Mettl3 regulates wtap protein homeostasis

- Select a language for the TTS:

- UK English Female

- UK English Male

- US English Female

- US English Male

- Australian Female

- Australian Male

- Language selected: (auto detect) - EN

Play all audios:

ABSTRACT The Wilms tumor 1 (WT1)-associated protein (WTAP) is upregulated in many tumors, including, acute myeloid leukemia (AML), where it plays an oncogenic role by interacting with

different proteins involved in RNA processing and cell proliferation. In addition, WTAP is also a regulator of the nuclear complex required for the deposition of _N_6-methyladenosine (m6A)

into mRNAs, containing the METTL3 methyltransferase. However, it is not clear if WTAP may have m6A-independent regulatory functions that might contribute to its oncogenic role. Here, we show

that both knockdown and overexpression of METTL3 protein results in WTAP protein upregulation, indicating that METTL3 levels are critical for WTAP protein homeostasis. However, we show that

WTAP upregulation is not sufficient to promote cell proliferation in the absence of a functional METTL3. Therein, these data indicate that the reported oncogenic function of WTAP is

strictly connected to a functional m6A methylation complex. SIMILAR CONTENT BEING VIEWED BY OTHERS THE M6A READER IGF2BP3 PROMOTES ACUTE MYELOID LEUKEMIA PROGRESSION BY ENHANCING RCC2

STABILITY Article Open access 25 February 2022 METTL13 IS ESSENTIAL FOR THE SURVIVAL OF ACUTE MYELOID LEUKEMIA CELLS BY REGULATING MYC Article Open access 17 May 2025 HIF1Α-MEDIATED

TRANSACTIVATION OF WTAP PROMOTES AML CELL PROLIFERATION VIA M6A-DEPENDENT STABILIZATION OF KDM4B MRNA Article 22 April 2023 INTRODUCTION _N_6-methyladenosine (m6A) is the most abundant

internal chemical modification in eukaryotic mRNA and it can control any aspect of mRNA post-transcriptional regulation1. In mammals, the writer of m6A is a nuclear multicomponent complex

composed of two _methyltransferase-like_ proteins, METTL3 and METTL14, and the regulatory proteins _Wilms tumor 1-associated protein_ (WTAP), _vir like m6A methyltransferase associated_

(VIRMA, also known as KIAA1429), _RNA-binding motif protein 15_ (RBM15) and _zinc finger CCCH-type containing 13_ (ZC3H13)1, 2. METTL3 is the sole catalytic component of the complex while

METTL14 functions in structural stabilization and RNA substrate recognition3,4,5. More recently, the human U6 snRNA m6A methyltransferase METTL16 has been shown to target intronic regions of

pre-mRNAs and lncRNAs6, 7. Removal of m6A from transcripts occurs predominantly in the nucleus and requires the activity of the _alkB homologue 5 protein_ (ALKBH5) and _fat mass and

obesity-associated protein_ (FTO)1. Several proteins, in both nucleus and cytoplasm, can read m6A modification and, eventually, regulate different phases of mRNA expression8. In particular,

proteins containing the YTH domain were the first to be identified as m6A-specific “readers”. Notably, METTL3 itself can switch from writer to reader by moving in the cytoplasm where it can

regulate the translation of specific mRNAs by direct binding to RNA and recruitment of eIF39, 10. The WTAP protein has been recently described as an oncogenic protein in different cancers,

including acute myeloid leukemia (AML)11. WTAP was initially identified as an interactor of the Wilms Tumor-1 (WT-1) protein12, a zinc-finger protein that can act as both transcriptional and

splicing regulator. Later on, WTAP was shown to form stable interactions with the Hakai protein (also known as CBLL1), a C3HC4-type RING finger containing E3 ubiquitin ligase whose

expression is correlated to cell proliferation and tumorigenesis13, and different proteins involved in regulation of RNA processing and translation, including METTL314. Interestingly, even

if a large proportion of mRNAs associated with WTAP is also bound by METTL3, there are many mRNAs that are specifically associated with only one of the two proteins and upon knockdown only

half of the misregulated genes are in common between the two factors15. Moreover, it has been proposed that WTAP form a stable complex with Virma, Hakai, Rbm15, and Zc3h13 (referred to as

MACOM, _m_6A-METTL-_a_ssociated _com_plex) that acts beyond m6A methylation2. Thus, it is not clear if WTAP may have independent regulatory functions from the m6A modification complex that

might contribute to its oncogenic role. Here, we show that both the knockdown and overexpression of METTL3 protein results in WTAP upregulation, indicating that METTL3 levels are critical

for WTAP protein homeostasis. In particular, we demonstrate that METTL3 levels may regulate WTAP expression at multiple levels by direct and indirect mechanisms that include mRNA translation

and stability. However, we show that WTAP upregulation has on oncogenic effect only in the presence of a functional METTL3. RESULTS AND DISCUSSION To get insight into a potential role of

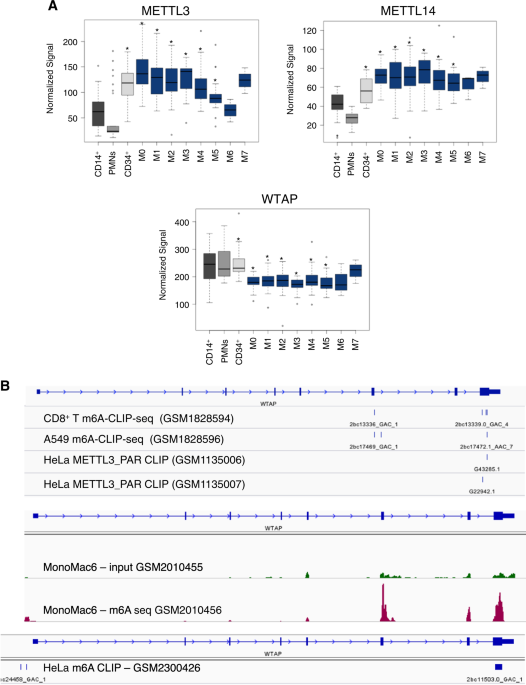

the m6A methylation complex in AML, we first analyzed the expression of its components in a variety of AML subtypes, normal hematopoietic progenitor cells and mature myeloid cells (data from

GEO and the Cancer Genome Atlas databases, TCGA). METTL3 and METTL14 mRNAs are significantly up-regulated in a high percentage of different AML FAB subtypes (the French–American–British

classification of AML) compared to mature myeloid cells, while both genes are highly expressed in CD34+ progenitor cells (Fig. 1a and Supplemental Figure S1). The lack of significance in M6

and M7 AMLs is very likely due to the small number of samples. Moreover, it has been reported that both METTL3 and METTL14 are also highly expressed in AML compared to other cancers16. While

our studies were in progress, different independent studies reported similar results showing a specific up-regulation of METTL3 and METTL14 in AML cells and a critical role for these

proteins in AML cells survival and differentiation17,18,19,20. On the other hand, we observed low expression of WTAP mRNA despite the high levels of WTAP protein reported in AML11. By

analyzing published m6A-seq and m6A-CLIP experiments performed in different cell lines17, 21,22,23, including the AML cell line MonoMac6, we observed that WTAP mRNA is generally m6A

methylated in exon 6 and in exon 8 (Fig. 1b). Furthermore, published PAR-CLIP data revealed binding of METTL3 within the m6A peak in the exon 8 of WTAP mRNA (Fig. 1b)22. We checked for

METTL3, METTL14 and WTAP localization in several AML cell lines, and in all of them we detected METTL3 mislocalization in the cytoplasm while the other components of the m6A methylation

complex were predominantly localized in the nuclear fraction (Fig. 2a). Therein, in view of these results, we hypothesized that METTL3 might contribute to the WTAP aberrant up-regulation

observed in AML. By using K562 leukemia cells stably expressing a doxycycline (dox) inducible METTL3 or METTL3 catalytic inactive mutant (aa395–398, DPPW → APPA, METTL3 APPA), we showed that

METTL3 overexpression (48 h dox) resulted in increased levels of WTAP protein without concomitant increase in WTAP mRNA levels (Fig. 2b, c). Notably, METTL3 positively controls WTAP protein

levels regardless its catalytic activity, similar to what has been shown for the translational control mediated by cytoplasmic METTL3 in lung cancer9. Binding of METTL3 and METTL3 APPA to

WTAP mRNA in cytoplasm of K562 cells was confirmed by CLIP experiments using stable cell lines carrying inducible FLAG-tagged expression cassettes (Fig. 2d). The METTL3 cytoplasmic mRNA

target encoding for TAZ9 was utilized as positive control. Altogether these data showed that WTAP mRNA is m6A methylated and bound by cytoplasmic METTL3. To analyze if the observed phenotype

was specific of AML cells, we transfected HeLa cells with a plasmid for transient expression of a FLAG-tagged WTAP construct containing only WTAP coding sequence together with plasmids

expressing a GFP control, METTL3 or METTL3 APPA (Fig. 3a, b). Also in this case, we observed increased expression of FLAG-WTAP protein without concomitant increase of FLAG-WTAP mRNA

expression. It has been recently shown that METTL3 can bind m6A containing mRNAs10. We therefore examined whether m6A modifications in WTAP mRNA are necessary for METTL3 binding. We

transfected a FLAG-tagged WTAP construct with a deletion in the region of exon 8 (FLAG-WTAP_Δ8), containing the m6A modifications, together with plasmids for METTL3 expression or control GFP

(Supplementary Figure S2). The construct was already devoid of 5′- and 3′-UTR. Notably, we still observed increased WTAP protein levels and binding of METTL3 protein to WTAP mRNA. Moreover,

binding of METTL3 and METTL3 APPA to FLAG-WRAP_Δ8 in cytoplasm of transfected cells was confirmed by CLIP experiments. These findings indicate that m6A modifications in WTAP mRNA are not

required for METTL3 association. In order to understand if the increase of WTAP protein depends on translation or protein stabilization, we performed overexpression of METTL3 protein in the

presence of the translation elongation inhibitor cycloheximide (Fig. 3c). Thus, we co-transfected HeLa cells with the FLAG-tagged WTAP construct (see above) together with a plasmid

expressing the wild type METTL3 protein, METTL3 APPA or control GFP. After 48 h from transfection we treated cells with cycloheximide for 4 h (+CHX). We used non-treated cells as control

cells (−CHX). Properly occurred translational block was verified by checking the level of p27 protein, a well-known short half-life protein in proliferating cells24. In contrast, Actinin

(ACTN1) protein levels were found to be constant throughout the experiment, thus it was utilized as endogenous control. Interestingly, we observed that after cycloheximide treatment WTAP

protein decreased at the same levels in cells expressing METTL3 constructs and control GFP (Fig. 3c), indicating that the observed increased of WTAP in the control cells is not merely due to

protein stabilization. In view of the reported activity of cytoplasmic METTL3 on mRNA translation9, we performed a polysome profiling by sucrose gradient centrifugation from cytoplasmic

extracts prepared from control (GFP) or METTL3 (METTL3 and METTL3-APPA) stably expressing K562 cells and transiently transfected HeLa cells (Figs. 4 and 5). Similar to what we observed on

K562, in HeLa cells the endogenous WTAP protein displayed an increase expression in both METTL3 and METTL3 APPA overexpression compared to GFP (Fig. 5). Again, the protein increase is not

accompanied by WTAP mRNA upregulation. Then, we extracted RNA from the fractions adding an equal amount of RNA spike-in to each of them for normalization and analyzed WTAP mRNA distribution

in pooled fractions representing heavy-polysomes (fractions 1–3), light-polysomes (fractions 4–6), 80S (fractions 7–9) and free-mRNAs (fractions 10–12). Then, we performed qRT-PCR on WTAP

and a control mRNA, ActB (Figs. 4a,b and 5c, d). Importantly, upon overexpression of METTL3 and METTL3-APPA we observed an increase of WTAP mRNA in the polysomal fractions associated with a

decrease from the free RNA fractions. Moreover, analysis by Western blot revealed that, similarly to the translation initiation factor eIF3a, METTL3 was detected with 80S and light polysomal

fractions (Figs. 4c and 5e). Thus, we can conclude that METTL3 affects WTAP protein levels through translation regulation mechanisms even if, in view of the light shift into polysomal

fractions, it is possible also a contribution from protein stabilization. In order to further investigate the relationship between METTL3 and WTAP expression, we analyzed WTAP levels upon

knock down of METTL3 by using two different lentiviral vectors expressing dox-inducible shRNA in K562 cells. A non-targeting scramble shRNA was utilized as control (shSCR). Interestingly,

upon METTL3 downregulation we observed an increase of both WTAP mRNA and protein levels (Fig. 6a, b). Analysis of WTAP pre-mRNA levels showed that they did not increase concomitantly with

WTAP mRNA and METTL3 downregulation, indicating that the increase of WTAP mRNA is not due to transcriptional regulation (Fig. 6c). Altogether these data indicate that both up- and down-

regulation of METTL3 levels result in an increase of WTAP protein and, therein, that this is not merely due to protein stabilization by METTL3 interaction. METTL3 depletion by shRNAs

resulted in an inhibition of cell proliferation. However, we did not observe a significant induction of apoptosis as reported in other AML cell lines (Supplemental Figure S3). These data

indicate that the increase of WTAP protein upon METTL3 knock down is not sufficient to promote cell growth. Notably, the increase of WTAP proteins preceded the arrest in proliferation and

was not observed upon cell cycle arrest of K562 induced by imatinib, a tyrosine kinase inhibitor that specifically induces cell cycle arrest and apoptosis in K562 cell (Supplementary Figure

S4), indicating that is specifically due to METTL3 downregulation and not to a general decrease in cell proliferation. m6A IP followed by qRT-PCR using primers to amplify the m6A peak region

(exon 8) of fragmented WTAP mRNA was used to analyze the m6A methylation of WTAP mRNA in K562 AML cells. Experiments were performed 6 days after dox induction. As expected, we observed

immunoprecipitation of WTAP exon 8 in control cells and a strong decrease upon METTL3 knockdown (Fig. 6d). Furthermore, the enhanced expression of WTAP mRNA coincides with the loss of m6A

modifications. Therein, suggesting that the observed increase in WTAP it is dependent on the loss of m6A from its mRNA. We knocked-down the m6A reader YTHDF2, which destabilizes m6A

containing mRNAs, but we did not observe an increased expression of WTAP mRNA and protein (Supplemental Figure S5). The identification of the factor(s) responsible for the modulation of WTAP

expression upon METTL3 knockdown will be subject of further investigation. In conclusion, we show that METTL3 protein levels are important for WTAP protein homeostasis. In particular, we

demonstrate that METTL3 can increase WTAP expression by at least two independent mechanisms (Fig. 7). First, increase of METTL3 levels can produce higher WTAP protein levels, which are

independent from METTL3 catalytic activity and relies on increase WTAP mRNA translation and protein stabilization. This mechanism is relevant to increase WTAP expression concomitantly to the

METTL3/METTL14 core complex and sustain the oncogenic role reported for the m6A modification complex in leukemia. Second, decrease of METTL3 levels results in increased WTAP mRNA levels

and, eventually, WTAP protein. However, in the absence of a functional METTL3 the observed increase of WTAP protein is not sufficient to promote cell growth. Therein, these data indicate

that the reported oncogenic function of WTAP is strictly connected to a functional m6A methylation complex. MATERIALS AND METHODS CELL CULTURE AND REAGENTS K562 cell lines were cultured at

37 °C under an atmosphere containing 5% CO2 in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 1× penicillin/streptomycin solution, 1× L-glutamine, and 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS). HeLa cells were grown

in DMEM medium with 10% FBS, 1× L-glutamine, 1× penicillin–streptomycin and cultured at 37 °C under an atmosphere containing 5% CO2. Doxycycline (Dox), cycloheximide and Imatinib mesylate

were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. PLASMID CONSTRUCTS AND CELL LINES The METTL3 and WTAP DNA was amplified from K562 cDNA and cloned Hind III and Not I, and BamH I and Not I, respectively,

in pcDNA3.1 vector with primers METTL3_HindIII_FW and METTL3_NotI_REV, and WTAP_BamHI_FW and WTAP_NotI_REV. METTL3 APPA mutant was obtained by reverse PCR with primers APPA_mettl3_FW and

APPA_mettl3_REV. FLAG peptide sequence was introduced upstream the coding sequence of METTL3 and WTAP constructs by reverse PCR with primers METTL3_flag_FW and METTL3_flag_rev for METTL3

plasmid, and WTAP_flag_FW and WTAP_flag_rev for WTAP plasmid. FLAG WTAP Δ8 plasmid was obtained by reverse PCR on the plasmid pcDNA3.1 FLAG WTAP with primers WTAP_m6Adel_iPCR_REV and

WTAP_pcDNA_FW. FLAG-METTL3 constructs were subcloned in the enhanced PiggyBac (ePB) vector ePB-PURO for stable integration25. This plasmid contains a TET-on system for inducible transgene

expression. Helper and transposon plasmids were electroporated in K562 with Lipofectamine 2000 reagent (Invitrogen) according to manufacturer instruction. Selection with 1 μg/ml of puromycin

(SIGMA) was initiated 2 days after transfection and maintained until resistant colonies became visible. Induction was obtained with dox at a concentration of 50 ng/ml. HeLa cells were

transfected with pcDNA 3.1 vectors using Lipofectamine 2000 Reagent (Invitrogen) according to manufacturer instruction. For METTL3 downregulation in K562 cells we have utilized an inducible

shRNA expression system based on the lentiviral vector pLKO-Tet-On26. Inducible constructs were derived from Mission Lentiviral shRNA clones (Sigma-Aldrich) TRCN0000289812 (shMETTL3_1),

TRCN0000289814 (shMETTL3_2) and SHC202 TRC2 (Non-Target shRNA Control) as described26. Selection with 1 μg/ml of puromycin (Sigma-Aldrich) was initiated 2 days after transduction and

maintained until resistant colonies became visible. After selection, shRNAs induction was obtained with dox at a concentration of 50 ng/ml. SiRNAs against YTHDF2 mRNA (Qiagen SI04174534),

METTL3 (Qiagen SI04340749, SI04241265, SI04140038, SI04317096) and control siRNAs (Qiagen Negative control 1027281) were transfected in a final concentration of 30 nM using Lipofectamine

RNAiMAX (Invitrogen) according to manufacturer instruction. CELLULAR MORTALITY Cell death was analyzed by flow cytometry (CyAN ADP DAKO) with propidium iodide (PI) exclusion assay after

staining the cells with 2.5 μg/ml of PI (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA). LENTIVIRUS PACKAGING AND VIRAL TRANSDUCTION Lentiviral particles were produced by calcium phosphate transient

transfection of 293T cells, cotransfecting the specific lentiviral plasmid (pLKO-Tet-On shSCR, pLKO-Tet-On shMETTL3_1 and pLKO-Tet-On shMETTL3_2) together with the packaging plasmids (pLP1

and pLP2) and the envelope plasmid pLP/VSVG encoding for VSV-G protein. One 150 mm dish of 293T cells was transfected for each lentiviral construct. The calcium phosphate–DNA precipitate was

allowed to stay on the cells for 14–16 h, after which the medium was replaced with complete media supplemented with 1 mM sodium butyrate (SIGMA-ALDRICH). The medium was collected 48 h after

transfection, replaced with complete media supplemented with sodium butyrate 1 mM and again collected 72 h after transfection. Collected media were pulled, centrifuged at 1000 rpm for 5 min

at room temperature, filtered through 0.45 μm pore nitrocellulose filters and then ultracentrifuged at 20,000 rpm for 2 h at 4 °C with SW28 rotor (Beckman Coulter). The supernatant was then

removed while the pellet containing lentiviral particles was resuspended in 25 μl HBSS buffer (GIBCO ThermoFisher) and stored at −80 °C. For viral transduction, 500.000 K562 cells were

resuspended in 500 μl of serum-free and antibiotic-free media supplemented with 4 µg/ml Polybrene (SIGMA-ALDRICH). Cells were then infected with 5 μl of the lentiviral particles previously

resuspended in HBSS buffer. After 6 h, one volume of medium with serum 2× and antibiotic 2× was added. 24 h after viral transduction the medium was replaced with complete medium. 48 h after

viral transduction cells were selected with 1.5 µg/ml of puromycin (SIGMA-ALDRICH) until resistant colonies became visible (3–5 days). PROTEIN STABILITY ASSAY After 48 h from transient

transfection, Hela cells were treated with 100 μg/ml of cycloheximide for 4 h. We used non-treated cells as control cells. Cells were than collected and protein fraction was analyzed.

Notably, we analyzed protein levels by western blot using equal volumes of different samples. RNA EXTRACTION AND REAL-TIME QRT-PCR ANALYSIS Total RNA was extracted using the Quick RNA

miniprep kit (Zymo) according to manufacturer instructions. For mRNA analysis, reverse transcription to cDNA was performed with the SuperScript VILO cDNA Synthesis Kit (Life Technologies)

according to the manufacturer instructions. Quantitative real-time PCR was performed on an Applied Biosystems 7500 Fast Real Time PCR System. Reactions were performed in triplicate using the

SYBR green dye detection system and analyzed using 7500 Software v2.0.6 (Applied Biosystems). Relative expression levels of targets were determined using the comparative 2∆∆Ct method. ActB

mRNA was utilized as a reference (primers: ACTB_hs_FW, ACTB_hs_REV). METTL3 was analyzed with oligos METTL3 SYBR FW and METTL3 SYBR REV, WTAP with WTAP SYBR FW and WTAP SYBR REV, FLAG WTAP

with FLAG_FW and WTAP SYBR REV2, endogenous WTAP with WTAP_5′UTR_FW and WTAP SYBR REV2, endogenous WTAP with WTAP_5′UTR_FW and WTAP SYBR REV2, WTAP long isoform with WTAP_long_FW and

WTAP_long_REV, WTAP pre-mRNA with WTAP pre-mRNA FW and WTAP pre-mRNA REV, HPRT with HPRT SYBR FW and HPRT SYBR REV, YTHDF2 with YTHDF2 SYBR FW and YTHDF2 SYBR REV, TAZ with TAZ SYBR FW and

TAZ SYBR REV. NUCLEAR/CYTOPLASMIC FRACTIONATION For nucleus to cytoplasm separation approximately 10 × 106 cells were pelleted and washed with PBS without calcium and magnesium, then they

were resuspended in 100 μl of Buffer A (200 mM Tris HCl pH 8, 10 mM NaCl, 3 mM MgCl2, 0.1% NP40, 10% glycerol, 0.2 mM EDTA, 1 mM DTT) complemented with PIC 1× (Complete, EDTA free, Roche).

Cells were incubated on ice in Buffer A for 10′, and then centrifuged at 2000 rpm for 5′ at 4 °C. The supernatant contains the cytoplasmic extract. Buffer A is added to the pellet containing

the nuclei and the resuspended pellet is centrifuged again for washing. After washing, the pellet is resuspended in Buffer C (20 mM Tris HCl pH 8, 400 mM NaCl, 20% glycerol, 1 mM DTT)

complemented with PIC 1× (Complete, EDTA free, Roche). The nuclei are subjected to thermal shock with three cycles of freezing in liquid nitrogen and thawing at 37 °C. After thermal shock

the extract is centrifuged at 13,000 rpm for 15′ at 4 °C. The supernatant contains the nuclear extract. IMMUNOBLOT ANALYSIS 30 μg of whole cell extract was separated by 10% SDS-PAGE and

electroblotted to nitrocellulose membrane (Protran, S&S). Immunoblots were incubated with antibodies Anti-FLAG M2 F3165 (Sigma-Aldrich), Anti-WTAP 60188-1-Ig (Proteintech), Anti-METTL3

[EPR18810] (Abcam), Anti-METTL14 antibody HPA038002 (Sigma Aldrich), anti-Actinin H-300 sc-15335 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), anti-GAPDH sc-25778 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), anti-YTHDF2

NBP2-31785 (Novus Biological) and anti-eIF3A ab86146 (Abcam). M6A IMMUNOPRECIPITATION m6A immunoprecipitation was performed as described in ref. 27 with a few modifications. Briefly, K562

cells infected with lentiviral vectors expressing dox-inducible shRNAs shSCR, shMETTL3_1 and shMETTL3_2 were induced with dox 50 ng/ml. 6 days after induction total RNA was extracted and

fragmented into ~100 nt long fragments in Fragmentation Buffer (100 mM Tris–HCl and 100 mM ZnCl2) for 5′ at 94 °C. Reaction was immediately blocked with addition of EDTA 50 mM. A portion of

fragmented RNA was kept as input control, while 50 μg of fragmented RNA were immunoprecipitated in 1 ml of IP Buffer (50 mM Tris–HCl, 750 mM NaCl and 0.5% Igepal CA-630) complemented with

RNasin (400 U), with 2 μg of m6A-specific antibody (ab151230, Abcam) or 2 μg of control rabbit IgG (Millipore) for 2 h of incubation at 4 °C on rotator. Then 20 μl of protein A beads

(Invitrogen), saturated with BSA (SIGMA) 0.5 μg/ml for 2 h, were added and the reaction mixtures and incubated for 2 h at 4°C on rotator. After incubation beads were spinned down and washed

three times with IP Buffer. Elution was performed incubating the beads four times in Elution Buffer (150 mM NaCl, 50 mM Tris–HCl pH 7.5, 1 mM EDTA, 0.1% SDS, 20 mM DTT) for 5′ at 42 °C.

Eluted RNA was precipitated with addition of one-tenth volumes of 3 M sodium acetate (pH 5.2), and 2.5 volumes of 100% ethanol and incubated overnight at −80 °C. Precipitated RNA was then

centrifuged at 15,000_g_ for 25′ at 4 °C and pellet resuspended in 15 μl of RNase-free water. qRT-PCR on immunoprecipitated RNA was performed with primers WTAP_long_FW and WTAP_long_REV.

CROSS-LINKING IMMUNOPRECIPITATION K562 cells stably expressing FLAG-METTL3 or FLAG-METTL3 APPA were induced with dox 50 ng/ml. 48 h after induction, cells were cross-linked in PBS at 1500 ×

100 μJ/cm2. Cells were pelleted and washed with PBS without Calcium and Magnesium, then they were resuspended in 1 ml of Buffer A (200 mM Tris HCl pH 8, 10 mM NaCl, 3 mM MgCl2, 0.1% NP40,

10% glycerol, 0.2 mM EDTA, 1 mM DTT) complemented with PIC 1× (Complete, EDTA free, Roche) and RNase Inhibitor (Invitrogen). Cell lysate was incubated on ice for 5′ and then centrifuged at

2000 rpm for 5′ at 4 °C, the supernatant contains the cytoplasmic extract. The cytoplasmic extract was brought to a higher molarity with an equal RIPA buffer 2× (NaCl 190 mM, NP40 0.9%, EDTA

0.8 mM) complemented with DTT 1 mM, PIC 1× and RNase Inhibitor 1×. 30 μl of protein G beads (Invitrogen) were washed twice with PBS-T buffer (PBS, TWEEN 0.02%) and then incubated with 7 μg

of Anti-FLAG M2 F3165 (Sigma-Aldrich) antibody or 7 μg of mouse IgG as negative control at room temperature for 1 h. Subsequently, the beads were washed twice with PBS-T buffer and incubated

at 4 °C on rotator overnight with 1.5 mg of cellular cytoplasmic extract freshly prepared. Beads were then washed with HIGH SALT WASH buffer three times (PBS 10× SIGMA diluted to have a

final concentration of 500 mM NaCl, NP-40 0.5%) complemented with PIC 1× and RNase Inhibitor. Finally, the immunoprecipitated extract was split for protein and RNA analysis. 50 μl were

denatured in Laemmli Sample Buffer (Bio-Rad) and DTT 50 mM for protein analysis by Western Blot. The RNA fraction (150 μl) was subjected to reversion of crosslinking with Proteinase K 4

mg/ml at 50 °C for 30′. Afterwards, RNA was isolated for qRT-PCR analysis and normalized on a spike-in RNA (mouse long non-coding transcript). CLIP experiments in HeLa cells were performed

using the same protocol 48 h after transient co-transfection with pcDNA3.1 METTL3 or pcDNA3.1 METTL3 APPA together with pcDNA3.1 FLAG WTAP Δ8. In this case, we utilized protein A beads

(Invitrogen) and 4 μg of Anti-METTL3 [EPR18810] (Abcam) antibody or 4 μg rabbit IgG as negative control (Millipore). POLYSOME PROFILING Cytoplasm fractionations on sucrose gradients were

performed as follows: 20 × 106 cells were lysed with 500 μl of lysis buffer (10 mM Tris pH 7.5, 100 mM NaCl, 10 mM MgCl2, 0.5% Triton X-100, and 0.5% sodium deoxycholate) supplemented with

100 mg/ml cycloheximide, 1× PIC (Complete, EDTA free, Roche) and 1× RNase guard (Thermo Scientific). The lysates were centrifuged for 5 min at 2000 rpm at 4 °C. The supernatants were

collected and centrifuged on 15–50% sucrose gradient at 37,000 rpm with a SW41 rotor (Beckman) for 2 h at 4 °C. Fractions were collected with a Bio-logic LP (Biorad). 35 μl of each fraction

were pooled together 3 by 3 obtaining four fractions (Heavy Polysomes, Light Polysomes, 80 S, Free RNA). 900 μl of Qiazol (Qiagen) was added to each 100 μl fraction and 1 pg of spike in RNA

(mouse long non-coding transcript) was added to each extraction for further normalization. RNA was extracted using RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen) according to manufacturer instruction. DATA AND

STATISTICAL ANALYSIS Microarray data were downloaded from The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA): TCGA_LAML dataset; and Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO): GSE12662, GSE19429, GSE12662, GSE16020,

GSE16837, GSE37416, GSE42519, GSE55849, GSE72642, GSE6054, GSE13899, GSE16836, GSE60601, GSE66936, GSE72642, and GSE76803 datasets. Downloaded data were obtained from the GeneChip Human

Genome U133 Plus 2.0 Array (GPL570) platform and have been normalized with the DNA-Chip Analyzer (dChip) software28. The normalization was performed using an array with median overall

intensity chosen as the baseline array against which other arrays are normalized at probe intensity level. In this way the brightness of the arrays was adjusted to comparable level. We

utilized the same software to compute model-based expression values for each array. LIMMA package was utilized for statistical analysis of differential expression29. Different p values

obtained for each probe of the same gene were combined using the Fisher test. _p_ < 0.001 calculated on AML and CD34 with respect to mature myeloid cells was considered as statistically

significant. MeRIP-Seq (GSM2010455, GSM2010456), m6A CLIP (GSM1828594, GSM1828596, GSM2300426) and METTL3 PAR-CLIP (GSM1135006, GSM1135007) datasets were obtained from GEO. Data from real

time PCR analysis were subjected to the two-tailed Student’s _t_ test. All values in figures are presented as the mean ± standard error of mean (SEM) of _n_ independent experiments. _p_

Values of <0.05 were considered to be statistically significant and indicated by 1 asterisk in figures. OLIGONUCLEOTIDES Cloning: METTL3_HindIII_FW: CKnockdown of METTL3 results in an

increase of WTAP protein levelsGGACACGTGGAGC METTL3_NotI_REV: ATTTGCGGCCGCCTATAAATTCTTAGGTTTAGAGAT WTAP_BamHI_FW: CGCGGATCCATGACCAACGAAGAACCTCT WTAP_NotI_REV:

ATTTGCGGCCGCTTACAAAACTGAACCCTGTACA APPA_mettl3_FW: CCCGCCGATATTCACATGGAACTGCCCTAT APPA_mettl3_REV: TGGGGCAGCCATCACAACTGCAAACT WTAP_flag_FW: GACGACGATAAGACCAACGAAGAACCTCTTCCCAA WTAP_flag_FW:

GACGACGATAAGACCAACGAAGAACCTCTTCCCAA WTAP_flag_REV: ATCCTTGTAATCCATGGATCCGAGCTCGGTACCAA METTL3_flag_FW: GACGACGATAAGTCGGACACGTGGAGCTCTATCC METTL3_flag_rev:

ATCCTTGTAATCCATAAGCTTAAGTTTAAACGCTAGCCA WTAP_m6Adel_iPCR_REV: TTCATCCTGACTGCTTTTAAGCTC WTAP_pcDNA_FW: TAAGCGGCCGCTCGAGT qRT-PCR: ACTB_hs_FW: CGTACCACTGGCATC ACTB_hs_REV: GTAGTCAGTCAGGTCCCGGC

METTL3 SYBR FW: AAGCAGCTGGACTCTCTGCG METTL3 SYBR REV: GCACTGGGCTGTCACTACGG WTAP SYBR FW: TGCGACTAGCAACCAAGGAA WTAP SYBR REV: ATCTCAGTTGGGCAACGCTC WTAP SYBR REV2: CTGTGTACTTGCCCTCCAAAG

WTAP_pre-mRNA FW: TCATTTTGTGATGGATGGCTCT WTAP_pre-mRNA REV: TCAAGTTGTGCAATACGTCCC WTAP_5′UTR_FW: TTCTGCCTGGAGAGGATTCA WTAP_long_FW: TCCAGTCATGACCCTCAAGAG WTAP_long_REV: AGTCCAAGCCATTCTGAACG

HPRT SYBR FW: GCCATCACATTGTAGCCCTCTG HPRT SYBR REV: TTTATGTCCCCTGTTGACTGGTC FLAG_FW: GATTACAAGGATGACGACGATAAG YTHDF2_SYBR_FW: GAACCTTACTTGAGTCCACAG YTHDF2_SYBR_REV: GTAGGGCATGGCTGTGTCAC

TAZ_SYBR_FW: TCACTGTGCTGATCGGGAAG TAZ_SYBR_REV: TCTCCACAGCCGACTTGTTC REFERENCES * Zhao, B. S., Roundtree, I. A. & He, C. Post-transcriptional gene regulation by mRNA modifications. _Nat.

Rev. Mol. Cell Biol._ 1, 31–42 (2017). Article CAS Google Scholar * Knuckles, P. et al. Zc3h13/Flacc is required for adenosine methylation by bridging the mRNA-binding factor

Rbm15/Spenito to the m(6)A machiner component Wtap/Fl(2)d. _Genes Dev._ 32, 415–429 (2018). Article PubMed PubMed Central CAS Google Scholar * Wang, P., Doxtader, K. A. & Nam, Y.

Structural basis for cooperative function of Mettl3 and Mettl14 methyltransferases. _Mol. Cell_ 63, 306–317 (2016). Article PubMed PubMed Central CAS Google Scholar * Wang, X. et al.

Structural basis of N(6)-adenosine methylation by the METTL3–METTL14 complex. _Nature_ 534, 575–578 (2016). Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar * Śledź, P. & Jinek, M. Structural

insights into the molecular mechanism of the m(6)A writer complex. _eLife_ 5, e18434 (2016). Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Pendleton, K. E. et al. The U6 snRNA m(6)A

methyltransferase METTL16 regulates SAM synthetase intron retention. _Cell_ 169, 824–835 (2017). Article PubMed PubMed Central CAS Google Scholar * Warda, A. S. et al. Human METTL16 is

a N(6)-methyladenosine (m(6)A) methyltransferase that targets pre-mRNAs and various non-coding RNAs. _EMBO Rep._ 18, 2004–2014 (2017). Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar * Patil, D. P.,

Pickering, B. F. & Jaffrey, S. R. Reading m(6)A in the transcriptome: m(6)A-binding proteins. _Trends Cell Biol._ 28, 113–127 (2018). Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar * Lin, S.,

Choe, J., Du, P., Triboulet, R. & Gregory, R. I. The m(6)A methyltransferase METTL3 promotes translation in human cancer cells. _Mol. Cell_ 62, 335–345 (2016). Article PubMed PubMed

Central CAS Google Scholar * Coots, R. A. et al. m(6)A facilitates eIF4F-independent mRNA translation. _Mol. Cell_ 68, 504–514 (2017). Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar * Bansal, H.

et al. WTAP is a novel oncogenic protein in acute myeloid leukemia. _Leukemia_ 28, 1171–1174 (2014). Article PubMed PubMed Central CAS Google Scholar * Little, N. A., Hastie, N. D.

& Davies, R. C. Identification of WTAP, a novel Wilms’ tumour 1-associating protein. _Hum. Mol. Genet._ 9, 2231–2239 (2000). Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar * Figueroa, A. et al.

Novel roles of hakai in cell proliferation and oncogenesis. _Mol. Biol. Cell_ 20, 3533–3542 (2009). Article PubMed PubMed Central CAS Google Scholar * Horiuchi, K. et al. Identification

of Wilms’ tumor 1-associating protein complex and its role in alternative splicing and the cell cycle. _J. Biol. Chem._ 288, 33292–33302 (2013). Article PubMed PubMed Central CAS Google

Scholar * Ping, X. L. et al. Mammalian WTAP is a regulatory subunit of the RNA N6-methyladenosine methyltransferase. _Cell Res._ 24, 177–189 (2014). Article PubMed PubMed Central CAS

Google Scholar * Jaffrey, S. R. & Kharas, M. G. Emerging links between m(6)A and misregulated mRNA methylation in cancer. _Genome Med._ 9, 2 (2017). Article PubMed PubMed Central CAS

Google Scholar * Vu, L. P. et al. The N(6)-methyladenosine (m(6)A)-forming enzyme METTL3 controls myeloid differentiation of normal hematopoietic and leukemia cells. _Nat. Med._ 23,

1369–1376 (2017). PubMed PubMed Central CAS Google Scholar * Barbieri, I. et al. Promoter-bound METTL3 maintains myeloid leukaemia by m(6)A-dependent translation control. _Nature_ 55,

126–131 (2017). Google Scholar * Su, R. et al. R-2HG exhibits anti-tumor activity by targeting FTO/m(6)A/MYC/CEBPA signaling. _Cell_ 172, 1–16 (2018). Article CAS Google Scholar * Weng,

H. et al. METTL14 inhibits hematopoietic stem/progenitor differentiation and promotes leukemogenesis via mRNA m(6)A modification. _Cell Stem Cell_ 2, 1–15 (2018). Google Scholar * Liu, J.

et al. A METTL3–METTL14 complex mediates mammalian nuclear RNA N6-adenosine methylation. _Nat. Chem. Biol._ 10, 93–95 (2014). Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar * Ke, S. et al. A majority

of m6A residues are in the last exons, allowing the potential for 3′-UTR regulation. _Genes Dev._ 29, 2037–2053 (2015). Article PubMed PubMed Central CAS Google Scholar * Ke, S. et al.

m(6)A mRNA modifications are deposited in nascent pre-mRNA and are not required for splicing but do specify cytoplasmic turnover. _Genes Dev._ 31, 990–1006 (2017). Article PubMed PubMed

Central CAS Google Scholar * Tam, S. W., Theodoras, A. M. & Pagano, M. Kip1 degradation via the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway. _Leukemia_ 11, 363–366 (1997). PubMed Google Scholar *

Salvatori, B. et al. The microRNA-26a target E2F7 sustains cell proliferation and inhibits monocytic differentiation of acute myeloid leukemia cells. _Cell Death Dis._ 3, e413 (2012).

Article PubMed PubMed Central CAS Google Scholar * Wiederschain, D. et al. Single-vector inducible lentiviral RNAi system for oncology target validation. _Cell Cycle_ 8, 498–504 (2009).

Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar * Dominissini, D., Moshitch-Moshkovitz, S., Salmon-Divon, M., Amariglio, N. & Rechavi, G. Transcriptome-wide mapping of N(6)-methyladenosine by

m(6)A-seq based on immunocapturing and massively parallel sequencing. _Nat. Protoc._ 8, 176–189 (2013). Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar * Cheng, L. Automating dChip: toward

reproducible sharing of microarray data analysis. _BMC Bioinformatics_ 9, 231 (2008). Article CAS Google Scholar * Smyth, G. K. Linear models and empirical Bayes methods for assessing

differential expression in microarray experiments. _Stat. Appl. Genet. Mol. Biol._ 3, 3 (2004). Article Google Scholar Download references ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The authors would like to thank

Dr. A. Rosa and Dr. A. Brivanlou for the ePiggyBac inducible transposon system, M. Arceci for technical assistance, and A. Colantoni for bioinformatics support. The results shown here are in

part based upon data generated by the TCGA Research Network: http://cancergenome.nih.gov/. This work was supported by A.I.R.C. (IG 17352) and “Progetti Ateneo” Sapienza University of Rome.

AUTHOR INFORMATION AUTHORS AND AFFILIATIONS * Department of Biology and Biotechnology “C. Darwin”, Sapienza University of Rome, 00185, Rome, Italy Melissa Sorci, Zaira Ianniello, Sonia

Cruciani, Simone Larivera, Lavinia Ceci Ginistrelli & Alessandro Fatica * Department of Anatomical, Histological, Forensic and Orthopaedic Sciences, Sapienza University of Rome, 00185,

Rome, Italy Ernestina Capuano & Francesco Fazi * Institute of Biology, Molecular Medicine and Nanobiotechnology, CNR, Sapienza University of Rome, Rome, Italy Marcella Marchioni *

Istituto Pasteur Italia-Fondazione Cenci Bolognetti, 00185, Rome, Italy Francesco Fazi Authors * Melissa Sorci View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google

Scholar * Zaira Ianniello View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Sonia Cruciani View author publications You can also search for this author

inPubMed Google Scholar * Simone Larivera View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Lavinia Ceci Ginistrelli View author publications You can

also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Ernestina Capuano View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Marcella Marchioni View author

publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Francesco Fazi View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Alessandro

Fatica View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar CORRESPONDING AUTHOR Correspondence to Alessandro Fatica. ETHICS DECLARATIONS CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest. ADDITIONAL INFORMATION PUBLISHER'S NOTE: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published

maps and institutional affiliations. Edited by: M. Herold ELECTRONIC SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL SUPPLEMENTAL FIGURE 1 SUPPLEMENTAL FIGURE 2 SUPPLEMENTAL FIGURE 3 SUPPLEMENTAL FIGURE 4

SUPPLEMENTAL FIGURE 5 RIGHTS AND PERMISSIONS OPEN ACCESS This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation,

distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and

indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to

the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will

need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. Reprints and permissions ABOUT THIS ARTICLE

CITE THIS ARTICLE Sorci, M., Ianniello, Z., Cruciani, S. _et al._ METTL3 regulates WTAP protein homeostasis. _Cell Death Dis_ 9, 796 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41419-018-0843-z

Download citation * Received: 16 March 2018 * Revised: 28 June 2018 * Accepted: 02 July 2018 * Published: 23 July 2018 * DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41419-018-0843-z SHARE THIS ARTICLE

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content: Get shareable link Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article. Copy to clipboard Provided

by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative