Quasi pd1ni single-atom surface alloy catalyst enables hydrogenation of nitriles to secondary amines

- Select a language for the TTS:

- UK English Female

- UK English Male

- US English Female

- US English Male

- Australian Female

- Australian Male

- Language selected: (auto detect) - EN

Play all audios:

ABSTRACT Hydrogenation of nitriles represents as an atom-economic route to synthesize amines, crucial building blocks in fine chemicals. However, high redox potentials of nitriles render

this approach to produce a mixture of amines, imines and low-value hydrogenolysis byproducts in general. Here we show that quasi atomic-dispersion of Pd within the outermost layer of Ni

nanoparticles to form a Pd1Ni single-atom surface alloy structure maximizes the Pd utilization and breaks the strong metal-selectivity relations in benzonitrile hydrogenation, by prompting

the yield of dibenzylamine drastically from ∼5 to 97% under mild conditions (80 °C; 0.6 MPa), and boosting an activity to about eight and four times higher than Pd and Pt standard catalysts,

respectively. More importantly, the undesired carcinogenic toluene by-product is completely prohibited, rendering its practical applications, especially in pharmaceutical industry. Such

strategy can be extended to a broad scope of nitriles with high yields of secondary amines under mild conditions. SIMILAR CONTENT BEING VIEWED BY OTHERS HIGHLY-EFFICIENT RUNI SINGLE-ATOM

ALLOY CATALYSTS TOWARD CHEMOSELECTIVE HYDROGENATION OF NITROARENES Article Open access 08 June 2022 SOLVENT-FREE SELECTIVE HYDROGENATION OF NITROAROMATICS TO AZOXY COMPOUNDS OVER CO SINGLE

ATOMS DECORATED ON NB2O5 NANOMESHES Article Open access 12 April 2024 EARTH-ABUNDANT NI-ZN NANOCRYSTALS FOR EFFICIENT ALKYNE SEMIHYDROGENATION CATALYSIS Article Open access 12 May 2025

INTRODUCTION Among nitrogen-containing chemicals, amines are important and ubiquitous in various biological active compounds1,2, and are also valuable building blocks for synthesis of

polymers, dyes, pharmaceuticals, agrochemicals, and fine chemicals in industry3,4,5,6,7. Compared with other functional compounds, synthesis of amines has received one of the most extensive

attentions in organic chemistry3,8. Several methods such as amination of aryl and alkyl halides9,10,11, reductive amination of aldehydes and ketones12,13, amination of alcohols7,14 and

hydroaminations of olefins6,15, have been developed to construct the carbon–nitrogen bonds for amines synthesis. However, these routes require either base additives or high cost, and also

produce heavy liquid wastes in general. Alternatively, hydrogenation of readily available nitriles using molecular hydrogen over heterogeneous16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23 and

homogeneous5,24,25,26 metal catalysts has been recognized as a more environmentally benign and atom-economic route to synthesis of these value-added amines. While, owing to the high redox

potentials of nitriles, this process often shows severe selectivity issues, and generally produces mixtures of primary, secondary, and tertiary amines, imines and low-value hydrogenolysis

by-products4,27, which makes this approach costly in the sequential products separation due to small differences in their boiling points28. In the case of hydrogenation of benzonitrile (BN),

the formation of by-product toluene (TOL) is completely undesirable, not only because it lowers the atom economy, but also due to that TOL is carcinogenic29, which can be fatal for the

applications of these contaminated benzylamine (BA) and dibenzylamine (DBA) in pharmaceutical industry. For examples, Pd catalysts often produce BA in majority, but also along with a

considerable amount of TOL production16,19,20. Pt catalysts show a very different catalytic behavior, by producing DBA as the major product instead, and also along with a few percentage of

TOL formation16,21,22. Transition metal Ni catalysts are also investigated, but show relatively lower hydrogenation activity even under much higher hydrogen pressures; therein, a mixture of

BA, DBA, and the N-benzylidenebenzylamine (DBI) are generally observed30,31. The nature of metal catalysts appears to be the crucial factor that governs the reaction selectivity4,28,32.

Alloying Pd with Ir was shown to be capable of tailoring the product selectivity to a large extend, but still generating an appreciable amount of toxic TOL by-product of ~8%32. Incorporation

of additives (such as ammonia, NaOH, HCl, acetic acid, NaH2PO4 et al.) is helpful to prompt primary amine formation19,28,31,33. However, such additive process would lead to equipment

corrosion issues and raise of the cost for products purification, in addition, the formation of toluene is still inevitable19. Recently, hydrogenation of nitriles using a supercritical

CO2/H2O biphasic solvent and transfer hydrogenation of nitriles with ammonia borane or HCOOH in triethylamine as hydrogen source were reported for selective hydrogenation of nitriles to

primary or secondary amines34,35,36,37, while these routes both suffer from high cost due to either the harsh operation pressure or the high cost of the hydrogen source (or solvent).

Therefore, it is still an urgent need to develop a heterogeneous catalyst to produce only one of these amines selectively along with complete inhibition of hydrocarbons by-product under a

mild and facile reaction condition. Among these protocols, direct hydrogenation of nitriles to secondary amines is particularly desirable, but much more challenging, because of the

involvement of complex reaction networks and strong metal-selectivity relations4,32,38. Inspired by maximized noble metal utilization in core-shell bimetallic catalysts and the unique

coordination and electronic environment in single-atom alloy (SAA) catalysts39,40,41,42,43,44,45, here we report that selective deposition of Pd on silica supported Ni NPs at low coverages

using atomic layer deposition (ALD) produces quasi atomically dispersed Pd within the outermost layer of Ni particles to form a core-shell like quasi Pd1Ni single-atom surface alloy (SASA)

structure as confirmed by detailed microscopic and spectroscopic characterization. The resulting isolated Pd atoms and the surrounding Ni atoms act in synergy, break the strong

metal-selectivity relations in hydrogenation of BN, and prompt the yield of DBA drastically from ~5 to 97% under mild conditions (80 °C; 0.6 MPa); meanwhile, the carcinogenic TOL by-product

is below the detection limit, rendering its practical applications, especially in pharmaceuticals46, e.g. penicillin47. In addition, the activity was also about eight and four times higher

than those of monometallic Pd and Pt catalysts, respectively. Theoretical calculations unveil that the strong synergy between isolated Pd atoms and Ni significantly extend the resident time

of BI intermediate on Pd1Ni surface, thus stimulating the exclusive formation of DBA. This method can be extended to a broad scope of nitriles to achieve secondary amines with high yields

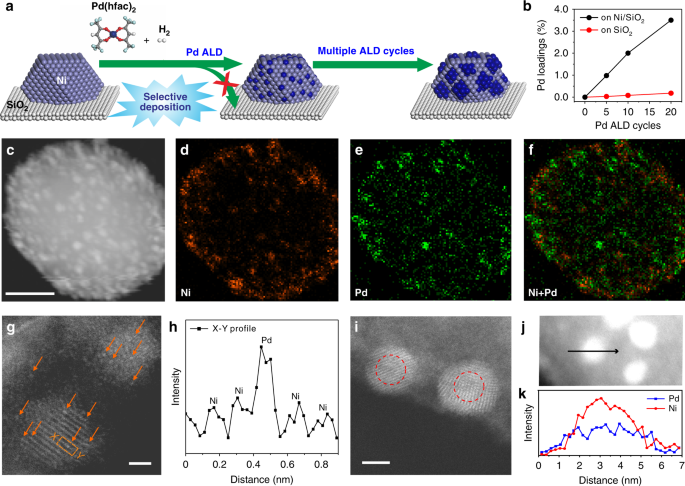

above 94% under mild conditions, shedding light for controlling the selectivity in hydrogenation of nitriles. RESULTS AND DISCUSSION SYNTHESIS AND MORPHOLOGY OF PDNI BIMETALLIC CATALYSTS A

set of PdNi/SiO2 bimetallic catalysts with different Pd dispersions were precisely fabricated using a method by combining wet chemistry and ALD (Supplementary Fig. 1). A Ni/SiO2 catalyst

with an average particle size of 3.4 ± 0.7 nm was first prepared using the deposition-precipitation (DP) method (Supplementary Fig. 2)48. After that, with the strategy of low-temperature

selective deposition for bimetallic NP synthesis we developed recently49,50,51, Pd ALD was executed on the Ni/SiO2 catalyst at 150 °C to deposit Pd selectively on the surface of Ni NPs

without any nucleation on SiO2 support (Fig. 1a)50. At low Pd coverages, the highly dispersed Pd atoms might become a part of Ni surface lattice to minimize the surface energies (the middle

of Fig. 1a). Varying the number of ALD cycles tailors the Pd coverage on Ni NPs precisely. The resulting samples are denoted as _x_Pd-Ni/SiO2, where _x_ represents the number of ALD cycles.

Inductively coupled plasma atomic emission spectroscopy (ICP-AES) analysis (Fig. 1b and Supplementary Table 1) and energy-dispersive spectroscopy (EDS) elemental mapping (Fig. 1c–f) both

unambiguously confirmed the selective deposition of Pd on Ni NPs. Figure 1g shows a representative aberration-corrected high-angle annular dark-field scanning transmission electron

microscopy (HAADF-STEM) image of 5Pd-Ni/SiO2. Due to the much larger Z value of Pd than Ni, brighter spots highlighted by the yellow arrows in Fig. 1g and Supplementary Fig. 3, along with

the intensity profile in Fig. 1h, suggest that Pd atoms were atomically dispersed on the partially oxidized Ni NPs, which might be caused by air exposure during sample transfer. On

20Pd-Ni/SiO2, large Pd ensembles (or even continuous shell) were formed on Ni NPs, as indicated by the brighter shell in Fig. 1i and the line profile analysis in Fig. 1j, k. CATALYTIC

PERFORMANCE Selective hydrogenation of BN was conducted in a batch reactor at 80 °C using ethanol as the solvent under a H2 pressure of 0.6 MPa. A Pd/SiO2 sample with a Pd particle size of

3.2 ± 0.3 nm (Supplementary Fig. 4) was first evaluated. It required ~10 h to complete the reaction (Fig. 2a). The selectivity of BA was about 74% at the earlier stage, but considerably

decreased with time. The selectivity of DBA and the undesired hydrogenolysis by-product TOL were about 5 and 21%, respectively, consistent with literature (Supplementary Table 2)16,19,20.

When conversion was above 90%, the selectivity of TOL increased rapidly to 36% at the expense of the BA, indicating the hydrogenolysis reaction of BA to TOL. Decreasing the reaction

temperature from 80 to 60 °C or increasing hydrogenation pressure to 1 MPa did not change the products distribution significantly (Supplementary Table 3). A Pt/SiO2 catalyst (Supplementary

Fig. 5), the well-documented catalyst to produce DBA16,21,22, was also evaluated under the same conditions. It was found that the reaction completed in 9 h (Fig. 2b) with a DBA selectivity

of only ~73%. The TOL selectivity was also as high as 11%, consistent with literature (Supplementary Table 2)16,21,22. On the 5Pd-Ni/SiO2 sample, the reaction proceeded much quicker, and

completed in only ~3 h (Fig. 2c). Very surprisingly, the distribution of products changed completely; therein DBA became the major product, with a selectivity as high as ~97% in the entire

range of BN conversions, leading to a high yield of DBA up to 97%. In contrast, BA was decreased sharply to only ~3%, and the undesired hydrogenolysis path to TOL was below the detection

limit in the entire range of conversion. More importantly, after the reaction was completed, prolonging the reaction to another 3 h did not alter the DBA selectivity considerably, much

better than Pd/SiO2 and Pt/SiO2 (Fig. 2a,b), indication of an effective inhibition of hydrogenolysis of amines to hydrocarbons. Increase of the reaction temperature to 120 °C or the H2

pressure to 1 MPa would reduce the DBA selectivity slightly, while TOL was still effectively prohibited in both cases (Supplementary Table 4). On the other hand, we found that variation of

solvents did not change the DBA selectivity considerably, different from the literature52, although the activity became slightly lower in non-alcoholic solvents (Supplementary Table 5). This

result suggests that the high DBA selectivity achieved on 5Pd-Ni/SiO2 catalyst is solely due to the synergy in Pd1Ni SASA, rather than the solvent effect. These robust catalytic behaviors

under different conditions render it convenient for practical operation in a large scale. Calculations of turnover frequencies (TOFs) reveal that the 5Pd-Ni/SiO2 sample exhibited a highest

TOF of 515 h−1, which was about eight and four times higher than Pd/SiO2 (64 h−1) and Pt/SiO2 (127 h−1), respectively, as shown in Fig. 2d. Moreover, the remarkable activity and selectivity

achieved on 5Pd-Ni/SiO2 SASA were both much superior than those Pd-, Pt-, Rh-, and Ir-based catalysts reported in literatures (Supplementary Table 2). To note that the conversion of BN was

about only 2.6% after 3 h on the Ni/SiO2 sample under the same reaction conditions (Supplementary Fig. 6). Recyclability of 5Pd-Ni/SiO2 was further evaluated, it was found that no

significant decay in both selectivity and activity was observed even after the catalyst was recycled for eight times without further calcination/reduction treatments in between (Fig. 2e),

indicating the absence of any poisoning or coking. STEM measurements of the recycled sample further confirmed the persistence of the high dispersion of Pd on Ni particles in majority as that

in the fresh samples (Supplementary Fig. 7). Accordingly, 5Pd-Ni/SiO2 catalyst was highly active and stable during BN hydrogenation, thereby exhibiting potential practical applications,

especially in pharmaceuticals46, e.g. penicillin47. Lennon et al. proposed that the TOL formation stems from hydrogenolysis of BA on Pd catalyst, which takes place independently from BN

hydrogenation20. To get a better understanding of the inhibition of TOL formation on 5Pd-Ni/SiO2 in BN hydrogenation, the BA hydrogenolysis reaction was further performed on these three

samples under the same conditions. It was found that BA hydrogenolysis was negligible on 5Pd-Ni/SiO2, but much facile on Pd/SiO2 and Pt/SiO2 (Fig. 2f), unambiguously confirming the effective

inhibition of the TOL formation. Increasing the Pd coverage on Ni decreased the TOF and the yield of DBA considerably by forming more BA product (Supplementary Fig. 8). For instance, on

20Pd-Ni/SiO2, the yield of DBA reduced to 77%, along with a BA yield of 21%. According to the catalytic behavior of Pd/SiO2 (Fig. 2a), the increase of the BA yield on 20Pd-Ni/SiO2 is

attributed to the formation of large Pd ensembles at high converges (Fig. 1), providing solid evidence that isolation of Pd with Ni plays the key role for the exclusive DBA formation on

5Pd-Ni/SiO2. However, the TOL formation was still trivial on all PdNi samples (Supplementary Figs. 8 and 9). Besides above, we found that selective hydrogenation of BN over _x_Pt-Ni/SiO2

(_x_ = 1, 3) bimetallic catalysts, synthesized in a similar manner with _x_Pd-Ni/SiO2, also showed remarkable activity improvements and efficient inhibition of TOL formation (Supplementary

Table 6). However, over these PtNi bimetallic catalysts, DBI was the major product (>70% selectivity) instead, sharply different from _x_Pd-Ni/SiO2. STRUCTURAL CHARACTERIZATION OF PDNI

BIMETALLIC CATALYSTS To establish structure-activity relations, in situ X-ray adsorption fine-structure (XAFS) measurements were first performed on the _x_Pd-Ni/SiO2 samples (_x_ = 5, 10,

and 20) at the Pd _K_-edge to investigate the detailed coordination environments of Pd in PdNi bimetallic NPs (Supplementary Figs. 10–12 and Supplementary Note 1). Fourier transforms of the

extended X-ray absorption fine structure (EXAFS) spectra of various samples in the real space are shown in Fig. 3a. After in situ H2 reduction at 150 °C, the EXAFS spectrum of 5Pd-Ni/SiO2

exhibited a dominant peak at 2.12 Å, mainly attributed to Pd-Ni coordination53,54. EXAFS curve fittings revealed that the Pd-Ni coordination is the dominant one with a coordination number

(CN) of 5.5, while the Pd-Pd coordination has a minor contribution with a CN of only 1.2 (Supplementary Figs. 11a and 12a, and Supplementary Table 7), suggesting that Pd atoms are atomically

dispersed in majority, in line with the HAADF-STEM observation (Fig. 1g). When the Pd atoms were uniformly distributed over both the surface and the bulk of Ni NPs, it is expected that the

Pd-Ni CN will be significantly higher than the average CN for surface atoms40,55. In our case, the surface Ni atoms in a 3.4-nm Ni NP have an average Ni–Ni CN of 7.8, according to the

cubic-octahedral cluster model56. Thus the lower CN of 5.5 for Pd–Ni suggests that the isolated Pd atoms were within the outermost layer of Ni particles in majority to form a core-shell like

quasi Pd1Ni SASA structure (the inset of Fig. 3a). To note that this structure with maximized Pd utilization, is sharply different from those SAAs in literature where the isolated secondary

metal atoms (B) are rather uniformly dispersed within the primary metal (A) particles with a large CN of A–B bond (often greater than 9)40,45,55,57. As increasing the Pd coverage, the peak

splits into two peaks at 2.15 and 2.52 Å, assigned to the Pd–Ni and Pd–Pd coordinations, respectively53,54. EXAFS curve fittings showed that the CNs of Pd-Ni coordination decreased to 4.3

and 2.7, while the Pd-Pd coordination increased to 3.6 and 6.6 for 10Pd-Ni/SiO2 and 20Pd–Ni/SiO2, respectively (Supplementary Figs. 11b, c, and 12b, c, and Supplementary Table 7). These

results describe the evolution of Pd species on Ni from quasi atomically dispersed Pd atoms to large Pd ensembles or even continuous Pd shell, consistent excellently with the STEM

observation (Fig. 1). To further explore the surface structure of PdNi bimetallic NPs, in situ diffuse reflectance infrared Fourier transform spectroscopy (DRIFTS) CO chemisorption

measurements were also performed on these samples, since CO is a well-known sensitive probe of Pd ensemble structures50,58,59,60,61,62. In this work, after CO exposure, O2 purging was

employed to remove chemisorbed CO on Ni, so that the CO on Pd can be illustrated individually (See Supplementary Fig. 13 and Supplementary Note 2 for details). As shown in Fig. 3b, on

5Pd–Ni/SiO2, the dominant peak at 2092 cm−1, assigned to the linear CO on Pd, was much stronger than the bridge-bonded CO peak at 1975 cm−1, thus again implying that Pd was isolated by the

surrounding Ni atoms in majority50,60,63, which agrees excellently with the EXAFS results in Fig. 3a and the STEM observation (Fig. 1g). As increase of Pd ALD cycles, the bridge-bonded CO

peak developed aggressively, clearly demonstrating the formation of large Pd ensembles or continuous Pd shell on the surface of Ni NPs in these two samples50. In situ X-ray photoemission

spectroscopy (XPS) measurements in the Pd 3_d_ region disclosed a strong electronic interaction between Pd and Ni (Fig. 3c). On 5Pd–Ni/SiO2, we observed a remarkable upwards shift of Pd 3_d_

binding energy by 0.7 eV with respect to that of Pd/SiO2, which is attributed to the charge transfer between Pd and Ni64,65,66. The upwards shift gradually became less pronounced as

increasing the Pd coverage, implying the surface electronic structure was tending to pure Pd, in line with literature50,66,67,68. In brief, the remarkable activity improvements and

selectivity tailoring in Fig. 2 and Supplementary Figs. 8 and 9 are attributed to the ensemble and electronic structure of Pd on Ni. THEORETICAL INSIGHT OF HYDROGENATION OF BN ON METALS

Adamczyk et al. very recently reported detailed calculations of hydrogenation of acetonitrile on Pd and Co catalysts69,70,71. However, to our knowledge, theoretical calculations of

hydrogenation of BN on metals have not been reported yet. Here, first-principles DFT calculations on Pd(111) and Pt(111) surfaces were first performed to elucidate the underlying mechanism

(Fig. 4 and Supplementary Figs. 14–18). In this work, we only considered the reaction pathways of BN hydrogenation to BA and the subsequent BA hydrogenolysis to TOL; while the condensation

reaction between BI and BA to DBI, as well as the following hydrogenation of DBI to DBA, were not calculated, because of the limitation of our computing resources for such large molecules

(Fig. 4a). On Pd(111), we found that the first hydrogenation of BN to the benzylideneimine (BI) intermediate, a key intermediate for DBA formation27, is thermoneutral with an effective

barrier of 1.32 eV. The following hydrogenation of BI to BA is slightly endothermic by 0.18 eV, but has a significantly lower effective barrier of 0.93 eV (Fig. 4b, and see Supplementary

Figs. 15 and 16 and Supplementary Note 3 for details). On Pt(111), the effective barriers of these two hydrogenation steps show an opposite trend to that on Pd(111): the second hydrogenation

step shows a considerably higher effective barrier (1.20 eV) than the first step (0.91 eV) (Fig. 4b, and see Supplementary Figs. 17 and 18 and Supplementary Note 4 for details). These two

consecutive hydrogenation steps are both exothermic by 0.44 and 0.49 eV, respectively. These results infer unambiguously that the considerably higher effective barrier for the second

hydrogenation step on Pt(111) favors extending the resident time of the BI surface intermediate, thereby prompting the condensation reaction via nucleophilic attack of BI surface

intermediate by BA to form the DBI intermediate (Fig. 4a)27,32. Subsequently, the DBI captures surface hydrogen atoms rapidly to produce the desired secondary amine (DBA) product on Pt

catalysts35. On the contrary, the largely decreased effective barrier for the second hydrogenation step on Pd(111) shortens the resident time of the BI intermediate, and drives the reaction

aggressively to the BA formation on Pd catalysts. These calculation results are in excellent consistence with our experimental results in Fig. 2a, b. Therefore, it is concluded that the

relative difference of effective energy barriers of first two hydrogenation steps govern the documented metal-dependent selectivity by regulating the resident time of the BI intermediate.

Further hydrogenolysis of BA to the undesired TOL by-product can certainly occur on both Pd(111) and Pt(111), since the corresponding barriers of 1.38 and 1.25 eV are only slightly higher

than the barriers of the two hydrogenation steps, which again consists excellently with the experimental results (Fig. 2a, b, f). To our best knowledge, this is the first theoretical view of

the metal-selectivity relations on Pd and Pt surfaces in hydrogenation of BN. In sharp contrast, on Pd1@Ni(111) SASA, where the isolated Pd atoms are within the outmost layer of Ni lattices

according to EXAFS analysis (Fig. 3a), the reaction profile changes dramatically (Fig. 4b and see Supplementary Figs. 19 and 20 and Supplementary Note 5 for detials): the hydrogenation of

BN to the BI intermediate becomes more facile on Pd1@Ni(111) (barrier 1.06 eV, exothermic 0.47 eV) than on Pd(111) (barrier 1.32 eV, exothermic 0 eV). On the contrary, the second

hydrogenation step becomes more difficult with a considerably higher effective barrier of 1.30 eV. According to the knowledge learned on Pd(111) and Pt(111), facilitation of the first

hydrogenation step but suppression of the second one would drastically improve the DBA formation, consistent with our experimental observation (Fig. 2c). Meanwhile, it is also found that the

BI intermediate adsorbs considerably stronger on Pd1@Ni(111) (2.74 eV) than on Pd(111) (2.59 eV) and Pt(111) (2.08 eV) (Supplementary Fig. 21). Such stronger adsorption would reduce the

mobility of BI on Pd1@Ni(111) and further accelerate the condensation reaction. These findings provide a molecular-level insight of breaking the metal-dependent selectivity in BN

hydrogenation over Pd1Ni SASA. Besides above, benefiting from the surrounding Ni (Supplementary Figs. 21–23 and Supplementary Note 6), hydrogenolysis of BA on Pd1@Ni(111) has a much higher

barrier of 1.56 eV than that on Pd(111) (1.38 eV) (Fig. 4b), again elucidating the effective inhibition of undesired hydrogenolysis of BA to TOL on 5Pd-Ni/SiO2 (Fig. 2c, f). The electronic

perturbation of Pd from the underlying Ni as suggested by XPS might play the important role (Fig. 3c). However, the DFT results seem not elucidate the activity enhancement on Pd1Ni SASA on

its own, since the highest effective energy barrier of BN hydrogenation to BA on Pd1@Ni(111) surface (1.30 eV) is very close to that on Pd(111) (1.32 eV) and Pt(111) surface (1.20 eV). In

fact, it is well-known that the hydrogenation activity not only depends on energetic profiles, but also correlates strongly with the competitive adsorption of substrate molecule and H216.

For bimetallic catalysts, hydrogen spillover could play very important roles for the activity enhancement39,72. For example, in hydrogenation of 3-nitrostyrene, Peng et al. reported that

Pt1Ni SAA catalyst had a TOF of ~1800 h−1, much higher than that of Pt single atoms supported on active carbon, TiO2, SiO2, and ZSM-5. The remarkable activity of Pt1/Ni nanocrystals was

attributed to sufficient hydrogen supply because of spontaneous dissociation of H2 on both Pt and Ni atoms as well as facile diffusion of H atoms on Pt1/Ni nanocrystals72. In our work, we

speculate that spontaneous dissociation of H2 on both Pd and Ni atoms provides a reservoir of active H atoms on Pd1Ni SASA surface, thus greatly accelerating the sequential hydrogenations.

SUBSTRATE EXPLORATION Finally, we further evaluated the 5Pd-Ni/SiO2 SASA sample in hydrogenation of a broad scope of nitrile substrates. As shown in Fig. 5, hydrogenation of aromatic

nitriles with either electron-donating groups (R = CH3, OCH3) or electron-withdrawing groups (R = F, CF3) and aliphatic nitriles, proceeded smoothly under mild conditions without any

additives and leading to excellent yield of the corresponding secondary amines above 94%. The major by-products were the corresponding primary amines, while the hydrogenolysis by-products

were completely inhibited in all cases, demonstrating the great potentials for industrial applications. In summary, we have demonstrated that isolating Pd with Ni breaks the strong

metal-selectivity relations in hydrogenation of nitriles, and prompts the yield of secondary amines drastically up to >94% over a broad scope of nitriles under middle conditions.

Meanwhile, the activity was also remarkably enhanced to about eight and four times higher than those of Pd and Pt catalysts, respectively. Importantly, the resulting materials also showed

excellent recyclability and a complete inhibition of the formation of hydrogenolysis by-product, demonstrating the great potentials for practical applications. DFT calculations, to our best

knowledge, provided the first theoretical view of the metal-selectivity relations on Pd and Pt surfaces, and unveiled the synergy in Pd1Ni SASA for the switch of reaction pathway from

primary amines on Pd to the exclusive formation of secondary amines. It should be noted that selective Pd ALD is essential to achieve the high DBA yield with complete TOL inhibition, while

such selective deposition might not be applicable to other supports such as Al2O3. Nonetheless, these findings open a promising avenue to rational design of metal catalyst with controlled

selectivity and activity. DATA AVAILABILITY The data underlying Figs. 1–5, Supplementary Figs. 2, 4–13, 16, 18, 20, and 23, DFT calculated XYZ coordination parameters of reactants,

intermediates, products, and transition states on Pd(111), Pt(111), and Pd1@Ni(111) surfaces are provided as a Source Data file. The other data that support the findings of this study are

available from the corresponding author upon request. REFERENCES * Petranyi, G., Ryder, N. S. & Stutz, A. Allylamine derivatives: new class of synthetic antifungal agents inhibiting

fungal squalene epoxidase. _Science_ 224, 1239–1241 (1984). Article ADS CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Nanavati, S. M. & Silverman, R. B. Mechanisms of inactivation of γ-aminobutyric

acid aminotransferase by the antiepilepsy drug γ-vinyl GABA (vigabatrin). _J. Am. Chem. Soc._ 113, 9341–9349 (1991). Article CAS Google Scholar * Salvatore, R. N., Yoon, C. H. & Jung,

K. W. Synthesis of secondary amines. _Tetrahedron_ 57, 7785–7811 (2001). Article CAS Google Scholar * Bagal, D. B. & Bhanage, B. M. Recent advances in transition metal-catalyzed

hydrogenation of nitriles. _Adv. Synth. Catal._ 357, 883–900 (2015). Article CAS Google Scholar * Werkmeister, S., Junge, K. & Beller, M. Catalytic hydrogenation of carboxylic acid

esters, amides, and nitriles with homogeneous catalysts. _Org. Process Res. Dev._ 18, 289–302 (2014). Article CAS Google Scholar * Muller, T. E. & Beller, M. Metal-initiated amination

of alkenes and alkynes. _Chem. Rev._ 98, 675–703 (1998). Article PubMed Google Scholar * Das, K. et al. Platinum-catalyzed direct amination of allylic alcohols with aqueous ammonia:

selective synthesis of primary allylamines. _Angew. Chem. Int. Ed._ 51, 150–154 (2012). Article CAS Google Scholar * Brown, B. R. _The Organic Chemistry Of Aliphatic Nitrogen Compounds_.

Vol. 28 (Oxford University Press, 1994). * Hartwig, J. F. Transition metal catalyzed synthesis of arylamines and aryl ethers from aryl halides and triflates: scope and mechanism. _Angew.

Chem. Int. Ed._ 37, 2046–2067 (1998). Article CAS Google Scholar * Hartwig, J. F. Evolution of a fourth generation catalyst for the amination and thioetherification of aryl halides. _Acc.

Chem. Res._ 41, 1534–1544 (2008). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Bissember, A. C., Lundgren, R. J., Creutz, S. E., Peters, J. C. & Fu, G. C.

Transition-metal-catalyzed alkylations of amines with alkyl halides: Photoinduced, copper-catalyzed couplings of carbazoles. _Angew. Chem. Int. Ed._ 52, 5129–5133 (2013). Article CAS

Google Scholar * Hahn, G., Kunnas, P., de Jonge, N. & Kempe, R. General synthesis of primary amines via reductive amination employing a reusable nickel catalyst. _Nat. Catal._ 2, 71–77

(2018). Article CAS Google Scholar * Murugesan, K., Beller, M. & Jagadeesh, R. V. Reusable nickel nanoparticles-catalyzed reductive amination for selective synthesis of primary

amines. _Angew. Chem. Int. Ed._ 58, 5064–5068 (2019). Article CAS Google Scholar * Bähn, S. et al. The catalytic amination of alcohols. _ChemCatChem_ 3, 1853–1864 (2011). Article CAS

Google Scholar * Zimmermann, B., Herwig, J. & Beller, M. The first efficient hydroaminomethylation with ammonia: with dual metal catalysts and two-phase catalysis to primary amines.

_Angew. Chem. Int. Ed._ 38, 2372–2375 (1999). Article CAS Google Scholar * Bakker, J. J. W., van der Neut, A. G., Kreutzer, M. T., Moulijn, J. A. & Kapteijn, F. Catalyst performance

changes induced by palladium phase transformation in the hydrogenation of benzonitrile. _J. Catal._ 274, 176–191 (2010). Article CAS Google Scholar * Chen, F. et al. Stable and inert

cobalt catalysts for highly selective and practical hydrogenation of C≡N and C═O bonds. _J. Am. Chem. Soc._ 138, 8781–8788 (2016). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * De Bellefon, C.

& Fouilloux, P. Homogeneous and heterogeneous hydrogenation of nitriles in a liquid phase: chemical, mechanistic, and catalytic aspects. _Catal. Rev._ 36, 459–506 (1994). Article Google

Scholar * Hegedűs, L. & Máthé, T. Selective heterogeneous catalytic hydrogenation of nitriles to primary amines in liquid phase: part I. Hydrogenation of benzonitrile over palladium.

_Appl. Catal. A_ 296, 209–215 (2005). Article CAS Google Scholar * McMillan, L. et al. The application of a supported palladium catalyst for the hydrogenation of aromatic nitriles. _J.

Mol. Catal. A Chem._ 411, 239–246 (2016). Article CAS Google Scholar * Lu, S. L., Wang, J. Q., Cao, X. Q., Li, X. M. & Gu, H. W. Selective synthesis of secondary amines from nitriles

using Pt nanowires as a catalyst. _Chem. Commun._ 50, 3512–3515 (2014). Article CAS Google Scholar * Greenfield, H. Hydrogenation of benzonitrile to dibenzylamine. _Ind. Eng. Chem. Prod.

Res. Dev._ 15, 156–158 (1976). Article CAS Google Scholar * Galan, A., De Mendoza, J., Prados, P., Rojo, J. & Echavarren, A. M. Synthesis of secondary amines by rhodium catalyzed

hydrogenation of nitriles. _J. Org. Chem._ 56, 452–454 (1991). Article CAS Google Scholar * Reguillo, R., Grellier, M., Vautravers, N., Vendier, L. & Sabo-Etienne, S.

Ruthenium-catalyzed hydrogenation of nitriles: insights into the mechanism. _J. Am. Chem. Soc._ 132, 7854–7855 (2010). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Bornschein, C. et al. Mild and

selective hydrogenation of aromatic and aliphatic (di)nitriles with a well-defined iron pincer complex. _Nat. Commun._ 5, 4111 (2014). Article ADS CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Elangovan,

S. et al. Selective catalytic hydrogenations of nitriles, ketones, and aldehydes by well-defined manganese pincer complexes. _J. Am. Chem. Soc._ 138, 8809–8814 (2016). Article CAS PubMed

Google Scholar * Braun, J. V., Blessing, G. & Zobel, F. Katalytische hydrierungen unter druck bei gegenwart von nickelsalzen, VI.: nitrile. _Ber. dtsch. Chem. Ges._ 56, 1988–2001

(1923). Article Google Scholar * Gomez, S., Peters, J. A. & Maschmeyer, T. The reductive amination of aldehydes and ketones and the hydrogenation of nitriles: mechanistic aspects and

selectivity control. _Adv. Synth. Catal._ 344, 1037–1057 (2002). Article CAS Google Scholar * McMichael, A. Carcinogenicity of benzene, toluene and xylene: epidemiological and

experimental evidence. _IARC Sci. Publ_. 85, 3–18 (1988). * Cheng, H. et al. Selective hydrogenation of benzonitrile in multiphase reaction systems including compressed carbon dioxide over

Ni/Al2O3 catalyst. _J. Mol. Catal. A Chem._ 379, 72–79 (2013). Article CAS Google Scholar * Dai, C. et al. Efficient and selective hydrogenation of benzonitrile to benzylamine:

improvement on catalytic performance and stability in a trickle-bed reactor. _New J. Chem._ 41, 3758–3765 (2017). Article CAS Google Scholar * López-De Jesús, Y. M., Johnson, C. E.,

Monnier, J. R. & Williams, C. T. Selective hydrogenation of benzonitrile by alumina-supported Ir–Pd catalysts. _Top. Catal._ 53, 1132–1137 (2010). Article CAS Google Scholar *

Hartung, W. H. Catalytic reduction of nitriles and oximes. _J. Am. Chem. Soc._ 50, 3370–3374 (1928). Article CAS Google Scholar * Chatterjee, M. et al. Hydrogenation of nitrile in

supercritical carbon dioxide: a tunable approach to amine selectivity. _Green. Chem._ 12, 87–93 (2010). Article CAS Google Scholar * Liu, L. et al. Pd-CuFe catalyst for transfer

hydrogenation of nitriles: controllable selectivity to primary amines and secondary amines. _iScience_ 8, 61–73 (2018). Article ADS CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Liu, L.

et al. A ppm level Rh-based composite as an ecofriendly catalyst for transfer hydrogenation of nitriles: triple guarantee of selectivity for primary amines. _Green Chem._ 21, 1390–1395

(2019). Article CAS Google Scholar * Li, J. et al. Moderate activity from trace palladium alloyed with copper for the chemoselective hydrogenation of –CN and –NO2 with HCOOH.

_ChemistrySelect_ 4, 7346–7350 (2019). Article CAS Google Scholar * Shao, Z., Fu, S., Wei, M., Zhou, S. & Liu, Q. Mild and selective cobalt-catalyzed chemodivergent transfer

hydrogenation of nitriles. _Angew. Chem. Int. Ed._ 55, 14653–14657 (2016). Article CAS Google Scholar * Kyriakou, G. et al. Isolated metal atom geometries as a strategy for selective

heterogeneous hydrogenations. _Science_ 335, 1209–1212 (2012). Article ADS CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Lucci, F. R. et al. Selective hydrogenation of 1,3-butadiene on platinum–copper

alloys at the single-atom limit. _Nat. Commun._ 6, 8550 (2015). Article ADS PubMed CAS Google Scholar * Pei, G. X. et al. Ag alloyed Pd single-atom catalysts for efficient selective

hydrogenation of acetylene to ethylene in excess ethylene. _ACS Catal._ 5, 3717–3725 (2015). Article CAS Google Scholar * Sun, G. et al. Breaking the scaling relationship via thermally

stable Pt/Cu single atom alloys for catalytic dehydrogenation. _Nat. Commun._ 9, 4454 (2018). Article ADS PubMed PubMed Central CAS Google Scholar * Ge, J. et al. Atomically dispersed

Ru on ultrathin Pd nanoribbons. _J. Am. Chem. Soc._ 138, 13850–13853 (2016). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Feng, Q. et al. Isolated single-atom Pd sites in intermetallic

nanostructures: high catalytic selectivity for semihydrogenation of alkynes. _J. Am. Chem. Soc._ 139, 7294–7301 (2017). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Marcinkowski, M. D. et al.

Pt/Cu single-atom alloys as coke-resistant catalysts for efficient C–H activation. _Nat. Chem._ 10, 325–332 (2018). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Maeda, K. et al. Dibenzylamine

compounds and pharmaceutical use thereof. US Patent 7,807,701 B2 (2010). * Buckwalter, F. H. Dibenzylamine salts of penicillin. US Patent 2,585,432 A (1952). * Burattin, P., Che, M. &

Louis, C. Metal particle size in Ni/SiO2 materials prepared by deposition−precipitation: Influence of the nature of the Ni(II) phase and of its interaction with the support. _J. Phys. Chem.

B_ 103, 6171–6178 (1999). Article CAS Google Scholar * Lu, J. L. et al. Toward atomically-precise synthesis of supported bimetallic nanoparticles using atomic layer deposition. _Nat.

Commun._ 5, 3264 (2014). Article ADS PubMed CAS Google Scholar * Wang, H. W., Wang, C. L., Yan, H., Yi, H. & Lu, J. L. Precisely-controlled synthesis of Au@Pd core-shell bimetallic

catalyst via atomic layer deposition for selective oxidation of benzyl alcohol. _J. Catal._ 324, 59–68 (2015). Article CAS Google Scholar * Cao, L. et al. Atomically dispersed iron

hydroxide anchored on Pt for preferential oxidation of CO in H2. _Nature_ 565, 631–635 (2019). Article ADS CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Chen, X. et al. Solvent-driven selectivity control

to either anilines or dicyclohexylamines in hydrogenation of nitroarenes over a bifunctional Pd/MIL-101 catalyst. _ACS Catal._ 8, 10641–10648 (2018). Article CAS Google Scholar * Hou, R.

J., Porosoff, M. D., Chen, J. G. & Wang, T. F. Effect of oxide supports on Pd-Ni bimetallic catalysts for 1,3-butadiene hydrogenation. _Appl. Catal. A_ 490, 17–23 (2015). Article CAS

Google Scholar * Nurunnabi, M. et al. Oxidative steam reforming of methane under atmospheric and pressurized conditions over Pd/NiO–MgO solid solution catalysts. _Appl. Catal. A_ 308, 1–12

(2006). Article CAS Google Scholar * Aich, P. et al. Single-atom alloy Pd–Ag catalyst for selective hydrogenation of acrolein. _J. Phys. Chem. C_ 119, 18140–18148 (2015). Article CAS

Google Scholar * Mori, K., Hara, T., Mizugaki, T., Ebitani, K. & Kaneda, K. Hydroxyapatite-supported palladium nanoclusters: a highly active heterogeneous catalyst for selective

oxidation of alcohols by use of molecular oxygen. _J. Am. Chem. Soc._ 126, 10657–10666 (2004). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Pei, G. X. et al. Performance of Cu-alloyed Pd

single-atom catalyst for semihydrogenation of acetylene under simulated front-end conditions. _ACS Catal._ 7, 1491–1500 (2017). Article CAS Google Scholar * Lear, T. et al. The

application of infrared spectroscopy to probe the surface morphology of alumina-supported palladium catalysts. _J. Chem. Phys._ 123, 174706 (2005). Article ADS PubMed CAS Google Scholar

* Yudanov, I. V. et al. CO adsorption on Pd nanoparticles: Density functional and vibrational spectroscopy studies. _J. Phys. Chem. B_ 107, 255–264 (2003). Article CAS Google Scholar *

Zhang, L. et al. Efficient and durable Au alloyed Pd single-atom catalyst for the Ullmann reaction of aryl chlorides in water. _ACS Catal._ 4, 1546–1553 (2014). Article CAS Google Scholar

* Lu, J. et al. Coking- and sintering-resistant palladium catalysts achieved through atomic layer deposition. _Science_ 335, 1205–1208 (2012). Article ADS CAS PubMed Google Scholar *

Xin, P. et al. Revealing the active species for aerobic alcohol oxidation by using uniform supported palladium catalysts. _Angew. Chem. Int. Ed._ 57, 4642–4646 (2018). Article CAS Google

Scholar * Wei, X. et al. Bimetallic Au–Pd alloy catalysts for N2O decomposition: Effects of surface structures on catalytic activity. _J. Phys. Chem. C_ 116, 6222–6232 (2012). Article CAS

Google Scholar * Bertolini, J. C., Miegge, P., Hermann, P., Rousset, J. L. & Tardy, B. On the reactivity of 2d Pd surface alloys obtained by surface segregation or deposition

technique. _Surf. Sci._ 331, 651–658 (1995). Article ADS Google Scholar * Hermann, P., Simon, D. & Bigot, B. Pd deposits on Ni(111): a theoretical study. _Surf. Sci._ 350, 301–314

(1996). Article ADS CAS Google Scholar * Hermann, P. et al. The Pd/Ni (110) bimetallic system: Surface characterisation by LEED, AES, XPS, and LEIS techniques; new insight on catalytic

properties. _J. Catal._ 163, 169–175 (1996). Article CAS Google Scholar * Nutt, M. O., Heck, K. N., Alvarez, P. & Wong, M. S. Improved Pd-on-Au bimetallic nanoparticle catalysts for

aqueous-phase trichloroethene hydrodechlorination. _Appl. Catal. B_ 69, 115–125 (2006). Article CAS Google Scholar * Carlsson, A. F., Naschitzki, M., Bäumer, M. & Freund, H.-J. The

structure and reactivity of Al2O3-supported cobalt− palladium particles: A CO-TPD, STM, and XPS study. _J. Phys. Chem. B_ 107, 778–785 (2003). Article CAS Google Scholar * Lozano-Blanco,

G. & Adamczyk, A. J. Cobalt-catalyzed nitrile hydrogenation: Insights into the reaction mechanism and product selectivity from DFT analysis. _Surf. Sci._ 688, 31–44 (2019). Article ADS

CAS Google Scholar * Adamczyk, A. J. First-principles analysis of acetonitrile reaction pathways to primary, secondary, and tertiary amines on Pd (111). _Surf. Sci._ 682, 84–98 (2019).

Article ADS CAS Google Scholar * Lozano-Blanco, G., Tatarchuk, B. J. & Adamczyk, A. J. Building a microkinetic model from first principles for higher amine synthesis on Pd catalyst.

_Ind. Eng. Chem. Res._ https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.iecr.9b03577 (2019). Article Google Scholar * Peng, Y. et al. Pt single atoms embedded in the surface of Ni nanocrystals as highly active

catalysts for selective hydrogenation of nitro compounds. _Nano Lett._ 18, 3785–3791 (2018). Article ADS CAS PubMed Google Scholar Download references ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This work was

supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grants 21673215, 21688102, and 21703222), the National Key Research & Development Program of China (Grant 2016YFA02006),

the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (WK2060030029), Users with Excellence Program of Hefei Science Center CAS (2019HSC-UE016), and the Max-Planck Partner Group. The

calculations were performed on the supercomputing system in the Supercomputing Center of University of Science and Technology of China and the High-performance Computing Platform of Anhui

University. The authors also gratefully thank the BL14W1 beamline at the Shanghai Synchrotron Radiation Facility (SSRF), the BL10B beamline at National Synchrotron Radiation Laboratory

(NSRL), China. AUTHOR INFORMATION Author notes * These authors contributed equally: Hengwei Wang, Qiquan Luo. AUTHORS AND AFFILIATIONS * Hefei National Laboratory for Physical Sciences at

the Microscale, University of Science and Technology of China, Hefei, 230026, P. R. China Hengwei Wang, Qiquan Luo, Yue Lin, Qiaoqiao Guan, Jinlong Yang & Junling Lu * Department of

Chemical Physics, Key Laboratory of Surface and Interface Chemistry and Energy Catalysis of Anhui Higher Education Institutes, iChem, University of Science and Technology of China, Hefei,

230026, P. R. China Hengwei Wang, Qiaoqiao Guan, Jinlong Yang & Junling Lu * National Synchrotron Radiation Laboratory, University of Science and Technology of China, Hefei, 230029, P.

R. China Wei Liu, Xusheng Zheng, Haibin Pan, Junfa Zhu, Zhihu Sun & Shiqiang Wei Authors * Hengwei Wang View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google

Scholar * Qiquan Luo View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Wei Liu View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed

Google Scholar * Yue Lin View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Qiaoqiao Guan View author publications You can also search for this author

inPubMed Google Scholar * Xusheng Zheng View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Haibin Pan View author publications You can also search for

this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Junfa Zhu View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Zhihu Sun View author publications You can also search

for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Shiqiang Wei View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Jinlong Yang View author publications You can

also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Junling Lu View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar CONTRIBUTIONS J.L. designed the

experiments; H.W. synthesized and characterized the catalysts and performed the catalytic performance evaluation; H.W., S.W., W.L., and Z.S. performed the XAFS measurements; H.W. X.Z., H.P.,

and J.Z. did the XPS characterization; Y.L. did the STEM measurements; Q.G. helped catalyst synthesis; Q.L. and J.Y. did the DFT calculations; J.L. and H.W. co-wrote the manuscript, and all

the authors contributed to the overall scientific interpretation and edited the manuscript. CORRESPONDING AUTHOR Correspondence to Junling Lu. ETHICS DECLARATIONS COMPETING INTERESTS The

authors declare no competing interests. ADDITIONAL INFORMATION PEER REVIEW INFORMATION _Nature Communications_ thanks Andrew Adamczyk, Hongbin Sun and other, anonymous, reviewers for their

contributions to the peer review of this work. Peer review reports are available. PUBLISHER’S NOTE Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and

institutional affiliations. SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION SUPPLEMENTARY INFO PEER REVIEW FILE RIGHTS AND PERMISSIONS OPEN ACCESS This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0

International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and

the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative

Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by

statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. Reprints and permissions ABOUT THIS ARTICLE CITE THIS ARTICLE Wang, H., Luo, Q., Liu, W. _et al._ Quasi Pd1Ni single-atom surface alloy catalyst

enables hydrogenation of nitriles to secondary amines. _Nat Commun_ 10, 4998 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-019-12993-x Download citation * Received: 28 June 2019 * Accepted: 09

October 2019 * Published: 01 November 2019 * DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-019-12993-x SHARE THIS ARTICLE Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Get shareable link Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article. Copy to clipboard Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative