Multivalency ensures persistence of a +tip body at specialized microtubule ends

- Select a language for the TTS:

- UK English Female

- UK English Male

- US English Female

- US English Male

- Australian Female

- Australian Male

- Language selected: (auto detect) - EN

Play all audios:

ABSTRACT Microtubule plus-end tracking proteins (+TIPs) control microtubule specialization and are as such essential for cell division and morphogenesis. Here we investigated interactions

and functions of the budding yeast Kar9 network consisting of the core +TIP proteins Kar9 (functional homologue of APC, MACF and SLAIN), Bim1 (orthologous to EB1) and Bik1 (orthologous to

CLIP-170). A multivalent web of redundant interactions links the three +TIPs together to form a ‘+TIP body’ at the end of chosen microtubules. This body behaves as a liquid condensate that

allows it to persist on both growing and shrinking microtubule ends, and to function as a mechanical coupling device between microtubules and actin cables. Our study identifies

nanometre-scale condensates as effective cellular structures and underlines the power of dissecting the web of low-affinity interactions driving liquid–liquid phase separation in order to

establish how condensation processes support cell function. SIMILAR CONTENT BEING VIEWED BY OTHERS DIFFERENTIAL REGULATION OF SINGLE MICROTUBULES AND BUNDLES BY A THREE-PROTEIN MODULE

Article 03 June 2021 REGULATION OF MICROTUBULE DYNAMICS, MECHANICS AND FUNCTION THROUGH THE GROWING TIP Article 18 August 2021 PHASE SEPARATION OF EB1 GUIDES MICROTUBULE PLUS-END DYNAMICS

Article 19 December 2022 MAIN Microtubules play a central role in moving and positioning diverse cargos within eukaryotic cells and thus in controlling cellular architecture and physiology

(reviewed in ref. 1). To fulfil these functions, individual microtubules acquire specialized behaviours to carry out dedicated roles independently of each other. One large class of

regulators contributing to microtubule specialization are microtubule plus-end tracking proteins (+TIPs), which can be broadly sorted into two groups. The first group comprises ubiquitously

expressed and evolutionary conserved proteins that bind the plus-ends of most if not all microtubules (reviewed in refs. 2,3). These include the end binding proteins (EBs, for example, EB1,

EB2 and EB3 in metazoans), which directly bind microtubule plus-ends, and the cytoplasmic linker proteins (CLIPs, for example, CLIP-170 in metazoans), which bind microtubule plus-ends

through EBs. These +TIPs typically track growing but not shrinking microtubule plus-ends. The second group of +TIPs, the recently described ‘patterning +TIPs’4, comprises protein families of

diverse phylogenetic origins that typically associate with and specify the function of individual microtubules. Representatives include the microtubule–actin crosslinking factor

(MACF/ACF7/Shot5), SLAIN motif-containing proteins 1 and 2 (ref. 6) and adenomatous polyposis coli (APC (refs. 7,8)). These +TIPs bring together plus-ends of specialized microtubules with

target cellular structures such as the actin cytoskeleton, anchorage sites at the plasma membrane, or chromosomes (reviewed in refs. 2,3). However, what restricts these patterning +TIPs to

dedicated microtubule ends is poorly understood. The budding yeast _Saccharomyces cerevisiae_ offers a powerful model for studying how microtubules become specialized. During mitosis, every

cell comprises two spindle pole bodies (SPBs, functional metazoan centrosome equivalents): an old SPB, inherited from the previous mitosis, and a newly synthesized one (reviewed in ref. 9).

Each SPB nucleates a small aster composed of one to three cytoplasmic microtubules10,11. Interestingly, these cytoplasmic microtubules are specialized in an SPB-dependent manner. The old SPB

forms long microtubules that reach to the bud cortex, the future daughter cell. In contrast, microtubules generated from the new SPB remain highly dynamic and short12,13,14,15. The cortical

interactions of old SPB microtubules orient this SPB towards the bud16,17 and align the intranuclear spindle with the future cell division axis, before anaphase onset. Spindle elongation

during anaphase then distributes the genetic material equally between mother and bud18,19,20. Microtubule specialization at the old SPB relies on exclusive decoration of their plus-ends with

the protein Kar9, a patterning +TIP. At the plus-end of one microtubule, which Kar9 binds through the EB-family member Bim1, Kar9 interacts with the CLIP-family member Bik1 and the type V

myosin Myo2, an actin-directed motor protein4,8,21,22,23. Myo2 then pulls the microtubule plus-end along actin cables to drive its specific interaction with the bud cortex24,25. A unique

feature allowing Kar9 to remain associated with a chosen microtubule throughout mitosis is its ability to track its plus-end throughout phases of both microtubule growth and shrinkage19,20.

However, the mechanisms of this behaviour are unknown. In this Article, to address the fundamental issue of microtubule specialization, we investigated the mechanisms of Kar9 cohesion and

persistence to essentially one dynamic microtubule plus-end in vivo through dissecting the interaction network that Kar9 establishes with its key partners Bim1 and Bik1. RESULTS KAR9-NETWORK

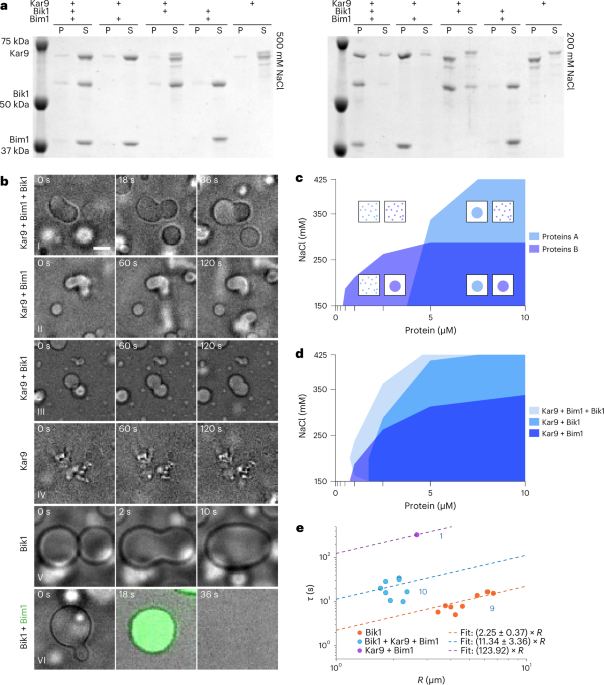

COMPONENTS UNDERGO PHASE SEPARATION IN VITRO To characterize the interactions of the Kar9-network core components with each other, we recombinantly produced and purified Kar9, Bim1 and

Bik1, and monitored their interactions in vitro using a pelleting assay. Mixed together in stoichiometric amounts (10 μM each), the three proteins were soluble in a standard,

crowding-agent-free and pH-neutral buffer containing 500 mM sodium chloride, but pelleted readily upon ultracentrifugation when the salt concentration was reduced to 200 mM (Fig. 1a). Phase

contrast microscopy and fluorescence recovery after photobleaching (FRAP) experiments indicated that under low-salt condition the proteins phase separated into liquid-like droplets in which

Kar9 and Bim1 diffuse slowly and Bik1 more rapidly (Fig. 1b, Extended Data Fig. 1 and Supplementary Movie 1). The mixtures spiked with low level of green fluorescent protein (GFP)-tagged

versions of the proteins indicated that Bik1, Bim1 and Kar9 were enriched 8, 27 and 15 times, respectively, in these droplets (Extended Data Fig. 2a). Removal of Bim1 or Bik1 changed size

and dynamic behaviour of the droplets (Fig. 1b and Supplementary Movies 2 and 3) but did not affect coalescence. Removing Kar9 fully solubilized the Bim1 + Bik1 mixture even at 200 mM salt:

although Bik1 condensed on its own in reduced salt conditions (Supplementary Movie 4), Bim1 addition resolubilized it (Supplementary Movie 5). When alone, Kar9 was soluble only at 500 mM

salt. At reduced salt, it precipitated without observed dynamics instead of condensing into liquid-like droplets (Supplementary Movie 6). Together, these data indicate that, while insoluble

on its own, Kar9 promotes liquid–liquid phase separation of Bim1 and Bik1 at reduced salt, and is itself enriched and soluble within the droplets formed. To better characterize the phase

separation behaviour of the stoichiometric Kar9 + Bim1 + Bik1 mixture, we analysed it with varying salt and protein concentrations (150–425 mM NaCl and 0.1–10 μM of each protein). Droplet

formation was screened by microscopy. The Kar9 + Bim1 + Bik1 droplets formed even at 425 mM salt (Fig. 1c,d). Without Bik1, the Kar9 + Bim1 droplets dissolved at salt concentrations above

300 mM salt. Removing Bim1 increased the Kar9 + Bik1 mixture’s critical concentration for droplet formation at most salt concentrations. At 200 mM salt, the critical protein concentration

was between 0.5 μM and 1.0 μM each for Kar9 + Bim1 + Bik1 and between 1.0 μM and 2.5 μM for both Kar9 + Bim1 and Kar9 + Bik1. Varying solely Kar9 concentration indicated that 1.0 μM was

sufficient to induce droplet formation in an equimolar mixture of 10 μM each of Bim1 and Bik1 (Extended Data Fig. 2b). Thus, even in absence of crowding, the core Kar9-network components

underwent phase separation over a broad range of sodium chloride and protein concentrations. Analysis of droplet size, morphology and dynamics within minutes from dropping the salt

concentration indicated that those formed by Bik1 alone were the most fluid, fusing and relaxing within seconds, followed by Kar9 + Bim1 + Bik1 (tens of seconds) and Kar9 + Bik1 and Kar9 +

Bim1 droplets (hundreds of seconds; Fig. 1b,e). Kar9 + Bim1 + Bik1 and especially Kar9 + Bim1 droplets became rapidly viscous; droplets joining late in the reaction formed chains faster than

they could relax to round shape (Fig. 1b). Thus, droplet composition and ageing properties widely affected their fluidity. KAR9-NETWORK FORMATION IS GOVERNED BY MULTIVALENCY INTERACTION The

data presented above indicated that Kar9, Bim1 and Bik1 must interact with themselves and each other through a multivalent network of binding interfaces. Several interactions between the

core Kar9-network components Kar9, Bim1 and Bik1 have been previously determined. As illustrated in Fig. 2a, Kar9 is composed of an N-terminal spectrin-repeat-containing domain that binds

Myo2 and mediates Kar9–Kar9 self-association4. The C-terminal domain of Kar9 is disordered and enriched with basic, serine and proline residues (Extended Data Fig. 3). It contains at least

three linear motifs (SxIP and LxxPTPh), which bind the EB homology domain (EBH) of Bim1 (refs. 4,8,26,27). Bim1 contains a microtubule-binding calponin homology (CH) domain that is connected

to a dimerizing coiled coil and EBH domain by a basic- and serine-rich disordered linker28 (Extended Data Fig. 3). The disordered C-terminal tail of Bim1 is acidic and terminates in an

EEY/F motif that binds the cytoskeleton-associated protein-glycine-rich (CAP-Gly) domain of Bik1 (refs. 29,30). In Bik1, the N-terminal CAP-Gly domain is connected to a dimerizing coiled

coil domain by a basic- and serine-rich, disordered linker31 (Extended Data Fig. 3). Its C-terminal portion contains a zinc-finger (ZnF) domain and a short, EEY/F-like motif. Interestingly,

the homologues of Bim1 and Bik1 in mammals and fission yeast, that is, EB1 and CLIP-170, and Mal3 and Tip1, respectively, are found to also undergo phase separation in vitro and in

vivo32,33,34 (co-submitted with this manuscript). As Bik1 also undergoes phase separation on its own (Fig. 1b, ref. 35), it must contain additional self-association interfaces besides the

coiled-coil that are currently not known. Notably, the C-terminal domain of Kar9 also carries at least one binding site for Bik1 (ref. 23), consistent with Kar9 phase separating together

with Bik1 (Fig. 1b). Since Kar9 is a strong driver of Kar9-network condensation (Fig. 1a,b and Extended Data Fig. 2b), we reasoned that it must contribute substantially to multivalency.

Strikingly, the disordered C-terminal domain of Kar9 alone did not promote phase separation of Bim1 and Bik1 as much as full-length Kar9 (Fig. 2b). Therefore, and given its role in

self-association, we investigated whether its N-terminal domain was important for multivalency and phase separation of the network. The crystal structure of the Kar9 N-terminal domain from

the budding yeast _Naumovozyma castellii_ (NcKar9N) revealed three crystallographic dimers with total buried surface area per protomer of 1,549, 1,177 and 851 Å2, respectively4. The

interfaces forming these dimers are referred to as α, β and γ (Fig. 2c). While the α- and β-dimer interfaces make two symmetric contact points, the γ interface is established by a single one

(Extended Data Fig. 4a–c). Remarkably, the residues forming the three interfaces (Methods) are well conserved across Kar9 orthologues (Extended Data Fig. 5). To test whether any of the

three self-association interfaces could mediate NcKar9N–NcKar9N interactions in vitro, we performed a mutagenesis study with His-tagged NcKar9N. To this end, we mutated two conserved

residues in each of the interfaces to alanine (Fig. 2c and Extended Data Figs. 4a–c and 5). The integrity of the three mutants was confirmed by circular dichroism (CD) spectroscopy, which

revealed spectra and cooperative thermal unfolding profiles similar to those obtained for the wild-type protein (Extended Data Fig. 4d,e). The oligomerization state of the different NcKar9N

variants was then assessed by size exclusion chromatography followed by multi-angle light scattering (SEC–MALS). Consistent with our previous results4, analysis of wild-type NcKar9N (200 μM

protein injected onto the size exclusion chromatography column) at 150 mM sodium chloride yielded molecular masses consistent with the presence of dimers (118 kDa; calculated molecular mass

of wild-type His-NcKar9N monomer is 50 kDa; Fig. 2d). At 50 mM salt, a broader elution profile was obtained, shifted towards a lower elution volume. The measured molecular mass increased to

a value much higher than 200 kDa, suggesting the formation of non-stoichiometric oligomers (Fig. 2e). In both salt conditions, mutating the α-interface (NcKar9N-α−) resolved these multimers

to monomers (52 kDa). The β-interface mutation (NcKar9N-β−) did not affect dimer formation at 150 mM salt but reduced the larger oligomers formed at 50 mM salt towards a molecular mass of a

dimer (97 kDa). The γ-interface mutant (NcKar9N-γ−) reached a mass of 107 kDa at 150 mM salt and 180 kDa at 50 mM, consistent with limiting the formation of oligomers up to tetramers. These

observations indicate that all three crystallographic contact sites of Kar9N mediate NcKar9N–NcKar9N interactions of different strengths in solution, with the α-interface mediating the most

stable interaction. KAR9 SELF-ASSOCIATION DRIVES PHASE SEPARATION OF THE KAR9 NETWORK We next reasoned that the interactions of Kar9 with itself, as well as with Bim1 and Bik1 (Fig. 2a),

probably drives phase separation of the Kar9 network in vitro. Furthermore, they should contribute cooperatively to this phenomenon. Therefore, mutating interaction sites individually may

have some effect on the ability of the network to undergo phase separation. Accumulating such mutations should additively impair coalescence of network components. To test this idea, we

inferred in _S. cerevisiae_ Kar9 the self-association sites identified in NcKar9 on the basis of sequence conservation (Extended Data Fig. 5) and mutated them individually or in combination.

We then investigated whether this affected the phase separation behaviour of the Kar9 network. Interfering with any of the Kar9 self-association sites individually had some effect on the

ability of the mutant protein to promote phase separation of the network (Fig. 3a): the corresponding phase diagrams deviated from that of wild-type Kar9 at 1.0 μM protein and at >300 mM

sodium chloride concentrations. Among the three Kar9 self-association interface mutants, Kar9-γ− had the strongest effect at >300 mM salt and at high protein concentration (10 μM),

followed by Kar9-α−. At <200 mM salt and lower protein concentrations (1 μM), Kar9-α− showed the strongest effect. The Kar9-β− mutant behaved very similarly to wild-type Kar9, except that

it did not promote phase separation at lower protein concentration (1.0 µM). Mutating the three interfaces together enhanced these effects, although the mutant protein Kar9-αβγ− still

promoted phase separation of the protein mixture over a reduced but still broad range of concentrations and salinity (Fig. 3a,b). Strikingly, for each of these variants, Bik1 removal

strongly reduced their ability to promote phase separation. The Bim1 + Kar9-αβγ− mixture showed the strongest defect in coalescence (Fig. 3a,c). Thus, Bik1 and the three Kar9

self-association interfaces contribute all cooperatively to the phase separation behaviour of the core Kar9-network components. As strong defects were observed only when combining Kar9

interface mutations and removing Bik1, we concluded that the different homo- and heterotypic interactions between Kar9 and Bik1 act redundantly in coalescence and that we identified a

sufficient number of interfaces to already substantially perturb the process in vitro. Testing the role of the self-association interfaces of Kar9 in absence of Bim1 proved not feasible

because the mutant forms of Kar9 became rapidly insoluble in absence of Bim1. Kar9 interacts with low nanomolar affinity with Bim1 (refs. 8,36), suggesting that it is always associated with

Bim1 in living cells. Thus, for simplicity the two proteins are considered as an obligate single unit for the rest of this study, a notion that is consistent with the fact that Kar9 does not

localize to microtubules in absence of Bim1 (refs. 21,22). KAR9-NETWORK MULTIVALENCY FACILITATES SPINDLE POSITIONING IN VIVO Next, we investigated whether the identified interfaces

contribute to Kar9-network function in vivo. We constructed mutant yeast strains where the endogenous _KAR9_ gene was replaced with alleles abrogating each Kar9 self-association interface

alone, in combinations of two, or all three together, in presence or absence of Bik1. As Kar9 function becomes essential for growth in cells lacking the dynein gene _DYN1_ (ref. 37), each

_K__A__R__9_ allele was combined with the _dyn1Δ_ mutation to assay their functionality. As beyond its role in the Kar9 network Bik1 is also essential for dynein function37,38, we did not

need to remove the _DYN1_ gene in the _bik1Δ_ mutant cells to assay Kar9 functionality. As shown in Fig. 4a and Extended Data Fig. 6, the _kar9-αβγ__−_ triple interface mutant allele was

lethal or nearly so in combination with _bik1Δ_ at all tested temperatures (25–35 °C); in these cells the Kar9 network was not functional. Mutating any of the α, β or γ interfaces alone, or

removing Bik1 individually, however, did not cause much of a phenotype at any of these temperatures, even when _DYN1_ was deleted (Fig. 4a and Extended Data Fig. 6). Likewise, any

combination of two of these mutations failed to cause a much detectable phenotype, except when the α interface and Bik1 were both absent, which affected cell growth at high temperature. We

conclude that all three Kar9 self-interaction interfaces are functional in vivo, and that they work cooperatively with each other and Bik1. To characterize how the progressive reduction of

multivalency in the Kar9 network affected cell viability, we investigated the effects of cumulating mutations on spindle alignment and positioning (Fig. 4b,c). While _bik1Δ_ and Kar9

triple-interface mutations separately had no or little effect on the outcome of mitosis at 25 °C, their combination caused the accumulation of late-anaphase cells with elongated spindles

that remained in the mother cell and failed to segregate an SPB to the bud. Furthermore, two-thirds of the late-anaphase _kar9-αβγ__−_ _bik1Δ_ double-mutant cells mispositioned their

spindles. Accordingly, up to 17% of these mutant cells contained more than one spindle during mitosis, a phenotype that is essentially never observed in wild-type cells (Fig. 4d).

MULTIVALENCY UNDERLIES KAR9 RESTRICTION TO FEW MICROTUBULES IN VIVO Thus, we next investigated whether multivalency contributes to Kar9 protein localization in vivo. At 25 °C, cells

expressing wild-type or Kar9 mutant proteins tagged with the fluorescent protein mNeonGreen revealed that mutating the γ interface had little effect, but erasing the α or β interface

individually reduced pre-anaphase Kar9 levels at microtubule plus-ends by 40% and 20%, respectively (Fig. 5a). Simultaneously mutating an increasing number of Kar9 self-association

interfaces further decreased Kar9 levels at microtubule ends. Abrogating all three interfaces reduced these levels by 60% and by 70% when Bik1 was removed as well. Strikingly, the Kar9-αβγ−

protein failed to remain focused on the tip of a single microtubule. Rather, this mutant protein distributed more symmetrically to microtubules on both sides of the spindle compared with its

wild-type counterpart (asymmetry index of 0.75 and 0.9, respectively; Fig. 5b). This phenotype was enhanced upon _BIK1_ deletion (0.42 in the _kar9-αβγ__−_ _bik1Δ_ double-mutant cells; Fig.

5b). In these cells, the reduced Kar9 levels at microtubule plus-ends were not only due to the redistribution of the protein to several microtubules since the total protein amount

localizing to microtubules was still very low compared with wild-type and single-mutant cells (Extended Data Fig. 7). MULTIVALENCY ENABLES KAR9 TO TRACK SHRINKING MICROTUBULE ENDS The Kar9

network possesses the unique ability to track both growing and shrinking microtubule plus-ends19,20. We reasoned that multivalency might support this process by increasing the avidity of the

Kar9 network for microtubule tips. Thus, we imaged the wild-type and Kar9-αβγ− mutant proteins tagged with mNeonGreen at high spatial and temporal resolution. As previously shown20, the

punctum formed by wild-type Kar9 tracked the plus-end of its target microtubule throughout its growth and shrinkage cycles (Fig. 5c,d and Supplementary Movie 7). Other Kar9 puncta formed

occasionally on tips of other microtubules but rapidly disappeared either by fusing with the main punctum or by fading away in the cytoplasm. This persistent tracking of growing and

shrinking microtubule plus-ends by Kar9 was occasionally lost in the _kar9-αβγ__−_ and _bik1Δ_ single-mutant cells (Fig. 5d,e and Supplementary Movie 8). This phenotype was synergistically

enhanced in the _kar9-αβγ__−_ _bik1Δ_ double-mutant cells: nearly 50% of them lost their main Kar9 punctum within 3 min of imaging (9% in wild type; Fig. 5d,e). Puncta tended to then

re-assemble next to SPBs and track the next emerging microtubule plus-end. Punctum disappearance generally happened at what seemed to be the end of a microtubule growth phase or shortly

after microtubule shrinkage started. To quantitatively analyse whether Kar9 localization depends on microtubule length changes, we automatically identified microtubule growth and shrinkage

phases (Extended Data Fig. 8a; for details, see Methods). Rates estimated from individual phases suggested distinctions between wild type and mutants (Extended Data Fig. 8b,c), but they were

not directly comparable because durations of shrinkage phases differed significantly between strains (Extended Data Fig. 8d). We therefore estimated linear mixed effects models jointly for

the strains, because they capture the behaviour of an ‘average’ microtubule, as well as variability between microtubules (Methods). This analysis indicated that microtubule growth and

shrinkage rates did not differ between strains (Fig. 5g; note significantly different initial lengths due to different phase durations and thereby overall dynamics, Extended Data Fig. 8e).

In fitting with the loss of Kar9 puncta reported above, in the _kar9-αβγ__−_ _bik1Δ_ double-mutant cells the average intensity of the Kar9 punctum decreased during microtubule shrinkage,

unlike in wild-type cells where it rather increased (Fig. 5f and Extended Data Fig. 8c). Again, this behaviour was not observed nearly as clearly in cells carrying either _bik1Δ_ or Kar9

triple interface mutations alone. KAR9 STRUCTURES AT MICROTUBULE ENDS ARE NON-STOICHIOMETRIC As Kar9 function in vivo (Figs. 4 and 5) correlates extremely well with Kar9 ability to promote

condensation of the network components in vitro (Figs. 1–3), we hypothesized that the network proteins might function together by forming a condensate at the tip of target microtubules in

vivo. However, in vivo Kar9 puncta are smaller than the diffraction-limited resolution of light microscopy, preventing the visualization of their morphology and direct assay of their

material properties. Instead, we investigated whether they showed other hallmark properties of biomolecular condensates. One such property consists of their ability to vary in size as the

amount of available material changes (reviewed in ref. 39). Thus, we asked whether Kar9 puncta showed such behaviour in vivo. Quantification of the fluorescence of the Kar9-mNeonGreen puncta

showed that they widely varied in intensity as cells progressed from G1 to metaphase, upon insertion of a second copy of the gene in the genome, or when overexpressed (Fig. 6a–c).

Abrogating all three Kar9 self-association interfaces extensively reduced puncta intensity upon overexpression (Fig. 6b,c), as for the endogenous protein (Fig. 5a). In contrast, the Dam1

protein, which forms a stoichiometric complex at the tip of kinetochore microtubules40,41, formed puncta of constant fluorescence intensity when tagged with mNeonGreen, irrespective of cell

cycle stage or Dam1 expression levels (Fig. 6a,b). Thus, unlike Dam1, the Kar9 body is not a stoichiometric structure, but a condensed, cohesive structure. Dam1 is estimated to be present in

17 copies per kinetochore microtubule40. Using its intensity as a reference, we estimate that metaphase cells recruit, on average, at least 70 Kar9 molecules at the tip of a single

microtubule. KAR9 SHOWS A LIQUID-LIKE BEHAVIOUR ON ASTRAL MICROTUBULE ENDS As mentioned earlier, in cells containing several Kar9 puncta, these frequently merged with each other (Fig. 7a,b

and Supplementary Movie 9) and stably remained together for many subsequent timeframes, suggesting that they had truly fused into a single entity. In wild-type cells, such fusion events took

place every 2.6 min on average, whereas fission events were two-fold less frequent (Fig. 7b), as expected given the fact that droplet fusion is energetically more favourable than fission.

Decreasing the multivalency of the system increased both rates and reduced their relative ratio. These observations suggest that the Kar9 network functions as a liquid-like condensate in

vivo. Hexanediol resolubilizes certain liquid–liquid phase separated proteins both in vitro and in vivo by disturbing low-affinity, hydrophobic interactions, but leaves aggregates and

stoichiometric complexes relying on high-affinity interactions mostly intact42. In vitro, phase separation of equimolar mixtures of Kar9 + Bim1 + Bik1 droplets was indeed severely affected

by addition of 5% hexanediol, especially at intermediate sodium chloride concentrations (>250 mM; Fig. 7c). Thus, we tested whether Kar9 puncta intensity was also sensitive to hexanediol

in vivo. Imaging pre-anaphase cells immediately after resuspending them in medium containing 5% hexanediol reduced puncta intensity about eight-fold (Fig. 7d,e). Both mNeonGreen-Bim1 and

mNeonGreen-Bik1 intensities at astral microtubule tips were similarly affected (Fig. 7e and Extended Data Fig. 9a). Hexanediol did not act indirectly by depolymerizing astral microtubules

since the treatment had only a mild effect on them, as determined using GFP-Tub1 as a reporter (Extended Data Fig. 9b,c). Furthermore, eliminating all astral microtubules using nocodazole

did not severely affect the intensity of Kar9-mNeonGreen puncta that re-localized close to SPBs in these cells (Extended Data Fig. 9d,e). Thus, we concluded that hexanediol potently and

rapidly inhibited the liquid–liquid phase separation of the Kar9-network components to similar extents in vitro and in vivo. DISCUSSION A wide range of biomolecules use low-affinity,

multivalent interactions to undergo liquid–liquid phase separation and generate membrane-less organelles (reviewed in refs. 39,43). Here we show that a dense web of redundant interactions

links the core components of the Kar9 network together to assemble a nanometre-scale structure, which we name ‘+TIP body’, at the plus-end of essentially one single cytoplasmic microtubule

in yeast. Our data suggest that this body is a liquid-like condensate, its dynamic and microtubule-binding properties allowing it to persist and track both the growing and shrinking plus-end

of its target microtubule. We postulate that the material properties of the nanometre scale Kar9 +TIP body supports its function as a ‘mechanical coupling device’ that supports the transfer

of forces between the actin and the microtubule cytoskeleton to properly position the mitotic spindle during cell division. Several lines of evidence support our hypothesis. Firstly, phase

separation in vitro relies on multiple high-, medium- and low-affinity interactions within the Kar9 network. The identified interfaces (Kar9–Kar9 (ref. 4 and this study) and Kar9–Bim1 (refs.

8,36)) are all conserved across Kar9 homologues and are therefore all functionally relevant. Accordingly, these interaction interfaces are instrumental for proper function of the Kar9

network. Furthermore, their redundancy in vivo perfectly parallels their cooperativity for network phase separation in vitro. Secondly, the Kar9 +TIP body forms a non-stoichiometric

assembly, able to undergo fission and fusion, supporting the idea that it is a liquid-like structure within the cell. Finally, the proper function of this assembly does not depend on the

exact amount of Kar9 protein present at the microtubule tip. Indeed, the substantial reduction of Kar9 levels caused by most single and double mutations of the self-association interfaces

does not translate into noticeable functional defects. Thus, our data indicate that the Kar9 network undergoes condensation in cells and that this property is instrumental to fulfil its

cellular function. Considering that the phenotypic consequences of decreasing multivalency in the system indicates which of the body’s functionalities are specifically dependent on phase

separation, our data provide compelling support for condensation mediating at least two key functional properties of the network. Firstly, condensation underlies recruitment and

concentration of Kar9 to a selected microtubule plus-end in cells. Kar9 has a high affinity for Bim1, and Bim1 for the plus-ends of growing microtubules8,26. Thus, its recruitment to

microtubule plus-ends via Bim1 must locally enhance Kar9 concentration and may nucleate condensation, leading to recruitment of more Kar9 and its partners. Ostwald ripening of this

condensate, that is, the tendency of the biggest condensate to collect all the available material, could explain why budding yeast cells form virtually only one Kar9 +TIP body20. Thus,

condensation offers a determining mechanism to specialize the underlying microtubule. Secondly, multivalency underlies the remarkable capacity of the Kar9 +TIP body to track shrinking

microtubule ends. As condensation proceeds, accruing Kar9 levels should bring an excess of Bim1 molecules with itself, allowing Bim1 binding to low-affinity sites on the microtubule

lattice44. Supporting this notion, we found that overexpression of Kar9 tends to extend the +TIP body along the microtubule lattice (Fig. 6c). We suggest that such lattice ‘wetting’ supports

both persistence of the +TIP body on shrinking microtubule plus-ends (Fig. 7f), as well as its cohesion to the dynamic microtubule plus-end necessary to support the transmission of pulling

forces generated either by microtubule shrinkage or by directional movement of myosin motors along actin cables. Thereby, condensation facilitates the function of the +TIP body in

mechanically linking microtubules and actin cables to mediate nuclear positioning. The hypothesis of a liquid-like Kar9 +TIP body is especially attractive because it helps explaining

cellular observations that remained difficult to rationalize so far, such as Kar9’s unique localization pattern and its remarkable role in ‘gluing’ together two highly dynamic intracellular

structures, namely microtubule tips and actin cables. Similar mechanisms may also explain how other patterning +TIPs, such as APC and MACF, target, persist and specialize the dynamics and

functions of specific subclasses of microtubules in other cell types. Importantly, three recent studies by Miesch et al.32, Song et al.34 and Maan et al.33 strongly support our overall

conclusion that +TIPs can form nanometre-scale phase-separated bodies around microtubule ends. Investigating further the condensate properties of +TIP bodies may thus change our current view

and understanding of how +TIPs accumulate to selected microtubule plus-ends, functionally specialize them, control their dynamics and regulate their interactions with different cellular

targets. METHODS CLONING AND PROTEIN PREPARATION PLASMID PREPARATION Expression vectors were produced either by homologous recombination with polymerase chain reaction (PCR)-amplified or

synthetic genes and amplified backbones or site-directed mutagenesis (QuikChange, Agilent). The wild type4 and mutant N-terminally hexa-histidine-tagged _N. castelli_ Kar9 N-terminal domain

(NcKar9N, residues 1–410) were cloned into the pET-based expression vector PSPCm2 (ref. 45). The interface mutations in _N. castellii_ Kar9 (UniProt ID G0VE12) were created by QuikChange and

are as follows: α, Phe288Ala/Phe344Ala; β, Arg233Ala/Ile237Ala; γ, Tyr363Ala/Arg364Ala. Full-length wild-type8 and mutant and Kar9C (405–644) N-terminally hexa-histidine-tagged _S.

cerevisiae_ Kar9 (UniProt ID P32526) were cloned into the Acembl vector pACE46. The interface mutations in _S. cerevisiae_ Kar9 were created in yeast (see below) and then cloned into pACE.

They are as follows: α, Phe292Ala/Leu347Ala; β, Arg237Ala/Asn241Ala; γ, Tyr366Ala/Arg367Ala. Full-length _S. cerevisiae_ wild-type and N-terminally hexa-histidine-tagged _S. cerevisiae_ Bim1

(ref. 8) (UniProt ID P40013), and _S. cerevisiae_ Bik1 (UniProt ID P11709) were cloned into pET3d (Invitrogen) and PSTCm1 (ref. 45), respectively. All primers are listed in Supplementary

Table 1. PROTEIN EXPRESSION AND PURIFICATION Sequence verified plasmids were transformed into BL21(DE3) _E. coli_ cells for protein expression. To produce the proteins, liquid cultures were

shaken in LB medium containing the appropriate antibiotic until an optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of 0.6 was reached. Expression was induced by the addition of 0.75 mM

isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactoside. Induced cells were further incubated overnight at 20 °C. Cells were lysed using the sonication method or high-pressure homogenizers (Avestin Emulsiflex-C3 High

Pressure Homogenizer or Microfluidics Microfluidizer) in 20 mM Tris–HCl (pH 7.5), supplemented with 800 mM (full-length Kar9 alone8) or 500 mM (all other proteins) NaCl. Cell debris was

removed by centrifugation. Cleared cell lysates were filtered using a 0.45 μm filter. Affinity purification of His-tagged proteins was carried out at 4 °C by immobilized metal affinity

chromatography on Ni2+-Sepharose columns (Cytiva) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. For NcKar9N wild-type and full-length Kar9 (purified without Bim1), the hexa-histidine tag was

enzymatically cleaved with PreScission and TEV protease, respectively. All protein samples were further applied on a pre-equilibrated Superdex-75 or −200 size exclusion chromatography

column (Cytiva). For the production of different Kar9-Bim1 complex variants, wild-type or mutant hexa-histidine-tagged Kar9 and untagged Bim1 were separately expressed in bacteria and mixed

before lysis in 500 mM NaCl. The purity of recombinant proteins was confirmed by Coomassie-stained SDS–PAGE, and the identities of the proteins were assessed by mass spectral analyses.

Despite substantial efforts, we were unsuccessful in purifying full-length Kar9 oligomerization interface mutants in absence of Bim1. Purification of full-length Kar9 without Bim1 was also

challenging in case of wild-type protein. Most likely, in absence of Bim1 the hydrophobic SxIP and LxxPTPh Bim1 binding motifs unspecifically stick to other parts of Kar9 or cellular debris

during purification, leading to low yield. We can only speculate, why Kar9–Kar9 oligomerization interface mutations made the situation even worse. Potentially, even more sticky patches were

exposed in absence of oligomerization, reducing overall solubility even further. IN VITRO PHASE SEPARATION ASSAYS PELLETING ASSAY Protein stocks were mixed and diluted in 1.5 ml test tubes

with 20 mM Tris–HCl, pH 7.5, supplemented with 500 mM NaCl to reach a protein concentration of 40 μM each in 5 μl total volume at 500 mM NaCl (722 mM for Kar9 and Kar9 + Bik1). Next, 15 μl

of low (100 mM or 26 mM for Kar9 and Kar9 + Bik1) or high-salt (500 mM or 426 mM for Kar9 and Kar9 + Bik1) Tris buffer was added to dilute the samples 4:1 to reach a final concentration of

10 μM in 200 or 500 mM NaCl, respectively. The mixtures were then incubated in a thermomixer for 30 min at 25 °C while gently shaking. After 10 min spinning at 16,900_g_ and 25 °C, the

supernatant was transferred into a separate tube. The invisible pellets were resuspended in 20 μl of the Tris buffer (containing either 200 or 500 mM NaCl). Samples were analysed by

Coomassie-stained 10% SDS–PAGE. STATIC LIGHT-MICROSCOPY ASSAY FOR THE ASSEMBLY OF PHASE DIAGRAMS A dilution series of either 5× (wild-type proteins) or 4× (mutant proteins and Kar9 + Bik1,

due to concentration limitations) protein mixtures as above was prepared at high salt (usually 500 mM, except experiments with Kar9 purified alone 718 mM) to reach a broad range of protein

concentrations (usually 0.1–10 μM final concentrations after dilution, thus either 0.5–50 or 0.4–40 μM before dilution). The reservoir wells of an MRC2 crystallization plate (Swissci) were

then filled with buffers matching the final salt concentration of 150–425 mM NaCl. Next, the protein stock solutions were dispensed into the MRC2 plate’s drop wells and diluted 5:1 or 4:1

(depending on the protein stock concentration) in a total volume of 1 μl using a Mosquito pipetting robot (SPT Labtech) with dilution buffers provided in a different plate to reach salt

concentrations matching the reservoir wells. After 30 min incubation, all wells were imaged by phase contrast microscopy. The phase separation state of each well is reported in the source

data for the phase diagrams shown in Figs. 1, 2, 3 and 7 and Extended Data Fig. 2. An approximate binodal line was constructed between phase-separated and soluble conditions (through the

middle points at each tested protein concentration). TIME-RESOLVED MICROSCOPY ASSAY Either 5× or 4× protein mixtures were prepared and then diluted to 10 μM and 220 mM NaCl in a Nunc Lab-Tek

II chambered eight-well coverglass. To verify enrichment of His-tagged protein in droplets, Atto-488-NTA was used at 1 μg ml−1 concentration. Samples were imaged on a DeltaVision Personal

microscope (Cytiva) at 60× or 100× magnification using transmission and FITC channels in a single plane close to the coverglass surface. DROPLET FUSION ANALYSIS In the inset of the Extended

Data Fig. 10, a typical fusion event of Bik1 is shown. To measure the fusion time _τ_, we assume that a uni-axially deformed droplet relaxes to its final spherical state. Parameter \(=

\frac{{L - W}}{{L + W}}\), was used to calculate the fusion time _τ_. _L_ is the major axis of the deformed droplet, and _W_ is the minor axis. Fitting an exponential curve to the

time-dependent parameter _A_ would give the fusion time _τ_ (Extended Data Fig. 10). _τ_ has relationship with viscosity and surface tension via Navier–Stokes equation: $$\tau =

\frac{{\left( {2\lambda + 3} \right)\left( {19\lambda + 169} \right.}}{{40(\lambda + 1)}}\frac{{\eta _{{\mathrm{ext}}}R}}{\gamma }$$ (1) where \(\lambda = \eta _{{\mathrm{int}}}/\eta

_{{\mathrm{ext}}}\) is the ratio of internal and the external viscosities, _R_ is the final radius of the droplet in spherical state and _γ_ is the surface tension. In the case that

\(\lambda \ll 1(\eta _{{\mathrm{int}}} \ll \eta _{{\mathrm{ext}}})\), one can simplify the equation to: $$\tau = \frac{{19}}{{20}}\frac{{\eta _{{\mathrm{int}}}R}}{\gamma }$$ (2) which is

valid where the viscosity of the protein condensed phase (_η_int) is much higher than the viscosity of the protein dilute phase (_η_ext). For instance, viscosity of the Bik1 droplet phase

has been reported previously as \(\eta _{{\mathrm{int}}} \approx 18.2\left( {Pa \cdot s} \right)\) which is four orders of magnitude higher than the Bik1 dilute phase35. In Fig. 1e,

\(\frac{\tau }{R} = \frac{{19}}{{20}}\frac{{\eta _{{\mathrm{int}}}}}{R}\) (equation (2)) the slope is measured from fitting the data linearly. The value of \(\frac{\tau }{R}\) for Bik1 is

measured as \(2.25 \pm 0.37\left( {s/m} \right)\), which is consistent with the previously reported values of viscosity and surface tension for Bik1, \(18.2\left( {Pa \cdot s} \right)\) and

7 (μN m−1), respectively35. However, higher values of \(\frac{\tau }{R}\) for Bik1 + Kar9 + Bim1 and Kar9 + Bim1, 11.34 ± 3.46 and \(123.92\left( {s/m} \right)\), suggests much slower fusion

for these systems. Unfortunately, owing to the slow fusion speed and the comparatively fast chain formation, we could resolve only one isolated two-droplet fusion event. Therefore, there is

no meaningful error reported for this event47,48. DROPLET PARTITIONING AND FRAP Samples were prepared as for time-resolved microscopy above but at only 5 μM protein concentration (to reduce

number of formed droplets) and without Atto-488-NTA. Ten-fold less concentrated mNeonGreen-Bik1, Kar9-GFP or Bim1-GFP were added to the mixture of unlabelled proteins to study the dynamics

of all three components separately. Fluorescence images (partitioning) and movies (FRAP) were acquired with a Visitron Spinning Disk microscope in a single confocal slice in GFP channel

close to the bottom of the well with 1 s time intervals. For FRAP, droplets were fully bleached by a laser pulse after timeframe 5 and recovery was observed for 3 min. For partition

coefficient calculation, background (unlabelled protein mixture)-subtracted integrated densities were determined inside and outside droplets using Fiji and the inside/outside ratio was

calculated. For FRAP quantification, background-subtracted integrated densities were determined using Fiji. For Bik1 droplets, bleaching/defocus was corrected by dividing by the average

normalized intensity of nearby reference droplets. BIOPHYSICAL CHARACTERIZATION SEC–MALS experiments were performed in 20 mM Tris–HCl, pH 7.5, supplemented with 150 or 50 mM NaCl, 1 mM

dithiothreitol using a S-200 10/300 analytical size exclusion chromatography column (GE Healthcare) connected in-line to mini-DAWN TREOS light scattering and Optilab T-rEX refractive index

detectors (Wyatt Technology). Thirty microlitres of His-NcKar9N protein variants at a concentration of 200 μM were injected for each run onto the size exclusion chromatography column. CD

spectra of His-NcKar9N protein samples were recorded at 5 °C and at a protein concentration of 0.2 mg ml−1 in 20 mM Tris–HCl, pH 7.5, supplemented with 500 mM NaCl and 1 mM dithiothreitol

using a Chirascan spectropolarimeter (Applied Photophysics) and a cuvette of 0.1 cm path length. Thermal unfolding profiles between 5 °C and 80 °C were recorded by increasing the temperature

at a ramping rate of 1 °C min−1 monitoring the CD signal at 222 nm. Midpoints of thermal unfolding profiles were determined using the Global3 program (Applied Photophysics). STRUCTURAL

ANALYSIS OF CRYSTALLOGRAPHIC NCKAR9N HOMODIMER INTERFACES The three crystallographic NcKar9N homodimer interfaces were analysed using the PDBePISA server49 on Protein Data Bank (PDB) ID

7AG9. The following residues form the three different interfaces: α, F181, Q184, E185, F188, F288, E292, E299, and K303, and Y318′, E322′, K329′, R343′, F344′, Q347′, K350′ and K351′; β,

L107, E111, D123, F124, L127 and I131, and K179′, R233′, K234′, L236′, I237′ and R240′; γ, N360, Y363, R364, E367, R390 and L398, and N211′, N212′, Y363′, R364′ and L377′. The prime

discriminates the second protomer of a respective crystallographic dimer. Figures were prepared using the software PyMOL (The PyMOL Molecular Graphics System, Schrödinger, LLC). YEAST

STRAINS AND CLONING Yeast strains used in this study were created by transformation of PCR-amplified fragments that integrated into the genome by homologous recombination or crossing,

sporulation and tetrad dissection. Notably, for the creation of Kar9 interface mutations, mutant primers were used to PCR amplify the _KAR9_ open reading frame (ORF) as multiple fragments

overlapping at the sites of the point mutations. Co-transformation of the mutant fragments into a _kar9Δ_ strain yielded the full mutant ORF4. N-terminal mNeonGreen tags on Bim1 and Bik1

were introduced by transformation of the wild-type allele with PCR-amplified fragments with homology up- and downstream of the start codon to insert the tag and a selectable marker flanked

by loxP sites. Expression of Cre recombinase from a transiently introduced plasmid was used to excise the marker after selection. For expression of a second genomic copy of Dam1- or

Kar9-mNeonGreen, these ORFs were first cloned into an integrative plasmid, which was then linearized and integrated at the _URA3_ locus. Transformants were verified by PCR and sequencing,

and spores by replication onto relevant selection plates. All yeast strains and primers are summarized in Supplementary Table 1. YEAST VIABILITY ASSAY Haploid yeast strains of the given

genotypes were spotted in 10× serial dilutions, starting from OD600 0.05, by spotting 4 μl from the individual dilutions on YPD plates and incubating them at the indicated temperatures for

2–3 days. YEAST LIVE-CELL TIME-LAPSE FLUORESCENT MICROSCOPY For live-cell time-lapse fluorescent microscopy, yeast strains were exponentially grown in synthetic medium lacking tryptophan at

25 °C, collected by centrifugation at 600_g_ for 1.5 min, and placed on glass slides for imaging at 25 °C. For the phenotypes late-anaphase spindle alignment (Fig. 4c), spindle accumulation

(Fig. 4d), Kar9 fluorescence intensity (Fig. 5a) and Kar9 asymmetry (Fig. 5b), cells were imaged on a Personal DeltaVision microscope (Cytiva) at 100× magnification with 2 × 2 binning (pixel

size 128 nm) in CFP and FITC channels (_kar9Δ_ only CFP) over ten iterations separated by 13 s in 17 _z_-slices separated by 0.3 μm. For microtubule plus-end tracking (Figs. 5c–g and 7a,b),

cells were imaged on a Visitron Spinning Disk microscope used in wide field mode at 150× magnification (100× objective with 1.5× auxiliary magnification) and 2 × 2 binning (pixel size 173

nm) with simultaneous acquisition in mCherry and GFP channels over 50 iterations separated by 3.5 s in 17 _z_-slices separated by 0.3 μm. For hexanediol/nocodazole treatment, cells were

grown on YPD agar plates at low density and then resuspended in synthetic medium lacking tryptophan supplemented with 10 μg ml−1 digitonin and with 5% (w/v) 1,6-hexanediol, 30 μg ml−1

nocodazole or none of them. Imaging was performed as described above with a DeltaVision Personal microscope. MICROSCOPY DATA ANALYSIS For late-anaphase spindle alignment and spindle

accumulation, the seven most in-focus planes of the _z_-stack were sum projected and the phenotypes were manually classified in the second timeframe. The other timeframes were used to assign

cells to the analysed cell cycle stage. Cells were considered to be in late anaphase if the spindle reached at least the approximate length of the mother compartment. For Kar9-mNeonGreen

fluorescence intensity quantification, the complete _z_-stacks of timeframes 2–10 were maximum projected in Fiji50 and the background (slide)-subtracted maximum intensity for each metaphase

cell was measured and averaged over the nine timeframes. For mNeonGreen-Bim1 and -Bik1, the fluorescence at SPBs or within the spindle was excluded. For Kar9 asymmetry and cumulative

fluorescence intensity, background (cell)-subtracted intensities (integrated densities) were measured on both sides of the spindle in timeframe 2. Cumulative fluorescence intensity was

calculated as the sum of intensities on both sides. The Kar9 asymmetry index was calculated as the absolute difference divided by the sum of intensities on opposite ends of the spindle

\(\left( {\frac{{\left| {I_{{\mathrm{bud}}} - I_{{\mathrm{mother}}}} \right|}}{{I_{{\mathrm{bud}}} + I_{{\mathrm{mother}}}}}} \right)\). For microtubule plus-end tracking analysis, the

complete _z_-stacks of all 50 timeframes were maximum projected. Kar9 punctum loss (Fig. 5e) was classified manually for these movies. Further, for each Kar9 punctum the associated SPB was

determined by looking at the trajectory of Kar9 fluorescence. The 2D distance between the Kar9-mNeonGreen punctum and the relevant Spc42-mCherry focus (microtubule length) as well as the

background-subtracted (cell background) integrated fluorescence intensity was measured for each timeframe. Smoothed (moving average over three timeframes) microtubule length trajectories are

shown in Fig. 5d. Periods of microtubule growth and shrinkage were annotated automatically on non-smoothed trajectories. For each Kar9 punctum, the procedure involved: (1) applying a

Savitzky–Golay finite impulse response smoothing filter (polynomial order 1, frame length 5) to the microtubule length trajectory; (2) identifying change points in the filtered data (maximum

of five change points per trajectory, comparison with least squares linear fit, minimal distance between change points of five frames); (3) detecting minima/maxima in the unfiltered

trajectories closest to the identified change points (minimum required peak prominence of 25% of the difference between maximal and minimal microtubule length); and (4) annotating periods as

growth (shrinkage) when slopes of linear regressions on the partial trajectories between maxima/minima (or change points) were significantly positive (negative) based on _t_-tests on

coefficients of linear regressions, with _α_ = 0.05. To estimate initial microtubule length or intensity as well as rate of microtubule length and fluorescence change separately for

individual microtubule growth or shrinkage phases and strains, we used ordinary linear regression on the respective partial trajectories. For joint estimation (over length or intensity data

for all strains during growth or shrinkage; Fig. 5f,g), we used linear mixed effects models51 where the interactions between intercept and slope with strain were the fixed effects, and

intercept and slope could vary by partial trajectories. Model parameters were estimated by maximum likelihood estimation and significance of fixed-effects coefficients was determined by

two-sided _t_-tests. Automatic classification and regression were implemented in MATLAB R2019b. For stoichiometry analysis, the _z_-stacks were maximum projected and Kar9 and Dam1

intensities (raw integrated density) were measured after subtracting the cell background. For estimating the brilliance of one Dam1-mNeonGreen molecule, we divided the median value of

metaphase punctum intensity (912) by 272 (16 kinetochores × 17 molecules per kinetochore). We assumed that the brilliance of one Dam1-mNeonGreen of 3.35 a.u. is similar to that of one

molecule of Kar9-mNeonGreen. Thus, to calculate the amount of Kar9 molecules at the microtubule tip during metaphase we divided the mean value of the Kar9 punctum intensity during metaphase

(244 a.u.) by the calculated brilliance of one mNeonGreen molecule (3.35 a.u.), resulting in 72.9 Kar9 molecules at the tip of one astral microtubule. For calculating the levels of

overexpressed Kar9, we multiplied the measured intensity of the punctum by the factor (2.5) between the exposure times of overexpressed (100 ms) and endogenous Kar9 or two copies of _KAR9_

(250 ms). For significance analysis, we used two-tailed Welch’s _t_-test for continuous data and two-tailed two-proportion _z_-test for nominal data. The used test is indicated in the figure

legend for each panel. DISORDER PREDICTION For prediction of disordered protein regions, flDPnn52 was used. STATISTICS AND REPRODUCIBILITY No statistical method was used to pre-determine

sample size. No data were excluded from the analyses. The experiments were not randomized. The investigators were not blinded for data analysis. Owing to high protein consumption, phase

separation and other in vitro experiments (Figs. 1d,e, 2b,d,e, 3a and 7c and Extended Data Figs. 1 and 2d,e) were performed only once. For live cell experiments, the number of biological

replicates (genetically identical clones) are indicated in the figures or figure legends. Notably, tip tracking experiments (Figs. 5e,f,g and 7b and Extended Data Fig. 8), stoichiometry

analysis (Fig. 6) and hexanediol experiments (Fig. 7d,e and Extended Data Fig. 9) were performed only once. For a summary of materials and software used in this manuscript, see Supplementary

Table 1. REPORTING SUMMARY Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article. DATA AVAILABILITY All data and any

additional information required to re-analyse the data reported in this paper are available from the lead contact upon request. Further information and requests for resources and reagents

should be directed to and will be fulfilled by the lead contact, Y.B. ([email protected]). The previously published and re-analysed structure of _Naumovozyma castellii_ Kar9

N-terminal domain is available from PDB under accession code 7AG9. Source data are provided with this paper. CODE AVAILABILITY Code used for data analysis is available from the lead contact

upon request. REFERENCES * Prosser, S. L. & Pelletier, L. Mitotic spindle assembly in animal cells: a fine balancing act. _Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol._ 18, 187–201 (2017). Article CAS

Google Scholar * Akhmanova, A. & Steinmetz, M. O. Tracking the ends: a dynamic protein network controls the fate of microtubule tips. _Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol._ 9, 309–322 (2008).

Article CAS Google Scholar * Akhmanova, A. & Steinmetz, M. O. Control of microtubule organization and dynamics: two ends in the limelight. _Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol._ 16, 711–726

(2015). Article CAS Google Scholar * Kumar, A. et al. Structure and regulation of the microtubule plus-end tracking protein Kar9. _Structure_ 29, 1266–1278 (2021). Article CAS Google

Scholar * Sonnenberg, A. & Liem, R. K. Plakins in development and disease. _Exp. Cell Res._ 313, 2189–2203 (2007). Article CAS Google Scholar * van der Vaart, B. et al. Microtubule

plus-end tracking proteins SLAIN1/2 and ch-TOG promote axonal development. _J. Neurosci._ 32, 14722–14728 (2012). Article Google Scholar * Nelson, S. & Näthke, I. S. Interactions and

functions of the adenomatous polyposis coli (APC) protein at a glance. _J. Cell Sci._ 126, 873–877 (2013). Article CAS Google Scholar * Manatschal, C. et al. Molecular basis of Kar9–Bim1

complex function during mating and spindle positioning. _Mol. Biol. Cell_ 27, 3729–3745 (2016). Article CAS Google Scholar * Lengefeld, J. & Barral, Y. Asymmetric segregation of aged

spindle pole bodies during cell division: mechanisms and relevance beyond budding yeast? _Bioessays_ 40, e1800038 (2018). Article Google Scholar * Gupta, M. L. Jr. et al. β-Tubulin C354

mutations that severely decrease microtubule dynamics do not prevent nuclear migration in yeast. _Mol. Biol. Cell_ 13, 2919–2932 (2002). Article CAS Google Scholar * Saunders, W.,

Hornack, D., Lengyel, V. & Deng, C. The _Saccharomyces cerevisiae_ kinesin-related motor Kar3p acts at preanaphase spindle poles to limit the number and length of cytoplasmic

microtubules. _J. Cell Biol._ 137, 417–431 (1997). Article CAS Google Scholar * Chen, X. et al. Remote control of microtubule plus-end dynamics and function from the minus-end. _eLife_ 8,

e48627 (2019). Article CAS Google Scholar * Lengefeld, J. et al. Spatial cues and not spindle pole maturation drive the asymmetry of astral microtubules between new and preexisting

spindle poles. _Mol. Biol. Cell_ 29, 10–28 (2018). Article CAS Google Scholar * Segal, M. & Bloom, K. Control of spindle polarity and orientation in _Saccharomyces cerevisiae_.

_Trends Cell Biol._ 11, 160–166 (2001). Article CAS Google Scholar * Shaw, S. L., Yeh, E., Maddox, P., Salmon, E. D. & Bloom, K. Astral microtubule dynamics in yeast: a

microtubule-based searching mechanism for spindle orientation and nuclear migration into the bud. _J. Cell Biol._ 139, 985–994 (1997). Article CAS Google Scholar * Hotz, M. et al. Spindle

pole bodies exploit the mitotic exit network in metaphase to drive their age-dependent segregation. _Cell_ 148, 958–972 (2012). Article CAS Google Scholar * Pereira, G., Tanaka, T. U.,

Nasmyth, K. & Schiebel, E. Modes of spindle pole body inheritance and segregation of the Bfa1p–Bub2p checkpoint protein complex. _EMBO J._ 20, 6359–6370 (2001). Article CAS Google

Scholar * Kusch, J., Liakopoulos, D. & Barral, Y. Spindle asymmetry: a compass for the cell. _Trends Cell Biol._ 13, 562–569 (2003). Article CAS Google Scholar * Kusch, J., Meyer,

A., Snyder, M. P. & Barral, Y. Microtubule capture by the cleavage apparatus is required for proper spindle positioning in yeast. _Genes Dev._ 16, 1627–1639 (2002). Article CAS Google

Scholar * Liakopoulos, D., Kusch, J., Grava, S., Vogel, J. & Barral, Y. Asymmetric loading of Kar9 onto spindle poles and microtubules ensures proper spindle alignment. _Cell_ 112,

561–574 (2003). Article CAS Google Scholar * Korinek, W. S., Copeland, M. J., Chaudhuri, A. & Chant, J. Molecular linkage underlying microtubule orientation toward cortical sites in

yeast. _Science_ 287, 2257–2259 (2000). Article CAS Google Scholar * Miller, R. K., Cheng, S. C. & Rose, M. D. Bim1p/Yeb1p mediates the Kar9p-dependent cortical attachment of

cytoplasmic microtubules. _Mol. Biol. Cell_ 11, 2949–2959 (2000). Article CAS Google Scholar * Moore, J. K., D’Silva, S. & Miller, R. K. The CLIP-170 homologue Bik1p promotes the

phosphorylation and asymmetric localization of Kar9p. _Mol. Biol. Cell_ 17, 178–191 (2006). Article CAS Google Scholar * Beach, D. L., Thibodeaux, J., Maddox, P., Yeh, E. & Bloom, K.

The role of the proteins Kar9 and Myo2 in orienting the mitotic spindle of budding yeast. _Curr. Biol._ 10, 1497–1506 (2000). Article CAS Google Scholar * Yin, H., Pruyne, D., Huffaker,

T. C. & Bretscher, A. Myosin V orientates the mitotic spindle in yeast. _Nature_ 406, 1013–1015 (2000). Article CAS Google Scholar * Zimniak, T., Stengl, K., Mechtler, K. &

Westermann, S. Phosphoregulation of the budding yeast EB1 homologue Bim1p by Aurora/Ipl1p. _J. Cell Biol._ 186, 379–391 (2009). Article CAS Google Scholar * Honnappa, S. et al. An

EB1-binding motif acts as a microtubule tip localization signal. _Cell_ 138, 366–376 (2009). Article CAS Google Scholar * Honnappa, S., John, C. M., Kostrewa, D., Winkler, F. K. &

Steinmetz, M. O. Structural insights into the EB1–APC interaction. _EMBO J._ 24, 261–269 (2005). Article CAS Google Scholar * Stangier, M. M. et al. Structure–function relationship of the

Bik1–Bim1 complex. _Structure_ 26, 607–618 (2018). Article CAS Google Scholar * Weisbrich, A. et al. Structure–function relationship of CAP-Gly domains. _Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol._ 14,

959–967 (2007). Article CAS Google Scholar * Miller, R. K., D’Silva, S., Moore, J. K. & Goodson, H. V. The CLIP-170 orthologue Bik1p and positioning the mitotic spindle in yeast.

_Curr. Top. Dev. Biol._ 76, 49–87 (2006). Article CAS Google Scholar * Miesch, J., Wimbish, R.T., Velluz, M.-C. & Aumeier, C. Phase separation of +TIP-networks regulates microtubule

dynamics. Preprint at https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.09.13.459419v4 (2022). * Maan, R. et al. Multivalent interactions facilitate motor-dependent protein accumulation at growing microtubule

plus-ends. _Nat. Cell Biol._ https://doi.org/10.1038/s41556-022-01037-0 (2022). * Song, X. et al. Phase separation of EB1 guides microtubule plus-end dynamics. _Nat. Cell Biol._

https://doi.org/10.1038/s41556-022-01033-4 (2022). * Ijavi, M. et al. Surface tensiometry of phase separated protein and polymer droplets by the sessile drop method. _Soft Matter_ 17,

1655–1662 (2021). Article CAS Google Scholar * Kumar, A. et al. Short linear sequence motif LxxPTPh targets diverse proteins to growing microtubule ends. _Structure_ 25, 924–932 (2017).

Article CAS Google Scholar * Miller, R. K. & Rose, M. D. Kar9p is a novel cortical protein required for cytoplasmic microtubule orientation in yeast. _J. Cell Biol._ 140, 377–390

(1998). Article CAS Google Scholar * Sheeman, B. et al. Determinants of _S. cerevisiae_ dynein localization and activation: implications for the mechanism of spindle positioning. _Curr.

Biol._ 13, 364–372 (2003). Article CAS Google Scholar * Banani, S. F., Lee, H. O., Hyman, A. A. & Rosen, M. K. Biomolecular condensates: organizers of cellular biochemistry. _Nat.

Rev. Mol. Cell Biol._ 18, 285–298 (2017). Article CAS Google Scholar * Jenni, S. & Harrison, S. C. Structure of the DASH/Dam1 complex shows its role at the yeast

kinetochore-microtubule interface. _Science_ 360, 552–558 (2018). Article CAS Google Scholar * Joglekar, A. P., Bouck, D. C., Molk, J. N., Bloom, K. S. & Salmon, E. D. Molecular

architecture of a kinetochore–microtubule attachment site. _Nat. Cell Biol._ 8, 581–585 (2006). Article CAS Google Scholar * Kroschwald, S. & Alberti, S. Gel or die: phase separation

as a survival strategy. _Cell_ 168, 947–948 (2017). Article CAS Google Scholar * Wheeler, R. J. & Hyman, A. A. Controlling compartmentalization by non-membrane-bound organelles.

_Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B_ 373, 20170193 (2018). Article Google Scholar * Geyer, E. A. et al. A mutation uncouples the tubulin conformational and GTPase cycles, revealing allosteric

control of microtubule dynamics. _eLife_ 4, e10113 (2015). Article Google Scholar * Olieric, N. et al. Automated seamless DNA co-transformation cloning with direct expression vectors

applying positive or negative insert selection. _BMC Biotechnology_ 10, 56 (2010). Article Google Scholar * Bieniossek, C. et al. Automated unrestricted multigene recombineering for

multiprotein complex production. _Nature Methods_ 6, 447–450 (2009). Article CAS Google Scholar * Jeon, B. J. et al. Salt-dependent properties of a coacervate-like, self-assembled DNA

liquid. _Soft Matter_ 14, 7009–7015 (2018). Article CAS Google Scholar * Leal, L. _Advanced Transport Phenomena: Fluid Mechanics and Convective Transport Processes_ (Cambridge Univ.

Press, 2007). * Krissinel, E. & Henrick, K. Inference of macromolecular assemblies from crystalline state. _J. Mol. Biol._ 372, 774–797 (2007). Article CAS Google Scholar *

Schindelin, J. et al. Fiji: an open-source platform for biological-image analysis. _Nat. Methods_ 9, 676–682 (2012). Article CAS Google Scholar * Gelman, A. & Hill, J. _Data Analysis

Using Regression and Multilevel/Hierarchical Models (Analytical Methods for Social Research)_ Ch. 12–13 (Cambridge University Press, 2006). * Hu, G. et al. flDPnn: accurate intrinsic

disorder prediction with putative propensities of disorder functions. _Nat. Commun._ 12, 4438 (2021). Article CAS Google Scholar Download references ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS We thank M.

Choudhury, M. Bayer and T. Vukovic for their help with the experiments, M. Stangier for helping with protein production and ScopeM for their support and assistance with microscopy. We thank

previous and current members of the Steinmetz, Dufresne and Barral laboratories for extensive and critical discussions throughout the project. This work was supported by a Marie Curie COFUND

fellowship (to A.K.) and by grants from the Swiss National Science Foundation (31003A-105904 to Y.B. and 31003A_166608 and 310030_192566 to M.O.S.; Sinergia CRSII5_189940 to Y.B., M.O.S.

and E.R.D.) and from SystemsX.ch (RTD grant #2012/192 TubeX, to M.O.S., J.S. and Y.B.). AUTHOR INFORMATION Author notes * Anil Kumar Present address: ImmunOs Therapeutics AG, Schlieren,

Switzerland * Robert T. Bill Present address: Department of Molecular Life Sciences, University of Zürich, Zürich, Switzerland * These authors contributed equally: Sandro M. Meier, Ana-Maria

Farcas, Anil Kumar. AUTHORS AND AFFILIATIONS * Laboratory of Biomolecular Research, Division of Biology and Chemistry, Paul Scherrer Institut, Villigen, Switzerland Sandro M. Meier, Anil

Kumar & Michel O. Steinmetz * Department of Biology, Institute of Biochemistry, ETH Zürich, Zürich, Switzerland Sandro M. Meier, Ana-Maria Farcas, Robert T. Bill & Yves Barral *

Bringing Materials to Life Initiative, ETH Zürich, Zürich, Switzerland Sandro M. Meier, Ana-Maria Farcas, Mahdiye Ijavi, Eric R. Dufresne & Yves Barral * Department of Materials, ETH

Zürich, Zürich, Switzerland Mahdiye Ijavi & Eric R. Dufresne * Department of Biosystems Science and Engineering and SIB Swiss Institute of Bioinformatics, ETH Zürich, Basel, Switzerland

Jörg Stelling * University of Basel, Biozentrum, Basel, Switzerland Michel O. Steinmetz Authors * Sandro M. Meier View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google

Scholar * Ana-Maria Farcas View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Anil Kumar View author publications You can also search for this author

inPubMed Google Scholar * Mahdiye Ijavi View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Robert T. Bill View author publications You can also search for

this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Jörg Stelling View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Eric R. Dufresne View author publications You can

also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Michel O. Steinmetz View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Yves Barral View author

publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar CONTRIBUTIONS The authors S.M.M., A.-M.F. and A.K. contributed equally. S.M.M., A.-M.F. and A.K. designed and

performed the research, and analysed the data. M.I. characterized the material properties of the different droplets in vitro. J.S. designed and executed the quantitative analysis of Kar9

levels on shrinking microtubules. R.T.B. designed and performed the analysis of Kar9 overexpression with A.-M.F. E.R.D. contributed to designing the research and supervised the work of M.I.

Y.B. and M.O.S. designed and supervised the research, analysed the data and wrote the manuscript with input from all authors. CORRESPONDING AUTHORS Correspondence to Michel O. Steinmetz or

Yves Barral. ETHICS DECLARATIONS COMPETING INTERESTS The authors declare no competing interests. PEER REVIEW PEER REVIEW INFORMATION _Nature Cell Biology_ thanks Carsten Janke and the other,

anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Peer reviewer reports are available. ADDITIONAL INFORMATION PUBLISHER’S NOTE Springer Nature remains neutral

with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. EXTENDED DATA EXTENDED DATA FIG. 1 FLUORESCENCE RECOVERY AFTER PHOTOBLEACHING (FRAP) OF IN VITRO

PROTEIN DROPLETS. Time series (left) displaying fluorescence recovery in the indicated protein droplets after a bleaching laser pulse and quantification (right). Tenfold less concentrated

labeled protein (mNeonGreen-Bik1, Bim1-GFP, or Kar9-GFP, indicated with green letter fonts) was added to mixtures of unlabeled protein (5 μM each). Blue line displays fluorescence intensity

over time of a single experiment normalized to prebleached droplet intensity, grey dotted line is a single exponential decay fitted to the recovery period. Half-lives (t1/2) of the fitted

decay are given with 95% confidence intervals of the fit. For Bik1 droplets, the quantified intensity was corrected for the effect of defocusing according to unbleached reference droplets.

Scale bar 3 μm. Single experiment. Related to Fig. 1. Source numerical data available in source data. Source data EXTENDED DATA FIG. 2 PARTITION COEFFICIENTS AND PHASE DIAGRAM WITH VARIABLE

KAR9 IN CONSTANT BIM1 AND BIK1. A, Partition coefficients (ratio between fluorescence intensity inside and outside of droplets) for mNeonGreen-Bik1, Bim1-GFP, Kar9-GFP, and mNeonGreen into

non-fluorescent, equimolar mixtures of Kar9 + Bim1 + Bik1, Kar9 + Bim1, and Bik1 droplets (10 μM each; median with 95% confidence interval). Blue values indicate _n_ analyzed droplets,

single experiment. B, Phase diagram of Kar9 that was titrated into an equimolar mixture of Bim1 + Bik1 (10 μM each). Single experiment. Related to Fig. 1. Source numerical data available in

source data. Source data EXTENDED DATA FIG. 3 DISORDER PREDICTION FOR KAR9, BIM1, AND BIK1. Disorder propensity calculated by flDPnn52 visualizing the disordered regions of Kar9, Bim1, and

Bik1 with annotations for known folded domains and amino acid compositional biases. The 0.3 threshold level for disorder is indicated by dotted lines. Related to Fig. 2. Source numerical

data available in source data. Source data EXTENDED DATA FIG. 4 PROTOMER CONTACTS FORMING THE NCKAR9N CRYSTAL AND NCKAR9 DIMER INTERFACE MUTAGENESIS. A-C, Close-up views of the α (A), β (B),

and γ (C) interfaces seen between protomers in the NcKar9N crystal (PDB ID 7AG9). Interacting residue side chains are shown in stick representation. Oxygen and nitrogen atoms are colored in

red and blue, respectively; carbon atoms are in dark green for chain A and in light green for chains B, C, and D. Interface residues that were mutated in the three crystallographic dimers

are labeled in bold and blue lettering. D and E, Far-ultraviolet CD spectra (D) and thermal denaturation profiles (E) of His-NcKar9N (red), His-NcKar9N-α− (blue), His-NcKar9N-β− (yellow),

and His-NcKar9N-γ− (magenta). Inset in (E), SDS-PAGE analysis of the His-NcKar9N variants. Spectra are averages of 3 measurements of the same sample, denaturation profiles are single

experiments. Related to Fig. 2. EXTENDED DATA FIG. 5 MULTIPLE SEQUENCE ALIGNMENT OF KAR9 HOMOLOGUES. Multiple sequence alignment of Kar9 homologues of closely and distantly related yeast

species. Conserved amino acid residues are indicated by the background color from strong (red) to no (blue) conservation, as well as by grey bars below the alignment. Consensus amino acids

are indicated by the size of the letters below the alignment. Kar9 self-oligomerization interfaces are denoted by magenta (α), blue (β) and green (γ) arrowheads. Interface residues that were

mutated in this study are indicated by asterisk in identical color. Related to Fig. 2. EXTENDED DATA FIG. 6 BUDDING YEAST GROWTH SPOT ASSAY. Spot assays with serial 10X dilutions starting

at OD600 = 0,05 performed at 25, 33, and 35 °C. Single experiment. Related to Fig. 4a. EXTENDED DATA FIG. 7 KAR9 QUANTIFICATION ON ASTRAL MICROTUBULES. Quantification of cumulative Kar9

fluorescence intensity on astral microtubules emanating from both spindle poles (normalized median with 95% confidence interval). Unless specified in the legend. Blue values indicate _n_ =

cells analyzed / number of biological replicates. Related to Fig. 5a,b. Source numerical data available in source data. Source data EXTENDED DATA FIG. 8 ANALYSIS OF MICROTUBULE AND KAR9

PUNCTA DYNAMICS. A, Trajectories of microtubule (MT) length (top) and Kar9-mNeonGreen fluorescence intensity (bottom) extracted during individual microtubule growth (left) and shrinkage

(right) phases in wild-type cells. B, Estimates of initial microtubule length (top; defined as the length at the start of a growth or shrinkage phase) and growth/shrinkage rate (bottom)

during microtubule growth (left) and shrinkage (right) phases using linear regression for individual trajectories in the indicated strains. Dots, estimates for individual trajectories; long

lines, medians; short lines, 50% quantiles. C, As panel B but for fluorescence intensity of Kar9 puncta. D, Durations of microtubule growth and shrinkage phases. _P_ values were determined

by Wilcoxon rank sum test. For panels B-D, blue values indicate _n_ = number of microtubule growth/shrinkage events analyzed, single experiment. E, As Fig. 5f,g, but showing the linear

mixed-effects (LME) model estimates of initial microtubule lengths and Kar9-mNeonGreen fluorescence intensity levels at the start of microtubule growth and shrinkage phases. Color of _P_

values (two-sided _t_-test) and _n_ (number of timeframes considered for the model, single experiment) matches the growth/shrinkage category they refer to. Related to Fig. 5. Source

numerical data available in source data. Source data EXTENDED DATA FIG. 9 HEXANEDIOL AND NOCODAZOLE TREATMENT. A, Micrographs of mNeonGreen-Bim1 and mNeonGreen-Bik1 expressing control and 5%

hexanediol treated cells as quantified in Fig. 7e. Since these cells did not express CFP-Tub1, the transmission channel is used as a reference in magenta. Scale bar, 3 μm. B, Micrographs of

GFP-Tub1 expressing control, 5% hexanediol, and 30 μg/mL nocodazole treated cells. C, Frequency of cells with visible astral microtubules labeled with GFP-Tub1 in control, 5% hexanediol,

and 30 μg/mL nocodazole treatment (error bars are Wilson/Brown 95% confidence intervals determined from binomial distribution). _P_ values above bars are determined by two-proportion z test.

D, Micrographs of cells expressing Kar9-mNeonGreen treated with 30 μg/mL nocodazole versus control. E, Kar9-mNeonGreen fluorescence intensity levels in wild-type cells treated with 5%

hexanediol or 30 μg/mL nocodazole versus untreated control (normalized median with 95% confidence intervals, the control and 5% hexanediol data are the same as shown in Fig. 7e). _P_ values

were determined by Welch’s _t_-test. Blue values in panels C,E indicate _n_ = number of cells analyzed, single experiment. Related to Fig. 7d,e. Source numerical data available in source

data. Source data EXTENDED DATA FIG. 10 DROPLET FUSION TIME QUANTIFICATION EXAMPLE. Fusion of two Bik1 droplets at a later stage can be considered as a uni-axially deformed droplet reaching

its final spherical state, driven by surface tension. Parameter A relates the major and minor axis of the droplet (L and W, respectively) and is plotted versus time, where an exponential fit

allows to calculate the fusion time τ. Example of the analysis of a single fusion event. Scale bar in the inlet, 5 μm. Related to Fig. 1e. SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION REPORTING SUMMARY PEER

REVIEW FILE SUPPLEMENTARY TABLE 1 Table summarizing materials used and created in this study as well as software packages used. SUPPLEMENTARY MOVIE 1 In vitro condensate behaviour. Movie

showing behaviour of Kar9 + Bim1 + Bik1 in vitro protein condensate as presented in Fig. 1b. SUPPLEMENTARY MOVIE 2 In vitro condensate behaviour. Movie showing behaviour of Kar9 + Bim1 in

vitro protein condensate as presented in Fig. 1b. SUPPLEMENTARY MOVIE 3 In vitro condensate behaviour. Movie showing behaviour of Kar9 + Bik1 in vitro protein condensate as presented in Fig.

1b. SUPPLEMENTARY MOVIE 4 In vitro condensate behaviour. Movie showing behaviour of Bik1 in vitro protein condensate as presented in Fig. 1b. SUPPLEMENTARY MOVIE 5 In vitro condensate

behaviour. Movie showing dissolution of Bik1 in vitro condensate by addition of Bim1 as presented in Fig. 1b. SUPPLEMENTARY MOVIE 6 In vitro condensate behaviour. Movie showing behaviour of

Kar9 in vitro protein precipitate as presented in Fig. 1b. SUPPLEMENTARY MOVIE 7 Microtubule plus-end tracking of wild-type +TIP body. Movie showing microtubule plus-end tracking behaviour

of +TIP body in wild-type cell as presented in Fig. 5c. Kar9-mNeonGreen (green) and Spc42-mCherry (magenta). SUPPLEMENTARY MOVIE 8 Microtubule plus-end tracking of mutant +TIP body. Movie

showing microtubule plus-end tracking behaviour of +TIP body in _kar9-αβγ__−_ _bik1Δ_ cell as presented in Fig. 5c. Kar9-mNeonGreen (green) and Spc42-mCherry (magenta). SUPPLEMENTARY MOVIE 9

Multiple +TIP bodies fusing into one. Movie displaying fusion of +TIP bodies as shown in Fig. 7a (top example). Kar9-mNeonGreen (green) and Spc42-mCherry (magenta). SOURCE DATA SOURCE DATA

FIG. 1 Numerical source data Fig. 1. SOURCE DATA FIG. 1 Unprocessed gels Fig. 1. SOURCE DATA FIG. 2 Numerical source data Fig. 2. SOURCE DATA FIG. 3 Numerical source data Fig. 3. SOURCE DATA

FIG. 4 Numerical source data Fig. 4. SOURCE DATA FIG. 5 Numerical source data Fig. 5. SOURCE DATA FIG. 6 Numerical source data Fig. 6. SOURCE DATA FIG. 7 Numerical source data Fig. 7.

SOURCE DATA EXTENDED DATA FIG. 1 Numerical source data extended data for Fig. 1. SOURCE DATA EXTENDED DATA FIG. 2 Numerical source data extended data for Fig. 2. SOURCE DATA EXTENDED DATA

FIG. 3 Numerical source data extended data for Fig. 3. SOURCE DATA EXTENDED DATA FIG. 7 Numerical source data extended data for Fig. 7. SOURCE DATA EXTENDED DATA FIG. 8 Numerical source data

extended data for Fig. 8. SOURCE DATA EXTENDED DATA FIG. 9 Numerical source data extended data for Fig. 9. RIGHTS AND PERMISSIONS OPEN ACCESS This article is licensed under a Creative

Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the

original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in