The psychiatric phenotypes of 1q21 distal deletion and duplication

- Select a language for the TTS:

- UK English Female

- UK English Male

- US English Female

- US English Male

- Australian Female

- Australian Male

- Language selected: (auto detect) - EN

Play all audios:

Copy number variants are amongst the most highly penetrant risk factors for psychopathology and neurodevelopmental deficits, but little information about the detailed clinical phenotype

associated with particular variants is available. We present the largest study of the microdeletion and -duplication at the distal 1q21 locus, which has been associated with schizophrenia

and intellectual disability, in order to investigate the range of psychiatric phenotypes. Clinical and cognitive data from 68 deletion and 55 duplication carriers were analysed with logistic

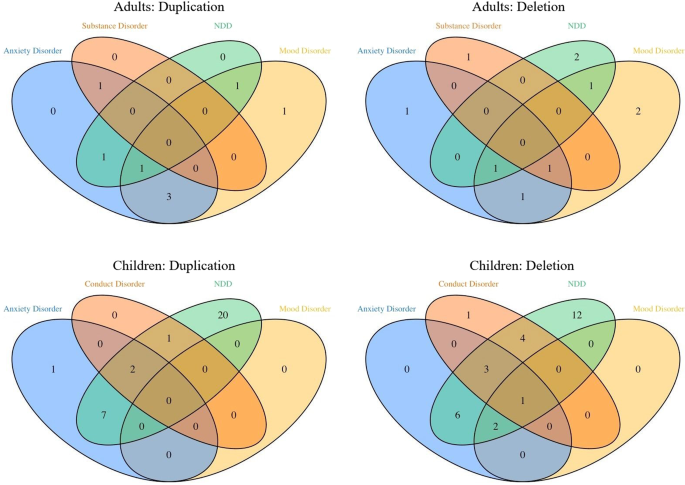

regression analysis to compare frequencies of mental disorders between carrier groups and controls, and linear mixed models to compare quantitative phenotypes. Both children and adults with

copy number variants at 1q21 had high frequencies of psychopathology. In the children, neurodevelopmental disorders were most prominent (56% for deletion, 68% for duplication carriers).

Adults had increased prevalence of mood (35% for deletion [OR = 6.6 (95% CI: 1.4–40.1)], 55% for duplication carriers [8.3 (1.4–55.5)]) and anxiety disorders (24% [1.8 (0.4–8.4)] and 55%

[10.0 (1.9–71.2)]). The adult group, which included mainly genetically affected parents of probands, had an IQ in the normal range. These results confirm high prevalence of

neurodevelopmental disorders associated with CNVs at 1q21 but also reveal high prevalence of mood and anxiety disorders in a high-functioning adult group with these CNVs. Because carriers of

neurodevelopmental CNVs who show relevant psychopathology but no major cognitive impairment are not currently routinely receiving clinical genetic services widening of genetic testing in

psychiatry may be considered.

The microdeletion and the microduplication at 1q21 (chr1: 146.57–147.39; GRCh37/hg19) are enriched in patients with schizophrenia (OR estimate for the deletion: 5.2; for the duplication:

2.9)1 and in patients with intellectual disabilities (ID)/developmental delay (DD) and autism spectrum disorder (ASD) (OR estimate for the deletion: 35; for the duplication: 18)2,3. The

estimates for the population frequency of the microdeletion and -duplication at this locus derived from UK Biobank are 0.027% and 0.044%, respectively4 although this may underestimate the

true frequency in the population because more severely affected carriers are likely to be underrepresented in a middle-aged research cohort.

The clinical phenotype of 1q21 deletion5,6 and duplication6 was originally established in clinical cohorts with intellectual disability, autism or congenital anomalies.

A systematic review of 22 studies containing data from 59 children and 48 adults with the 1q21.1 duplication7 reported high frequencies of neurodevelopmental problems including 50.8% for

DD/ID, 35.6% for autism or autistic features and 8.5% for seizures. In 2015, the Simons VIP Consortium published a comparison of 19 deletion carriers and 19 duplication carriers with

familial noncarrier controls8. Amongst deletion carriers, the most prevalent neuropsychiatric features were mood and anxiety disorders (26%) and seizures (18%), whereas the predominant

neuropsychiatric disorders in duplication carriers were ASD (41%) and ADHD (29%). A major limitation of the extant literature is that most studies have had small sample sizes and few reports

have included detailed psychiatric phenotyping, and there is very little detailed clinical data from adults. In the present multi-centre study, we tripled the sample size compared to the

Bernier et al.8 study (123 compared to 38 CNV carriers, also included in the present study). The aim of the current study was to analyse psychopathology in the largest international cohort

so far assembled that comprises carriers of the reciprocal microdeletion and –duplication at 1q21 across children and adults. We specifically wanted to ascertain whether mirror

phenotypes—similar to the established dose effect on head size6—also occur in the psychological domain and whether—and what type of—psychopathology was prevalent in an adult group largely

composed of family carriers and thus not affected by the ascertainment bias of clinical samples.

Participants were recruited by three research groups/consortia: the Simons Variation in Individuals Project (VIP) consortium (n = 51); the CNV Research Group, Lausanne University Hospital,

Lausanne, Switzerland (n = 12); and the Neuroscience and Mental Health Research Institute, Cardiff University, UK (n = 60). Unaffected family members were recruited as control participants

(Simons VIP: n = 51; Lausanne: n = 10; Cardiff: n = 9).

Participants assessed in Cardiff were recruited by three projects; children by the ‘Experiences of CHildren with cOpy number Variants’ (ECHO) and ‘Intellectual Disability and Mental Health:

Assessing the Genomic Impact on Neurodevelopment’ (IMAGINE-ID, http://imagine-id.org/)9 studies, and adults through the ‘Defining Endophenotypes From Integrated Neurosciences’ (DEFINE)

study. Participants were given details of our study following a diagnosis of a 1q21.1 CNV at one of the UK National Health Service genetics clinics. The study was also advertised on support

websites and social media groups for carriers of 1q21.1 CNVs. Adult participants were screened for the capacity to consent using a telephone-based protocol. If they were deemed to lack

capacity, a personal consultee was contacted. All participants, or their personal consultee, provided informed written consent. For participants under the age of 16, parent/guardian consent

and participant assent were obtained. For 16–18-year-old participants consent was obtained from participant and parent/guardian. All interviews were taped and decisions on psychiatric

symptoms and diagnosis were made during consensus meetings led by a psychiatrist. The South-East Wales Research Ethics Committee approved the recruitment and assessment protocols used in

this study (14/WA/0035). For the IMAGINE-ID study, protocols were approved by the NHS London Queen Square research ethics committee (14/LO/1069).

Participants in the Simons VIP consortium were ascertained clinically and recruited online and through clinical laboratory referrals in the United States. Data were collected at three

participating U.S. sites. Further details on the methods are available in Simons VIP, 201210. Participants with known additional clinically recognized CNVs were excluded. Assessments were

standardized across sites through ongoing training and inter-rater reliability checks. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Boards at Columbia University (AAAF3927), Geisinger

Health System (2011-0320), Children’s Hospital of Boston (12-009720), Baylor College of Medicine (H-27549) and the University of Washington (39149), and all participants 18 or older or the

participant’s designated legal guardian provided written informed consent (and children under 18 were assented, when appropriate, based upon mental capacity).

Participants from the CNV Research Group (Lausanne) were taking part in a larger research project on CNVs at the 1q21.1 locus. Proband carriers were referred to the study by clinical

geneticists. The study was reviewed and approved by the local ethics committee (CER-VD; PB_2016-02137) and written informed consent was obtained from participants or legal representatives

before investigation. Participants were assessed at the Lausanne University Hospital, Switzerland.

Data from 123 participants, comprising 68 deletion and 55 duplication carriers, were analysed for this study and compared with data from 70 familial controls. Participants were grouped and

analysed according to carrier status (deletion, duplication and control) and age group (child