Label-free super-resolution imaging of adenoviruses by submerged microsphere optical nanoscopy

- Select a language for the TTS:

- UK English Female

- UK English Male

- US English Female

- US English Male

- Australian Female

- Australian Male

- Language selected: (auto detect) - EN

Play all audios:

ABSTRACT Because of the small sizes of most viruses (typically 5–150 nm), standard optical microscopes, which have an optical diffraction limit of 200 nm, are not generally suitable for

their direct observation. Electron microscopes usually require specimens to be placed under vacuum conditions, thus making them unsuitable for imaging live biological specimens in liquid

environments. Indirect optical imaging of viruses has been made possible by the use of fluorescence optical microscopy that relies on the stimulated emission of light from the fluorescing

specimens when they are excited with light of a specific wavelength, a process known as labeling or self-fluorescent emissions from certain organic materials. In this paper, we describe

direct white-light optical imaging of 75-nm adenoviruses by submerged microsphere optical nanoscopy (SMON) without the use of fluorescent labeling or staining. The mechanism involved in the

imaging is presented. Theoretical calculations of the imaging planes and the magnification factors have been verified by experimental results, with good agreement between theory and

experiment. SIMILAR CONTENT BEING VIEWED BY OTHERS HYPERBOLIC MATERIAL ENHANCED SCATTERING NANOSCOPY FOR LABEL-FREE SUPER-RESOLUTION IMAGING Article Open access 04 November 2022 CONFOCAL

INTERFEROMETRIC SCATTERING MICROSCOPY REVEALS 3D NANOSCOPIC STRUCTURE AND DYNAMICS IN LIVE CELLS Article Open access 07 April 2023 SINGLE-SHOT ISOTROPIC DIFFERENTIAL INTERFERENCE CONTRAST

MICROSCOPY Article Open access 12 April 2023 INTRODUCTION Optical microscopic imaging resolution has a theoretical limit of approximately 200 nm within the visible light spectrum due to the

far-field diffraction limit, which prevents the technique from being used for direct observation of live viruses (typically 5–150 nm, with some up to 300 nm). Progress in medical science and

treatment of disease would benefit significantly from the availability of an instrument that enables direct optical imaging with a high resolution beyond the optical diffraction limit.

Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) and scanning electron microscopy (SEM) are often used to image specially prepared dead virus structures at very high resolutions (<10 nm) in vacuum,

but they are unsuitable for the study of live viruses or virus/cell interactions. Fluorescence optical microscopy is a recently established method for the imaging of cellular structures,

bacteria and viruses beyond the optical diffraction limit, down to a resolution of 6 nm.1,2,3,4 This technique is based on the detection of light emitted by the fluorescing specimen when it

is excited by light of a specific wavelength. Structured illumination, such as stimulated emission depletion and saturated structured illumination microscopy, which activate florescent light

emission from a group of molecules simultaneously, are typically used.5,6 To enhance the imaging resolution, statistical reconstruction of the florescent light emission of single molecules

at different times, such as statistical optical reconstruction microscopy and photo-activated localization microscopy have been developed,7,8 whereby an optically blurred image is sharpened

through a deconvolution process, i.e., by digitally locating the peak of an optical profile or by using a point-spread function. The above fluorescent optical imaging techniques are

confronted with the challenge of photobleaching, which limits the maximum time of light exposure to tens of seconds.9 In addition, fluorescent optical imaging techniques often require the

conjugation of florescent molecules with the proteins of the target material, thus making such techniques somewhat intrusive, and only one type of stained protein can be imaged at a time,

whereas there are over 10 000 types of proteins in each cell. Scanning near-field optical microscopy, which is based on point-by-point scanning of a nano-scale optical tip very close (within

a few nanometers) to the target surface to illuminate the targets using the evanescent effect of the optical near-field, has demonstrated an imaging resolution of 60–100 nm.10 One of the

drawbacks of the scanning near-field optical microscopy technique is the long time required to acquire the full image, thus making it difficult to study the dynamic behavior of viruses and

cells. Imaging using a negative refractive index metamaterial has been shown to provide super-resolution capability down to 60 nm.11,12,13 The technique has, however, not yet been applied to

cell/virus imaging. The high level of light attenuation is one of the key barriers to the practical application of superlens techniques for super-resolution biomedical imaging. A recent

study using an X-ray femtosecond laser has shown super-resolution (subnanometer) imaging of virus particles just before their destruction.14 Super-oscillatory lens optical microscopy is

another recently reported subwavelength imaging technique, and is based on a binary nano-structured mask.15 The imaging resolution so far is 105 nm (_λ_/6), and it is suitable for imaging an

opaque target with transparent nano-structures. In 2011, a microsphere-coupled optical nanoscope was reported by some of the authors of this paper to have demonstrated an optical resolution

of 50 nm using a SiO2 microsphere (with a diameter of 2–5 µm) in air for the imaging of inorganic materials.16 Until now, there has been no report demonstrating white light direct optical

imaging of viruses below 100 nm in size. In this paper, we report the use of submerged microsphere optical nanoscopy (SMON) for the direct imaging of an adenovirus with a diameter of 75 nm

at a resolution beyond the optical diffraction limit. Large-diameter (100 µm) BaTiO3 spheres were used for this submerged optical imaging. The mechanisms involved in the dual-light

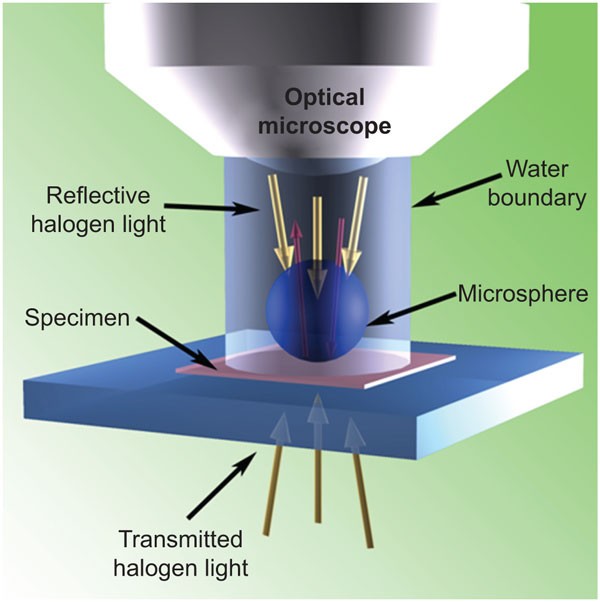

large-microsphere submerged optical imaging are described. MATERIALS AND METHODS IMAGING SET-UP Optically transparent microspheres of BaTiO3 with diameters of 100 µm (supplied by Cospheric

LLC; California, USA) were placed over the test specimen. Deionized water was deposited between the test specimen and the microscope lens. The optical microscope was used in both the

reflection and transmission modes (Figure 1). ADENOVIRUS SLIDE PREPARATION Replication-disabled adenoviruses of type 5 with deletions of the E1 and E3 genes were used. Adenovirus stock (109

MOI mL−1) was diluted 10 times in distilled H2O. For virus imaging using the BaTiO3 microsphere, the glass cover slide was first coated with a 5-nm-thick layer of gold to enable both optical

and SEM imaging. One microliter of diluted adenovirus stock was then spread onto the gold-coated microscope slide and air-dried. The viruses were then fixed with one drop of 4%

paraformaldehyde for 20 min, washed with tap water and then air-dried. TEM IMAGING SAMPLE PREPARATION For TEM imaging, diluted adenoviruses were loaded onto a carbon-coated TEM grid, which

was negative stained using uranyl acetate. RESULTS DEMONSTRATION OF SUPER-RESOLUTION IMAGING BY SMON To demonstrate the super-resolution capability of large-microsphere (100 µm) SMON and to

calibrate the imaging system, a Blu-Ray DVD disk with approximately 100-nm line spacing was imaged using an optical microscope (50×, NA=0.75) with a 100-µm diameter BaTiO3 microsphere in

water under white light (reflective mode) illumination. The imaging result is shown in Figure 2, along with an image obtained by SEM for comparison. The structure (100-nm spacing) observed

by the SMON technique is well beyond the spatial resolution limit of standard optical microscopes (approximately 200 nm). To further demonstrate the resolution of the SMON imaging using

large spheres submerged in water, an anodic aluminum oxide (AAO) sample was imaged with the 100-µm diameter BaTiO3 sphere coupled with a standard optical microscope submerged in water under

the transmission light-illumination mode. The average pore size of the AAO sample was approximately 50 nm, as shown in the SEM image (Figure 3a). This structure was captured by the SMON

imaging, as shown in Figure 3b, thus demonstrating the high-resolution imaging of the high refractive-index large-microsphere SMON approach with a 50-nm spatial resolution for images in

water. VIRUS IMAGING TEM imaging was first used to confirm the size of the replication-disabled viruses, as shown in Figure 4, which indicates the size of an individual adenovirus to be

approximately 75 nm. Virus imaging by SMON was performed using 100-µm diameter BaTiO3 fused glass microspheres (with a refractive index of _n_=1.9) coupled to an optical microscope. An

Olympus optical microscope with 80× and 100× objective lenses with NA=0.95 and NA=0.9 respectively in the reflection mode was used. The microsphere was placed on top of the viruses. Figure

5a (SEM image) shows the place of interested with a cluster of viruses. The yellow arrow points a C shaped mark which was used to help with aligning the microsphere with viruses. The red

arrow points to a shiny dust, which was helpful to find the right location of the viruses. Figure 5b confirms that a BaTiO3 microsphere was placed on top of viruses. This is a standard

microscope image with a 50× objective lens. The imaging plane was set on the specimen surface. By placing the microscopic imaging plane through the microsphere and into the specimen, a

clearer SMON image (Figure 5d) could be obtained with a focusing distance of 40 µm below the top surface of the specimen. The red arrow indicates the location of a shiny dust in the SEM

picture (Figure 5c). The viruses were, however, not seen with this optical set-up. A higher-magnification SMON image was obtained by using a 80× objective lens with NA=0.9. The individual

viruses were able to be resolved in Figure 5f. The imaging plane was set to 70 µm below the top surface of the specimen. Compared with the SEM image in Figure 5e, the SMON technique shows a

better resolution for this organic sample. Non-conductive substances would cause electron charges during the SEM imaging which would directly affect its resolution. Another higher

magnification SMON image (Figure 6a) was obtained by using a 100-µm BaTiO3 microsphere coupled with an optical microscope with a 100× objective lens with NA=0.95. Figure 6b provides the

quantitative intensity measurement from the reflective light emission. It clearly shows the peaks and separation between each spot. DISCUSSION SMON IMAGING MECHANISMS The Rayleigh criterion

for the diffraction limit of a standard optical microscope states is given by the following: where _d_min is the diffraction-limited optical resolution, _λ_ is the optical wavelength and

_NA_ is the numerical aperture of the microscope lens. For the optical microscopes used in this work, the theoretical diffraction limit resolutions of the light microscopes used in air for

white light illumination (wavelengths in the range of 390–700 nm) would be in the range 250–449 nm for the NA=0.95 objective lens. In water (refractive index=1.33), these theoretical

diffraction-limited imaging resolutions would be improved to 188–337 nm. Practical optical microscopes usually cannot reach the theoretical optical resolution due to spherical aberrations

and imperfections in the optics. By using the microspheres, we have demonstrated optical resolution in the range of 50–120 nm in water. This resolution is clearly beyond the optical

diffraction limits of these microscopes. To understand the super-resolution effect, three-dimensional electromagnetic (EM) numerical (time-domain finite difference) simulations were

performed using Computer Simulation Technology Microwave Studio software for two different sphere materials (BaTiO3 and polystyrene) and compared with the experimental data. An ideal

diffraction limit model was developed, in which two 100-nm slits with a 50-nm pitch are embedded in a 20-nm thick perfect electric conductor in water. The materials of the microspheres used

in the simulation are polystyrene (PS), with a refractive index of 1.59 (used in Figure 7a, 7b and 7d) and BaTiO3, with a refractive index of 1.9 (used in Figure 7e). The diameter of all the

spheres is 10 µm. The substrate thickness is assumed to be 20 nm. The light wavelength is set to the center of the visible spectrum, i.e., 550 nm. The ambient condition in the model is

water (refractive index _n_=1.33). When an EM plane wave (wavelength of 550 nm) arrives on the substrate, most of light energy is reflected, and only a small fraction is able to pass through

the nano-slits (Figure 7a). The penetrated energy decays very rapidly and thus cannot be captured by a far-field detector. Based on the theory of Wolf and Nieto-Vesperinas,17 evanescent

waves exist near the slits, and the fine structure information is encoded within this near field region. When a PS microsphere is placed beneath the nano-slits in the water environment, a

weak energy coupling caused by the conversion of the evanescent waves to propagating waves occurs, as shown in Figure 7b. This coupling occurs through the mechanism of frustrated total

internal reflection.18,19 The converted propagating waves contain the high spatial-frequency information of the sub-wavelength slits.20 However, the converted propagating waves do not

transmit beyond the sphere. This lack of transmission occurs when the imaging sample is under transmitted light-illumination mode. The super-resolution strength is mainly dependent on a

narrow window of (_n_,_q_) parameters, where _n_ is the refractive index of microsphere and _q_ is the size parameter, defined as _q_=2_πa_/_λ_ according to Mie theory.21 Figure 7c

illustrates the light rays passing through the microsphere under the transmission imaging mode. When the transmitted light first passes into the microsphere, the light is focused as

indicated by the black arrow lines. Some of the focused light is reflected at the interface of the top half of the sphere surface (as shown by the red arrow lines) and is refocused by the

microsphere. During this process, the photonic nano-jets (i.e., a higher-intensity optical field located below the sphere that has a higher density spot beyond the optical diffraction limit)

are generated, similar to the case in the reflection mode.16 The nano-jets arrive on the sample surface and illuminate the area below the microsphere at a high intensity and a high

resolution, beyond the diffraction limit. This nano-jet super-resolution focusing phenomenon has been applied for laser nano-fabrication.22,23,24 By reversing this optical path,

super-resolution imaging can be realized. The microsphere re-collects the light scattered by the virus/cells and converts the high spatial-frequency evanescent waves (no diffraction limits)

into propagating waves that can be collected by far-field imaging. To illustrate this effect, a three-microsphere model is developed, as shown in Figure 7d, to decouple the projected and the

received light through pure evanescent wave conversion. The top sphere is used to simulate the first pass of the light beam into the microsphere, i.e., the black arrow lines indicating the

light rays, as shown in Figure 7c. The refocusing process of the reflected light from the top semi-sphere surface (i.e., the red arrow lines indicated in Figure 7c) or the reflected light

projection from the optical microscope is simulated by the middle microsphere, as shown in Figure 7d. Photonic nano-jets are generated and redirected onto the substrate surface that is in

contact with the bottom of the middle microsphere. The microsphere converts the evanescent waves from the target surface into propagating waves. To clearly demonstrate this conversion

process, a conjugate model was developed (Figure 7d) to decouple the scattered light from the incident light waves. The space beneath the substrate can be considered to be the conjugate

‘virtual’ space. The conjugate space has the same ‘structure’ as the real space shown in Figure 7c and is symmetric to the substrate surface. Therefore, the lowest microsphere in Figure 7d

represents the conjugate space structure. The EM field in the conjugate space can be considered to be the collected EM field in the real space from the substrate surface without the

background of the incident light waves. The substrate with two 100-nm slits and a 50-nm pitch is used as the fine structure. Based on this simulation set-up, the energy coupling from the

evanescent waves into propagating waves can be clearly displayed in the transmission imaging mode or by using the reflection and dual reflection and transmission mode. The above simulations

indicate that the microsphere significantly enhances the energy penetration through subdiffraction-limit slits. This enhanced transmission can be attributed to the fact that the microspheres

in the conjugate space (beneath the substrate) and in the real space (above the substrate) are close to each other. Hence, a phenomenon known as frustrated total internal reflection occurs,

and the evanescent waves containing the high spatial-frequency information of the slits are linearly converted into propagating waves.18 Meanwhile, the photonic nano-jets generated by the

two microspheres in the real space further enhance the energy coupling into the conjugate space; thus, the converted propagating waves have sufficient energy away from the microsphere for

far-field imaging (as shown in Figure 7d). Therefore, the microsphere plays a dual-role for nano-imaging under both the transmission and reflection microscope imaging modes: (i) to generate

photonic nano-jets by the top sphere for super-resolution target illumination and (ii) to convert the high spatial-frequency evanescent waves into magnified propagating waves for far-field

detection. To further understand the mechanism of subdiffraction-limit imaging _via_ BaTiO3 microspheres in water in the reflection microscope imaging mode, a numerical simulation is

performed using the three-dimensional finite-difference time-domain method for a 10-µm diameter BaTiO3 sphere submerged in water, as shown in Figure 7e. Considering the reflection

configuration used in the imaging, the incident light first passes through the sphere and is focused by the microsphere. During this process, the sphere generates ‘photonic nano-jets’ with

super-resolution.19,21,22,23 When the focused incident light illuminates the target surface, the reflected light can be recollected by the microsphere in the near-field. Using the conjugate

model, the incident and reflected light waves are decoupled. As shown in Figure 7e, the upper half of the model is in real space, which describes the behavior of the light wave incident onto

the target surface _via_ the microsphere, whereas the lower half is the conjugate space, of which the ‘structure’ is same as real space and symmetric to the substrate surface. The conjugate

space is used to show the reflected light wave without the background of the incident light waves. The microsphere transmits the energy coupled from the real space to the conjugate space

through the subdiffraction-limit slits. The evanescent waves that contain the high spatial-frequency information (i.e., fine structures) are converted into propagating waves. The

nano-photonic jets generated _via_ the upper microsphere provide enough energy coupling to enable far-field imaging. Hence, subdiffraction-limit nano-imaging can be achieved using BaTiO3

microspheres in water for reflection mode microscopy. The simulation indicates that super-resolution imaging is possible in water with the aid of microspheres in both transmission and

reflection modes. The super-resolution virus imaging is obviously attributed to the existence of the transparent microspheres. We compare the SMON with super-solid immersion lens imaging to

identify the differences. Based on the solid immersion lens theory, the maximum imaging resolution improvement by a microsphere should be _n_0/_n_1.25 The maximum imaging resolutions

achieved using a solid immersion lens are 163 nm and 137 nm for the PS and BaTiO3 microspheres in water, respectively, for the microscope used in this study. Based on the super solid

immersion lens effect, the magnification _via_ the microsphere can be calculated as (_n_1/_n_0)2. For the PS microspheres (_n_1=1.60) in water (_n_1=1.33), the magnification should be 1.45.

For the BaTiO3 microspheres (_n_1=1.9) in water, the magnification is approximately 2.0. The experimental values of the image magnifications in water by the microspheres are higher (1.5–3

for the PS spheres and 2.5–4 for the BaTiO3 spheres) than those by the solid immersion lens effect. The experimental imaging resolution is also higher than the theoretical limit of the solid

immersion lens. Therefore, the microsphere plays an important role in transforming the high-resolution evanescent waves in the near field into far-field propagating waves. Because there is

no diffraction limit for evanescent waves, the only limitation is the means of transforming the near-field evanescent waves into far-field propagating waves with sufficient image

magnification so that it falls within the optical resolution of the standard optical microscope used to collect the image. Therefore, image magnification is very important. In addition, the

SMON imaging plane was found to not be on the target surface but well below it; i.e., the images are virtual.16 The imaging plane position and additional image magnification factor

introduced by the microsphere can be determined by considering the spherical lens effect and spherical aberration, as follows: where _f_ is the focal length of the microsphere from the

sphere center, _d_ is the transverse distance from the optical axis, _R_ is the microsphere radius, _n_0 is the ambient refractive index, _n_1 is the refractive index of the microsphere, _s_

is the virtual imaging plane position from the center of the microsphere, _M_ is the microsphere image magnification factor and _δ_ is the distance from the target to the microsphere

surface. Table 1 lists the range of the paraxial focal length of various microspheres in air and water, where the virtual imaging plane position range caused by the spherical aberration was

also considered. All the imaging planes are below the microsphere, and the microspheres in water have closer imaging planes to the sphere. The short imaging plane range could be beneficial

to obtaining a clearer nano-image without significant spherical aberration blurring. Note that the paraxial imaging plane generated by the BaTiO3 microspheres is far away from the target

surface in air and hence it cannot be captured by the objective lens used in this work. When the BaTiO3 was submerged into water, the paraxial imagine plane is located closer to the

microsphere, with a distance that the objective lens can image. Figure 8 illustrates the paraxial focal length, determined by Equation (2), and the imaging plane position, determined by

Equaton (3). Applying Equations (3) and (4), the magnification factors and the virtual imaging plane positions for the various microspheres used in this work can be determined. Tables 2 and

3 list the calculated results in comparison with the experimental values, where the effect of _δ_ was considered in the magnification factor calculations. The theoretical results exhibit

good agreement with the experimental results. ENGINEERING AND PRACTICAL ASPECTS OF SMON IMAGING OF BIOMEDICAL SPECIMENS Because the microspheres have a curved surface close to the target,

the distance between the microsphere and the target differs at different locations away from the center. It is important to know whether evanescent waves still exist towards the edges, where

the distance from the sphere surface to the target surface is large. For example, when a 50-µm diameter microsphere is placed on a flat surface, the distance, _x_, separating the

microsphere surface from the sample surface is increased to up to 700 nm when the lateral position is 6 µm from the central axis, as shown in Figure 9. Considering the evanescent wave decay

from the object surface, the wave vector _k__z_ of evanescent waves can be expressed as follows: Substituting the evanescent form of the wave vector _k_, the transmitted wave can be written

as follows: When the electric field _E_≥_E_0/_e_, the evanescent wave energy can be coupled into the microsphere and converted into propagating waves. Therefore, the following equation must

be satisfied to identify the maximum plane wave vector () that can be collected by microspheres: where _d_ is the distance between the object surface and the microsphere surface. From

Equation (7), even if there is a distance between the object and the microsphere, some of the evanescent waves that contain high spatial-frequencies beyond diffraction limit can still be

collected by the microsphere. However, the subdiffraction-limit frequencies that can be collected by the microsphere are dramatically reduced as the distance _d_ increases. For example, when

the distance is the light wavelength, the maximum plane wave vector () is 1.01_nω_/_c_, i.e., the maximum resolution is improved by approximately 1.01 times. Therefore, the distance between

object and microsphere surfaces should be on the same order as the light wavelength to obtain a significant imaging resolution improvement. In our experiment, the distance at a position 6

µm away from the 50-µm sphere center is calculated to be ∼700 nm, which is within the optical wavelength range of 400–700 nm. The SMON super-resolution can therefore be achieved for an

imaged area within a radius of 6 µm. The use of a gold coating on the glass substrate was found to increase the imaging magnification and sharpness when a nano-structure existed, as in the

AAO sample, because the surface plasmonic effect can enhance the evanescent waves. The placement of the microsphere on the target surface ensures consistency in the distance between the

sphere and the target. This is, however, not necessarily the optimum condition. In practical applications of the SMON, the microsphere needs to be attached to the optical microscope

objective lens with a specific distance between the sphere and the objective lens, depending on the lens optical properties (e.g., focal length and numerical aperture) and the imaging media

(water, oil or biological liquid). This distance also allows a small distance to be created between the sphere and the target distance (<1× optical wavelength) so that the target can move

freely below the sphere. This paper demonstrates the principles and feasibility of the super-resolution imaging of biological samples. Further work is required to create a practical imaging

device based on the SMON principle with the optimized microspheres attached to the microscope objective lens. The microsphere diameter needs to be chosen carefully. As listed in Table 1,

the paraxial imaging plane position depends on the microsphere diameter. A large microsphere can form the paraxial-imaging plane slightly away from the target surface. The resulting small

separation of the imaging plane from the target surface reduces the blurring effect caused by the scattered light from the target surface. The presence of liquid (especially the immersion of

the objective lens) is important to allow effective coupling of the optical images from the microsphere to the optical microscope. For a BaTiO3 microsphere, no images could be obtained in

air because the first virtual imaging plane was far away from the target surface (approximately 18_R_). Water can reduce the distance between the imaging plane and the surface; however, the

imaging magnification factor is reduced compared with the dry condition due to the increased refractive index of the medium. For biomedical imaging, there are several techniques available,

primarily dominated by the use of fluorescent light optical microscopy, to achieve super-resolution. However, fluorescent light optical microscopy only images certain parts of the protein

that emit fluorescent light. Holographic imaging is another technique that has been reported to be able to image biological materials, such as bacteria.24,26 Holographic imaging does not

directly observe objects. Instead, it relies on the detection and digital processing of diffraction patterns when the object is illuminated. Based on the differences of the surface texture,

analysis of the detected holograms provides information on the identities of different cell types. Therefore, the current application of holographic imaging in cell biology has been limited

to cell sorting and identification, i.e., cytometry systems. Holographic imaging is able to distinguish bacteria from red blood cells in whole blood samples, which could be used for the

diagnosis of infectious diseases.26 However, holographic imaging has not been able to acquire super-resolution images of cellular structures without being combined with an electron

microscope or an atomic force microscope. Digital or computational holography has the advantage of acquiring high-contrast three-dimensional pictures of un-labeled cells.27 The use of

two-dimensional evanescent standing wave illumination has been shown by Chung _et al._27 to improve the image resolution of a standard total internal reflection fluorescent optical

microscope to approximately 100 nm for cell imaging. A continuous-wave 532-nm laser was used for the illumination. Standard total internal reflection fluorescent microscopy has been

demonstrated to be able to image sindbis virus and HIV virus. Total internal reflection fluorescent microscopy requires fluorescent staining. The use of white light illumination in the SMON

imaging method enables the use of standard low-cost optical microscopes for super-resolution imaging if used in conjunction with suitable microspheres and the imaging procedures reported in

this paper. CONCLUSIONS A simple method for direct white-light optical observation of 75-nm adenoviruses was demonstrated for the first time by coupling a standard optical microscope with a

100-µm diameter BaTiO3 microsphere in water without fluorescent particle labeling. The mechanism of super-resolution imaging using SMON was found to be based on the conversion of evanescent

waves in the near field into the magnified prorogating waves in the far field by the microsphere through the mechanism of frustrated total internal reflection. Nano-jet formation through

focusing of light by the microsphere plays an important role in enhancing the image contrast by delivering the converted propagating wave to the space outside the sphere. Because evanescent

waves do not have a diffraction limit, the transformation of the evanescent wave to a magnified propagating wave within the optical resolution limit of a standard optical microscope is

important. In other words, the resolution of the microsphere-based optical imaging, although theoretically unlimited, is limited in practice by the magnification factor of the microsphere in

converting the evanescent wave to the propagating wave. Qualitative relationships to determine the imaging plane location (normally well below the microspheres) and the microsphere-induced

magnification factors for the SMON were derived and compared to the experiments, with close agreement. This work opens new opportunities for the study of virus/cell/bacteria/drug

interactions to better understand the causes of various deceases; super-resolution direct optical SMON imaging has the potential to become an alternative and complimentary technique to

fluorescent optical microscopy and electron microscopy. AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS LL conceived the concept, led the research, participated in the virus imaging experiments and prepared the

manuscript. TW prepared all the biological imaging samples, performed the TEM imaging of the viruses, participated in the optical imaging experiments and contributed to the manuscript

preparation. WG performed the virus imaging experiment and contributed to the manuscript writing. YY performed the theoretical simulation work and contributed to the manuscript preparation,

particularly on the Discussion section. SL performed the Blu-Ray and AAO imaging experiments, participated in the SMON biological sample imaging experiments and contributed to the manuscript

preparation. REFERENCES * Hell SW . Far-field optical nanoscopy. _Science_ 2007; 316: 1153–1158. Article ADS Google Scholar * Huang B, Wang W, Bates M, Zhuang X . Three-dimensional

super-resolution imaging by stochastic optical reconstruction microscopy. _Science_ 2008; 319: 810–813. Article ADS Google Scholar * Stone MD, Mihalusova M, O'Connor CM, Prathapam R,

Collins K _et al_. Stepwise protein-mediated RNA folding directs assembly of telomerase ribonucleoprotein. _Nature_ 2007; 446: 458–461. Article ADS Google Scholar * Huang B, Babcock H,

Zhuang X . Breaking the diffraction barrier: super-resolution imaging of cells. _Cell_ 2010; 143: 1047–1058. Article Google Scholar * Hell SW, Wichmann J . Breaking the diffraction

resolution limit by stimulated emission: stimulated-emission-depletion fluorescence microscopy. _Opt Lett_ 1994; 19: 780–782. Article ADS Google Scholar * Heintzmann R, Jovin TM, Cremer C

. Saturated patterned excitation microscopy—a concept for optical resolution improvement. _J Opt Soc Am A Opt Image Sci Vis_ 2002; 19: 1599–1609. Article ADS Google Scholar * Rust MJ,

Bates M, Zhuang X . Sub-diffraction-limit imaging by stochastic optical reconstruction microscopy (STORM). _Nat Methods_ 2006; 3: 793–795. Article Google Scholar * Betzig E, Patterson GH,

Sougrat R, Lindwasser OW, Olenych S _et al_. Imaging intracellular fluorescent proteins at nanometer resolution. _Science_ 2006; 313: 1642–1645. Article ADS Google Scholar * Renn A,

Seelig J, Sandoghdar V . Oxygen-dependent photochemistry of fluorescent dyes studied at the single molecule level. _Mol Phys_ 2006; 104: 409–414. Article ADS Google Scholar * Dürig U,

Pohl DW, Rohner F . Near-field optical-scanning microscopy. _J Appl Phys_ 1986; 59: 3318–3327. Article ADS Google Scholar * Pendry JB . Negative refraction makes a perfect lens. _Phys Rev

Lett_ 2000; 85: 3966–3969. Article ADS Google Scholar * Fang N, Lee H, Sun C, Zhang X . Sub-diffraction-limited optical imaging with a silver superlens. _Science_ 2005; 308: 534–537.

Article ADS Google Scholar * Smolyaninov II, Davis CC, Elliott J, Wurtz GA, Zayats AV . Super-resolution optical microscopy based on photonic crystal materials. _Phys Rev B_ 2005; 72:

085442. Article ADS Google Scholar * Chapman HN, Fromme P, Barty A, White TA, Kirian RA _et al_. Femtosecond X-ray protein nanocrystallography. _Nature_ 2011; 470: 73–78. Article ADS

Google Scholar * Roger ET, Lindberg J, Roy T, Savo S, Chad JE _et al_. A super-oscillatory lens optical microscope for subwavelength imaging. _Nat Mater_ 2012; 11: 432–435. Article ADS

Google Scholar * Wang Z, Guo W, Li L, Luk'yanchuk B, Khan A _et al_. Optical virtual imaging at 50 nm lateral resolution with a white-light nanoscope. _Nat Commun_ 2011; 2: 218.

Article Google Scholar * Richards B, Wolf E . Electromagnetic diffraction in optical systems. II. Structure of the image field in an aplanatic system. _Proc R Soc Lond A_ 1959; 253:

358–379. Article ADS Google Scholar * Courjon D, Bainier C . Near field microscopy and near field optics. _Rep Prog Phys_ 1994; 57: 989–1028. Article ADS Google Scholar * Li L, Guo W,

Wang ZB, Liu Z, Whitehead D _et al_. Large area laser nano-texturing with user-defined patterns. _J Micromech Microeng_ 2009; 19: 064002. Google Scholar * Webb RH . Confocal optical

microscopy. _Rep Prog Phys_ 1996; 59: 427–471. Article ADS Google Scholar * Wang Z, Joseph N, Li L, Luk'yanchuk BS . A review of optical near-fields in particle/tip-assisted laser

nanofabrication. _Proc IMechE Part C_ 2010; 224: 1113–1127. Article Google Scholar * Guo W, Wang ZB, Li L, Liu Z, Luk'yanchuk B . Chemical-assisted laser parallel nanostructuring of

silicon in optical near fields. _Nanotechnology_ 2008; 19: 455302. Article Google Scholar * Li L, Hong M, Schmidt M, Zhong M, Mashe M _et al_. Laser nano-manufacturing—state of the art and

challenges (Keynote at 61st CIRP General Assembly, 21–27 August Budapest 2011). _CIRP Ann_ 2011; 60: 735–755. Article Google Scholar * Seo S, Su TW, Tseng D, Erlinger A, Izcan A .

Lens-free holographic imaging for on-chip cytometry and dianostics. _Lab Chip_ 2009; 9: 777–787. Article Google Scholar * Serrels KA, Ramsay E, Dalgarno PA, Gerardot BD, O'Connor JA

_et al_. Solid immersion lens applications for nanophotonic devices. _J Nanophoton_ 2008; 2: 021854. Article Google Scholar * Moon I, Daneshpanah M, Anand A, Javidi B . Cell identification

with computational 3D holographic microscopy. _Opt Photon News_ 2011; 22: 18–23. Article Google Scholar * Chung E, Kim D, Cui Y, Kim YH, So PT . Two-dimensional standing wave total

internal reflection fluorescence microscopy: superresolution imaging of single molecular and biological specimens. _Biophys J_ 2007; 93: 1747–1757. Article Google Scholar Download

references ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS We thank Dr Peter March for his help in using microscopes in the Bio-imaging Facility, Dr Aleksandr Mironov for his help with the electron microscope Facility in

the Faculty of Life Sciences, the University of Manchester, and Dr Zengbo Wang for technical discussions during the early stages of the work. AUTHOR INFORMATION AUTHORS AND AFFILIATIONS *

Laser Processing Research Centre, School of Mechanical, Aerospace and Civil Engineering, and Photon Science Institute, The University of Manchester, Manchester M13 9PL, UK Lin Li, Wei Guo,

Yinzhou Yan & Seoungjun Lee * Faculty of Medical and Human Sciences, The University of Manchester, Manchester M13 9PL, UK Tao Wang Authors * Lin Li View author publications You can also

search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Wei Guo View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Yinzhou Yan View author publications You can

also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Seoungjun Lee View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Tao Wang View author publications

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar CORRESPONDING AUTHOR Correspondence to Lin Li. RIGHTS AND PERMISSIONS This work is licensed under the Creative Commons

Attribution-NonCommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 Unported License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/ Reprints and permissions ABOUT

THIS ARTICLE CITE THIS ARTICLE Li, L., Guo, W., Yan, Y. _et al._ Label-free super-resolution imaging of adenoviruses by submerged microsphere optical nanoscopy. _Light Sci Appl_ 2, e104

(2013). https://doi.org/10.1038/lsa.2013.60 Download citation * Received: 29 August 2012 * Revised: 24 June 2013 * Accepted: 25 June 2013 * Published: 27 September 2013 * Issue Date:

September 2013 * DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/lsa.2013.60 SHARE THIS ARTICLE Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content: Get shareable link Sorry, a shareable

link is not currently available for this article. Copy to clipboard Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative KEYWORDS * imaging * microscope * optical *

super-resolution * virus