Identification of aba-responsive genes in rice shoots via cdna macroarray

- Select a language for the TTS:

- UK English Female

- UK English Male

- US English Female

- US English Male

- Australian Female

- Australian Male

- Language selected: (auto detect) - EN

Play all audios:

ABSTRACT Phytohormone abscisic acid (ABA) was critical for many plant growth and developmental processes including seed maturation, germination and response to environmental factors. With

the purpose to detect the possible ABA related signal transduction pathways, we tried to isolate ABA-regulated genes through cDNA macroarray technology using ABA-treated rice seedling as

materials (under treatment for 2, 4, 8 and 12 h). Of 6144 cDNA clones tested, 37 differential clones showing induction or suppression for at least one time, were isolated. Of them 30 and 7

were up- or down-regulated respectively. Sequence analyses revealed that the putative encoded proteins were involved in different possible processes, including transcription, metabolism and

resistance, photosynthesis, signal transduction, and seed maturation. 6 cDNA clones were found to encode proteins with unknown functions. Regulation by ABA of 7 selected clones relating to

signal transduction or metabolism was confirmed by reverse transcription PCR. In addition, some clones were further shown to be regulated by other plant growth regulators including auxin and

brassinosteroid, which, however, indicated the complicated interactions of plant hormones. Possible signal transduction pathways involved in ABA were discussed. SIMILAR CONTENT BEING VIEWED

BY OTHERS GENOME-WIDE IDENTIFICATION AND EXPRESSION ANALYSIS OF _CSABF/AREB_ GENE FAMILY IN CUCUMBER (_CUCUMIS SATIVUS_ L.) AND IN RESPONSE TO PHYTOHORMONAL AND ABIOTIC STRESSES Article

Open access 06 May 2025 GENOME-WIDE CHARACTERIZATION AND EXPRESSION ANALYSES OF THE _AUXIN/INDOLE-3-ACETIC ACID_ (_AUX/IAA_) GENE FAMILY IN BARLEY (_HORDEUM VULGARE_ L.) Article Open access

24 June 2020 GENOME-WIDE IN-SILICO ANALYSIS OF ETHYLENE BIOSYNTHESIS GENE FAMILY IN _MUSA ACUMINATA_ L. AND THEIR RESPONSE UNDER NUTRIENT STRESS Article Open access 04 January 2024

INTRODUCTION ABA (abscisic acid), an important growth regulator during plant growth and development, has been demonstrated to be involved in many plant developmental processes, especially

seed development including maturation and germination, and plant response to environmental factors. It has shown that ABA was accumulated rapidly during plant seed development or under the

stress condition of water deficiency, salt and cold conditions and further induced the expressions of the related genes to improve the resistance of plants1, 2, 3, or through the regulation

of PKABA, encoding a kind of protein kinase, and Gamyb to effect the ABA and GA antagonism during seed germination4. Studies by means of genetic and molecular technologies have resulted in

the identification of ABA-regulated genes and corresponding transcription factors necessary for ABA-related signal transduction (for review, see5, 6). Up to now, 6 genes, shown to be

necessary for the ABA-related signal transduction have been reported and their encoded proteins were classified as 2 transcription factors (VP1 of maize and ABI3 of Arabidopsis7, 8), 2

members of highly conserved protein phosphatase 2C family9, 10, 11, 1 transcription regulator harbouring APETALA 2 domain (ABI412) and 1 farnesyl transferase (ERA1 of Arabidopsis13). Studies

have been focused on the physiological roles of ABA and its related signal transduction5. However, the complication of ABA signal network made it relatively difficult to isolate and analyze

ABA-regulated genes with traditional methods14. Even until now, much was still unknown about the functional mechanism of ABA, especially the related signal transduction in plant cells. The

recently developed cDNA microarray technology enabled monitoring of cell-, tissue- and developmental stage-specific gene expression profiles and simultaneous quantitative analyses of

expression levels of genes15, 16, 17, 18, 19, which could help people to further find out new genes possibly involved in the same process or signaling pathway. This will help people to have

the general and full knowledges on certain developmental processes. cDNA microarray technology has also been used in plant research field for gene studies in recent years20. Schena et al.

first experimentally made the array with 45 Arabidopsis genes and successfully detected the difference of low expressed genes21. Through this technology, Reymond et al. analyzed 150 wounded

and insect-related genes of Arabidopsis22, and Grike et al. analyzed genes related to seed development of Arabidopsis and found 25% and 10% of the genes tested, in total 2600 arrayed genes,

increased 2 and 10 times respectively during Arabidopsis seed development23. Seki et al. analyzed expression patterns of 1300 Arabidopsis full-length cDNAs under cold and drought conditions,

and found 44 drought- and 19 cold-induced cDNAs, in which 30 and 12, respectively, were newly reported24. They also found 12 genes were induced by transcription factor DREB1A

(dehydration-response element binding protein) and further analyses showed that drought response elements were present in these 12 genes. All these results suggest that cDNA microarray would

be useful not only for isolation of new genes, which would certainly help people to study the general profiles of the tissue-specific or environment related cDNAs, but also for

identification of target genes and potential cis elements of transcription factors. We are interested in the ABA related signal transduction and its function mechanism in plants. Here we

report, based on the comparison of the differences of gene expression patterns through cDNA macroarray technology, the isolation and identification of ABA regulated genes in rice. We hope

this would possibly provide some hints for the mechanisms on ABA mediated signal transduction in plant cells. MATERIALS AND METHODS _MATERIALS_ ABA (abscisic acid) was obtained from Sigma

(USA). 96-well PCR plates were from ABGENE and 96-well cell plates were from Nunc. Taq polymerase and standard T3 and T7 primers were from Sangon (Shanghai, China). dNTP were obtained from

TaKaRa Biotechnology (Dalian, China). Radiochemical [α-33P]dCTP was obtained from ICN (Meckenheim, Germany). RNA reverse transcription labeling kit was obtained from GIBCO-BRL (USA). Primers

for reverse transcription PCR (RT-PCR) were obtained from TIB Molbiol (Berlin, Germany). _BACTERIA AND PLANT MATERIALS_ Escherichia coli JM109 cells were used for amplifying the cDNA

library. Cells were cultivated at 37°C in LB medium supplemented with appropriate antibiotics using standard methods25. Oryza sativa cv. Zhonghua 11 were germinated on 1/2 MS medium and

grown in water in phytotron with a 12 h light (26°C and 12-h dark (18 °C) period. _ABA TREATMENT AND RNA ISOLATION_ 2 week old rice seedlings (grown in water) were treated with 100 _μ_M ABA

for 2, 4, 8, 12 hrs and then frozen in liquid nitrogen for further analysis. Total RNA was prepared according to the extraction procedures of acid guanidinium thiocyanate-phenol-chloroform25

with few modifications: 1 g seedlings (including same amounts of treated materials for different time scales) were powdered in liquid nitrogen, extracted with guanidinium

thiocayanate-phenol-chloroform, then precipitated with ethanol and purified with LiCl and chloroform each time. Total RNA, suspended in RNase-free water finally, was stored at −70 after

spectrophotometrical quantification at 260 nm. _CDNA LIBRARY CONSTRUCTION AND MACROARRAY PREPARATION_ Collected ABA treated materials were used for plasmid cDNA library construction using

pBluescript vector by TaKaRa Biotechnology (Dalian, China). Titers of the cDNA library were calculated based on the white colonies obtained under the white/blue selection on the plate

supplemented with isopropylthio-β-D-galactoside (IPTG) and X-Gal after transferred to _E. coli_ cells via electroporation. A total of 6144 white colonies from the library were randomly

chosen from the plates (supplemented with appropriate concentration of ampicillin, X-Gal and IPTG) and cultured overnight in 96-well cell plates. cDNA insertions were then amplified with

standard T3 and T7 primers in 96-well PCR plate with T-gradient PCR instrument (Biometra Company, GÖtingen, Germany) using _E. coli_ culture as templates. PCR reactions were performed in a

total volume of 60 _μ_l (including 48 ml ddH2O, 6 ml 10×PCR buffer with 15 _μ_M MgSO4, 2.5 _μ_l 2.5 mM dNTP, 2 ml 20 pM primers, 0.5 _μ_l Taq polymerase and 1 _μ_l _E. coli_ culture as

template) as follows: 94°C for 3 min, 1 cycle; then with 40 cycles of 94°C for 1 min, 52°C for 1 min, 72°C for 3 min; and finally with an extension at 72°C for 10 min. PCR products were

checked on 1% agarose gel by electrophoresis. Nylon membranes (Hybond, Amersham) was precut and wetted with 2×SSC for DNA spotting. PCR products were arrayed on nylon membranes using Biomek

2000 HDRT system (Beckman, Fullerton, CA, USA) with the spotting procedures as follows: spotting needles stayed for 2 sec in DNA samples (in 96-well PCR plate) and 2 sec on nylon membranes,

then 5 sec in ddH2O twice for washing, 5 sec in 75% ethanol and dried for 10 sec. DNA samples were spotted in 4×4 array and each sample was duplicated on crossway which resulted in the 1536

DNA spots (16×96) standing for 768 cDNA clones on each membrane. After spotting membranes were then denatured (0.5 M NaOH, 1.5 M NaCl) for 1-5 min, neutralized (1.5 M NaCl, 0.5 M Tris.Cl, pH

7.4) for 5 min and washed with 2×SSC for 2-5 min, and then incubated at 80°C for 2 h for stabilization of DNA on the membranes. _HYBRIDIZATION AND IMAGE ANALYSES_ 5 mg rice total RNA,

extracted from ABA-treated (for 2 and 8 h) and untreated 2-week-old rice seedlings, respectively, was labeled with [α-33P]dCTP through reverse transcription using RNA labeling kit

(GIBCO-BRL, USA). Resulted products were quantified with liquid scintillation counting (Beckman LS6500, USA) and the labeled first strand cDNA with same amounts of radioactivities were used

as hybridization probes. Hybridization was performed at 65°C for more than 40 h in 250 m M sodium phosphate buffer pH7.2 containing 7% SDS, 1% BSA, and 1 m M EDTA. Washes were performed at

65°C in 2×SSC, 0.1% SDS for 15 min, 1×SSC, 0.1% SDS for 15 min and 0.2×SSC, 0.1% SDS for 20 min26. After overnight exposure, the images of membrane were scanned using phosphoimager

(FUJIFILM, Japan) and resulted profiles were analyzed with commercial image processing system AIS program (Imaging Research INC., USA). As each sample was spotted on the membrane with

duplication, signals acquired were calculated in the average of each clone for further comparison. After twice hybridizations using independent treated samples, differential expressed cDNA

clones with the ratio (treated/control) > 1.5 or < 0.5 were selected and sequenced for further analyses. _REVERSE TRANSCRIPTION PCR (RT-PCR) ANALYSIS_ RT-PCR analyses were carried out

to confirm the ABA regulation of selected clones revealed by cDNA macroarray. 5 mg total RNA, isolated form ABA-treated (for 0, 2, 4, 8 and 12 h) rice seedlings was reverse transcribted to

first strand cDNAs using oligo (dT) primer in a total volume of 40 μl according to supplier s instruction (SuperScript Pre-amplification System, Promega). Resulted cDNAs were then used as

templates for PCR amplification in a volume of 30 _μ_l as follows: 94°C for 3 min; then 30-35 cycles of 94°C for 40 sec, 56°C for 40 sec, 72°C for 45 sec; and finally with an extension at

72°C for 10 min. Primers used for the selected clones in RT-PCR were listed in the Tab 1. The rice Rac1 actin coding gene was used as positive internal control with primers RAc1-1 and 2 (Tab

1). Amplified PCR products (10 _μ_l) were electrophoresed on a 2.5% (w/v) agarose gel and monitored using the Gel Doc 2000 (Bio-Rad Company, USA). RESULTS _CDNA LIBRARY CONSTRUCTION AND

MACROARRAY PREPARATION_ Plasmid cDNA library using vector pBluescript was constructed with 100 _μ_M ABA-treated (for 2, 4, 8 and 12 h) rice seedlings and harboured a total of 3×105 white

colonies under white/blue selection. cDNA insertions were amplified via PCR using standard T3 and T7 primers and results showed that the sizes of insertions were between 0.5-3 kb, in 1.2 kb

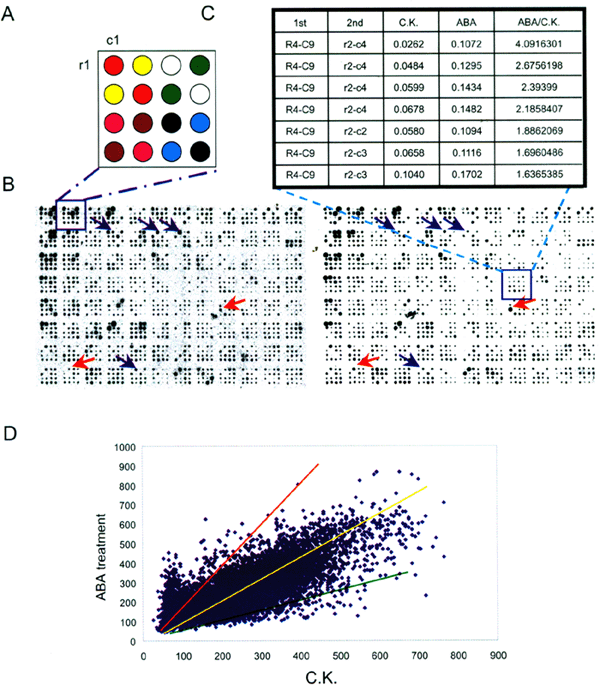

average. A total of 6144 PCR products representing same numbers of independent clones randomly chosen from plates were arrayed on 8 nylon membranes, on which there were 1536 DNA samples (in

a 4×4 array) spotted on each membrane for 768 cDNA clones with duplication on the crossway (Fig 1A) to ensure the results reproducible. _HYBRIDIZATION AND ISOLATION OF RICE ABA-REGULATED

GENES_ Rice total RNAs, extracted from ABA-treated (for 2, 4, 8 and 12 h) and untreated control materials (using liquid culture medium), were labeled with [α-33P]dCTP through reverse

transcription. Resulted labeled first strand cDNA were quantified with liquid scintillation counting and same amounts of labelled cDNAs were used as probes for hybridization. Resulted

images, as shown in Fig 1B, were then analyzed with AIS software through transferring the image signals to digital characteristics for detecting the differences between treated samples and

control (Fig 1C). As each clone was spotted on the membrane with duplication, digital characteristics acquired were analyzed with control in the average with ratio (treated/control) to test

the induction or suppression, i.e. <2.0 or <0.5 indicated the induction or suppression of the corresponding clones with one time level respectively. Hybridizations were repeated for

two times using independent treated samples. As shown in Fig 1D most of the samples (around 93% of the total clones) tested were located in a range between 2.0 and 0.5 that indicated no

response to ABA for most of the samples under 2-12 h ABA treatment. Thus, samples with the ratio > 1.5 (for detailed analysis with a extension from 2.0 to 1.5) or < 0.5 comparing to

control were picked out and original cDNA insertions were sequenced. In a total of 6144 arrayed cDNA clones, after sequencing, 41 were found to be regulated by ABA, in which 31 and 10 were

found to be up- and down-regulated respectively. Sequences of these 41 clones were then analyzed with BLAST program against database and 32 of them shared homologies with known proteins and

6 of them with unknown functions. The putative proteins encoded by identified clones were classified as different families involved in transcription (encoding bZIP, MADS, Myb transcription

factors), metabolism and resistance (encoding transferase, synthase and kinase), photosynthesis, signal transduction (encoding kinase, calmodulin and WD-repeat proteins), and seed

development. Results were shown in Tab 2. Among the identified clones, some cDNAs have been reported from rice, including phytoene synthase and putative bZIP (basic/leucine zipper)

transcription factors coding genes, have been demonstrated to be induced under stress situations 27 and cold stress28,29. Most of them were not reported before. _CONFIRMATION OF ABA

REGULATION WITH SELECTED CLONES_ Some clones, which encoded putative proteins involved in signal transduction, seed development or metabolism, were chosen for further RT-PCR analyses

(primers used were shown in Tab 1) to confirm the ABA regulation. To confirmed the materials used were in parallel and especially avoid of the affection of circadian regulation, control

plants (at exactly identical time scales with treatment) and treated rice seedlings were used for RNA extraction and further RT-PCR analysis. In total tested 7 clones, which encoded putative

ethylene-inducible protein (AJ437339), cold accumulation protein (Lip9) (AJ439990), sensory transduction histidine kinase (AJ437267), WD-repeat protein (AJ439992), glyoxalase I (AB017042),

calmodulin (AF231026) and sphingosine kinase (AJ437338), as shown in Fig 2, were detected to be regulated by ABA. The regulation tendencies of these clones fit the ratio results obtained

from macroarray. DISCUSSION _CDNA MACROARRAY AND HYBRIDIZATION_ cDNA microarray technology has been shown to be powerful to analyze expression profiles of numbers of genes in parallel so as

to find out new genes in specific tissue and organs or during specific growth and developmental stages, or under different conditions such as cold, salt stress, drought and pathogen

infection30, 31. One advantage of this technology was the possibility to find out the genes related to one process or developmental stage in one experiment in genome scale, this would

certainly provide informations for the complicated network of signal transduction32. However, the cost for microarray experiment performance is very expensive. Although the density of spots

in a certain space is less and quality of nylon will have more affection in the hybridization results than microarray, macroarray will be cheaper and convenient for general lab performance.

Since some steps may affect the macroarray results, including the array spotting, hybridization and evaluation of the results. To overcome the possible problems, we first spotted the DNA

samples into different membranes at same time to be sure the amounts of DNA with same samples spotted on different membranes are identical so that the comparison after hybridization was

believable, and spotted the same sample with duplication to confirm the results; second, quantified the hybridization probes after labeling with liquid scintillation counter to be sure the

radioactivities used during hybridization were identical to make the signals acquired comparative; and third, evaluated the image signals to digital characteristics to compare the

differences more precisely. In the experiments reported in this paper, 6144 cDNA clones, which possibly stand for the 10% or more cDNAs of rice were arrayed and tested, which provided the

possibility to isolate genes related to ABA signaling pathways from rice in genome scale. Amplification of cDNA insertions with standard primers made it relatively easier to perform the

amplification in large scales and the following spotting of PCR products. Hybridization of the arrayed nylon membranes using [33P]dCTP labeled first strand cDNAs (same amounts of

radioactivities of treated samples and control) was performed parallelly after reverse transcription and the following analyses with AIS program would be helpful for finding out the

differentially expressed clones. This was demonstrated, as shown in Fig 1d, that most of the clones tested within the range 0.5-2.0 in ratio. _ABA REGULATED GENES_ Genes selected from

macroarray, which provide hints for differential expressed gene isolation, still need further confirmation through either Northern blot or RT-PCR analysis. Sequence analyses and homologous

searches indicated that some clones, identified by cDNA macroarray, were indeed regulated by environmental factors, which suggested the possible relation to ABA and the involvement in

ABA-related signal transduction pathways. Protein encoded by clone Xd423 shared high homology (95%) to maize phytoene synthase, which was demonstrated to be induced under stress situations

(Steinbrenner and Linden, 2001). Protein encoded by clone Xd426 (X57325), a basic/leucine zipper transcription factor, was shown to be induced under cold treatment28,29. However,

confirmation of the identified clones is still required. RT-PCR results, however, 30% of clones (3 of 10) tested did not give PCR products, which might be due to the reason by PCR itself.

_POSSIBLE ABA RELATED SIGNALING PATHWAYS_ Most of the clones identified by cDNA macroarray were unknown or unreported to be related or involved in ABA mediated signal transduction before.

Based on RT-PCR confirmation for some clones related to different signal transduction pathways, we may suggest that some genes were involved in ABA mediated signaling pathways for stress

response. WD-repeat protein was demonstrated to be involved in many signal transduction pathways33, 34, 35 including SPA (inhibitor of PhyA36) and TRIP1 (subunit of eIF3, interacted with

TGF-β receptor, and may involve in the brassinosteroid stimulated plant growth37). A putative ABA induced WD-repeat protein, with 64% identities (80% homologies) to an Arabidopsis one4,33,

was indeed regulated by ABA. Histidine kinase plays a role in many signal transduction pathways38, 39, 40. Histidine kinase domain was found in phytochrome and related to rhymes41. The

recently reported CKI1, receptor of cytokinin in Arabidopsis, was a histidine kinase. Sphingosine kinase, together with phospholipase C, phospholipae D and MAPK, were involved in the cell

response to environmental stimuli including growth factors, cytokinin, G-protein coupled stimulator and so on40, 42, 43, 44. Up-regulation of rice histidine kinase and sphingosine kinase by

ABA treatment may suggest their roles in ABA function. Cold accumulation protein: ABA increased rapidly under cold stress and further induced related gene expression for plant resistance.

Cold-induced gene, Kin2, isolated from Arabidopsis, was induced by ABA, salt and drought45. A putative rice cold accumulation protein was isolated and confirmed to be induced by ABA

treatment, which shared 72% and 52% homologies with rice and wheat cold accumulation protein Lip9 and WCOR410b. Additionally, protein encoded by clone Xd481 (AJ439989) shared 68% homologies

to rice ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase (Rubisco), which catalyzed the reaction of oxygen and ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate resulting the production of glycerate-3-phosphate and

glycolic acid-2-phosphate. CO2 and NH3 were produced during the conversion of glycolic acid-2-phosphate to glycine. This reaction could prevent the overreduction of photosynthetic electron

transport chain in light respiration under stress situation so as to prevent the light inhibition. Furthermore, glycine, the metabolite of photorespiration, is the precursor of the synthesis

of glutathione, which also play a role in the responses of plant cells to environmental stress46. Induction of the expression of small chain precursor of Rubisco under ABA treatment may

suggest that under stress condition, increase of the Rubisco would stimulate the plant photorespiration, reduce the photoinhibition and result in the plant self protection. _INTERACTION OF

ABA WITH AUXIN AND BRS_ It should be noticed that the cross talk between different signaling pathways were widely present in plant cells, especially on hormone regulated pathways. We hereby

performed the analysis on the same samples under treatment with other hormones, i.e. auxin and brassinosteroid (Shen et al., submitted; Chu et al., submitted). Results of expression profiles

showed that some clones, regulated by ABA, were regulated by IAA or BR as well (Tab 3). The possible multi-regulated clones encoded putative cytochrome P450, MADS box transcription factor,

Proline-rich protein precursor, seed maturation protein and so on. Together with the results that ethylene-response protein was regulated by ABA (Fig 2, clone Xd439, AJ437339), although the

detailed analysis on the regulation by both hormones is still required, these may indicate the complicated interactions of signal pathways with different hormones. For example, polyubiquitin

expressed at variable amounts in many plant tissues with high levels in metabolically active and/or dividing cells, vascular tissues and was induced by wound, heat, or ethylene

treatments47, 48, 49. Although there was no report about the connection of auxin and ubiquitin, but the promoter of _GLP3b_ gene has a single putative auxin-response element, which was

physically linked to the polyubiquitin 4 gene50. In our experiments, we gave evidences that polyubiquitin played a role in both auxin and ABA functions. REFERENCES * Bray EA . Molecular

responses to water deficit. _Plant Physiol_ 1993; 103:1035–40. Article CAS Google Scholar * Jensen AB, Busk PK, Figueras M, Mar Alba, M, Perac-chia G, Messeguer R, Goday A, Pages M .

Drought signal transduction in plants. _Plant Growth Regulation_ 1996; 20:105–10. Article CAS Google Scholar * Machuka J, Bashiardes S, Ruben E, Spooner K, Cuming A, Knight C, Cove D .

Sequence analysis of expressed sequence tags from an ABA-treated eDNA library identifies stress response genes in the moss physcomitrella patens. _Plant Cell Physiol_ 1999; 40:378–87.

Article CAS Google Scholar * Gdmez-Cadenas A, Zentella R, Walker-Simmons MK, Ho, THD . Gibberellin/abscisic acid antagonism in barley aleurone cells: site of action of the protein kinase

PKABA1 in relation to gibberellin signaling molecules. _The Plant Cell_ 2001; 13:667–79. Article Google Scholar * Grill E, Himmelbach A . ABA signal transduction. _Curr Opin Plant Biol_

1998; 1:412–8. Article CAS Google Scholar * Shinozaki K, Yamaguehi-Shinozaki K . Molecular responses to dehydration and low temperature: differences and cross-talk between two stress

signaling pathways. _Curr Opin in Plant Bio_ 2000; 3:217–23. Article CAS Google Scholar * McCarty DR, Hattori T, Carson CB, Vasil V, Lazar M, Vasil I . The Viviparous-1 developmental gene

of maize encodes a novel transcriptional activator. _Cell_ 1991; 66:895–905. Article CAS Google Scholar * Giraudat J, Hauge B, Valon C, Smalle J, Parcy F, Goodman H . Isolation of the

Arabidopsis ABI3 gene by positional cloning. _The Plant Cell._ 1992; 4:1251–61. Article CAS Google Scholar * Leung 3, Bouvier-Durand M, Morris PC, Guerrier D, Chefdor F, Giraudat J .

Arabidopsis ABA response gene ABI1: Features of a calcium-modulated protein phosphatase. _Science_ 1994; 264:1448–52. Article CAS Google Scholar * Leung J, Merlot S and Giraudat J . The

Arabidopsis ABSCISIC ACID-INSENSITIVE2 (ABI2) and ABI1 genes encode homologous protein phosphatases 2C involved in abscisic acid signal transduction. _The Plant Cell_ 1997; 9:759–71. Article

CAS Google Scholar * Meyer K, Leube M and Grill E . A protein phosphatase 2C involved in ABA signal transduction in Arabidopsis thaliana. _Science_ 1994; 264:1452–5. Article CAS Google

Scholar * Finkelstein RR, Wang ML, Lynch T J, Rao S and Goodman HM . The Arabidopsis abscisic acid response locus ABI4 encodes an APETALA2 domain protein. _The Plant Cell_ 1998;

10:1043–54. CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Cutler S, Ghassemian M, Bonetta D, Cooney S and McCourt P . A protein farnesyl transferase involved in abscisic acid signal

transduction in Arabidopsis. _Science_ 1996; 273:1239–41. Article CAS Google Scholar * Genoud T, Metraux JP . Crosstalk in plant cell signaling: structure and function of the genetic

network. _Trends Plant Sci_ 1999; 4:503–7. Article CAS Google Scholar * Derisi J, Penland L, Brown PO, Bittner ML, Meltzer PS, Ray M, Chen Y, Su YA, Trent JM . Use of a cDNA microarray to

analyse gene expression patterns in human cancer. _Nature Genetics_ 1996; 14:457–60. Article CAS Google Scholar * Baldwin D, Crane V, Rice D . A comparison of gel-based, nylon filter and

microarray techniques to detect differential RNA expression in plants. _Curr Opin Plant Biol_ 1999; 2:96–103. Article CAS Google Scholar * van Hal NL, Vorst O, van Houwelingen AM, Kok E

J, Peijnenburg A, Aharoni A, van Tunen A J, Keijer J . The application of DNA microarrays in gene expression analysis. _J Biotech_ 2000; 78:271–80. Article CAS Google Scholar * Richmond

T, Somerville S . Chasing the dream: plant EST microarrays. _Curt Opin Plant Biol_ 2000; 3:108–16. Article CAS Google Scholar * Ye SQ, Lavoie T, Usher DC, Zhang LQ . Microarray, SAGE and

their applications to cardiovascular diseases. _Cell Res_ 2002; 12:105–15. Article Google Scholar * Wisman E, Ohlrogge J . Arabidopsis microarray service facilities. _Plant Physiol_ 2000;

124:1468–71. Article CAS Google Scholar * Schena M, Shalon D, Davis RW, Brown PO . Quantitative monitoring of gene expression patterns with a complementary DNA microarray. _Science._

1995; 270:467–70. Article CAS Google Scholar * Reymond P, Weber H, Damond M, Farmer EE . Differential gene expression in response to mechanical wounding and insect feeding in Arabidopsis.

_The Plant Cell_ 2000; 12:707–20. Article CAS Google Scholar * Girke T, Todd J, Ruuska S, White J, Benning C, Ohlrogge J . Microarray analysis of developing Arabidopsis seeds. _Plant

Physiol_ 2000; 124:1570–81. Article CAS Google Scholar * Seki M, Narusaka M, Abe H, Kasuga M, Yamaguchi-Shinozaki K, Carninci P, Hayashizaki Y, Shinozaki K . Monitoring the expression

pattern of 1300 Arabidopsis genes under drought and cold stresses by using a full-length cDNA microarray. _The Plant Cell_ 2001; 13:61–72. Article CAS Google Scholar * Sambrook J, Fritsch

EF, Maniatis T . Molecular Cloning: A laboratory Mannual, 2nd ed., Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY. 1989. * Fieuw S, Müler-Röber B, Galvez S, Willmitzer L .

Cloning and expression analysis of the cytosolic NADP+-dependent isocitrate dehydrogenase from potato: implications for nitrogen metabolism. _Plant Physiol_ 1995; 107:905–13. Article CAS

Google Scholar * Steinbrenner J, Linden H . Regulation of two carotenoid biosynthesis genes coding for phytoene synthase and carotenoid hydroxylase during stress-induced astaxanthin

formation in the green alga Haematococcus pluvialis. _Plant Physiol_ 2001; 125:810–7. Article CAS Google Scholar * Aguan K, Sugawara K, Suzuki N, Kusano T . Low-temperature-dependent

expression of a rice gene encoding a protein with a leucine-zipper motif. _Mol Gen Genet_ 1993; 240:1–8. Article CAS Google Scholar * Kim JC, Lee SH, Cheong YH, Yoo CM, Lee SI, Chun H J,

Hong JC, Lee SY, Lim CO, Cho MJ . A novel cold-inducible zinc finger protein from soybean, SCOF-1, enhances cold tolerance in transgenic plants. _Plant J_ 2001; 25:247–59. Article CAS

Google Scholar * Schenk PM, Kazan K, Wilson I, Anderson JP, Richmond T, Somerville SC, Manners JM . Coordinated plant defense responses in Arabidopsis revealed by microarray analysis. _Proc

Natl Acad Sci USA_ 2000; 97:11655–60. Article CAS Google Scholar * Wang R, Guegler K, LaBrie ST and Crawford NM . Genomic analysis of a nutrient response in Arabidopsis reveals diverse

expression patterns and novel metabolic and potential regulatory genes induced by nitrate. _The Plant Cell_ 2000; 12:1491–509. Article CAS Google Scholar * Arimura G, Tashiro K, Kuhara S,

Nishioka T, Ozawa R, Takabayashi J . Gene responses in bean leaves induced by herbivory and by herbivore-induced volatiles. _Biochem Biophys Res Commun_ 2000; 277:305–10. Article CAS

Google Scholar * Luo M, Costa S, Bernacchia G and Cella R . Cloning, characterization of a carrot cDNA coding for a WD repeat protein homologous to Drosophila fizzy, human p55CDC and yeast

CDC20 proteins. _Plant Mol Biol_ 1997; 34:325–30. Article CAS Google Scholar * de Vetten N, Quattrocchio F, Mol J, Koes R . The an11 locus controlling flower pigmentation in petunia

encodes a novel WD-repeat protein conserved in yeast, plants, and animals. _Genes & Dev_ 1997; 11:1422–34. Article CAS Google Scholar * Smith TF, Gaitatzes C, Saxena K, Neer EJ . The

WD repeat: a common architecture for diverse functions. _Trends Biochem Sci_ 1999; 24:181–5. Article CAS Google Scholar * Hoecker U, Tepperman JM, Quail PH . SPA1, a WD-repeat protein

specific to phytochrome A signal transduction. _Science_ 1999; 284:496–9. Article CAS Google Scholar * Jiang J, Clouse SD . Expression of a plant gene with sequence similarity to animal

TGF-beta receptor interacting protein is regulated by brassiuosteroids and required for normal plant development. _Plant J_ 2001; 26:35–45. Article CAS Google Scholar * Alex LA, Simon MI

. Protein histidine kinases and signal transduction in prokaryotes and eukaryotes. _Trends Genet_ 1994; 10:133–8. Article CAS Google Scholar * Lau PC, Wang Y, Patel A, Labbe D, Bergeron

H, Brousseau R, Konishi Y and Rawlings M . A bacterial basic region leucine zipper histidine kinase regulating toluene degradation. _Proc Natl Acad Sci USA._ 1997; 94:1453–8. Article CAS

Google Scholar * Meyer-zu-Heringdorf D, Lass H, Kuchar I, Lipinski M, Alemany R, Rumenapp U, Jakobs KH . Stimulation of intracellular sphingosine-l-phosphate production by G-protein-coupled

sphingosine-l-phosphate receptors. _Eur J Pharmacol_ 2001: 414:145–54. Article CAS Google Scholar * Grebe TW, Stock JB . The histidine protein kinase super-family. _Adv Microb Physiol_

1999; 41:139–227. Article CAS Google Scholar * Crowther GJ, Lynch DV . Characterization of sphinganine kinase activity in corn shoot microsomes. _Arch Biochem Biophys_ 1997; 337:284–90.

Article CAS Google Scholar * Nishiura H, Tamura K, Morimoto Y, Imai H . Characterization of sphingolipid long-chain base kinase in Arabidopsis thaliana. _Biochem Soc Trans_ 2000;

28:747–8. Article CAS Google Scholar * Pyne S, Pyne NJ . Sphingosine 1-phosphate signaling in mammalian cells. _Biochem J_ 2000; 349:385–402. Article CAS Google Scholar * Kurkela S,

Borg-Franck M . Structure and expression of kin2, one of two cold- and ABA-induced genes of Arabidopsis thaliana. _Plant Mol Biol_ 1992; 19:689–92. Article CAS Google Scholar * Wingler A,

Lea P J, Quick WP, Leegood RC . Photorespiration: metabolic pathways and their role in stress protection. _Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci_ 2000; 355:1517–29. Article CAS Google

Scholar * Finley D, Ozkaynak E, Varshavsky A . The yeast polyubiquitin gene is essential for resistance to high temperatures, starvation, and other stresses. _Cell_ 1987; 48:1035–46.

Article CAS Google Scholar * Garbarino JE, Rockhold DR, Belknap WR . Expression of stress-responsive ubiquitin genes in potato tubers. _Plant Mol Biol_ 1992; 20:235–44. Article CAS

Google Scholar * Takimoto I, Christensen AH, Quail PH, Uchimiya H, Toki S . Non-systemic expression of a stress-responsive maize polyubiquitin gene (Ubi-1) in transgenic rice plants. _Plant

Mol Biol_ 1994; 26:1007–12. Article CAS Google Scholar * Carter C, Graham RA, Thornburg RW . Arabidopsis thaliana contains a large family of germin-like proteins: characterization of

cDNA and genomic sequences encoding 12 unique family members. _Plant Mol Biol_ 1998; 38:929–43. Article CAS Google Scholar Download references ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Researches were supported

by “the State Key Project of Basic Research, G1999011604”, ”Key Project of Knowledge Innovation, CAS”, “the National Natural Science Foundation of China, No.30070073” and “National Sciences

Foundation of Pan-Deng”. We thank Prof. Bernd Müller-RÖber for helpful comments on the manuscript. Hybridization was performed in the Max-Planck-Institute of Molecular Plant Physiology

(Golm, Germany). We thank Prof. Bernd Müller-RÖber and Magdalena Ornatowska for help of the performance of hybridization. AUTHOR INFORMATION Author notes * Fang LIN and Shou Ling XU: These

authors contribute equally to the paper. AUTHORS AND AFFILIATIONS * National Laboratory of Plant Molecular Genetics, Institute of Plant Physiology and Ecology, Shanghai Institutes for

Biological Science (SIBS), Chinese Academy of Sciences, Fang LIN, Shou Ling XU, Wei Min NI, Zhao Qing CHU, Zhi Hong XU & Hong Wei XUE * Partner Group of Max-Planck-Institute of Molecular

Plant Physiology (MPI-MP) on Plant Molecular Physiology and Signal Transduction, 300 Fenglin Road, Shanghai, 200032, China Fang LIN, Shou Ling XU, Wei Min NI, Zhao Qing CHU, Zhi Hong XU

& Hong Wei XUE Authors * Fang LIN View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Shou Ling XU View author publications You can also search for

this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Wei Min NI View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Zhao Qing CHU View author publications You can also

search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Zhi Hong XU View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Hong Wei XUE View author publications You

can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar CORRESPONDING AUTHOR Correspondence to Hong Wei XUE. RIGHTS AND PERMISSIONS Reprints and permissions ABOUT THIS ARTICLE CITE THIS

ARTICLE LIN, F., XU, S., NI, W. _et al._ Identification of ABA-responsive genes in rice shoots via cDNA macroarray. _Cell Res_ 13, 59–68 (2003). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.cr.7290151

Download citation * Received: 26 July 2002 * Revised: 14 January 2003 * Accepted: 28 January 2003 * Issue Date: 01 February 2003 * DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.cr.7290151 SHARE THIS

ARTICLE Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content: Get shareable link Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article. Copy to clipboard

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative KEYWORDS * Oryza sativa * abscisic acid (ABA) * cDNA macroarray * responsive genes * signal transduction