Outcomes up to age 36 months after congenital Zika virus infection—U.S. states

- Select a language for the TTS:

- UK English Female

- UK English Male

- US English Female

- US English Male

- Australian Female

- Australian Male

- Language selected: (auto detect) - EN

Play all audios:

To characterize neurodevelopmental abnormalities in children up to 36 months of age with congenital Zika virus exposure.

From the U.S. Zika Pregnancy and Infant Registry, a national surveillance system to monitor pregnancies with laboratory evidence of Zika virus infection, pregnancy outcomes and presence of

Zika associated birth defects (ZBD) were reported among infants with available information. Neurologic sequelae and developmental delay were reported among children with ≥1 follow-up exam

after 14 days of age or with ≥1 visit with development reported, respectively.

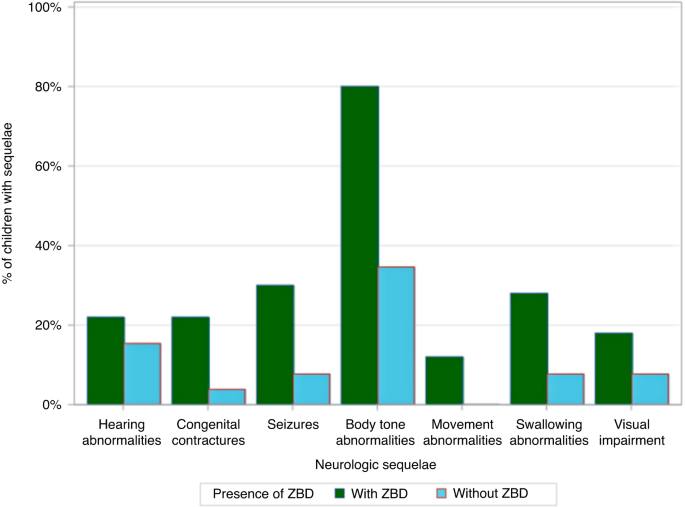

Among 2248 infants, 10.1% were born preterm, and 10.5% were small-for-gestational age. Overall, 122 (5.4%) had any ZBD; 91.8% of infants had brain abnormalities or microcephaly, 23.0% had

eye abnormalities, and 14.8% had both. Of 1881 children ≥1 follow-up exam reported, neurologic sequelae were more common among children with ZBD (44.6%) vs. without ZBD (1.5%). Of children

with ≥1 visit with development reported, 46.8% (51/109) of children with ZBD and 7.4% (129/1739) of children without ZBD had confirmed or possible developmental delay.

Understanding the prevalence of developmental delays and healthcare needs of children with congenital Zika virus exposure can inform health systems and planning to ensure services are

available for affected families.

We characterize pregnancy and infant outcomes and describe neurodevelopmental abnormalities up to 36 months of age by presence of Zika associated birth defects (ZBD).

Neurologic sequelae and developmental delays were common among children with ZBD.

Children with ZBD had increased frequency of neurologic sequelae and developmental delay compared to children without ZBD.

Longitudinal follow-up of infants with Zika virus exposure in utero is important to characterize neurodevelopmental delay not apparent in early infancy, but logistically challenging in

surveillance models.

Given the impact of Zika virus (ZIKV) infection on the developing fetal brain and eye, it is critical to examine neurodevelopment in infancy and early childhood as well as pregnancy outcomes

associated with congenital Zika virus exposure (CZVE).1 Uncertainty remains regarding frequency and spectrum of long-term neurodevelopmental outcomes for these children. In 2016, the

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and state, local, and territorial health departments established the U.S. Zika Pregnancy and Infant Registry (USZPIR) to monitor pregnancy,

infant, and childhood outcomes among pregnancies with laboratory evidence of confirmed or possible Zika virus infection.2,3 A previous USZPIR report evaluated outcomes among 1450 children

born in the U.S. territories and freely associated states, who were ≥1 year old, finding 6% had at least one Zika-associated birth defect (ZBD), 9% had at least one neurodevelopmental

abnormality, and 1% had both.4 However, pregnancy outcomes and neurodevelopmental data from the U.S. states and D.C. have not yet been reported from the USZPIR. Few cohort studies have

reported on the longer-term neurodevelopment of children with CZVE, with or without ZBD.5,6,7 Emerging evidence suggests that children with ZBD can exhibit neurodevelopmental delays not

detected until after their first year of life.8,9 However, among children without ZBD, information about the longer-term neurodevelopmental effects of CZVE is limited.1,10

A study in Colombia examined 77 infants with laboratory evidence of maternal ZIKV during pregnancy but no clinical signs of congenital Zika syndrome and normal prenatal neuroimaging.11 This

study, which reported on neurodevelopment as assessed by validated measures at around 6 and 13 months of age, showed neurodevelopmental scores falling further below the mean as the children

aged. Other studies have reported that children with prenatal ZIKV exposure can have normal findings on neurodevelopmental assessments in the first year of life but exhibit

neurodevelopmental delays in the second year of life.11 A concern for language delays has also been reported for children greater than12 months of age with a history of CZVE with and without

ZBD.5,6,7,12 Given the progressive nature of early child neurodevelopment and the possibility for delays to emerge beyond the first year of life, longitudinal surveillance is necessary.

Using the data from the USZPIR, we sought to expand on prior reports from this cohort by providing an updated estimate of adverse pregnancy outcomes, including not previously reported

findings for small-for-gestational age (SGA) and preterm birth (PTB), neurologic sequelae, and neurodevelopmental abnormalities among children up to 3 years of age.

This report includes pregnancies reported to the USZPIR by December 31, 2021, that were completed in the U.S. states and D.C. from December 1, 2015 to March 31, 2018, with laboratory

evidence of confirmed or possible maternal ZIKV and infants resulting from these pregnancies. Laboratory evidence of confirmed or possible recent ZIKV was defined as (1) recent ZIKV

infection detected by a ZIKV RNA nucleic acid amplification test (NAAT, e.g., reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction [RT-PCR]) on any maternal, placental, or fetal/infant specimen

or (2) detection of recent ZIKV or recent unspecified flavivirus infection by serologic tests on a maternal or infant specimen (i.e., either positive or equivocal ZIKV immunoglobulin M [IgM]

and ZIKV plaque reduction neutralization test [PRNT] titer ≥10, regardless of dengue virus PRNT value [if PRNT is conducted in the jurisdiction]; or negative ZIKV IgM, and positive or

equivocal dengue virus IgM, and ZIKV PRNT titer ≥10, regardless of dengue virus PRNT titer). Additional details on methodology have been published previously.3,13

Data from prenatal care, birth hospitalization and delivery, and early childhood outcomes up to 36 months of age when available, were abstracted from medical records. Follow-up information

included physical examinations, neurodevelopmental screenings, assessments and evaluations, neuroimaging, hearing screenings, audiological evaluations, and ophthalmology examinations.

Birth outcomes were classified as live birth, pregnancy loss