The bengalis’ pioneering struggle for language rights – oped

- Select a language for the TTS:

- UK English Female

- UK English Male

- US English Female

- US English Male

- Australian Female

- Australian Male

- Language selected: (auto detect) - EN

Play all audios:

THEIR EIGHT-YEAR STRUGGLE FOR RECOGNITION OF BENGALI AS AN OFFICIAL LANGUAGE OF PAKISTAN LED TO THE DECLARATION OF FEBRUARY 21 AS INTERNATIONAL MOTHER LANGUAGE DAY BY UNESCO. UNESCO has set

February 21 as the International Mother Language Day to stress the importance of the mother tongue and multilingualism for achieving Sustainable Development Goals without leaving any section

behind. The Mother Language Day commemorates the struggle of the Bengalis of East Pakistan (earlier known as East Bengal and now as Bangladesh) for the recognition of their mother tongue

Bengali as an official language of Pakistan. In the late forties up to the middle of the fifties, the rulers of the new State of Pakistan including M.A.Jinnah were hell bent on making Urdu

the sole official language. This was based on the specious plea that Urdu is the quintessential “Islamic” language and therefore eminently suited to be the official language of a country

portrayed as the Homeland of the Muslims of the Indian sub-continent. The Bengalis not only challenged the identification of Urdu with Islam but also pointed out that Bengali was the

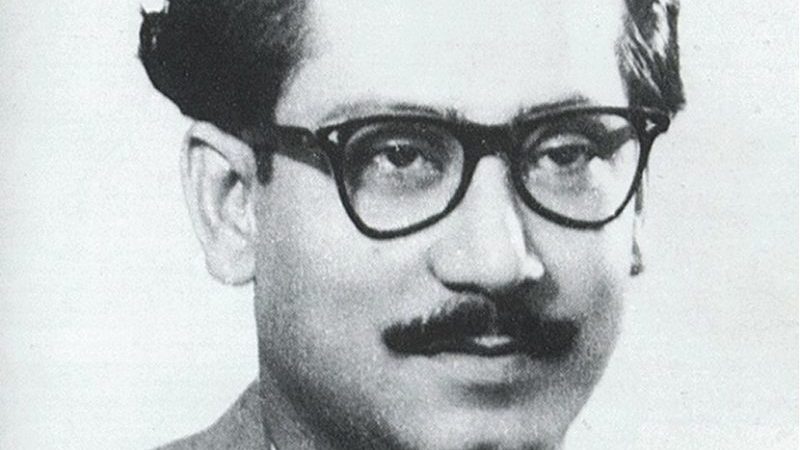

language of 56% of the population of Pakistan and therefore it deserved parity with Urdu. When these arguments were met with contempt by the ruling Muslim League, Bengalis, led

Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, Maulana Bashani and Dhaka University students, launched a sustained agitation from 1948 onwards. The highpoint of the massive and non-stop agitation was the firing on

student demonstrators in Dhaka on February 21, 1952, which resulted in many deaths. That day is observed as Language Movement Day or Martyrs Day and also as the International Mother

Language Day. Sheikh Mujibur Rahman writes in his “Unfinished Memoirs” that the incident on February 21, 1952 was the first in the world in which a people had sacrificed their lives for

their mother tongue. With Urdu as the sole official language, the Bengalis in Pakistan feared loss of status and opportunities to the dominant non-Bengali communities living in West

Pakistan, especially the Punjabis. Sure enough, immediately after the creation of Pakistan in 1947, political and economic power was grabbed by the more pushy West Pakistanis. It was East

Pakistan’s jute and other products which were earning foreign exchange for the country, but the money earned was being used mostly for the development of West Pakistan. The bureaucracy and

the armed forces were also dominated by West Pakistanis. It appeared that the erasure of Bengali language was part of the strategy to enslave the Bengalis. Muslim Leaguers who opposed

Bengali, had conveniently ignored the stellar role played by Bengali Muslims in the Pakistan movement. It was forgotten that the Muslim League was founded in Dhaka and Bengali Muslims

formed the bulk of the party’s supporters through the decades of struggle for the rights of Muslims in Hindu-majority India. The first person to demand that Bengali should be an official

language of Pakistan was a Hindu member of the Constituent Assembly, Babu Dhirendra Nath Dutt in February 1948. His demand was denounced by Muslim Leaguers from both the West and East wings

of Pakistan. But Dutt was backed by two non-mainstream organizations, the East Pakistan Muslim Students’ League and the Tamuddun Majlish. These organizations declared March 11 as “Bengali

Language Demand Day”. Dissident East Pakistani Muslim Leaguers like Sheikh Mujibur Rahman began to address their meetings. The students were particularly incensed when the Governor General

of Pakistan Mohammad Ali Jinnah declared twice in Dhaka on March 21, 1948, that Urdu would be the sole official language of Pakistan. On 8 April 1948, Khawaja Nazimuddin, Chief Minister of

East Bengal, moved a resolution in the East Bengal Legislative Assembly stating that Bengali should become the official language of East Pakistan. The resolution quelled protests in East

Pakistan, but Bengali continued to be relegated. Although the students were fired by enthusiasm, the general Bengali population was nonchalant. The euphoria over the creation of Pakistan

and liberation from Hindu domination was still there. And then there was the Muslim League’s propaganda about India’s hidden hand in the language movement. It was even said that the

agitators were students from Calcutta dressed up as Muslims. But no proof could be produced. All those arrested or killed were Bengali Muslims. Furthermore, many of those in the vanguard of

the Pakistan movement and the Muslim League like H.S. Suhrawardy, Maulana Bashani and host of others, were in the forefront of the language movement. One of the most important factors

contributing to the eventual success of the language movement was the alienation of the masses from the Muslim League. Muslim League rule both at the Center in Karachi (the then capital of

Pakistan) and in East Pakistan was oppressive, corrupt and intolerant after founder M.A. Jinnah died. His successor Liaquat Ali Khan was intolerant, as were Khwaja Nazimuddin and Nurul Amin

who headed the government in East Pakistan. Nazimuddin and others those who succeeded Liaquat Ali Khan as Prime Minister of Pakistan were dominated by bureaucrats who had little or no

consideration for the people. The isolated Muslim League began to persecute the opposition Awami League and other parties. Their leaders and cadres were thrown into prison, and the basic

needs of the population, including food, were neglected. Mujibur Rahman writes in his “Unfinished Memoirs” that people were wondering if this was the Pakistan they had so ardently sought and

fought for. Earlier, a ginger group led by Sheikh Mujibur Rahman had drawn up a manifesto which, apart from seeking parity for Bengali, demanded provincial autonomy with the Centre

retaining only Defense, Foreign Affairs, Communications and Currency. It was argued that autonomy was the only way to safeguard the Bengali language and Bengal’s resources from being looted

by outsiders. While autonomy was never granted by Pakistan, Bengali was recognized as a State language along with Urdu by the Constituent Assembly in 1954 and the National Assembly made it

law in 1956. However, the growing inequality between the East and West wings of Pakistan and the West’s refusal to recognize election results and allow Sheikh Mujibur Rahman’s Awami League

to form a government at the Center, led to a war which ended with the creation of a sovereign and independent Bangladesh in December 1971.