington and got an advanced business degree. She now owns a consulting practice and advocates for older workers. That includes talking

to MBA alumni at New York University about the age harassment they can expect to face as they get older. The language of ageism is “pervasive” in business, she says. “People think that when

you get to a certain age, you’re not important.” ADEA AND FEDERAL LAWS Part of the reason age-biased language is so pervasive is that few employers train workers to view negative age-based

remarks as seriously as those that target race, gender or sexual orientation. But more telling are the roadblocks to seeking justice. While federal law says “it is unlawful to harass a

person because of his or her age,” that same law limits the damages victims can seek in federal court to things like back pay. In other words, in a federal court case, you can’t be

compensated for any mental anguish caused by verbal harassment, and your employer can’t be forced to pay punitive damages, no matter how blatant the abuse. That’s different from federal laws

covering discrimination based on race, gender, sex or disability, which allow for compensatory and/or punitive damages. Former AARP Foundation lawyer Laurie McCann recalls a case in which

an older worker’s desk was taken away from him to force him to quit or retire so younger colleagues could be seated. “The older worker who is standing in his office without a desk, what are

his monetary damages under federal law? None,” she says. “But he has still suffered harassment.” AARP and other organizations have pushed for a change in the federal Age Discrimination in

Employment Act (ADEA) to allow for compensatory and punitive damages, McCann says, but have not seen any progress.” One effective way to win an age-based harassment case at the federal level

is to prove that the employer intentionally created a work environment in which the harassment was so severe, hostile and pervasive it would cause a reasonable person to quit, McCann says.

In legal terms, that’s called “constructive discharge”; if your case meets this standard, you can sue for lost wages. An example of that is a case settled in 2019 with the assistance of AARP

Foundation attorneys against Ohio State University. Two instructors, now 64 and 68, in the College of Education and Human Ecology, alleged “an ongoing and unchecked pattern of harassing

conduct” by their supervisor, which included calling older workers “millstones” and “deadwood.” That created “working conditions so intolerable that a reasonable employee in either of their

circumstances would have been compelled to resign,” the women said in an EEOC complaint. Eventually, the women’s jobs were eliminated and they were forced to retire. The EEOC found the women

had faced “intentional age discrimination” in the workplace. Facing a potentially embarrassing legal battle, the university settled with the women for $765,000 in 2018, gave them their jobs

back and committed to conduct training sessions to prevent further bias. Still, such wins hardly keep pace with the amount of discrimination older workers experience, but they can be

achieved. Consider these recent decisions: * In December 2023, the EEOC ruled in favor of a 49-year applicant for a sales position who was rejected because the recruiters said the applicant

was “overqualified” and the company was “looking for someone more junior that can… stay with the company for years to come.” The company, Exact Sciences, agreed to pay $90,000 to settle the

claim. * Pharmaceutical giant Eli Lilly in 2023 agreed to pay $2.4 million to settle a nationwide class action lawsuit. The company’s “Early Career” hiring initiative, which lasted four

years, included goals intended to increase the number of younger workers Lilly employed. * In 2023, the medical device manufacturer Fischer Connectors, Inc. agreed to pay $460,000 to settle

a lawsuit from former human resources director. The company’s U.S. president asked the director “Why is [Fischer’s] workforce so old?” and “What age is the mandatory retirement [in the

U.S.]?”