A survey of hygienists qualifying from the liverpool school of dental hygiene 1977–1998

- Select a language for the TTS:

- UK English Female

- UK English Male

- US English Female

- US English Male

- Australian Female

- Australian Male

- Language selected: (auto detect) - EN

Play all audios:

ABSTRACT OBJECTIVES To analyse the working patterns of all those who qualified from the Liverpool School of Dental Hygiene over a 20-year period. To assess the proportion who give up

practice, the degree of part-time work, career breaks, job satisfaction, availability of continuing professional education etc. METHOD A questionnaire sent to all 226 hygienists who

qualified from the School between 1997 and 1998, whether still enrolled as dental hygienists or not. Results Responses were received from 83% of whom 89% were still working as hygienists,

the majority in general practice. 46% had taken an employment break, mostly for maternity reasons but a significant number for other reasons. Around 80% expressed good job satisfaction.

Although there is a high level of part-time work, especially after career breaks, few had experienced difficulty in finding employment. One third of respondents considered that the

availability of continuing professional education was 'poor' or 'very poor'. CONCLUSIONS The great majority of hygienists enjoy good job satisfaction and work in more

than one general dental practice. Comparisons suggest that they continue to work in their chosen career at least as much as female dentists do in theirs. The reasons for this are thought to

be that hygienists tend to be recruited from the ranks of highly motivated, mature dental nurses and that the profession lends itself to part-time work which can be combined with family

commitments. There are perceived deficiencies in the availability of continuing professional education, which may be remedied by the development of distance learning packages and Section 63

type courses designed specifically for them. You have full access to this article via your institution. Download PDF SIMILAR CONTENT BEING VIEWED BY OTHERS THE DELIVERY OF DENTAL CARE TO

OLDER ADULTS IN SCOTLAND: A SURVEY OF DENTAL HYGIENISTS AND THERAPISTS Article 14 August 2020 A SURVEY TO EXPLORE THE MOTIVATION, SCOPE OF PRACTICE, JOB SATISFACTION AND TIMINGS OF

PROCEDURES UNDERTAKEN BY DENTAL NURSES WITH ADDITIONAL DUTIES AT ONE NHS TRUST Article Open access 07 May 2025 FACTORS INFLUENCING DENTAL TRAINEES' CHOICE OF TRAINING PROGRAMME AND

WORKING PATTERNS: A MIXED-METHODS STUDY Article 26 March 2021 MAIN Effective delivery of healthcare involves numerous different factors, not least of which are the selection and training of

the most appropriate personnel for the job and the provision of an attractive working environment once qualified. The dental profession is fortunate in that there are ample numbers of young

people who wish to train as dentists and hygienists. Nevertheless, the training schools have a responsibility to monitor their methods of recruitment to ensure that their students not only

are able to complete their course of study but also that, once qualified, they will have the aptitude and motivation to pursue their chosen profession for a substantial period afterwards and

assist its development. Although we have seen an increasing trend for the proportion of females applying for places as dental students in UK dental schools (Matthews and Scully)1 the

reverse has not been the case for dental hygienists. UK schools of dental hygiene continue to receive the great majority of their applications from dental nurses. This is despite the current

provision for direct entry for those with GCE 'A' level passes. The dental hygiene profession has traditionally been thought of as an ideal career progression for dental nurses

who can combine part-time work with family responsibilities. Also, dental nurses comprise a pool of highly motivated personnel who are very familiar with the nature of the job and its

demands. The extent to which family or other commitments affect the professional life of hygienists in terms of part-time employment and return to work is unclear. In 1988 a survey was

conducted of students qualifying from the Liverpool School of Dental Hygiene which aimed to analyse their career patterns over a 10-year period.2 The present paper has similar objectives and

includes the same subjects as well those who have qualified since 1988. The 1988 survey indicated that 22% of the subjects were not working as dental hygienists and the majority of the

remainder worked part time, citing family commitments as the main reason. One of the aims of this study was to assess whether there has been a return to work as dental hygienists after

possible reduction in family commitments, as well as to assess job opportunities, access to continuing professional education and job satisfaction. MATERIALS AND METHOD The Liverpool School

of Dental Hygiene attempts to maintain a comprehensive database of the current addresses of all its ex-students, whether they are working as hygienists or not, in order to maintain social

contact, to distribute information on refresher courses and to send an annual newsletter. The newsletter distributed to all 226 alumni (all female) in December 1998 included a questionnaire.

The contents of the questionnaire are summarised in Tables 1 and 2. As an incentive for the return of completed questionnaires all those returning their forms by the end of January 1999

were entered in a draw for a cash prize. A reminder was sent to non-respondents in February 1999 and, where necessary, a second reminder was sent later that month, after ascertaining their

most up-to-date addresses from the 1999 Roll of Dental Hygienists as published by the General Dental Council of the UK on the internet. RESULTS Replies were received from 188 of the 226

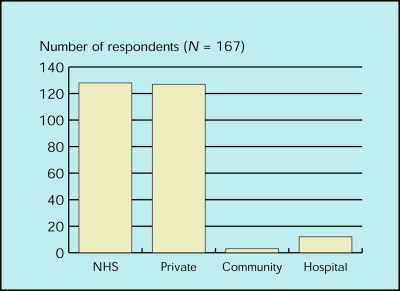

alumni, a response rate of 83%. Of the respondents, 167 (89%) were working as hygienists and a further 10 (5%) were working in some other paid employment. Four of these (2% of the total)

were using some of the knowledge or skills gained from their training as hygienists, as, for example, health promotion manager, dental representative, school matron. Only 11 (6%) were not

working. The great majority of practising hygienists were working in NHS practice, private practice, or a combination of the two. Only 9% were working in the hospital or community services

(Fig. 1). Thirty-four respondents (18%) worked exclusively in NHS practice, a similar number (17.5%) exclusively in private practice and 94 (50%) in a combination of the two. Subjects were

asked to indicate the average number of hours they work per week as hygienists in seven categories (not working, 1–8 hours, 9–16 hours, 17–24 hours, 25–32 hours, 33–40 hours and more than 40

hours). For convenience, the results have been converted to 'average days' of 8 hours, although it is realised that the hours may have been worked as fewer longer days or more

shorter days. Figure 2 shows that 67 respondents (36%) work the equivalent of five or more days per week (35+ hours). Figure 3 shows that 50 (30%) of the respondents working in general

dental practice work in only one practice, 36% in two, 21% in three and 13% in four or more. The average number of practices worked in by each hygienist was 1.73. When subjects were asked if

they had taken an employment break of 3 months or more, 86 respondents (46%) indicated that they had. Of these, 74% indicated that the break was for maternity reasons. In only one instance

was an inability to find a job given as the reason for the career break. Reasons given by the remainder included a 'desire to travel' (3), 'fancied a change',

'didn't want to work while children under 5', 'looking after children' (2), job or career change (5), 'abroad and unable to work', 'time to be with

husband and animals', 'training for another career' (eg podiatry, dental therapy), 'work in family business', 'illness (7), 'monotony/stress',

'teach in summer camp/USA', 'University course (3), 'needed a change'. When asked about job satisfaction on a five point scale, 83% stated that they had good or very

good job satisfaction (79% of those still working as hygienists) whereas only 9.6% stated poor or very poor (the same percentage as those still working as hygienists). Twenty-nine

respondents did not answer this particular question (Fig. 4). The questionnaire listed five factors which are commonly perceived to enhance job satisfaction and a further five which may

serve to depress job satisfaction. (Table Table 2). The statements were taken from the UK National Survey of Dental Hygienists.4 Respondents were invited to indicate any five of the ten

statements which they thought particularly applied to them. On average, they marked 3.4 items from the left-hand list and 1.36 items from the right-hand list, reinforcing the view of good

job satisfaction amongst the majority of these hygienists. Table 3 shows the number of responses in each category in ranking order. The majority of respondents found it easy or very easy to

find employment (72%). Only 10% reported any difficulty (Fig. 5). In connection with the availability of continuing professional education, 46.5% considered it to be good or very good,

whereas 33.5% considered it to be poor or very poor (Fig. 6). This survey attempted to make a retrospective analysis of the varying amounts of time worked as a hygienist over the

individual's practising career. The results show that in the first 4 years after qualification the average hygienist worked for the equivalent of 33 or more hours per week (4 or more

days). By the definition of Scully and Matthews,3 this is full time. The amount of time worked then reduced to about 3 days per week on average until the 7th year after qualification,

thereafter remaining more or less unchanged (Fig. 7). DISCUSSION A major problem in this kind of study is the avoidance of bias. This may arise because the non-responders may contain a

higher proportion of those who have left practice. Also, most comparable surveys have only included hygienists or dentists who are enrolled or registered with the GDC,3,4 therefore missing

those individuals who have given up practice and ceased to be enrolled or registered. It is thought that the inclusive nature of this survey, together with its high response rate (83%)

enhances the validity of the data produced, even though the num bers surveyed are relatively small and limited to Liverpool alumni. This response rate is comparable to that of Matthews and

Scully's survey of registered dentists (78%)3 and considerably better than the national survey of hygienists in 1994 (48%).4 The majority of dental hygienists are female, the reason

being that, traditionally, recruitment to the profession has been largely from the ranks of dental nurses who have been able to see the work of a hygienist at first hand and see it as career

progression and a secure, adequately paid job with the opportunity for part time work, if required. Recently, dental hygiene courses have been recognised as higher education and a dual

entry system has been introduced, ie direct entry from school with two 'A' level passes or entry from the ranks of dental nurses having a nationally recognised dental nursing

certificate. Nevertheless, the majority of applicants are still dental nurses, an increasing proportion of whom also having 'A' levels. This provides a large pool of highly

motivated individuals from which to choose future dental hygienists. In the 1988 survey of Liverpool dental hygienists, 78% were recorded as still working as dental hygienists and dental

health educators. This has increased to 90% in the current survey. Also, the average number of practices which each hygienist works in has dropped from 2.24 to 1.73, suggesting that that

they are finding it easier to gain employment without having to split their working week among so many different practices. The degree of job satisfaction remains similar between the two

surveys (80.5% expressing satisfaction in 1988 against 83% in 1999). A high proportion of the respondents (46%) had taken a break of three months or more from work. In the majority of cases

this was for maternity reasons. A relatively small number chose to remain at home to look after small children. Another reason frequently given for the break was a desire for a change in

career, perhaps to obtain other qualifications, often in a health related field. Some wanted a break simply to spend more time at home or to travel. How much this reflected the stressful

nature of the job is difficult to determine. Nor is it possible to deduce from the information received, whether occupational factors were responsible for the illnesses mentioned by seven

hygienists (3.7% of respondents) who gave this as the reason for a break of 3 months or more. The results of this questionnaire did not support the view which is sometimes expressed but with

little objective evidence, that there is a high level of dissatisfaction among hygienists. This survey, as well as those conducted by Bickley in 1994 and Hillam in 1988, indicates that

dental hygienists in the UK enjoy good job satisfaction and records a larger number of positive factors in connection with their work than negative ones. Also, they continue in employment at

least as much as female dentists. Only 6% recorded any difficulty in finding work which reinforces the perceived opinion that hygienists are in a 'buyers market' and therefore

able to command high salaries, at least in some parts of the United Kingdom. Although there were no financial questions in the questionnaire it is a reasonable assumption that high salaries

would improve satisfaction ratings. In the open questions, no respondent indicated lack of reward as being a source of dissatisfaction. On the other hand when the hygienists were invited to

indicate any negative aspects associated with their job, 73 (39%) said 'insufficient time allowed for appointments' and 69 (37%) said 'the repetitiveness of the job'

which could be said to reflect the financial constraints under which hygienists find themselves obliged to work. This was especially stressed by those working in NHS practice. While 46.5% of

respondents considered the availability of continuing professional education (CPE) to be 'good' or 'very good', 33.5% considered it to be 'poor' or 'very

poor'. Meetings arranged by the British Dental Hygienists' Association and its regional groups were particularly commended by some hygienists but others mentioned lack of

facilities in their own areas. It should be remembered that hygienists do not have a centrally funded scheme similar to Section 63 courses for dentists and the costs of attending courses

have to be borne by themselves or by their employing dentists. Most schools of dental hygiene organise refresher courses from time-to-time but without a network of regional tutors, the

location of these is not suitable for many of the more remotely placed hygienists. With the current development of the professions complementary to dentistry and the increasing realisation

of the need for CPE in all areas of employment, it is clear that more needs to be done to improve these facilities for dental hygienists. One way of improving this situation would be the

development of distance learning packages. This would be especially beneficial for those hygienists working in areas remote from a teaching centre. In comparison with the 1988 survey, there

is some indication that hygienists are finding it easier to gain employment immediately on qualification. This is shown by the fact that nearly all work full time from the time of

qualification and in fewer practices than 10 years ago. There tends to be an increase in part-time work and career breaks, mostly for maternity and child care reasons. It is difficult to

achieve direct comparison between this and other surveys of hygienists and dentists because the latter have been addressed only to people still registered with the GDC, whereas this survey

was addressed to all hygienists who had qualified at the Liverpool school. However, there is no indication that hygienists have a greater 'drop out' rate compared with other

professions. Indeed, this group compared very favourably with the study of registered male and female dentists by Matthews and Scully which showed that only 46% of the females were working

for 4 or more days per week.3 Nevertheless, this survey does show that once hygienists have given up work, or reduced the number of hours worked, they rarely go back to work full time. It

would appear that there is sufficient satisfaction in combining part-time work with caring for a family but there is also anecdotal evidence that after a career break, there is a tendency

for hygienists to lose some confidence in their abilities and experience difficulty in finding appropriate refresher courses. REFERENCES * Matthews R W, Scully C . Recent trends in

university entry for dentistry in the UK. _Br Dent J_ 1993; 175: 217–219. Article Google Scholar * Hillam D G . Career patterns of dental hygienists qualifying from the Liverpool Dental

Hospital School of Dental Hygiene. _Br Dent J_ 1989; 166: 310–311. Article Google Scholar * Matthews R W, Scully C . Working patterns of male and female dentists in the UK. _Br Dent J_

1994; 176: 463–466. Article Google Scholar * Bickley S R . _UK National Survey of Dental Hygienists 1994_ Brackley: Partners in Practice. April 1995. Google Scholar Download references

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Thanks are due to Stafford-Miller Ltd for financial assistance with the costs of this survey and also to the hygienists who responded to the questionnaire. Also, to the

staff of the Liverpool School of Dental Hygiene who have assisted in the development and maintenance of a corporate identity over many years, which has assisted in maintaining communication

with ex-students. AUTHOR INFORMATION AUTHORS AND AFFILIATIONS * Consultant in Restorative Dentistry, Director of School of Dental Hygiene, Liverpool University Dental Hospital, Pembroke

Place, Liverpool, L3 5PS D G Hillam Authors * D G Hillam View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar RIGHTS AND PERMISSIONS Reprints and permissions

ABOUT THIS ARTICLE CITE THIS ARTICLE Hillam, D. A survey of hygienists qualifying from the Liverpool School of Dental Hygiene 1977–1998. _Br Dent J_ 188, 150–153 (2000).

https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.4800417 Download citation * Published: 12 February 2000 * Issue Date: 12 February 2000 * DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.4800417 SHARE THIS ARTICLE Anyone

you share the following link with will be able to read this content: Get shareable link Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article. Copy to clipboard Provided by the

Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative