Old dogs, new trick: classic cancer therapies activate cgas

- Select a language for the TTS:

- UK English Female

- UK English Male

- US English Female

- US English Male

- Australian Female

- Australian Male

- Language selected: (auto detect) - EN

Play all audios:

ABSTRACT The discovery of cancer immune surveillance and immunotherapy has opened up a new era of cancer treatment. Immunotherapies modulate a patient’s immune system to specifically

eliminate cancer cells; thus, it is considered a very different approach from classic cancer therapies that usually induce DNA damage to cause cell death in a cell-intrinsic manner. However,

recent studies have revealed that classic cancer therapies such as radiotherapy and chemotherapy also elicit antitumor immunity, which plays an essential role in their therapeutic efficacy.

The cytosolic DNA sensor cyclic GMP-AMP synthase (cGAS) and the downstream effector Stimulator of Interferon Genes (STING) have been determined to be critical for this interplay. Here, we

review the antitumor roles of the cGAS-STING pathway during tumorigenesis, cancer immune surveillance, and cancer therapies. We also highlight classic cancer therapies that elicit antitumor

immune responses through cGAS activation. SIMILAR CONTENT BEING VIEWED BY OTHERS THE CGAS–STING PATHWAY AND CANCER Article 12 December 2022 CGAS AND CANCER THERAPY: A DOUBLE-EDGED SWORD

Article 18 January 2022 THE BALANCE OF STING SIGNALING ORCHESTRATES IMMUNITY IN CANCER Article 25 June 2024 INTRODUCTION Humanity’s battle against cancer has been ongoing for thousands of

years with surgical removal of tumors being the first treatment recorded in Ancient Egypt.1 While surgery is still a first line treatment for cancer in modern times, it does not prevent

systemic tumors and is limited by tumor accessibility and location. Beginning in the 20th century, classic cancer therapies that cause robust DNA damage and cell death became available.

Classic therapies such as radiotherapy and chemotherapy became the major cancer treatments performed in the clinic; nevertheless, not all cancers respond to classic therapies, driving

research towards new therapeutic strategies. More recently, rapid progress has been made in the field of cancer immunology. The theory of cancer immune surveillance was formed in the late

20th century, suggesting that the immune system can identify and kill cancer cells.2 This idea was later confirmed upon detection of tumor antigen-specific CD8+ T cells in patients and led

to the development of cancer immunotherapies such as immune checkpoint blockade.3,4,5 How can the immune system be activated by cancer cells in the absence of an infection? Cyclic GMP-AMP

synthase (cGAS) is a cytosolic DNA sensor and was originally found to sense pathogen DNA during infection. Subsequent studies revealed that cGAS also detects tumor-derived DNA, initiating

antitumor immunity. Moreover, cGAS provides additional antitumor roles by detecting DNA damage in premalignant cells or in cancer cells treated with classic cancer therapies. In this review,

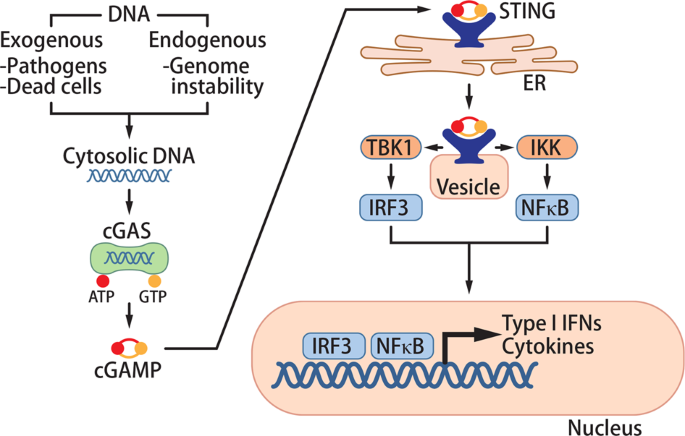

we provide an overview of the antitumor mechanisms of cGAS-mediated immune responses. THE CGAS-STING PATHWAY The innate immune system provides the first line of defense against pathogen

infection. Pathogen recognition receptors (PRRs) initiate innate immune responses by binding to corresponding pathogen- or damage-associated molecular patterns. cGAS was first discovered as

a cytosolic PRR that detects pathogen DNA (Fig. 1). While self-DNA is compartmentalized in the nucleus or mitochondria, pathogen DNA is released into the cytosol during infection of cells.

cGAS binds to this DNA in the cytosol and converts ATP and GTP into 2′3′-cyclic GMP-AMP (cGAMP).6,7,8 cGAMP functions as a second messenger that binds to the adapter protein stimulator of

interferon genes (STING) on the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) membrane.7,9,10,11,12 Upon cGAMP binding, STING traffics from the ER to the Golgi apparatus and activates TANK-binding kinase 1

(TBK1) and IκB kinase (IKK).13 These kinases activate the transcription factors interferon regulatory factor 3 (IRF3) and NF-κB, respectively, to induce the production of type I interferons

(IFNs) and other cytokines.14,15 These cytokines orchestrate immune responses to eliminate pathogens such as DNA viruses, retroviruses, and intracellular bacteria.16,17,18,19 In addition,

STING activation induces autophagy to clear intracellular pathogens in a TBK1-independent manner.20,21 cGAS and STING are tightly regulated through transcriptional regulation,

post-translational modifications, and protein degradation as noted in a previous review.16 As cGAS binds the backbone of double-stranded DNA without sequence specificity,22,23 cGAS can also

be activated by cytosolic self-DNA that leaks out from membranous organelles. Intracellular DNases prevent cGAS from detecting self-DNA by reducing cytosolic DNA levels; three prime repair

exonuclease 1 (TREX1) and deoxyribonuclease II (DNase II) degrade DNA in the cytosol and lysosomes, respectively. In mice lacking either of these DNases, cGAS is activated by self-DNA and

the mice develop severe autoimmune diseases.24,25 Similarly, patients with gain-of-function mutations in STING or loss-of-function mutations in TREX1 or DNase II showed an overactive

cGAS-STING pathway and severe autoimmune phenotypes.26,27 Additional studies found that cGAS is involved in diseases characterized by “sterile inflammation” such as heart failure, fibrosis,

geographic atrophy, and cancer.28,29,30 THE ROLE OF CGAS IN ANTITUMOR IMMUNITY CANCER IMMUNE SURVEILLANCE Cancer cells acquire abnormal features such as uncontrolled proliferation by

accumulating mutations. Although cancer cells originated from endogenous tissues, the immune system recognizes cancer cells as “foreign cells” and target them for destruction. This concept

of “cancer immune surveillance” was first recognized in cases of immunodeficiency in which immunocompromised patients or mice presented with higher risks of developing tumors.31,32

Subsequent studies showed that tumor antigen-specific CD8+ T cells infiltrate tumor sites where they selectively kill cancer cells.3,4,5 Activation of CD8+ T cells requires two signals from

antigen-presenting cells: the tumor-specific antigen and co-stimulatory molecules. Tumor-specific antigens derive from cancer cells that express abnormal proteins. While co-stimulatory

molecules were known to arise from activation of PRRs and the downstream immune signaling pathway, the cancer-specific pathway was not yet determined. After type I IFNs were shown to be

associated with CD8+ T cell activation in cancer patients,33 additional studies determined that they stimulated CD8α+ dendritic cells to activate CD8+ T cells.34,35 Several PRRs such as the

toll-like receptors (TLRs), RIG-I-like receptors (RLRs), and cGAS can induce type I IFNs upon activation. However, only STING-deficient mice showed defective tumor-specific CD8+ T cells and

accelerated tumor growth, suggesting that the cGAS-STING pathway is a major pathway that spontaneously detects cancer.36 DNA or cGAMP from tumors activates the cGAS-STING pathway to initiate

antitumor immunity. Tumor DNA was detected in the cytosol of host cells and subsequently induced type I IFNs in dendritic cells and endothelial cells.36,37 The mechanism by which tumor DNA

is transferred to the cytosol of non-tumor cells remains to be resolved. Due to genome instability, some tumor cells spontaneously produce cGAMP, which is transferred to non-tumor cells;

tumor cGAS and host STING were required for antitumor immune responses, supporting the cGAMP transfer model.38,39 So far, gap junctions, SLC19A1, P2X7R, and LRRC8 were reported to transmit

cGAMP from cell to cell or from the extracellular region to cells.40,41,42,43,44,45 Altogether, spontaneous cancer immune surveillance is induced by tumor-derived DNA or cGAMP transferred

into host cells (Fig. 2b). Although the immune system has a critical antitumor effect, persistent inflammation can promote tumor growth and metastasis.46 In an inflammation-driven epithelial

cancer model, the carcinogen DMBA activated the cGAS pathway to induce inflammation that promoted tumorigenesis; STING-deficient mice were resistant to DMBA-induced tumorigenesis.47 In a

brain tumor model, cGAMP generated in cancer cells was transferred to astrocytes through gap junctions to induce inflammation and metastasis.48 Thus, the cGAS-STING pathway also has protumor

functions by promoting inflammation-driven tumorigenesis and metastasis. The extent of the protumor effect may depend on levels of genome instability and cGAS activation in tumor cells.

Despite the protumor aspect of inflammation, acute activation of immunity was shown to have a strong antitumor effect. As a widely recognized endogenous sensor of tumors, cGAS and its

downstream signaling pathway are strong therapeutic targets for cancer immunotherapy. CANCER IMMUNOTHERAPY Cancer immunotherapy focuses on enhancing antitumor immune responses to target

cancer cells specifically. In the late 19th century, inactivated bacteria was shown to reduce sarcomas in patients.49 Further groundbreaking findings in cancer immunology led to the

development of several immunotherapies, including immune checkpoint blockade.50 Programmed cell death protein 1 (PD-1) on the T cell membrane interacts with its ligand programmed

death-ligand 1 (PD-L1) to prevent over-activation of T cells.51 Cancer cells induce PD-L1 expression to suppress tumor-specific T cells, but this immune evasion can be overcome by blocking

the interaction between PD-1 and PD-L1. Antibodies targeting PD-1 or PD-L1 to prevent cancer immune tolerance are FDA-approved for treating several tumors.52 Despite successful treatment of

many cancer patients with immune checkpoint inhibitors, the overall response rate of the therapy is low.53 Fostering a CD8+ T cell-rich tumor environment may enhance the responsiveness of

immune checkpoint inhibitors. As an endogenous pathway for tumor-specific T cell activation, the cGAS-STING pathway is a potent therapeutic target. Importantly, cGAS was essential for the

therapeutic effect of PD-L1 antibody as no therapeutic effect was observed in antibody-treated cGAS-deficient mice implanted with tumors: this is due to the need for activation of

tumor-specific T cells to precede immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy.54 Many therapeutic strategies targeting the cGAS-STING pathway have been developed and tested in preclinical models.55

2′3′-cGAMP, the endogenous ligand of STING, reduced implanted tumor growth by activating and recruiting CD8+ T cells to the tumor microenvironment.37,54 Combining cGAMP and immune checkpoint

inhibitors induced a synergistic effect in controlling tumor growth, demonstrating that activation of STING can potentiate the effect of immune checkpoint inhibitors.37,54,56 Although cGAMP

has been determined to have a potent antitumor effect, it is degraded by ecto-nucleotide pyrophosphatase/phosphodiesterase (ENPP1) in the serum.57 This finding led to the development of

STING agonists that are resistant to ENPP1 degradation. In contrast to the results obtained from mouse tumor models, these STING agonists alone did not show prominent antitumor effects in

early clinical trials; nevertheless, outcomes were more promising when combined with an immune checkpoint inhibitor (NCT03010176, NCT03172936). As patient tumors have a diverse genetic

background and engage multiple immune evasion mechanisms compared to implanted mouse tumors, combining multiple cancer treatments together with STING agonists may be a better approach for

patient treatment. In this regard, other STING agonists also enhanced the antitumor effect when combined with tumor vaccines, chemotherapy, or radiotherapy: such applications of STING

agonists are expected to continue to expand.55 Moreover, the newly identified role of cGAS in the DNA damage response (DDR) widens the scope of immunotherapies (see below). THE ROLE OF CGAS

IN THE DNA DAMAGE RESPONSE DNA, the blueprint of life, is protected by a series of DDR pathways to maintain genomic integrity. DDR pathways halt the cell cycle and repair DNA; the cell cycle

resumes after repairs. If the damage is not resolved, cells undergo an irreversible cell cycle arrest called cellular senescence.58 If DNA is left severely damaged, the DDR directs cells to

undergo apoptosis. Although the type of DNA damage varies, micronuclei are a traditional biomarker of DNA damage and chromosome instability.59 A micronucleus is a small nucleus-like body

that is composed of fragments of chromosomes surrounded by a fragile nuclear envelope. They can be generated during mitosis from chromatid fragments formed by DNA double-strand breaks (DSBs)

or from lagging chromosomes formed by mis-segregation.60 Although micronuclei have been extensively studied since their discovery in the 19th century, their physiological function has

remained obscure and micronuclei were simply treated as a readout of genome instability. However, the discovery of cGAS activation in the micronuclei provides a link between DNA damage and

innate immune responses. Multiple studies have now reported that micronuclei activate cGAS.61,62,63,64,65 The nuclear envelope of micronuclei easily ruptures due to lack of a stable nuclear

lamina.66 Micronuclear DNA co-localized with cGAS after micronuclear membrane collapse: this colocalization was enhanced when Lamin B1 was downregulated, indicating that the rupture of the

micronuclear membrane precedes DNA detection by cGAS.63,65 As premalignant cells accumulate micronuclei due to their unstable genome, subsequent activation of cGAS can promote cellular

senescence. Chromatin in micronuclei is presumably the ligand of cGAS. Indeed, cGAS shows affinity for chromatin and co-localizes with nuclear chromatin during mitosis after nuclear envelope

breakdown.64,67,68 However, nuclear chromatin, unlike micronuclear chromatin, does not activate cGAS. Micronuclear DNA accumulate DSBs that may reveal cGAS ligands; a structural study of

cGAS–DNA complexes suggested preferential binding of cGAS to the terminal regions of dsDNA.22 Fragmentation of chromatin may also remove nucleosome packing, which inhibits cGAS activation.68

Endogenous defects in the DDR can also activate cGAS and induce autoinflammatory diseases. Aicardi-Goutières syndrome (AGS) is a severe neurodevelopmental disorder characterized by high

levels of type I IFNs. AGS patients harbor mutations in genes encoding enzymes involved in nucleic acid metabolism, including TREX1, SAMHD1, and RNaseH2.69 SAMHD1 is a dNTPase that restricts

reverse transcription of retroviruses and facilitates exonuclease function during DSB repair; SAMHD1 deficiency leads to DNA damage that activates the cGAS pathway.70 RNaseH2 excises

misincorporated ribonucleotides from DNA; its deficiency induces micronuclei formation and cGAS activation to cause AGS.63 Removal of STING or cGAS rescued RNasH2-mutant mice from

autoinflammatory phenotypes.71 The genetic disease ataxia-telangiectasia (A-T) is caused by dysfunction of the ataxia-telangiectasia mutated (ATM) protein, a central mediator of DSB

repair.72 As a result, the adaptive immune system, which requires DNA recombination for T and B cell development, is defective in A-T patients.73 In contrast, innate immune responses are

over-activated and produce excessive amounts of type I IFNs. The cGAS-STING pathway was found to be responsible for this severe inflammation as genetic ablation of STING in the ATM-deficient

mouse model greatly reduced the IFN signature.74 While micronuclear cGAS detects DNA damage and induces immune responses, nuclear cGAS was recently shown to suppress DNA repair in a

STING-independent manner. Homologous recombination, a critical step of DSB repair, was inhibited when nuclear cGAS compacted DNA or interfered with the function of a DNA repair enzyme.67,75

As genome instability promotes tumorigenesis, nuclear cGAS may have a protumor function.67 As cGAS in tumor cells has both anti- and protumor roles based on its localization, it is important

to understand how cGAS localization is regulated among tumor cells. THE CGAS-STING PATHWAY AND CELLULAR SENESCENCE Cellular senescence is a state of irreversible cell cycle arrest that

occurs under severe cellular stress. The senescent state is naturally induced after cells undergo multiple rounds of proliferations due to shortening of telomeres or accumulation of DNA

damage.76 It can also result from exogenous stress such as oxygen radicals and radiation. These senescence signals activate the p53 or p16-retinoblastoma protein pathways to halt the cell

cycle.76 The senescence state was predominant in premalignant tumors and was essential for suppression of tumorigenesis.77,78,79 In addition to halting their own proliferation, senescent

cells secrete inflammatory cytokines, growth factors, and proteases, a phenotype termed the senescence-associated secretory phenotype (SASP). The SASP reinforces senescence growth arrest in

an autocrine manner and spreads growth inhibition in a paracrine manner.80 In addition, chemokines from the SASP can activate and recruit immune cells to eliminate aberrant cells harboring

DNA damage.81 Multiple studies reported that DNA damage sensing by the cGAS-STING pathway is critical for the SASP (Fig. 2a).61,62,64,65 cGAS- or STING-deficient cells showed reduced

senescence after serial passage, irradiation, treatment of DNA-damaging drugs, or oncogene expression; these senescence activators also induced micronuclei, which activate cGAS.61,62,64,65

In the oncogene model, RasV12-expressing premalignant hepatocytes induced the SASP and were then eliminated by immune cells.82 In the absence of cGAS or STING, the SASP and immune cell

infiltration were defective; moreover, impaired clearance of RasV12-expressing cells eventually led to the development of tumors.61,65 In the colitis-associated cancer model induced by

chronic DNA damage and inflammation, mice lacking STING were more susceptible to tumors.83,84 These studies indicate that the cGAS-STING pathway-induced SASP may prevent tumorigenesis by

reinforcing senescence or augmenting immune cell-mediated clearance of aberrant cells. Consistent with the role of the cGAS-STING pathway in senescence and tumorigenesis, several cancer

cells and immortalized cells downregulate cGAS or STING expression.6,85 Low levels of cGAS or STING in cancer cells are associated with poor prognosis of lung adenocarcinoma and

hepatocellular carcinoma, suggesting cell-autonomous tumor-suppressing functions of the cGAS-STING pathway.64,86 In addition to the SASP, STING-induced autophagy may provide an additional

barrier against tumorigenesis in senescence-bypassed cells by inducing cell death; cGAS- or STING-deficient cells escaped autophagic cell death induced by telomeric DNA damage and continued

to proliferate.87 Further studies are needed to understand the role of STING-induced autophagy in tumors as autophagy is known to prevent tumorigenesis by removing DNA damage inducers but is

also known to support tumor cells by providing cellular building blocks and energy.88 Despite the importance of cGAS in preventing tumorigenesis, loss of cGAS expression alone does not

induce tumors.64 This is consistent with the requirement for mutations in multiple oncogenes and tumor suppressor genes in order for a normal cell to transform into a malignant cancer cell.

cGAS may exert tumor suppressive effect by providing additional barriers for premalignant cells that are exposed to chronic DNA damage or have mutations in oncogenes or tumor suppressor

genes. Even with these barriers against tumorigenesis, some premalignant cells overcome senescence to form tumor cells. When cGAS is continuously activated in these tumor cells by cytosolic

DNA, the canonical and non-canonical NF-κB pathways are induced, leading to chronic inflammation that promotes tumor growth and metastasis.61,89 These studies suggest that the relation

between cGAS and tumors may depend on tumor type and the stage of tumorigenesis. THE CGAS-STING PATHWAY AND RADIOTHERAPY OF CANCER Radiotherapy, which uses ionizing radiation to induce DSBs

and cell death, is given to ~50% of cancer patients and is a major cancer treatment along with surgery and chemotherapy.90 Interestingly, in certain cases, radiotherapy shrank tumors that

are not directly irradiated (abscopal effect), indicating that DNA damage-induced cell death is not the sole mechanism of radiotherapy.91 Later studies revealed that the immune system,

particularly CD8+ T cells, plays a role in the therapeutic effect of radiotherapy.92 In addition, radiotherapy induced type I IFNs at the tumor site, and type I IFN receptors on immune cells

were critical for the effect of radiotherapy.93 Subsequent studies show that the cGAS-STING pathway promotes antitumor immunity after radiotherapy in two ways: detection of DNA damage in

cancer cells and increased detection of tumor-derived DNA in immune cells (Fig. 2b, c). Multiple studies showed that radiation-induced DNA damage causes the formation of micronuclei that

then activate the cGAS-STING pathway (Fig. 3).61,62,63,64,65 To study whether cGAS activation in irradiated cancer cells contributes to antitumor immunity, the abscopal effect of radiation

was investigated. A mouse model was implanted with tumors on one side and injected with irradiated cancer cells at the other side.62 Injection of irradiated cancer cells intensified the

antitumor immune responses and reduced the contralateral tumor size when combined with an immune checkpoint inhibitor; this effect required STING expression in irradiated cancer cells.62

Moreover, direct radiation of implanted STING-deficient tumors did not provide an abscopal effect. This study suggests that cancer cell-intrinsic activation of the cGAS-STING pathway by

radiotherapy promotes antitumor immunity. Another study showed that radiation-induced cell death activates the cGAS-STING pathway in immune cells and potentiates antitumor immunity.94 In

this study, implanted tumors were directly irradiated in mouse strains deficient in one of several immune signaling pathways; only tumors implanted in STING-deficient mice were resistant to

radiotherapy. Dendritic cells were able to detect irradiated cancer cells in a cGAS-dependent manner and induced high levels of type I IFNs in the tumor microenvironment.94 This study

suggests that the cGAS-STING pathway in dendritic cells detects more tumor-derived DNA after radiotherapy. Increased detection of tumor-derived DNA is probably due to increased cell death

after irradiation, as the phagocytic ability of dendritic cells was required for this detection.94 The cGAS-STING pathway provides a link between radiotherapy and activation of antitumor

immunity. However, high doses of radiation may adversely suppress the immune system; in fact, the most common side effect of radiotherapy is immune suppression. As radiotherapy damages DNA,

fast proliferating cells such as cancer cells but also immune cells are affected. Alternatively, radiation-induced activation of cGAS can turn on a negative feedback loop. When radiation

doses were above 12–18 Gy, TREX1, an interferon-stimulated gene (ISG), was induced to degrade cytosolic DNA and downregulate the cGAS pathway.95 cGAS activation by radiation also upregulates

PD-L1, which suppresses antitumor T cells.96 Overcoming these hurdles to activate immune responses will be a future direction of radiotherapy. Preclinical studies showed that repeated

irradiation at low doses does not induce TREX1 and mediates tumor rejection.95 PD-L1 antibody treatment reversed T cell suppression and showed a synergistic therapeutic effect when combined

with radiotherapy.94 Moreover, combining radiotherapy and cGAMP elicited stronger tumor-specific CD8+ T cell responses and showed complete tumor rejection in 70% of mice with implanted

tumors.94 Revealing an immunomodulatory role of radiotherapy opens up more possibilities of combining it with other immunotherapies. Clinical trials on combining radiotherapy and immune

checkpoint blockade are ongoing and will provide new insights in advancing therapeutic approaches.97 THE CGAS-STING PATHWAY AND CHEMOTHERAPY Chemotherapy, which interferes with cell

proliferation, is a major treatment given to cancer patients. It was previously assumed that chemotherapy drugs act directly on cancer cells to induce cell death; however, some studies

observed the activation of antitumor immunity after chemotherapy.98,99 A later study then concluded that increased cell death by chemotherapy releases danger-associated molecules that can

activate the immune system.100 More recent studies are now suggesting that chemotherapy drugs may also have direct immunostimulatory effects through activating cGAS in cancer cells (Fig.

2c). A growing number of studies are reporting cGAS activation by micronuclei during chemotherapy treatment. Moreover, cancer cell-intrinsic activation of cGAS promoted antitumor immunity,

which was critical for the full therapeutic effect of certain chemotherapy drugs.101,102 These new findings shift our paradigm of chemotherapy from only being cytotoxic drugs to also having

immunostimulatory functions. This realization now raises the need to reinterpret the role of various chemotherapy drugs and develop new applications for chemotherapy and immunotherapy. In

this section, we summarize the chemotherapy drugs that are reported to activate the cGAS-STING pathway and their suggested mechanisms of action (Table 1; Fig. 3). PARP INHIBITOR Cancer cells

often have defects in the DDR. For example, breast cancer type 1 susceptibility protein (BRCA1) repairs DSBs by homologous recombination and is often mutated in breast and ovarian

cancers.103 Loss of BRCA function allows premalignant cells to accumulate mutations and potentially transform into cancer cells. In order to maintain minimal genome integrity, these

BRCA-deficient cancer cells rely more on the remaining intact DDR pathways, such as single-strand break (SSB) repair. Poly (ADP ribose) polymerase 1 (PARP1) initiates the repair of SSBs that

can develop into detrimental DSBs. BRCA-deficient cancer cells cannot repair DSBs accumulated by PARP inhibition and thus undergo apoptosis.104 Several PARP inhibitors such as olaparib,

rucaparib, niraparib, and talazoparib are FDA-approved to treat multiple cancers including BRCA-deficient breast and ovarian tumors. Recent studies showed that these PARP inhibitors induced

micronuclei formation in cancer cell lines and induced ISGs in a cGAS- and STING-dependent manner.101,102,105,106,107,108 In mouse implanted tumor models, PARP inhibitors increased

infiltration of CD8+ T cells to the tumor site. Moreover, the antitumor effect of PARP inhibitors markedly decreased after CD8+ T cell depletion, suggesting that an important therapeutic

mechanism of PARP inhibitors is to stimulate the immune system.101,102 This immunostimulatory effect of PARP inhibitors was not observed when STING-deficient cancer cells were implanted,

indicating that PARP inhibitors activate the cGAS-STING pathway in a cancer cell-intrinsic manner to promote antitumor immunity.101,102 Activation of cGAS was stronger in BRCA-deficient

cancer cell lines, which accumulate more DNA damage upon PARP inhibition.101,108 Nevertheless, several studies observed some activation of the cGAS-STING pathway in BRCA-proficient cancer

cell lines, possibly due to minor DNA damage.102,106 Clinically, PARP inhibitors have shown benefits in both BRCA-proficient and BRCA-deficient tumors.109,110 Antitumor immunity induced by

cGAS activation might be one explanation for the clinical benefit found in BRCA-proficient tumors; nevertheless, this hypothesis requires additional testing. PARP inhibitors also activated

cGAS in cancer cells defective in DNA excision repair protein (ERCC1), which is involved in both nucleotide excision repair and DSB repair.105 Altogether, these studies show that PARP

inhibitors activate cGAS in cancer cells and promote antitumor immunity. The newly discovered immunostimulatory function of PARP inhibitors offers new insights into improving cancer patient

treatments. Activation of cGAS leads to recruitment of CD8+ T cells into tumors but also upregulation of PD-L1 expression on PARP inhibitor-treated cancer cells, thereby sensitizing tumors

to PD-L1 immune checkpoint therapy.102,105,106,111 Treatment with a PARP inhibitor and a PD-1/PD-L1 antibody showed a synergistic antitumor effect in mouse tumor models102,105,106,111;

combining niraparib (PARP inhibitor) with pembrolizumab (anti-PD-1) had a promising antitumor activity for patients with breast or ovarian cancer.112,113 Combining drugs that target

different DDR proteins such as PARP and A-T and Rad3-related protein (ATR) further increased micronuclei formation, indicating stronger cGAS activation.114 Synergistic effects may not be

observed in all cancer treatments since many cancer cells, including several ovarian cancer cells, lack cGAS or STING expression.85,115 Nevertheless, PARP inhibition is also able to elicit

antitumor immunity by effectively killing cancer cells and releasing more tumor-derived DNA to stimulate the cGAS-STING pathway in immune cells.116 In addition, combination of STING agonists

with PARP inhibitors may further promote antitumor immunity when cancer cells maintain the DDR pathway or lack cGAS, widening the scope of PARP inhibitor usage. ATM INHIBITOR Upon DNA

damage, ATM phosphorylates downstream mediators to regulate DDR and the cell cycle. Given the essential role of ATM in DSB repair, two ATM inhibitors (M3541, AZD01156) are under

investigation in combination with radiotherapy or chemotherapy (NCT03225105, NCT02588105). ATM deficiency leads to the accumulation of cytoplasmic DNA and induces type I IFNs in a

STING-dependent manner74; accordingly, the ATM inhibitor KU60019 induced cytoplasmic DNA accumulation and STING-dependent cytokine production in microglial cells.117 Another study on

pancreatic cancer cells observed TBK1 phosphorylation after KU60019 treatment.118 ATM-silenced pancreatic tumors showed increased CD8+ T cell infiltration and PD-L1 expression, suggesting

that ATM inhibition in tumors can induce antitumor immunity.118 ATM silencing in the tumor also sensitized the tumor to PD-L1 antibody or irradiation. However, cGAS and STING were found to

be dispensable for TBK1 phosphorylation after KU60019 treatment in this study.118 Thus, these early results have not yet resolved the question of whether cGAS is involved in ATM

inhibitor-induced immune responses. Future studies are needed to understand how ATM inhibitor-induced DNA damage is detected and whether antitumor immunity is critical for the therapeutic

effect of ATM inhibitors. CHECKPOINT KINASE INHIBITOR Checkpoint kinase 1 (CHK1) monitors DNA damage during DNA replication and regulates the cell cycle; thus, inhibition of CHK1 leads to

replication fork stalling and DSBs.119 Like other signals that cause DSBs, the CHK1 inhibitor prexasertib induced micronuclei in vitro.102 The cGAS-STING pathway was activated by these

micronuclei and induced expression of ISGs and PD-L1. In a lung cancer mouse model, CD8+ T cells were required for the full antitumor effect of prexasertib.102 Moreover, combination of

prexasertib with a PD-L1 antibody showed a synergistic antitumor effect. Cancer cells deficient in cGAS or STING were resistant to this combination therapy, suggesting that CHK1 inhibitors

enhance antitumor immunity by activating the cancer cell’s intrinsic cGAS-STING pathway. TOPOISOMERASE INHIBITOR Topoisomerase I and II relieve the torsion of DNA during DNA replication,

allowing the replication fork to proceed; inhibition of topoisomerase causes replication fork stalling, inducing DSBs and apoptosis.120 Cancer cell death is thought to be the major mechanism

of topoisomerase inhibition, but an early study showed that topoisomerase inhibition is linked to IRF3 activation.121 Recent studies suggest a role for cGAS and STING in topoisomerase

inhibitor-induced immune responses. Topoisomerase inhibitors such as teniposide, etoposide, camptothecin, doxorubicin, proflavine, and acriflavine induced cytosolic DNA in various cell

lines, activating the cGAS-STING pathway.61,64,122,123,124 Teniposide induced infiltration of CD8+ T cells to the tumor site and controlled tumor growth in a CD8+ T cell-dependent manner.125

This effect was markedly impaired when STING expression in tumor cells was silenced, indicating that tumor-intrinsic activation of the cGAS-STING pathway is critical for the therapeutic

effect of teniposide.125 Additionally, teniposide provided a synergistic effect when combined with PD-L1 antibody in mice implanted with tumor.125 Another study reports that the

topoisomerase inhibitor topotecan can also activate the cGAS-STING pathway in dendritic cells by inducing release of tumor DNA-containing exosomes from cancer cells.126 This antitumor effect

of topotecan was abrogated in STING-deficient mice, suggesting that cGAS/STING-mediated immune signaling was essential for the therapeutic effect of topotecan.126 Altogether, these reports

show that topoisomerase inhibitors can activate the cGAS-STING pathway in cancer cells and/or immune cells to enhance antitumor immune responses. Several studies suggested alternative

mechanisms for topoisomerase inhibition-induced immune responses. An early study reported that doxorubicin activates TLR3 in cancer cells to induce ISGs, which was critical for the

therapeutic effect.127 A more recent study showed that cGAS is essential for a high level of IFNβ induction in doxorubicin-treated cancer cells while a low level of IFNβ is still induced in

a ATM-dependent manner.124 Another study also suggested that etoposide induces IFNβ in a cGAS-independent but STING-dependent manner; PARP-1 and ATM detected DNA damage and induce a

non-canonical STING signaling complex to enhance NF-κB activation in several human cell lines.128 Future investigations on the role of the cGAS-STING pathway and other immune signaling

pathways in preclinical tumor models will refine our understanding of antitumor immune responses caused by topoisomerase inhibition. DNA CROSSLINKING AGENT Crosslinking agents form covalent

bonds with nucleophilic substrates, preferably a guanine base of DNA, and generate various DNA adducts or crosslinks.129 These types of DNA damage halt replication forks, inducing DSBs.

Crosslinking agents have been reported to be immunogenic and rely on CD8+ T cells for their therapeutic effect.130,131 More recently, crosslinking agents such as cisplatin, mitomycin C, and

mafosfamide were shown to induce cytosolic DNA and ISG expression in various cancer cells.85,132,133,134,135 ISG induction was increased in the absence of TREX1, suggesting cGAS

involvement.132 In the cytosolic fraction of cisplatin-treated cells, cGAS was bound to histone H3, indicating the interaction of cGAS with chromatin released from the nucleus.133 Moreover,

cGAS and STING were required for induction of ISGs by crosslinking agents.85,132,133,135 DNA crosslinking agents upregulated PD-L1 expression on cancer cells, and combining anti-PD-L1,

anti-PD-1, or anti-CTLA-4 with cisplatin gave a synergistic effect in treating several tumor models.133,134,136 Altogether, these studies show that cGAS promotes an antitumor effect by

detecting DNA damage caused by crosslinking agents. The immunomodulatory function of crosslinking agents provides a scientific rationale to combine them with other immunotherapies.

ANTIMETABOLITE Antimetabolite cancer therapies interfere with DNA replication; one of their targets is ribonucleotide reductase, which generates building blocks of DNA. Inhibiting

ribonucleotide reductase with hydroxyurea halts replication forks and causes DSBs.137 Hydroxyurea-induced DNA damage upregulates ISG expression in BRCA1-deficient breast cancer cells in a

cGAS/STING-dependent manner.133 In addition, hydroxyurea treatment increased PD-L1 expression on cancer cells, suggesting that the combination of antimetabolite drugs and immune checkpoint

inhibitors may show a synergistic effect. In this regard, the antimetabolite drug 5-fluorouracil showed a synergistic antitumor effect when combined with cGAMP treatment.138 Moreover,

combining cGAMP treatment reduced the toxicity of 5-fluorouracil, as shown by reduced intestinal damages, suggesting that combination therapies may have additional advantages over

mono-chemotherapy.138 Several clinical trials are ongoing to determine the combination effect of pembrolizumab, 5-fluorouracil, and cisplatin (NCT02494583, NCT03189719).

MICROTUBULE-TARGETING DRUG Blocking mitosis was one of the earliest strategies to interfere with cancer cell proliferation. Several microtubule inhibitors such as paclitaxel (Taxol)

interfere with chromosome segregation and induce mitotic arrest followed by apoptosis139; however, the in vivo contribution of mitotic arrest in the therapeutic effect remains controversial

as inhibitors targeting other mitotic processes were not as effective as microtubule-targeting drugs.140 At lower concentrations, paclitaxel causes chromosome mis-segregation, which leads to

micronuclei formation.139 Recent studies found that micronuclei induced by nocodazole or paclitaxel co-localizes with cGAS to induce the expression of downstream cytokines.63,141 Given our

recent knowledge regarding cGAS activation by micronuclei, activation of cGAS by microtubule-targeting drugs has the potential to induce antitumor immunity.30 In addition, the cGAS-STING

pathway may have a direct role in promoting cell death via anti-microtubule drugs. cGAS activation by paclitaxel induced type I IFNs and TNFα in breast cancer cell lines thereby driving

other cells to apoptosis in a paracrine manner; mechanistically, these cytokines induced the pro-apoptotic regulator Noxa to promote mitochondrial outer membrane permeabilization (MOMP).141

High doses of paclitaxel predominantly induce mitotic arrest rather than the micronuclei formation.68,142 In another study, paclitaxel-induced mitotic arrest activated cGAS and induced slow

phosphorylation of IRF3 that accelerated MOMP.68 Consistently, high levels of cGAS expression in non-small cell lung cancer correlated with prolonged survival for paclitaxel-treated

patients.68 In the human tumor xenograft model using immunocompromised mice, the antitumor effect of paclitaxel depended on the expression of cGAS or STING in cancer cells.68,141 Future

studies of antitumor immunity and apoptosis in paclitaxel-treated immunocompetent mouse models will help us design additional therapeutic strategies using microtubule-targeting drugs. FUTURE

PERSPECTIVES It is now clear that classic cancer therapies have immune-modulating functions; furthermore, the antitumor immunity was essential for the therapeutic effect of several classic

therapies in preclinical studies. These new findings suggest that classic cancer therapies are not merely cytotoxic treatments. The cGAS-STING pathway mediated the interplay between the

cytotoxic effect and immune stimulation by detecting DNA damage-induced micronuclei or cytoplasmic chromatin fragments and promoting antitumor immune responses. The newly discovered role of

classic cancer therapies as immune stimulants provides insights into designing therapeutic strategies. For example, the immune-stimulating ability of chemotherapy drugs in development can be

monitored together with their cytotoxicity. Chemotherapy drugs that have a better ability in inducing micronuclei formation may have more clinical benefits by activating cGAS and promoting

antitumor immunity. New chemotherapy “cocktails” can also be designed to maximize genome instability and the immunostimulatory effect. Furthermore, classic therapies can be combined with

immunotherapies to enhance antitumor immunity. Combining classic therapies with immune checkpoint blockade showed synergistic antitumor effects in multiple preclinical tumor models and

clinical trials.96,102,106,111,136 STING agonists further enhanced the antitumor immunity when combined with classic therapies.94,138 Moreover, several studies suggested that activation of

the cGAS-STING pathway has additional benefits in promoting immunostimulatory effects of chemotherapy drugs while reducing toxicity.68,138,141 It will be interesting to compare the

therapeutic effects of different combination therapies and look into their mechanisms of action. Studies of the cGAS-STING pathway in tumors have also led to new findings about the pathway.

The canonical cGAS-STING pathway induces autophagy and IRF3- and NF-κB-mediated cytokine expression. In addition to the canonical NF-κB pathway, non-canonical NF-κB pathway involving p100

and RelB was activated by cGAS and STING. Canonical NF-κB pathway was required for the therapeutic effect of radiotherapy whereas non-canonical NF-κB pathway was inhibitory.143 Moreover,

persistent activation of non-canonical NF-κB pathway in cancer cells with highly unstable genomes promoted metastasis due to chronic inflammation.89 In addition, new studies found

non-canonical cGAS and STING pathways that were independent of each other. Nuclear cGAS interfered with DDR by binding to the DNA repair enzyme PARP1 or compacting DNA independently of

STING.67,75 The DDR pathway involving PARP-1 and ATM led to formation of a STING signaling complex that includes p53 and the E3 ubiquitin ligase TRAF6 to induce cytokines independently of

cGAS; unlike canonical STING activation, this novel complex predominantly activated the NF-κB pathway.128 New findings in signaling and regulation of the cGAS-STING pathway will allow us to

utilize diverse methods to operate this pathway for cancer therapy. For example, specific inhibitors for the non-canonical NF-κB pathway enhanced the antitumor effect of radiotherapy.143 The

cGAS-STING pathway itself has numerous antitumor roles: promoting senescence in premalignant cells, inducing spontaneous antitumor immunity, and responding to classic cancer therapies.

Consistently, acute activation of the cGAS-STING pathway provides an antitumor effect; however, chronic inflammation by persistent and spontaneous activation of STING may promote tumor

growth and metastasis. In this regard, the presence of STING and downstream NF-κB signaling in astrocytes and breast cancer cells increased metastasis of brain and breast tumors,

respectively.48,89 Moreover, STING-induced inflammation promoted inflammation-driven tumorigenesis.83 STING activation also induced a negative feedback loop that downregulated immune

responses. Spontaneous activation of STING by tumor implantation induced indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase, which suppressed antitumor immunity.144 STING activation by radiotherapy induced TREX1

and recruited myeloid-derived suppressor cells to suppress immune responses.95,145 Such immunosuppression can be overcome by regulating the dose and frequency of radiotherapy or by combining

with other immunotherapies. Although acute activation of the cGAS-STING pathway predominantly induces antitumor immune responses, the protumor functions of the pathway should be considered

during cancer treatments. Further evaluations of the stage of cancer, clinical dose, frequency, and duration are needed to optimize the antitumor effect of the cGAS-STING pathways while

minimizing chronic inflammation and immunosuppression. REFERENCES * Faguet, G. B. A brief history of cancer: age-old milestones underlying our current knowledge database. _Int. J. Cancer_

136, 2022–2036 (2015). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Burnet, F. M. The concept of immunological surveillance. _Prog. Exp. Tumor Res._ 13, 1–27 (1970). Article CAS PubMed Google

Scholar * Ehrlich, P. Ueber den jetzigen stand der Karzinomforschung Nederlandsch Tijdschrift voor Geneeskunde. _Ned. Tijdschr. Geneeskd_ 5, 273–290 (1909). Google Scholar * Anichini, A.

et al. An expanded peripheral T cell population to a cytotoxic T lymphocyte (CTL)-defined, melanocyte-specific antigen in metastatic melanoma patients impacts on generation of

peptide-specific CTLs but does not overcome tumor escape from immune surveillance in metastatic lesions. _J. Exp. Med._ 190, 651–667 (1999). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google

Scholar * Lee, P. P. et al. Characterization of circulating T cells specific for tumor-associated antigens in melanoma patients. _Nat. Med._ 5, 677–685 (1999). Article CAS PubMed Google

Scholar * Sun, L., Wu, J., Du, F., Chen, X. & Chen, Z. J. Cyclic GMP-AMP synthase is a cytosolic DNA sensor that activates the type I interferon pathway. _Science_ 339, 786–791 (2013).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Wu, J. et al. Cyclic GMP-AMP is an endogenous second messenger in innate immune signaling by cytosolic DNA. _Science_ 339, 826–830 (2013). Article

CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Zhang, X. et al. Cyclic GMP-AMP containing mixed phosphodiester linkages is an endogenous high-affinity ligand for STING. _Mol. Cell_ 51, 226–235 (2013).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Ishikawa, H. & Barber, G. N. STING is an endoplasmic reticulum adaptor that facilitates innate immune signalling. _Nature_ 455, 674–678 (2008).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Sun, W. et al. ERIS, an endoplasmic reticulum IFN stimulator, activates innate immune signaling through dimerization. _Proc. Natl.

Acad. Sci. USA_ 106, 8653–8658 (2009). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Zhong, B. et al. The adaptor protein MITA links virus-sensing receptors to IRF3 transcription

factor activation. _Immunity_ 29, 538–550 (2008). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Shi, H., Wu, J., Chen, Z. J. & Chen, C. Molecular basis for the specific recognition of the

metazoan cyclic GMP-AMP by the innate immune adaptor protein STING. _Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA_ 112, 8947–8952 (2015). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Ishikawa, H.,

Ma, Z. & Barber, G. N. STING regulates intracellular DNA-mediated, type I interferon-dependent innate immunity. _Nature_ 461, 788–792 (2009). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google

Scholar * Fitzgerald, K. A. et al. IKKepsilon and TBK1 are essential components of the IRF3 signaling pathway. _Nat. Immunol._ 4, 491–496 (2003). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar *

Sharma, S. et al. Triggering the interferon antiviral response through an IKK-related pathway. _Science_ 300, 1148–1151 (2003). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Chen, Q., Sun, L.

& Chen, Z. J. Regulation and function of the cGAS-STING pathway of cytosolic DNA sensing. _Nat. Immunol._ 17, 1142–1149 (2016). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Gao, D. et al.

Cyclic GMP-AMP synthase is an innate immune sensor of HIV and other retroviruses. _Science_ 341, 903–906 (2013). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Hansen, K. et al. Listeria

monocytogenes induces IFNbeta expression through an IFI16-, cGAS- and STING-dependent pathway. _EMBO J._ 33, 1654–1666 (2014). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Li, X.

D. et al. Pivotal roles of cGAS-cGAMP signaling in antiviral defense and immune adjuvant effects. _Science_ 341, 1390–1394 (2013). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Gui, X. et al.

Autophagy induction via STING trafficking is a primordial function of the cGAS pathway. _Nature_ 567, 262–266 (2019). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Liu, D. et al. STING directly

activates autophagy to tune the innate immune response. _Cell Death Differ._ 26, 1735–1749 (2019). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Li, X. et al. Cyclic GMP-AMP synthase is activated

by double-stranded DNA-induced oligomerization. _Immunity_ 39, 1019–1031 (2013). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Zhang, X. et al. The cytosolic DNA sensor cGAS forms an oligomeric

complex with DNA and undergoes switch-like conformational changes in the activation loop. _Cell Rep._ 6, 421–430 (2014). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Gao, D. et

al. Activation of cyclic GMP-AMP synthase by self-DNA causes autoimmune diseases. _Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA_ 112, E5699–E5705 (2015). CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Gray,

E. E., Treuting, P. M., Woodward, J. J. & Stetson, D. B. Cutting edge: cGAS is required for lethal autoimmune disease in the Trex1-deficient mouse model of Aicardi-Goutieres syndrome.

_J. Immunol._ 195, 1939–1943 (2015). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Crow, Y. J. et al. Mutations in the gene encoding the 3′-5′ DNA exonuclease TREX1 cause Aicardi-Goutieres

syndrome at the AGS1 locus. _Nat. Genet._ 38, 917–920 (2006). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Liu, Y. et al. Activated STING in a vascular and pulmonary syndrome. _N. Engl. J. Med._

371, 507–518 (2014). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Iracheta-Vellve, A. et al. Endoplasmic reticulum stress-induced hepatocellular death pathways mediate liver

injury and fibrosis via stimulator of interferon genes. _J. Biol. Chem._ 291, 26794–26805 (2016). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Kerur, N. et al. cGAS drives

noncanonical-inflammasome activation in age-related macular degeneration. _Nat. Med._ 24, 50–61 (2018). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * King, K. R. et al. IRF3 and type I interferons

fuel a fatal response to myocardial infarction. _Nat. Med._ 23, 1481–1487 (2017). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Penn, I. Tumors of the immunocompromised patient.

_Annu. Rev. Med._ 39, 63–73 (1988). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Swann, J. B. & Smyth, M. J. Immune surveillance of tumors. _J. Clin. Invest._ 117, 1137–1146 (2007). Article

CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Harlin, H. et al. Chemokine expression in melanoma metastases associated with CD8+ T-cell recruitment. _Cancer Res._ 69, 3077–3085 (2009).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Diamond, M. S. et al. Type I interferon is selectively required by dendritic cells for immune rejection of tumors. _J. Exp. Med._ 208, 1989–2003

(2011). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Fuertes, M. B. et al. Host type I IFN signals are required for antitumor CD8+ T cell responses through CD8{alpha}+ dendritic

cells. _J. Exp. Med._ 208, 2005–2016 (2011). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Woo, S. R. et al. STING-dependent cytosolic DNA sensing mediates innate immune

recognition of immunogenic tumors. _Immunity_ 41, 830–842 (2014). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Demaria, O. et al. STING activation of tumor endothelial cells

initiates spontaneous and therapeutic antitumor immunity. _Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA_ 112, 15408–15413 (2015). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Marcus, A. et al.

Tumor-derived cGAMP triggers a STING-mediated interferon response in non-tumor cells to activate the NK cell response. _Immunity_ 49, 754–763 (2018). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central

Google Scholar * Schadt, L. et al. Cancer-cell-intrinsic cGAS expression mediates tumor immunogenicity. _Cell Rep._ 29, 1236–1248 (2019). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Lahey, L.

J. et al. The LRRC8A:C heteromeric channel is a cGAMP transporter and the dominant cGAMP importer in human vasculature cells. _bioRxiv_ https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.02.13.948273 (2020). *

Ablasser, A. et al. Cell intrinsic immunity spreads to bystander cells via the intercellular transfer of cGAMP. _Nature_ 503, 530–534 (2013). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google

Scholar * Luteijn, R. D. et al. SLC19A1 transports immunoreactive cyclic dinucleotides. _Nature_ 573, 434–438 (2019). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Ritchie, C.,

Cordova, A. F., Hess, G. T., Bassik, M. C. & Li, L. SLC19A1 is an importer of the immunotransmitter cGAMP. _Mol. Cell_ 75, 372–381 (2019). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google

Scholar * Zhou, C. et al. Transfer of cGAMP into bystander cells via LRRC8 volume-regulated anion channels augments STING-mediated interferon responses and anti-viral immunity. _Immunity_

52, 767–781 (2020). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Zhou, Y. et al. Blockade of the phagocytic receptor MerTK on tumor-associated macrophages enhances P2X7R-dependent STING

activation by tumor-derived cGAMP. _Immunity_ 52, 357–373 (2020). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Grivennikov, S. I., Greten, F. R. & Karin, M. Immunity, inflammation, and

cancer. _Cell_ 140, 883–899 (2010). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Ahn, J. et al. Inflammation-driven carcinogenesis is mediated through STING. _Nat. Commun._ 5,

5166 (2014). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Chen, Q. et al. Carcinoma-astrocyte gap junctions promote brain metastasis by cGAMP transfer. _Nature_ 533, 493–498 (2016). Article CAS

PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Coley, W. B. The treatment of inoperable sarcoma by bacterial toxins (the mixed toxins of the _Streptococcus erysipelas_ and the _Bacillus

prodigiosus_). _Proc. R. Soc. Med._ 3, 1–48 (1910). CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Ishida, Y., Agata, Y., Shibahara, K. & Honjo, T. Induced expression of PD-1, a novel

member of the immunoglobulin gene superfamily, upon programmed cell death. _EMBO J._ 11, 3887–3895 (1992). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Freeman, G. J. et al.

Engagement of the PD-1 immunoinhibitory receptor by a novel B7 family member leads to negative regulation of lymphocyte activation. _J. Exp. Med._ 192, 1027–1034 (2000). Article CAS PubMed

PubMed Central Google Scholar * Gong, J., Chehrazi-Raffle, A., Reddi, S. & Salgia, R. Development of PD-1 and PD-L1 inhibitors as a form of cancer immunotherapy: a comprehensive

review of registration trials and future considerations. _J. Immunother. Cancer_ 6, 8 (2018). Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Darvin, P., Toor, S. M., Sasidharan Nair, V.

& Elkord, E. Immune checkpoint inhibitors: recent progress and potential biomarkers. _Exp. Mol. Med._ 50, 165 (2018). Article CAS PubMed Central Google Scholar * Wang, H. et al. cGAS

is essential for the antitumor effect of immune checkpoint blockade. _Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA_ 114, 1637–1642 (2017). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Yum, S., Li,

M., Frankel, A. E. & Chen, Z. J. Roles of the cGAS-STING pathway in cancer immunosurveillance and immunotherapy. _Annu. Rev. Cancer Biol._ 3, 323–344 (2019). Article Google Scholar *

Corrales, L. et al. Direct activation of STING in the tumor microenvironment leads to potent and systemic tumor regression and immunity. _Cell Rep._ 11, 1018–1030 (2015). Article CAS

PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Li, L. et al. Hydrolysis of 2’3’-cGAMP by ENPP1 and design of nonhydrolyzable analogs. _Nat. Chem. Biol._ 10, 1043–1048 (2014). Article CAS PubMed

PubMed Central Google Scholar * Li, T. & Chen, Z. J. The cGAS-cGAMP-STING pathway connects DNA damage to inflammation, senescence, and cancer. _J. Exp. Med._ 215, 1287–1299 (2018).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Fenech, M. & Morley, A. A. Measurement of micronuclei in lymphocytes. _Mutat. Res._ 147, 29–36 (1985). Article CAS PubMed

Google Scholar * Fenech, M. et al. Molecular mechanisms of micronucleus, nucleoplasmic bridge and nuclear bud formation in mammalian and human cells. _Mutagenesis_ 26, 125–132 (2011).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Dou, Z. et al. Cytoplasmic chromatin triggers inflammation in senescence and cancer. _Nature_ 550, 402–406 (2017). Article CAS PubMed PubMed

Central Google Scholar * Harding, S. M. et al. Mitotic progression following DNA damage enables pattern recognition within micronuclei. _Nature_ 548, 466–470 (2017). Article CAS PubMed

PubMed Central Google Scholar * Mackenzie, K. J. et al. cGAS surveillance of micronuclei links genome instability to innate immunity. _Nature_ 548, 461–465 (2017). Article CAS PubMed

PubMed Central Google Scholar * Yang, H., Wang, H., Ren, J., Chen, Q. & Chen, Z. J. cGAS is essential for cellular senescence. _Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA_ 114, E4612–E4620 (2017). CAS

PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Gluck, S. et al. Innate immune sensing of cytosolic chromatin fragments through cGAS promotes senescence. _Nat. Cell Biol._ 19, 1061–1070 (2017).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Hatch, E. M., Fischer, A. H., Deerinck, T. J. & Hetzer, M. W. Catastrophic nuclear envelope collapse in cancer cell micronuclei.

_Cell_ 154, 47–60 (2013). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Liu, H. et al. Nuclear cGAS suppresses DNA repair and promotes tumorigenesis. _Nature_ 563, 131–136 (2018).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Zierhut, C. et al. The cytoplasmic DNA sensor cGAS promotes mitotic cell death. _Cell_ 178, 302–315 (2019). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central

Google Scholar * Crow, Y. J. & Rehwinkel, J. Aicardi-Goutieres syndrome and related phenotypes: linking nucleic acid metabolism with autoimmunity. _Hum. Mol. Genet._ 18, R130–R136

(2009). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Coquel, F. et al. SAMHD1 acts at stalled replication forks to prevent interferon induction. _Nature_ 557, 57–61 (2018).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Pokatayev, V. et al. RNase H2 catalytic core Aicardi-Goutieres syndrome-related mutant invokes cGAS-STING innate immune-sensing pathway in mice. _J.

Exp. Med._ 213, 329–336 (2016). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Ammann, A. J. & Hong, R. Autoimmune phenomena in ataxia telangiectasia. _J. Pediatr._ 78, 821–826

(1971). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Meyn, M. S. Ataxia-telangiectasia and cellular responses to DNA damage. _Cancer Res._ 55, 5991–6001 (1995). CAS PubMed Google Scholar *

Hartlova, A. et al. DNA damage primes the type I interferon system via the cytosolic DNA sensor STING to promote anti-microbial innate immunity. _Immunity_ 42, 332–343 (2015). Article

PubMed CAS Google Scholar * Jiang, H. et al. Chromatin-bound cGAS is an inhibitor of DNA repair and hence accelerates genome destabilization and cell death. _EMBO J._ 38, e102718 (2019).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Campisi, J. & d’Adda di Fagagna, F. Cellular senescence: when bad things happen to good cells. _Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol._ 8,

729–740 (2007). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Collado, M. et al. Tumour biology: senescence in premalignant tumours. _Nature_ 436, 642 (2005). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

* Braig, M. et al. Oncogene-induced senescence as an initial barrier in lymphoma development. _Nature_ 436, 660–665 (2005). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Chen, Z. et al. Crucial

role of p53-dependent cellular senescence in suppression of Pten-deficient tumorigenesis. _Nature_ 436, 725–730 (2005). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Coppe, J. P.,

Desprez, P. Y., Krtolica, A. & Campisi, J. The senescence-associated secretory phenotype: the dark side of tumor suppression. _Annu. Rev. Pathol._ 5, 99–118 (2010). Article CAS PubMed

PubMed Central Google Scholar * Xue, W. et al. Senescence and tumour clearance is triggered by p53 restoration in murine liver carcinomas. _Nature_ 445, 656–660 (2007). Article CAS

PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Kang, T. W. et al. Senescence surveillance of pre-malignant hepatocytes limits liver cancer development. _Nature_ 479, 547–551 (2011). Article CAS

PubMed Google Scholar * Ahn, J., Konno, H. & Barber, G. N. Diverse roles of STING-dependent signaling on the development of cancer. _Oncogene_ 34, 5302–5308 (2015). Article CAS

PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Zhu, Q. et al. Cutting edge: STING mediates protection against colorectal tumorigenesis by governing the magnitude of intestinal inflammation. _J.

Immunol._ 193, 4779–4782 (2014). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Xia, T., Konno, H., Ahn, J. & Barber, G. N. Deregulation of STING signaling in colorectal carcinoma constrains

DNA damage responses and correlates with tumorigenesis. _Cell Rep._ 14, 282–297 (2016). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Bu, Y., Liu, F., Jia, Q. A. & Yu, S. N. Decreased

expression of TMEM173 predicts poor prognosis in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. _PLoS ONE_ 11, e0165681 (2016). Article PubMed PubMed Central CAS Google Scholar * Nassour, J.

et al. Autophagic cell death restricts chromosomal instability during replicative crisis. _Nature_ 565, 659–663 (2019). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Mathew, R.,

Karantza-Wadsworth, V. & White, E. Role of autophagy in cancer. _Nat. Rev. Cancer_ 7, 961–967 (2007). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Bakhoum, S. F. et al.

Chromosomal instability drives metastasis through a cytosolic DNA response. _Nature_ 553, 467–472 (2018). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Delaney, G., Jacob, S.,

Featherstone, C. & Barton, M. The role of radiotherapy in cancer treatment: estimating optimal utilization from a review of evidence-based clinical guidelines. _Cancer_ 104, 1129–1137

(2005). Article PubMed Google Scholar * Mole, R. H. Whole body irradiation; radiobiology or medicine? _Br. J. Radiol._ 26, 234–241 (1953). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Lee, Y.

et al. Therapeutic effects of ablative radiation on local tumor require CD8+ T cells: changing strategies for cancer treatment. _Blood_ 114, 589–595 (2009). Article CAS PubMed PubMed

Central Google Scholar * Burnette, B. C. et al. The efficacy of radiotherapy relies upon induction of type I interferon-dependent innate and adaptive immunity. _Cancer Res._ 71, 2488–2496

(2011). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Deng, L. et al. STING-dependent cytosolic DNA sensing promotes radiation-induced type I interferon-dependent antitumor

immunity in immunogenic tumors. _Immunity_ 41, 843–852 (2014). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Vanpouille-Box, C. et al. DNA exonuclease Trex1 regulates

radiotherapy-induced tumour immunogenicity. _Nat. Commun._ 8, 15618 (2017). Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Deng, L. et al. Irradiation and anti-PD-L1 treatment

synergistically promote antitumor immunity in mice. _J. Clin. Invest._ 124, 687–695 (2014). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Shevtsov, M., Sato, H., Multhoff, G. &

Shibata, A. Novel approaches to improve the efficacy of immuno-radiotherapy. _Front. Oncol._ 9, 156 (2019). Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Mihich, E. Combined effects of

chemotherapy and immunity against leukemia L1210 in DBA-2 mice. _Cancer Res._ 29, 848–854 (1969). CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Mihich, E. Modification of tumor regression by immunologic

means. _Cancer Res._ 29, 2345–2350 (1969). CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Zitvogel, L., Kepp, O. & Kroemer, G. Immune parameters affecting the efficacy of chemotherapeutic regimens.

_Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol._ 8, 151–160 (2011). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Pantelidou, C. et al. PARP inhibitor efficacy depends on CD8(+) T-cell recruitment via intratumoral STING

pathway activation in BRCA-deficient models of triple-negative breast cancer. _Cancer Discov._ 9, 722–737 (2019). Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Sen, T. et al. Targeting

DNA damage response promotes antitumor immunity through STING-mediated T-cell activation in small cell lung cancer. _Cancer Discov._ 9, 646–661 (2019). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central

Google Scholar * Miki, Y. et al. A strong candidate for the breast and ovarian cancer susceptibility gene BRCA1. _Science_ 266, 66–71 (1994). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar *

Sonnenblick, A., de Azambuja, E., Azim, H. A. Jr. & Piccart, M. An update on PARP inhibitors–moving to the adjuvant setting. _Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol._ 12, 27–41 (2015). Article CAS

PubMed Google Scholar * Chabanon, R. M. et al. PARP inhibition enhances tumor cell-intrinsic immunity in ERCC1-deficient non-small cell lung cancer. _J. Clin. Invest._ 129, 1211–1228

(2019). Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Shen, J. et al. PARPi triggers the STING-dependent immune response and enhances the therapeutic efficacy of immune checkpoint

blockade independent of BRCAness. _Cancer Res._ 79, 311–319 (2019). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Wang, Z. et al. Niraparib activates interferon signaling and potentiates anti-PD-1

antibody efficacy in tumor models. _Sci. Rep._ 9, 1853 (2019). Article PubMed PubMed Central CAS Google Scholar * Reislander, T. et al. BRCA2 abrogation triggers innate immune

responses potentiated by treatment with PARP inhibitors. _Nat. Commun._ 10, 3143 (2019). Article PubMed PubMed Central CAS Google Scholar * Coleman, R. L. et al. Rucaparib maintenance

treatment for recurrent ovarian carcinoma after response to platinum therapy (ARIEL3): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. _Lancet_ 390, 1949–1961 (2017). Article

CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Mirza, M. R. et al. Niraparib maintenance therapy in platinum-sensitive, recurrent ovarian cancer. _N. Engl. J. Med._ 375, 2154–2164 (2016).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Jiao, S. et al. PARP inhibitor upregulates PD-L1 expression and enhances cancer-associated immunosuppression. _Clin. Cancer Res._ 23, 3711–3720

(2017). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Konstantinopoulos, P. A. et al. Single-arm phases 1 and 2 trial of Niraparib in combination with Pembrolizumab in patients

with recurrent platinum-resistant ovarian carcinoma. _JAMA Oncol._ 5, 1141–1149 (2019). Article PubMed Central PubMed Google Scholar * Vinayak, S. et al. Open-label clinical trial of

Niraparib combined with Pembrolizumab for treatment of advanced or metastatic triple-negative breast cancer. _JAMA Oncol._ 5, 1132–1140 (2019). Article PubMed Central PubMed Google

Scholar * Schoonen, P. M. et al. Premature mitotic entry induced by ATR inhibition potentiates olaparib inhibition-mediated genomic instability, inflammatory signaling and cytotoxicity in

BRCA2-deficient cancer cells. _Mol. Oncol._ 13, 2422–2440 (2019). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * de Queiroz, N., Xia, T., Konno, H. & Barber, G. N. Ovarian

cancer cells commonly exhibit defective STING signaling which affects sensitivity to viral oncolysis. _Mol. Cancer Res._ 17, 974–986 (2019). Article PubMed Google Scholar * Ding, L. et

al. PARP inhibition elicits STING-dependent antitumor immunity in Brca1-deficient ovarian cancer. _Cell Rep._ 25, 2972–2980 (2018). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar *

Song, X., Ma, F. & Herrup, K. Accumulation of cytoplasmic DNA due to ATM deficiency activates the microglial viral response system with neurotoxic consequences. _J. Neurosci._ 39,

6378–6394 (2019). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Zhang, Q. et al. Inhibition of ATM increases interferon signaling and sensitizes pancreatic cancer to immune

checkpoint blockade therapy. _Cancer Res._ 79, 3940–3951 (2019). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Forment, J. V., Blasius, M., Guerini, I. & Jackson, S. P.

Structure-specific DNA endonuclease Mus81/Eme1 generates DNA damage caused by Chk1 inactivation. _PLoS ONE_ 6, e23517 (2011). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Pommier,

Y. Topoisomerase I inhibitors: camptothecins and beyond. _Nat. Rev. Cancer_ 6, 789–802 (2006). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Kim, T. et al. Activation of interferon regulatory

factor 3 in response to DNA-damaging agents. _J. Biol. Chem._ 274, 30686–30689 (1999). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Pepin, G. et al. Topoisomerase 1 inhibition promotes cyclic

GMP-AMP synthase-dependent antiviral responses. _MBio_ 8, e01611–17 (2017). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Pepin, G. et al. Activation of cGAS-dependent antiviral

responses by DNA intercalating agents. _Nucleic Acids Res._ 45, 198–205 (2017). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Luthra, P. et al. Topoisomerase II inhibitors induce DNA

damage-dependent interferon responses circumventing Ebola virus immune evasion. _MBio_ 8, e00368–17 (2017). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Wang, Z. et al. cGAS/STING

axis mediates a topoisomerase II inhibitor-induced tumor immunogenicity. _J. Clin. Invest._ 130, 4850–4862 (2019). Article Google Scholar * Kitai, Y. et al. DNA-containing exosomes

derived from cancer cells treated with Topotecan activate a STING-dependent pathway and reinforce antitumor immunity. _J. Immunol._ 198, 1649–1659 (2017). Article CAS PubMed Google

Scholar * Sistigu, A. et al. Cancer cell-autonomous contribution of type I interferon signaling to the efficacy of chemotherapy. _Nat. Med._ 20, 1301–1309 (2014). Article CAS PubMed

Google Scholar * Dunphy, G. et al. Non-canonical activation of the DNA sensing adaptor STING by ATM and IFI16 mediates NF-kappaB signaling after nuclear DNA damage. _Mol. Cell_ 71, 745–760

(2018). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Rycenga, H. B. & Long, D. T. The evolving role of DNA inter-strand crosslinks in chemotherapy. _Curr. Opin. Pharmacol._

41, 20–26 (2018). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Beyranvand Nejad, E. et al. Tumor eradication by cisplatin is sustained by CD80/86-mediated costimulation of CD8+ T

cells. _Cancer Res._ 76, 6017–6029 (2016). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Di Blasio, S. et al. Human CD1c(+) DCs are critical cellular mediators of immune responses induced by

immunogenic cell death. _Oncoimmunology_ 5, e1192739 (2016). Article PubMed PubMed Central CAS Google Scholar * Erdal, E., Haider, S., Rehwinkel, J., Harris, A. L. & McHugh, P. J. A

prosurvival DNA damage-induced cytoplasmic interferon response is mediated by end resection factors and is limited by Trex1. _Genes Dev._ 31, 353–369 (2017). Article CAS PubMed PubMed

Central Google Scholar * Parkes, E. E. et al. Activation of STING-dependent innate immune signaling by S-phase-specific DNA damage in breast cancer. _J. Natl. Cancer Inst._ 109, djw199

(2017). Article CAS Google Scholar * Grabosch, S. et al. Cisplatin-induced immune modulation in ovarian cancer mouse models with distinct inflammation profiles. _Oncogene_ 38, 2380–2393

(2019). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Gaston, J. et al. Intracellular STING inactivation sensitizes breast cancer cells to genotoxic agents. _Oncotarget_ 7, 77205–77224 (2016).

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Nolan, E. et al. Combined immune checkpoint blockade as a therapeutic strategy for BRCA1-mutated breast cancer. _Sci. Transl. Med._ 9,

eaal4922 (2017). Article PubMed PubMed Central CAS Google Scholar * Guarino, E., Salguero, I., Jimenez-Sanchez, A. & Guzman, E. C. Double-strand break generation under

deoxyribonucleotide starvation in _Escherichia coli_. _J. Bacteriol._ 189, 5782–5786 (2007). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Li, T. et al. Antitumor activity of cGAMP

via stimulation of cGAS-cGAMP-STING-IRF3 mediated innate immune response. _Sci. Rep._ 6, 19049 (2016). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Jordan, M. A. et al. Mitotic

block induced in HeLa cells by low concentrations of paclitaxel (Taxol) results in abnormal mitotic exit and apoptotic cell death. _Cancer Res._ 56, 816–825 (1996). CAS PubMed Google

Scholar * Komlodi-Pasztor, E., Sackett, D., Wilkerson, J. & Fojo, T. Mitosis is not a key target of microtubule agents in patient tumors. _Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol._ 8, 244–250 (2011).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Lohard, S. et al. STING-dependent paracriny shapes apoptotic priming of breast tumors in response to anti-mitotic treatment. _Nat. Commun._ 11, 259

(2020). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Mitchison, T. J., Pineda, J., Shi, J. & Florian, S. Is inflammatory micronucleation the key to a successful anti-mitotic

cancer drug? _Open Biol._ 7, 170182 (2017). Article PubMed PubMed Central CAS Google Scholar * Hou, Y. et al. Non-canonical NF-kappaB antagonizes STING sensor-mediated DNA sensing in

radiotherapy. _Immunity_ 49, 490–503 (2018). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Lemos, H. et al. STING promotes the growth of tumors characterized by low antigenicity

via IDO activation. _Cancer Res._ 76, 2076–2081 (2016). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Liang, H. et al. Host STING-dependent MDSC mobilization drives extrinsic

radiation resistance. _Nat. Commun._ 8, 1736 (2017). Article PubMed PubMed Central CAS Google Scholar * Xia, T., Konno, H. & Barber, G. N. Recurrent loss of STING signaling in

melanoma correlates with susceptibility to viral oncolysis. _Cancer Res._ 76, 6747–6759 (2016). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar Download references ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS We thank Jose

Cabrera for graphics assistance. Research in the Chen laboratory has been supported by grants from the NIH (P50AR070594, U01CA218422 and U54CA244719), the Cancer Prevention and Research

Institute of Texas (RP180725), and the Welch Foundation (I-1389). Z.J.C. is an investigator of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute (HHMI). AUTHOR INFORMATION AUTHORS AND AFFILIATIONS *

Department of Molecular Biology and Center for Inflammation Research, University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas, TX, 75390, USA Seoyun Yum, Minghao Li & Zhijian J. Chen *

Howard Hughes Medical Institute, Chevy Chase, MD, 20815, USA Zhijian J. Chen Authors * Seoyun Yum View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar *

Minghao Li View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Zhijian J. Chen View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google

Scholar CONTRIBUTIONS S.Y., M.L., and Z.J.C. wrote and revised the manuscript. CORRESPONDING AUTHOR Correspondence to Zhijian J. Chen. ETHICS DECLARATIONS COMPETING INTERESTS The authors

declare no competing interests. RIGHTS AND PERMISSIONS OPEN ACCESS This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing,

adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons

license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a

credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted

use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. Reprints and permissions ABOUT

THIS ARTICLE CITE THIS ARTICLE Yum, S., Li, M. & Chen, Z.J. Old dogs, new trick: classic cancer therapies activate cGAS. _Cell Res_ 30, 639–648 (2020).

https://doi.org/10.1038/s41422-020-0346-1 Download citation * Received: 30 March 2020 * Accepted: 08 May 2020 * Published: 15 June 2020 * Issue Date: August 2020 * DOI:

https://doi.org/10.1038/s41422-020-0346-1 SHARE THIS ARTICLE Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content: Get shareable link Sorry, a shareable link is not

currently available for this article. Copy to clipboard Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative