Cathepsin g degrades both glycosylated and unglycosylated regions of lubricin, a synovial mucin

- Select a language for the TTS:

- UK English Female

- UK English Male

- US English Female

- US English Male

- Australian Female

- Australian Male

- Language selected: (auto detect) - EN

Play all audios:

ABSTRACT Lubricin (PRG4) is a mucin type protein that plays an important role in maintaining normal joint function by providing lubrication and chondroprotection. Improper lubricin

modification and degradation has been observed in idiopathic osteoarthritis (OA), while the detailed mechanism still remains unknown. We hypothesized that the protease cathepsin G (CG) may

participate in degrading lubricin in synovial fluid (SF). The presence of endogenous CG in SF was confirmed in 16 patients with knee OA. Recombinant human lubricin (rhPRG4) and native

lubricin purified from the SF of patients were incubated with exogenous CG and lubricin degradation was monitored using western blot, staining by Coomassie or Periodic Acid-Schiff base in

gels, and with proteomics. Full length lubricin (∼300 kDa), was efficiently digested with CG generating a 25-kDa protein fragment, originating from the densely glycosylated mucin domain

(∼250 kDa). The 25-kDa fragment was present in the SF from OA patients, and the amount was increased after incubation with CG. A CG digest of rhPRG4 revealed 135 peptides and 72

glycopeptides, and confirmed that the protease could cleave in all domains of lubricin, including the mucin domain. Our results suggest that synovial CG may take part in the degradation of

lubricin, which could affect the pathological decrease of the lubrication in degenerative joint disease. SIMILAR CONTENT BEING VIEWED BY OTHERS TRYPTASE Β REGULATION OF JOINT LUBRICATION AND

INFLAMMATION VIA PROTEOGLYCAN-4 IN OSTEOARTHRITIS Article Open access 06 April 2023 ANALYSIS OF PROTEINS RELEASED FROM OSTEOARTHRITIC CARTILAGE BY COMPRESSIVE LOADING Article Open access 25

October 2023 PROTEINS INVOLVED IN THE ENDOPLASMIC RETICULUM STRESS ARE MODULATED IN SYNOVITIS OF OSTEOARTHRITIS, CHRONIC PYROPHOSPHATE ARTHROPATHY AND RHEUMATOID ARTHRITIS, AND CORRELATE

WITH THE HISTOLOGICAL INFLAMMATORY SCORE Article Open access 04 September 2020 INTRODUCTION Lubricin, also known as Proteoglycan 4 (PRG4) is a large (∼300 kDa) extensively _O_-linked

glycosylated mucinous protein in SF that plays a critical role in maintaining cartilage integrity by providing boundary lubrication and reducing friction at the cartilage surface1. Besides

the principle function of lubrication, lubricin also has growth-regulating properties2, prevents cell adhesion, provides chondroprotection3,4,5, and plays a role in the maturation of the

subchondral bone6. Lubricin is predominantly synthesized and expressed by superficial zone chondrocytes at the cartilage surface layer7, but can also be secreted into the SF by synovial

fibroblasts8 and stromal cells from peri-articular adipose tissues9. More recently it was reported that other sites and tissues, such as tendons, liver, kidney, skeletal muscles, and the

ocular surface, also express lubricin10,11,12. In the joint, lubricin is an extended molecule existing both as monomers and as higher molecular mass complexes11. Lubricin has an

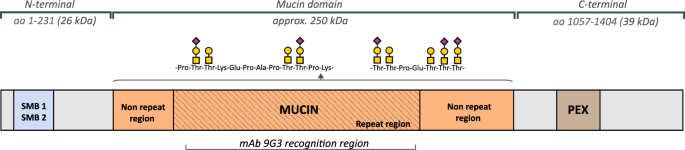

approximately equal mass proportion of protein and oligosaccharides, and contains one central mucin-like region, two somatomedin B homology domains (SMB) in the _N_-terminal, one heparin or

chondroitin sulfate binding domain, and one hemopexin-like domain (PEX)10,13 in the _C_-terminal (Fig. 1). The multiple domain structure contributes to diverse biological roles of lubricin.

The _O_-linked oligosaccharides in the mucin domain render lubricin a low friction brush-like construct with repulsive hydration forces, provide lubrication during boundary movement, and

makes lubricin water-soluble in SF14. The oligosaccharides are mostly linked to abundant Thr residues, which are found in the repeat region, consisting of repeats with minor variations of

the amino acid sequence ‘EPAPTTPK’, as well as its flanking, non-repeating Thr/Ser rich regions. The sparingly glycosylated terminal regions SMB and PEX domains have in other proteins been

demonstrated to regulate innate immune processes by interacting with both complement and coagulation factors15 and assisting matrix protein binding16. For over a decade, researchers have

demonstrated that lubricin plays a vital role in inflammatory joint disease. Prevention of lubricin degradation may serve as a therapy in an early stage inflammatory arthritis17,18,19,20,21.

Altered lubricin structure and change of lubricin concentrations, which disrupts cartilage boundary lubrication, is found in SF of Osteoarthritis (OA) patients22. As such, lubricin

degradation may play a role in OA associated inflammation. OA is the most common degenerative joint disease, which affects people worldwide23. The disease involves a progressive destruction

of cartilage, bone and ligaments, sometimes causing extensive pain, reduced joint flexibility and may lead to severely impaired quality of life and rising health care costs. Recent research

emphasizes idiopathic OA as a multifactorial joint disease24 with an increasing number of studies demonstrating a low-grade inflammation and an accumulation of pro-inflammatory cytokines in

synovial fluid (SF), which is associated with the pathological process of OA25. Cytokine triggered enzymatic degradation of matrix proteins is believed to contribute to the cartilage erosion

found in OA26,27,28,29. A limited number of proteases have been identified to degrade lubricin, among the more studied are lysosomal cysteine proteases cathepsin B, S, L and neutrophil

elastase19,21,30. Cathepsin G (CG) is one of the major neutrophil serine proteases that is synthesized in bone marrow and subsequently stored in the azurophil granules of polymorphonuclear

neutrophils31,32. CG exhibit optimal activity in a broad pH range (pH 7–8)33, operational in the pH level reported for SF is (pH 7.5–7.78)34. Upon activation of the granulocytes, CG is

released at sites of inflammation and plays a crucial part in degrading chemokines and extracellular matrix (ECM) proteins, as well as regulating and activating pro-inflammatory cytokines35.

Therefore, CG is reported to be active in various chronic inflammatory diseases36 and has for instance been shown to be highly active in the SF of rheumatoid arthritis patients. CG has also

been reported to be present in OA synovial fluid37 and synovial lining38. Despite evidence indicating that lubricin modification contributes to some to OA initiation and pathological

development, research and understanding of enzymatic degradation of lubricin in OA is still limited. Our data confirmed previous reports of endogenous CG in OA, by detection of the 29 kDa

protease in a panel of SF samples from 16 patients with idiopathic knee OA. This initiated the investigation of the ability of CG to degrade lubricin. A 25 kDa lubricin fragment constituting

part of its mucin domain was identified in these patients. The relative abundance of this fragment was increased after incubation of exogenous CG added to OA SF. In addition, CG generated

fragments of recombinant lubricin were identified using proteomics. RESULTS DETECTION OF A SYNOVIAL CG: WESTERN BLOT CONFIRMATION OF CG IN SYNOVIAL FLUIDS OF OA SUBJECTS CG has previously

been shown to be present in OA SF, however in a low abundance compared to SF from rheumatoid arthritis patients37. We verified in our SF sample collection that CG was present in OA. SF

samples were collected from 16 late-stage OA patients and analyzed for the presence of CG using SDS-PAGE and western blot with a polyclonal anti-CG antibody. We could detect CG in all the SF

samples (Fig. 2). By including 22 ng/μL CG in a separate lane as a positive control, it was obvious that the amount of CG in the SF samples was in line with a previous study where a

concentration of 1–5 ng/μL CG in OA SF was reported37. This data inspired us to further investigate the connection between lubricin and CG degradation. CG DEGRADES RECOMBINANT AND NATIVE

LUBRICIN In order to investigate if CG was able to digest lubricin, we performed incubations using recombinant lubricin (rhPRG4). The full length glycosylated protein and its degradation

products were separated with SDS-PAGE and detected with lubricin mAb 9G3. This antibody targets part of the glycosylated mucin domain12 (Fig. 1). The results indicated that rhPRG4 was indeed

degraded after extended incubation, by observing the decreased antibody staining intensity of the full length protein in conjunction with a major degradation product detected at

approximately 25 kDa (Fig. 3a). To compare differences in the ability of CG to digest different forms of lubricin, we monitored the degradation using rhPRG4 and native lubricin purified from

patients using a Coomassie protein staining. Coomassie was chosen rather than mAb 9G3 western blot, since we initially wanted to monitor CG degradation of the unglycosylated _N-_ and

_C_-terminal regions, hypothesizing that they were its primary targets. Both rhPRG4 and native lubricin purified from SF were found to be degraded in a dose-dependent manner. The degradation

of rhPRG4 and native lubricin was found to increase with prolonged incubation time (Fig. 3b,c and Supplementary Figs. S2 and S3). No major bands of lower molecular mass peptide products

were detected in the Coomassie stained SDS-PAGE gels in neither of the lubricin forms. This indicated that most generated non-glycosylated peptides were of low molecular mass (<10 KDa)

below the SDS-PAGE range. However, the two lubricin forms were found to be degraded at different rates. rhPRG4 was found to be efficiently degraded by CG already after 30 minutes of

incubation. This was illustrated by a semiquantitative measurement using the Coomassie stain, showing in one of the experiment that 32%, 54% and 84% of the full length protein had been

degraded with increasing CG-to-protein ratio, respectively. In this experiment, rhPRG4 was completely degraded after 16 hours (0.1% left) (Fig. 3b) using the highest concentration of CG (2.5

w/w %CG). Native lubricin was found to be more resilient to CG digestion. After 16 hours of incubation with the higher CG concentrations (0.5 and 2.5 w/w % CG), 30 and 21% of the full

length lubricin remained undigested, respectively. (Fig. 3c). Similar difference between the susceptibility of rhPRG4 and native lubricin to CG degradation was found in repeat experiments

(Supplementary Figs. S2 and S3). These results suggested that the protein core of native lubricin was less accessible for CG digestion. However, while the bulk of natural SF protease

inhibitors are removed using ion exchange chromatography in the purification of native lubricin, proteomic analysis indicated that low level still remained39. In order to monitor the effect

of endogenous CF proteases, we measured the difference between native lubricin degradation by supplementing SF (high level of proteases inhibitor) with exogenous CG and compared to when CG

was added to purified native lubricin (protease inhibitor depleted) in PBS. For this we adopted a sandwich ELISA (Materials and Methods) to be able to monitor lubricin in presence of other

proteins. With this ELISA we could show that the high level of protease inhibitors present in SF significantly influenced the degradation of lubricin (Fig. 3d). Finally, to confirm that

lubricin degradation was due to CG, the degradation of purified SF lubricin was shown to be totally abolished using CG inhibitors (Supplementary Fig. S4). In all, we concluded that CG was

capable of degrading lubricin both in its recombinant and native form and that natural SF proteases inhibitor inhibited the CG activity. CG DEGRADES THE LUBRICIN MUCIN DOMAIN The decrease in

Coomassie stain of lubricin after incubation with CG (Fig. 3b,c and Supplementary Figs. S2 and S3) indicated that the unglycosylated protein parts was substantially effected. In addition,

using mAb 9G3 based detection in western blot (Fig. 3a) and ELISA (Fig. 3d), indicated that CG was a potent protease also capable of attacking the lubricin glycosylated mucin domain. Mucin

domains are renowned for being hard to digest with proteolytic enzymes. In order to monitor how the whole mucin domain was affected by CG degradation and not only the region recognized by

mAb 9G3, we adopted the carbohydrate sensitive Periodic Acid Schiff’s base (PAS) stain after CG degradation of lubricin and SDS-PAGE separation of the proteolytic products. Recombinant

(rhPRG4) and purified lubricin from SF were incubated for two hours with CG, followed by separation on gels and PAS staining. This general glycostain reacts with the all _O_-glycans present

on lubricin. It visualized the presence of a heavily _O_-glycosylated intact mucin domains shown by the intense staining before CG digestion of rhPRG4 and native lubricin. After digestion

only two faintly stained glycosylated degradation products (15- and 25-kDa) were detected on the SDS-PAGE gels (Fig. 4a), both for rhPRG4 and native lubricin. This indicated that most

glycopeptides generated after incubation remained undetected using SDS-PAGE and that additional proteolytic glycosylated peptides may be present as lower mass. The result supported previous

indication in this report, that both the glycosylated and non-glycosylated regions of lubricin were proteolytically digested by CG. We also then examined CG degradation of the lubricin mucin

domain in SF where the natural SF protease CG inhibitors were shown to be present as described above. Due to presence of many different glycoproteins in SF, the western blot was developed

using peanut agglutinin (PNA) lectin. PNA binds mucin type _O_-glycans (Galβ1–3GalNAc-) that are abundant on lubricin mucin domain10. Using this approach we detected full length lubricin in

SF (Fig. 4A). After two hours of incubation of OA SF with added CG, the intensity of the band corresponding to full length lubricin had decreased considerably compared to the control without

CG, and the formation of a weakly stained band at 25 kDa was observed (Fig. 4b) consistent with previous results. Western blot using PNA of SF proteins incubated without CG revealed that in

addition to full length lubricin, several other PNA reactive components of unknown origin at 50–100 kDa was detected. These components probably represent other PNA reactive proteins in SF

as well as degradation products of lubricin. Using sandwich ELISA we also quantitatively assessed the ability of CG to digest native lubricin present in SF. Eight OA SF samples were

incubated with or without supplement of exogenous CG. Lubricin was quantified using ELISA with mAb 9G3 as the catching antibody and PNA lectin for detection. With this ELISA method, we could

estimate the amounts of lubricin in OA SF to be in the range of 300–550 µg/ml (Fig. 4c). After incubation with CG (8–15 w/w%, enzyme to lubricin weight ratio), the amount of lubricin was

decreased approximately 50% Fig. 3d). AN ENDOGENOUS 25-KDA LUBRICIN FRAGMENT IS FOUND IN SF FROM OA PATIENTS AND IS INCREASED AFTER CG INCUBATION We were interested to investigate if the 25

kDa mucin fragment generated from lubricin also could be found in SF, providing evidence that lubricin is degraded in its natural environment. Indeed, by increasing exposure time of the

western blot using the mucin domain mAb 9G3, a single lubricin fragment at 25 kDa of endogenous origin was observed in SF from 13 OA patients without CG supplementation (Fig. 5a,b and

Supplementary Fig. S5). The selected region from a western blot shows the lubricin degradation fragment at 25 kDa in SF from thirteen patients (Fig. 5a). We could also show that the amount

of the 25 kDa fragment was increased after addition of exogenous CG to SF (Fig. 5c and Supplementary Fig. S7). Degradation of full length lubricin was accompanied by a concomitant increase

of a 25-kDa lubricin fragment, similar as was observed for rhPRG4 (Fig. 3a). We found that extending the incubation of lubricin with CG even for a longer period (>16 hours, results not

shown) eventually decreased the intensity of the 25-kDa fragment. This indicated that CG was capable of digesting this component even further. These experiments suggest that endogenous SF CG

is at least partly responsible for generating the 25-kDa lubricin fragment found in OA patients. PROTEOMICS AND GLYCOPROTEOMICS ANALYSES OF RHPRG4 DIGESTED WITH CG In order to identify CG

cleavage sites within lubricin, rhPRG4 was incubated with CG in PBS overnight at 37 °C at a ratio of 1:45 (enzyme to substrate, by weight), and the obtained degradation products analyzed

with LC-MS/MS. We identified 135 non-glycosylated peptides and 72 glycopeptides in the size range of 6–37 amino acids, the majority from the _N_- and _C_-terminal of lubricin (Supplementary

Tables S1 and S2). CG has been described to have a combination of tryptic and chymotryptic type specificity, but is also reported to cleave at other amino acids40,41,42. An overview of the

cleavage sites in lubricin detected here are displayed in Fig. 6a. As a control experiment, we performed semi-tryptic searches of tryptic digests of rhPRG4, which revealed that 13 peptides

could originate from other sources than CG digestion, for example autoproteolytic degradation. The most frequent CG cleavage site was C-terminal of lysine residues (33%), a site which has

been reported previously for CG40. Many peptides were found to be overlapping within the same regions in the peptide backbone. CG cleavage sites within the glycosylated mucin domain were

identified after manual evaluation of MS spectra. The glycopeptides detected constituted glycoforms made up from 35 lubricin derived peptides, carrying glycans of different monosaccharide

compositions, and consisting of Hex, HexNAc and NeuAc residues, matching simple core 1 type _O_-glycosylation that is produced in CHO cells from where the rhPRG4 was expressed (Supplementary

Table S2). Higher-energy collisional dissociation (HCD) fragmentation did not reveal glycan site specific information, however all but one deduced peptide contained Thr or Ser residues. The

remaining peptide D.MDYLPRVPN.Q from the C-terminal (aa 1122–1130) was detected as two glycoforms and proposed to be _O_-glycosylated on a Tyr residue (Supplementary Fig. S8).

_N-_glycosylation was only found on the peptide L.RNGTVLAF.R (aa 1158–1165) detected as two glycoforms. The monosaccharide compositions revealed _N_-glycans of high mannose type

(Supplementary Fig. S9). We have also detected this potential _N_-glycan site in tryptic digests of intact lubricin(data not shown). Mass spectra of three glycopeptides with the peptide

sequences ‘ETAPTTPK’, ‘KEPAPTTPK’ and ‘KEPAPTTPKKPAPK’ from within the mucin repeat region are shown in Fig. 6c and Supplementary Figs S10 and S11, respectively. These repeat peptides were

found 3, 17, and 2 times respectively in the mucin domain. Together with the identification of two nonglycosylated repeat peptides (‘KEPAPTTPKKPAPK’ and ‘SAPTTTKEPAPTTTK’, Supplementary

Table S1), these data provided mass spectrometric evidence for that CG may cleave within the mucin region. The _N_-terminal derived glycopeptide with the sequence

‘K.DNKKNRTKKKPTPKPPVVDEAG.S’ (aa 202–223) contained two potential glycosylation sites (Thr208 and Thr213) and was detected as two glycoforms. The monosaccharide compositions of the first

glycoform supported the presence of a T-antigen (Galβ1-3GalNAc) and the second glycoform supported the presence of the sialylated T-antigen (Fig. 6b). CG was also able to cleave this

glycopeptide stretch further (Supplementary Table S2). The CG cleavage sites within amino acid sequence 202–223 are summarized by vertical lines: DN|K|K|NRTK|KKPTPKPPVV|D|E|A|G. This example

illustrates that CG can cleave after many different amino acids in lubricin, however at low efficiency. This promiscuity in CG cleavage site specificity has been highlighted in studies with

defined substrates40. DISCUSSION Despite being one of the most common and disabling joint diseases, OA pathogenesis and development are still largely unknown. The success of introducing

recombinant lubricin for OA treatment in animal models43,44, indicates a role of lubricin in OA pathogenesis. To date, improper lubricin post-translational modifications, including

glycosylation profile change39, forming complex with other matrix proteins45, and proteolytic cleavages are all reported in OA. This may ultimately alter the surface lubrication and

contribute to disease development. Here, we investigate the role of serine protease CG, with respect to its presence in OA SF as well as its degrading ability. CG has previously been

suggested to be present in SF of OA-joints, using a colorimetric peptide substrate assay, specific for chymotryptic like proteases37. In this study, we validated the finding of CG in OA by

detecting endogenous CG in SF from 16 patients using western blot (Fig. 2). A complete degradation of rhPRG4, even for the putatively protected mucin domain, was observed after CG

incubation, and this digestion can be enhanced by a prolonged time and increased enzyme levels within physiologically relevant concentrations (Fig. 3a,b and Fig. 4a). These data showed that

CG is an efficient protease capable of degrading lubricin. Inspired by these results we monitored the effect of CG digestion of lubricin from SF from individual OA patients and from an SF

pool from patients with RA. CG was found to readily degrade native lubricin, although at a slightly lower rate compared to rhPRG4 (Figs. 3c, 4a,b and 5c). The findings demonstrate the potent

lubricin degrading ability of CG, both in a purified _in vitro_ incubation system and in a more complex biological environment as in SF from OA patients. From our data we can speculate that

three factors influence the CG degrading efficiency of lubricin: * 1. Differences in glycosylation of the native lubricin variants (OA versus RA)39, and also for rhPRG4, the latter having

CHO cell _O_-glycosylation. * 2. CG degrading efficiency in SF is be affected by other proteins competing with lubricin as CG substrates. * 3. SF serine protease inhibitors preventing CG

activity. The CG digests of both recombinant and native lubricin revealed a glycosylated lubricin degradation product of approximately 25 kDa, which was detected by western blot (using mAb

9G3 or PNA) and with the glycosensitive stain PAS staining (Figs. 3a, 4a,c, and 5c). The presence of glycosylation makes the fragment barely detectable with Coomassie protein stain. Tryptic

digestion/MS analysis of this 25 kDa fragment to reveal its identity, did not generate any peptides or glycopeptides. The reason for this could be due to that CG was shown to display a

promiscuous proteolytic nature, and that the monoclonal lubricin antibody 9G3, binds glycosylated forms of the sequence ‘KEPAPTTT’12, present multiple times in the mucin domain. Both these

facts suggest that the 25 kDa fragment is not made up of a homogenous peptide stretch, making it hard to be identified. Inefficient tryptic digestion of dense and heterogeneous

glycosylation, as well as MS ionization inefficiency of glycopeptides contributed to not being able of displaying the full spectrum of various lubricin glycopeptides constituting the 25 kDa

fragment band. With endogenous CG being present in SF of OA patients, we hypothesized that this protease could generate such a mucin domain containing fragment also _in vivo_. The detection

of an endogenously produced 25 kDa lubricin fragment band with mAb 9G3 in SF from 13 late-stage OA patients (Fig. 5a,b) confirmed that lubricin was indeed degraded partially in OA SF by a CG

like protease. In all, our experiments thus supported that CG could be a protease candidate for proteolytic digestion of lubricin in SF. CG is a neutrophil serine protease, and neutrophils

are the main immune cells found in SF in RA patients SF as an effect of RA associated inflammation. While lubricin degradation in RA was not specifically addressed here, our data suggests

that lubricin degradation and neutrophil degradation may be highly relevant in RA pathology. Our observation that CG is present also in OA patients SF is in consistent with and extends

previous findings that joint inflammation increases during OA and relates to that plasma neutrophil activation can serve as a biomarker of OA46. Our finding is in accordance with previous

knowledge that CG is notably released during inflammatory processes and contributes to ECM degradation35. CG as a traditional immune activator and regulator, was proved to be responsible for

pro-inflammatory IL-1 family cytokines activation in a recent research paper47. Cytokine IL-1β is found to be active during OA and induces inflammatory responses that cause protease

activation and degradation of ECM proteins28,48. Furthermore, decreased amount of lubricin was reported by treating cartilage with IL-1β in animal models21,49. The present study proves a

lubricin degradation ability of CG, which renders CG a potential role during OA, strengthens the importance of further understanding of CG in OA disease and provides the connection between

inflammation and lubricin modifications during the OA pathologic process. CG has been reported to be a promiscuous protease with both chymase and tryptase activity capable of cleaving both

at charged amino acids (eg. Lys and Arg) as well as hydrophobic amino acids (eg Phe, Trp, and Leu)40,42. Proteomics and glycoproteomics of CG digestions of recombinant lubricin proved the

enzyme to be an efficient protease, and gave an explanation for the degradation of lubricin observed in our western blots. We could detect peptides in the size range of 6–37 amino acids from

both the _N_- and _C_-terminal, as well as the mucin domain, proving that CG digested lubricin at numerous sites in the protein backbone. 33% of the identified peptides contained

_C_-terminal Lys residues (Supplementary Table S1 and S2). Hence, the Lys residues which are frequently found throughout the lubricin repeat region in the mucin domain must be obvious

targets for digestion. Lys is the most common amino acid (165 aa of total of 1404) in lubricin after Thr and Pro, the two main constituents of the mucin domain. We detected three

glycopeptide sequences originating from the mucin domain (Supplementary Table S2). Limited peptide coverage within the mucin domain is expected, since glycosylated peptides from the mucin

domain are often more difficult to detect (high heterogeneity, poor ionization efficiency etc). These three glycopeptides occur multiple times in the mucin domain. Together with the

detection of two nonglycosylated peptides from the same region (Supplementary Table S1), they provide ample evidence for that the mucin domain, which with glycosylation has an estimated size

of 250 kDa (Fig. 1), can be degraded into 25-kDa and smaller fragments, as observed with western blot and proteomics. In order to validate some of the lubricin peptides proposed to be

formed by CG digestion in this study, we investigated the presence of ‘_in-vitro_ formed’ autoproteolytic peptides in tryptic digests of recombinant lubricin (rhPRG4). Surprisingly, we did

detect a small number of semitryptic peptides, which indicates that larger tryptic lubricin peptides may be degraded in the test tube to smaller semitryptic peptides that mistakenly can be

assigned as a protease products. One example was the peptide H.VFMPEVTPDMDYLPR.V (aa1113–1127). The non-tryptic cleavage site at aa 1112 has previously been reported to be a cathepsin S

cleavage site in tear fluid21, and equivalent site reported to be an endogenous protease cleavages in SF derived lubricin from horse43. Our data suggests an alternative explanation of

post-proteolysis induced after tryptic digestion. OA is a multifactorial disease, and beyond all doubt there is more than one factor that contributes to OA lubricin modifications. The

present work demonstrates the potency of CG for lubricin degradation, providing the hypothesis that CG is involved and contributes to OA disease development. The involvement of CG as a

neutrophil protease relevant in other arthritic diseases suggest that lubricin and CG degradation studies also would need to be expanded including other joint degrading diseases. The

proteolytic cleavage product identified here has a potential to serve as local or systemic inflammatory biomarker for lubricin degradation. MATERIALS AND METHODS LUBRICIN AND SYNOVIAL FLUID

SAMPLES Synovial fluid (SF) samples were collected from 16 late-stage idiopathic OA patients (8 males and 8 females) subjected to knee replacement surgery. The mean age of the patients was

71 years (range 62–87 years). All individuals gave written consent and the procedure was approved by the ethics committee at Sahlgrenska University Hospital (ethical application 172–15). The

SF samples were collected prior surgery, centrifuged, aliquoted and stored at −80 °C until assayed. Recombinant lubricin (rhPRG4, 1 mg/mL in Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS) + 0.1% Tween 20)

was obtained from Lubris BioPharma, USA. CG (22 ng/μL in PBS) was isolated from human leukocytes (Sigma-Aldrich, Germany). Purified native lubricin (SF Lub) was enriched from patients’

synovial fluid (pooled from RA patients, n = 10) by anion exchange chromatography and ethanol precipitation as described elsewhere50, and was quantified using lubricin sandwich ELISA as

described below. _IN VITRO_ DIGESTION OF LUBRICIN BY CG rhPRG4 and lubricin purified from SF, 2–5 μg, were incubated with different concentrations (2.5–125 ng) of CG in at 37 °C in PBS (pH

7.4) for 30 minutes, 2 hours or over-night (16 hours). SF (2–2.5 μL) were incubated with CG (22–44 ng) in 37 °C for 1 or 2 hours, or a time series of 30 min and 16 hours (specific digestion

conditions are indicated in figures). For positive control, CG activity was assessed using a fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET) substrate (Abz-EPFWEDQ-EDDnp)51. The assay was

performed at 37 °C by mixing CG (10 nM, 25 µL) to the fluorescent substrate (20 µM, 25 µL). The reaction was buffered with 100 nM NaCl, 0.01 vol% Igepal CA-630 at pH 7.452. Measurement of

the increase in fluorescence was performed in regular intervals (Δt = 2 mins) and the plate was shaken regularly during the experiment. The results shown in Supplementary Fig S11. SDS-PAGE

Purified native lubricin and SF samples from CG incubations, and also SF samples (16 OA patient samples, 2 μl SF) used for screening of endogenous CG or lubricin degradation fragments, were

reduced with 50 mM dithiothreitol (DTT) (Merck KGaA) followed by boiling at 95 °C for 15 minutes, and alkylation by 125 mM iodoacetamide (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, US) in dark for 45

minutes. Samples were analysed on NuPAGE Tris-acetate 3–8% gel (Invitrogen, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, US). One μg of rhPRG4 or 22 ng CG (for endogenous CG assay) were included

on each gel as controls. Molecular weight was compared to PageRuler Plus Prestained Protein Ladder (10 to 250 kDa, Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA). Gels were stained either with Coomassie

brilliant blue R-250 (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA, US) or with Periodic Acid-Schiff (PAS) (Sigma-Aldrich) according to the manufacturers’ instructions. Lubricin band intensities were

plotted and peak values were calculated by ImageJ (ImageJ 1.50i, USA)53. WESTERN BLOT ANTIBODY AND LECTIN STAINING After electrophoresis, the gels were blotted to an Immobilon-P PVDF

Membrane (Merck Millipore, Burlington, MA, US) using Trans-Blot SD Semi-Dry Transfer Cell (Bio-Rad Laboratories) at 200 mA for 80 minutes. After blocking with 1% bovine serum albumin (BSA)

(VWR, Radnor, PA, US), the membranes were probed with 1 μg/mL mAb 9G3 against the glycosylated epitope ‘KEPAPTTT’ in the lubricin mucin domain (Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany12) or

polyclonal anti-CG antibody (Abcam, UK) 1/1000 diluted in assay buffer (1% BSA in PBS-Tween) for detection of endogenous CG in SF, followed by Horseradish Peroxidase (HRP) conjugated goat

anti-mouse IgG (H + L) highly cross-adsorbed secondary antibody (Invitrogen, USA) 1/4000 diluted in assay buffer. For the lectin staining assay, blots were first probed by 1 μg/ml

biotinylated Peanut Agglutinin (PNA, Vector laboratories, CA,USA) followed by 0.2 μg/ml HRP-streptavidin (Vector laboratories). After incubations, membranes were stained by WesternBright ECL

Spray (Advansta, USA) and visualized in a luminescent image analyser (LAS-4000 mini, Fujifilm, Japan). Band intensities were calculated by ImageJ 1.50i53. LUBRICIN SANDWICH ELISA An

in-house ELISA method was set-up and validated for measuring lubricin concentrations in SF, adapted from others54,55. Monoclonal antibody 9G3 (1 μg/mL in PBS) was coated on 96-well

Nunc-Immuno maxisorp plates (Thermo Fisher Scientific) at 4 °C over-night. After blocking with 3% BSA in PBS + 0.05% Tween, SF samples were added as a dilution series (1/50) in assay buffer

(1% BSA in PBS-Tween) and incubated for 1 hour at room temperature (RT). Bound proteins were then incubated with biotinylated PNA (Vector laboratories) (1 μg/mL, 1 hour at RT), followed by

HRP-streptavidin (Vector laboratories) at 0.1 μg/mL (1 hour at RT). Between each incubation, the wells were washed three times with PBS-Tween to remove unbound reagents. Proteins were

stained with 1-Step Ultra TMB-ELISA Substrate Solution (Thermo Fisher Scientific) until blue colour was fully generated and the reaction stopped by adding 1 M H2SO4. Absorbances were read at

450 nm, and compared with a standard curve using recombinant lubricin (dilution series of rhPRG4 (1 mg/mL) in assay buffer). Samples were measured in duplicates and mean values are

reported. The lubricin ELISA had an intra plate CV = 7.5% (n = 1 SF sample with 10 repeats) and a inter plate CV% = 7.8% (n = 1 SF sample, tested on 4 plates). Technical performance of the

assay is summarized in Supplementary Table 3. LC-MS/MS AND MS DATA ANALYSES rhPRG4 (10 μg in 10 μl PBS + 0.1% Tween 20) was incubated with CG (0.22 μg in 10 μL) in 37 °C under non-reducing

conditions over night. Technical incubations experiments and MS analyses were performed in duplicates, with or without subsequent Tween removal (Pierce Detergent Removal Spin Column 125 μL,

Thermo Fisher Scientific), where the latter approach was found be generating fewer detected peptides. The results reported (Supplementary Tables S1 and S2) are the combined result. For

control experiments and semitryptic searches, rhPRG4 was digested with trypsin in-solution or in-gel as described elsewhere56. The peptides were desalted using C18 ziptips, followed by

separation with LC-MS using in-house packed C18 columns at a flow rate of 200 nL/min, and a 45-min gradient of 5–40% buffer B (A: 0.1% formic acid, B:0.1% formic acid, 80% acetonitrile). The

column was connected to an Easy-nLC 1000 system (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Odense, Denmark), a nano-electrospray ion source and a Q-Exactive Hybrid Quadrupole-Orbitrap Mass Spectrometer

(Thermo Fisher Scientific). For full scan MS, the instrument was scanned _m/z_ 350–2000, resolution 60000 (_m/z_ 200), AGC target 3e6, max IT 20 ms, dynamic exclusion 10 sec. The twelve most

intense peaks (charge states 2, 3, 4) were selected for fragmentation with higher-energy collisional dissociation (HCD). For MS/MS, resolution was set to 15000 (_m/z_ 200), AGC target to

5e5, max IT 40 ms, and collision energy NCE = 27%. Raw data files were searched against the human Uniprot protein database (downloaded 17.11.2017) using Peaks Studio 8.5 (Bioinformatics

Solutions Inc., Waterloo, Canada). For peptide identification, mass precursor error tolerance was set to 5 ppm, and fragment mass error tolerance to 0.03 Da, enzyme: none; variable

modifications: oxidation (M) and deamidation (NQ). Peptide-spectrum matches were filtered to 0.1% false discovery rate (Peaks peptide score > 25). Glycopeptide MS-MS spectra were selected

with Peaks Studio software and/or manually using glycan diagnostic ions in the lower mass range (_m/z_ 186, 204, 274, 292, 366). Spectra were evaluated manually, all major fragment ions

were assigned and >4 b/y ions required in order to identify the peptide backbone. The assignments were aided by proteomics mining tools available free of charge (Findpept and PeptideMass

(web.expasy.org); MS-product (Protein Prospector http://prospector.ucsf.edu). Mass precursor errors were less than 5 ppm. STATISTICS All statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad

Prism 8 for MacOS (GraphPad Software, San Diego, California USA, www.graphpad.com). Statistical difference was calculated by two-tailed Mann Whitney test or ordinary two-way ANOVA with

Holm-Sidak’s multiple comparison. ETHICAL APPROVAL All OA and RA patients gave informed consent and all the procedures were approved by the regional ethical review board in Gothenburg

(172-15,13/5-2015). The study conformed to the ethical guidelines of the 1975 Declaration of Helsinki of research involving human subjects. All methods were performed in accordance with the

relevant guidelines and regulations. CHANGE HISTORY * _ 15 FEBRUARY 2021 A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-77619-5 _ REFERENCES * Jay, G. D.

_et al_. Association between friction and wear in diarthrodial joints lacking lubricin. _Arthritis Rheum._ 56, 3662–3669, https://doi.org/10.1002/art.22974 (2007). Article CAS PubMed

PubMed Central Google Scholar * Marcelino, J. _et al_. CACP, encoding a secreted proteoglycan, is mutated in camptodactyly-arthropathy-coxa vara-pericarditis syndrome. _Nat. Genet._ 23,

319–322 (1999). Article CAS Google Scholar * Wong, B. L., Kim, S. H., Antonacci, J. M., McIlwraith, C. W. & Sah, R. L. Cartilage shear dynamics during tibio-femoral articulation:

effect of acute joint injury and tribosupplementation on synovial fluid lubrication. _Osteoarthr. Cartil._ 18, 464–471, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joca.2009.11.008 (2010). Article CAS

Google Scholar * Waller, K. A. _et al_. Role of lubricin and boundary lubrication in the prevention of chondrocyte apoptosis. _Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA_ 110, 5852–5857,

https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1219289110 (2013). Article CAS PubMed ADS Google Scholar * D’Lima, D. D., Hashimoto, S., Chen, P. C., Colwell, C. W. Jr. & Lotz, M. K. Human chondrocyte

apoptosis in response to mechanical injury. _Osteoarthr. Cartil._ 9, 712–719, https://doi.org/10.1053/joca.2001.0468 (2001). Article Google Scholar * Abubacker, S. _et al_. Absence of

proteoglycan 4 (Prg4) leads to increased subchondral bone porosity which can be mitigated through intra-articular injection of PRG4. _J. Orthop. Res._ https://doi.org/10.1002/jor.24378

(2019). Article PubMed Google Scholar * Flannery, C. R. _et al_. Articular cartilage superficial zone protein (SZP) is homologous to megakaryocyte stimulating factor precursor and Is a

multifunctional proteoglycan with potential growth-promoting, cytoprotective, and lubricating properties in cartilage metabolism. _Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun._ 254, 535–541,

https://doi.org/10.1006/bbrc.1998.0104 (1999). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Jay, G. D., Tantravahi, U., Britt, D. E., Barrach, H. J. & Cha, C. J. Homology of lubricin and

superficial zone protein (SZP): products of megakaryocyte stimulating factor (MSF) gene expression by human synovial fibroblasts and articular chondrocytes localized to chromosome 1q25. _J.

Orthop. Res._ 19, 677–687, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0736-0266(00)00040-1 (2001). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Lee, S. Y., Nakagawa, T. & Reddi, A. H. Induction of

chondrogenesis and expression of superficial zone protein (SZP)/lubricin by mesenchymal progenitors in the infrapatellar fat pad of the knee joint treated with TGF-beta1 and BMP-7. _Biochem.

Biophys. Res. Commun._ 376, 148–153, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbrc.2008.08.138 (2008). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Jay, G. D., Harris, D. A. & Cha, C. J. Boundary

lubrication by lubricin is mediated by O-linked beta(1-3)Gal-GalNAc oligosaccharides. _Glycoconj. J._ 18, 807–815, https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1021159619373 (2001). Article CAS PubMed

Google Scholar * Jay, G. D. & Waller, K. A. The biology of lubricin: near frictionless joint motion. _Matrix Biol._ 39, 17–24, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matbio.2014.08.008 (2014).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Ai, M. _et al_. Anti-Lubricin Monoclonal Antibodies Created Using Lubricin-Knockout Mice Immunodetect Lubricin in Several Species and in Patients with

Healthy and Diseased Joints. _Plos One_ 10, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0116237 (2015). * Swann, D. A., Silver, F. H., Slayter, H. S., Stafford, W. & Shore, E. The molecular

structure and lubricating activity of lubricin isolated from bovine and human synovial fluids. _Biochem. J._ 225, 195–201 (1985). Article CAS Google Scholar * Jay, G. D. Characterization

of a bovine synovial fluid lubricating factor. I. Chemical, surface activity and lubricating properties. _Connect. Tissue Res._ 28, 71–88 (1992). Article CAS Google Scholar * Deng, G.,

Curriden, S. A., Hu, G., Czekay, R. P. & Loskutoff, D. J. Plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 regulates cell adhesion by binding to the somatomedin B domain of vitronectin. _J. Cell

Physiol._ 189, 23–33, https://doi.org/10.1002/jcp.1133 (2001). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Piccard, H., Van den Steen, P. E. & Opdenakker, G. Hemopexin domains as

multifunctional liganding modules in matrix metalloproteinases and other proteins. _J. Leukoc. Biol._ 81, 870–892, https://doi.org/10.1189/jlb.1006629 (2007). Article CAS PubMed Google

Scholar * Jay, G. D. _et al_. Lubricating ability of aspirated synovial fluid from emergency department patients with knee joint synovitis. _J. Rheumatol._ 31, 557–564 (2004). PubMed

Google Scholar * Schmidt, T. A., Schumacher, B. L., Klein, T. J., Voegtline, M. S. & Sah, R. L. Synthesis of proteoglycan 4 by chondrocyte subpopulations in cartilage explants,

monolayer cultures, and resurfaced cartilage cultures. _Arthritis Rheum._ 50, 2849–2857, https://doi.org/10.1002/art.20480 (2004). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Elsaid, K. A., Jay,

G. D., Warman, M. L., Rhee, D. K. & Chichester, C. O. Association of articular cartilage degradation and loss of boundary-lubricating ability of synovial fluid following injury and

inflammatory arthritis. _Arthritis Rheum._ 52, 1746–1755, https://doi.org/10.1002/art.21038 (2005). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Young, A. A. _et al_. Proteoglycan 4

downregulation in a sheep meniscectomy model of early osteoarthritis. _Arthritis Res. Ther._ 8, R41, https://doi.org/10.1186/ar1898 (2006). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google

Scholar * Elsaid, K. A., Jay, G. D. & Chichester, C. O. Reduced expression and proteolytic susceptibility of lubricin/superficial zone protein may explain early elevation in the

coefficient of friction in the joints of rats with antigen-induced arthritis. _Arthritis Rheum._ 56, 108–116, https://doi.org/10.1002/art.22321 (2007). Article PubMed Google Scholar *

Musumeci, G. _et al_. Lubricin expression in human osteoarthritic knee meniscus and synovial fluid: a morphological, immunohistochemical and biochemical study. _Acta Histochem._ 116,

965–972, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acthis.2014.03.011 (2014). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Vos, T. _et al_. Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived

with disability for 310 diseases and injuries, 1990-2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015. _Lancet_ 388, 1545–1602,

https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31678-6 (2016). Article Google Scholar * Lee, A. S. _et al_. A current review of molecular mechanisms regarding osteoarthritis and pain. _Gene_ 527,

440–447, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gene.2013.05.069 (2013). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Robinson, W. H. _et al_. Low-grade inflammation as a key mediator of the

pathogenesis of osteoarthritis. _Nat. reviews. Rheumatol._ 12, 580–592, https://doi.org/10.1038/nrrheum.2016.136 (2016). Article CAS Google Scholar * Morris, E. A., McDonald, B. S., Webb,

A. C. & Rosenwasser, L. J. Identification of interleukin-1 in equine osteoarthritic joint effusions. _Am. J. Vet. Res._ 51, 59–64 (1990). CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Alwan, W. H. _et

al_. Interleukin-1-like activity in synovial fluids and sera of horses with arthritis. _Res. Vet. Sci._ 51, 72–77 (1991). Article CAS Google Scholar * Goldring, M. B. Anticytokine

therapy for osteoarthritis. _Expert. Opin. Biol. Ther._ 1, 817–829, https://doi.org/10.1517/14712598.1.5.817 (2001). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Kamm, J. L., Nixon, A. J. &

Witte, T. H. Cytokine and catabolic enzyme expression in synovium, synovial fluid and articular cartilage of naturally osteoarthritic equine carpi. _Equine Vet. J._ 42, 693–699,

https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2042-3306.2010.00140.x (2010). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Regmi, S. C. _et al_. Degradation of proteoglycan 4/lubricin by cathepsin S:

Potential mechanism for diminished ocular surface lubrication in Sjogren’s syndrome. _Exp. Eye Res._ 161, 1–9, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.exer.2017.05.006 (2017). Article CAS PubMed Google

Scholar * Senior, R. M. _et al_. Elastase of U-937 monocytelike cells. Comparisons with elastases derived from human monocytes and neutrophils and murine macrophagelike cells. _J. Clin.

Invest._ 69, 384–393 (1982). Article CAS Google Scholar * Campbell, E. J., Silverman, E. K. & Campbell, M. A. Elastase and cathepsin G of human monocytes. Quantification of cellular

content, release in response to stimuli, and heterogeneity in elastase-mediated proteolytic activity. _J. Immunol._ 143, 2961–2968 (1989). CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Burster, T. _et al_.

roles in antigen presentation and beyond. _Mol. Immunol._ 47, 658–665, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molimm.2009.10.003 (2010). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Milosev, I., Levasic, V.,

Vidmar, J., Kovac, S. & Trebse, R. pH and metal concentration of synovial fluid of osteoarthritic joints and joints with metal replacements. _J. Biomed. Mater. Res. B Appl. Biomater._

105, 2507–2515, https://doi.org/10.1002/jbm.b.33793 (2017). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Wiedow, O. & Meyer-Hoffert, U. Neutrophil serine proteases: potential key regulators

of cell signalling during inflammation. _J. Intern. Med._ 257, 319–328, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2796.2005.01476.x (2005). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Korkmaz, B., Horwitz,

M. S., Jenne, D. E. & Gauthier, F. Neutrophil Elastase, Proteinase 3, and Cathepsin G as Therapeutic Targets in Human Diseases. _Pharmacol. Rev._ 62, 726–759,

https://doi.org/10.1124/pr.110.002733 (2010). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Miyata, J. _et al_. Cathepsin G: the significance in rheumatoid arthritis as a monocyte

chemoattractant. _Rheumatol. Int._ 27, 375–382, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00296-006-0210-8 (2007). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Takagi, M. _et al_. Cathepsin G and alpha

1-antichymotrypsin in the local host reaction to loosening of total hip prostheses. _J. Bone Jt. Surg. Am._ 77, 16–25, https://doi.org/10.2106/00004623-199501000-00003 (1995). Article CAS

Google Scholar * Estrella, R. P., Whitelock, J. M., Packer, N. H. & Karlsson, N. G. The glycosylation of human synovial lubricin: implications for its role in inflammation. _Biochem.

J._ 429, 359–367, https://doi.org/10.1042/BJ20100360 (2010). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Thorpe, M. _et al_. Extended cleavage specificity of human neutrophil cathepsin G: A low

activity protease with dual chymase and tryptase-type specificities. _PLoS One_ 13, e0195077, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0195077 (2018). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central

Google Scholar * Nguyen, M. T. N., Shema, G., Zahedi, R. P. & Verhelst, S. H. L. Protease Specificity Profiling in a Pipet Tip Using “Charge-Synchronized” Proteome-Derived Peptide

Libraries. _J. Proteome Res._ 17, 1923–1933, https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jproteome.8b00004 (2018). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * O’Donoghue, A. J. _et al_. Global substrate

profiling of proteases in human neutrophil extracellular traps reveals consensus motif predominantly contributed by elastase. _PLoS One_ 8, e75141,

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0075141 (2013). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central ADS Google Scholar * Flannery, C. R. _et al_. Prevention of cartilage degeneration in a rat model

of osteoarthritis by intraarticular treatment with recombinant lubricin. _Arthritis Rheum._ 60, 840–847, https://doi.org/10.1002/art.24304 (2009). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar *

Waller, K. A. _et al_. Intra-articular Recombinant Human Proteoglycan 4 Mitigates Cartilage Damage After Destabilization of the Medial Meniscus in the Yucatan Minipig. _Am. J. sports Med._

45, 1512–1521, https://doi.org/10.1177/0363546516686965 (2017). Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Flowers, S. A. _et al_. Lubricin binds cartilage proteins, cartilage

oligomeric matrix protein, fibronectin and collagen II at the cartilage surface. _Sci Rep-Uk_ 7, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-13558-y (2017). * Tasoglu, O., Boluk, H., Sahin Onat, S.,

Tasoglu, I. & Ozgirgin, N. Is blood neutrophil-lymphocyte ratio an independent predictor of knee osteoarthritis severity? _Clin. Rheumatol._ 35, 1579–1583,

https://doi.org/10.1007/s10067-016-3170-8 (2016). Article PubMed Google Scholar * Henry, C. M. _et al_. Neutrophil-Derived Proteases Escalate Inflammation through Activation of IL-36

Family Cytokines. _Cell Rep._ 14, 708–722, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.celrep.2015.12.072 (2016). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Lianxu, C., Hongti, J. & Changlong, Y.

NF-kappaBp65-specific siRNA inhibits expression of genes of COX-2, NOS-2 and MMP-9 in rat IL-1beta-induced and TNF-alpha-induced chondrocytes. _Osteoarthr. Cartil._ 14, 367–376,

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joca.2005.10.009 (2006). Article CAS Google Scholar * Svala, E. _et al_. Characterisation of lubricin in synovial fluid from horses with osteoarthritis. _Equine

Vet. J._ 49, 116–123, https://doi.org/10.1111/evj.12521 (2017). Article CAS PubMed ADS Google Scholar * Jin, C. _et al_. Human synovial lubricin expresses sialyl Lewis x determinant and

has L-selectin ligand activity. _J. Biol. Chem._ 287, 35922–35933, https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.M112.363119 (2012). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Korkmaz, B. _et

al_. Measuring elastase, proteinase 3 and cathepsin G activities at the surface of human neutrophils with fluorescence resonance energy transfer substrates. _Nat. Protoc._ 3, 991–1000,

https://doi.org/10.1038/nprot.2008.63 (2008). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Attucci, S. _et al_. Measurement of free and membrane-bound cathepsin G in human neutrophils using new

sensitive fluorogenic substrates. _Biochem. J._ 366, 965–970, https://doi.org/10.1042/bj20020321 (2002). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Schneider, C. A., Rasband, W.

S. & Eliceiri, K. W. NIH Image to ImageJ: 25 years of image analysis. _Nat. Methods_ 9, 671–675 (2012). Article CAS Google Scholar * Elsaid, K. A., Machan, J. T., Waller, K.,

Fleming, B. C. & Jay, G. D. The impact of anterior cruciate ligament injury on lubricin metabolism and the effect of inhibiting tumor necrosis factor alpha on chondroprotection in an

animal model. _Arthritis Rheum._ 60, 2997–3006, https://doi.org/10.1002/art.24800 (2009). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Ludwig, T. E., McAllister, J. R., Lun, V.,

Wiley, J. P. & Schmidt, T. A. Diminished cartilage-lubricating ability of human osteoarthritic synovial fluid deficient in proteoglycan 4: Restoration through proteoglycan 4

supplementation. _Arthritis Rheum._ 64, 3963–3971, https://doi.org/10.1002/art.34674 (2012). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Ali, L. _et al_. The O-glycomap of lubricin, a novel

mucin responsible for joint lubrication, identified by site-specific glycopeptide analysis. _Mol. Cell Proteom._ 13, 3396–3409, https://doi.org/10.1074/mcp.M114.040865 (2014). Article CAS

Google Scholar * Varki, A. _et al_. Symbol Nomenclature for Graphical Representations of Glycans. _Glycobiol._ 25, 1323–1324, https://doi.org/10.1093/glycob/cwv091 (2015). Article CAS

Google Scholar Download references ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This study was funded by grants for the Swedish state under the agreement between the Swedish government and the county council, the

ALF-agreement (ALFGBG-722391), the Swedish Research Council (621-2013-5895), Kung Gustav V:s 80-års foundation, Petrus and Augusta Hedlund’s foundation (M-2016-0353), AFA insurance research

fund (dnr 150150) and IngaBritt and Arne Lundberg Foundation. Sofia Grindberg and Paula-Therese Kelly Pettersson at Danderyd’s Hospital and Lotta Falkendahl at University of Gothenburg are

acknowledged for their assistance in collecting samples. Lubris BioPharma, LLC are acknowledged for providing rhPRG4. Prof Johan Bylund and Felix Klose at the Institute of Odontology,

University of Gothenburg, are acknowledge for technical assistance in evaluating CG activity. Open access funding provided by University of Gothenburg. AUTHOR INFORMATION Author notes *

These authors contributed equally: Shan Huang and Kristina A. Thomsson. * These authors jointly supervised this work: Niclas G. Karlsson and Thomas Eisler. AUTHORS AND AFFILIATIONS *

Department of Medical Biochemistry and Cell Biology, Institute of Biomedicine, Sahlgrenska Academy, University of Gothenburg, Gothenburg, Sweden Shan Huang, Kristina A. Thomsson, Chunsheng

Jin, Sally Alweddi & Niclas G. Karlsson * Science for Life Laboratory, Department of Oncology-Pathology, Clinical Proteomics Mass Spectrometry, Karolinska Institutet, Solna, Sweden

Chunsheng Jin * Department of Clinical Sciences Lund, Orthopaedics, Faculty of Medicine, Lund University, Lund, Sweden André Struglics * Department of Orthopaedics, Institute of Clinical

Sciences, The Sahlgrenska Academy, University of Gothenburg, Gothenburg, Sweden Ola Rolfson * Department of Rheumatology and Inflammation Research, Institute of Medicine, Sahlgrenska

Academy, University of Gothenburg, Gothenburg, Sweden Lena I. Björkman * Department of Molecular Skeletal Biology, Lund University, Lund, Sweden Sebastian Kalamajski * Biomedical Engineering

Department, University of Connecticut Health Centre, Farmington, CT, USA Tannin A. Schmidt * Department of Emergency Medicine, Warren Alpert Medical School and Division of Biomedical

Engineering, School of Engineering, Brown University, Providence, RI, USA Gregory D. Jay * Cell Biology and Anatomy, Cumming School of Medicine, University of Calgary, 3330 Hospital Drive

NW, Calgary, Alberta, T2N4N1, Canada Roman Krawetz * McCaig institute for Bone and Joint Health, University of Calgary, Calgary, Alberta, T2N4N1, Canada Roman Krawetz * Department of

Clinical Sciences, Danderyd Hospital, Karolinska Institutet, Stockholm, Sweden Thomas Eisler Authors * Shan Huang View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google

Scholar * Kristina A. Thomsson View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Chunsheng Jin View author publications You can also search for this

author inPubMed Google Scholar * Sally Alweddi View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * André Struglics View author publications You can also

search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Ola Rolfson View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Lena I. Björkman View author publications

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Sebastian Kalamajski View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Tannin A. Schmidt

View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Gregory D. Jay View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar *

Roman Krawetz View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Niclas G. Karlsson View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed

Google Scholar * Thomas Eisler View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar CONTRIBUTIONS A.S. and S.K. suggested the idea and performed initial

investigation of lubricin digestion; S.H., S.A. and K.A.T. performed the CG experiments and analysed the data; C.J. purified patient lubricin; T.A.S. and G.D.J. provided rhPRG4; L.I.B.,

O.R., R.K. and T.E. provided patient material. S.H., K.A.T. and N.G.K. wrote the initial manuscript draft; K.A.T., N.G.K. and T.E. updated the manuscript. All authors discussed the results,

commented, and approved the final manuscript. CORRESPONDING AUTHOR Correspondence to Niclas G. Karlsson. ETHICS DECLARATIONS COMPETING INTERESTS G.D.J., R.K. and T.A.S. authored patents

related to rhPRG4 and hold equity in Lubris BioPharma, LLC. TAS is also a paid consultant for Lubris BioPharma, LLC. S.K., C.J. and N.G.K. authored a patent using lubricin for diagnostics.

S.H., K.A.T., S.A. A.S., O.R., L.I.B., R.K. and T.E. declare no competing interest. ADDITIONAL INFORMATION PUBLISHER’S NOTE Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional

claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION. SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION 2. SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION 3. SUPPLEMENTARY

INFORMATION 4. RIGHTS AND PERMISSIONS OPEN ACCESS This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation,

distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and

indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to

the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will

need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. Reprints and permissions ABOUT THIS ARTICLE

CITE THIS ARTICLE Huang, S., Thomsson, K.A., Jin, C. _et al._ Cathepsin g Degrades Both Glycosylated and Unglycosylated Regions of Lubricin, a Synovial Mucin. _Sci Rep_ 10, 4215 (2020).

https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-61161-5 Download citation * Received: 21 August 2019 * Accepted: 20 February 2020 * Published: 06 March 2020 * DOI:

https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-61161-5 SHARE THIS ARTICLE Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content: Get shareable link Sorry, a shareable link is not

currently available for this article. Copy to clipboard Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative