Scalable integration of nano-, and microfluidics with hybrid two-photon lithography

- Select a language for the TTS:

- UK English Female

- UK English Male

- US English Female

- US English Male

- Australian Female

- Australian Male

- Language selected: (auto detect) - EN

Play all audios:

ABSTRACT Nanofluidic devices have great potential for applications in areas ranging from renewable energy to human health. A crucial requirement for the successful operation of nanofluidic

devices is the ability to interface them in a scalable manner with the outside world. Here, we demonstrate a hybrid two photon nanolithography approach interfaced with conventional mask

whole-wafer UV-photolithography to generate master wafers for the fabrication of integrated micro and nanofluidic devices. Using this approach we demonstrate the fabrication of molds from

SU-8 photoresist with nanofluidic features down to 230 nm lateral width and channel heights from micron to sub-100 nm. Scanning electron microscopy and atomic force microscopy were used to

characterize the printing capabilities of the system and show the integration of nanofluidic channels into an existing microfluidic chip design. The functionality of the devices was

demonstrated through super-resolution microscopy, allowing the observation of features below the diffraction limit of light produced using our approach. Single molecule localization of

diffusing dye molecules verified the successful imprint of nanochannels and the spatial confinement of molecules to 200 nm across the nanochannel molded from the master wafer. This approach

integrates readily with current microfluidic fabrication methods and allows the combination of microfluidic devices with locally two-photon-written nano-sized functionalities, enabling rapid

nanofluidic device fabrication and enhancement of existing microfluidic device architectures with nanofluidic features. SIMILAR CONTENT BEING VIEWED BY OTHERS SPATIALLY AND OPTICALLY

TAILORED 3D PRINTING FOR HIGHLY MINIATURIZED AND INTEGRATED MICROFLUIDICS Article Open access 17 September 2021 MOLD-FREE SELF-ASSEMBLED SCALABLE MICROLENS ARRAYS WITH ULTRASMOOTH SURFACE

AND RECORD-HIGH RESOLUTION Article Open access 07 June 2023 DIRECT ELECTRIFICATION OF SILICON MICROFLUIDICS FOR ELECTRIC FIELD APPLICATIONS Article Open access 19 June 2023 INTRODUCTION

Micro and nanofabrication give new possibilities to analyze molecular processes with high precision. Microfluidics1 has for instance become a powerful tool to study biological systems at

single cell resolution2,3,4 and has allowed the observation of single molecules5,6,7 and of single nucleation events in protein aggregation8 in a controllable environment. Microdroplet

generation9, microfluidic diffusional sizing10,11,12, and electrophoresis on chip13,14,15 are now established techniques, but the nanofluidic regime has the potential to open up a new set of

possibilities applications16,17,18. Many specific physical features motivate the interest in nanofluidic device fabrication, including the existence of selective transport mechanisms

occurring when channel widths reach diameters close to the Debye length19,20. Interactions between protein charges and the Debye layer can be used to confine, separate, and concentrate

proteins21 as well as sorting exosomes and colloids according to their size down to 20 nm22. Moreover, nanofluidics has the potential to provide increased efficiencies in blue energy, where

osmotic power is harvested from Gibbs free energy of a salt gradient between two solutions connected by nanopores, nanochannels, or membranes23. Performance of reverse electrodialysis

depends on the scale and geometry of the nanoscale confinement used, as has been studied24,25 in cylindrical and conical shaped nanochannels down to tens of nanometers. Currently, to produce

lab-on-chip devices in the nanofluidic regime, electron beam lithography (EBL) and focused ion beam etching are used in clean room facilities to prototype nanochannels or nanopores in the

sub-100 nm range in silicon/silicon nitride26. EBL can achieve channel sizes smaller than 10 nm27, but cannot pattern as fast as mask-based lithography approaches28. These approaches work

well, but can be challenging to integrate with microfluidics and are costly and can require long writing times. Here, we demonstrate an approach to produce nanofluidic chips at wafer-scale

in a nonclean room environment using a hybrid lithography approach bringing together direct two photon writing for defining nanoscale structures with conventional whole-wafer mask

ultraviolet (UV) lithography. The adoption of microfluidic technologies has been substantially accelerated by soft-lithography approaches29 and currently common practice for lab-on-a-chip

device fabrication on a laboratory scale is UV mask photolithography followed by soft lithography. There are two main photolithographic strategies to produce master molds for soft

lithography—large area mask patterning and direct laser-writing (DLW)30,31. In general, both techniques work with UV-curable photoresists such as SU-8 spincoated onto a silicon wafer, with

