Painful Schmorl's node treated by lumbar interbody fusion

- Select a language for the TTS:

- UK English Female

- UK English Male

- US English Female

- US English Male

- Australian Female

- Australian Male

- Language selected: (auto detect) - EN

Play all audios:

Study design: A case report of painful lumbar Schmorl's node is presented.

Objective: To describe diagnostic evidence and the result of surgical treatment of a rare case of painful Schmorl's node.

Case report: A 55-year-old housewife was diagnosed with painful Schmorl's node of L3 by discography, which depicted leakage of the contrast medium into the L3 vertebra through a disruption

of the central part of the cranial end plate with concomitant back pain. Segmental fusion surgery was performed. Mechanical low back pain of the patient improved just after surgery.

Histologic examination demonstrated that fibrocartilaginous tissue herniated through a disruption of the superior end plate and forced into the vertebral spongiosa.

Conclusions: Painful Schmorl's node can be diagnosed by discography, which demonstrates an intravertebral disc herniation with concomitant back pain. Surgical treatment should be considered

in a patient with persistent disabling back pain. When surgical treatment is indicated, eradication of the intervertebral disc including Schmorl's node and segmental fusion are preferable.

Since an original report of Schmorl at early 1930s, Schmorl's node, which is defined histologically as a loss of nuclear material through the cartilage plate, the growth plate, and the end

plate into the vertebral body, is considered a common thoracolumbar lesion.1 Most of the established Schmorl's nodes are quiescent.2,3 There were, however, some reports of symptomatic

Schmorl's nodes.4,5,6,7,8,9,10 Although several attractive theories pertaining to an onset mechanism of Schmorl's node have been postulated, the etiology is unknown. The authors report a

rare case of painful Schmorl's node diagnosed by discography and treated by surgery, and indicate possible mechanisms of onset and treatment of choice.

A 55-year-old housewife experienced recurring low back pain for 8 years without any obvious causative episode. Low back pain following work deteriorated gradually and she had difficulty

continuing with household chores. During this time, there was no history of injury or significant exertional activity. Her family doctor referred her to our clinic. She had a past history of

surgical treatments for appendicitis at 19 years old and cholesteatoma at 43 years old. She had been treated for primary hypertension by a hypotensor for 5 years.

On presentation, she could not maintain a standing position for 30 min and could not walk more than 50 m because of low back pain. The pain, however, was relieved when she rested in bed.

Neurogenic intermittent claudication was not apparent. There was no limitation on a bilateral straight leg raising test. Neither sensory nor motor deficit of her lower extremities was

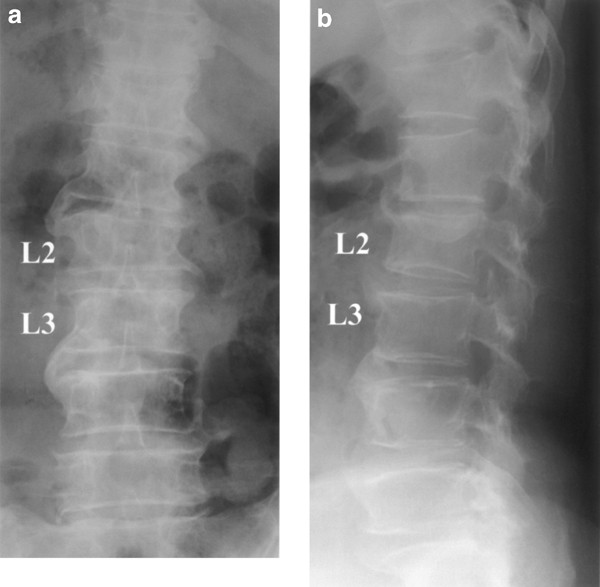

apparent. Vesicorectal functions and reflexes were normal. Plain spine radiograph revealed hyperostosis with the loss of physiologic lumbar lordosis. There were remarkable bone spurs at all

lumbar segments with bone bridges at L1/2 and L3/4 (Figure 1). Magnetic resonance imaging demonstrated Schmorl's nodules of L2 and L3, multiple disc degeneration, and compression fracture of

the T12 vertebra. The spinal canal was narrow at the levels of L4/5 and L5/S (Figure 2). As the pain source, we excluded lumbar canal stenosis at L4/5 or L5/S because there was neither

neurologic intermittent claudication nor neurologic deficit of the lower extremities. There was no knocking pain over the T12 spinous process or ‘high back pain’, suggesting that T12

compression fracture had already healed. We also excluded discogenic pain of L1/2 and L3/4 as a pain source because both segments had already fused (Figure 1). Thus, we performed discography

of L2/3 to determine whether the Schmorl's node of L3 was painful. A 21-gauge needle was inserted through a posterolateral approach under image control. She experienced severe concomitant

pain when 1 ml of contrast medium was injected. Leakage of the contrast medium into the L3 vertebra through a disruption of the central part of the cranial end plate was observed following

her concomitant back pain. There was no other remarkable annular tear (Figure 3). Based on these clinical and radiologic findings, the L2/3 level was considered to be the most possible pain

source among the radiologic lesions (Figure 2). Furthermore, because the L2/3 did not show any remarkable annular disruption, the Schmorl's node of the L3 vertebra was considered as a

causative lesion.

Plain radiographs showing hyperostosis with remarkable bone spurs at all lumbar segments and bone bridges at L1/2 and L3/4. (a) Anteroposterior view and, (b) lateral view

Magnetic resonance imaging demonstrates Schmorl's nodules of L2 and L3, multiple disc degeneration, and compression fracture of T12 vertebra. Spinal canal is narrow at the levels of L4/5 and

L5/S

Discogram demonstrating leakage of the contrast medium into the L3 vertebra through a disruption of the central part of the cranial end plate. She experienced severe concomitant pain when 1

ml contrast medium was injected. There is no remarkable annular tear

At surgery, the left lateral aspect of L1/2–L3/4 was exposed through a retroperitoneal approach. Osteophyte formation was remarkable at all segments exposed. The osteophytes were united at

L1/2 and L3/4. L2/3, however, demonstrated segmental motion. Segmental vessels of L2 and L3 were severed following ligation. The L2/3 intervertebral disc was excised. The nucleus pulposus

was degenerated with black discoloration. The cranial part of that L3 vertebra including Schmorl's node was removed en bloc using an osteotome. There was a cleavage 5 mm in length at the

central part of the L3 cranial end plate, through which the disc material protruded into the L3 vertebra. Excessive osteophytes were excised. We performed L2/3 fusion using a titanium mesh

cage with an autogenous iliac bone graft and Z plate (Medtronic Sofamore Danek USA, Memphis, TN, USA) (Figure 4). A sagittal section of the removed specimen stained with hematoxylin–eosin

demonstrated that fibrocartilaginous tissue herniated through a disruption of the superior end plate and was forced into the vertebral spongiosa (Figure 5).

L2/3 fusion was performed using a titanium mesh cage with an autogenous iliac bone graft and Z plate

Histologic examination. A sagittal section stained with hematoxylin–eosin demonstrates that fibrocartilaginous tissue herniated through a disruption of the superior end plate and forced into

the vertebral spongiosa (original magnification 1 × 2.5

Her mechanical low back pain was dramatically improved just after surgery. She was able to stand straight by postoperative day 4 and discharged 1 month after surgery without any support. On

the final follow-up 2 years after surgery, she did not complain of any difficulty with household chores.

Since Schmorl's description of intravertebral disc herniation,1 this radiographic finding has been reported in cases among a wide range of ages with congenital or developmental defects of

the cartilaginous end plate, various forms of metabolic bone diseases, neoplastic disease, degenerative disc disease, trauma, or lesion of unknown origin.4,5,6,8,11,12,13,14,15,16 While

Schmorl's node is usually considered asymptomatic,11 some authors reported acute onset of low back pain associated with the lesion.4,5,6,7,8,9,10 In the present case, discography of the L2/3

prior to surgery demonstrated an intravertebral disc herniation into the L3 vertebra through a disruption of the cranial end plate with concomitant back pain, suggesting that Schmorl's node

is a possible source of back pain (Figure 3). Although discography has been considered asymptomatic in quiescent Schmorl's node or in the so-called ‘limbus’ vertebra,17 it is the

examination of choice to diagnose ‘painful’ Schmorl's node as reported previously.4,7,9 In addition to the result of discography, intervertebral fusion of L2/3 dramatically improved low back

pain in the present case, suggesting that segmental motion contributed to generate the back pain related to the Schmorl's node. The histologic origin of the pain is, however, unknown.

McFadden and Taylor18 demonstrated that the specimens with Schmorl's nodes had a significantly greater proportion of disc marrow contacts than did the normal vertebrae. We also confirmed

that the intravertebral disc hernia directly contacted with the marrow of the vertebra (Figure 5). This suggests that disc herniation into the vertebral marrow irritates an intravertebral

nociceptive system,19 generating low back pain during spinal motion.

Persistent remnants of original nutritive vascular canals20 or ossification gaps corresponding to a perforation of the cartilaginous plate11 within the vertebral body are suggestive of

correlation with end plate weak spots, representing a route for the early formation of intravertebral nuclear herniations. In addition to the developmental factors, trauma and over load are

considered to contribute to the onset of symptoms of Schmorl's node.4,7,8,21,22,23,24,25 The relation between Scheuermann's disease and Schmorl's node implies contribution of developmental

and traumatic factors to generate Schmorl's node.26,27,28,29 Furthermore, the incidence of Schmorl's node in athletes is higher than in nonathletes.30,31,32,33 These clinical manifestations

suggest the importance of mechanical factors burdening the immature spine.

Since the end plate is a weak part of a spinal segment, the nucleus pulposus often disrupts the subjacent end plate and migrates into the vertebral spongiosa following exogenous

force.24,34,35,36,37 Expansive pressure of the nucleus pulposus is greatest in young persons because of the turgor present within the nucleus. This might account for the rapidity of

Schmorl's node formation in the central part of end plate in these individuals. In older persons, turgor decreases with the loss of fluid in the nucleus, and herniations occur more gradually

in the peripheral part because the normal stresses are transferred primarily by the annulus toward the periphery of the end plate.11,38 In the present case, discography demonstrated that

the grade of disc degeneration was not severe because the contrast medium was contained in the center of the disc except for the part of Schmorl's node (Figure 3). Furthermore, both adjacent

intervertebral discs were fused spontaneously, leading to stress concentration on the middle segment. These findings suggest that increased intradiscal tension and the stress concentration

contribute to bring about the intravertebral disc herniation into the adjacent vertebra.

There is no consensus on surgical treatment for Schmorl's node. Tsuji et al3 suggested that Schmorl's node was age independent, with a regressive or self-limiting nature. Smith also reported

a case with self-limiting back pain.5 On the other hand, there are patients who suffer from disabling pain due to Schmorl's node notwithstanding conservative treatment as in the present

case. Such patients might be the most difficult to treat. Improvement is slow and in some patients, who are severely disabled by persistent pain, it might be necessary to consider surgical

intervention and spinal fusion.7 When surgical treatment is indicated, the authors believe it is better to include eradication of intervertebral disc including Schmorl's node and segmental

fusion.

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content: