Trends in clinical success rates and therapeutic focus

- Select a language for the TTS:

- UK English Female

- UK English Male

- US English Female

- US English Male

- Australian Female

- Australian Male

- Language selected: (auto detect) - EN

Play all audios:

Last year was a productive one for the pharmaceutical industry in terms of new drug approvals. A record 59 new drugs were approved by the FDA in 2018, while 42 new active substances were

recommended for authorization by the European Medicines Agency. Was this just a fleeting success or are there underlying trends to suggest that such performance can be sustained? Here, with

this question in mind, we present data from CMR International, which operates a consortium of innovative biopharmaceutical companies to measure and compare R&D performance on a

like-for-like basis. This consortium includes ~30 large, mid-sized and small companies, collectively representing ~80% of the top 20 biopharmaceutical companies by global R&D

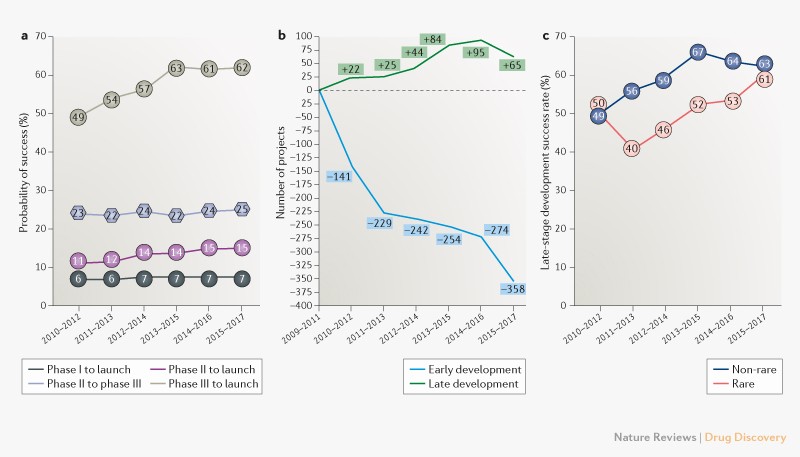

expenditure. We also analyse data on therapeutic area focus and on the originators of new drugs to further illuminate R&D trends. ANALYSIS Recent data from the CMR International

consortium indicate that success rates in late-stage development — from phase III through to launch — have increased from just under a one in two chance of getting to market at the beginning

of the decade to almost two in three in the most recent time period for which data are available, 2015–2017 (Fig. 1a). Meanwhile, phase II success rates have remained relatively static,

with only around a quarter of projects successfully progressing through phase II to phase III trials (Fig. 1a). While one can argue that there are cost benefits from failing in phase II

rather than phase III given the greater size and expense of late-stage clinical trials, the low phase II success rate reduces the current chance of a molecule making it to market from this

point to less than one in six (Fig. 1a). Finally, the probability of launch from entry to phase I has also stayed static at less than 10% (Fig. 1a). An analysis of the reasons for clinical

failure for the time period 2016–2018 indicates that these are largely unchanged over the previous 3-year time period (_Nat. Rev. Drug Discov._ 15, 817–818; 2016): 79% (versus 76%) were

attributable to safety or efficacy; 1% (versus 3%) were due to operational or technical shortcomings; 13% (versus 15%) were the result of strategic realignment; and 7% (versus 6%) were for

commercial reasons (_Drugs Today_ 53, 117–158: 2017; _Drugs Today_ 54, 137–167: 2018; _Drugs Today_ 55, 131–160: 2019). A popular model espoused in the early 2000s to counter attrition — the

‘shots on goal’ approach — was to push a greater number of projects into the pipeline. Data suggest that companies are now more selective about projects taken into early development, with a

sharp decline in early-stage project numbers over the decade (Fig. 1b). Some of this decline can be attributed to consolidation within the industry, particularly at the start of the decade

following the mega-mergers of Pfizer with Wyeth and Merck & Co. with Schering-Plough. However, it seems reasonable to conclude that companies are also making good on their public

aspirations to build ‘centres of excellence’ around their chosen franchises, with even the largest pharma companies sharpening their focus on particular therapeutic areas. Furthermore,

companies are typically employing various productivity strategies, such as AstraZeneca’s ‘5Rs’ to ensure that a drug candidate is acting as intended before advancing it into later-stage

clinical development (_Nat. Rev. Drug Discov._ 17, 167–181; 2018). The number of candidates in late-stage development has risen gradually until recently. However, the dip in 2015–2017 (Fig.

1b) could signal that the result of a more focused and strategic approach about progressing candidates in early-stage development is working its way through the pipeline, and that we will

now see the hoped-for outcome of a further boost in late-stage success rates. The choice of which therapy area to focus on can also affect success rates. Cardiovascular and nervous system

disorders are among those areas with the lowest probability of success over the 2010–2017 time period (Fig. 2), and could be a contributor to the deprioritization of such assets in several

companies’ pipelines. Another therapeutic area consideration with the potential to influence development success rates is the growth in the number of drugs for orphan indications or rare

diseases in company pipelines, a trend to which the increasing fragmentation of the oncology area has strongly contributed. Data from the CMR 2018 Global Clinical Performance Metrics Program

reveal that rare disease studies now account for nearly a quarter of all phase II and phase III trials combined. Improvement in the late-stage success rates for such molecules has lagged

those for non-rare diseases over the last decade, but the gap is narrowing (Fig. 1c). The concerted efforts of patient advocacy groups to raise disease awareness and develop patient

registries, as well as the introduction of additional regulatory support mechanisms, are likely factors behind this improvement. Since the introduction of the first orphan drug designation

programme in 1983 in the US, the number of new drugs approved for a rare disease has grown rapidly, and in 2018 a record 34 (58%) of the new drugs approved by the FDA had an orphan drug

designation. Notably, 27 of these 34 approvals were from smaller companies. The reduced scale of the clinical programmes and more specialized commercialization methods associated with rare

disease therapies have attracted investment from a slew of new biopharma companies, which may able to compete more effectively with larger companies in this field. Indeed, there has been an

overall decline in the number of new drugs brought through the US regulatory process by large pharma company sponsors in recent years (Fig. 3). A more detailed look at the originators of

these new drugs could provide more insight into whether we are truly seeing smaller companies take the lead in new drug development or whether they are engaged in large pharma partnerships

structured in such a way as to allow them greater responsibilities. It will also be interesting to observe what impact this change in the landscape of players will have on development

success rates in the future.