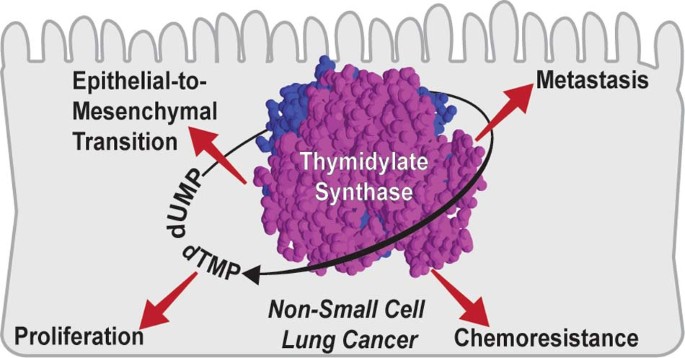

Thymidylate synthase drives the phenotypes of epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition in non-small cell lung cancer

- Select a language for the TTS:

- UK English Female

- UK English Male

- US English Female

- US English Male

- Australian Female

- Australian Male

- Language selected: (auto detect) - EN

Play all audios:

ABSTRACT BACKGROUND Epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT) enhances motility, stemness, chemoresistance and metastasis. Little is known about how various pathways coordinate to elicit

EMT’s different functional aspects in non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC). Thymidylate synthase (TS) has been previously correlated with EMT transcription factor ZEB1 in NSCLC and imparts

resistance against anti-folate chemotherapy. In this study, we establish a functional correlation between TS, EMT, chemotherapy and metastasis and propose a network for TS mediated EMT.

METHODS Published datasets were analysed to evaluate the significance of TS in NSCLC fitness and prognosis. Promoter reporter assay was used to sort NSCLC cell lines in TSHIGH and TSLOW.

Metastasis was assayed in a syngeneic mouse model. RESULTS TS levels were prognostic and predicted chemotherapy response. Cell lines with higher TS promoter activity were more

mesenchymal-like. RNA-seq identified EMT as one of the most differentially regulated pathways in connection to TS expression. EMT transcription factors HOXC6 and HMGA2 were identified as

upstream regulator of TS, and AXL, SPARC and FOSL1 as downstream effectors. TS knock-down reduced the metastatic colonisation in vivo. CONCLUSION These results establish TS as a theranostic

NSCLC marker integrating survival, chemo-resistance and EMT, and identifies a regulatory network that could be targeted in EMT-driven NSCLC. SIMILAR CONTENT BEING VIEWED BY OTHERS TGF-Β

INDUCED EMT AND STEMNESS CHARACTERISTICS ARE ASSOCIATED WITH EPIGENETIC REGULATION IN LUNG CANCER Article Open access 30 June 2020 TFAP2A DRIVES NON-SMALL CELL LUNG CANCER (NSCLC)

PROGRESSION AND RESISTANCE TO TARGETED THERAPY BY FACILITATING THE ESR2-MEDIATED MAPK PATHWAY Article Open access 18 December 2024 PRPC CONTROLS EPITHELIAL-TO-MESENCHYMAL TRANSITION IN

EGFR-MUTATED NSCLC: IMPLICATIONS FOR TKI RESISTANCE AND PATIENT FOLLOW-UP Article Open access 15 August 2024 BACKGROUND Epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT) is an embryonic process

hijacked by epithelial-like carcinoma cells to gain mesenchymal-like phenotype. Oncogenic EMT is a gamut of functional changes, such as enhanced motility, invasiveness, stemness,

aggressiveness and chemoresistance, and is a key determinant of metastasis. EMT is a complex cascade of molecular events engendered by master EMT transcription factors (EMT-TFs, ZEB1/2,

SNAI1/2 and TWIST) in response to extracellular cues including cytokines and hypoxia.1,2 EMT-TFs activate multiple molecular pathways that ultimately leads to alteration in cytoskeleton and

cell-adhesion proteins.3 EMT is a key early event in NSCLC biology and steers epithelial-like cells towards stemness, chemoresistance and metastatic dissemination.4,5 It is engineered

through coordination of divergent molecular pathways,6 and presumably orchestrated by different EMT-TFs at different progression time points.7,8,9 How these pathways connect to each other

and affect different modalities of EMT is still largely unexplored. Thymidylate synthase (TS) is a de novo pyrimidine biosynthesis enzyme that catalyses the conversion of deoxyuridine

monophosphate to thymidine monophosphate, essential for DNA synthesis and cell proliferation. It is targeted by chemotherapeutic drugs, like pemetrexed, in NSCLC, and has been widely studied

as a chemoresistance marker.10 Our lab recently showed a correlation between TS expression and EMT markers in NCI-60 panel of cancer cell lines originating from different tissues11 and

established its role in maintaining the de-differentiated mesenchymal-like state of triple-negative breast cancer.12 In this study we present evidence that TS is not a mere proliferation

marker in NSCLC, but also has a direct role in driving EMT phenotypes, with several biological and clinical implications. METHODS CELL LINES A549 (NCI), SK-MES-1 and Calu-1 (both ATCC) were

cultured in RMPI-1640, supplemented with 10% FBS, 1%Pen/Strep and 1%l-Glutamine (all from Sigma). NIC-H23 cells were cultured in RMPI-1640, supplemented with 10% FBS, 1%Pen/Strep,

1%l-Glutamine and 1 mM sodium pyruvate (Sigma). LL/2, Ladi 3.1 and Ladi 2.1 cells were cultured in DMEM (Sigma) supplemented with 10% FBS, 1%Pen/Strep and 1%l-Glutamine. Human cells were

STR-profiled, used between passages 3 and 15, examined for mycoplasma and maintained in Plasmocin (Invivogen) to prevent contamination. LENTIVIRAL TRANSDUCTION Plasmids for TS knock down

(TRCN0000456666 for human cell lines and TRCN0000317583 for murine cell lines) are from Sigma. Scrambled pLKO.1 (referred to as pLKO) was used as control. Plasmids from _TYMS_-promoter

reporter (HPRM33357-LvPM02), GAPDH promoter reporter (HPRM39787-LvPM02), TS expression vector (Ex-T0406-LV105b) and control vector (Ex-Neg-LV105b) are from GeneCopoeia. For production of

lentiviral particles, 293T cells were transfected with 8 µg knock-down/expression vectors and 2 µg of pMDL, pVsVg and pRevRes in complex with 24 µg PEI (Polysciences). After 48 h,

supernatant was collected, centrifuged and filtered. For transduction, 105 cells were seeded in a six-well plate and infected in presence of 8 μg/ml polybrene (Sigma). Selection was done

with 3 μg/ml puromycin (Sigma) and cells were maintained in 1 µg/ml puromycin. RNA SEQUENCING Total RNA was extracted using miRNeasy kit (Qiagen) following the manufacturer’s instructions.

RNA-Seq libraries were constructed using the TruSeq sample Prep Kit V2 (Illumina). Briefly, 1 μg of purified RNA was poly-A selected and fragmented with fragmentation enzyme. After first and

second strand synthesis from a template of poly-A selected/fragmented RNA, other procedures from end-repair to PCR amplification were done according to library construction steps. Libraries

were purified and validated for appropriate size on a 2100 Bioanalyzer High Sensitivity DNA chip (Agilent Technologies). The DNA library was quantified using Qubit and normalised to 4 nM

before pooling. Libraries were pooled in an equimolar fashion and diluted to 10 pM. Library pools were clustered and run on Nextseq500 platform with paired-end reads of 75 bases, according

to the manufacturer’s recommended protocol (Illumina). Raw reads passing the Illumina RTA quality filter were pre-processed using FASTQC for sequencing base quality control. Sequence reads

were mapped to UCSC human genome build using TopHat and differential gene expression determined using Cufflinks 2.1.1 and Cuffdiff2.1.1 as implemented in BaseSpace. The sequencing data has

been submitted GEO dataset and could be accessed with GSE148589 accession number. QUANTITATIVE REAL-TIME PCR Total RNA was extracted using miRNeasy kit (Qiagen) and 50 ng was converted to

cDNA using Tetro cDNA synthesis kit (Bioline) with random hexamers. GAPDH was used as an internal control. TaqMan probes (Thermo-Fisher) were used for quantification in Applied Biosystems

7300. Fold change was calculated using the ΔΔCt method. GENE SET ENRICHMENT ANALYSIS Gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA), for computing overlap, on the differentially expressed genes upon TS

knockdown was performed with the gene set collections in the Molecular Signatures Database v6.1 software. For EMT gene set enrichment analysis in the patient data, normalised gene

expression values were downloaded from GEO database (GSE101929) and cbioportal platform for TCGA profile (LUAD, PanCaner). For calculation of TS Knockdown (KD) score, first, _z_ scores of

the down- and up-regulated genes upon TS knockdown were calculated. Then, the sum of z scores of downregulated genes was subtracted from the sum of z scores of upregulated genes and KD

scores were obtained for each patient. Patients were grouped for the analysis based on either the median value of TYMS gene expression or KD score. SURVIVAL ANALYSIS Normalised gene

expression profiles of lung cancer samples were downloaded from GEO (GSE50081, GSE72094, GSE30219) and mRNA expression values as Z-scores were obtained for TCGA profiles (LUAD and LUSC) from

cbioportal platform. Thirty-five samples from completely resected NSCLC patients were collected from the files of San Luigi Hospital, Orbassano, Turin, Italy. None of the patients received

either neo-adjuvant chemotherapy or radiation therapy and all received adjuvant cisplatin and pemetrexed. All cases were reviewed and classified using anonymised samples. Clinical samples

were stratified as TYMS-low and TYMS-high based on the median value of gene expression as cut-off. Kaplan–Meier estimate was used to generate survival curves and significance between the two

groups were analysed using log-rank test in R software. Survival graphs from the KM Plotter database was generated based on TYMS expression by using the auto select best cut-off option. TS

KD score for survival curve was calculated as described in the previous section. WESTERN BLOT ANALYSIS Cells were lysed in RIPA buffer and quantified using Pierce BCA kit (Thermo-Fisher).

Proteins lysates (10–20 μg) were resolved on 10% SDS–PAGE gels and transferred to PVDF membrane (Thermo-Fisher). Membranes were blocked in 5% Milk (BioRad) in 1XTBS-T and incubated overnight

in primary antibodies diluted in 5% milk at 4 °C. anti-TS (EPR4545) and -SPARC (SP205) antibodies were purchased from Abcam; anti-E- Cadherin (4A2), -Vimentin (D21H3), -AXL (C89E7), -FOSL1

(D80B4) and -β-Actin (8H10D10) were purchased from Cell Signaling. After incubation with secondary antibodies (Southern Biotech), the detection was performed using ECL (Thermo-Fisher) and

developed on X-Ray film (Thermo-Fisher) using a chemiluminescence imager, AGFA CP100. PROLIFERATION ASSAY For proliferation assay cells were seeded in 96-well plates in low density (5–20%

initial confluency). Plates were loaded in IncuCyte-Zoom (Essen Bioscience) and scanned every 2–4 h. For each scan, phase contrast image was acquired from every well and was analysed by

IncuCyte Zoom software. IN VITRO DRUG TREATMENT Pemetrexed was purchased from Sigma. For in vitro treatment cells were plated in a 96-well plate (4000 cells/well) and incubated overnight.

For cytotoxicity death assay, 2000X Cytotox Green Reagent (Essen Bioscience) was diluted in RPMI and working dilutions of pemetrexed was prepared in Cytotox Green supplemented media. After

treatment, plate was loaded in Incycuyte Zoom and images were acquired in real-time for phase to quantify growth. Activity of Cytotox reagent was simultaneously acquired at the green channel

to quantify death. Incycuyte Zoom software was used for the analysis and data export. MIGRATION ASSAY For migration assay cells were plated in 96-well plates so that they reach 90%

confluency overnight. Cells were wounded using WoundMaker (Essen Biosciences) as per the instruction from the manufacturer. Plates were loaded in IncuCyte Zoom and were automatically scanned

for programmed time interval. For each scan, wound width was recorded by the software and the proliferation inside the wound was normalised to the proliferation outside the wound, giving

relative wound density for each time point. TUMOURSPHERE CULTURE In all, 40,000 cells were seeded in triplicates in ultra-low attachment six-well plates (Corning) in complete Mammocult

medium (Stem Cell Technologies), prepared according to the manufacturer’s instruction. After formation, spheres were counted by spinning at 300 g for 5 min and suspending in PBS (Lonza).

SIRNA TRANSFECTION Reverse transfection was done with Lipofectamine RNAiMAX Transfection Reagent (Thermo). 50 nM siRNA were mixed with 1.5 µl transfection reagent in 200 µl Opti-MEM (Thermo)

and incubated for 15 min. After incubation transfection complex was added to the surface of a 12-well plates and 105 cells, suspended in 800 µl, were added. Cells were incubated at 37 °C,

5%CO2. Cells were lysed for western blot after 72 h. IN VIVO EXPERIMENTS C57BL/6 strain were used as experimental model to study effect of Ts-depletion in syngeneic LL/2 cells to prevent

immune rejection.13 Mice were anaesthetised using isoflurane and euthanised by cervical dislocation. For subcutaneous injections, 1 × 106 cells resuspended in 50 µl 0.9% NaCl were mixed with

Matrigel (Corning) in a ratio 1:1 (v:v). Cells were injected in right flanks of 10–15-weeks-old female C57BL/6, with eight mice per group. Calliper measurements were taken every 4th day and

tumour volume was calculated using the formula (Length × Width2 × π)/6. For tail-vein metastasis assay, 5 × 105 LL/2 pLKO and shTs cells were resuspended in 100 µl PBS and injected in the

tail vein of female C57BL/6, with 10 mice per group. Lung metastases were monitored by bioluminescence imaging (BLI) 4 weeks after injection. Anesthetised mice were intraperitoneally

injected with 150 mg/kg D-luciferin (Kayman Chemicals). Bioluminescence images were acquired with Lumina III in vivo Imaging System (IVIS, Perkin Elmer). For all the mice exposure time was

maintained at 180 s. Raw IVIS images were analysed with Living Image software and the metastasis was represented as radiance. STATISTICAL ANALYSIS Statistical tests were performed with the

GraphPad software v.7 comparing groups of different conditions with replicates. In all tests, the statistical significance was set at _p_ ≤ 0.05. RESULTS TS IS AN ESSENTIAL NSCLC GENE WITH

PROGNOSTIC/PREDICTIVE POWER AND CORRELATES WITH EMT SIGNATURES We evaluated different clinical aspects of TS in NSCLC and assayed its correlation with EMT. As a rate-limiting de novo

pyrimidine biosynthesis enzyme, _TYMS_ (gene coding TS) has been proposed as an essential gene, but so far, no functional data have been shown in NSCLC. To evaluate dependency of NSCLC on

TS, a dataset generated from a genome-wide CRISPR/Cas9 screen of 18,009 genes in 324 cancer cell lines was exploited.14 Based on a gene fitness score that defined how strongly a cancer is

dependent on a gene for survival and growth, a priority score was generated to identify the most promising drug targets. Among all the pan-cancer fitness genes identified, TS ranked 30th

(top 1%, Fig. 1a, see Supplementary Table 1 for the top 50 genes). In NSCLC subsets, it ranked 2nd and 19th in squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) and adenocarcinoma (ADC), respectively (Fig. 1b),

indicating that NSCLC strongly depend on TS for sustained growth. TS was also found to be 5th among the pan-cancer priority targets identified (Supplementary Fig. 1A). TS was the only

target of pemetrexed that exclusively appeared as significant in all the three lists (Supplementary Fig. 1A–C). In concordance, TS expression has been consistently found increased in NSCLC

compared to adjacent normal tissues15 and correlated with poor prognosis in different expression datasets analysed (Fig. 1c, d). TS is targeted by the anti-folate drug pemetrexed, and its

overexpression has been proposed to determine chemoresistance.16 For in vitro validation, we established shRNA-mediated TS knockdown in two NSCLC cell lines and observed a significant

increase in pemetrexed sensitivity (Fig. 1e, f). To test if in vitro evidence were also reflected in the outcome of chemotherapy-treated patients, we retrospectively analysed a small

case-series of NSCLC patients treated with pemetrexed-based chemotherapy and found that higher TS gene expression significantly associated with worse prognosis (Fig. 1g). These results

emphasise the importance of TS as a prognostic and predictive marker, in line with previous literature.10 However, chemoresistance is also an important hallmark of EMT, and recent pivotal

findings from our lab associated TS expression with EMT markers in cancers from different origins and suggested a potential direct role.11 To test this in NSCLC, we analysed cells belonging

to the CCLE dataset and found that lung cancer cell lines with high TS expression have enrichment in EMT signature genes (Supplementary Fig. 1F, G). When further categorised as epithelial or

mesenchymal based on ratio of Vimentin (_VIM_) and E-Cadherin (_CDH1_) expression,17 (Supplementary Fig. 1H) mesenchymal-like cells expressed higher TS compared to epithelial-like (Fig.

1h). To further demonstrate its clinical significance, we investigated multiple datasets and found that patients with higher TS expression were significantly enriched for hallmark EMT genes

(Fig. 1i, j and Supplementary Fig. 1I, J). These results indicate that TS is not only an essential proliferation gene with a strong prognostic and predictive role, but also has a potential

power in EMT in NSCLC. ENDOGENOUS TS LEVEL IS AN IMPORTANT DETERMINANT OF EMT PHENOTYPE TS expression has been shown to be highly varied in clinical samples stained for

immunohistochemistry15,18 and bioinformatic analysis revealed that, within a tumour, individual cells can have extremely diversified TS expression (Supplementary Fig. 2A, B). When mapped to

a published gene signature, individual cells with higher TS expression within a tumour showed a significant enrichment of EMT (Supplementary Fig. 2C). Hence, we postulated that intrinsic

level of TS could be a strong determinant of EMT. To functionally validate the hypothesis, Calu-1 (a SCC cell line) was stably transduced with a promoter reporter construct19 that expressed

mCherry fluorescent protein transcribed from _TYMS_ promoter (Fig. 2a). After puromycin selection, cells were FACS-sorted for highest and lowest red fluorescence (indicated further as TSHIGH

and TSLOW, Fig. 2b). TSLOW cells proliferated slower (Fig. 2c) and showed a distinct epithelial phenotype, whereas TSHIGH resembled a mesenchymal-like morphology (Fig. 2d). To confirm

differential EMT status at molecular level, expression of E-CAD and VIM, markers for epithelial-like and mesenchymal-like cells respectively, was quantified. At mRNA level, even with a

minimal difference in TS expression, there was a striking difference between the expression of _CDH1_ (gene coding E-CAD) and _VIM_ (Fig. 2e). TSLOW cells also expressed more E-CAD and

lesser VIM compared to TSHIGH cells at protein level (Fig. 2f), backed up by E-CAD changes observed in Calu-1 cells with knockdown and overexpression of TS (Supplementary Fig. 2D). Also,

with the knockdown of TS, there was proliferation loss in the cells (Supplementary Fig. 2E) as observed with the cells after sorting. When assayed in proliferation-normalised wound migration

assay, TSLOW cells migrated slower than TSHIGH cells (Fig. 2g, h). As a control for the promoter reporter assay, Calu-1 cells were sorted for GAPDH promoter activity and no difference in

EMT markers and migration was observed in GAPDHHIGH and GAPDHLOW cells (Fig. 2f–h). TSLOW cells also had reduced self-renewal capacity, quantified as the number of tumourspheres formed in a

low-adherence culture (Fig. 2i). Further validation came from A549, that we had previously characterised to have lost stem cell phenotype after TS knockdown.11 When sorted in TSHIGH and

TSLOW cells (Supplementary Fig. 2F), A549 cells, that exist in partial EMT state,20 recapitulated the EMT phenotypes observed in Calu-1 (Fig. 2j, k), although change in the self-renewal

capacity was not observed (Supplementary Fig. 2G). We further independently validated TS-mediated EMT by knocking down TS in NSCLC cell lines SK-MES-1 (SCC cell line) and NCI-H23 (ADC cell

line), where TS depletion led to upregulation of E-CAD and downregulation of VIM in SK-MES-1 (Supplementary Fig. 2H) and downregulation of VIM and ZEB1 (mesenchymal marker) in NCI-H23

(Supplementary Fig. 2I). Interestingly, a rapid reversion of EMT phenotype was observed in the sorted Calu-1 cells, concomitant with the normalisation of _TYMS_ promoter activity

(Supplementary Fig. 2J). This was more evident in functionally distinct A549 cells, where the sorted cells showed higher TS levels in TSHIGH a day after sorting, followed by a complete

normalisation of TS and EMT markers after few passages (Supplementary Fig. 2K). Therefore, the phenotypic alterations observed between sorted cells were transient and in match with the

differences in TS levels. These data strongly indicate a direct control of TS on EMT phenotype and hints that TS might have role to play in epithelial plasticity. TS REGULATES EMT GENES IN

NSCLC Further, to identify the mediators of TS-promoted EMT, RNA was sequenced from Calu-1 TSHIGH and TSLOW cells in parallel with A549 cells with TS knockdown. Where Calu-1 sorted cells

have shown growth reduction (Fig. 2c), A549 cells with TS knock-down proliferated normally (Supplementary Fig. 3A). Hence, two different cell lines that either have or don’t have a loss in

proliferation, and that are processed by two independent techniques, were subjected to investigation. Pathway analyses consistently indicated EMT among the topmost differentially regulated

pathways (Fig. 3a, b), confirming the EMT switch observed with E-CAD and VIM (Fig. 2f, j). KRT19, SPARC, SPOCK, LINC00707 (lung cancer promoting lincRNA), FOSL1 and AXL (identified as

downstream targets of TS as they appeared in both signatures) were qPCR validated in both cell lines (Fig. 3c and Supplementary Fig. 3B). Of these genes, SPARC, FOSL1 and AXL, that have an

established role in EMT in NSCLC,21,22,23 were strongly down-regulated at protein level in A549 cells with TS knockdown (Fig. 3d). Differentially expressed genes (DEGs) were used to derive a

knockdown score, which predicted a worse survival associated with lower TS knockdown (higher TS levels, Fig. 3e) and correlated with published EMT gene signature (Fig. 3f). This indicated

that TS-mediated EMT is empowered with its own prognostic impact, i.e. contributes to the adverse prognosis of NSCLC with high TS levels (Fig. 1c, d), suggesting a role for TS beyond

proliferation. Several EMT transcription factors (HMGA2, HOXC6, SNAI2, SOX9, ARNTL2, SHOX6) were identified from DEGs in endogenously TSHIGH and TSLOW cells, from which siRNA mediated

knock-down of HOXC6 and HMGA2 reduced expression of TS in Calu-1 (Supplementary Fig. 3C) and was validated in A549 (Fig. 3g). Thus, these results identified a network of TS mediated EMT,

where HOXC6 and HMGA2 are upstream of TS and AXL, SPARC and FOSL1 are downstream mediators. DEPLETION OF TS MITIGATES METASTASIS IN VIVO Finally, in vivo approaches were used to confirm the

role of TS on EMT and metastasis. Ts (mouse TS) expression was quantified in morphologically and functionally distinct mesenchymal-like (Ladi 3.1) and epithelial-like (Ladi 2.1) cells

(Supplementary Fig. 4A, B), isolated from the same mouse model of NSCLC (p53fl/fl-LSL KRASG12D/+). Ts positively correlated with Vim and negatively with E-Cad (Supplementary Fig. 4C).

Furthermore, to functionally evaluate in vivo effects of TS alteration on metastatic colonisation, _Tyms_ gene was knocked down in murine Lewis lung carcinoma cell line LL/2 using stably

transduced shRNA. A moderate Ts depletion (Fig. 4a) did not affect proliferation (Supplementary Fig. 4D), as we had previously determined from breast cancer cell lines, that TS needs to

reduce beyond a threshold to diminish proliferation.12 Furthermore, Ts knockdown also did not hamper the growth of primary tumours from the cells subcutaneously injected in flanks of

syngeneic mice (Fig. 4b). However, when injected in the tail vein, knocked down cells showed a highly significant reduction in lung metastatic colonisation (Fig. 4c, d), and the mice

carrying cells with Ts depletion showed a significantly prolonged survival (Fig. 4e). DISCUSSION TS has been widely used as a chemotherapeutic target24 ascribed to its role in proliferation.

This study experimentally validated this concept, as TS was one of the highest-ranked target gene identified based on the CRISPR/Cas9 screen analysed in this study. However,

chemotherapeutic drugs that target TS might also mitigate other detrimental features associated with cancer. We confirmed the multifaceted role of TS in proliferation and chemoresistance and

found a strong correlation with EMT gene signatures and prognosis, highlighting clinical, as well as biological relevance of TS in NSCLC. Interestingly, presented results clearly

corroborate that different functions of TS can operate independently, as observed that TS depletion can mitigate EMT phenotypes without triggering proliferation loss. This we observed in two

independent setups—first in A549, showing no loss in proliferation but alteration in EMT signature pathway after TS knockdown, and second in LL/2 cells that reduced metastatic colonisation

after TS knockdown that didn’t affect proliferation and growth of primary tumour. It strongly adds to the proliferation-independent loss of differentiation that we had previously

propounded,12,25 providing a strong rationale to revisit clinical and therapeutic aspects of TS in tumour biology and explore its therapeutic potential beyond proliferation. Pemetrexed is

used as a first-line treatment for NSCLC patients26,27 albeit response to the drug is remarkably varied. TS expression is an important determinant of sensitivity to pemetrexed16,28 and marks

the worse clinical outcomes of pemetrexed treatment in NSCLC patients.29 In agreement to this, SCC generally respond poorly to pemetrexed as compared to ADC,30 partly attributed to higher

TS expression in SCC compared to other histological subtypes.15,31 However, there is also a considerable variability to pemetrexed response within a given histological subtype.32,33 EMT

could be an additional source of variability, as it is a key driver of chemoresistance against pemetrexed in NSCLC.34 In this study we have linked higher TS expression not only to pemetrexed

outcome but also to EMT, indicating that TS has an important role in establishing a connection between EMT and pemetrexed resistance. This connection could also be extrapolated to genes

that constitute the TS regulatory network, such as FOSL1, which regulates pemetrexed resistance in coordination with EMT-TF ZEB1.22 Therefore, a more inclusive biomarker signature needs to

incorporate EMT genes and downstream genes like FOSL1, in addition to TS, for robust prediction of response to pemetrexed in NSCLC.35 TS expression has been previously shown to be stimulated

by chemotherapy, as a cellular defence mechanism,36 and these data add the notion that chemotherapy-induced TS could lead to the adjustment of EMT phenotypes in patients, that, in turn,

might influence the efficacy of treatment. This aspect could be taken into consideration for the implementation of therapeutic strategies combining EMT-suppressing drugs and chemotherapy, or

for the future design of the next generation of TS-inhibitors, which should not enhance TS levels. In NSCLC, EMT enhances the inflammatory tumour microenvironment leading to activation of

multiple immune checkpoint proteins, including PD-L1.37 A recent clinical trial has demonstrated a better outcome in NSCLC when pemetrexed is administered in combination with a PD-L1

inhibitor, pembrolizumab.38 Since, TS drives EMT and EMT has been shown to modulate response to immune therapy, a functional correlation between TS expression and susceptibility to

immunotherapy could be deduced in NSCLC. In fact, we identified interleukins such IL-6, IL-7 and IL-32 in our TS signatures, which have been previously linked with poor prognosis and

metastasis in NSCLC.39,40,41 Hence, a follow-up study is needed to validate this correlation, as the two drugs are frequently combined. The present study also underscores the plasticity of

cancer cells with mixed EMT population, as was reported in cells sorted for high and low TS expression (Supplementary Fig. 2J, K). It could be interesting to understand how TS

mechanistically drives plasticity by molecular profiling of cells at several time points between the sorting and phenotype reversal. We furthermore establish the role of TS in metastasis,

where TS knock-down abrogated the metastatic colonisation and improves mice survival without affecting proliferation and growth of primary tumour. This observation indicates that TS strongly

influences the success against selection pressure at the metastatic site. Further retrospective validation in patients can establish TS as a metastasis marker in NSCLC. Finally, this study

provides a perspective for a network that could integrate different signalling pathways to effectuate various aspects of cancer progression that are mediated by TS (Supplementary Fig. 4E),

worth further investigation. Different transcriptional regulators and effector proteins identified in this study have an established role in EMT in NSCLC and connect with master EMT-TFs.

HMGA2, for instance, affects proliferation and metastasis by regulating TWIST,42 FOSL1 regulates chemotherapy, exogenous SPARC promotes invasion and metastasis by activating SNAI121,42 and

AXL activates TWIST to affect cell cycle.23 A follow-up study could further substantiate TS as an integration point for these pathways resulting in a cumulative readout in terms of

metastasis. Thus, this study provides strong evidence that TS, apart from proliferation enzyme, also regulates EMT in NSCLC. Targeting EMT-related processes could represent a promising

therapeutic strategy to suppress the aggressiveness of TS-overexpressing NSCLC. REFERENCES * Dong, H., Wei, Y., Wan, X. & Cai, S. Hypoxia promotes human nsclc cell line A549 motility and

EMT through extracellular HSP90α. _Eur. Respir. J._ 50, PA3307 (2017). Google Scholar * Tirino, V., Camerlingo, R., Bifulco, K., Irollo, E., Montella, R., Paino, F. et al. TGF-β1 exposure

induces epithelial to mesenchymal transition both in CSCs and non-CSCs of the A549 cell line, leading to an increase of migration ability in the CD133+ A549 cell fraction. _Cell Death Dis._

4, e620–e620 (2013). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Kalluri, R. & Weinberg, R. A. The basics of epithelial-mesenchymal transition. _J. Clin. Investig._ 119,

1420–1428 (2009). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Shibue, T. & Weinberg, R. A. EMT, CSCs, and drug resistance: the mechanistic link and clinical implications.

_Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol._ 14, 611–629 (2017). Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Mittal, V. Epithelial mesenchymal transition in tumor metastasis. _Annu. Rev. Pathol._ 13,

395–412 (2018). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Tièche, C. C., Gao, Y., Bührer, E. D., Hobi, N., Berezowska, S. A., Wyler, K. et al. Tumor initiation capacity and therapy resistance

are differential features of EMT-related subpopulations in the NSCLC cell line A549. _Neoplasia_ 21, 185–196 (2019). Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar * Gonzalez, D. M. & Medici, D.

Signaling mechanisms of the epithelial-mesenchymal transition. _Sci. Signal._ 7, re8–re8 (2014). Article PubMed PubMed Central CAS Google Scholar * Larsen, J. E., Nathan, V., Osborne,

J. K., Farrow, R. K., Deb, D., Sullivan, J. P. et al. ZEB1 drives epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition in lung cancer. _J. Clin. Investig._ 126, 3219–3235 (2016). Article PubMed PubMed

Central Google Scholar * Goossens, S., Vandamme, N., Van Vlierberghe, P. & Berx, G. EMT transcription factors in cancer development re-evaluated: beyond EMT and MET. _Biochimica et.

Biophysica Acta Rev. Cancer_ 1868, 584–591 (2017). Article CAS Google Scholar * Scagliotti, G. V., Ceppi, P., Capelletto, E. & Novello, S. Updated clinical information on

multitargeted antifolates in lung cancer. _Clin. Lung Cancer_ 10, S35–S40 (2009). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Siddiqui, A., Vazakidou, M. E., Schwab, A., Napoli, F.,

Fernandez-Molina, C., Rapa, I. et al. Thymidylate synthase is functionally associated with ZEB1 and contributes to the epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition of cancer cells. _J. Pathol._ 242,

221–233 (2017). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Siddiqui, A., Gollavilli, P. N., Schwab, A., Vazakidou, M. E., Ersan, P. G., Ramakrishnan, M. et al. Thymidylate synthase maintains

the de-differentiated state of triple negative breast cancers. _Cell Death Differ._ 26, 2223–2236 (2019). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Shi, S., Wang, R., Chen, Y.,

Song, H., Chen, L. & Huang, G. Combining antiangiogenic therapy with adoptive cell immunotherapy exerts better antitumor effects in non-small cell lung cancer models. _PLoS ONE._ 8,

e65757 (2013). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Behan, F. M., Iorio, F., Picco, G., Gonçalves, E., Beaver, C. M., Migliardi, G. et al. Prioritization of cancer

therapeutic targets using CRISPR–Cas9 screens. _Nature_ 568, 511–516 (2019). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Ceppi, P., Volante, M., Saviozzi, S., Rapa, I., Novello, S., Cambieri, A.

et al. Squamous cell carcinoma of the lung compared with other histotypes shows higher messenger RNA and protein levels for thymidylate synthase. _Cancer_ 107, 1589–1596 (2006). Article

CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Takezawa, K., Okamoto, I., Okamoto, W., Takeda, M., Sakai, K., Tsukioka, S. et al. Thymidylate synthase as a determinant of pemetrexed sensitivity in non-small

cell lung cancer. _Br. J. Cancer_ 104, 1594–1601 (2011). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Schwab, A., Siddiqui, A., Vazakidou, M. E., Napoli, F., Böttcher, M.,

Menchicchi, B. et al. Polyol pathway links glucose metabolism to the aggressiveness of cancer cells. _Cancer Res._ 78, 1604–1618 (2018). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Ceppi, P.,

Rapa, I., Lo Iacono, M., Righi, L., Giorcelli, J., Pautasso, M. et al. Expression and pharmacological inhibition of thymidylate synthase and Src kinase in nonsmall cell lung cancer. _Int J.

Cancer_. 130, 1777–1786 (2012). * Kurtova, A. V., Xiao, J., Mo, Q., Pazhanisamy, S., Krasnow, R., Lerner, S. P. et al. Blocking PGE2-induced tumour repopulation abrogates bladder cancer

chemoresistance. _Nature_ 517, 209–213 (2015). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Karacosta, L. G., Anchang, B., Ignatiadis, N., Kimmey, S. C., Benson, J. A., Shrager, J. B. et al.

Mapping lung cancer epithelial-mesenchymal transition states and trajectories with single-cell resolution. _Nat. Commun._ 10, 5587 (2019). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google

Scholar * Hung, J.-Y., Yen, M.-C., Jian, S.-F., Wu, C.-Y., Chang, W.-A., Liu, K.-T. et al. Secreted protein acidic and rich in cysteine (SPARC) induces cell migration and epithelial

mesenchymal transition through WNK1/snail in non-small cell lung cancer. _Oncotarget_ 8, 63691–63702 (2017). Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Chiu, L. Y., Hsin, I. L.,

Yang, T. Y., Sung, W. W., Chi, J. Y., Chang, J. T. et al. The ERK-ZEB1 pathway mediates epithelial-mesenchymal transition in pemetrexed resistant lung cancer cells with suppression by vinca

alkaloids. _Oncogene_ 36, 242–253 (2017). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Ying, X., Chen, J., Huang, X., Huang, P. & Yan, S. Effect of AXL on the epithelial-to-mesenchymal

transition in non-small cell lung cancer. _Exp. therapeutic Med._ 14, 785–790 (2017). Article CAS Google Scholar * Wilson, P. M., Danenberg, P. V., Johnston, P. G., Lenz, H. J. &

Ladner, R. D. Standing the test of time: targeting thymidylate biosynthesis in cancer therapy. _Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol._ 11, 282–298 (2014). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Siddiqui,

A. & Ceppi, P. A non-proliferative role of pyrimidine metabolism in cancer. _Mol. Metab._ 35, 100962 (2020). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Manegold, C.,

Gatzemeier, U., Von Pawel, J., Pirker, R., Malayeri, R., Blatter, J. et al. Front-line treatment of advanced non-small-cell lung cancer with MTA (LY231514, pemetrexed disodium, ALIMTA) and

cisplatin: a multicenter phase II trial. _Ann. Oncol._ 11, 435–440 (2000). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Scagliotti, G. V., Novello, S., Crino, L. & Rosell, R. Pemetrexed in

front-line chemotherapy for advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. _Oncology_ 18, 32–37 (2004). PubMed Google Scholar * Ozasa, H., Oguri, T., Uemura, T., Miyazaki, M., Maeno, K., Sato, S. et

al. Significance of thymidylate synthase for resistance to pemetrexed in lung cancer. _Cancer Sci._ 101, 161–166 (2010). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Liu, Y., Yin, T.-J., Zhou,

R., Zhou, S., Fan, L. & Zhang, R.-G. Expression of thymidylate synthase predicts clinical outcomes of pemetrexed-containing chemotherapy for non-small-cell lung cancer: a systemic review

and meta-analysis. _Cancer Chemother. Pharmacol._ 72, 1125–1132 (2013). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Socinski, M. A., Smit, E. F., Lorigan, P., Konduri, K., Reck, M., Szczesna,

A. et al. Phase III study of pemetrexed plus carboplatin compared with etoposide plus carboplatin in chemotherapy-naive patients with extensive-stage small-cell lung cancer. _J. Clin.

Oncol._ 27, 4787–4792 (2009). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Monica, V., Scagliotti, G. V., Ceppi, P., Righi, L., Cambieri, A., Lo Iacono, M. et al. Differential thymidylate

synthase expression in different variants of large-cell carcinoma of the lung. _Clin. Cancer Res._ 15, 7547–7552 (2009). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Scagliotti, G. V., Parikh,

P., Von Pawel, J., Biesma, B., Vansteenkiste, J., Manegold, C. et al. Phase III study comparing cisplatin plus gemcitabine with cisplatin plus pemetrexed in chemotherapy-naive patients with

advanced-stage non–small-cell lung cancer. _J. Clin. Oncol._ 26, 3543–3551 (2008). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Scagliotti, G., Hanna, N., Fossella, F., Sugarman, K., Blatter, J.,

Peterson, P. et al. The differential efficacy of pemetrexed according to NSCLC histology: a review of two phase III studies. _Oncologist_ 14, 253–263 (2009). Article CAS PubMed Google

Scholar * Liang, S. Q., Marti, T. M., Dorn, P., Froment, L., Hall, S. R. R., Berezowska, S. et al. Blocking the epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition pathway abrogates resistance to

anti-folate chemotherapy in lung cancer. _Cell Death Dis._ 6, e1824–e1824 (2015). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Visser, S., Hou, J., Bezemer, K., De Vogel, L. L.,

Hegmans, J. P. J. J., Stricker, B. H. et al. Prediction of response to pemetrexed in non-small-cell lung cancer with immunohistochemical phenotyping based on gene expression profiles. _BMC

Cancer_ 19, 440 (2019). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Longley, D. B., Harkin, D. P. & Johnston, P. G. 5-Fluorouracil: mechanisms of action and clinical

strategies. _Nat. Rev. Cancer_ 3, 330–338 (2003). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Lou, Y., Diao, L., Cuentas, E. R. P., Denning, W. L., Chen, L., Fan, Y. H. et al.

Epithelial–mesenchymal transition is associated with a distinct tumor microenvironment including elevation of inflammatory signals and multiple immune checkpoints in lung adenocarcinoma.

_Clin. Cancer Res._ 22, 3630–3642 (2016). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Gandhi, L., Rodríguez-Abreu, D., Gadgeel, S., Esteban, E., Felip, E., De Angelis, F. et al.

Pembrolizumab plus chemotherapy in metastatic non–small-cell lung cancer. _N. Engl. J. Med._ 378, 2078–2092 (2018). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Sorrentino, C. & Carlo, E. D.

Expression of IL-32 in human lung cancer is related to the histotype and metastatic phenotype. _Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med._ 180, 769–779 (2009). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar *

Silva, E. M., Mariano, V. S., Pastrez, P. R. A., Pinto, M. C., Castro, A. G., Syrjanen, K. J. et al. High systemic IL-6 is associated with worse prognosis in patients with non-small cell

lung cancer. _PLoS ONE_ 12, e0181125 (2017). Article PubMed PubMed Central CAS Google Scholar * Roato, I., Caldo, D., Godio, L., D’amico, L., Giannoni, P., Morello, E. et al. Bone

invading NSCLC cells produce IL-7: mice model and human histologic data. _BMC Cancer_ 10, 12 (2010). Article PubMed PubMed Central CAS Google Scholar * Gao, X., Dai, M., Li, Q., Wang,

Z., Lu, Y. & Song, Z. HMGA2 regulates lung cancer proliferation and metastasis. _Thorac. Cancer_ 8, 501–510 (2017). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar Download

references ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS We would like to thank Dr. Markus Diefenbacher, Deptartment of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, University of Würzburg for providing Ladi cells and Prof. Dr.

Susetta Finotto, Deptartment of Molecular Pneumology, University Hospital Erlangen, for LL/2 cells. The sorting was performed at Core Unit for Cell Sorting and Immunomonitoring at Nikolaus

Fiebiger Zentrum, Friedrich-Alexander University of Erlangen Nuremberg. Results were partially presented at the 18th World Conference on Lung Cancer in Yokohama, Japan. AUTHOR INFORMATION

Author notes * These authors contributed equally: Mohammad Aarif Siddiqui, Paradesi Naidu Gollavilli. AUTHORS AND AFFILIATIONS * Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, University

of Southern Denmark, Odense, Denmark Mohammad Aarif Siddiqui & Paolo Ceppi * Interdisciplinary Center for Clinical Research (IZKF), Friedrich-Alexander University of Erlangen-Nuremberg,

Erlangen, Germany Mohammad Aarif Siddiqui, Paradesi Naidu Gollavilli, Vignesh Ramesh, Beatrice Parma, Annemarie Schwab, Maria Eleni Vazakidou & Paolo Ceppi * Perelman School of Medicine,

University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA, USA Ramakrishnan Natesan & Irfan Ahmed Asangani * Department of Drug Discovery and Biomedical Sciences, University of South Carolina,

Columbia, SC, USA Ozge Saatci & Ozgur Sahin * Department of Oncology at San Luigi Hospital, University of Turin, Orbassano, Turin, Italy Ida Rapa, Paolo Bironzo & Marco Volante *

Department of Experimental Medicine-I, Friedrich-Alexander University of Erlangen-Nuremberg, Erlangen, Germany Harald Schuhwerk Authors * Mohammad Aarif Siddiqui View author publications You

can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Paradesi Naidu Gollavilli View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Vignesh Ramesh

View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Beatrice Parma View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar *

Annemarie Schwab View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Maria Eleni Vazakidou View author publications You can also search for this author

inPubMed Google Scholar * Ramakrishnan Natesan View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Ozge Saatci View author publications You can also search

for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Ida Rapa View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Paolo Bironzo View author publications You can also

search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Harald Schuhwerk View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Irfan Ahmed Asangani View author

publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Ozgur Sahin View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Marco Volante

View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Paolo Ceppi View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar

CONTRIBUTIONS M.A.S. was involved in conception, design, acquisition, and analysis of in vitro experimental data and drafting of the paper. P.N.G. was involved in acquisition and analysis of

in vivo experimental data. V.R. was involved in data acquisition and bioinformatic analysis. B.P., A.S. and M.E.V. were involved in in vitro data acquisition, R.N. performed RNA-sequencing,

O.S. (Ozge Saatci) performed analysis of RNA-Seq data, I.R. and P.B. acquired patient data, H.S. helped in design of the in vivo work, I.A.A. helped with interpretation of RNA-seq Data,

O.Sa (Ozgur Sahin) helped with generation and interpretation of knock down score and critical revision of the paper, M.V. was involved in interpretation of patient data and critical revision

of the paper, P.C. was involved in project supervision, experimental conceptualisation and design, analysis and interpretation of data and drafting of paper. All authors read and approved

the final paper. CORRESPONDING AUTHOR Correspondence to Paolo Ceppi. ETHICS DECLARATIONS ETHICS APPROVAL AND CONSENT TO PARTICIPATES The use of retrospective solid tumour tissues for the

immunohistochemical and qPCR study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the San Luigi Hospital/University of Turin (approvals n.167/2015 and 204/2016). Informed consent was

obtained from all patients. In vivo experiments were performed by skilled experimenters trained according to FELASA guidelines. Animal protocols were approved by the Institutional Animal

Care and Use Committee of the Regierung von Unterfranken. DATA AVAILABILITY Data from RNA-seq has been submitted to GEO database (Accession Number: GSE148589) COMPETING INTERESTS The authors

declare no competing interests. FUNDING INFORMATION Work supported by the Interdisciplinary Centre for Clinical Research (IZKF) of the Friedrich-Alexander University of Erlangen‐Nuremberg

(Junior Group 1), the IALSC Young Investigator Award (to P.C.) and National Institutes of Health Grant 2P20GM109091-06 (to O.Sahin). Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt

DEAL. ADDITIONAL INFORMATION PUBLISHER’S NOTE Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL RIGHTS AND PERMISSIONS OPEN ACCESS This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation,

distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and

indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to

the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will

need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. Reprints and permissions ABOUT THIS ARTICLE

CITE THIS ARTICLE Siddiqui, M.A., Gollavilli, P.N., Ramesh, V. _et al._ Thymidylate synthase drives the phenotypes of epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition in non-small cell lung cancer. _Br

J Cancer_ 124, 281–289 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41416-020-01095-x Download citation * Received: 23 April 2020 * Revised: 20 August 2020 * Accepted: 04 September 2020 * Published: 07

October 2020 * Issue Date: 05 January 2021 * DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41416-020-01095-x SHARE THIS ARTICLE Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Get shareable link Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article. Copy to clipboard Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative