A novel nomogram model for differentiating kawasaki disease from sepsis

- Select a language for the TTS:

- UK English Female

- UK English Male

- US English Female

- US English Male

- Australian Female

- Australian Male

- Language selected: (auto detect) - EN

Play all audios:

ABSTRACT Kawasaki disease (KD) is a form of systemic vasculitis that occurs in children under the age of 5 years old. Due to prolonged fever and elevated inflammatory markers that are found

in both KD and sepsis, the treatment approach differs for each. We enrolled a total of 420 children (227 KD and 193 sepsis) in this study. Logistic regression and a nomogram model were used

to analyze the laboratory markers. We randomly selected 247 children as the training modeling group and 173 as the validation group. After completing a logistic regression analysis, white

blood cell (WBC), anemia, procalcitonin (PCT), C-reactive protein (CRP), albumin, and alanine transaminase (ALT) demonstrated a significant difference in differentiating KD from sepsis. The

patients were scored according to the nomogram, and patients with scores greater than 175 were placed in the high-risk KD group. The area under the curve of the receiver operating

characteristic curve (ROC curve) of the modeling group was 0.873, sensitivity was 0.893, and specificity was 0.746, and the ROC curve in the validation group was 0.831, sensitivity was

0.709, and specificity was 0.795. A novel nomogram prediction model may help clinicians differentiate KD from sepsis with high accuracy. SIMILAR CONTENT BEING VIEWED BY OTHERS A MACHINE

LEARNING MODEL FOR DISTINGUISHING KAWASAKI DISEASE FROM SEPSIS Article Open access 02 August 2023 AN INTERPRETABLE MACHINE LEARNING-ASSISTED DIAGNOSTIC MODEL FOR KAWASAKI DISEASE IN CHILDREN

Article Open access 07 March 2025 THE ASSOCIATION OF SERUM CHI3L1 LEVELS WITH THE PRESENCE OF KAWASAKI DISEASE Article Open access 05 March 2025 INTRODUCTION Kawasaki disease (KD), also

known as cutaneous mucosal lymph node syndrome, is an acute, self-limiting vasculitis that is common in children under the age of 5 years old, with coronary aneurysms occurring in about 25%

of untreated cases. KD has also become the main cause of acquired heart disease in children1,2. Early and timely diagnosis, as well as effective treatment, can help reduce coronary artery

lesions (CAL) and improve intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) treatment response3,4. However, both the etiology and pathogenesis of KD remain unclear. Incomplete KD and Kawasaki disease shock

syndrome (KDSS) are at a high risk of delayed diagnosis and heart complications. In clinical practice, incomplete KD and KDSS are often misdiagnosed as sepsis or septic shock initially, thus

increasing the difficulty in making a KD diagnosis, as well as CAL complications5,6. The differential diagnosis of KD and sepsis in the early stage of onset is challenging. Sepsis is a

systemic inflammatory response syndrome caused by infection, which is also an important cause of septic shock and multiple organ dysfunction syndromes (MODS)7. The main manifestations and

laboratory findings of sepsis include fever, elevated white blood cell count (WBC), C-reactive protein (CRP), and procalcitonin (PCT), which are also the manifestations found in KD8.

Although the early clinical manifestations and laboratory results of sepsis are similar to KD, their clinical treatments differ substantially. Patients with sepsis need timely and

appropriate antimicrobial treatment to control and remove the source of infection9. In contrast, antibiotics are unnecessary and ineffective for KD patients, while IVIG infusion with

follow-up cardiac ultrasonography are the main treatment methods for KD2. Both KD and sepsis are characterized by fever and elevated inflammatory markers in the acute stage, but the

treatments are very different. However, from information evident in previous literature reviews, no relevant or single indicator can differentiate KD from sepsis. Therefore, we conducted a

retrospective analysis of patients' medical records to set up a single or multiple index equation for clinicians in early KD evaluation to prevent cardiac injury. RESULTS We enrolled a

total of 420 children (mean age: 24.4 ± 18.4 months) in this study, including 254 males (60.5%), 166 females (39.5%), 227 KD patients (54.0%), and 193 sepsis patients (46.0%). According to

univariate analysis, we observed no statistically significant differences regarding gender, age, and body weight, as shown in Table 1. The KD group demonstrated statistically significant

higher levels of ALT, AST, platelets, and erythrocyte sedimentation rates (ESR) than the sepsis group (p < 0.05), while the KD group had significantly lower levels of PCT, hemoglobin,

albumin, WBC, and CRP than the sepsis group, as shown in Table 1 (p < 0.05). SELECTED MODEL FACTORS Of those patients, 247 (60%) cases were in the modeling group, including 133 cases of

KD (53.8%) and 114 cases of sepsis, and 173 (40%) cases were in the validation group, including 94 cases of KD (54.3%) and 79 cases of sepsis. We conducted multivariate logistic regression

analysis for the modeling group. Logistic regression analysis was carried out using the statistically significant factors in the univariate analysis as independent variables. The p-value of

the Hosmer and Lemeshow test in this model was 0.32. After the multiple logistic regression analysis of the cut-off values, we found WBC, hemoglobin, PCT, CRP, ALB, and ALT to be the

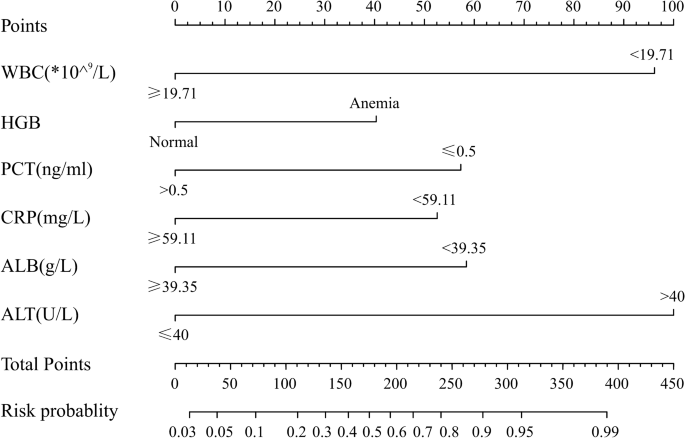

independent risk factors of KD (Table 2). PREDICTIVE NOMOGRAM TO DIFFERENTIATE KD FROM SEPSIS According to the results of the multivariate logistics regression analysis, we used WBC, anemia,

PCT, CRP, albumin, and ALT to develop the nomogram model (Fig. 1). In the nomogram, ALT was the largest predictor for KD (100 points), followed by WBC (96 points), PCT (57 points), CRP (53

points), and albumin (58 points), while anemia was the smallest predictor (40 points). The total score was 404 points. The incidence of KD corresponding to the score values is shown in Table

3. We use a 50% probability as the classification cutoff value, corresponding to 175 points. In this prediction model, if the patient score is higher than 175 (with a KD probability of more

than 50%), while we predict that patient scores of 175 or less may be sepsis, with a probability of more than 50%. PERFORMANCE OF THE NOMOGRAM We evaluated performance of the nomogram using

discrimination and calibration10. Based on the receiver operating characteristic curve (ROC curve) analysis, the nomogram demonstrated good discrimination ability, with an area under the

ROC curve of 0.873 (95% confidence interval 0.829–0.918) in the modeling group and 0.831 (95% confidence interval 0.769–0.0.892) in the validation group. The sensitivity and specificity were

0.893 and 0.746, respectively, in the modeling group and 0.709 and 0.795, respectively, in the validation group. Calibration curves of the nomogram for the two groups are shown in Figs. 2

and 3, which demonstrated no apparent fit, with good correspondence between predicted outcome and actual outcome. DISCUSSION KD is currently diagnosed primarily according to clinical

manifestations, but no specific laboratory method is available for diagnosis. Furthermore, the diagnosis of incomplete KD is also difficult and increases delayed diagnosis. Although the

clinical manifestations and laboratory findings of KD and sepsis differ, some overlap has still been noted. In particular, incomplete KD and KDSS make differentiating the diagnosis from

sepsis difficult in clinical practice. The purpose of this study is to compare laboratory findings in KD and sepsis to provide specific characteristics that can help clinicians detect KD

earlier. In this study, compared to the sepsis group, the KD group showed a significant decrease in albumin. Children with KD are often associated with hypoalbuminemia, a pathogenesis that

has many explanations. Previous research has reported that the albumin level of KD was significantly lower than that of the febrile control group11, indicating that the decrease of albumin

may be related to the increase of vascular permeability. Said increase in vascular permeability may be caused by the increased movement of albumin from the blood vessels to the interspaces

mediated by hormones, innervations, or cytokines (especially IL-2, interferon-alpha, and IL-6)12. Kuo et al. reported that the lower the albumin level, the higher the rate of CAL formation

in KD13. Anemia is one of the most common clinical features of KD and is considered to be a marker of the acute phase and disease outcome14. In one retrospective study, hemoglobin level was

found to be the most important indicator for distinguishing KD from the febrile control group15. Furthermore, Lin et al. found that hemoglobin is a useful clinical indicator to distinguish

KDSS from toxic shock syndrome (TSS)4. Recently, Kuo et al. reported that inflammation-induced down-regulation of hepcidin is associated with anemia in KDSS patients16. In our study, the

hemoglobin level of the KD patients was significantly lower than that of the sepsis patients. From previous literature reviews, no sepsis-related anemia has yet been reported. Moreover,

anemia is a good indicator for distinguishing KD from sepsis and other infectious diseases. Previous studies have reported that elevated alanine aminotransferase (ALT) is an important

laboratory finding for KD, as well as that abnormal liver function including ALT accounts for 37% of total KD children. The elevation of ALT in most children was only slightly elevated, less

than twice that of the normal threshold17,18,19. Elevated ALT is also one of the biochemical indicators for predicting IVIG resistance in KD and assisting in incomplete KD diagnosis2,20. In

our study, the ALT in KD children was significantly higher than that in the sepsis patients and was found to be the most important laboratory indicator (with the highest score of 100) in

this novel nomogram model. Several studies have shown that WBC, CRP, and PCT increased in KD children21, and it has been reported that a high CRP level is one of the important laboratory

indicators for predicting IVIG resistance in KD22. However, CRP, PCT, and other inflammatory indicators are also significantly increased in sepsis patients and have been proposed as

potential markers for diagnosing neonatal sepsis23. Studies have shown that PCT is significantly higher in KD children than in viral infections and other autoimmune diseases24. In our study,

the levels of WBC, CRP, and PCT in KD patients were increased but lower than the levels of sepsis patients, indicating that the immune-pathogenesis of KD lies somewhere between sepsis and

viral infection. Antibiotics are vital for treating sepsis but may not be as important in the treatment of KD. According to the literature review, this report is the first to identify KD and

sepsis by using ordinary laboratory indicators. Based on clinical laboratory results, we constructed a novel nomogram model with five laboratory markers (WBC, anemia, CRP, PCT, and ALT) for

predicting KD and sepsis, which will help clinicians treat KD and sepsis patients more precisely. Furthermore, the timely recognition and treatment of KD can reduce coronary artery damage

or progression to KDSS. However, the results of this study still need to be clarified through more cases and from more areas. Kuo et al.25 reported that among the total of 1,065 KD patients,

26 cases admitted to the ICU were identified during a 10-year study period. Shock (73.1%, n = 19) was the most common reason for KD patients to be admitted to the ICU, and ICU KD patients

were more likely to receive antibiotics (but not for every KD patient), albumin infusion, and steroids, as well as to require a second dose of IVIG therapy. Kanegaye et al.26 reported that

patients with KDSS may be resistant to immunoglobulin therapy and require additional anti-inflammatory treatment. In this article, antibiotics were not among the treatment suggestion for

KDSS. Altogether, if patients presented with fever and hemodynamic failure with two or three signs suggesting KD, both IVIG and antibiotics were administered in case of KD with uncertain

infections, or only IVIG when infections were excluded. CONCLUSION This is the first study to use a nomogram to develop a novel prediction model that shows that WBC, anemia, PCT, CRP,

albumin, and ALT may help clinicians differentiate KD from sepsis with high accuracy. MATERIALS AND METHODS A retrospective analysis was conducted on the medical records of patients who were

admitted to the maternal and child health hospital of the Baoan District in Shenzhen, China from 2017 to 2019. All the children were younger than 18 years of age. KD diagnoses were made

according to the American Heart Association (AHA) criteria and showed at least four of the following five clinical manifestations: bulbous conjunctival congestion, lips or oral cavity

changes, hand and foot symptoms, skin manifestations, and cervical lymph node enlargement2,27. Incomplete or atypical KD (N = 47) diagnosis was made in patients with a history of fever

lasting more than 5 days but fewer than four of the five major KD clinical diagnostic criteria, with echocardiography showing evidence of coronary artery changes28. We compared KD (including

typical KD, atypical KD, and Kawasaki disease shock syndrome (KDSS)) with sepsis but not septic shock. Our hospital only had a few cases of KDSS (fewer than 10 cases) during the study

period of our recent publication29. Sepsis is defined according to the “2016 Surviving Sepsis Campaign”30. The laboratory data of the patients enrolled in this study, including complete

blood count/differential count (CBC/DC), C-reactive protein (CRP), aspartate aminotransferase (AST), alanine transaminase (ALT), albumin, procalcitonin (PCT), sodium, and erythrocyte

sedimentation rate (ESR), were all collected prior to IVIG treatment in KD patients and before antibiotics were administered to the sepsis patients during admission. The anemia criteria were

defined by age according to the World Health Organization (WHO)31. STATISTICS The data in this study were analyzed with mean ± standard deviation (x ± s) used for measurement data and n and

percentage used for enumeration data. We compared the normal distribution data using independent sample t-test or single factor analysis of variance. We adopted rank sum test to compare

non-normal distribution data. The Chi-square test was used for counter measurement. A p-value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Multivariate logistic regression was

applied to analyze the influencing factors of KD and sepsis. Some continuous data were converted into classified data (WBC, neutrophil percentage, CRP, albumin, and ESR), according to the

cutoff value when the area of the ROC curve is the maximum value. In part, according to the reference range of the normal values, the upper-limit levels as the cutoff point were converted

into classified data (platelet, PCT, ALT, AST). We developed the nomogram model using the result of the multivariate logistics regression model to show the odds ratio and β-factor of each

predictor. We adopted Hosmer and Lemeshow to test whether the logistic prediction equation was suitable. The performance of the nomogram was evaluated as reported by Harrell et al.32.

Furthermore, the validation group was used to verify the scoring results of the nomogram, draw the ROC curve, and calculate the area under the curve. The highest point of the Youden index

was used to calculate the sensitivity and specificity of the verification group. The calibration of the models can be assessed using calibration plots, which can predict probabilities

against the actual observed risk10. SPSS 13.0 statistical software was used for the analysis, and the nomogram was drawn based on the R software (Math Soft, Cambridge, Massachusetts). ETHICS

APPROVAL AND CONSENT TO PARTICIPATE This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. The Institutional Review Board of Baoan Maternal and Child Health Hospital,

Shenzhen, China approved the study (IRB No. LLSCHY2019-07-01-02). PATIENT CONSENT This retrospective data analysis was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Baoan Maternal and Child

Health Hospital (IRB No. LLSCHY2019-07-01-02). The need of informed consent in this study was waived. DATA AVAILABILITY The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are

available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. REFERENCES * Han, J. W. Factors predicting resistance to intravenous immunoglobulin and coronary complications in Kawasaki

disease: IVIG resistance in Kawasaki disease. _Korean Circ. J._48(1), 86–88 (2018). Article PubMed Google Scholar * McCrindle, B. W. _et al._ Diagnosis, treatment, and long-term

management of Kawasaki disease: A scientific statement for health professionals from the American Heart Association. _Circulation_135(17), e927–e999 (2017). Article PubMed Google Scholar

* Dayasiri, K. _et al._ Incomplete Kawasaki disease with coronary aneurysms in a young infant of 45 days presented as neonatal sepsis. _Ceylon Med. J._63(1), 26–28 (2018). Article CAS

PubMed Google Scholar * Lin, Y. J. _et al._ Early differentiation of Kawasaki disease shock syndrome and toxic shock syndrome in a pediatric intensive care unit. _Pediatr. Infect. Dis.

J._34(11), 1163–1167 (2015). Article PubMed Google Scholar * Song, D. _et al._ Risk factors for Kawasaki disease-associated coronary abnormalities differ depending on age. _Eur. J.

Pediatr._168(11), 1315–1321 (2009). Article PubMed Google Scholar * Singh, S., Sharma, A. & Jiao, F. Kawasaki disease: Issues in diagnosis and treatment—A developing country

perspective. _Indian J. Pediatr._83(2), 140–145 (2016). Article PubMed Google Scholar * O’Brien, J. M. Jr. _et al._ Insurance type and sepsis-associated hospitalizations and

sepsis-associated mortality among US adults: A retrospective cohort study. _Crit. Care_15(3), R130 (2011). Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Batzofin, B. M., Sprung, C. L.

& Weiss, Y. G. The use of steroids in the treatment of severe sepsis and septic shock. _Best Pract. Res. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab._25(5), 735–743 (2011). Article CAS PubMed Google

Scholar * Nguyen, H. B. _et al._ Implementation of a bundle of quality indicators for the early management of severe sepsis and septic shock is associated with decreased mortality*. _Crit.

Care Med._35(4), 1105–1112 (2007). Article PubMed Google Scholar * Alba, A. C. _et al._ Discrimination and calibration of clinical prediction models: Users’ guides to the medical

literature. _JAMA_318(14), 1377–1384 (2017). Article PubMed Google Scholar * Dominguez, S. R. _et al._ Kawasaki disease in a pediatric intensive care unit: A case-control study.

_Pediatrics_122(4), e786–e790 (2008). Article PubMed Google Scholar * Ballmer, P. E. Causes and mechanisms of hypoalbuminaemia. _Clin. Nutr._20(3), 271–273 (2001). Article CAS PubMed

Google Scholar * Kuo, H. C. _et al._ Serum albumin level predicts initial intravenous immunoglobulin treatment failure in Kawasaki disease. _Acta Paediatr._99(10), 1578–1583 (2010). Article

PubMed Google Scholar * Huang, Y. H. & Kuo, H. C. Anemia in Kawasaki disease: Hepcidin as a potential biomarker. _Int. J. Mol. Sci._ https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mgene.2018.05.079

(2017). Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Ling, X. B. _et al._ A diagnostic algorithm combining clinical and molecular data distinguishes Kawasaki disease from other febrile

illnesses. _BMC Med._9, 130 (2011). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Kuo, H. C. _et al._ Inflammation-induced hepcidin is associated with the development of anemia

and coronary artery lesions in Kawasaki disease. _J. Clin. Immunol._32(4), 746–752 (2012). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Eladawy, M. _et al._ Abnormal liver panel in acute Kawasaki

disease. _Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J._30(2), 141–144 (2011). Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Uehara, R. _et al._ Serum alanine aminotransferase concentrations in patients

with Kawasaki disease. _Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J._22(9), 839–842 (2003). Article PubMed Google Scholar * Zulian, F. _et al._ Acute surgical abdomen as presenting manifestation of Kawasaki

disease. _J. Pediatr._142(6), 731–735 (2003). Article PubMed Google Scholar * Egami, K. _et al._ Prediction of resistance to intravenous immunoglobulin treatment in patients with Kawasaki

disease. _J. Pediatr._149(2), 237–240 (2006). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Petrarca, L. _et al._ Difficult diagnosis of atypical Kawasaki disease in an infant younger than six

months: A case report. _Ital. J. Pediatr._43(1), 30 (2017). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Tremoulet, A. H. _et al._ Resistance to intravenous immunoglobulin in

children with Kawasaki disease. _J. Pediatr._153(1), 117–121 (2008). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Jia, Y., Wang, Y. & Yu, X. Relationship between blood lactic

acid, blood procalcitonin, C-reactive protein and neonatal sepsis and corresponding prognostic significance in sick children. _Exp. Ther. Med._14(3), 2189–2193 (2017). Article CAS PubMed

PubMed Central Google Scholar * Cho, H. J. _et al._ Procalcitonin levels in patients with complete and incomplete Kawasaki disease. _Dis. Mark._35(5), 505–511 (2013). Article Google

Scholar * Kuo, C. C. _et al._ Characteristics of children with Kawasaki disease requiring intensive care: 10 years’ experience at a tertiary pediatric hospital. _J. Microbiol. Immunol.

Infect._51(2), 184–190 (2018). Article PubMed Google Scholar * Kanegaye, J. T. _et al._ Recognition of a Kawasaki disease shock syndrome. _Pediatrics_123(5), e783–e789 (2009). Article

PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Burns, J. C. Kawasaki syndrome. _Lancet_364, 533–544 (2004). Article PubMed Google Scholar * Rossomando, V. & Baracchini, A. Atypical and

incomplete Kawasaki disease. _Ital. J. Pediatr._49(9), 419 (1997). CAS Google Scholar * Jin, P. _et al._ Kawasaki disease complicated with macrophage activation syndrome: Case reports and

literature review. _Front. Pediatr._7, 423 (2019). Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Rhodes, A. _et al._ Surviving sepsis campaign: International guidelines for management

of sepsis and septic shock: 2016. _Intens. Care Med._43(3), 304–377 (2017). Article Google Scholar * Goodhand, J. R. _et al._ Prevalence and management of anemia in children, adolescents,

and adults with inflammatory bowel disease. _Inflamm. Bowel Dis._18(3), 513–519 (2012). Article PubMed Google Scholar * Harrell, F. E. Jr. _et al._ Evaluating the yield of medical tests.

_JAMA_247(18), 2543–2546 (1982). Article PubMed Google Scholar Download references ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS We are particularly thankful to the patients who participated in this study. This study

was supported by the Sanming Project of Medicine in Shenzhen (SZSM201606088) and Shenzhen Basic Research Grants (JCYJ 20170413165432016). AUTHOR INFORMATION Author notes * These authors

contributed equally: Xiao-Ping Liu, Yi-Shuang Huang and Ho-Chang Kuo. AUTHORS AND AFFILIATIONS * The Department of Emergency and Pediatrics, Shenzhen Baoan Women’s and Children’s Hospital,

Jinan University, #56, Yulv St., Baoan District, Shenzhen, 518102, Guangdong, China Xiao-Ping Liu, Yi-Shuang Huang, Han-Bing Xia, Yi-Sun, Wei-Dong Huang, Xin-Ling Lang, Chun-Yi Liu & Xi

Liu * Kawasaki Disease Center and Department of Pediatrics, Kaohsiung Chang Gung Memorial Hospital and College of Medicine, Chang Gung University, #123, Dapei Rd., Niaosong, Kaohsiung,

83301, Taiwan Ho-Chang Kuo Authors * Xiao-Ping Liu View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Yi-Shuang Huang View author publications You can

also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Ho-Chang Kuo View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Han-Bing Xia View author

publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Yi-Sun View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Wei-Dong Huang View

author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Xin-Ling Lang View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Chun-Yi

Liu View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Xi Liu View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar

CONTRIBUTIONS X.P.L. and Y.S.H. conceptualized and designed the study and conceptualized the analyses for this article. H.C.K. revised each version of the manuscript. H.B.X. conceptualized

and designed the study, participated in the design of the questionnaire, conceptualized the analyses for this article, supervised all data analyses, and reviewed and revised each version of

the manuscript. Y.S. participated in the design of the questionnaire, conducted the analyses, and created the tables. X.L.L., W.D.H., C.Y.L. and X.L. helped conceptualize this article,

contributed to the interpretation of the study findings, and reviewed and revised the manuscript. All authors participated in team discussions of data analyses, approved the final manuscript

as submitted, and have agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work. CORRESPONDING AUTHORS Correspondence to Chun-Yi Liu or Xi Liu. ETHICS DECLARATIONS COMPETING INTERESTS The

authors declare no competing interests. ADDITIONAL INFORMATION PUBLISHER'S NOTE Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional

affiliations. RIGHTS AND PERMISSIONS OPEN ACCESS This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution

and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if

changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the

material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will

need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. Reprints and permissions ABOUT THIS ARTICLE

CITE THIS ARTICLE Liu, XP., Huang, YS., Kuo, HC. _et al._ A novel nomogram model for differentiating Kawasaki disease from sepsis. _Sci Rep_ 10, 13745 (2020).

https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-70717-4 Download citation * Received: 07 September 2019 * Accepted: 16 March 2020 * Published: 13 August 2020 * DOI:

https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-70717-4 SHARE THIS ARTICLE Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content: Get shareable link Sorry, a shareable link is not

currently available for this article. Copy to clipboard Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative