Fluorinated hybrid solid-electrolyte-interphase for dendrite-free lithium deposition

- Select a language for the TTS:

- UK English Female

- UK English Male

- US English Female

- US English Male

- Australian Female

- Australian Male

- Language selected: (auto detect) - EN

Play all audios:

ABSTRACT Lithium metal anodes have attracted extensive attention owing to their high theoretical specific capacity. However, the notorious reactivity of lithium prevents their practical

applications, as evidenced by the undesired lithium dendrite growth and unstable solid electrolyte interphase formation. Here, we develop a facile, cost-effective and one-step approach to

create an artificial lithium metal/electrolyte interphase by treating the lithium anode with a tin-containing electrolyte. As a result, an artificial solid electrolyte interphase composed of

lithium fluoride, tin, and the tin-lithium alloy is formed, which not only ensures fast lithium-ion diffusion and suppresses lithium dendrite growth but also brings a synergistic effect of

storing lithium via a reversible tin-lithium alloy formation and enabling lithium plating underneath it. With such an artificial solid electrolyte interphase, lithium symmetrical cells show

outstanding plating/stripping cycles, and the full cell exhibits remarkably better cycling stability and capacity retention as well as capacity utilization at high rates compared to bare

lithium. SIMILAR CONTENT BEING VIEWED BY OTHERS LI2ZRF6-BASED ELECTROLYTES FOR DURABLE LITHIUM METAL BATTERIES Article 08 January 2025 DUAL FLUORINATION OF POLYMER ELECTROLYTE AND

CONVERSION-TYPE CATHODE FOR HIGH-CAPACITY ALL-SOLID-STATE LITHIUM METAL BATTERIES Article Open access 23 December 2022 SUPPRESSING ELECTROLYTE-LITHIUM METAL REACTIVITY VIA LI+-DESOLVATION IN

UNIFORM NANO-POROUS SEPARATOR Article Open access 10 January 2022 INTRODUCTION Next-generation batteries based on lithium (Li) metal anodes, such as Li-air and Li-sulfur have been

extensively studied owing to the high theoretical capacity (3860 mAh g−1, low density (0.59 g cm−3), and low redox potential (−3.04 V versus standard hydrogen potential) of Li1. Li batteries

need to possess a higher capacity in order to integrate with renewable energy sources2,3,4. However, nonuniform Li plating, the infinite volume change of Li during plating/stripping, and

the formation of fragile solid-electrolyte-interphase (SEI) lead to the growth of Li dendrites and formation of “dead Li”. Such irreversibility consumes both Li and electrolyte, leading to

sustained capacity fading and low coulombic efficiency (CE)5. Li dendrites and “dead Li” also cause severe safety concerns of any batteries based on Li metal anode6. Substantial efforts have

been done to deposit Li metal in a dense and reversible manner. For example, conventional copper foils have been replaced by advanced current collectors with nanostructured morphology to

lower the current density and manipulate Li deposition sites7. Modifications of the separator have also been performed8,9. The use of solid or gel electrolytes also promises various

advantages over volatile and flammable organic liquid electrolytes in their potentials to prevent parasitic reactions with Li, while providing excellent flexibility10,11,12. Engineering ex

situ protective layers have attracted much attention for Li metal batteries (LMBs). Improving the modulus properties and ionic conductivity of the interphase by various strategies have been

reported13,14. The poor Li contact between these interfacial layers and bulk Li could lead to an increase in both interfacial and overall cell resistance. The low wettability of interphase

towards nonaqueous electrolyte also leads to sluggish Li-ion transport. Differing from surface engineering of the artificial interphase layer, the use of various electrolyte additives7,15

provides an alternative pathway, where a more intimate contact could be ensured. Recently, fluorinating SEI with LiF as a key component has been widely adopted to improve the cycling

performance of Li metal anode based on two hypotheses: (1) LiF is an excellent electronic insulator whose wide gap effectively prevents electron tunneling16; (2) When interfacing with other

ingredients at nanoscale, LiF could provide a high ionic conductivity, low diffusing energy, and high surface energy, which not only allows sufficiently fast Li-ion kinetics but more

importantly promotes the electrodeposition of Li in a parallel rather than vertical manner17,18. Consequently, LiF-based interphase ensures better surface morphology and serves as a robust

barrier to Li dendrite growth17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24. Besides LiF, Li-based alloys have also been studied as protective interphase to suppress Li dendritic growth, because Sn–Li alloy phase

could reduce the Li-ion diffusion barrier, and lead to improved Li metal interphase stability25,26,27. Such alloy approaches include the in situ formation of Sn–Li, Li13–In3, Li–Zn, Li3–Bi,

Li3–As, Au–Li, Si–Li, etc25,28. However, the development of an artificial SEI is still at its early stages. The mechanical and electrochemical instability of interphase leads to persistent

deterioration. Low Li-ion conductivity, chemical instability, morphological inhomogeneity, and the subsequent uneven growth of natural SEI remain to be unresolved. In particular, there has

never been synergy established between inert but protective LiF, the electrochemically active Sn and Sn–Li alloy on the SEI. With these considerations in mind, we report a one-step approach

to create an artificial SEI composed of LiF, Sn, and Sn–Li alloy tightly anchored to the Li surface. The artificially generated hybrid SEI not only eliminates Li dendrite and dead Li, but

simultaneously stores Li via the formation of an alloy and enables Li plating underneath it. The hybrid SEI-modified Li symmetrical cells show outstanding plating/stripping cycles (~2325 h)

with reduced overpotential compared to the bare Li. When coupled with a high-loading (11.88 mg cm−2) LiNi1/3Co1/3Mn1/3O2 cathode, Li full cells exhibit remarkably higher performance than

bare Li anode in cycling stability, capacity retention, and capacity utilization at higher rates. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first demonstration of hybrid SEI that provides

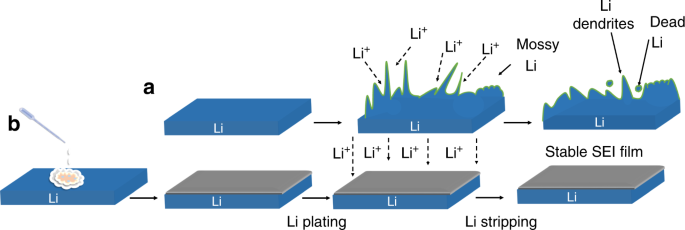

new solutions to the challenges in Li metal anodes. RESULTS PREPARATION OF AN ARTIFICIAL FLUORINATED HYBRID SEI Figure 1a shows the growth of Li dendrites and “dead Li” on the bare Li metal

after plating and stripping cycles. Figure 1b exhibits the fabrication process of fluorinated hybrid SEI by treating Li with SnF2 to obtain dendrite-free Li plating/stripping. By casting an

electrolyte containing SnF2 on the surface of the Li metal electrode, a replacement reaction between Li metal and SnF2, and an alloying reaction between Li metal and Sn occur as

follows20,25. $${\mathrm{SnF}}_2 + 2{\mathrm{Li}} \to 2{\mathrm{LiF}} + {\mathrm{Sn}}$$ (1) $$5{\mathrm{Li}} + 2{\mathrm{Sn}} \leftrightarrow {\mathrm{Li}}_5{\mathrm{Sn}}_2$$ (2)

Electrolytes with different concentrations of SnF2 (1 wt%, 3 wt%, and 5 wt%) were cast on bare Li electrodes. X-ray diffraction (XRD) measurements were performed to characterize the phase

change of Li and investigate the components of the artificial SEI layer. To avoid the direct contact of the electrode with air or moisture, all the samples were measured under the protection

of Kapton tape that has a wide diffraction peak at ~20°. Figure 2a shows the XRD spectra of artificial SEI layers generated on the Li electrode by treating with electrolytes containing 1,

3, and 5 wt% of SnF2. The pure Li metal shows the XRD peaks at ~36°, 52°, and 65° as shown in Supplementary Fig. 1. The artificial SEI layer constitutes a beneficial Sn–Li alloy (Li5Sn2),

LiF, and Sn. Peaks at ~31.1°, 32.4°, and 44.1° correspond to Sn. Peaks at ~23.4°, 27.5°, 40.5° correspond to Li5Sn2. Peaks at ~38.7°, 44.9°, and 65.4° correspond to LiF24,25,29. With

increasing concentration of SnF2, the peak strength of LiF and Li5Sn2 increases, and a new peak at ~23° appears that corresponds to Li5Sn225,30. As the artificial fluorinated hybrid SEI

formed on top of Li has a thickness of 10 µm or higher, this might be the reason for the minimal Li peak at 65°. As Li5Sn2, Sn, and LiF are on top of the Li electrode, this is why their

peaks are pretty strong. The silver shiny surface of bare Li metal (Fig. 2b) appears dark grey, immediately after treatment and turns to whitish when fully dried (Fig. 2c–e). Figure 2c shows

that with 1 wt% SnF2, the artificial SEI does not completely cover or protect the Li surface. With 3 and 5 wt% SnF2 treatment (Fig. 2d, e), full coverage of the artificial SEI layer can be

observed. The scanning electron microscope (SEM) image of the bare Li (0 wt% SnF2, Fig. 2f) shows a rough surface. Figure 2g–i shows the topography SEM image of the artificial SEI layers

obtained using an electrolyte containing 1, 3, and 5 wt% SnF2, respectively. The SEI layer with 1 wt% SnF2 has pinholes (Fig. 2g) on the surface that allow penetration of electrolyte,

resulting in the side reactions with the Li underneath. As a result, the electrolyte and Li are consumed that leads to low CE and capacity decay31. As a comparison, SEM images of the

artificial SEI layers with 3 and 5 wt% SnF2 (Fig. 2h, i) do not show any pinholes or cracks that avoids direct contact of electrolyte with the Li underneath. The cross-sectional SEM image

(Fig. 2j–m) shows that the average thickness (t) of the artificial SEI treated with an electrolyte containing 1, 3, and 5 wt% SnF2 is 10 µm, 25 µm, and 55 µm, respectively. The thicker SEI

has a higher Li-ion barrier energy or higher impedance resulting in slow Li-ion diffusion32. Thus, the SEI layer thickness should be optimized in order to protect Li physically to avoid

direct contact with the electrolyte. This will lead to high Li-ion conductivity. The Li protected by an artificial fluorinated hybrid SEI with a thickness of 10 µm, 25 µm, and 55 µm is

abbreviated as AFH-10, AFH-25, and AFH-55, respectively. LI PLATING/STRIPPING PERFORMANCE AND IMPEDANCE MEASUREMENT OF SYMMETRIC CELLS Li plating/stripping tests were carried out to

characterize the SEI layers. Figure 3a shows the comparison of the voltage–time profile of Li symmetric cells with different thicknesses of an artificial SEI generated by treating Li with

SnF2 and bare Li. Voltage profiles show that the best Li deposition behavior and longest plating/stripping cycles were achieved by AFH-25. The AFH-25 fully protects the Li electrode as well

as renders a uniform, smooth, and dendrite-free Li deposition compared to AFH-10, and AFH-55 (Supplementary Fig. 2a–c). Further, to find the best SEI layer for the Li metal electrode

protection, various characterizations have been conducted on the SEI layers from different SnF2 concentrations. The impedance measurements were carried out to calculate the charge transfer

resistance (_R_ct) of symmetrical cells. Figure 3b shows the Nyquist plot of bare Li and, AFH-10, AFH-25, and AFH-55, respectively. The impedance results were fitted using an equivalent

circuit as shown in Supplementary Fig. 2d, e. The bare Li anode has no artificial SEI before Li plating/stripping cycling. Although there is in situ SEI formation when the bare Li contacts

the electrolyte before Li plating/stripping cycling, such SEI is very thin and does not fully cover the surface of the Li electrode. This SEI acts as an insignificant interfacial resistance

layer19; therefore, the bare Li symmetrical cell before Li plating/stripping cycling just has one Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy (EIS) semicircle (Fig. 3b). The single semicircle

indicates the _R_ct between the bare Li electrode and electrolyte33. However, after Li plating/stripping cycles, a much thicker SEI (Supplementary Fig. 10a) is formed and fully covers the

bare Li. This supports the presence of two semicircles (Fig. 3c, d) in bare Li after 10 cycles and 50 cycles. The slightly higher _R_s of SnF2–Li symmetrical cell compared to bare Li

symmetrical cell at fresh conditions can be attributed to an artificial SEI film of SnF2-treated Li34. The higher _R_ct in bare Li symmetrical cell before plating stripping cycles can be

attributed to the lower electrolyte wettability of the Li electrode that leads to sluggish Li-ion transport19,35. In addition, the absence of a protective layer to inhibit the possible side

reactions leads to electrolyte consumption, and the formation of unstable and fragile SEI19,25,35. Thus, the cell’s impedance increases. In contrast, AFH-10, AFH-25, and AFH-55 symmetrical

cells show two semicircles. The first semicircle in the higher frequency range indicates the interfacial resistance of the artificial SEI or resistance of Li-ion flux through an artificial

SEI, and the second semicircle in the lower frequency range indicates the _R_ct between the artificial SEI and the electrolyte19,33,36,37,38,39. The lower _R_ct of AFH-10, AFH-25, and AFH-55

symmetrical cells can be attributed to the better electrolyte wettability of the artificial SEI, the effective control of side reactions, and the stabilized SEI35,40,41. In addition, the

LiF in the SEI layer has high Li-ion conductivity, low diffusion barrier, and high surface energy. These allow sufficient Li-ion transport that lowers the _R_ct17,18,40,41. The symmetrical

cells based on the AFH-25 anode exhibit the least _R_ct value of 47 Ω, which can be attributed to the fast Li-ion transport with an optimized SEI thickness of 25 µm. All the quantified

impedance results are summarized in Supplementary Table 1. Thus, 25 µm is considered as the optimal thickness of SEI. Further measurements, characterizations, and comparisons were based on

the bare Li and AFH-25 unless stated. The stability of usual SEI in bare Li and AFH-25 in protected Li was measured using a Nyquist plot as a function of time (Supplementary Fig. 2f, g) and

impedance results are listed in Supplementary Table 2. In bare Li, the _R_ct of the symmetrical cell increases continuously from 343.50 Ω at fresh conditions to 1717.00 Ω at 600 h (hours).

In contrast, the AFH-25 symmetrical cell shows a gradual increment in _R_ct and remains steady, i.e., 47.00 Ω at the fresh condition and remains steady around 75.75 Ω at 600 h. To

investigate the stability of the SEI, impedance measurements of bare Li and AFH-25 were carried out after 10 cycles and 50 cycles of plating/stripping as shown in Fig. 3c, d. The _R_s of

bare Li increases from 2.39 Ω at the fresh condition to ~28 Ω after 10 cycles, and ~ 33 Ω after 50 cycles. The _R_s of AFH-25 increases from 9.59 Ω at fresh to ~18 Ω after 10 cycles, and ~22

Ω after 50 cycles. The higher value of _R_s in the bare Li compared to AFH-25 indicates a higher amount of electrolyte consumption in bare Li due to the formation of Li dendrites with a

high surface area, formation/deformation of SEI42, and other inactive products formed from side reactions43. After 10 cycles of plating/stripping, the _R_ct of bare Li and AFH-25 were ~88.43

Ω and ~48.04 Ω, respectively. After 50 cycles of plating/stripping cycles, _R_ct of bare Li and AFH-25 reduced to ~74.61 Ω and ~37.62 Ω, respectively. The decrease in _R_ct of bare Li after

10 cycles and 50 cycles can be attributed to the higher surface area of Li dendrite that allows more electrolyte contact, and dissolution of the passivation film44. However, the excessive

consumption of electrolytes ultimately leads to electrolyte dry out causing premature cell failure32. In contrast, the decrease in _R_ct after the 10 cycles and 50 cycles in AFH-25 can be

attributed to the stabilization of artificial SEI. The AFH-25 provides higher electrolyte wettability, higher Li-ion conductivity, lower diffusion barrier, and higher surface energy. These

allow sufficient Li-ion transport that lowers the _R_ct17,18. In addition, the AFH-25 prevents the direct contact of electrolyte and Li electrode to inhibit the reaction between Li and

electrolyte. Moreover, the Sn–Li alloy is responsible to lower the Li-ion diffusion barrier for improving the Li metal interphase stability25,26,27,45,46,47. Further, the Li-ion transference

number (TLi+) in the absence of an artificial layer was calculated to be 0.43 and with AFH-25, the value of TLi+ increased to 0.52 (calculated from Supplementary Fig. 3). The increase in

TLi+ can be attributed to the increase in Li+ fraction by the dissociation of ion pairs48. This demonstrates that the artificial SEI facilitates fast movement of Li-ion and is beneficial for

enhanced cycling performance22,24. MATERIALS CHARACTERIZATIONS X-ray photoelectron spectrum (XPS) measurement was employed to investigate the chemical composition on the SEI surface of

AFH-25 anode. Supplementary Fig. 4a shows two main peaks at 487.70 eV and 496.01 eV that can be assigned to Sn 2d5/2 and Sn 3d5/2, respectively, indicating the presence of Sn in an

artificial SEI25,49. Sn as an SEI constituent stores Li by alloying reaction to form Li5Sn225,50. The single Li 1 s peak at 55.79 eV (Supplementary Fig. 4b) and the single F 1 s peak at

684.96 eV (Supplementary Fig. 4c) correspond to the presence of LiF18,20. The LiF as a component of SEI regulates uniform Li plating/stripping20,21,51. Atomic force microscopy (AFM) was

performed to observe surface topography and measure the corresponding Young’s modulus of bare Li and AFH-25 as shown in Supplementary Fig. 5a–d. The average root mean square (r.m.s.)

roughness value of bare Li and AFH-55 was 260 nm and 38 nm, respectively. Higher roughness indicates the uneven surfaces that can create large protuberance responsible for uneven Li

deposition52. In contrast, the smooth surface of protected Li renders homogenous Li deposition. The corresponding Young’s modulus mapping of bare Li and AFH-25 shows an average Young’s

modulus value of 0.28 GPa and 55.60 GPa, respectively. This high value of Young’s modulus can be attributed to the contribution of all SEI components (LiF, Sn–Li, and Sn). Due to the strong

ionic bond between Li and F, LiF shows Young’s modulus value ranging from 50 to 140 GPa53,54,55. The B1 crystal structure of LiF (similar to NaCl type) remains invariant under high pressure

up to ~100 GPa and high temperature up to the melting point56. In addition, Sn is considered as a mechanically robust and highly stable material57,58. Based on the crystal orientation, the

theoretical range for Young’s modulus of Sn varies from 26.30 to 84.70 GPa57,59,60,61 and that of Li5Sn2 is from 40.96 to 74.20 GPa57,62. To better understand the mechanism of the superior

performance of fluorinated artificial SEI layers, contact angle and transference number measurements were conducted. The contact angle measurement was found to be 30° for bare Li and 1° for

AFH-25 as shown in Supplementary Fig. 6a, b. This higher electrolyte affinity leads to a higher surface energy of the SEI layer that facilitates fast Li-ion diffusion and nucleation. In

addition, linear sweep voltammetry shows that the bare Li has a steeper slope than the AFH-25 (Supplementary Fig. 6c). This implies that the artificial SEI protective layer of Li lowers the

electronic conductivity. The electronic resistive nature of SEI is favorable to first deposit/plate Li underneath the SEI. Thus, even with a high current density and large deposition amount

of Li, we can still lower the local current density in order to homogenize the Li-ion distribution in the SEI layer. The growth of Li dendrite is also inhibited due to the semiconducting

nature of SEI32. In this work, the ionic conductivity of the protected Li was calculated to be 5.84 × 10−4 S cm−1 (Supplementary Fig. 6d). This value of ionic conductivity is large enough to

diffuse Li-ion37. ELECTROCHEMICAL PERFORMANCE, ELEMENTAL COMPOSITION, AND LI DEPOSITION MORPHOLOGY To understand the electrochemical properties of the SEI, cyclic voltammetry (CV)

measurements of bare Li, and AFH-25 symmetrical cells were investigated (Fig. 4a, b). The bare Li symmetrical cell showed almost a straight line indicating the Li plating/stripping. In

contrast, the AFH-25 symmetrical cell showed broad peaks at ~0.12 V and at ~−0.12 V over multiple cycles in addition to the typical Li/Li+ polarization curves, confirming the occurrence of

lithiation/delithiation of Tin (Sn) and Li plating/stripping underneath the SEI. This indicates that the electrochemically active Sn can reversibly store Li by the formation of Sn–Li

alloy25. A similar observation of sodiation/desodiation of Sn was reported in Na-metal battery, suggesting the favorable reaction mechanism of the Sn-based SEI45. To observe the distribution

of elements present on the surface of AFH-25, the energy dispersive spectrum (EDS) elemental mapping was carried out. The zoom-in SEM image and its corresponding EDS elemental mapping are

shown in Fig. 4c–e. The zoom-in SEM image (Fig. 4c) shows that the artificial fluorinated hybrid SEI is composed of compactly stacked microstructures20. The inset image of EDS (Fig. 4d) is

the combined elemental mapping. The elemental mapping of surface morphology (Fig. 4e) shows that the elements C, O, F, and Sn are uniformly distributed. The EDS elemental mapping (Fig. 4e)

shows that F and Sn are uniformly distributed on the SEI. Thus, the compact surface morphology (Fig. 4c) of LiF, Sn–Li alloy and Sn contribute to the total surface strength. This Young’s

modulus value is significantly high to suppress the Li dendrite growth63, which indicates the artificial layer composed of Sn, LiF, and Sn–Li alloy can withstand physical changes, provide

sufficient mechanical stability during Li plating /stripping, and offer high resistance/strength to suppress Li dendrite growth20,31,37,63,64,65,66,67,68,69. The plating/stripping voltage

profile of bare Li and AFH-25 was carried out to investigate interfacial stability. Figure 5a, b shows the voltage profile of Li plating/stripping of bare Li and AFH-25 symmetrical cells

that achieved a capacity of 1 mAh cm−2 at a current density of 0.5 mA cm−2 and 1 mA cm−2, respectively. The AFH-25 symmetrical cells show a longer plating/stripping cycles than the bare Li.

In bare Li, the overpotential increases continuously that leads to the early death of cell at ~400 h and ~250 h at 0.5 mA cm−2 and 1 mA cm−2, respectively. In contrast, AFH-25 symmetrical

cells show a stable voltage profile for longer plating/stripping cycles. The AFH-25 symmetrical cell can run up to ~2325 h and ~850 h of plating/stripping at 0.5 mA cm−2 and 1 mA cm−2,

respectively. In bare Li, the reaction between the electrolyte and Li electrode, growth of Li dendrite due to nonuniform Li deposition after plating/stripping, and formation of

fragile/unstable SEI can lead to electrolyte dry out32. Eventually, the overpotential occurs and causes the premature death of the cell. In contrast, the artificial SEI, formed by treating

with SnF2, physically protects the Li from side reactions with the electrolyte and provides a route for uniform Li deposition65. In addition, the SEI component such as Sn can reversibly

store Li by alloying. The presence of LiF in the protective SEI layer facilitates uniform Li diffusion to reversibly store Li by plating on the Li electrode underneath the SEI18,19,27. The

nucleation overpotential is the magnitude of the voltage spike at the onset of Li deposition as shown in the first five cycles of plating/stripping (insets of Fig. 5a, b). The nucleation

overpotential of AFH-25 is lower than the bare Li. The Sn and Li–Sn alloy in the artificial SEI provide uniform dispersive seeds as a nucleation site for Li deposition. This contributes to

the uniform distribution of Li ions for a homogeneous Li deposition and longer plating/stripping cycles. The plating/stripping hours of SnF2-treated artificial SEI have been improved and

compared to the previously reported literature as summarized in Supplementary Table 3. It is noticed that AFH-25 symmetrical cell shows remarkable long plating/stripping performance with

reduced voltage overpotential. Figure 5c, d shows the average voltage hysteresis that is the difference between the voltage of Li stripping and plating. This is mainly dependent on the

current density and nature of interfacial SEI. The voltage hysteresis of AFH-25 exhibits a more stable and less fluctuating voltage curve compared to the bare Li. The artificial SEI composed

of Sn, LiF, and Sn–Li alloy lowers the practical current density and reduces the _R_ct. The reduced hysteresis in AFH-25 symmetric cells indicates a low-voltage polarization voltage profile

in the SnF2-protected Li/NMC111 full cell. Similar improved voltage–time profiles were obtained when plated/stripped at other higher constant current density rates (Supplementary Fig. 7a–c)

and different current density rates (Supplementary Fig. 8a, b). SEM was performed to study the morphology of Li deposition on bare Li and AFH-25. Figure 5e–j shows the SEM images of bare Li

and AFH-25 after 1st, 10th, and 100th plating at 0.5 mA cm−2 with a capacity of 1 mAh cm−2. The bare Li (Fig. 5e–g) exhibits a large roughness surface with Li dendrites and filament

protruding out in random orientations, suggesting nonuniform Li deposition and uncontrolled growth of Li dendrites. This leads to dead and mossy Li upon cycling on bare Li, attributed to the

continuous corrosion of reactive Li and electrolyte consumption. These cause the whim of increased voltage and impedance. The sharp spikes of Li dendrites can pierce the separator

threatening safety. As a result, premature failure of the cell is more pronounced. In contrast, AFH-25 (Fig. 5h–j) exhibits a flat, smooth surface without obvious dendritic or mossy Li. The

compact and uniform artificial layer serves as a physical protection barrier to inhibit the penetration of organic electrolyte and subsequent corrosion of the underlying Li electrode. In

addition, the SEI components Sn and Sn–Li alloy reversibly store Li by alloying as Li5Sn2. The insulating SEI component LiF is unfavorable for Li nucleation that facilitates Li-ion diffusion

and store Li by plating on the Li electrode underneath, which leads to a uniform and smooth Li deposition17,18,19,20,21,22. Moreover, Young’s modulus (55.60 GPa) of the artificial SEI layer

is much higher than the threshold value of 6 GPa to suppress the growing Li dendrites63. Therefore, an extremely long and stable cycling performance with reduced overpotential has been

achieved. To study the composition and distribution of elements on the surface of bare Li and AFH-25 after 1st plating at 0.5 mA cm−2, EDS and elemental mapping were performed (Supplementary

Fig. 9a, b). The top-view SEM image of AFH-25 has 28.92 wt% fluorine (F), which is higher than the bare Li at 20.92 wt%. This verifies that excess fluorine came from the dissociation of

SnF2 anions. In addition, the top-view SEM image showed that AFH-25 has uniform elemental mapping distribution of C, O, F, P, and Sn, suggesting a uniform coverage of SEI components. In

contrast, the bare Li shows a nonuniform elemental mapping distribution and inhomogeneous Li deposition. Supplementary Fig. 10a, b shows the cross-sectional SEM images of the bare Li and

AFH-25 after 100th plating at 0.5 mA cm−2. The SEI thickness increases from 0 µm to ~120 µm in bare Li and from 25 µm to ~60 µm for AFH-25 after 100th plating. On the bare Li, the

irreversibly plated Li in each cycle forms an unstable, thicker, and insulating SEI layer retarding the Li-ion transport. The gradually increasing thickness of the SEI layer further

increases the cell’s impedances and eventually causes the cell to die20. However, in the AFH-25, a thinner and denser layer of SEI was observed due to the stable SEI as well as effective

control of consumption of Li and electrolyte32. BATTERY PERFORMANCE To evaluate the potential application and feasibility of AFH-25 anode in practical batteries, NMC111 cathode (loading =

11.88 mg cm−2) was adopted to assemble a full LMB. Figure 6a shows the cycling performance of full cell using bare Li and AFH-25 as an anode at a constant current density of 1 C. The initial

3rd discharge capacity of AFH-25/NMC111 cell is 130.86 mAh g−1 and still remains 104.71 mAh g−1 at 150th cycles, retaining 80.01%. In contrast, the 3rd specific discharge capacity of bare

Li/NMC111 full cell shows a sharp decrease from 132.20 mAh g−1 to 79.59 mAh g−1, retaining 60.20% at the 150th cycle. The superior discharge capacity in long-term cycling demonstrates the

SnF2 treatment is an effective way to achieve outstanding cell stability. The bare Li/NMC111 and AFH-25/NMC111 show the 1st CE of 81.33% and 83.31%, respectively. The lower CE in bare

Li/NMC111 can be attributed to the side reactions and formation of unstable and fragile SEI, while AFH-25/NMC111 exhibits stabilized SEI. With higher cycling, the CE in both full cells

remains above ~99%. In addition, the cycling performance of artificially fluorinated hybrid protected Li anode at a lower N/P ratio of 2:1 was studied (details in Supplementary Fig. 11). The

NMC111 cathode coupled with protected Li anode shows improved cycling performance compared to the unprotected Li. Electrochemical voltage profiles (Fig. 6b, c) show that polarizing voltages

of the full cell using the bare Li and AFH-25 anode is almost the same at the beginning cycles. The rapid increase in polarizing voltages with cycling (Fig. 6b) as observed in the bare Li

was attributed to the unstable SEI. However, a significantly reduced overpotential was observed (Fig. 6c) with AFH-25/NMC111 configuration even after long cycles (e.g., the 150th cycle) due

to the stabilized SEI formation. Figure 6d shows the cycling performance of full cells at different current rates. At a higher rate of 5 C, the specific charge/discharge capacity at the 23rd

cycle using AFH-25 and bare Li was 100.54/100.44 mAh g−1 and 85.29/84.60 mAh g−1, respectively. The capacities at different rates are summarized in Supplementary Table 4. The higher

capacity at higher rates was achieved using AFH-25 than bare Li as an anode. This is in good agreement with symmetrical cell tests and impedance measurements. Figure 6e, f shows the

corresponding charge/discharge voltage profiles at different rates. The significant reduction in voltage hysteresis was observed using AFH-25 as an anode. This is attributed to the

stabilized artificial SEI of AFH-25 that effectively prevents the parasitic reactions between Li and electrolyte and render uniform dendrite-free Li deposition17. On one hand, LiF is poor in

electronic conductivity to prevent electron flow, which suppresses Li dendrite growth16. On the other hand, LiF has high ionic conductivity, low diffusing energy, and high surface energy,

which allow sufficient Li-ion diffusion during plating17,18. Thus, a uniform and dendrite-free morphology of electrodeposited Li was expected on AFH-25 anode. In addition, the Li storage

mechanism by forming reversible Sn–Li alloy and Li plating provides a promising route to develop a stabilized SEI layer25. However, the sharp capacity decay in bare Li/NMC111 is attributed

to the failure of the conductive framework in the anode induced by the highly resistive, fragile, and unstable SEI formation, and dead Li covering Li anode24. The formation of unstable SEI,

loss of Li, and electrolyte consumption due to the high surface area of Li dendrites cause the capacity fading and low CE in the bare Li devices36. Supplementary Fig. 12a, b shows the

Nyquist plots of the full cells using NMC111 as a cathode, bare Li and AFH-25 as an anode, respectively. The _R_ct of the cell using bare Li and AFH-25 as the anode is 189.00 Ω and 12.91 Ω,

respectively. The largely reduced _R_ct of AFH-25 indicates improvement in charge transfer kinetics50. This is attributed to the stabilized SEI consisting of LiF, Sn, and Sn–Li alloy, which

allows sufficient Li-ion diffusion and inhibits undesired side reactions21,25. Supplementary Fig. 12c shows the equivalent circuit for fitting. Impedance results are summarized in

Supplementary Table 5. DISCUSSION An artificial SEI consisting of LiF, Sn, and Sn–Li alloy was constructed by treating Li anode with SnF2-containing electrolyte, whose chemical and

mechanical stability protects the Li from the side reactions and suppresses the Li dendrite growth while allowing for fast Li+ transport and reversible Li–Sn alloying. Outstanding

electrochemical performances were achieved in both Li//Li symmetric and full Li-metal cells based on an NMC111 cathode, as evidenced by long-term plating/stripping stability (~2325 h),

reduced overpotential in the former and excellent cycling stability, high capacity retention of 80.01% and high specific charge/discharge capacity in the latter. This effective approach to

Li-stabilization based on SnF2-induced interphase opens an alternative door to the development of high energy density storage devices using not only transition metal oxide cathodes but also

emerging cathode chemistries, such as Li–S and Li–O2. METHODS MATERIALS AND PREPARATIONS Li chips with a diameter of 15.6 mm and thickness 250 µm were purchased from Xiamen Tmax, China. Tin

(II) fluoride was purchased from Acros Organics. The surface of Li chips was cleaned and polished with a sharp blade in order to remove the impurities and oxide layer. Different wt% of SnF2

was mixed in 1 M LiPF6 in a mixture solvent of ethylene carbonate (EC)/diethylcarbonate (DEC; 1:1 v/v) and partially dissolved SnF2 solution was ultrasonicated each time before drop-casting.

A volume of 30 µL of electrolyte-containing different wt% SnF2 was dropped cast on the surface of Li that changed from the silver shiny color to immediate dark gray. After drying for ~48 h

at 60 °C inside an Ar glove box, the surface becomes whitish color and the surface of the electrodes were rinsed with dimethyl carbonate solvent to remove any residues. Both the bare Li and

the Li treated with SnF2 were cut into a 12 mm circular disc. ELECTRODE FABRICATION The cathode used was Li nickel cobalt manganese oxide (LiNi1/3Co1/3Mn1/3O2) or (NMC111), with the areal

mass loading of the electrode 11.88 mg cm−2 and active material 9.98 mg cm−2. The diameter of the cathode electrodes was 12 mm. MATERIALS CHARACTERIZATIONS A sealed container was used to

avoid direct contact with moisture or air while transferring the samples from the glove box during material characterizations. SEM images, EDS, and elemental mapping were performed using

Hitachi S-3400N SEM and Hitachi S-4700N FESEM. The XRD was conducted using a Rigaku SmartLab diffractometer. All the samples were encapsulated with Kapton tape during XRD measurement to

avoid moisture contamination. XPS was performed on the Thermo Scientific X-ray Photoelectron Spectrometer with Al Ka radiation. The surface morphology and Young’s modulus measurement of bare

Li and SnF2-treated Li was carried out using Bruker AFM equipped with the MAC III controller using RTESPA-525 tip with a resonant frequency of 75 kHz through quantitative nanomechanical

mode. The contact angle was measured by VCA2000 video contact angle system. ELECTROCHEMICAL CHARACTERIZATION Symmetric cells and full cells were assembled in the Ar glove box using bare Li

and protected Li as anode using CR-2032 coin-type cells. A volume of 60 µL of 1 M LiPF6 in the mixture of EC/DEC (1:1 v/v) was used as the electrolyte and Celgard 2500 film of 25 µm

thickness as the separator. The galvanostatic charge–discharge measurements of the coin cells were carried out using the LAND CT2001A system. Plating/stripping of the symmetrical cells was

performed at various areal current density from 0.5 to 5 mA cm−2 to achieve various areal capacities from 1 to 3 mAh cm−2. Full cells were cycled between 2.7 V to 4.2 V at a constant current

density of 1 C and at various current density rates from 0.1 C, 0.2 C, 1 C, 3 C, and 5 C for every five cycles and followed back to 0.1 C. EIS measurement was conducted by an

electrochemical workstation (Ametek VERSATAT3-200 potentiostat) with a 10 mV amplitude AC signal with frequency ranging from 100 kHz to 0.1 Hz. DATA AVAILABILITY The authors declare that all

the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article and its Supplementary Information or from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. REFERENCES *

Bruce, P. G., Freunberger, S. A., Hardwick, L. J. & Tarascon, J. M. Li-O2 and Li-S batteries with high energy storage. _Nat. Mater._ 11, 19 (2012). Article ADS CAS Google Scholar *

Gurung, A. & Qiao, Q. Solar charging batteries: advances, challenges, and opportunities. _Joule_ 2, 1217–1230 (2018). Article CAS Google Scholar * Gurung, A. et al. Highly efficient

perovskite solar cell photocharging of lithium ion battery using DC–DC booster. _Adv. Energy Mater._ 7, 1602105 (2017). Article CAS Google Scholar * Zhou, Z. et al. Binder free

hierarchical mesoporous carbon foam for high performance lithium ion battery. _Sci. Rep._ 7, 1440 (2017). Article ADS PubMed PubMed Central CAS Google Scholar * Harry, K. J., Hallinan,

D. T., Parkinson, D. Y., MacDowell, A. A. & Balsara, N. P. Detection of subsurface structures underneath dendrites formed on cycled lithium metal electrodes. _Nat. Mater._ 13, 69

(2014). Article ADS CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Albertus, P., Babinec, S., Litzelman, S. & Newman, A. Status and challenges in enabling the lithium metal electrode for high-energy

and low-cost rechargeable batteries. _Nat. Energy_ 3, 16 (2018). Article ADS CAS Google Scholar * Yang, C. P., Yin, Y. X., Zhang, S. F., Li, N. W. & Guo, Y. G. Accommodating lithium

into 3D current collectors with a submicron skeleton towards long-life lithium metal anodes. _Nat. Commun._ 6, 8058 (2015). Article ADS CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Wu, H., Zhuo, D.,

Kong, D. & Cui, Y. Improving battery safety by early detection of internal shorting with a bifunctional separator. _Nat. Commun._ 5, 5193 (2014). Article ADS CAS PubMed Google

Scholar * Liu, K. et al. Extending the life of lithium-based rechargeable batteries by reaction of lithium dendrites with a novel silica nanoparticle sandwiched separator. _Adv. Mater._ 29,

1603987 (2017). Article CAS Google Scholar * Jin, Y. et al. An intermediate temperature garnet-type solid electrolyte-based molten lithium battery for grid energy storage. _Nat. Energy_

3, 732 (2018). Article ADS CAS Google Scholar * Naderi, R. et al. Activation of passive nanofillers in composite polymer electrolyte for higher performance lithium-ion batteries. _Adv.

Sustain. Syst._ 1, 1700043 (2017). Article CAS Google Scholar * McGraw, M. et al. One-step solid-state in-situ thermal polymerization of silicon-PEDOT nanocomposites for the application

in lithium-ion battery anodes. _Polym. (Guildf.)._ 99, 488–495 (2016). Article CAS Google Scholar * Liu, Y. et al. An ultrastrong double-layer nanodiamond interface for stable lithium

metal anodes. _Joule_ 2, 1595–1609 (2018). Article CAS Google Scholar * Lin, D. et al. Three-dimensional stable lithium metal anode with nanoscale lithium islands embedded in ionically

conductive solid matrix. _Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA_ 114, 4613–4618 (2017). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Ding, F. et al. Dendrite-free lithium deposition via

self-healing electrostatic shield mechanism. _J. Am. Chem. Soc._ 135, 4450–4456 (2013). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Pan, J., Cheng, Y. T. & Qi, Y. General method to predict

voltage-dependent ionic conduction in a solid electrolyte coating on electrodes. _Phys. Rev. B_ 91, 134116 (2015). Article ADS CAS Google Scholar * Lu, Y., Tu, Z. & Archer, L. A.

Stable lithium electrodeposition in liquid and nanoporous solid electrolytes. _Nat. Mater._ 13, 961 (2014). Article ADS CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Yuan, Y. et al. Regulating Li

deposition by constructing LiF-rich host for dendrite-free lithium metal anode. _Energy Storage Mater._ 16, 411–418 (2019). Article Google Scholar * Choudhury, S. & Archer, L. A.

Lithium fluoride additives for stable cycling of lithium batteries at high current densities. _Adv. Electron. Mater._ 2, 1500246 (2016). Article CAS Google Scholar * Yan, C. et al. An

armored mixed conductor interphase on a dendrite-free lithium-metal anode. _Adv. Mater._ 30, 1804461 (2018). Article CAS Google Scholar * Zhao, J. et al. Surface fluorination of reactive

battery anode materials for enhanced stability. _J. Am. Chem. Soc._ 139, 11550–11558 (2017). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Fan, X. et al. Fluorinated solid electrolyte interphase

enables highly reversible solid-state Li metal battery. _Sci. Adv._ 4, eaau9245 (2018). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Kanamura, K., Shiraishi, S. & Takehara, Z.

I. Electrochemical deposition of very smooth lithium using nonaqueous electrolytes containing HF. _J. Electrochem. Soc._ 143, 2187–2197 (1996). Article CAS Google Scholar * Zhang, X. Q.,

Cheng, X. B., Chen, X., Yan, C. & Zhang, Q. Fluoroethylene carbonate additives to render uniform Li deposits in lithium metal batteries. _Adv. Funct. Mater._ 27, 1605989 (2017). Article

CAS Google Scholar * Tu, Z. et al. Fast ion transport at solid–solid interfaces in hybrid battery anodes. _Nat. Energy_ 3, 310 (2018). Article ADS CAS Google Scholar * Choudhury, S.

et al. Electroless formation of hybrid lithium anodes for fast interfacial ion transport. _Angew. Chem. Int. Ed._ 56, 13070–13077 (2017). Article CAS Google Scholar * Liang, X. et al. A

facile surface chemistry route to a stabilized lithium metal anode. _Nat. Energy_ 2, 17119 (2017). Article ADS CAS Google Scholar * Yan, K. et al. Selective deposition and stable

encapsulation of lithium through heterogeneous seeded growth. _Nat. Energy_ 1, 16010 (2016). Article ADS CAS Google Scholar * Zhang, L., Zhang, K., Shi, Z. & Zhang, S. LiF as an

artificial SEI layer to enhance the high-temperature cycle performance of Li4Ti5O12. _Langmuir_ 33, 11164–11169 (2017). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Seyring, M. et al. Phase

formation in the ternary systems Li-Sn-C and Li-Sn-Si. _Thermochim. Acta_ 659, 34–38 (2018). Article CAS Google Scholar * Lin, D. et al. Layered reduced graphene oxide with nanoscale

interlayer gaps as a stable host for lithium metal anodes. _Nat. Nanotechnol._ 11, 626 (2016). Article ADS CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Pathak, R. et al. Ultrathin bilayer of

graphite/SiO2 as solid interface for reviving Li metal anode. _Adv. Energy Mater._ 9, 1901486 (2019). Article CAS Google Scholar * Gaikwad, A. M. et al. A high areal capacity flexible

lithium-ion battery with a strain-compliant design. _Adv. Energy Mater._ 5, 1401389 (2015). Article CAS Google Scholar * Chen, Z. et al. Fast and reversible thermoresponsive polymer

switching materials for safer batteries. _Nat. Energy_ 1, 15009 (2016). Article ADS CAS Google Scholar * Wu, F. et al. Comparison of performance and optoelectronic processes in ZnO and

TiO2 nanorod array-based hybrid solar cells. _Appl. Surf. Sci._ 456, 124–132 (2018). Article ADS CAS Google Scholar * Cha, E. et al. 2D MoS2 as an efficient protective layer for lithium

metal anodes in high-performance Li-S batteries. _Nat. Nanotechnol._ 13, 521–521 (2018). Article ADS CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Liu, Y. et al. An artificial solid electrolyte

interphase with high Li-ion conductivity, mechanical strength, and flexibility for stable lithium metal anodes. _Adv. Mater._ 29, 1605531 (2017). Article CAS Google Scholar * Li, N. W.,

Yin, Y. X., Yang, C. P. & Guo, Y. G. An artificial solid electrolyte interphase layer for stable lithium metal anodes. _Adv. Mater._ 28, 1853–1858 (2016). Article CAS PubMed Google

Scholar * Chen, K. et al. Flower-shaped lithium nitride as a protective layer via facile plasma activation for stable lithium metal anodes. _Energy Storage Mater._ 18, 389–396 (2019).

Article Google Scholar * Gunceler, D., Letchworth-Weaver, K., Sundararaman, R., Schwarz, K. A. & Arias, T. The importance of nonlinear fluid response in joint density-functional theory

studies of battery systems. _Modell. Simul. Mater. Sci. Eng._ 21, 074005 (2013). Article ADS Google Scholar * Ma, L., Kim, M. S. & Archer, L. A. Stable artificial solid electrolyte

interphases for lithium batteries. _Chem. Mater._ 29, 4181–4189 (2017). Article CAS Google Scholar * Chen, Q. et al. Electrochemically induced highly ion conductive porous scaffolds to

stabilize lithium deposition for lithium metal anodes. _J. Mater. Chem. A_ 7, 11683–11689 (2019). Article CAS Google Scholar * Ouyang, M. et al. Low temperature aging mechanism

identification and lithium deposition in a large format lithium iron phosphate battery for different charge profiles. _J. Power Source_ 286, 309–320 (2015). Article ADS CAS Google Scholar

* An, Y. et al. Vacuum distillation derived 3D porous current collector for stable lithium-metal batteries. _Nano Energy_ 47, 503–511 (2018). Article CAS Google Scholar * Zheng, X. et

al. Toward a stable sodium metal anode in carbonate electrolyte: a compact, inorganic alloy interface. _J. Phys. Chem. Lett._ 10, 707–714 (2019). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar *

Zhang, S. S., Fan, X. & Wang, C. A tin-plated copper substrate for efficient cycling of lithium metal in an anode-free rechargeable lithium battery. _Electrochim. Acta_ 258, 1201–1207

(2017). Article CAS Google Scholar * Xu, Q., Yang, Y. & Shao, H. Substrate effects on Li+ electrodeposition in Li secondary batteries with a competitive kinetics model. _Phys. Chem.

Chem. Phys._ 17, 20398–20406 (2015). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Liu, W. et al. Enhancing ionic conductivity in composite polymer electrolytes with well-aligned ceramic

nanowires. _Nat. Energy_ 2, 17035 (2017). Article ADS CAS Google Scholar * Gu, C., Mai, Y., Zhou, J., You, Y. & Tu, J. Non-aqueous electrodeposition of porous tin-based film as an

anode for lithium-ion battery. _J. Power Source_ 214, 200–207 (2012). Article ADS CAS Google Scholar * Pathak, R. et al. Self-recovery in Li-metal hybrid lithium-ion batteries via WO3

reduction. _Nanoscale_ 10, 15956–15966 (2018). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Wang, H., Lin, D., Liu, Y., Li, Y. & Cui, Y. Ultrahigh-current density anodes with interconnected

Li metal reservoir through overlithiation of mesoporous AlF3 framework. _Sci. Adv._ 3, e1701301 (2017). Article ADS PubMed PubMed Central CAS Google Scholar * Li, C. et al.

Two-dimensional molecular brush-functionalized porous bilayer composite separators toward ultrastable high-current density lithium metal anodes. _Nat. Commun._ 10, 1363 (2019). Article ADS

PubMed PubMed Central CAS Google Scholar * Shin, H., Park, J., Han, S., Sastry, A. M. & Lu, W. Component-/structure-dependent elasticity of solid electrolyte interphase layer in

Li-ion batteries: experimental and computational studies. _J. Power Source_ 277, 169–179 (2015). Article ADS CAS Google Scholar * Dong, H. et al. Compression of lithium fluoride to 92

GPa. _High. Press. Res._ 34, 39–48 (2014). Article ADS Google Scholar * Zhang, X. et al. Self-suppression of lithium dendrite in all-solid-state lithium metal batteries with poly

(vinylidene difluoride)-based solid electrolytes. _Adv. Mater._ 31, 1806082 (2019). Article CAS Google Scholar * Smirnov, N. Ab initio calculations of the thermodynamic properties of LiF

crystal. _Phys. Rev. B_ 83, 014109 (2011). Article ADS CAS Google Scholar * Stournara, M. E., Guduru, P. R. & Shenoy, V. B. Elastic behavior of crystalline Li-Sn phases with

increasing Li concentration. _J. Power Source_ 208, 165–169 (2012). Article ADS CAS Google Scholar * Qaiser, N., Kim, Y. J., Hong, C. S. & Han, S. M. Numerical modeling of

fracture-resistant Sn micropillars as anode for lithium ion batteries. _J. Phys. Chem. C_ 120, 6953–6962 (2016). Article CAS Google Scholar * Chen, J. et al. Mechanical analysis and in

situ structural and morphological evaluation of Ni–Sn alloy anodes for Li ion batteries. _J. Phys. D Appl. Phys._ 41, 025302 (2007). Article ADS CAS Google Scholar * Wang, J.,

Chen-Wiegart, Y. C. K. & Wang, J. In situ three-dimensional synchrotron X-ray nanotomography of the (De) lithiation processes in tin anodes. _Angew. Chem. Int. Ed._ 53, 4460–4464 (2014).

Article CAS Google Scholar * Mukaibo, H., Momma, T., Shacham-Diamand, Y., Osaka, T. & Kodaira, M. In situ stress transition observations of electrodeposited Sn-based anode materials

for lithium-ion secondary batteries. _Electrochem. Solid-State Lett._ 10, A70–A73 (2007). Article CAS Google Scholar * Chou, C.-Y., Lee, M. & Hwang, G. S. A comparative

first-principles study on sodiation of silicon, germanium, and tin for sodium-ion batteries. _J. Phys. Chem. C_ 119, 14843–14850 (2015). Article CAS Google Scholar * Xu, R. et al.

Artificial soft-rigid protective layer for dendrite-free lithium metal anode. _Adv. Funct. Mater._ 28, 1705838 (2018). Article CAS Google Scholar * Zheng, G. et al. Interconnected hollow

carbon nanospheres for stable lithium metal anodes. _Nat. Nanotechnol._ 9, 618 (2014). Article ADS CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Wang, M. et al. Effect of LiFSI concentrations to form

thickness-and modulus-controlled SEI layers on lithium metal anodes. _J. Phys. Chem. C_ 122, 9825–9834 (2018). Article CAS Google Scholar * Lee, H., Lee, D. J., Kim, Y. J., Park, J. K.

& Kim, H. T. A simple composite protective layer coating that enhances the cycling stability of lithium metal batteries. _J. Power Source_ 284, 103–108 (2015). Article ADS CAS Google

Scholar * Zhu, B. et al. Poly (dimethylsiloxane) thin film as a stable interfacial layer for high-performance lithium-metal battery anodes. _Adv. Mater._ 29, 1603755 (2017). Article CAS

Google Scholar * Li, B., Wang, Y. & Yang, S. A material perspective of rechargeable metalliclithium anodes. _Adv. Energy Mater._ 8, 1702296 (2018). Article CAS Google Scholar * Chai,

J. et al. Dendrite-free lithium deposition via flexible-rigid coupling composite network for LiNi0.5Mn1.5O4/Li metal batteries. _Small_ 14, 1802244 (2018). Article CAS Google Scholar

Download references ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This work has been supported by NSF MRI (1428992), NASA EPSCoR (NNX15AM83A), SDBoR Competitive Grant Program, SDBoR R&D Program, and EDA University

Center Program (ED18DEN3030025). AUTHOR INFORMATION AUTHORS AND AFFILIATIONS * Department of Electrical Engineering and Computer Science, Center for Advanced Photovoltaics and Sustainable

Energy, South Dakota State University, Brookings, SD, 57007, USA Rajesh Pathak, Ke Chen, Ashim Gurung, Khan Mamun Reza, Behzad Bahrami, Jyotshna Pokharel, Abiral Baniya, Wei He, Fan Wu, Yue

Zhou & Qiquan (Quinn) Qiao * School of Science and Key Lab of Optoelectronic Materials and Devices, Huzhou University, Huzhou, People’s Republic of China Fan Wu * Electrochemistry

Branch, Sensor and Electron Devices Directorate, Power and Energy Division, U.S. Army Research Laboratory, Adelphi, MD, 20783, USA Kang Xu Authors * Rajesh Pathak View author publications

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Ke Chen View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Ashim Gurung View author

publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Khan Mamun Reza View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Behzad

Bahrami View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Jyotshna Pokharel View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google

Scholar * Abiral Baniya View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Wei He View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed

Google Scholar * Fan Wu View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Yue Zhou View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed

Google Scholar * Kang Xu View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Qiquan (Quinn) Qiao View author publications You can also search for this

author inPubMed Google Scholar CONTRIBUTIONS R.P. conceived the original concept, designed the experiments, performed electrochemical characterizations, and wrote the paper. K.C., K.M.R.,

and B.B. assisted in material characterizations. K.C., A.G., J.P., A.B., W.H., and F.W. assisted in the interpretation of results. Y.Z., K.X., and Q.Q. supervized the work. All authors have

discussed the paper. CORRESPONDING AUTHORS Correspondence to Yue Zhou, Kang Xu or Qiquan (Quinn) Qiao. ETHICS DECLARATIONS COMPETING INTERESTS The authors declare no competing interests.

ADDITIONAL INFORMATION PEER REVIEW INFORMATION _Nature Communications_ thanks Zhengyuan Tu and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

PUBLISHER’S NOTE Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION

RIGHTS AND PERMISSIONS OPEN ACCESS This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and

reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes

were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If

material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain

permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. Reprints and permissions ABOUT THIS ARTICLE CITE THIS

ARTICLE Pathak, R., Chen, K., Gurung, A. _et al._ Fluorinated hybrid solid-electrolyte-interphase for dendrite-free lithium deposition. _Nat Commun_ 11, 93 (2020).

https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-019-13774-2 Download citation * Received: 06 August 2019 * Accepted: 07 November 2019 * Published: 03 January 2020 * DOI:

https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-019-13774-2 SHARE THIS ARTICLE Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content: Get shareable link Sorry, a shareable link is not

currently available for this article. Copy to clipboard Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative