Efficacy of a nurse-led sexual rehabilitation intervention for women with gynaecological cancers receiving radiotherapy: results of a randomised trial

- Select a language for the TTS:

- UK English Female

- UK English Male

- US English Female

- US English Male

- Australian Female

- Australian Male

- Language selected: (auto detect) - EN

Play all audios:

ABSTRACT BACKGROUND The multicentre randomised SPARC trial evaluated the efficacy of a nurse-led sexual rehabilitation intervention on sexual functioning, distress, dilator use, and vaginal

symptoms after radiotherapy for gynaecological cancers. METHODS Eligible women were randomised to the rehabilitation intervention or care-as-usual. Four intervention sessions were scheduled

over 12 months, with concurrent validated questionnaires and clinical assessments. Primary outcome was the Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI). A generalised-mixed-effects model compared

groups over time. RESULTS In total, 229 women were included (_n_ = 112 intervention; _n_ = 117 care-as-usual). No differences in FSFI total scores were found between groups at any timepoint

(_P_ = 0.37), with 12-month scores of 22.57 (intervention) versus 21.76 (care-as-usual). The intervention did not significantly improve dilator use, reduce sexual distress or vaginal

symptoms compared to care-as-usual. At 12 months, both groups had minimal physician-reported vaginal stenosis; 70% of women were sexually active and reported no or mild vaginal symptoms.

After radiotherapy and brachytherapy, 85% (intervention) versus 75% (care-as-usual) of participants reported dilation twice weekly. DISCUSSION Sexual rehabilitation for women treated with

combined (chemo)radiotherapy and brachytherapy improved before and during the SPARC trial, which likely contributed to comparable study groups. Best practice involves a sexual rehabilitation

appointment 1 month post-radiotherapy, including patient information, with dilator guidance, preferably by a trained nurse, and follow-up during the first year after treatment. CLINICAL

TRIAL REGISTRATION NCT03611517. SIMILAR CONTENT BEING VIEWED BY OTHERS SEXUAL FUNCTION AND REHABILITATION AFTER RADIATION THERAPY FOR PROSTATE CANCER: A REVIEW Article 06 January 2021

PSYCHOSOCIAL CONTRIBUTORS TO PATIENTS’ AND PARTNERS’ POSTPROSTATE CANCER SEXUAL RECOVERY: 10 EVIDENCE-BASED AND PRACTICAL CONSIDERATIONS Article 17 November 2020 EFFECT OF PLISSIT MODEL

COUNSELING ON THE SEXUAL QUALITY OF LIFE OF INFERTILE WOMEN: A RANDOMIZED CONTROLLED TRIAL Article Open access 29 May 2025 BACKGROUND Women with locally advanced cervical and vaginal cancer

are primarily treated with external beam radiotherapy with concurrent cisplatin-based chemotherapy and MRI-guided adaptive brachytherapy. Those with early-stage cervical or endometrial

cancer treated with upfront surgery receive adjuvant external beam radiotherapy (with or without brachytherapy boost) in case of lymph node involvement, close or involved surgical margins or

a combination of risk factors. The impact of these gynaecological cancer treatments on sexual functioning can be substantial and is more pronounced when radiotherapy is included, as

compared to surgery alone [1, 2]. Especially treatment with both external beam radiotherapy and brachytherapy has been shown to impact vaginal and sexual functioning by causing morphological

changes in the vaginal mucosa, such as atrophy, adhesions, and fibrosis which may lead to vaginal stenosis and shortening [3,4,5]. Regular vaginal dilation has been shown to help prevent

and reduce vaginal stenosis [6]. However, many women (75%) fail to use dilators regularly, even with counselling and specific instructions [7, 8]. Some studies suggested that additional

professional support, including psycho-education and motivation, can improve compliance [6], but not all studies showed such benefit [9, 10]. In addition, reported interventions targeting

dilator use did not address other psychosexual consequences of treatment of gynaecological cancer, such as sexual distress and (worries about) pain during intercourse [3, 7, 11]. Some small

studies have investigated psychosexual interventions such as cognitive behavioural techniques, psycho-education and counselling to address sexual problems after radiotherapy [5, 11,12,13].

Results indicated that such interventions can lead to improved sexual functioning, reduced sexual distress, and when the partner was actively involved, enhanced relationship satisfaction. In

a previous pilot study, a specifically developed nurse-led sexual rehabilitation intervention combining psycho-education and cognitive behavioural therapy was shown to improve sexual

functioning and compliance with dilator use in women treated with chemoradiotherapy and brachytherapy [14]. Subsequently a randomised trial was designed to evaluate the effectiveness of this

rehabilitation intervention as compared to care-as-usual. We hypothesised that women receiving this nurse-led rehabilitation intervention would experience significantly greater improvement

in sexual functioning at 12 months after radiotherapy. In addition, we anticipated improved compliance with dilator use and fewer vaginal functioning problems and sexual distress. METHODS

STUDY DESIGN AND PARTICIPANTS The SPARC (Sexual rehabilitation Programme After Radiotherapy for gynaecological Cancer, NCT03611517) study was a multicentre randomised trial conducted in all

10 Dutch gynaecological oncology centres. Participating centres, including their study teams, are listed in Supplementary Appendix 1 (p. 1). A detailed description of the trial design has

been previously reported [15]. Before start of the trial, a study-specific 50-h training programme was held, to which each participating centre sent at least two designated oncology nurses

(for details, see Table 1) [14, 15]. Only after completing this programme, nurses were allowed to conduct the intervention. An additional training programme and annual focused training days

were organised during the years of the study. Eligible women had a histological diagnosis of cervical, vaginal or endometrial cancer; received primary or postoperative external beam

radiotherapy with or without concurrent chemotherapy and brachytherapy, or postoperative radiotherapy alone; were 18 years or older, and intended to retain sexual activity. Both single and

partnered women, regardless of their sexual orientation, could participate. Exclusion criteria were unavailability for follow-up; insufficient Dutch language proficiency; major affective,

psychotic or substance abuse disorder, or posttraumatic stress disorder related to pelvic floor/genital abuse. The radiation oncologists at the participating centres screened potential

participants. Eligible women were informed about the background, rationale and specifics of the study protocol. All participating women provided written informed consent and completed a

baseline questionnaire before completion of radiotherapy. In this baseline questionnaire they retrospectively completed questions about sexual functioning and distress prior to cancer

symptoms and diagnosis. The protocol was approved by the Scientific Review Board of the Dutch Cancer Society, by the Medical Ethics Committee Leiden-Den Haag-Delft (number NL62767.058.17),

and by the Institutional Review Boards and/or Ethics Committees of the participating centres. RANDOMISATION AND MASKING Participants were assigned unique study identifiers by the local data

manager for use in all questionnaires and data files. Participants were randomly assigned (1:1) to the nurse-led sexual rehabilitation intervention or care-as-usual, using block stratified

randomisation (block sizes of 2 and 4). Stratification was based on radiotherapy type (brachytherapy yes/no) and partner status (yes/no). Participants were registered by the local data

manager through a secured web-based system, and randomised after completing baseline measurements. Participants, physicians, nurses, and investigators were not masked to treatment

allocation. PROCEDURES In the intervention group, all women were counselled and followed by a specifically trained nurse [14]. The content of this nurse-led sexual rehabilitation

intervention has been described in detail elsewhere [15] and is summarised in Table 1 and Fig. 1. In short, the intervention comprised four 1-h face-to-face sessions at 1, 3, 6 and 12 months

post-radiotherapy, synchronised with visits to the radiation oncologist, with an extra session at 2 months for women who received brachytherapy. All nurse-led intervention sessions were

audio-taped for checks of adherence to the protocol and assessment of competence by an independent panel. The aim was to conduct random checks of 15% of the sessions, which is customary in

this type of research, where a minimum of 10% is considered acceptable within large cohorts [16]. Both the intervention and care-as-usual groups had a first follow-up session 4–5 weeks after

completion of radiotherapy with their radiation oncologist, to evaluate recovery, tumour regression and vaginal healing, and to assess symptoms. All women received a specially developed

information booklet which was based on the pilot study [14]. Those who had received radiotherapy with brachytherapy also received a vaginal dilator set (Amielle Comfort®; Owen Mumford) and

two tubes of lubrication gel (K-Y Jelly; Johnson & Johnsen) free of charge. They were advised to start vaginal dilation for 1–3 min, 2–3 times a week, provided the vagina was

sufficiently healed, and to continue regular vaginal dilation throughout the first year after radiotherapy. If sexual intercourse was resumed, this was also considered as part of vaginal

dilation, which could be complemented with the use of the dilator set. Women with cervical or vaginal cancers who were under 50 years of age were recommended to receive hormone replacement

therapy until the age of about 50. Prior to the study, the study team at the centres had been queried about their standard protocols regarding sexual rehabilitation within their centre

(‘care-as-usual’). In most of the centres (90%), specific counselling on sexual rehabilitation and dilation was already a standard topic of information after treatment and during follow-up

appointments with their physician. Although the guidance offered to the care-as-usual group could not be completely standardised due to these local practices, it did not involve the

structured, tailored nurse-led sexual rehabilitation intervention during follow-up. OUTCOMES The primary outcome was overall sexual functioning, as measured with the Female Sexual Function

Index (FSFI) [17]. A total score of ≤26.55 has been validated as the cut-off score for diagnosis of female sexual dysfunction [18]. We added two questions to the FSFI to assess the frequency

of sexual activity with and without sexual intercourse. Secondary outcomes included sexual distress, as measured by the Female Sexual Distress Scale (FSDS; scores ≥15 have been signified to

establish the presence of sexual distress) [19], compliance with dilator use (assessed using a 4-item questionnaire regarding frequency, duration, sexual intercourse and other vaginal

penetration activities), vaginal functioning problems such as shortness, dryness and pain during intercourse (measured by the Cervical Cancer Module of the European Organization for Research

and Treatment of Cancer (QLQ-CX24) [20]), and physician-reported vaginal dryness, shortening and/or tightening, and dyspareunia (assessed by standardised clinical examination using the

Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE, version 4.03)). See Supplementary Appendix 2 (p. 2) for additional specific patient and physician-reported outcome measures, with

cut-off scores if applicable. Outcomes were assessed before radiotherapy (retrospective baseline) and 1, 3, 6 and 12 months after radiotherapy. To minimise respondent burden, the baseline

questionnaire included only the FSFI and the FSDS. Adverse events related to dilator use were documented. Cancer treatment-related adverse events were not considered study-related.

STATISTICAL ANALYSIS An effect size of _d_ = 0.50 indicates a moderate and clinically relevant effect size [21]. This corresponds with a difference of 3.4 points on the primary outcome

measure (FSFI), with a standard deviation of 6.8. To achieve 80% power at a 0.05 significance level, each study group required a minimum of 64 evaluable women at 12 months. Considering the

40% dropout rate observed in the pilot study [14], at least 107 women in both the intervention and care-as-usual group were required, stratified by radiotherapy type and partner status.

During participant recruitment, it became evident that women undergoing both external beam radiotherapy and brachytherapy were more likely to participate, probably due to more advanced age

and milder side effects in those receiving pelvic radiotherapy alone. Consequently, the study population comprised relatively young women with cervical carcinoma primarily treated with

external beam radiotherapy, concurrent cisplatin-based chemotherapy, and image-guided adaptive brachytherapy. Given the intervention’s relevance to these younger women with intensive

treatment for cervical and vaginal carcinomas, we decided to continue the enrolment of eligible women regardless of radiotherapy type to a total of 220 women. The study was amended

accordingly. Analyses were based on intention-to-treat and were conducted with the Statistical Package for Social scientists (version 29) and the GLMM-adaptive package in R (version 4.2.1)

[22]. Questionnaire scores were calculated using published algorithms [17, 19, 20]. Missing values were replaced by the average score of completed items on the same scale for each

individual, when ≥75% of items were completed. When a scale consisted of only two items, 100% of the items had to be completed. To address differences in changes in the primary and secondary

outcome measures between groups (intervention versus care-as-usual) over time we modelled either the mean scores, log expected counts or log odds (depending on the type of variable) as a

function of time, of the intervention group and their interaction. In addition, radiotherapy with or without brachytherapy was added as factor to the model. For the physician-reported

variables, when fewer than 15 women scored within CTCAE grade 2 and/or 3 events, these scores were combined into a single category with CTCAE grade 1 (‘toxicity’), and then compared to CTCAE

grade 0 (‘no toxicity’). Differences between groups were evaluated based on a generalised linear mixed effects model, specifically depending on the outcome considered we used mixed effects

poisson regression (count measurements) or mixed effects logistic regression (dichotomous outcomes). We used a beta distribution instead of a normal distribution for our continuous outcomes,

because of the bounded nature of these outcomes (e.g. the FSFI total score takes values between 2 and 36 [17]). In addition, we used a random effects model (i.e., random intercepts and

random slopes) to capture the within-subjects correlation. We further explored if there was considerable between-hospital variability. Regarding missing data, the generalised linear mixed

effects models give valid results under the missing at random mechanism. To account for any potential model misspecification robust standard errors were computed. We used the Likelihood

Ratio Test to test whether the improvement of the intervention group over time was statistically significantly different from the care-as-usual group. The significance level was set at 0.05.

This study was monitored for trial and data compliance by an independent certified monitor and registered under ClinicalTrials.gov number NCT03611517. RESULTS Between Aug 7, 2018, and Dec

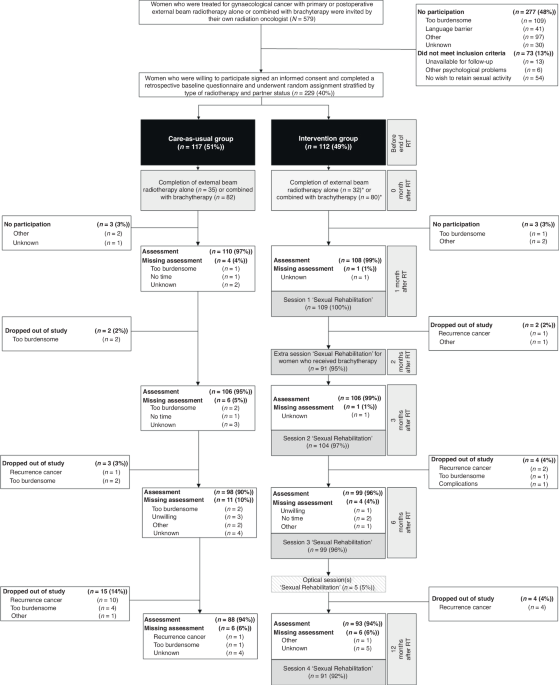

31, 2021, 229 women were enrolled and randomly assigned to the nurse-led sexual rehabilitation intervention (_n_ = 112, 49%) or to care-as-usual (_n_ = 117, 51%) (see Fig. 1). 36 women (16%)

discontinued participation before the 12-month assessment. Dropout was significantly lower in the intervention group (_n_ = 13, 12%) than in the care-as-usual group (_n_ = 23, 20%) (_P_

< 0.001). Follow-up and/or questionnaire data of 39 women (17%) were not available at one or more timepoints during the 12-month follow-up period: 12 (11%) in the intervention group; 27

(23%) in the care-as-usual group). Patient, disease and treatment characteristics were well-balanced between the two groups (see Table 2). Most women were treated with primary or

postoperative external beam radiotherapy combined with brachytherapy (80 (71%) in the intervention group; 82 (70%) in the care-as-usual group) for cervical cancer (98 (87.5%) for the

intervention group; 104 (89%) for the care-as-usual group), and had a partner (88 (79%) for the intervention group; 90 (77%) for the care-as-usual group); with mostly male partners (86 (98%)

for the intervention group; 90 (100%) for the care-as usual group). Approximately 70% of the women under the age of 50 with cervical cancer received hormonal replacement therapy during

follow-up. Women in the intervention group had on average 4.4 (SD = 1.1) intervention sessions, lasting on average 31 min (SD = 14.6) per session. Most sessions were face-to-face: 102 (94%),

49 (56%), 80 (77%), 68 (69%), 65 (71%) for 1, 2, 3, 6 and 12 months after radiotherapy, respectively. The participation of partners declined over time: among the 88 women in the

intervention group with a partner, 40 partners (45.5%) participated at the 1-month session, 31 (35%) at 3 months, 21 (24%) at 6 months, and 14 (17%) at 12 - months after radiotherapy.

Twenty partners of the 74 partnered women in each arm in the radiotherapy with brachytherapy group (27%) participated in the 2-month session focusing on dilator use. Random checks of

protocol adherence and competence assessment indicated a 90% adherence and competence rate. There were no sexual rehabilitation or dilator use-related serious adverse events. Regarding the

primary outcome FSFI, for both study groups scores were clearly decreased after radiotherapy (compared to the retrospective baseline scores), whereafter they increased over time. At 12

months, FSFI total scores were 22.57 in the intervention group versus 21.76 in the care-as-usual group, see Fig. 2I-II. As the FSFI is very sensitive to sexual activity, we also show the

mean scores of sexually active women (with or without intercourse) and women not sexually active. At 12 months, 67 (71%) women in the intervention group and 60 (69%) women in the

care-as-usual group were sexually active, with 65 (69%) women in the intervention group and 56 (64%) women in the care-as-usual group reporting sexual intercourse (see Supplementary Appendix

3, p. 4). As shown in Fig. 2I-II, FSFI scores for women not sexually active were lower than for sexually active women, while the pattern of decrease and increase over time was similar in

both groups. Regarding our secondary outcomes, compared to the situation prior to diagnosis, sexual distress as measured by the FSDS was strongly increased after radiotherapy, whereafter it

remained elevated over time (see Fig. 2III). Almost half of the women reported sexual distress to a clinical degree at 12 months after radiotherapy in both study groups (42 (45%) women in

the intervention group versus 40 (46%) women in the care-as-usual group, see Supplementary Appendix 6, p. 17). Figure 3I-III shows that the majority of the women in both groups had no

physician-reported vaginal stenosis, dryness, and dyspareunia during follow-up, followed by grade 1 (not interfering with sexual functioning). Grade 1 vaginal stenosis was seen in 8 (7.5%,

intervention group) and 4 (3%, care-as-usual group) women at baseline (before radiotherapy), gradually increasing to 21 (24%) women in the intervention group and 20 (23%) women in the

care-as-usual group at 12 months after radiotherapy. Grade 1 vaginal dryness was reported in 2 (2%, intervention group) and 4 (4%, care-as-usual group) women before radiotherapy, increasing

to 18 (21%) and 26 (32%) women, respectively, at 12 months after radiotherapy. Grade 1 dyspareunia was assessed in 3 (4%, intervention group) and 10 (12%, care-as-usual group) women before

radiotherapy, increasing to 24 (29%) and 14 (20%) women, respectively, at 12 months after radiotherapy. There was no clear increase or decrease in patient-reported feelings of vaginal

shortness, dryness and pain during intercourse in the follow-up period (Fig. 3IV–VI), with most sexually active women reporting ‘none’ or ‘a little’ (respectively, 61 (87%), 55 (78.5%) and

64 (91.5%) in the intervention group and 54 (87%), 54 (87%) and 58 (93.5%) in the care-as-usual group at 12 months after radiotherapy). At 12 months, more substantial (‘quite a bit’ or ‘very

much’) feelings of vaginal shortness, dryness and pain during intercourse were reported by 9 (13%), 15 (21%) and 6 (9%) sexually active women in the intervention group versus 8 (13%), 8

(13%), and 4 (6.5%) sexually active women in the care-as-usual group, respectively. See Supplementary Appendixes 4 and 5 (p. 15–16) for additional physician and patient-reported outcomes on

vaginal functioning. Figure 4 shows the patient-reported dilation by the arm for women in the external beam radiotherapy combined with the brachytherapy group. Any type of dilation used at

least two times per week, including dilators, vibrators, dildos, fingers or intercourse combined, that was employed by women who received brachytherapy, was reported by 66 (69.5%) women in

the intervention group and 60 (64.5%) women in the care-as-usual group at 1 month after radiotherapy, increasing to 90 (97%) women and 82 (90%) women at 3 months after radiotherapy,

respectively (Fig. 4IV). Any type of dilation ≥2 times per week slightly decreased to 70 (85%) women in the intervention group, and 57 (75%) women in the care-as-usual group at 12 months

after radiotherapy. Likelihood ratio tests indicated no significant improvement in model fit when including the treatment group (_P_ > 0.05). No differences in FSFI total scores were

found between the groups at any timepoint (_P_ = 0.37). This suggests that the sexual rehabilitation intervention had no significant impact on better sexual functioning compared to the

care-as-usual group. This result applied to most (95%) of the other outcomes (for more details, see Supplementary Appendix 3, p. 3–14). DISCUSSION The SPARC trial is to our knowledge the

first robustly powered randomised trial to investigate the efficacy of a nurse-led sexual rehabilitation intervention to improve sexual recovery and compliance with dilator use for women

treated with radiotherapy and brachytherapy for gynaecological cancers. Contrary to expectations based on the pilot study [14], this trial did not show a significant benefit of the nurse-led

sexual rehabilitation intervention over care-as-usual in improving sexual functioning, dilator compliance, and reducing sexual distress and vaginal symptoms, 1 year after radiotherapy.

However, compared to previous data on similar treatments, women in both study groups had relatively high rates of sexual activity, with overall 70% reporting to be sexually active at 12

months, compared to 40–50% in previous studies [1, 2, 4]. Most women in both study groups had no or little physician-reported vaginal stenosis, with most sexually active women reporting no

or only a little feeling of vaginal shortness, dryness and pain during intercourse at 12 months after radiotherapy. Substantial vaginal and sexual functioning problems were rare. Also, any

dilation ≥2 times weekly, including dilators, vibrators, dildos, fingers or intercourse combined, was reported by 85% of the participants in the intervention group and by 75% of the

participants in the care-as-usual group at 12 months, similar to the pilot study [14]. Almost half of the women in both groups continued to experience clinical-level sexual distress even at

the 12-month post-radiotherapy follow-up, indicating the complexity of sexual functioning. The lack of notable differences in outcomes between the two groups is likely explained by the fact

that both healthcare professionals in gynaecological oncology and patient advocacy groups have become more aware of the importance of early sexual rehabilitation care and associated issues

since the start of the trial. Since the completion of the pilot study [14], standard sexual rehabilitation care in the Netherlands already involved a one-month post-radiotherapy appointment

with a physician or nurse. During this appointment, women received comprehensive verbal and written information on sexual rehabilitation. In addition, a vaginal dilator set with lubrication

gel was provided free of charge to women who had undergone pelvic radiotherapy with brachytherapy, along with explicit guidance on use, both within and outside of trial participation. The

comprehensive training of the nurses conducting the intervention in the SPARC trial led to further in-depth knowledge, and to increased skills in informing and coaching and addressing

specific personal issues and questions for these women across all centres, including in most centres those randomised to the care-as-usual group. In addition, during the study, the Dutch

patient advocacy group for women with gynaecological cancers (Olijf) developed a specialised patient website focused on sexual rehabilitation [23]. The website’s widespread visibility and

accessible information on sexuality and post-treatment rehabilitation were shared with all trial participants, fostering informal discussions among patients in online forums and with

caregivers, both at the treatment centres and beyond. To gain a more comprehensive understanding of the coaching and information of the women randomised to the care-as-usual group, we

incorporated post hoc questionnaires for the centres about their standard care. The responses revealed that six out of ten centres had implemented additional improvements to standard sexual

rehabilitation care during the study period, and that half of the centres had arranged at least one additional care pathway appointment within the first year after radiotherapy, with a

specific focus on sexuality. Moreover, all centres ensured that sexuality remained a standard topic in all follow-up appointments with physicians. As the sexual rehabilitation sessions with

the nurse were directly scheduled after these appointments, sexuality was discussed at the same timepoints in both study groups. Women with cervical cancer constituted the large majority

(88%) of the current study population, making our study outcomes particularly relevant for these relatively young women treated with intensive combined chemoradiotherapy and brachytherapy.

The trial’s guidelines on sexual rehabilitation align with recent guidelines that advocate for heightened attention to post-radiotherapy sexual functioning in gynaecological cancer patients,

including those treated with pelvic radiotherapy alone, albeit with more emphasis on rehabilitation after treatment in general and less on vaginal dilation [24, 25]. Considering that nurses

can devote more time to patient interaction, are often easily accessible for patients, and can integrate their role in information and counselling in other clinical tasks, their role would

be a cost-effective strategy for dedicated sexual rehabilitation. The cost-effectiveness of the nurse-led intervention versus care-as-usual is topic of subsequent analysis. This trial has

several notable strengths, including the well-powered randomised trial design, the participation of all Dutch gynaecological oncology centres, a limited dropout of study participants, the

use of a clear treatment protocol and extensive training protocol, including an adherence and competency assessment by an independent panel, and the invitation to the women’s partners to

join the intervention sessions. This study also has some limitations. First, as it turned out, the improvements in standard sexual rehabilitation after completion of radiation therapy may

have unintentionally impacted on care of the care-as-usual group. Despite instructions to physicians and nurses to manage both study groups differently, their involvement with both study

groups may have resulted similar initial post-radiotherapy psychosexual care. This well-known problem of contamination within individually randomised intervention studies could have been

avoided by cluster randomisation (i.e., on the centre level instead of the patient level). However, this method also introduces other potential threats to internal validity, as the number of

centres in our study is limited and only a part of the centres could be randomised (_n_ = 8, as a consequence of the training that was already completed in two centres for the pilot study)

[14]. Because of the specific variation in the patient population, radiotherapy treatment procedures and follow-up procedures across centres, we decided to randomise on the patient level.

Furthermore, the FSFI, which is widely employed to evaluate sexual functioning in female cancer survivors, could yield biased results for sexually inactive women due to lack of a partner,

relationship quality, or reasons unrelated to cancer treatment effects [17, 26]. To mitigate this, we randomised participants with stratification based on partner status, and included the

response option ‘not applicable, no partner’ for items concerning the partner relationship, thereby minimising potential imbalance in the study outcomes. It is also possible that sexual

functioning may further improve on the longer term. To investigate potential further recovery and to assess if the high rates of sexual activity will be sustained over time, a long-term

evaluation at 24 months after radiotherapy was added per protocol amendment and results will be available next year. Finally, it could be argued that this study attracted relatively young

and motivated participants, and that the improvement in vaginal and sexual functioning in both study groups was due to recovery over time. However, prospective studies involving cohorts of

women treated with radio(chemo)therapy and brachytherapy for advanced or recurrent cervical cancer, without any standard sexual rehabilitation care, reported clearly higher prevalence rates

of feelings of vaginal shortness, dryness and pain during sexual activity, vaginal stenosis and lower compliance with dilator use [4, 7, 8, 27, 28]. The prospective EMBRACE vaginal morbidity

sub-study, which recommended sexual rehabilitation counselling after treatment, along with clear instructions on dilator use, demonstrated similar outcomes to our study regarding stenosis

(physician-reported), vaginal shortness, dryness, and dyspareunia (patient-reported) [29]. Half of sexually active women reported feelings of vaginal shortness, dryness, and

intercourse-related pain, which was also the case in our study cohort, although in vast majority rated as ‘a little’. However, in the EMBRACE vaginal morbidity sub-study cohort 54% reported

to be sexually active at 12 months, while this was ~70% in the SPARC trial, possibly reflecting the effects of the increased patient education and awareness on early sexual rehabilitation.

Regarding vaginal stenosis, either no or only mild stenosis was found at 12 months in both study cohorts, probably resulting from the improved radiotherapy and brachytherapy techniques

causing less severe vaginal effects than in historical cohorts [30] along with more frequent vaginal dilation reported by the participants. In the SPARC trial, 85% (intervention) versus 75%

(care-as-usual) of women who received brachytherapy, reported using any form of dilation at least twice a week at 12 months, indicating high compliance. The results of the SPARC trial

highlight the improved sexual rehabilitation care for women undergoing intensive radio(chemo)therapy and brachytherapy in the Netherlands, both before and during the study period,

emphasising the importance of awareness, education and comprehensive care. This may have resulted in comparable sexual rehabilitation for both study groups. We therefore regard this

care-as-usual approach as best practice to improve sexuality and thus quality-of-life after gynaecological cancer treatment. This approach encompasses thorough patient information, as well

as a sexual rehabilitation appointment with a specifically trained dedicated nurse at 1 month post-radiotherapy, including explicit guidance on dilator use and coaching on resuming sexual

activities for women who underwent radiotherapy combined with brachytherapy, and dedicated follow-up regarding sexual functioning and dilator use over the first year after completion of

treatment. DATA AVAILABILITY All (Dutch) materials, such as information booklets and the treatment protocol, will be available by the end of the current study after the publication of the

results. Data containing potentially identifying or sensitive patient information are restricted according to European law (General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR)). The datasets generated

and/or analysed during the current study are not available in a public repository but are available upon reasonable request after evaluation of a dedicated study protocol via MtK

([email protected]). REFERENCES * Pieterse QD, Kenter GG, Maas CP, de Kroon CD, Creutzberg CL, Trimbos JB, et al. Self-reported sexual, bowel and bladder function in cervical cancer

patients following different treatment modalities: longitudinal prospective cohort study. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2013;23:1717–25. https://doi.org/10.1097/IGC.0b013e3182a80a65 Article PubMed

Google Scholar * Jensen PT, Groenvold M, Klee MC, Thranov I, Petersen MA, Machin D. Longitudinal study of sexual function and vaginal changes after radiotherapy for cervical cancer. Int J

Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2003;56:937–49. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0360-3016(03)00362-6 Article PubMed Google Scholar * Abbott-Anderson K, Kwekkeboom KL. A systematic review of sexual

concerns reported by gynecological cancer survivors. Gynecologic Oncol. 2012;124:477–89. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ygyno.2011.11.030 Article Google Scholar * Kirchheiner K, Smet S,

Jurgenliemk-Schulz IM, Haie-Meder C, Chargari C, Lindegaard JC, et al. Impact of vaginal symptoms and hormonal replacement therapy on sexual outcomes after definitive chemoradiotherapy in

patients with locally advanced cervical cancer: results from the EMBRACE-I study. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2022;112:400–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijrobp.2021.08.036 Article PubMed

Google Scholar * Roussin M, Lowe J, Hamilton A, Martin L. Factors of sexual quality of life in gynaecological cancers: a systematic literature review. Arch Gynecol Obstet.

2021;304:791–805. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00404-021-06056-0 Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Damast S, Jeffery DD, Son CH, Hasan Y, Carter J, Lindau ST, et al. Literature

review of vaginal stenosis and dilator use in radiation oncology. Practical Radiat Oncol. 2019;9:479–91. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.prro.2019.07.001 Article Google Scholar * Robinson JW,

Faris PD, Scott CB. Psychoeducational group increases vaginal dilation for younger women and reduces sexual fears for women of all ages with gynecological carcinoma treated with

radiotherapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1999;44:497–506. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0360-3016(99)00048-6 Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Bakker RM, Vermeer WM, Creutzberg CL, Mens

JWM, Nout RA, ter Kuile MM. Qualitative accounts of patients’ determinants of vaginal dilator use after pelvic radiotherapy. J Sex Med. 2015;12:764–73. https://doi.org/10.1111/jsm.12776

Article PubMed Google Scholar * Hanlon A, Small W Jr, Strauss J, Lin LL, Hanisch L, Huang L, et al. Dilator use after vaginal brachytherapy for endometrial cancer: a randomized

feasibility and adherence study. Cancer Nurs. 2018;41:200–9. https://doi.org/10.1097/NCC.0000000000000500 Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Kozak MM, Usoz M, Fujimoto D, von

Eyben R, Kidd E. Prospective randomized trial of email and/or telephone reminders to enhance vaginal dilator compliance in patients undergoing brachytherapy for gynecologic malignancies.

Brachytherapy. 2021;20:788–95. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brachy.2021.03.010 Article PubMed Google Scholar * Flynn P, Kew F, Kisely SR. Interventions for psychosexual dysfunction in women

treated for gynaecological malignancy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009;2009:CD004708 https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD004708.pub2 Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar *

Huffman LB, Hartenbach EM, Carter J, Rash JK, Kushner DM. Maintaining sexual health throughout gynecologic cancer survivorship: a comprehensive review and clinical guide. Gynecol Oncol.

2016;140:359–68. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ygyno.2015.11.010 Article PubMed Google Scholar * Scott JL, Halford WK, Ward BG. United we stand? The effects of a couple-coping intervention on

adjustment to early stage breast or gynecological cancer. J Consult Clin Psych. 2004;72:1122–35. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-006x.72.6.1122 Article Google Scholar * Bakker RM, Mens JW,

de Groot HE, Tuijnman-Raasveld CC, Braat C, Hompus WC, et al. A nurse-led sexual rehabilitation intervention after radiotherapy for gynecological cancer. Support Care Cancer. 2017;25:729–37.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-016-3453-2 Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Suvaal I, Hummel SB, Mens JM, van Doorn HC, van den Hout WB, Creutzberg CL, et al. A sexual rehabilitation

intervention for women with gynaecological cancer receiving radiotherapy (SPARC study): design of a multicentre randomized controlled trial. BMC Cancer. 2021;21:1295

https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-021-08991-2 Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Rakovshik SG, McManus F, Vazquez-Montes M, Muse K, Ougrin D. Is supervision necessary?

Examining the effects of internet-based CBT training with and without supervision. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2016;84:191–9. https://doi.org/10.1037/ccp0000079 Article PubMed Google Scholar

* Rosen R, Brown C, Heiman J, Leiblum S, Meston C, Shabsigh R, et al. The Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI): a multidimensional self-report instrument for the assessment of female sexual

function. J Sex Marital Ther. 2000;26:191–208. https://doi.org/10.1080/009262300278597 Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Wiegel M, Meston C, Rosen R. The female sexual function index

(FSFI): cross-validation and development of clinical cutoff scores. J Sex Marital Ther. 2005;31:1–20. https://doi.org/10.1080/00926230590475206 Article PubMed Google Scholar * Derogatis

LR, Rosen R, Leiblum S, Burnett A, Heiman J. The Female Sexual Distress Scale (FSDS): initial validation of a standardized scale for assessment of sexually related personal distress in

women. J Sex Marital Ther. 2002;28:317–30. https://doi.org/10.1080/00926230290001448 Article PubMed Google Scholar * Greimel ER, Kuljanic Vlasic K, Waldenstrom AC, Duric VM, Jensen PT,

Singer S, et al. The European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) quality-of-life questionnaire cervical cancer module: EORTC QLQ-CX24. Cancer. 2006;107:1812–22.

https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.22217 Article PubMed Google Scholar * Cohen J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. 2nd edn. Mahwah, New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum

Associates, Inc.; 1988. * Rizopoulos D. GLMMadaptive: generalized linear mixed models using Adaptive Gaussian quadrature. R package version 0.8-2. 2021 [cited 2022 1st of June]. Available

from: https://drizopoulos.github.io/GLMMadaptive/. * Dutch Patient Advocacy Group (Olijf). Living with cancer - Sexuality 2021 [cited 2024 May 26]. Available from:

https://olijf.nl/leven-met-kanker/seksualiteit. * Reed N, Balega J, Barwick T, Buckley L, Burton K, Eminowicz G, et al. British Gynaecological Cancer Society (BGCS) cervical cancer

guidelines: recommendations for practice. Eur J Obstet Gyn R B. 2021;256:433–65. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejogrb.2020.08.020 Article Google Scholar * Integraal Kankercentrum Nederland.

Cervixcarcinoom Landelijke richtlijn, Versie: 3.0 2012 [cited 2020 7th of December]. Available from:

http://www.med-info.nl/Richtlijnen/Oncologie/Gynaecologische%20tumoren/Cervixcarcinoom.pdf. * Meyer-Bahlburg HFL, Dolezal C. The female sexual function index: a methodological critique and

suggestions for improvement. J Sex Marital Ther. 2007;33:217–24. https://doi.org/10.1080/00926230701267852 Article PubMed Google Scholar * Kirchheiner K, Potter R, Tanderup K, Lindegaard

JC, Haie-Meder C, Petric P, et al. Health-related quality of life in locally advanced cervical cancer patients after definitive chemoradiation therapy including image guided adaptive

brachytherapy: an analysis from the EMBRACE study. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2016;94:1088–98. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijrobp.2015.12.363 Article PubMed Google Scholar * Jensen PT,

Froeding LP. Pelvic radiotherapy and sexual function in women. Transl Androl Urol. 2015;4:186–205. https://doi.org/10.3978/j.issn.2223-4683.2015.04.06 Article PubMed PubMed Central Google

Scholar * Suvaal I, Kirchheiner K, Nout RA, Sturdza AE, Van Limbergen E, Lindegaard JC, et al. Vaginal changes, sexual functioning and distress of women with locally advanced cervical

cancer treated in the EMBRACE vaginal morbidity substudy. Gynecol Oncol. 2023;170:123–32. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ygyno.2023.01.005 Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Kirchheiner K,

Nout RA, Lindegaard JC, Haie-Meder C, Mahantshetty U, Segedin B, et al. Dose-effect relationship and risk factors for vaginal stenosis after definitive radio(chemo)therapy with image-guided

brachytherapy for locally advanced cervical cancer in the EMBRACE study. Radiother Oncol. 2016;118:160–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.radonc.2015.12.025 Article PubMed Google Scholar

Download references ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The SPARC study was supported by a grant from the Dutch Cancer Society, Alpe d’HuZes fund (grant number 10674). We thank the patients and their families

who participated in this trial and contributed their time and efforts to complete the many questionnaires. We are indebted to the oncology nurses, brachytherapy technicians, radiotherapy

medical assistants, supervisors, and multidisciplinary clinical research teams at the participating centres. We express our gratitude to the independent panel for their efforts in assessing

the adherence to the treatment protocol, as well as evaluating the competency of the trained nurses. The patient advocacy group for gynaecological cancers Olijf provided information at their

website and provided input before and during the course of the study [23]. This study was presented in part at the International Psycho-Oncology Society World Congress (Milan, Italy, August

31–September 3 2023). FUNDING The SPARC trial was supported by a grant from the Dutch Cancer Society/ Alpe d’HuZes fund (grant 10674). The funding body had no role in study design, data

collection, data interpretation, data analysis or writing of this report. AUTHOR INFORMATION AUTHORS AND AFFILIATIONS * Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Leiden University Medical

Center, Leiden, The Netherlands Isabelle Suvaal, Susanna B. Hummel, Charlotte C. Tuijnman-Raasveld, Cor D. de Kroon & Moniek M. ter Kuile * Department of Radiotherapy, Erasmus MC Cancer

Institute, University Medical Center Rotterdam, Rotterdam, The Netherlands Jan-Willem M. Mens & Remi A. Nout * Department of Biomedical Data Sciences, Leiden University Medical Center,

Leiden, The Netherlands Roula Tsonaka & Wilbert B. van den Hout * Department of Radiation Oncology, Leiden University Medical Center, Leiden, The Netherlands Laura A. Velema & Carien

L. Creutzberg * Department of Radiation Oncology, Amsterdam UMC Location University of Amsterdam, Amsterdam, The Netherlands Henrike Westerveld * Department of Radiation Oncology, Catharina

Hospital, Eindhoven, The Netherlands Jeltsje S. Cnossen * Department of Radiation Oncology, Radboudumc, Nijmegen, The Netherlands An Snyers * Department of Radiation Oncology, University

Medical Center Utrecht, Utrecht, The Netherlands Ina M. Jürgenliemk-Schulz * Department of Radiation Oncology, Maastro, Maastricht, The Netherlands Ludy C. H. W. Lutgens * Department of

Radiation Oncology, University Medical Center Groningen, Groningen, The Netherlands Jannet C. Beukema * Department of Radiation Oncology, Radiotherapiegroep, Arnhem, The Netherlands Marie A.

D. Haverkort * Department of Radiation Oncology, The Netherlands Cancer Institute, Amsterdam, The Netherlands Marlies E. Nowee * Department of Gynaecology, Erasmus MC, University Medical

Center Rotterdam, Rotterdam, The Netherlands Helena C. van Doorn Authors * Isabelle Suvaal View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Susanna B.

Hummel View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Jan-Willem M. Mens View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google

Scholar * Charlotte C. Tuijnman-Raasveld View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Roula Tsonaka View author publications You can also search for

this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Laura A. Velema View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Henrike Westerveld View author publications You

can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Jeltsje S. Cnossen View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * An Snyers View author

publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Ina M. Jürgenliemk-Schulz View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar *

Ludy C. H. W. Lutgens View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Jannet C. Beukema View author publications You can also search for this author

inPubMed Google Scholar * Marie A. D. Haverkort View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Marlies E. Nowee View author publications You can also

search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Remi A. Nout View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Cor D. de Kroon View author publications

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Wilbert B. van den Hout View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Carien L.

Creutzberg View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Helena C. van Doorn View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed

Google Scholar * Moniek M. ter Kuile View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar CONTRIBUTIONS IS was the principal investigator of the study, was

responsible for the conceptualisation, investigation, resources, methodology, and writing of the original draft, and was involved in data curation, project administration, formal analysis,

and visualisation. SH was involved in data curation, project administration, and methodology, and was responsible for conceptualisation, investigation, and resources. JWM was involved in

funding acquisition, and responsible for conceptualisation, investigation, and resources. CTR was responsible for conceptualisation, investigation, and resources, and involved in

methodology. RT was involved in formal analysis. LV was involved in investigation and resources. HW was involved in investigation and resources. JC was involved in investigation and

resources. AS was involved in investigation and resources. IJS was involved in investigation and resources. LL was involved in investigation and resources. JB was involved in investigation

and resources. MH was involved in investigation and resources. MN was involved in investigation and resources. RN was involved in conceptualisation. CdK was involved in conceptualisation.

WvdH was involved in conceptualisation. CC was the principal investigator of the study, was responsible for the conceptualisation, investigation, resources, methodology, writing of the

original draft, and was involved in funding acquisition, and supervision. HvD was responsible for conceptualisation, investigation, and resources, and involved in methodology. MtK was the

principal investigator of the study, was responsible for the conceptualisation, investigation, resources, methodology, and writing of the original draft, and was involved in the formal

analysis, in funding acquisition, project administration, and supervision. All authors were involved in writing, reviewing, and editing the manuscript. The principal investigators (IS, MtK,

CC), the associated investigator (SH), and the trial statistician (RT) had full access to the study data. The decision to submit for publication was made after discussion within the trial

management group. The principal investigators had final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication. CORRESPONDING AUTHOR Correspondence to Moniek M. ter Kuile. ETHICS

DECLARATIONS COMPETING INTERESTS The authors declare no competing interests. ETHICS APPROVAL AND CONSENT TO PARTICIPATE The protocol was approved by the Scientific Review Board of the Dutch

Cancer Society, by the Medical Ethics Committee Leiden-Den Haag-Delft (number NL62767.058.17), and by the Institutional Review Boards and/or Ethics Committees of the participating centres.

All participating women provided written informed consent. The study was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. CONSENT FOR PUBLICATION Not applicable. ADDITIONAL

INFORMATION PUBLISHER’S NOTE Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION SUPPLEMENTARY

MATERIALS APPENDIX 1-6 SPARC-TRIAL RIGHTS AND PERMISSIONS OPEN ACCESS This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing,

adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons

licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a

credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted

use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. Reprints and permissions ABOUT

THIS ARTICLE CITE THIS ARTICLE Suvaal, I., Hummel, S.B., Mens, JW.M. _et al._ Efficacy of a nurse-led sexual rehabilitation intervention for women with gynaecological cancers receiving

radiotherapy: results of a randomised trial. _Br J Cancer_ 131, 808–819 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41416-024-02775-8 Download citation * Received: 24 April 2024 * Revised: 13 June 2024

* Accepted: 18 June 2024 * Published: 03 July 2024 * Issue Date: 21 September 2024 * DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41416-024-02775-8 SHARE THIS ARTICLE Anyone you share the following link

with will be able to read this content: Get shareable link Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article. Copy to clipboard Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt

content-sharing initiative