specified thicknesses of tens of microns. Uncross-linked SU-8 is soluble in the developing agent PGMEA but becomes cross-linked and insoluble when exposed to UV radiation and post-exposure

heat treatment. UV attenuating masks with transparent sections in areas to be solidified are brought between the light source and the wafer to project microfluidic chip designs onto the

photoresist coated wafer. Unilluminated areas are afterwards dissolved during the development process and only the UV-exposed areas remain. The wafer surface then is used as a mold for soft

lithography using PDMS casting. DLW has the advantage that there is no need for masks. In this approach a laser is scanned over the wafer and is modulated accordingly to write the intended

pattern. Both of these technologies are restricted by the diffraction limit and their patterning capabilities are conventionally limited by the thickness of the photoresist between 5 and 120

µm for common microfluidic fabrication because exposure triggers polymerization throughout the thickness of the photoresist. Two-photon lithography overcomes these limitations by using high

power femtosecond pulse laser sources operating at twice the absorption wavelength used for the conventional DLW process. Two such high wavelength low-energy infrared radiation (IR) photons

can interact with the photoinitiator molecule if they arrive within the very short lifetime of the virtual state created by the interaction of the first photon with the absorbing molecule

in the photoresist32. This effect is thus strongly dependent on the power of the incident radiation33. In two-photon lithography, polymerization only takes place when the square of the

incident power reaches a threshold, unlike for conventional single photon lithography where polymerization is controlled by the intensity itself. Since the volume in which the square of the

intensity is above a critical threshold can be smaller than the volume in a diffraction limited focused laser, sub-diffraction limited features can be generated. Considering an additional

nonlinear photo response of the photoresist materials itself and adjusting the laser intensity close to the energy threshold for polymerization, SU-8 nanorods of about 30 nm have previously

been presented34. The fact, that two incoming photons are unlikely to interact with a photoinitiator molecule at the same time before reaching the focal spot opens up arbitrary sectioning

capabilities within the spincoated photoresist layer thickness. The application range of two-photon lithography ranges from the fabrication of photonic crystals35, cell scaffolds36 to

metamaterials37, biomimicry38, and additive manufactured microfluidics39. Two-photon lithography has been used40 to incorporate optical components (e.g., a total internal reflecting mirror)

with a microfluidic channel using soft lithography and to demonstrate the integration of a three-dimensional microfluidic mixer into photolithographically fabricated areas on a glass

coverslip41. In this paper, we enhance the strategy of combining conventional UV lithography with two-photon direct laser writing to approach the nanofluidic regime on a silicon surface.

Silicon wafers are more common for microfluidic master fabrication than glass coverslips, due to their mechanical strength and surface quality. In the following, we introduce and

experimentally demonstrate the successful master fabrication of nanofluidic chip devices on a silicon wafer using standard SU-8 with a channel size of 420 nm and show that arbitrary height

channel mold fabrication down to 50 nm is possible. A custom-built two-photon setup was characterized with a calibration assay to determine the achievable minimal feature size of the system.

Three system parameters were systematically evaluated to define the achievable resolution of the writing process: laser power, scanning speed, and focal spot offset from the wafer surface.

To find the optimal values of these, test gratings were written in SU-8 at different conditions. Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) and atomic force microscopy (AFM) for the characterization

of the polymerized features and the evaluated parameters, were used to incorporate nanofluidic channels into a microfluidic master. To show the successful imprinting of nanofluidic PDMS

devices, their fluidic connectivity was demonstrated by flowing Rhodamine 6G dye through the channels and imaging their lateral width on chip, using super-resolution microscopy. The

procedure presented here, fills the gap of affordable nanofabrication in biological laboratories in combination with conventional UV lithography—overcoming low patterning speeds of

DLW-technology but achieving subdiffraction features in areas of interest. RESULTS COMBINING UV LITHOGRAPHY WITH TWO-PHOTON DLW FOR WAFER-SCALE NANOFLUIDIC CHIP FABRICATION To explore the

integration of nanofluidics with microfluidics we focus on a prototypical nano/micro device, consisting of two microfluidic channels that are connected via nanochannel junctions. These can

be used for instance to isolate single molecules from a solution and study their diffusion properties. On one side a sample solution is pumped through, while the other compartment of the

device will be exposed to particles or proteins that fit through the nanosized restriction connecting them. Conventional methods to produce such nanofluidic devices are based on spincoating

of sub-100 nm thin photoresist films and exposure through UV attenuating masks or require electron beam lithography to push the lateral width down to the nanoscale42. Practical limitations

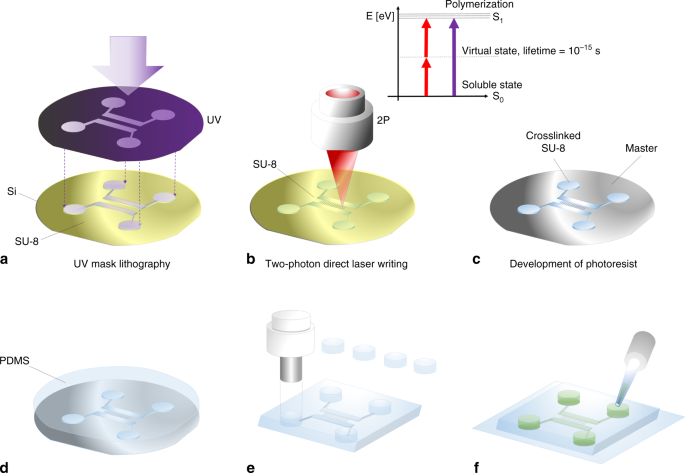

of these methods are long writing times and variations in the photoresist thickness that render the integration of nanofluidics difficult. In our procedure presented here (see Fig. 1a–f), we

can use a single spin-coating process of a thick (e.g., 25 µm) SU-8 layer to fabricate nanofluidic master molds on a silicon wafer (Supplementary Figs. 1 and 2). The wafer is prebaked to

remove solvent and UV-exposed through a film mask to pattern microfluidic areas on a waferscale. The wafer was then postbaked to polymerize the irradiated areas. The baking process induces a

refractive index difference between exposed and unexposed areas. These refractive index edges were then used in the two-photon setup to find the regions of interest on the microfluidic

master wafer, where the nanojunctions should be written. Since two-photon polymerization is induced only in the focal spot, we have arbitrary control over the height of the printed

channels—we overcome the drawbacks of conventional necessary multiple spincoating steps and fabricate devices within one development process. In a second step the master wafer is developed

in PGMEA, cleaned with isopropanol and dried using pressurized nitrogen. Through soft lithography, we imprinted the pattern of the functionalized nanofiltration chips in PDMS. The final PDMS

imprint with additional microfluidic prefiltration section can be seen in Fig. 2a. SEM images reveal the successful connection of the two microchannels with nanochannels of 420 nm width and

75 microns in length (see Fig. 2b, c). Due to double exposure by UV lithography and two-photon writing the nanochannels show broader joints at the intersection with the microfluidic area.

CALIBRATION ASSAY FOR MICRO-, TO NANO-SCALE 2-PHOTON WRITING Since two-photon polymerization is a dose dependent process, the polymerized voxel scales with the intensity and the scanning

speed of the laser beam in the photoresist. In addition, since 2PL is used here for 2.5 dimensional fabrication, the voxel truncation by the wafer surface also plays an important role on the

lateral size of the written lines. A systematic approach was employed to evaluate the key factors in the system and define suitable operation parameters for micro-, to nano-sized two-photon

writing on the wafer surface. Faster scanning speed as well as lower laser intensity were observed to result in a smaller voxel size. Voxel truncation influences both and is furthermore

important for the height of the channel molds and proper attachment of the polymerized resin. We evaluated powers ranging from 50 to 120 mW measured after the acousto-optic modulator and

ascending of the laser focus into the wafer from 0 to 3 µm at a constant writing speed of 400 µm/s. An SEM image of the calibration print can be seen in Fig. 3a. To improve SEM image quality

and contrast, the sample was coated with 10 nm platinum. Along the vertical axis the laser power for each line was varied, where the highest intensity was used at the top line. As expected,

with increasing laser power the voxel size increases from bottom to top. At the lower end the effective laser dose did not reach the polymerization energy threshold, which results in no

polymerization to occur. From left to right, a decrease in lateral width can be observed due to the laser focus being lowered 3 µm into the wafer over a distance of 100 µm. Using this

calibration map, suitable parameters can be read out and the spot size adjusted according to the filling factor of the pattern—or in this case—the channel dimensions to be written. We found

soft lithography compatible structures down to a size of 280 nm lateral width as shown by SEM imaging in Fig. 3b and even 230 nm if the optical design is adopted (Supplementary Fig. 3). AFM

measurements of the region show heights down to 360 nm and are illustrated in Fig. 3c along with height profile measurements in Fig. 3c*. Two-photon written nanochannels are by nature of

hyperbolic shape32, assuming a Gaussian intensity distribution in the focal spot, which limits this technology for the fabrication of rectangular channels. In comparison with other

nanolithography techniques the achievable lateral widths are relatively large but AFM measurements at positions where the voxel is about to disappear into the sample, verified a height of

down to 52 nm (see Fig. 3b*) and 35 nm height (Supplementary Fig. 4). Precise height control of the sample is required to approach fabrication in this regime due to nonlinear behavior of the

channel height when truncating the voxel on the surface (Supplementary Fig. 5). We found that high spatial frequency components of the focused laser beam interfere above the wafer surface

and result in multiple polymerization locations which can lead to detachment of the structures during the development process. Reducing the beam diameter before the objective resulted in an

improvement of fabrication quality—showing similar lateral resolution and smooth lines when ascending the voxel into the wafer (Supplementary Fig. 6). TIRF-SUPER-RESOLUTION IMAGING OF

RHODAMINE 6G MOLECULES IN NANOCHANNELS In order to test the fluidic connectivity of the nanofluidic devices, we flushed from the microfluidic inlet, (A) in Fig. 4, an aqueous solution of a

dye. Since the channels’ dimensions are of the order or smaller than the wavelength of light, we used super resolution microscopy to image the nanofluidic channels. To this effect, total

internal reflection (TIRF) illumination was used to restrict the excitation area of a fluorescence microscope to an area of approximately 100 nm above the coverslip. Since out of focus

fluorophores are not excited, this technique has much higher signal to noise ratio and is perfectly suitable for nanochannel measurements due to spatial confinement of molecules close to the

coverslip and allows the observation of single fluorescent molecules diffusing into the nanochannels from the reservoirs (Supplementary video 1). To verify the correct bonding and size

consistency of the channels on chip we filled the reservoirs with Rhodamine 6G solution at femto molar concentration dissolved with 200 mM MEA in phosphate-buffered saline. The solution was

adjusted with KOH to a pH of 10 in order to induce blinking of the fluorescent dye molecules and enable breaking the resolution limit of conventional fluorescence microscopy by using the

STORM principle43. By taking thousands of images, localizing the fluorescent emitters in each image and overlaying the data, a super resolved image can be reconstructed. A description of the

setup that was used for imaging can be found in Rowlands et al.44. Single molecule localization is a useful method for the characterization of nanofluidic devices after the plasma bonding

step to verify fluidic connectivity and offers an alternative to clean room equipment such as electron microscopy or AFM. From the super-resolved fluorescence microscopy image the effective

channel size was measured to be 200 nm (full width at half maximum) (see Fig. 4a, b), and is consistent with the expected channel size read out from the calibration data acquired by SEM and

demonstrates the reliability of this technique. Small distortions induced by sample handling during the bonding process can be visualized on chip and imply the importance of careful handling

of the PDMS during the bonding process. The detected molecules show a Gaussian distribution along the channel width, which could be due to the increased channel height toward the

nanochannel center. This caused an increase in the amount of detected molecules in the center in comparison to positions close to the walls. DISCUSSION In this paper we show that two-photon

lithography can be used to fabricate nanofluidic channels of arbitrary heights from micron to sub-100 nm using materials conventionally employed for microfluidic fabrication and to integrate

these structures with microfluidics. Two-photon lithography provides a reliable technique that decouples the influence of varying photoresist thicknesses from nanofluidic fabrication. The

method reaches the upper boundary of the ultrananoscale with 35–50 nm channel heights, where new charge induced transport mechanisms start to appear, but remains in lateral resolution one

order of magnitude larger than EBL and RIE. Also the round shape of the polymerization voxel inhibits the fabrication of rectangular shaped channels which is achievable using RIE. Another

technique, e.g., crack induced nanochannels—provides a simple and nonclean room technique with channel sizes in the sub-100 nm regime. Approaches such as generating mechanically induced

cracks in chips have a high fabrication speed and can rapidly generate nanochannels up to mm length. However, this method cannot be easily interfaced with traditional PDMS microfluidics. The

combination of EBL and UV lithography is possible, but it is challenging without extending write times and costs, whereas 2PL provides high flexibility for the effective integration of

arbitrary two-dimensional nanofluidic functionalities into microfluidic masters. Although two-photon lithography cannot achieve as small features as electron-beam lithography, its

fabrication range is useful for a variety of biophysical and blue energy applications, e.g., charge measurements of proteins in solution using nanotraps with dimensions of 600 nm width and

160 nm height46. Nano-electroporation uses 90 nm wide channels for precise dose control for the injection of nanoparticles, plasmids and siRNA on a single cell basis and demonstrate the

improvement of the process when channels in the submicron regime are used47. A nanofluidic power generator device of a power density of 705 W/m2 using a KCl concentration gradient in a

nanochannel of the dimensions 715 nm × 350 nm × 40 nm was demonstrated by Zhang et al.48—fabricated in a silicon chip. However, care must be taken when comparing softlithography devices with

silicon applications. Handling the PDMS carefully during the bonding process is crucial to not bend or collapse nanostructures on the final substrate. Silicon chips are more reliable and

stable during operation, but PDMS is cost-effective and offers the advantage of fast replacement. The lateral resolution of the two-photon effect can be pushed to the limit by using the STED

principle.49 Using photoresists consisting of tri- and tetra-acrylates and 7 diethylamino-3-thenoylcoumarin and surrounding the focal spot with a depletion beam pushes the polymerized

features size to 55 nm at a resolution of 120 nm, which shifts two-photon lithography technology further towards EBL resolution for nanofabrication. METHODS SAMPLE PREPARATION AND

DEVELOPMENT In all, 25 µm of SU-8 were spin coated (BRUKER) at 3000 rpm onto a silicon wafer. The wafer was soft baked and treated according to the protocol of the photoresist distributor

(Microchem). A microfluidic mask pattern was then projected onto the photoresist for 50 s with the setup described in Challa et al.50. The wafer post baked at 95 °C so that the interfaces

between developed and undeveloped regions become visible. After the two-photon writing process the whole wafer was again baked at 95 °C and finally rinsed with PGMEA and IPA. TWO-PHOTON

LITHOGRAPHY SETUP To produce the high intensities needed for two photon excitation to occur, a Menlo System C-Fiber 780 HP Er:doped fiber oscillator with a repetition rate of 100 MHz with

integrated amplifier and second harmonic generation was used as light source of the two photon system. The laser pulse width is 120 fs. The setup is optimized to produce nanoscale features

on a 100 µm × 100 µm field. The beam is expanded to fill the whole back aperture of the objective lens (Leica, PL APO, Magn. 100×, NA = 1.4, oil) using a Thorlabs beam expander (AR coated:

650–1050 nm, GBE05-B). To make positioning of the focal spot over a whole 3″ wafer possible, two PI linear-precision stages (M-404.2PD, Ball screw, 80 mm wide, ActiveDrive) were mounted

perpendicular on top of each other with a suitable adaptor plate, connected to two individual PI Mercury DC Motor Controllers (C-863.11, 1 Channel, wide range power supply). On top, a PI

NanoCube with a travel range of 100 µm × 100 µm × 100 µm is mounted for high precision movement (pos. resolution: 1 nm) of the sample during the writing process. We focus on the

wafer/photoresist interface using the back-reflection of the laser beam at low intensity (where polymerization will not occur), and capture the image via a USB-camera (µEye ML, Industry

camera, USB 3.0) with a tube lens (Thorlabs AC 254-100-A-ML, BBAR coating 400–700 nm, _f_ = 100.0 mm) mounted above the objective. The objective is mounted onto a Thorlabs Z812B stage to

allow wider travel range in _z_ when moving over the wafer. The laser modulation is controlled by an acousto-optic modulator by AA Optoelectronics mounted after the laser output port

connected to a fast switching power supply (ISOTECH,DC power supply, IPS 33030). In order to provide an open-source setup all the control programming is realized in Python as well as the

automated writing of a calibration assay of the system. CONCLUSION We integrated successfully nanofluidic functionalities into microfluidic devices by combining two-photon lithography with

mask based UV lithography on a silicon wafer. Pre-exposed areas generated first through conventional UV lithography undergo a refractive index change which can then be used to align the

two-photon writing process. We showed that the two-photon lithography setup presented here is capable of producing features down to 230 nm lateral width on a silicon wafer surface in SU-8

photoresist and successfully integrated 420 nm wide nanochannels into a microfluidic master design. By ascending progressively the exposure voxel, reliable nanochannel molds of sub 100 nm in

height were fabricated. This regime has the potential to produce PDMS devices that are comparable to EBL or RIE-etched chips. In contrast to other techniques e.g nanochannel fabrication by

cracking, where mechanics and reagents define the shape of the formed nano junctions – two-photon lithography allows the integration of arbitrary nano-sized patterns and complex shapes

including varying channel sizes into microfluidic devices. We verified the reliability of the fabrication process by comparing SEM images of a SU-8 calibration sample with TIRF fluorescence

super-resolution imaging in the final PDMS devices. Further improvements in resolution of the process could be achieved by a change in photoresist composition or post-processing of the

photoresist via temperature and plasma treatment to thin out written structures. We hope to provide with this method a fast, reliable and flexible pathway for nanofluidic device fabrication

to enable readily the addition of nanofluidic features to conventional devices. REFERENCES * Whitesides, G. M. The origins and the future of microfluidics. _Nature_ 442, 368–373 (2006).

arXiv:1011.1669v3. Article Google Scholar * Klein, A. M. et al. Droplet barcoding for single-cell transcriptomics applied to embryonic stem cells. _Cell_ 161, 1187–1201 (2015). Article

Google Scholar * Macosko, E. Z. et al. Highly parallel genome-wide expression profiling of individual cells using nanoliter droplets. _Cell_ 161, 1202–1214 (2015). Article Google Scholar

* Croote, D., Darmanis, S., Nadeau, K. C. & Quake, S. R. Antibodies cloned from single. _Science_ 1309, 1306–1309 (2018). Article Google Scholar * Huang, S., Romero-Ruiz, M., Castell,

O. K., Bayley, H. & Wallace, M. I. High-throughput optical sensing of nucleic acids in a nanopore array. _Nat. Nanotechnol._ 10, 986–991 (2015). Article Google Scholar * Bell, N. A.

& Keyser, U. F. Digitally encoded DNA nanostructures for multiplexed, single-molecule protein sensing with nanopores. _Nat. Nanotechnol._ 11, 645–651 (2016). Article Google Scholar *

Chen, K. et al. Digital data storage using DNA nanostructures and solid-state nanopores. _Nano Lett._ 19, 1210–1215 (2019). Article Google Scholar * Janasek, D., Franzke, J. & Manz, A.

Scaling and the design of miniaturized chemical-analysis systems. _Nature_ 442, 374 (2006). Article Google Scholar * Knowles, T. P. J. et al. Observation of spatial propagation of amyloid

assembly from single nuclei. _Proc. Natl Acad. Sci._ 108, 14746–14751 (2011). Article Google Scholar * Challa, P. K. et al. Real-time intrinsic fluorescence visualization and sizing of

proteins and protein complexes in microfluidic devices. _Anal. Chem._ 90, 3849–3855 (2018). PMID: 29451779. Article Google Scholar * Yates, E. V. et al. Latent analysis of unmodified

biomolecules and their complexes in solution with attomole detection sensitivity. _Nat. Chem._ 7, 802–809 (2015). Article Google Scholar * Bortolini, C. et al. Resolving protein mixtures

using microfluidic diffusional sizing combined with synchrotron radiation circular dichroism. _Lab. Chip_ 19, 50–58 (2019). Article Google Scholar * Herling, T. W. et al. A microfluidic

platform for real-time detection and quantification of protein-ligand interactions. _Biophys. J._ 110, 1957–1966 (2016). Article Google Scholar * Saar, K. L. et al. On-chip label-free

protein analysis with downstream electrodes for direct removal of electrolysis products. _Lab Chip_ 18, 162–170 (2018). Article Google Scholar * Saar, K. L., Müller, T., Charmet, J.,

Challa, P. K. & Knowles, T. P. J. Enhancing the resolution of micro free flow electrophoresis through spatially controlled sample injection. _Anal. Chem._ 90, 8998–9005 (2018). 8b01205

PMID: 29938505. Article Google Scholar * Bocquet, L. & Charlaix, E. Nanofluidics, from bulk to interfaces. _Chem. Soc. Rev._ 39, 1073–1095 (2010). Article Google Scholar * Marbach,

S., Dean, D. S. & Bocquet, L. Transport and dispersion across wiggling nanopores. _Nat. Phys._ 14, 1108–1113 (2018). Article Google Scholar * Jubin, L., Poggioli, A., Siria, A. &

Bocquet, L. Dramatic pressure-sensitive ion conduction in conical nanopores. _Proc. Natl Acad. Sci._ 115, 4063–4068 (2018). Article Google Scholar * Schoch, R. B., Han, J. & Renaud, P.

Transport phenomena in nanofluidics. _Rev. Mod. Phys._ 80, 839–883 (2008). Article Google Scholar * de la Escosura-Muñiz, A. & Merkoçi, A. Nanochannels for electrical biosensing.

_Trends Anal. Chem._ 79, 134–150 (2016). Article Google Scholar * Inglis, D. W., Goldys, E. M. & Calander, N. P. Simultaneous concentration and separation of proteins in a nanochannel.

_Angew. Chem. Int._ 50, 7546–7550 (2011). Article Google Scholar * Wunsch, B. H. et al. Nanoscale lateral displacement arrays for the separation of exosomes and colloids down to 20 nm.

_Nat. Nanotechnol._ 11, 936–940 (2016). Article Google Scholar * Siria, A., Bocquet, M. L. & Bocquet, L. New avenues for the large-scale harvesting of blue energy. _Nat. Rev. Chem._ 1,

p 6 (2017). * He, Y. et al. Electrokinetic analysis of energy harvest from natural salt gradients in nanochannels. _Sci. Rep._ 7, 1–15 (2017). Article Google Scholar * Kim, D. K., Duan,

C., Chen, Y. F. & Majumdar, A. Power generation from concentration gradient by reverse electrodialysis in ion-selective nanochannels. _Microfluid. Nanofluidics_ 9, 1215–1224 (2010).

Article Google Scholar * Yusko, E. C. et al. Controlling protein translocation through nanopores with bio-inspired fluid walls. _Nat. Nanotechnol._ 6, 253–260 (2011). Article Google

Scholar * Bruno, G. et al. Unexpected behaviors in molecular transport through size-controlled nanochannels down to the ultrananoscale. _Nat. Commun._ 9, 1–10 (2018). Article Google

Scholar * Del Campo, A. & Greiner, C. SU-8: A photoresist for high-aspect-ratio and 3D submicron lithography. _J. Micromech. Microeng._ 17, p 92 (2007). * Xia, Y. & Whitesides, G.

M. Soft lithography. _Annu. Rev. Mater. Sci._ 28, 153–184 (1998). 1111.6189v1. Article Google Scholar * Feng, R. & Farris, R. J. Influence of processing conditions on the thermal and

mechanical properties of SU8 negative photoresist coatings. _J. Micromech. Microeng._ 13, 80–88 (2003). Article Google Scholar * Park, S. H., Yang, D. Y. & Lee, K. S. Two-photon

stereolithography for realizing ultraprecise three-dimensional nano/microdevices. _Laser Photonics Rev._ 3, 1–11 (2009). Article Google Scholar * Lee, K. S., Kim, R. H., Yang, D. Y. &

Park, S. H. Advances in 3D nano/microfabrication using two-photon initiated polymerization. _Prog. Polym. Sci._ 33, 631–681 (2008). Article Google Scholar * Malinauskas, M., Farsari, M.,

Piskarskas, A. & Juodkazis, S. Ultrafast laser nanostructuring of photopolymers: a decade of advances. _Phys. Rep._ 533, 1–31 (2013). Article Google Scholar * Juodkazis, S., Mizeikis,

V., Seet, K. K., Miwa, M. & Misawa, H. Two-photon lithography of nanorods in SU-8 photoresist. _Nanotechnology_ 16, 846–849 (2005). Article Google Scholar * Thiel, M., Rill, M. S., Von

Freymann, G. & Wegener, M. Three-dimensional bi-chiral photonic crystals. _Adv. Mater._ 21, 4680–4682 (2009). Article Google Scholar * Richter, B. et al. Guiding cell attachment in 3D

microscaffolds selectively functionalized with two distinct adhesion proteins. _Adv. Mater._ 29 https://doi.org/10.1002/adma.201604342 (2017). Article Google Scholar * Rill, M. S. et al.

Gold helix photonic metamaterial as broadband circular polarizer. _Science_ 325, 1513–1515 (2009). Article Google Scholar * Marino, A. et al. A 3D real-scale, biomimetic, and biohybrid

model of the blood-brain barrier fabricated through two-photon lithography. _Small_ 14, 1–9 (2018). Google Scholar * Hengsbach, S. & Lantada, A. D. Rapid prototyping of multi-scale

biomedical microdevices by combining additive manufacturing technologies. _Biomed. Microdevices_ 16, 617–627 (2014). Article Google Scholar * Eschenbaum, C. et al. Hybrid lithography:

combining UV-exposure and two photon direct laser writing. _Opt. Express_ 21, 29921 (2013). Article Google Scholar * Lin, Y., Gao, C., Gritsenko, D., Zhou, R. & Xu, J. Soft lithography

based on photolithography and two-photon polymerization. _Microfluid. Nanofluid._ 22, 97 (2018). Article Google Scholar * Kovarik, M. L. & Jacobson, S. C. Nanofluidics in

lab-on-a-chip devices. _Anal. Chem._ 81, 7133–7140 (2009). Article Google Scholar * Dempsey, G. T., Vaughan, J. C., Chen, K. H., Bates, M. & Zhuang, X. Evaluation of fluorophores for

optimal performance in localization-based super-resolution imaging. _Nat. Methods_ 8, 1027–1040 (2011). NIHMS150003. Article Google Scholar * Rowlands, C. J., Ströhl, F., Ramirez, P. P.,

Scherer, K. M. & Kaminski, C. F. Flat-field super-resolution localization microscopy with a low-cost refractive beam-shaping element. _Sci. Rep._ 8, 1–8 (2018). Article Google Scholar

* Ovesný, M., Kˇrížek, P., Borkovec, J., Švindrych, Z. & Hagen, G. M. ThunderSTORM: a comprehensive ImageJ plug-in for PALM and STORM data analysis and super-resolution imaging.

_Bioinformatics_ 30, 2389–2390 (2014). Article Google Scholar * Ruggeri, F. et al. Single-molecule electrometry. _Nat. Nanotechnol._ 12, 488–495 (2017). Article Google Scholar * Boukany,

P. E. et al. Nanochannel electroporation delivers precise amounts of biomolecules into living cells. _Nat. Nanotechnol._ 6, 747–754 (2011). Article Google Scholar * Zhang, Y., Huang, Z.,

He, Y. & Miao, X. Enhancing the efficiency of energy harvesting from salt gradient with ion-selective nanochannel. _Nanotechnology_ https://doi.org/10.1088/1361-6528/ab0ed8 (2019).

Article Google Scholar * Wollhofen, R., Katzmann, J., Hrelescu, C., Jacak, J. & Klar, T. A. 120nm resolution and 55nm structure size in STED-lithography. _Opt. Express_ 21, 10831

(2013). Article Google Scholar * Challa, P. K., Kartanas, T., Charmet, J. & Knowles, T. P. J. Microfluidic devices fabricated using fast wafer-scale LED-lithography patterning.

_Biomicrofluidics_ 11, 014113 (2017). Article Google Scholar Download references ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This work was supported by the Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council [Grant

numbers EP/L015889/1 and EP/L027151/1], the European research Council, the Winton Program for the Physics of Sustainability and the Newman Foundation. The authors would also like to thank

the NanoDTC for additional funding and the Maxwell Community for scientific support. This project has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation program

under Grant agreement No. 674979-NANOTRANS. The work was partially funded by Horizon 2020 program through 766972-FET-OPEN-NANOPHLOW. U.F.K. acknowledges funding from an ERC Consolidator

Grant (DesignerPores 647144). AUTHOR INFORMATION Author notes * These authors contributed equally: Oliver Vanderpoorten, Quentin Peter, Pavan K. Challa AUTHORS AND AFFILIATIONS * Department

of Chemical Engineering and Biotechnology, University of Cambridge, Philippa Fawcett Drive, Cambridge, CB3 0AS, UK Oliver Vanderpoorten & Clemens F. Kaminski * Department of Chemistry,

University of Cambridge, Lensfield Road, Cambridge, CB2 1EW, UK Oliver Vanderpoorten, Quentin Peter, Pavan K. Challa & Tuomas P. J. Knowles * Cavendish Laboratory, Department of Physics,

University of Cambridge, J. J. Thomson Avenue, Cambridge, CB30HE, UK Oliver Vanderpoorten, Ulrich F. Keyser, Jeremy Baumberg & Tuomas P. J. Knowles Authors * Oliver Vanderpoorten View

author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Quentin Peter View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Pavan

K. Challa View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Ulrich F. Keyser View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google

Scholar * Jeremy Baumberg View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Clemens F. Kaminski View author publications You can also search for this

author inPubMed Google Scholar * Tuomas P. J. Knowles View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar CONTRIBUTIONS O.V. and P.C. were conducting the

experiments, were involved in the SEM and AFM imaging of calibration samples, master wafers, and PDMS stamps, as well as device fabrication and interpreted the data from SEM and AFM imaging

together with Q.P. O.V. imaged the nanochannel devices using TIRF microscopy and was improving the device fabrication procedure. P.C. was project initiator and main contributor to the

optical design and hardware considerations of the 2PL system. Q.P. developed open-source software in Python to control the 2PL setup and was involved in the automation of the process and its

optimization using all available actuators. All authors provided input into the paper. CORRESPONDING AUTHOR Correspondence to Tuomas P. J. Knowles. ETHICS DECLARATIONS CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest. SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION SINGLE_MOLECULE_RHOD6G_VIDEO SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION RIGHTS AND PERMISSIONS OPEN ACCESS This article

is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give

appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in

this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative

Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a

copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. Reprints and permissions ABOUT THIS ARTICLE CITE THIS ARTICLE Vanderpoorten, O., Peter, Q., Challa, P.K. _et al._

Scalable integration of nano-, and microfluidics with hybrid two-photon lithography. _Microsyst Nanoeng_ 5, 40 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41378-019-0080-3 Download citation * Received:

07 February 2019 * Revised: 26 May 2019 * Accepted: 25 June 2019 * Published: 09 September 2019 * DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41378-019-0080-3 SHARE THIS ARTICLE Anyone you share the

following link with will be able to read this content: Get shareable link Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article. Copy to clipboard Provided by the Springer

Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative