Tuning the chemiluminescence of a luminol flow using plasmonic nanoparticles

- Select a language for the TTS:

- UK English Female

- UK English Male

- US English Female

- US English Male

- Australian Female

- Australian Male

- Language selected: (auto detect) - EN

Play all audios:

ABSTRACT We have discovered a strong increase in the intensity of the chemiluminescence of a luminol flow and a dramatic modification of its spectral shape in the presence of metallic

nanoparticles. We observed that pumping gold and silver nanoparticles into a microfluidic device fabricated in polydimethylsiloxane prolongs the glow time of luminol. We have demonstrated

that the intensity of chemiluminescence in the presence of nanospheres depends on the position along the microfluidic serpentine channel. We show that the enhancement factors can be

controlled by the nanoparticle size and material. Spectrally, the emission peak of luminol overlaps with the absorption band of the nanospheres, which maximizes the effect of confined

plasmons on the optical density of states in the vicinity of the luminol emission peak. These observations, interpreted in terms of the Purcell effect mediated by nano-plasmons, form an

essential step toward the development of microfluidic chips with gain media. Practical implementation of the discovered effect will include improving the detection limits of

chemiluminescence for forensic science, research in biology and chemistry, and a number of commercial applications. SIMILAR CONTENT BEING VIEWED BY OTHERS OPTOFLUIDIC TRANSPORT AND ASSEMBLY

OF NANOPARTICLES USING AN ALL-DIELECTRIC QUASI-BIC METASURFACE Article Open access 28 July 2023 MEASURING NANOPARTICLES IN LIQUID WITH ATTOGRAM RESOLUTION USING A MICROFABRICATED GLASS

SUSPENDED MICROCHANNEL RESONATOR Article Open access 30 August 2022 LOSSLESS ENRICHMENT OF TRACE ANALYTES IN LEVITATING DROPLETS FOR MULTIPHASE AND MULTIPLEX DETECTION Article Open access 17

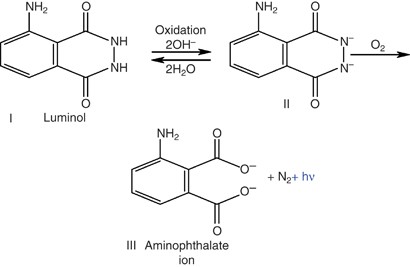

December 2022 INTRODUCTION Chemiluminescence is a fascinating optical effect that is used in various applications, from forensic science to industrial biochemistry. Luminol is a chemical

that exhibits chemiluminescence (Figure 1), emitting a blue glow. Approximately five decades ago, luminol was used for the first time to analyze a crime scene in Germany1. Since then, it has

become a very popular criminology tool, as it can reveal blood stains. A mixture of luminol, hydrogen peroxide and a thickening agent can be sprayed on surfaces contaminated with blood

traces. If catalyzed by metal ions, such as the iron contained in blood hemoglobin, the mixture will glow. Criminologists use luminol to identify microscopic blood drops invisible to the

naked eye. Luminol is widely used in biological and chemical research as a marker for iron, for determination of benzoyl peroxide in flour and more3, 4, 5, 6. It also helps to detect low

concentrations of hydrogen peroxide, proteins and DNA. Several methods have been proposed for the specific, sensitive and amplified detection of DNA utilizing chemiluminescence. Among them

is a rapidly progressing method to image biosensing events on surfaces, termed as electrogenerated chemiluminescence7. The primary advantage of chemiluminescence compared to the widely used

fluorescence8, 9 is the generation of photons during the course of a chemical reaction. In this case, the detected signal is not affected by external light scattering, source fluctuations or

high background due to nonresonant excitation10. Consequently, illuminometers based on light detection by photomultiplier tubes are among the cheapest devices in the field11. Here, we study

luminol flows in a microfluidic device. Microfluidic devices reduce liquid consumption, provide well-controlled mixing and particle manipulation, integrate and automate multiple assays

(known as lab-on-a-chip), and facilitate imaging and tracking12. The continuous flow injection provides improved mixing between the luminol and oxidant, resulting in a higher intensity of

emitted light than in a cuvette. The typical glow time when luminol is in contact with an activating oxidant is only ~30 s. However, flow injection allows a continuous glow as long as the

molecules and activating oxidants are pumped into the microfluidic chip. We report the first experimental evidence of the enhancement of the chemiluminescence intensity of luminol by the

introduction of metal nanoparticles in a microfluidic chip. Enhanced chemiluminescence intensity of luminol reacted with a weak oxidant, such as silver nitrate (AgNO3), in a microfluidic

chip has been observed under catalysis (i.e., speed up of a chemical reaction) by gold nanoparticles13. It was demonstrated that smaller nanoparticles (11 nm in diameter) give a stronger

chemiluminescence signal than larger ones (25 nm and 38 nm in diameter). To minimize the catalytic effect, we used nanoparticles 20 nm in diameter and larger. MATERIALS AND METHODS We have

designed and fabricated a reusable microflow device with a serpentine channel 600 μm in width, 200 μm in depth and 600 μm in length, formed in polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS). A diluted oxidant,

sodium hypochlorite (NaOCl), was injected into one part of the flow, and diluted luminol molecules were introduced into its other part. As a reference, we have been using 0.4 g of luminol

with 50 mg of NaOCl bleach and 4 g of the oxidant sodium hydroxide (NaOH) for 1950 ml of water; for the sample, we have been using 0.2 g of luminol with 50 mg of NaOCl bleach and 2 g of

oxidant NaOH for 1950 ml of water together with 50 ml of nanoparticles. The luminol solution was prepared either with or without nanospheres. The intensity of emitted light was detected by a

charge-coupled device (CCD), Lumenera Infinity 2-3C (Lumenera Corporation, 7 Capella Crt. Ottawa, Ontario, Canada). Figure 2 shows a schematic of the studied system: a microfluidic device

with syringes 180 μm in diameter that pump the fluid through a PDMS serpentine microchannel. It includes two inlets and one outlet. Luminol, NaOH, deionized water and nanoparticles were

pumped through the first inlet (Syringe 1 in Figure 2a), whereas NaOCl and water were injected through the second inlet (Syringe 2 in Figure 2a). The colloidal nanoparticles we used are

precisely manufactured monodisperse gold and silver nanoparticles from BBI Solutions (Kent, UK) suspended in water. They are passivated with polyethylene glycol to prevent aggregation. NaOH

and luminol are the constituent parts of the chemical reaction that generates light. Organic waste was discarded through the outlet liquid reservoir as shown in the schematic in Figure 2a.

During fabrication, the PDMS channel was molded over the 3D printed device. The layout for the mold was designed using the CAD Autodesk inventor (Stockport, UK). After printing, the channels

were sealed using oxygen plasma for 30 s. We analyzed the chemiluminescence spectra at different flow rates and different concentrations of luminol. The maximum chemiluminescence intensity

was obtained at the flow rate of 0.35 μl s−1. At higher flow rates, the reagent consumption was also increased compared to the slower flow rates. The limit of detection for the experimental

setup was determined using three standard deviations and 20 repeats of images for each individual point, obtaining <110 μg ml−1. The gold and silver nanoparticles investigated in this

study had radii _r_=10, 20 and 30 nm, as shown in Figure 2b. An artistic impression of the channel with gold nanoparticles is shown in Figure 2c. To achieve a better understanding of the

effect of gold and silver nanospheres on the efficiency of chemiluminescence emission by luminol, we performed spectrally resolved transmission measurements in the frequency range from 405

to 645 nm using a Jasco V570 spectrophotometer (28600 Mary's Ct, Easton, MD, USA) at room temperature as well as measurements of the chemiluminescence of luminol triggered by metallic

nanoparticles. RESULTS AND DISCUSSION Here, we observe enhancement of the chemiluminescence intensity of a luminol flow in the presence of metallic nanospheres on a microfluidic chip. The

experimental results captured by the CCD camera show a glowing serpentine channel in Figure 3a (left) compared to the barely seen serpentine channel in Figure 3a (right). In Figure 3a

(left), syringe 1 shown in Figure 2a was filled up with luminol in the presence of silver nanospheres of radii _r_=30 nm. Figure 3a (right) shows a typical reference photograph: the imaged

channel was filled with luminol without metal nanoantennas. The serpentine arms in Figure 3a and the emission intensity along the serpentine arms in Figure 3b are designated by roman

numerals. Figure 3b shows the change in the intensity of emission with the distance along the serpentine channel. The strongest enhancement occurs in arm II, which can be understood to

indicate the best mixing between reagents in this arm and/or the most favorable distance between the light-emitting species and nanoantennas. The mixing in the microfluidic chip occurs based

on the diffusion of particles from one laminar layer into the adjacent one. Efficient mixing occurs around the bends due to the Dean flow; therefore, arm II after the first bend shows the

highest chemiluminescence intensity, and the efficiency of the Purcell effect increases. The remaining serpentine arms exhibit an exponential decrease in chemiluminescence intensity due to

the chemiluminescence lifetime of the mixture. We have estimated the chemiluminescence lifetime of the mixture as a function of time, assuming an exponential decrease, in the serpentine arm

schematically shown in Figure 3c. The flow rate of luminol in the channel is as follows: The cross section of the channel is _S_=_πR_2 = 3.14(100 μm)2 =3.14 × 10−4cm2. The linear propagation

velocity of luminol is Veloity_x_= The characteristic length of the trajectory between two points along the serpentine channel, as shown in Figure 3, is 400 μm=4 × 10−2 cm, and thus the

time elapsed between two neighboring points on the graph is: _t_= = 4 × 10−2s=40 ms. The experiments were repeated with injected gold and silver nanoparticles with radii _r_=10, 20 and 30

nm, as illustrated in Figure 4. The maximal enhancement was observed for gold or silver nanospheres with _r_=30 nm. Sun _et al_14 analytically described the photoluminescence enhancement as

a result of the interplay of absorption and emission. It was shown14 that the increase in photoluminescence intensity due to the coupling to plasmonic modes is nonlinear with concentration

when the particle size is unchanged. However, we did not observe any increase in the intensity of emitted light upon changing the flow rate (volume per unit time, μl s−1) of injected

nanoparticles above 0.35 μl s−1. The maximum chemiluminescence intensity was obtained at flow rates of 0.35 μl s−1 and higher. The nonlinear increase in the intensity of chemiluminescence

emission as a function of concentration and the independence of the emission intensity on the flow rate in a wide range of flow rates do not support the possible explanation of the enhanced

chemiluminescence by the catalytic effect of metal. In our case, nanoparticles with ~_r_=30 nm provide the strongest enhancement of chemiluminescence. Figure 4a and 4b show the difference in

the emission intensity between the different serpentine arms. The intensity in each arm was calculated by summing the pixels. The results suggest that an enhancement of up to ninefold

occurs in arm II of the serpentine channel in the presence of silver nanospheres. Then, the signal exhibits an exponential decay. As shown in Table 1, however, the concentration of silver

nanoparticles is one order of magnitude lower than the concentration of gold. One can conclude that silver nanoparticles induce a higher enhancement of chemiluminescence than gold

nanoparticles. Therefore, the enhancement of luminol emission using silver nanospheres is stronger by a factor of up to 90 compared to using the same concentration of gold nanospheres. We

compare the transmission spectra of nanoparticles with the chemiluminescence emission intensity spectrum of luminol (Figure 5). The chemiluminescence spectrum of luminol exhibits two peaks

at wavelengths of 452 and 489 nm that correspond to the emission of excited aminophthalate ions either bound to water molecules or unbound. Both types of ions are products of the oxidation

of luminol. The molecular shape of luminol is shown by balls and sticks in the insets of Figure 5. Figure 5 shows a significant overlap15 between the absorption spectra of the acceptor16

metal nanospheres studied here and the chemiluminescence intensity spectrum of the donor luminol. This overlap suggests that the enhancement of chemiluminescence here could be induced by the

modification of the optical density of states in metallic nanoparticles in the vicinity of surface plasmon resonances17, 18. Notably, luminol emits at 452 and 489 nm (Figure 5), wavelengths

that can be reabsorbed by the nanosphere silver surface plasmon situated below 450 nm and the nanosphere gold surface plasmon situated above 500 nm, respectively. This situation is

favorable for the Purcell enhancement19 of the radiative emission rate mediated by plasmonic antennas. From Figure 6, the chemiluminescence emission peaks show spectral overlap with the

resonance absorption of the nanoparticles. Thus, the effect of resonant light emission20 enhancement, as shown in Figure 4, could be linked to the optical coupling between luminol molecules

and nanoparticles, just as a radio-antenna enhances radio emission21. The chemiluminescence intensity of luminol in the presence and in the absence of nanoparticles is shown in Figure 6a

(silver) and 6b (gold). The peaks of emission intensity at 452 and 489 nm are indicated by dashed lines. The presence of plasmonic nanoparticles changes the chemiluminescence characteristics

of luminol, leading to a multi-fold intensity enhancement as well as to the strong spectral modification of the chemiluminescence emission peaks. For instance, for silver nanoparticles with

_r_=30 nm, the chemiluminescence peak is enhanced, and the emission peak of the luminol at 452 nm is modified. Here, the resonant absorption peak of silver nanoparticles overlaps

substantially with the luminol emission peak at 452 nm (see the absorption spectrum shown by the blue dashed line). This overlap suggests that the enormous chemiluminescence enhancement

results from the interaction between excited-state luminol and the ensemble of optical modes in the system. A source of light (a luminol molecule in our case) emits photons to a medium

characterized by some given density of photonic states. If at the emission frequency this density is lower than in vacuum, the radiative efficiency is increased. In the presence of metallic

nanoparticles, the density of photonic states increases resonantly at certain characteristic frequencies associated with the plasmon modes of metallic objects. If the emission band of

luminol overlaps with the spectral region of the plasmon-induced increase in the photonic density of states in the medium, the radiative efficiency of luminol is enhanced. We attribute this

result to the Purcell enhancement19 of the radiative recombination rate of luminol molecules. The Purcell factor _F_p is governed by the overlap of the emission spectrum of luminol and the

absorption band of metallic nanoparticles. The most efficient Purcell enhancement of the radiative recombination is observed if the emission wavelength is resonant with the plasmon

absorption peak in the antennas22. Such coupling between the emitter and the nanoparticle surface plasmon must be sensitive to the particle material (gold or silver), the particle size and

the spacing between the emitting luminol molecule and the nearest nanoparticle. If the plasmon resonance in a nanoparticle is blue-shifted due to the smaller radius of the particle, the

chemiluminescence spectrum is weakened and broadened near 452 nm. In the case of gold nanoparticles, by reducing the radius of the particle, the chemiluminescence spectrum is weakened and

sharpened near 489 nm. In all cases, the chemiluminescence emission spectrum is shifted from its original position towards the nanoparticle wavelength corresponding to the resonant

absorption of the particle. In addition, the presence of a strong interactor, metal, in the microfluidic chip could induce the shift in the emission spectrum of luminol. The enhancement

mechanisms of chemiluminescence emission are illustrated in Figure 723. In the case of luminol, radiative recombination could compete with non-radiative decay processes24. There is little

light emitted in the course of a chemiluminescence reaction because the probability of emitting a photon is much lower than the probability of decaying through a non-radiative channel (e.g.,

by collisions or resonant energy transfer to another molecule). This case is the typical one where nanoantennas are useful25. Indeed, they can introduce a fast decay channel for the

luminophore that can compete with the non-radiative processes, which are otherwise much faster than photon emission processes. In the presence of metallic nanospheres, the very low quantum

yield of luminol molecules, _η_CL =0.001–0.1, could be replaced by the higher quantum yield of metallic particles, which depends on the radius and the material (gold or silver) of the

nanosphere. The glow of luminol is a manifestation of chemiluminescence: light emission resulting from an exothermic chemical reaction. Spontaneous emission can be enhanced by the presence

of metal nanoparticles. Chemiluminescence can also be amplified by chemical catalysis26, e.g., by nanostructure-induced catalysis enhancement27, 28 or optically by using resonant structures,

such as nanoantennas, quantum dot metamaterials22 or silver islands29. The overall efficiency of chemiluminescence, _η_, can be expressed as _η_=_η_C _η_e_η_F, where _η_C is the fraction of

reacting molecules that may be excited, and _η_e is the percentage of molecules that actually are excited. This value describes the efficiency of the energy transfer. Finally, _η_ = is the

quantum yield of the emitter7, where _η_F accounts for the probability of radiative decay for a single molecule, and _γ_R and _γ_NR are the radiative and non-radiative decay rates,

respectively. Chemiluminescence is limited in efficiency because excited molecules can lose their energy through non-radiative processes, such as internal conversion and intersystem

crossing. An excited molecule can decay either radiatively at the rate _γ_R or non-radiatively at the rate _γ_R. These competing effects are schematically depicted in Figure 7a. In the

presence of nanoantennas30 (Figure 7b), the initial population of excited molecules can decay radiatively at the rate _Γ_R or non-radiatively at the rate _Γ_R. In the last case, the ratio of

radiative and non-radiative decay rates can be changed. The non-radiative decay rate of luminol in the presence of nanoantennas is modified by non-radiative energy transfer to the antenna,

as shown in Figure 7b. The chemiluminescence emission enhancement and spectral shape can also be modified by the far-field scattering mechanism schematically presented in Figure 7c. The

quantitative description of the mechanism of chemiluminescence enhancement will be studied in our future work. CONCLUSIONS In conclusion, we have demonstrated multi-fold enhancement of the

chemiluminescence intensity during flow injection in a microfluidic chip. We have observed that pumping nanoparticles into a microfluidic device fabricated in PDMS prolongs the glow time of

luminol. The enhancement of chemiluminescence by metallic nanoparticles may be due to the following factors: (i) the uniform intensity of chemiluminescence emission due to thorough mixing of

the reagents and maximized intensity due to the location of emitters at distances that are favorable for interaction with the metal nanoparticles (antennas) and (ii) the collective response

of conduction electrons in the metal. The optical field of plasmon modes is localized in the vicinity of the surfaces of metallic nanoparticles. As a result, the lightning antenna effect

exhibits resonant amplification if the excitation frequency coincides with a localized surface plasmon resonance of the particle. We have proposed two possible mechanisms for

chemiluminescence enhancement during flow injection. (i) The rate of emission by a chemophore emitter can be enhanced by an antenna effect. The Purcell effect may be responsible for the

amplification of the radiative decay rate due to the enhanced density of optical states accessible for decay of the molecular excitation. (ii) The observed enhancement and modification of

the spectral shape could also be due to far-field scattering. The observed chemiluminescence enhancement provides the first demonstration of a resonant enhancement of luminol flow in the

presence of nanoparticles. From a technological perspective, the use of microfluidic devices (i) reduces the luminol consumption, (ii) controls mixing and (iii) controls the concentration of

nanoparticles. This innovation is important for achieving uniform emission intensity and the favorable location of emitting species with respect to the nanoparticles. We have integrated the

chemiluminescence analysis setup on a chip (known as lab-on-a-chip) to facilitate imaging. Our observations indicate that noble metal nanoparticles can readily be used to enhance

chemiluminescence even in microvolume samples. This observation is an essential step toward developing microfluidic chips with gain media and toward improving the detection limits of

chemiluminescence. REFERENCES * Barni F, Lewis SW, Berti A, Miskelly GM, Lago G . Forensic application of the luminol reaction as a presumptive test for latent blood detection. _Talanta_

2007; 72: 896–913. Article Google Scholar * White EH, Zafiriou O, Kägl HH, Hill JM . Chemiluminiscence of luminol: the chemical reaction. _J Am Chem Soc_ 1964; 86: 940–941. Article Google

Scholar * Daniel MC, Astruc D . Gold nanoparticles: assembly, supramolecular chemistry, quantum-size-related properties, and applications toward biology, catalysis, and nanotechnology.

_Chem Rev_ 2003; 104: 293–346. Article Google Scholar * Campbell AK . _Chemiluminescence: Principles and Applications in Biology and Medicine. Series in Biomedicine_. Chichester: Ellis

Horwood Ltd.; 1988. Google Scholar * Bhattacharyya A, Klapperich CM . Design and testing of a disposable microfluidic chemiluminescent immunoassay for disease biomarkers in human serum

samples. _Biomed Microdevices_ 2007; 9: 245–251. Article Google Scholar * Liu W, Zhang ZJ, Yang L . Chemilummescence microfluidic chip fabricated in PMMA for determination of benzoyl

peroxide in flour. _Food Chem_ 2006; 95 : 693–698. DOI: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2005.04.005. Article Google Scholar * Patolsky F, Katz E, Willner I . Amplified DNA detection by electrogenerated

biochemiluminescence and by the catalyzed precipitation of an insoluble product on electrodes in the presence of the doxorubicin intercalator. _Angew Chem Int Ed_ 2002; 41: 3398–3402.

Article Google Scholar * Karabchevsky A, Khare C, Patzig C, Abdulhalim I . Microspot biosensing based on surface enhanced fluorescence from nano sculptured metallic thin films. _J

Nanophoton_ 2012; 6: 1–12. Google Scholar * Abdulhalim I, Karabchevsky A, Patzig C, Rauschenbach B, Fuhrmann B _et al_. Surface enhanced fluorescence from metal sculptured thin films with

applications to biosensing. _Appl Phys Lett_ 2009; 94: 1–3. Article Google Scholar * Dodeigne C, Thunus L, Lejeune R . Chemiluminescence as diagnostic tool. A review. _Talanta_ 2000; 51:

415–439. Article Google Scholar * Van Dyke K, McCapra F, Behesti I . _Bioluminescence and Chemiluminescence Instruments and Applications_. Boca Raton: CRC Press; 1985. Google Scholar *

Sackmann EK, Fulton AL, Beebe DJ . The present and future role of microfluidics in biomedical research. _Nature_ 2014; 507: 181–189. Article ADS Google Scholar * Kamruzzamann M, Alam AM,

Kim KM, Lee SH, Kim YH _et al_. Chemiluminescence microfluidic system of gold nanoparticles enhanced luminol-silver nitrate for the determination of vitamin B12. _Biomed Microdevices_ 2013;

15: 195–202. Article Google Scholar * Sun G, Khurgin JB, Soref RA . Practical enhancement of photoluminescence by metal nanoparticles. _Appl Phys Lett_ 2009; 94: 101103. Article ADS

Google Scholar * Lakowicz JR . _Principles of Fluorescence Spectroscopy_. New York: Springer; 2006. Book Google Scholar * Ghosh D, Chattopadhyay N . Gold nanoparticles: acceptors for

efficient energy transfer from the photoexcited fluorophores. _Opt Phot J_ 2013; 3: 18–26. Article Google Scholar * Stefani FD, Vasilev K, Bocchio N, Stoyanova N, Kreiter M .

Surface-plasmon-mediated single-molecule fuorescence through a thin metallic film. _Phys Rev Lett_ 2005; 94: 23005–23009. Article ADS Google Scholar * Lee J, Govorov AO, Dulka J, Kotov NA

. Bioconjugates of CdTe nanowires and Au nanoparticles: plasmon-exciton interactions, luminescence enhancement, and collective effects. _Nano Lett_ 2004; 4: 2323–2330. Article ADS Google

Scholar * Purcel EM . Spontaneous emission probabilities at radio frequencies. _Phys Rev_ 1946; 69: 681–681. Google Scholar * Aslan K, Geddes CD . Metal-enhanced chemiluminescence:

advanced chemiluminescence concepts for the 21st century. _Chem Soc Rev_ 2009; 38: 2556–2564. Article Google Scholar * Greffet JJ . Nanoantennas for light emission. _Science_ 2005; 308:

1561–1563. Article Google Scholar * Tanaka K, Plum E, Ou JY, Uchino T, Zheludev NI . Multifold enhancement of quantum dot luminescence in plasmonic metamaterials. _Phys Rev Lett_ 2010;

105: 227403. Article ADS Google Scholar * Jouanin A, Hugonin JP, Besbes M, Lalanne P . Improved light extraction with nano-particles offering directional radiation diagrams. _Appl Phys

Lett_ 2014; 104: 021119. Article ADS Google Scholar * Carminati R, Greffet JJ, Henkel C, Vigoureux JM . Radiative and non-radiative decay of a single molecule close to a metallic

nanoparticle. _Opt Commun_ 2006; 261: 368–375. Article ADS Google Scholar * Kurgin JB, Sun G, Soref RA . Enhancement of luminescence efficiency using surface plasmon polaritons: figures

of merit. _J Opt Soc Am_ 2007; 24: 1968–1980. Article MathSciNet Google Scholar * Zhang ZF, Cui H, Lai CZ, Liu LJ . Gold nanoparticle-catalyzed luminol chemiluminescence and its

analytical applications. _Anal Chem_ 2005; 77: 3324–3329. Article Google Scholar * Lu GW, Shen H, Cheng BL, Chen ZH, Marquette CA _et al_. How surface-enhanced chemiluminescence depends on

the distance from a corrugated metal film. _Appl Phys Lett_ 2006; 89: 223128. Article ADS Google Scholar * Lu GW, Cheng BL, Shen H, Chen ZH, Yang GZ _et al_. Influence of the nanoscale

structure of gold thin films upon peroxidase-induced chemiluminescence. _Appl Phys Lett_ 2006; 88: 023903. Article ADS Google Scholar * Eltzov E, Prilutsky D, Kushmaro A, Marks RS, Geddes

CD . Metal-enhanced bioluminescence: an approach for monitiroing luminescent processes. _Appl Phys Lett_ 2009; 94: 083901. Article ADS Google Scholar * Agio M, Cano DM . Nano-optics: the

purcell factor of nanoresonators. _Nat Photonics_ 2013; 7: 674–675. Article ADS Google Scholar Download references ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS AVK acknowledges support from the EPSRC established

career fellowship, and AK acknowledges support from the BGU (Israel) Outstanding Woman in Science Award. Special thanks to Jean-Jacques Greffet for the analysis of results and stimulating

discussions. The fruitful discussions with Jean-Paul Hugonin are also highly appreciated. AUTHOR INFORMATION AUTHORS AND AFFILIATIONS * Electrooptical Engineering Unit and Ilse Katz

Institute for Nanoscale Science & Technology, Ben-Gurion University, Beer-Sheva, 84105, Israel Alina Karabchevsky * Engineering Sciences Unit, Engineering and the Environment, University

of Southampton, Southampton, SO17 1BJ, UK Ali Mosayyebi * Department of Physics and Astronomy, University of Southampton, Southampton, SO17 1BJ, UK Alexey V Kavokin * Viale del Politecnico

1, Rome, I-00133, CNR-SPIN, Italy Alexey V Kavokin Authors * Alina Karabchevsky View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Ali Mosayyebi View

author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Alexey V Kavokin View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar

CORRESPONDING AUTHOR Correspondence to Alina Karabchevsky. RIGHTS AND PERMISSIONS This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. The images or other

third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative

Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Reprints and permissions ABOUT THIS ARTICLE CITE THIS ARTICLE Karabchevsky, A., Mosayyebi, A. & Kavokin, A. Tuning the chemiluminescence of a luminol flow using plasmonic nanoparticles.

_Light Sci Appl_ 5, e16164 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1038/lsa.2016.164 Download citation * Received: 07 October 2015 * Revised: 20 April 2016 * Accepted: 10 May 2016 * Published: 19 May

2016 * Issue Date: November 2016 * DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/lsa.2016.164 SHARE THIS ARTICLE Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content: Get shareable link

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article. Copy to clipboard Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative KEYWORDS * chemiluminescence *

microfluidics * nanoparticles * plasmonics