Outcomes 10-years after traumatic spinal cord injury in botswana - a long-term follow-up study

- Select a language for the TTS:

- UK English Female

- UK English Male

- US English Female

- US English Male

- Australian Female

- Australian Male

- Language selected: (auto detect) - EN

Play all audios:

ABSTRACT STUDY DESIGN Prospective follow-up study. OBJECTIVES To describe outcomes, survival, and attendance to routine follow-up visits 10 years post-SCI. SETTING The national

SCI-rehabilitation center in Botswana. METHODS All persons who were admitted with traumatic SCI during a 2-year period, 2011–2013, and survived up to 2 years post-injury were included. Data

were collected from the medical records from the follow-up assessment closest to 10 years post-SCI and included demographic and clinical characteristics, functional outcomes, and secondary

complications. Data regarding mortalities were received from relatives. Statistical comparisons were made, when possible, between those who attend follow-up assessment and those who did not,

and between those who survived up to 10 years post-SCI and those who died. RESULTS The follow-up rate was 76% (19/25) of known survivors. No statistically significant factors were found to

affect the follow-up rate. Secondary complications rates were for pressure ulcers and urinary tract infections 21%. Self-catheterisation and suprapubic catheter were the preferred methods to

manage neurogenic bladder dysfunction. Ten persons (26%) had deceased since 2nd follow-up assessment. The causes of death were probably SCI-related in more than half of the cases.

CONCLUSIONS This was a follow-up study at year 10 after acute TSCI in Botswana conducted at the national SCI-rehabilitation center. The study supports previous reports regarding the

importance of that having specialized SCI units and the need of structured follow-ups, a responsible person in charge of scheduling, and updated patient registers. We found high follow-up

rate, low rates of complications and of patients being lost to follow-up. SIMILAR CONTENT BEING VIEWED BY OTHERS MORTALITY AND SECONDARY COMPLICATIONS FOUR YEARS AFTER TRAUMATIC SPINAL CORD

INJURY IN CAPE TOWN, SOUTH AFRICA Article 04 September 2020 CAUSES AND LENGTH OF STAY OF READMISSION AMONG INDIVIDUALS WITH TRAUMATIC SPINAL CORD INJURY: A PROSPECTIVE OBSERVATIONAL COHORT

STUDY Article Open access 25 February 2023 BLADDER MANAGEMENT, SEVERITY OF INJURY AND PERIOD OF LATENCY: A DESCRIPTIVE STUDY ON 135 PATIENTS WITH SPINAL CORD INJURY AND BLADDER CANCER

Article 17 June 2021 BACKGROUND Living with spinal cord injury (SCI) imposes an increased vulnerability for preventable complication leading to increased suffering, and increased risk of

morbidity and premature death, especially in low-resource settings [1, 2]. The life expectancy for persons with SCI have improved greatly during the last decades in many industrialized

countries [1, 3,4,5,6], attributed to the development of specialized SCI-care and structured long-term follow-ups. To be managed at a specialized unit after SCI is beneficial both for the

patient and for the society’s economy [7]. Structured follow-ups are conducted as comprehensive interdisciplinary re-evaluation with the main aim to prevent complications and decrease

morbidity and mortality [8]. The first year’s follow-up assessments often focus on facilitating reintegration in communities and return-to-work, while in the long run the focus changes to

health maintenance, preventing the needs for re-admissions, and decreasing health care cost [8]. Specialized rehabilitation services and follow-up after discharge is often non-existing in

low-resourced settings [1, 5, 9]. Even when rehabilitation centers are available, routines for follow-ups are often lacking and mortality rates are substantially higher compared with more

resourceful settings [1]. Patients are often lost to follow-up and their status is unknown [10, 11]. Lack of patient registers and contact details, vast distances to specialized health care

clinics, and lack of transport are some reasons for not adequate follow-ups [9]. In many low-resource settings, preventable secondary complications such as sepsis due to pressure ulcers (PU)

[5, 12, 13] or recurrent urinary tract infections (UTI), and kidney and respiratory failure [9, 10] lead to high mortality rates in the SCI-population [3]. Several studies have also shown

an increased risk for cardiovascular disease in the SCI-population [1, 8, 9, 14] which constitute a common cause for mortality in high-income countries [6]. Botswana is a middle-income

country in southern Africa. Persons who sustained a traumatic SCI (TSCI) are transferred to the national referral hospital, Princess Marina Hospital (PMH) in the capital, and the

SCI-rehabilitation center. The center was established in 2010 through a 3-year partnership project between the Ministry of Health in Botswana and the Spinalis Foundation in Sweden, which was

partly funded by the Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency (Sida). Since 2013 the unit has been run by local professionals only and has provided in-patient services,

re-rehabilitation, out-patient clinics, and structured long-term follow-up. The follow-ups, conducted as interdisciplinary assessments, are an important part of the structure of the center

and are to be conducted at a minimum at 1rst, 2nd, 5th year post-injury and thereafter every fifth year. Often an early assessment is included due to the known high risk of developing

complications and premature death within one year after discharge [1, 3, 8]. Urine and blood samples, such as kidney and liver function, are routinely conducted during the follow-up visit.

Patients are scheduled by the responsible nurse and those living far away are offered lodging at the center. The up-take area of the national center is the whole country, i.e., some persons

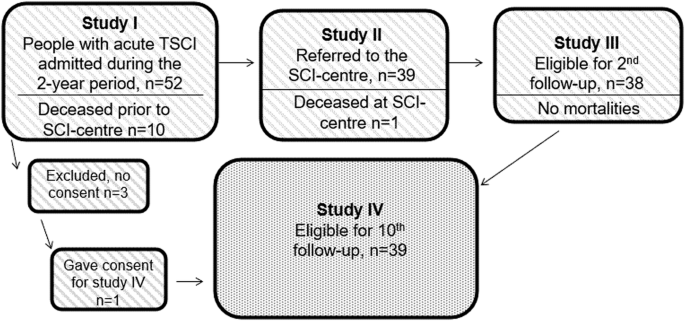

have to travel approximately 900 km one way. SUMMARY OF THE PREVIOUS STUDIES ON THIS PATIENT GROUP Three studies were previously conducted on the same cohort as in the current study, namely

all persons admitted with acute TSCI during a 2-years period. These studies followed three phases within the chain of SCI-care: acute admission, discharge, and follow-up two years

post-injury. The main results of the studies are presented below, for detailed information, articles are published in Spinal Cord. Acute admission [15]: 52 persons with acute SCI were

admitted; however, three persons did not consent therefore 49 participants were included, 71% male, age range was 4–81 years with 80% ⩽45 years, 59% had tetraplegia with 39% having a high

tetraplegia (C1–C4 level), mainly incomplete. Causes of injury were traffic related (68%), assault (16%), and falls (10%). Mortality prior to admission to the SCI-rehabilitation center was

20%, where all, but one, had tetraplegia, resulting in that 39 persons were admitted for rehabilitation. At discharge [16]: 38 persons were discharged after completed rehabilitation; one

person deceased prior to discharge after having completed rehabilitation. Median length of stay was 20 weeks with complete injuries and presence of PU being the factors that mostly prolonged

hospitalization. Clean intermittent catheterization (CIC) or suprapubic catheter (SPC) were the main methods for bladder management and digital ano-rectal stimulation for bowel management.

The most frequent complications during admission were PU, UTI, and pain. _At 2__nd_ follow-up [17]: follow-up rate was 71% (27 out of 38 persons attended follow-up, the remaining were

contacted by phone), with higher attendance among those with complete injuries and those with secondary complications. Age, gender, distance to the center, or education did not affect the

follow-up rate. CIC and SPC remained the preferred methods of bladder management. Despite high rates of PU and UTI, no deaths had occurred during the follow-up period resulting in 38 persons

survived to be included in the current study. RATIONAL Botswana, as well as a substantial part of Sub-Saharan Africa, is lacking reliable information on the long-term outcome and mortality

after SCI [9, 10, 18]. After initial establishment of a specialized SCI-center in Botswana, outcomes for persons with TSCI improved and mortality was decreased for up to two years

post-injury [17]. Complications were still prevalent, however, at a lower rate compared with before the SCI-center. Therefore, the aim of this study is to describe the long-term outcomes 10

years post-TSCI in Botswana after completing rehabilitation and attending to the follow-up assessments. Study goals: * 1. To evaluate the procedures of interdisciplinary follow-up

assessments at the SCI-center. * 2. To describe the medical status, consequences, and complications 10 years post-SCI for persons with TSCI in Botswana. * 3. To describe home situation,

functional outcomes, quality of life, and prevalence of work/studies 10 years post-SCI. * 4. To describe rate and causes of mortality for persons with TSCI after the 2nd yearly follow-up and

whether causes of death were SCI-related. MATERIALS AND METHODS This was a prospective follow-up study conducted at the national SCI-rehabilitation center in Botswana. The study population

includes all persons admitted to PMH with acute TSCI between February 1rst 2011 – January 31rst 2013 and who had survived up to two years post-SCI, i.e. the same cohort as in the three

previous studies, with an addition of one person who did not consent initially, but now gave verbal consent to participate, resulting in 39 participants who were included in the current

study (Fig. 1). DATA COLLECTION Data were collected from the medical files from the follow-up assessment as close as possible to the follow-up at 10 years post-SCI. Protocols used at the

assessments are mainly derived from the International Spinal Cord Society (ISCoS) [19] partly adapted to this setting. The following protocols were used: * 1. International standards for

neurological classification of SCI [20] * 2. ISCoS data sets: * a. CardiovascularMedical history regarding cardiac and circulatory problems. Questions added to the data set; pulmonary

diseases, tumors, tropical diseases, diabetes, HIV/AIDS. * b. Pain * c. Lower urinary tract function * d. Bowel function * e. Sexual function * f. Quality of life (QoL): Includes three

questions; ‘how satisfied are you’ with the following: ‘life as a whole’, ‘physical health’, and ‘psychological health, emotions and mood’. Ratings 0–10 completely dissatisfied–completely

satisfied. * 3. Sociodemographic protocol: Sociodemographic, work/study * 4. Functional Independence Measure (FIM) * 5. Pressure ulcer data: Previous and current pressure wounds. Data

regarding mortality rate, time, place, and causes of deaths have mainly been retrieved from the relatives since most persons deceased in their homes and no data regarding mortality were

available. An autopsy is only conducted at the request of the family when a person dies in their home. Data for deceased participants have been retrieved from their latest follow-up

assessment. ANALYSIS IBM SPSS statistics 28.0.0.0 (Armonk, NY, USA) were used for analyzing data. Categorical variables are presented as absolute numbers and proportions, and continuous

variables as mean and standard deviation (SD), and median and interquartile range (IQR) [21]. Non-parametric tests were used for comparing groups because of the small sample, Mann–Whitney

U-test for continuous variables and Fisher’s exact test for categorical variables. _P_-value were set to _P_ < 0.05. Time frame: the follow-ups at year 10 were to be conducted between

February 2021 and March 2023. Data collection from patient files, analysis, writing manuscript, and publishing was conducted in August 2023 – January 2024. RESULT Out of the 39 participants

who were included in this study, at least 25 survived up to 10 years, 10 participants had deceased, and four were lost to follow-up and their status is unknown. Demographic and clinical

characteristics are presented in Table 1. Of the 25 persons eligible for structured follow-up visits, 19 were scheduled and assessed which equal to a 76% follow-up rate. The time from date

of injury to the follow-up visits closest in time to 10 years post-SCI varied between 68–141 months, with a mean (SD) of 113.8 (22.4). Reasons for not attending follow-up included: not

wanting or feeling a need for follow-up (_n_ = 2), could not be scheduled due to incorrect contact information (_n_ = 2), living far away and having to take time off from work (_n_ = 1)

(living 900 km away from the clinic), and one participant did not have a relative who could drive him to the hospital. No demographic or clinical characteristic factors differed between

those who attended or did not attend follow-up. Cause of injury did not show any differences between groups but was included in the analysis due to persons with traffic related injuries are

being covered by the Motor vehicle accident-fund which facilitates provision of consumables and technical aids. The primary reason for persons being lost to follow-up is the lack of contact

information. Staff members have repeatedly made efforts to schedule all persons with TSCI, however their contacts have not been going through, and they have not contacted the unit

themselves. For participants who attended follow-up visit (_n_ = 19), 10 participants had an AIS A TSCI (Table 1). Five participants had improved AIS-score with 1–3 steps compared with

initial assessment. The prevalence of PU and UTI were 21%. Ten participants reported pain with musculoskeletal pain being most prevalent (Table 2). Eleven participants were single, however

only two lived alone. The majority lived together with family members such as parents or siblings. Five participants reported their house to be accessible to their needs, however several

lived in houses that were not adequately adapted. Ten participants were using manual wheelchairs and seven were partly or only ambulating. FIM and QoL were rated by all participants

attending follow-ups with total mean scores of 79 out of maximum 91 and 7.6–8.3/10 respectively (Table 1). We did not find significant differences for QoL compared with the 2nd year

follow-up. Regarding bladder and bowel management, seven participants reported normal function in both areas. Most of the participants used the same methods for management of neurologic

bladder as they did at the 2nd follow-up i.e. mainly CIC or SPC (Table 1). One child had progressed from CIC by assistant to self-catheterization. Digital ano-rectal stimulation was the

primary method to manage bowel dysfunction, however seven participants had gone back to performing it on their beds, whereas the rest used the toilet or a commode chair. Three participants

had colostomy, of whom one had got it due to non-SCI related issues (Table 1). All but one child rated sexual function which is presented in Table 3. Seven participants were working, 10 were

not working (one recently stopped due to medical reasons), and two were students (Table 1). Among the participants who deceased since the 2nd follow-up visit (_n_ = 10) seven had an AIS A

injury, four had tetraplegia, and the mean survival time from injury was 5.4 years. Causes of deaths were believed to be SCI-related for at least seven participants with possible causes

being sepsis due to PU, collapsed (possibly due to cardiovascular disease), and autonomic dysreflexia. At least two were none-related to SCI, and for one participant cause is unknown.

Further data are presented in Table 4 and derives from their last follow-up assessments, conducted 3–6 years after TSCI. Data were largely missing for four persons due to missing patient

files. DISCUSSION The present study was a follow-up study at year 10 post-SCI in Botswana, including the same participants who were included in three previously published studies [15,16,17].

Structured long-term follow-up is often a challenge in low-resource settings with high rates of patients being lost to follow-up [5, 11, 22]. Lack of transport is a common problem all over

the African region and distances are vast. Therefore, the follow-up rate of 76% and only four persons being lost to follow-up are positive findings. Factors facilitating the follow-up rate

is likely to include the existence of the SCI-unit, the structure of interdisciplinary follow-ups, an understanding among the staff that follow-up assessments are valuable, up-dated patient

register, and an allocated nurse being responsible for scheduling patients. However, follow-up frequency was inconsistent, with occasional gaps of time between scheduled visits. There are

several reasons for these gaps of time of which one is a lack of managing schedule slots due to a rotation system of staff in the public health care system. These rotations of staff have

resulted in only one responsible nurse that is still there out of the initial 10 nurses that were trained by the Swedish staff. Continuous training of new staff has been challenged by the

large number of rotations and lack of time. When the responsible nurse is not at work, scheduling patients, especially with short notice in the event of cancellation, has not been

prioritized and is not efficient. Additionally, the physiotherapy and occupational therapy staff has been severely reduced which is why, at times, the center is without therapists. Other

barriers are lack of transport which has also been reported from other settings [9, 11]. Transport can be provided by the local clinics when cars are available, however, it is often an

unreliable system due to uncertainty if the car will be available for the transport home again. Previously, out-reach programs, also recommended by Burns et al. [5], were in place with the

staff being able to assess persons with SCI in rural settings, but that alternative has become very limited and is not used today for the SCI-team. Finally, during the Covid pandemic, almost

no follow-up assessments were conducted as the hospital was one of Botswana’s primary Covid hospitals. For the 19 participants assessed, the medical status was in general satisfactory with

relatively low rates of secondary complications. The rate of complications has decreased compared with the 2nd follow-up [17] where 48% PU and 41% UTI were found. Madasa et al. [22] recently

reported 29% PU four years post-injury, however 40% were lost to follow-up making the numbers uncertain. Furthermore, Hossein et al. [23] reported 26% PU after approximately three years

post-injury, however over 75% of the wheelchair users reported problems with PU prior to the follow-up. They also address the challenges to prevent PU in the home environment, despite having

patient education in their program and provision of wheelchairs and cushions. We attribute the relatively good health among the participant who attended the follow-ups in Botswana to the

rehabilitation offered at the unit, including training and provision of appropriate technical aids but also patient and family education. This is in line with Illis et al. [7], who states

that having access to specialized SCI-units decreases complications such as PU and UTI. The low rates of complications might also be due to that persons with SCI with time learn prevention

strategies at a more robust level and how to care for their bodies in a more optimal way. Just as important we believe that the out-patient clinics at the SCI-center are easily accessible

and that persons living with SCI know where to turn for advice. Finally, there are active local peer groups and WhatsApp SCI-groups that together with family provide support for the persons

living with SCI. The living situations were similar to the 2nd follow-up, with the majority being singles however, only two participants lived by themselves. Living independently often

requires that you have and can drive an adapted car, which is costly and not an option for most persons with SCI in Botswana. Living in single households in Botswana is not as common as in

Sweden, for example, where over 50% are single households [24], however, even though exact numbers are hard to find, the general living situation in Botswana is a mean of 3.8 persons per

household [25]. Functional outcomes according to FIM-assessments and QoL showed high ratings, i.e. the participants who survived and were able to attend follow-ups maintained relatively good

functional skills and psychological health. Dixon et al. [26] found that QoL ratings were higher 10 years after injury as compared with 18 months, however due to our small population, the

non-significant statistical analysis is uncertain. Other studies have shown high rates of depression [3, 23] which is likely to affect many factors of life. Better psychological health can

have contributed to the decreased rates of morbidity, since it is well known that depression can affect PU in a negative direction [1, 23]. When it comes to the work situation, persons with

disabilities are often seen as another mouth to feed without being able to contribute to the family’s finances [5] and return-to-work is often hindered by inaccessibility in the society and

lack of transport [9], increasing the risk of poverty and pre-mature death [1, 3]. In this present study almost half of the participants were working or were students which is in line with a

recent review [27]. One participant had recently stopped working after he was laid off by the employer. In Botswana there are no laws protecting persons with disabilities in work related

issues, and people can be dismissed on medical grounds. Pre-mature mortality in general, is reported to be high in the southern part of Africa [2, 22]. In our study, the mortality rate was

26%, with the addition that four persons were lost to follow-up. This was somewhat higher than expected after having 100% survival from discharge to two years post-SCI [17] and might also

indicate increased awareness among persons with SCI in seeking attention from the unit when needed and that it takes time to learn how to adjust to the preventive strategies needed after

SCI. Considering the estimated high mortality rate before the establishment of the SCI-center, approximately 85% among wheelchair users within a year from discharge according to the local

doctor who has work with this patient group for many years, survival has greatly improved. Septicaemia due to PU is a common cause of mortality in low-resource settings and was also the main

cause of death in this study. For at least seven of the 10 participants who had deceased, causes of mortality were likely SCI-related, due to PU, autonomic dysreflexia, or collapse.

Identifying autonomic dysreflexia as the potential cause were done by the medical staff at the unit from the description from the relatives. Sweating, headache, and high blood pressure had

been present probably due to bladder problems. These outcomes strengthen the need for increased knowledge also at local clinics when persons with SCI live far away from SCI-clinics. The

medical staff identified that cardiovascular complications can be possible causes for the lethal collapses that occurred, due to the increased risk among the SCI-population [14]. All but two

participants deceased in their homes and no autopsies were conducted resulting in no causes of mortality being recorded in the hospital. Information of cause and time of death was provided

by the persons’ families who contacted the SCI-center staff and should therefore be viewed as more anecdotal. Øderud [3] describe a more robust method to gather information regarding causes

of death in areas where civil registration and death certification systems are weak. This more robust method is done as a verbal autopsy through structured interviews with the relatives or

other caregivers and is often the only way to establish causes of death in these kinds of settings [28]. At the SCI-center in Botswana, these interviews have not been used, but might be

implemented in the future to strengthen the reliability of mortality information. However, we still believe that it is appropriate to include the mortality data since they provide potential

causes of mortality in a middle-income setting. The unit has previously no structured documentation of mortality data however, the need for this has been clarified and documentation of

retrieved information regarding mortality will be initiated for future studies. STRENGTH AND WEAKNESSES A major strength of this study is that it has been conducted in the southern part of

Africa from where data is largely lacking. Persons with TSCI in Botswana are being largely followed-up and data are documented in patient files. For those who attended follow-up visits, data

were mainly complete. However, the weaknesses of the study include lack of data especially from those who did not attend follow-up visits or are lost to follow-up. Often the last recorded

data in their patient files were from their discharge notes, i.e. approximately 9–10 years old. Additionally, circumstances around fatalities are vague due to that accurate data were not

known or documented. Data for comparison were retrieved from their last follow-up visits, however medical files were lost for four patients and for those no data is available. The missing

data and the small sample results in limited and unreliable statistical comparisons. CONCLUSION This was a follow-up study at year 10 after acute TSCI in Botswana conducted at the national

SCI-rehabilitation center. The study supports previous reports regarding the importance of that having specialized SCI units for this patient group and the need of structured regular

follow-ups, a responsible person in charge of scheduling patients, and an updated patients register. In this study we found high follow-up rate, low rates of deadly complications, and low

numbers of patients being lost to follow-up. DATA AVAILABILITY Deidentified data are available from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request. REFERENCES * WHO/ISCoS. International

Perspectives on Spinal Cord Injury. 2013. https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/94190/9789241564663_eng.pdf?sequence=1. Accessed 17 Jan 2024. * WHO website on spinal cord injury. 2013.

https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/spinal-cord-injury. Accessed 17 Jan 2024. * Øderud T. Surviving spinal cord injury in low-income countries. Afr J Disabil. 2014;3:80.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Barman A, Shanmugasundaram D, Bhide R, Viswanathan A, Magimairaj HP, Nagarajan G, et al. Survival in Persons With Traumatic Spinal Cord

Injury Receiving Structured Follow-Up in South India. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2014;95:642–8. Article PubMed Google Scholar * Burns AS, O’Connell C. The challenge of spinal cord injury care

in the developing world. J Spinal Cord Med. 2012;35:1. Article Google Scholar * Ahoniemi E, Pohjolainen T, Kautiainen H. Survival after Spinal Cord Injury in Finland. J Rehabil Med.

2011;43:481–5. Article PubMed Google Scholar * Illis LS. The case for specialist units. Spinal Cord. 2004;42:443–6. Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Chhabra HS. ISCoS Textbook on

Comprehensive management of Spinal cord injuries. 1rst ed. Wolters Kluwer Pvt Ltd. New Delhi, India; 2015. p. 888. * Rathore FA. Spinal Cord Injuries in the Developing World. In: JH Stone, M

Blouin, editors. International Encyclopedia of Rehabilitation. 1rst ed. Center for International Rehabilitation Research Information and Exchange (CIRRIE); 2010. * Gosselin A, Coppotelli C.

A follow-up study of patients with spinal cord injury in Sierra Leone. Int Orthop. 2005;29:330–2. Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Nwadinigwe CU, Iloabuchi TC,

Nwabude IA. Traumatic spinal cord injuries (SCI): a study of 104 cases. Niger J Med. 2004;13:161–5. CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Hossain MS, Rahman MA, Herbert RD, Quadir MM, Bowden JL,

Harvey LA. Two-year survival following discharge from hospital after spinal cord injury in Bangladesh. Spinal Cord. 2016;54:132–6. Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Krause JS, Saunders

L. Health, Secondary Conditions, and Life Expectancy After Spinal Cord Injury. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2011;92:1770–5. Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Wahman K, Nash MS,

Lewis JE, Seiger Å, Levi R. Increased Cardiovascular Disease Risk in Swedish Persons with Paraplegia: The Stockholm Spinal Cord Injury Study. J Rehabil Med. 2010;42:489–92. Article PubMed

Google Scholar * Löfvenmark I, Norrbrink C, Nilsson Wikmar L, Hultling C, Chakandinakira S, Hasselberg M. Traumatic spinal cord injury in Botswana: characteristics, aetiology and mortality.

Spinal cord. 2015;53:150–4. Article PubMed Google Scholar * Löfvenmark I, Hasselberg M, Nilsson Wikmar L, Hultling C, Norrbrink C. Outcomes after acute traumatic spinal cord injury in

Botswana – from admission to discharge. Spinal Cord. 2017;55:208–12. Article PubMed Google Scholar * Löfvenmark I, Nilsson, Wikmar L, Hasselberg M, Norrbrink C, Hultling C. Outcomes 2

years after traumatic spinal cord injury in Botswana: a follow-up study. Spinal Cord. 2017;55:285–9. Article PubMed Google Scholar * Paulus-Mokgachane TMM, Visagie SJ, Mji G. Access to

primary care for persons with spinal cord injuries in the greater Gaborone area, Botswana. Afr J Disabil. 2019;8:539. Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * International Spinal

Cord Society (ISCoS). https://www.iscos.org.uk/page/Int-SCI-Data-Sets. Accessed on 17 Jan 2024. * Marino RJ, Barros T, Biering-Sörensen F, Burns SP, Donovan WH, Graves DE, et al.

International standards for neurological classification of spinal cord injury. J Spinal Cord Med. 2003;26:50–56. Article Google Scholar * DeVivo MJ, Biering-Sørensen F, New P, Chen Y.

Standardization of data analysis and reporting of results from the International Spinal Cord Injury Core Data Set. Spinal Cord. 2011;49:596–9. Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Madasa

V, Boggenpoel B, Phillips J, Joseph C. Mortality and secondary complications four years after traumatic spinal cord injury in Cape Town, South Africa. Spinal Cord Ser Cases. 2020;6:84.

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Hossain MS, Rahman MA, Bowden JL, Quadir MM, Herbert RD, Harvey LA. Psychological and socioeconomic status, complications and quality

of life in people with spinal cord injuries after discharge from hospital in Bangladesh: a cohort study. Spinal Cord. 2016;54:483–9. Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Eurostat. 2017.

https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/products-eurostat-news/-/ddn-20170905-1. Accessed on 2 Jan 2024. * Statistics Botswana. 2022. https://www.statsbots.org.bw/average-household-size. Accessed

17 Jan 2024. * Dixon R, Derrett S, Samaranayaka A, Harcombe H, Wyeth EH, Beaver C, et al. Life satisfaction 18 months and 10 years following spinal cord injury: results from a New Zealand

prospective cohort study. Qual Life Res. 2023;32:1015–30. Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Nowrouzi-Kia B, Nadesar N, Sun Y, Ott M, Sithamparanathan G, Thakkar P.

Prevalence and predictors of return to work following a spinal cord injury using a work disability prevention approach: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Trauma. 2022;24:14–23. Article

Google Scholar * Setel PW, Whiting DR, Hemed Y, Chandramohan D, Wolfson LJ, Alberti KG, et al. Validity of verbal autopsy procedures for determining cause of death in Tanzania. Tropical

Med Int Health. 2006;11:681–96. Article Google Scholar Download references ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS We thank Karolinska Institutet for dedicating travel funds to conduct data collection in

Botswana and to the Spinalis Foundation for their support. FUNDING Open access funding provided by Karolinska Institute. AUTHOR INFORMATION AUTHORS AND AFFILIATIONS * Karolinska Institutet,

Institution for neurobiology, care science and society, Stockholm, Sweden Inka Löfvenmark * Spinalis Foundation, Solna, Sweden Inka Löfvenmark * Spinalis Botswana SCI-rehabilitation Centre,

Gaborone, Botswana Wame Mogome & Kobamelo Sekakela Authors * Inka Löfvenmark View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Wame Mogome View

author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Kobamelo Sekakela View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar

CONTRIBUTIONS Protocol design: IL. Recruitment WM, KS. Data collection: All authors. Data analysis: IL. Manuscript draft: IL. Manuscript review: All authors. Approval of final manuscript:

All authors. CORRESPONDING AUTHOR Correspondence to Inka Löfvenmark. ETHICS DECLARATIONS COMPETING INTERESTS The authors declare no competing interests. ETHICAL APPROVAL The study was

approved by the Health Research and Development Division at the Ministry of Health in Botswana (ref no: HPRD 6/13/1 and HPRD 6/14/1) and the ethical board at Princess Marina Hospital (ref

no: PMH 2/11AII (46)). Prior to the study, informed consent was obtained from the participants. Methods used were performed in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations. ADDITIONAL

INFORMATION PUBLISHER’S NOTE Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. RIGHTS AND PERMISSIONS OPEN ACCESS This

article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as

you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party

material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s

Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. Reprints and permissions ABOUT THIS ARTICLE CITE THIS ARTICLE Löfvenmark, I., Mogome, W. & Sekakela, K.

Outcomes 10-years after traumatic spinal cord injury in Botswana - a long-term follow-up study. _Spinal Cord Ser Cases_ 10, 57 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41394-024-00671-0 Download

citation * Received: 03 April 2024 * Revised: 26 July 2024 * Accepted: 31 July 2024 * Published: 07 August 2024 * DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41394-024-00671-0 SHARE THIS ARTICLE Anyone

you share the following link with will be able to read this content: Get shareable link Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article. Copy to clipboard Provided by the

Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative