A systematic review of questionnaires measuring asthma control in children in a primary care population

- Select a language for the TTS:

- UK English Female

- UK English Male

- US English Female

- US English Male

- Australian Female

- Australian Male

- Language selected: (auto detect) - EN

Play all audios:

ABSTRACT Several questionnaires are used to measure asthma control in children. The most appropriate tool for use in primary care is not defined. In this systematic review, we evaluated

questionnaires used to measure asthma control in children in primary care and determined their usefulness in asthma management. Searches were performed in the MEDLINE, Embase, Web of

Science, Google Scholar and Cochrane databases with end date 24 June 2022. The study population comprised children aged 5–18 years with asthma. Three reviewers independently screened studies

and extracted data. The methodological quality of the studies was assessed, using the COSMIN criteria for the measurement properties of health status questionnaires. Studies conducted in

primary care were included if a minimum of two questionnaires were compared. Studies in secondary or tertiary care and studies of quality-of-life questionnaires were excluded. Heterogeneity

precluded meta-analysis. Five publications were included: four observational studies and one sub-study of a randomized controlled trial. A total of 806 children were included (aged 5–18

years). We evaluated the Asthma Control Test (ACT), childhood Asthma Control Test (c-ACT), Asthma APGAR system, NAEPP criteria and Royal College of Physicians’ ‘3 questions’ (RCP3Q). These

questionnaires assess different symptoms and domains. The quality of most of the studies was rated ‘intermediate’ or ‘poor’. The majority of the evaluated questionnaires do not show

substantial agreement with one another, which makes a comparison challenging. Based on the current review, we suggest that the Asthma APGAR system seems promising as a questionnaire for

determining asthma control in children in primary care. SIMILAR CONTENT BEING VIEWED BY OTHERS THE EFFECT OF ALLERGIC RHINITIS TREATMENT ON ASTHMA CONTROL: A SYSTEMATIC REVIEW Article Open

access 17 January 2025 IMPACT OF ASTHMA CONTROL ON QUALITY OF LIFE AMONG PALESTINIAN CHILDREN Article Open access 27 February 2025 EFFICACY AND FEASIBILITY OF THE BREATHE ASTHMA INTERVENTION

WITH AMERICAN INDIAN CHILDREN: A RANDOMIZED CONTROLLED TRIAL Article Open access 08 December 2022 INTRODUCTION Asthma is a chronic pulmonary disease. It is characterized by wheezing,

coughing, dyspnea and airway inflammation1. In children, asthma is the most prevalent chronic disease in primary care. The estimated prevalence of childhood asthma in Dutch primary care is

6.1%2 and prevalence in children is increasing3. Asthma control is defined as the extent to which the effects of the disease can be seen in the patient, or have been reduced or removed by

treatment4,5. It comprises two domains: symptom control and the future risk of adverse outcomes6. The assessment of asthma control is based on the presence of symptoms, limitations on

activities and the use of rescue medication6. A significant proportion of pediatric asthma patients in primary care have suboptimal or uncontrolled asthma, which is associated with a

decreased health-related quality of life (HRQL)7,8. It is important to determine asthma control because this provides insight into the burden of the disease and helps clinicians to decide on

the best treatment strategy. In addition to clinical tests such as spirometry, several questionnaires have been developed to measure asthma control. Frequently used instruments to measure

asthma control in children are the Asthma Control Questionnaire (ACQ), the Asthma Control Test (ACT) and the Childhood Asthma Control Test (C-ACT). These questionnaires have been extensively

evaluated, validated and compared in secondary and tertiary care settings9,10,11,12,13,14,15. A limited number of studies have been conducted in primary care, and these studies mainly

focused on adults15,16,17,18. In the primary care guidelines on pediatric asthma, asthma control as determined by the Global Strategy for Asthma Management and Prevention (GINA) guidelines6

is an important determinant of treatment19. It is important to use a tool that is reliable and easily identifies children with adverse outcomes who may benefit from a change in medication.

Because General Practitioners (GPs) only have limited time available for each consultation, questionnaires should not take too much time to administer. Despite the numerous studies of asthma

control tests, the most appropriate tool for use in primary care has not yet been identified. In this review, we aim to compare the psychometric properties of asthma control questionnaires

used in primary care. We compared these questionnaires regarding: 1) the symptoms and domains evaluated; 2) the characteristics of the questionnaires; 3) an assessment of their quality; 4)

the agreement or correlation in their determination of asthma control; 5) the ability to detect uncontrolled asthma; and 6) the ability to predict future events. By evaluating these

characteristics, we aim to determine the usefulness of these questionnaires in asthma management in children in primary care. METHODS IDENTIFICATION AND SELECTION OF THE LITERATURE A

systematic literature search (without start date limitation and with end date 24 June 2022) was conducted in the MEDLINE, Embase, Web of Science, Google Scholar and Cochrane databases. In

collaboration with a medical librarian specialized in literature searches, we searched for the elements ‘Asthma’, ‘Child’, ‘Questionnaires’ and ‘Comparison’ OR ‘Primary care’. These elements

were converted into keywords (MeSH terms and Emtree terms) and words in the title and abstract. Case reports, conference abstracts, letters and editorials were excluded. No filter was used

by language or date (see Supplementary Information file for the search documents). This trial was prospectively registered in the PROSPERO register under registration number CRD42019122793.

Titles and abstracts found using the search strategy were screened independently by three reviewers (SB, MR and AB). In the initial protocol we stated that we would include studies on

children aged 6 years and older. However, because many studies use the age of 5 years as the lower limit of the age categories, we changed our lower age limit to 5 years. Papers were

included for full-text analysis if they described a study in children with asthma (as defined in the criteria below), aged 5–18 years, in primary care. A minimum of two tools or

questionnaires to determine asthma control had to be compared. Full papers were retrieved if the abstract provided insufficient information or if the paper met the criteria of the first

screening. The reference lists of all the selected publications were checked for additional relevant publications. Disagreements were resolved by consensus or by consulting a fourth reviewer

(GE). The extracted data included the setting, design, study population and outcome measures. We extracted information from the included studies on the development and the purpose of the

questionnaires. We derived information on the ability to detect uncontrolled asthma from the included studies. If no information was available, we searched for the information in the initial

validation study of the questionnaire. These studies could also be conducted in secondary or tertiary care. The methodological quality was assessed by two independent reviewers using the

COSMIN quality criteria for the measurement properties of health status questionnaires, which are based on international consensus20. Questionnaires were scored for the following domains

(when applicable): content validity, internal consistency, criterion validity, construct validity, reproducibility (agreement and reliability), responsiveness, floor and ceiling effects and

interpretability. Studies had to meet the following criteria: * The study design was a randomized controlled trial, cross-sectional study, prospective cohort or study with case-control

questionnaires (self-administered, parent-administered and interviewer-administered questionnaires were all included). * The participants were children aged 5–18 years with a confirmed

diagnosis of asthma. Asthma was defined as satisfaction of one or more of the following criteria: * Doctor’s diagnosis of asthma (‘clinician-diagnosed asthma’). * Coded as having a diagnosis

of asthma (e.g. International Classification of Primary Care (ICPC) read codes). * More than one of the following symptoms: wheezing, breathlessness, chest tightness, cough, reversibility

of FEV1 > 12% in spirometry. * The use of inhaled corticosteroids (ICS) because of asthma symptoms. * The study was conducted in primary care or in a primary care population. * The

article was in English, Dutch or Spanish. * The outcome measures were of the following types: results of validated questionnaires in children describing asthma control, or asthma control

measured by a tool developed by a national guideline organization. Both structured tools (e.g. C-ACT) and unstructured tools (e.g. VAS) were included. * Studies with children and adults were

included if a subgroup analysis was conducted for children below 18 years. Studies were excluded if they: * Described questionnaires to measure asthma control in terms of quality of life. *

Compared different ways to administer a questionnaire to measure asthma control (for example: interviewer version vs. written questionnaire vs. electronic questionnaire, or parent vs.

child). * Compared one single questionnaire with a clinical test for measuring asthma control (such as spirometry or fractional nitric oxide concentration measurements in exhaled breath).

The extracted information included: 1) the symptoms and domains evaluated; 2) the characteristics of the questionnaires; 3) a quality assessment; 4) the agreement or correlation in

determination of asthma control; 5) the ability to detect uncontrolled asthma and thereby identify the children who would benefit from a change in therapy; 6) the ability to predict future

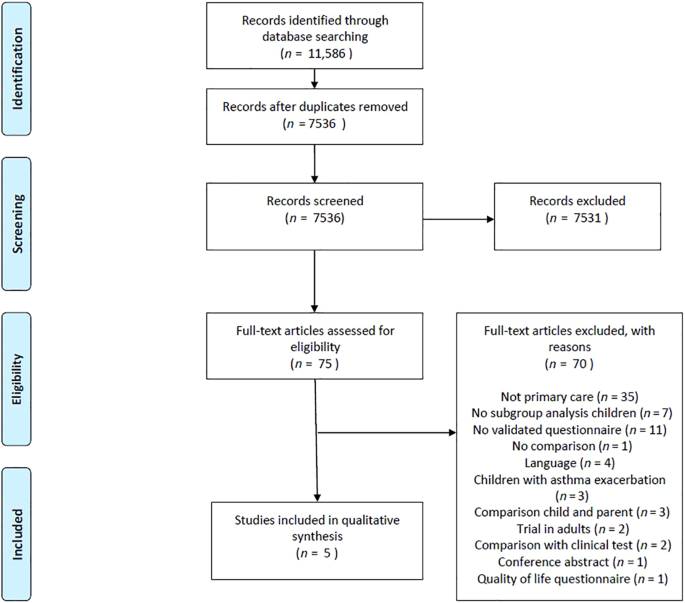

events. REPORTING SUMMARY Further information on research design is available in the Nature Research Reporting Summary linked to this article. RESULTS The search strategy yielded 7536

records, of which 75 were eligible for inclusion based on the title and abstract. The remaining 7461 records were excluded for various reasons, e.g. the study did not concern asthma, the

study concerned the treatment of adult asthma patients or the study evaluated quality-of-life questionnaires. We screened full-text versions of the 75 eligible articles. Five publications

were ultimately included. Figure 1 shows a PRISMA flowchart of the process of identification and inclusion of studies for the current review. The five studies selected for this review had a

total of 1085 participants (range 35–468). The age of the participants varied from 5 to 71 years. A total of 806 children were included in the studies. Four studies had an observational

design. The fifth study, by Rank et al., was a sub-study of a randomized controlled trial. Three studies were conducted in the United Kingdom (UK)21,22,23 and two in the United States of

America (USA)24,25. Two studies also included adult patients (55.3%24 and 57.1% respectively)21; however, subgroup analyses were conducted. Rank et al. conducted their study in twenty24

primary care practices and Andrews et al. in eight23 primary care practices. Halterman et al. recruited patients from three urban clinics and three suburban practices (in the discussion

referred to as ‘primary care offices’)25. The participants in the study by Thomas et al. were recruited from nurse-led asthma clinics at two general practices21. Juniper et al. included

children from five primary care sites and one hospital clinic22. Asthma was defined as ‘clinical diagnoses of asthma’23, ‘documented evidence of asthma’21 or ‘physician-diagnosed’ asthma24.

Halterman et al. included all children who had a diagnosis of asthma and had >2 asthma-related visits in the prior 12 months25. In the study of Juniper et al., children were eligible if

they had well-established and physician-diagnosed asthma, with current symptoms of asthma (ACQ score > 0.5)22. The questionnaires (VAS and NEAPP) were filled in by the parents in the

study by Halterman et al.25. In the study by Thomas et al.21, the questionnaires were administered by a clinician. In the other three studies the questionnaires were filled in by the

children (sometimes together with their parents)22,23,24. Tables 3 and 5 show this information and the main results of the included studies. The studies included in this review were

considered to be too heterogeneous (in terms of the questionnaires used, setting and patient categories) to pool the data. Table 1 shows the characteristics of the included studies.

MEASUREMENT CHARACTERISTICS OF THE QUESTIONNAIRES The five studies presented results of the comparison of two or more questionnaires for measuring asthma control21,22,23,24,25. These studies

gave comparisons of the following structured and unstructured questionnaires: Asthma Control Diary (ACD), ACT, ACQ, C-ACT, National Asthma Education and Prevention Program (NAEPP) criteria,

Royal College of Physicians’ ‘three questions’ (RCP3Q), Visual Analog Scale (VAS) and the Asthma APGAR system (APGAR is an acronym for Activities, Persistent, triGGers, Asthma medications

and Response to therapy). The ACD is evaluated in the study by Juniper et al. 22. Since the ACD has not been validated in children, we do not describe this tool. COMPARISON OF QUESTIONNAIRES

SYMPTOMS AND DOMAINS EVALUATED Each questionnaire deals with a different combination of symptoms and domains. Table 2 shows the domains covered. CHARACTERISTICS OF THE QUESTIONNAIRES ASTHMA

CONTROL QUESTIONNAIRE The ACQ score is the mean of seven questions and ranges between 0 (totally controlled) and 6 (severely uncontrolled). The last question of the ACQ concerns the value

of FEV1 and is filled in by a clinician. The ACQ has been validated for children aged 11 years and older26,27,28. For children aged 6–10 it must be administered by a trained interviewer10.

Three shortened versions of the ACQ have been validated as well, but the complete ACQ has the strongest measurement properties28. ASTHMA CONTROL TEST The ACT is a self-administered

questionnaire for children aged 12 years and up. It contains five items29. CHILDHOOD-ASTHMA CONTROL TEST The C-ACT is a seven-item questionnaire that has three questions for parents and four

questions for children. It has been validated in children aged 4–11 years13. ASTHMA APGAR SYSTEM The Asthma APGAR system has recently been developed for use in a primary care population30.

It was developed to be answered by both parents and children together. After they have completed the assessment, an algorithm based on that data guides the clinicians in their treatment

strategy for the patient. The score that corresponds to inadequate asthma control is derived from the National Asthma Education and Prevention Program (NAEPP) guidelines31. NAEPP CRITERIA

The NAEPP guideline-based criteria to assess asthma control are part of the National Asthma Education and Prevention Program in the USA32. This expert panel organization emphasizes the

importance of monitoring asthma control. The level of severity is determined by assessing both impairment and risk. Asthma control is determined per age category (0–4 years, 5–11 years and

≥12 years). ROYAL COLLEGE OF PHYSICIANS’ ‘THREE QUESTIONS’ The Royal College of Physicians in the UK has developed a practical clinical tool containing three questions (RCP3Q) to assess

asthma control in primary care33. It is the most commonly used tool in the UK. The questionnaire was designed by primary and secondary care physicians and patient organizations. It was

designed to be completed by a health-care professional and contains three questions with the answer options ‘Yes’ or ‘No’, with a score of 1 for ‘yes’ and 0 for ‘no’. The total score ranges

between 0 and 3. An RCP3Q score of 0 indicates good asthma control and a score of 2 or 3 indicates poor control34. The UK Quality Outcomes Framework (QOF)35 encourages the use of the RCP3Q

in patients aged 8 and older. The performance of this questionnaire has been evaluated in adults; however, there is limited evidence for the use in children. VISUAL ANALOG SCALE The VAS is

an unstructured method for assessing asthma control in patients. To determine the VAS score, patients (or parents) have to indicate the severity of symptoms by placing an ‘X’ along a 100 mm

line. A score of 0 (X on the left) indicates ‘no symptoms’ and a score of 100 (X on the right) indicates ‘very bad symptoms’. The VAS score is collapsed into quartiles (0–25, 26–50, 51–75,

76–100) corresponding to an ascending level of asthma severity. No cut-off value has been described. Table 3 shows the characteristics of the questionnaires for assessing asthma control that

are included in the current review. Table 4 gives information on the development and the purpose of the questionnaires. QUALITY ASSESSMENT Information on content validity could be derived

from two studies22,24. No information was found on internal consistency. Criterion validity was evaluated in three studies23,24,25. Two studies evaluated construct validity21,22. The aspects

of agreement, reliability and responsiveness were evaluated in one study22. Floor and ceiling effects were rated as poor in three studies21,23,25. All studies scored ‘intermediate’ on

interpretability21,22,23,24,25. Table 6 in the supplementary information file gives a summary of the assessment of the measurement properties of all the questionnaires included in this

review. AGREEMENT IN THE DETERMINATION OF ASTHMA CONTROL The study by Andrews et al. determined the accuracy of the RCP3Q score in predicting asthma control as defined by the ACT or C-ACT

threshold score of 1923. For children aged 5–11, a kappa value of 0.43 for poorly controlled asthma was found, indicating moderate agreement. For children aged 12–16, the kappa value was

0.33, demonstrating fair agreement. Overall, RCP3Q scores correlated moderately with C-ACT and ACT data (Spearman’s rho correlation coefficient was −0.52 and −0.49 respectively). Table 5

shows the agreement between the questionnaires included in the current review. The legend in Table 5 gives the interpretation of the kappa values and correlation values. The study showed

that the RCP3Q’s sensitivity for detecting uncontrolled asthma as defined by ACT of C-ACT ranged from 43% to 60% and the specificity from 80% to 82%. Juniper et al. evaluated the measurement

properties of the ACQ by comparing the results with the RCP3Q in 35 children22. Pearson correlation coefficients between the ACQ and the RCP3Q were determined. The value for cross-sectional

construct validity was 0.52 and the value for longitudinal construct validity was 0.81. Thomas et al. determined the correlation between the RCP3Q and the ACQ in adults and children.

Fifteen children completed seven follow-up visits (over 12 weeks). The cross-sectional correlation coefficient in children was 0.41, however this moderate correlation was not statistically

significant. The longitudinal correlation for children was 0.61 (_p_ < 0.001). This study was an exploratory analysis. Rank et al. tested the effectiveness of the Asthma APGAR system by

comparing this questionnaire with the ACT and C-ACT24. A total of 209 participants in the overall study population were aged under 18 years (=44.7%). For children aged 5–11 years, the C-ACT

and Asthma APGAR instruments were in agreement in 85.8% of the cases (95% CI 78.5–91.4%). The kappa value of 0.716 (95% CI: 0.060–0.84) indicated substantial agreement. In the age group

12–18 years, the two questionnaires were in agreement 81.3% of the time (95% CI 71.0–89.1%). The kappa value of 0.625 (95% CI: 0.45–0.80) indicated substantial agreement as well. Halterman

et al. compared the assessment of asthma control using NAEPP criteria with a VAS. The NAEPP severity classification was used as a gold standard. Both questionnaires were filled in by the

parents. A critical error was defined as ‘if parents reported the child’s symptoms in the lower 50th percentile of severity for VAS, whereas the child had moderate or severe persistent

symptoms according to the NAEPP criteria’. The results showed that 41% of the parents made this so-called ‘critical error’. ABILITY TO DETECT UNCONTROLLED ASTHMA ACT The screening accuracy

of the ACT was evaluated by Nathan et al. 29. The agreement between the ACT and a specialist’s rating of asthma control was determined. A cut-off point of ≤19 resulted in a sensitivity of

69.2% and specificity of 76.2%, with an area under Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve of 0.727. C-ACT The validation study of the C-ACT by Liu et al.13 compared the C-ACT scores

with a specialist’s assessment. It found that a cut-off point of 19 results in a sensitivity of 68% and a specificity of 74% for the detection of uncontrolled asthma. ACQ The study by

Juniper et al. showed that in children whose asthma control changes between clinic visits, the questionnaire was able to detect the change (_p_ < 0.026)22. However, no specific

information can be extracted on the ability of the ACQ to detect uncontrolled asthma. The previous validation study in adults did not provide this information either26. APGAR No detailed

information about the ability to detect uncontrolled asthma of the Asthma APGAR system can be found in the study of Rank at al. 24. The authors did identify an ‘actionable item’ in more than

75% of the children with poor asthma control. NAEPP The NAEPP and ACQ criteria were compared in a study of 373 adolescents with asthma. The NAEPP identified 84.6% of the cases of

uncontrolled asthma and the ACQ 64.6% of the cases11. RCP3Q To analyze the performance of the RCP3Q in detecting uncontrolled asthma, it was compared to C-ACT or ACT, whereby a score of 19

was defined as uncontrolled asthma23. Using a threshold RCP3Q score of ≥2 to predict uncontrolled asthma resulted in a sensitivity of 0.60 and a specificity of 0.82 for the age group 5–11

years, and a sensitivity of 0.51 and specificity of 0.81 for the age group 12–16 years. VAS Halterman compared unstructured assessments of asthma severity (VAS) with the NAEPP classification

of severity. Of the children with moderate to severe symptoms according to the NAEPP classification, 41% of the parents rated their children in the lowest two quartiles of the VAS. The

unstructured method seems to underestimate the severity level of asthma. ABILITY TO PREDICT FUTURE EVENTS None of the questionnaires included in this review provides information on the risk

of future events as an outcome. Previous studies have identified several risk factors for asthma attacks or poor asthma-related outcomes36,37,38. These risk factors include e.g. younger age,

history of hospitalization or an emergency department (ED) visit in the previous year, three days’ use of oral corticosteroids in the previous three months, a lower FEV1/FVC ratio37, higher

FeNO levels and a recent history of asthma attacks38. A recent systematic review concluded that a previous asthma attack was the most strongly predictive factor36. DISCUSSION This is the

first systematic review that evaluated the usefulness of pediatric asthma control questionnaires in a primary care population. Five studies were included. A ‘gold standard’ or reference

standard to determine asthma control in children is lacking. The majority of the evaluated questionnaires do not show substantial agreement with other questionnaires, which makes a

comparison challenging. The studies varied in the asthma definition used, the administration of the questionnaires (by the parents and/or child and clinician), method of statistical

analysis, age range, included domains of asthma control and sample size. Moreover, there were differences in the recall period. Several characteristics make a questionnaire suitable for use

in clinical practice. A convenient asthma control questionnaire for children needs to be relatively quick to complete, able to identify patients with uncontrolled asthma at risk of adverse

outcomes and able to identify patients who would benefit from a different treatment strategy. Based on our evaluation, we conclude that the asthma APGAR system is a promising tool to

determine asthma control in children in primary care. It is specifically designed for use in primary care. It shows good agreement with the validated C-ACT, and no spirometry results are

needed to complete the questionnaire. It may be more time consuming to fill in than the other questionnaires; however, it includes an algorithm that guides the physicians in their management

strategy, which could be more efficient. There is evidence that the introduction of the Asthma APGAR system improves rates of asthma control and reduces asthma-related ED visits, urgent

care and hospital visits39. Since the Asthma APGAR system was only developed recently, it needs further validation before it can be implemented in pediatric asthma management in primary

care. Worth et al. conducted a systematic literature review to identify Patient-Reported Outcome Measures (PROMs) for asthma in adults and children40. The aim of the study was to identify

PROMs for use in research contexts and clinical settings. For children, the only tools included in this review to determine asthma control were the Childhood Asthma Questionnaire (CAQ) and

the C-ACT. The reviewers only included ‘sufficiently well developed and validated questionnaires’. In addition, the results were not specifically for a primary care population. The authors

conclude that the CAQ is poorly validated and the C-ACT requires further validation work as there are doubts as to whether it estimates poor control of asthma accurately. The evaluated

questionnaires show little overlap with the instruments in our study. Another literature review by Voorend-van Bergen et al. explored the usefulness of questionnaires commonly used to

determine asthma control in children41. It described the measurement characteristics of the ACT, C-ACT and ACQ as well as the Asthma Therapy Assessment Questionnaire (ATAQ) and the Test for

Respiratory and Asthma Control in Kids (TRACK). The authors did not conduct a systematic literature search; they merely described commonly used questionnaires. Besides, the study population

was not restricted to primary care. The authors conclude that these tools to determine asthma control may be useful in pediatric asthma management, but they emphasize the need for validation

studies in a wider range of settings. No particular questionnaire is recommended. Measurement characteristics of the RCP3Q questionnaire were described in three articles included in the

current review21,22,23. The correlation with other questionnaires in these studies varied from fair to good. Hoskins et al. assessed the diagnostic performance of the RCP3Q in patients aged

≥13 in primary care using statistical modeling and found that the RCP3Q model provided the best fit. 11% of the subjects were aged 13–19 years. The study was not included in this review

because data for children were not presented separately. The results indicate that the RCP3Q is an effective tool for assessing asthma control in routine review consultations42. However,

since these results concern both adults and children and no subgroup analysis was conducted, it is not clear whether these results apply specifically for children aged 18 years and younger.

The Visual Analog Scale is not widely used in asthma care, but the authors of a previous trial concluded that it could be an effective additional tool in the diagnostic process in children

with exercise-induced asthma (EIA)43. Moreover, a prospective study assessed the value of VAS as a daily monitoring tool in 42 adolescents with asthma44. Patients were recruited from the

emergency department through clinical referrals and with flyers. The authors conclude that the VAS score significantly predicted the results of symptom diary data. These two findings are not

in accordance with the results of Halterman et al.25. One reason for this discrepancy could be the fact that patients in these two studies were recruited from the pediatric emergency

department44 and from an outpatient clinic of the pediatric department43. It seems reasonable to assume that asthma control in children in secondary care is not comparable to asthma control

in a primary care population. Besides, the method for administering the VAS score was different. Lastly, the study of Lammers et al. only included a specific subgroup of children, namely

children with EIA. Although no gold (or reference) standard exists to measure asthma control in children, the GINA criteria are sometimes referred to as such. The performance of the ACT and

ACQ has been compared with the GINA criteria in children in multiple studies9,45,46. These studies all concerned hospital patients with asthma. Koolen et al. concluded that both the ACT and

C-ACT underestimated the proportion of children with uncontrolled asthma as defined by GINA9. The trial by Yu et al. suggests that C-ACT scores and GINA guideline−based asthma control

measures were positively correlated, but that the C-ACT may overestimate asthma control46. O’Byrne et al. used the GINA criteria as a gold standard to determine the accuracy of the ACQ-545.

They found a moderate correlation (kappa value 0.59) for children aged <18 years. None of the studies included in the current review compared a questionnaire with the GINA guidelines.

Since the outcome of the GINA instrument is partly based on spirometry results, this could have influenced the level of agreement between the questionnaires. The different questionnaires

were designed with different purposes and outcomes in mind. The choice of questionnaire to use depends on the intellectual level of the child and parents and the age of the child. In Dutch

primary care, spirometry results are not always available for children, since spirometry in children is not routinely carried out by GPs. Consequently, questionnaires that take into account

spirometry, e.g. the ACQ, GINA and NAEPP criteria, are less appropriate. Alternative tools are the ACT, C-ACT, Asthma APGAR system or shortened versions of the ACQ. The ACT and C-ACT have

been extensively validated in secondary care and are easy to administer13,14,47 The C-ACT displays pictures with facial expressions to represent emotions in relation to the answers. This

could make this questionnaire more appealing and easier to complete for children. The C-ACT contains questions for both the parents and the child. The result of this questionnaire gives an

integral assessment of asthma severity. However, previous trials were only conducted in secondary and tertiary care and suggest that C-ACT may overestimate asthma control9,46. This could

lead to under-treatment, which negatively influences the diagnostic and therapeutic process of pediatric asthma patients. The Asthma APGAR system was designed for use in primary care. It

shows good agreement with the validated ACT and C-ACT and it includes an algorithm for treatment. There are some limitations to this study. First, the quality of most of the studies included

in this review was rated ‘intermediate’ or ‘poor’ (when information was available) rather than ‘positive’. Secondly, not all the questionnaires currently used to determine asthma control in

children are represented in this review. Commonly used tools such as GINA6 and the asthma therapy assessment questionnaire (ATAQ)48 are not described in the current review since there were

no comparative studies of these tools performed in children in primary care. We decided to only include studies with full text in English, Dutch or Spanish, which may have resulted in the

exclusion of articles that fulfilled our other inclusion criteria. One of the strengths of this study is the sensitive search strategy. This resulted in a large number of references.

However, only a small number of studies were included. This reflects the strict inclusion criteria we used to select studies. Studies were only included if it was explicitly stated that the

study was conducted in primary care. Furthermore, studies conducted in children and adults were excluded if no subgroup analysis was performed in children aged under 18. Children younger

than 5 years were not included because the diagnosis of asthma is difficult to confirm in pre-school children49. The present systematic review evaluated five studies that compared

questionnaires used to determine asthma control. Based on the available evidence, we suggest that the Asthma APGAR system could be a promising tool for use by GPs in clinical practice.

However, it needs further validation. More studies are needed to develop a questionnaire that assesses the risk of future events. DATA AVAILABILITY The authors declare that the data

supporting the findings of this study are available within the paper and in the supplementary information file. REFERENCES * Bush, A. & Fleming, L. Diagnosis and management of asthma in

children. _BMJ_ 350, h996 (2015). Article PubMed Google Scholar * Pols, D. H. J., Nielen, M. M. J., Korevaar, J. C., Bindels, P. J. E. & Bohnen, A. M. Reliably estimating prevalences

of atopic children: an epidemiological study in an extensive and representative primary care database. _NPJ Prim. Care Respir. Med._ 27, 23 (2017). Article PubMed PubMed Central Google

Scholar * Eder, W., Ege, M. J. & von Mutius, E. The asthma epidemic. _N. Engl. J. Med._ 355, 2226–2235 (2006). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Reddel, H. K. et al. An official

American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society statement: asthma control and exacerbations: standardizing endpoints for clinical asthma trials and clinical practice. _Am. J. Respir.

Crit. Care Med._ 180, 59–99 (2009). Article PubMed Google Scholar * Taylor, D. R. et al. A new perspective on concepts of asthma severity and control. _Eur. Respir. J._ 32, 545–554

(2008). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Asthma, G. S. F. Global Strategy for Asthma Management and Prevention https://ginasthma.org/ (2021). * Liu, A. H. et al. Status of asthma

control in pediatric primary care: results from the pediatric Asthma Control Characteristics and Prevalence Survey Study (ACCESS). _J. Pediatr._ 157, 276–281.e273 (2010). Article PubMed

Google Scholar * Silva, C. M., Barros, L. & Simoes, F. Health-related quality of life in paediatric asthma: children’s and parents’ perspectives. _Psychol. Health Med._ 20, 940–954

(2015). Article PubMed Google Scholar * Koolen, B. B. et al. Comparing Global Initiative for Asthma (GINA) criteria with the Childhood Asthma Control Test (C-ACT) and Asthma Control Test

(ACT). _Eur. Respir. J._ 38, 561–566 (2011). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Nguyen, J. M. et al. Validation and psychometric properties of the Asthma Control Questionnaire among

children. _J. Allergy Clin. Immunol._ 133, 91–97.e91-96 (2014). Article PubMed Google Scholar * Rhee, H., Love, T. & Mammen, J. Comparing Asthma Control Questionnaire (ACQ) and

National Asthma Education and Prevention Program (NAEPP) asthma control criteria. _Ann. Allergy Asthma Immunol._ 122, 58–64 (2019). Article PubMed Google Scholar * Jia, C. E. et al. The

Asthma Control Test and Asthma Control Questionnaire for assessing asthma control: systematic review and meta-analysis. _J. Allergy Clin. Immunol._ 131, 695–703 (2013). Article PubMed

Google Scholar * Liu, A. H. et al. Development and cross-sectional validation of the Childhood Asthma Control Test. _J. Allergy Clin. Immunol._ 119, 817–825 (2007). Article PubMed Google

Scholar * Bime, C. et al. Measurement characteristics of the childhood Asthma-Control Test and a shortened, child-only version. _NPJ Prim. Care Respir. Med._ 26, 16075 (2016). Article

PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Schatz, M. et al. Asthma Control Test: reliability, validity, and responsiveness in patients not previously followed by asthma specialists. _J.

Allergy Clin. Immunol._ 117, 549–556 (2006). Article PubMed Google Scholar * Zhou, X., Ding, F. M., Lin, J. T. & Yin, K. S. Validity of asthma control test for asthma control

assessment in Chinese primary care settings. _Chest_ 135, 904–910 (2009). Article PubMed Google Scholar * Olaguibel, J. M. et al. Measurement of asthma control according to Global

Initiative for Asthma guidelines: a comparison with the Asthma Control Questionnaire. _Respir. Res._ 13, 50 (2012). Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Sastre, J. et al.

Cut-off points for defining asthma control in three versions of the Asthma Control Questionnaire. _J. Asthma_ 47, 865–870 (2010). Article PubMed Google Scholar * Bindels, P. J. E. et al.

NHG-Standaard Astma bij kinderen (Derde herziening). _Huisarts. Wet._ 57, 70–80 (2014). Google Scholar * Terwee, C. B. et al. Quality criteria were proposed for measurement properties of

health status questionnaires. _J. Clin. Epidemiol._ 60, 34–42 (2007). Article PubMed Google Scholar * Thomas, M., Gruffydd-Jones, K., Stonham, C., Ward, S. & Macfarlane, T. V.

Assessing asthma control in routine clinical practice: use of the Royal College of Physicians ‘3 questions’. _Prim. Care Respir. J._ 18, 83–88 (2009). Article PubMed Google Scholar *

Juniper, E. F., Gruffydd-Jones, K., Ward, S. & Svensson, K. Asthma Control Questionnaire in children: validation, measurement properties, interpretation. _Eur. Respir. J._ 36, 1410–1416

(2010). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Andrews, G., Lo, D. K. H., Richardson, M., Wilson, A. & Gaillard, E. A. Prospective observational cohort study of symptom control

prediction in paediatric asthma by using the Royal College of Physicians three questions. _NPJ Prim. Care Respir. Med._ 28, 39 (2018). Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar *

Rank, M. A., Bertram, S., Wollan, P., Yawn, R. A. & Yawn, B. P. Comparing the Asthma APGAR system and the Asthma Control Test in a multicenter primary care sample. _Mayo Clin. Proc._ 89,

917–925 (2014). Article PubMed Google Scholar * Halterman, J. S. et al. Symptom reporting in childhood asthma: a comparison of assessment methods. _Arch. Dis. Child_ 91, 766–770 (2006).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Juniper, E. F., O’Byrne, P. M., Guyatt, G. H., Ferrie, P. J. & King, D. R. Development and validation of a questionnaire to

measure asthma control. _Eur. Respir. J._ 14, 902–907 (1999). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Juniper, E. F., Bousquet, J., Abetz, L., Bateman, E. D. & Committee, G. Identifying

‘well-controlled’ and ‘not well-controlled’ asthma using the Asthma Control Questionnaire. _Respir. Med._ 100, 616–621 (2006). Article PubMed Google Scholar * Juniper, E. F., Svensson,

K., Mork, A. C. & Stahl, E. Measurement properties and interpretation of three shortened versions of the asthma control questionnaire. _Respir. Med._ 99, 553–558 (2005). Article PubMed

Google Scholar * Nathan, R. A. et al. Development of the asthma control test: a survey for assessing asthma control. _J. Allergy Clin. Immunol._ 113, 59–65 (2004). Article PubMed Google

Scholar * Yawn, B. P., Bertram, S. & Wollan, P. Introduction of Asthma APGAR tools improve asthma management in primary care practices. _J. Asthma Allergy_ 1, 1–10 (2008). Article

PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * National Asthma Education and Prevention Program Expert Panel Report 3 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK7232/ (2007). * National Asthma

Education and Prevention Program Expert Panel Report 3 (EPR-3): guidelines for the diagnosis and management of asthma-summary report 2007. _J. Allergy Clin. Immunol._ 120, S94–S138 (2007).

Article Google Scholar * Pearson, M. G., Bucknall, C. M. (eds) _Measuring clinical outcome in asthma: a patient focused approach_ (Royal College of Physicians, 1999). * Pinnock, H. et al.

Clinical implications of the Royal College of Physicians three questions in routine asthma care: a real-life validation study. _Prim. Care Respir. J._ 21, 288–294 (2012). Article PubMed

PubMed Central Google Scholar * National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. NICE Quality and Outcome Framework indicator.

https://www.nice.org.uk/standards-and-indicators/qofindicators (2017). * Buelo, A. et al. At-risk children with asthma (ARC): a systematic review. _Thorax_ 73, 813–824 (2018). Article

PubMed Google Scholar * Wu, A. C. et al. Predictors of symptoms are different from predictors of severe exacerbations from asthma in children. _Chest_ 140, 100–107 (2011). Article PubMed

PubMed Central Google Scholar * Lo, D. et al. Risk factors for asthma attacks and poor control in children: a prospective observational study in UK primary care. _Arch. Dis. Child_ 107,

26–31 (2022). Article PubMed Google Scholar * Yawn, B. P. et al. Use of asthma APGAR tools in primary care practices: a cluster-randomized controlled trial. _Ann. Fam. Med._ 16, 100–110

(2018). Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Worth, A. et al. Patient-reported outcome measures for asthma: a systematic review. _NPJ Prim. Care Respir. Med._ 24, 14020 (2014).

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Voorend-van Bergen, S., Vaessen-Verberne, A. A., de Jongste, J. C. & Pijnenburg, M. W. Asthma control questionnaires in the management

of asthma in children: a review. _Pediatr. Pulmonol._ 50, 202–208 (2015). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Hoskins, G., Williams, B., Jackson, C., Norman, P. D. & Donnan, P. T.

Assessing asthma control in UK primary care: use of routinely collected prospective observational consultation data to determine appropriateness of a variety of control assessment models.

_BMC Fam. Pr._ 12, 105 (2011). Article Google Scholar * Lammers, N. et al. The Visual Analog Scale detects exercise-induced bronchoconstriction in children with asthma. _J. Asthma_, 57,

1347–1353 (2019). * Rhee, H., Belyea, M. & Mammen, J. Visual analogue scale (VAS) as a monitoring tool for daily changes in asthma symptoms in adolescents: a prospective study. _Allergy

Asthma Clin. Immunol._ 13, 24 (2017). Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * O’Byrne, P. M. et al. Measuring asthma control: a comparison of three classification systems. _Eur.

Respir. J._ 36, 269–276 (2010). Article PubMed Google Scholar * Yu, H. R. et al. Comparison of the global initiative for asthma guideline-based asthma control measure and the childhood

asthma control test in evaluating asthma control in children. _Pediatr. Neonatol._ 51, 273–278 (2010). Article PubMed Google Scholar * Banasiak, N. C. Implementation of the asthma control

test in primary care to improve patient outcomes. _J. Pediatr. Health Care_ 32, 591–599 (2018). Article PubMed Google Scholar * Somashekar, A. R. & Ramakrishnan, K. G. Evaluation of

asthma control in children using childhood- asthma control test (C-ACT) and asthma therapy assessment questionnaire (ATAQ). _Indian Pediatr._ 54, 746–748 (2017). Article CAS PubMed Google

Scholar * Winklerprins, V., Walsworth, D. T. & Coffey, J. C. Clinical Inquiry. How best to diagnose asthma in infants and toddlers? _J. Fam. Pr._ 60, 152–154 (2011). Google Scholar *

Viera, A. J. & Garrett, J. M. Understanding interobserver agreement: the kappa statistic. _Fam. Med._ 37, 360–363 (2005). PubMed Google Scholar * Hinkle, D. E., Wiersma, W. & Jurs,

S. G. _Applied statistics for the behavioral sciences_. Vol. 663 (Houghton Mifflin College Division, 2003). Download references ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This project is funded by ZonMw. AUTHOR

INFORMATION AUTHORS AND AFFILIATIONS * Department of General Practice, Erasmus MC, University Medical Centre Rotterdam, P.O. Box 2040, 3000 CA, Rotterdam, The Netherlands Sara Bousema,

Arthur M. Bohnen, Patrick J. E. Bindels & Gijs Elshout Authors * Sara Bousema View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Arthur M. Bohnen View

author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Patrick J. E. Bindels View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar

* Gijs Elshout View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar CONTRIBUTIONS S.B.: first reviewer of study selection, first author, conducted the quality

assessment of the included studies. A.M.B.: co-author (revised the manuscript several times), second reviewer of study selection, conducted the quality assessment of the included studies.

P.J.E.B.: was involved at the start of the study (formulating research questions and method), co-author (revised the manuscript two times). G.E.: was involved at the start of the study,

co-author (revised the manuscript several times), fourth reviewer (consulted in case of disagreement by the other reviewers). All authors made substantial contributions to the conception or

design of the work or the acquisition, the interpretation of the data. All authors made their contribution in drafting the work or revising it and gave their final approval of the completed

version. All authors take accountability for all aspects of the work. CORRESPONDING AUTHOR Correspondence to Sara Bousema. ETHICS DECLARATIONS COMPETING INTERESTS The authors declare no

competing interests. ADDITIONAL INFORMATION PUBLISHER’S NOTE Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION REPORTING SUMMARY RIGHTS AND PERMISSIONS OPEN ACCESS This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International

License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source,

provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons

license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by

statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. Reprints and permissions ABOUT THIS ARTICLE CITE THIS ARTICLE Bousema, S., Bohnen, A.M., Bindels, P.J.E. _et al._ A systematic review of

questionnaires measuring asthma control in children in a primary care population. _npj Prim. Care Respir. Med._ 33, 25 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41533-023-00344-9 Download citation *

Received: 28 July 2021 * Accepted: 15 May 2023 * Published: 11 July 2023 * DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41533-023-00344-9 SHARE THIS ARTICLE Anyone you share the following link with will be

able to read this content: Get shareable link Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article. Copy to clipboard Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing

initiative