Whole genome analysis of extensively drug resistant mycobacterium tuberculosis strains in peru

- Select a language for the TTS:

- UK English Female

- UK English Male

- US English Female

- US English Male

- Australian Female

- Australian Male

- Language selected: (auto detect) - EN

Play all audios:

ABSTRACT Peru has the highest burden of multidrug-resistant tuberculosis in the Americas region. Since 1999, the annual number of extensively drug-resistant tuberculosis (XDR-TB) Peruvian

cases has been increasing, becoming a public health challenge. The objective of this study was to perform genomic characterization of _Mycobacterium tuberculosis_ strains obtained from

Peruvian patients with XDR-TB diagnosed from 2011 to 2015 in Peru. Whole genome sequencing (WGS) was performed on 68 XDR-TB strains from different regions of Peru. 58 (85.3%) strains came

from the most populated districts of Lima and Callao. Concerning the lineages, 62 (91.2%) strains belonged to the Euro-American Lineage, while the remaining 6 (8.8%) strains belonged to the

East-Asian Lineage. Most strains (90%) had high-confidence resistance mutations according to pre-established WHO-confident grading system. Discordant results between microbiological and

molecular methodologies were caused by mutations outside the hotspot regions analysed by commercial molecular assays (_rpoB_ I491F and _inhA_ S94A). Cluster analysis using a cut-off ≤ 10

SNPs revealed that only 23 (34%) strains evidenced recent transmission links. This study highlights the relevance and utility of WGS as a high-resolution approach to predict drug resistance,

analyse transmission of strains between groups, and determine evolutionary patterns of circulating XDR-TB strains in the country. SIMILAR CONTENT BEING VIEWED BY OTHERS WHOLE GENOME

SEQUENCING OF MULTIDRUG-RESISTANT _MYCOBACTERIUM TUBERCULOSIS_ ISOLATES COLLECTED IN THE CZECH REPUBLIC, 2005–2020 Article Open access 03 May 2022 WHOLE GENOME SEQUENCING OF CLINICAL SAMPLES

REVEALS EXTENSIVELY DRUG RESISTANT TUBERCULOSIS (XDR TB) STRAINS FROM THE BEIJING LINEAGE IN NIGERIA, WEST AFRICA Article Open access 30 August 2021 WHOLE-GENOME SEQUENCING-BASED ANALYSES

OF DRUG-RESISTANT _MYCOBACTERIUM TUBERCULOSIS_ FROM TAIWAN Article Open access 13 February 2023 INTRODUCTION Tuberculosis (TB) is a preventable and curable disease and one of the top 10

causes of death in the world1. Resistance to drugs used in the treatment of TB is a major threat to the strategies that are being deployed to control and eliminate the multidrug-resistant TB

(MDR-TB) and extensively drug-resistant TB (XDR-TB)2,3,4. Both forms of this pathology are becoming more prevalent through the years and require an expensive and prolonged treatment that

produces greater morbidity, toxicity and mortality2,5. In 2019, it was reported that 3.3% of new TB cases and 18% of previously treated cases globally were diagnosed with MDR-TB, of which an

estimated proportion of 6% (12,350 reported cases) were XDR-TB1. Moreover, XDR-TB has the lowest treatment success rate (39%) compared to other forms of TB2. In the region of the Americas,

XDR-TB is present being Peru the country with the highest burden1. The first Peruvian case of XDR-TB was detected in 19996, and throughout the years the number of cases has progressively

increased, adding up to 944 cases until 20177,8. The national distribution of XDR-TB corresponds to the epidemiological situation of TB in the country. Approximately, 85–88% of XDR-TB cases

are concentrated in the capital city of Lima and Callao, with the eastern part of Lima being particularly one of the areas with the highest number of cases of this form of TB7,9. Drug

resistance of mycobacterial strains is detected through genotypic or phenotypic laboratory tests that detect the presence of DNA mutations conferring resistance or the growth of

_Mycobacterium tuberculosis_ (MTB) in the presence of anti-TB drugs, respectively. However, these methodologies are restricted to the analysis of a limited number of resistance genes or to

the slow mycobacterial duplication time, respectively. All of this makes it difficult to obtain complete and rapid results. To determine genetic relationships, analysis of the restriction

fragment length polymorphisms of the _IS6110_ gene (IS6110-RFLP), spacer oligonucleotide typing (Spoligotyping) and mycobacterial interspersed repetitive units-variable number of DNA tandem

repeats (MIRU-VNTR) have been used globally. These methodologies have also been applied in Peru for exploration of the genetic diversity of drug resistant TB strains10,11,12. However, the

problem using these conventional techniques for genotyping is that they explore polymorphic genetic regions that cover less than 1% of the mycobacterial genome, significantly limiting their

power of differentiation between strains that are very close at the genetic level13,14. Recently, the revolution of Next Generation Sequencing (NGS) technology and its wider availability

have allowed to perform Whole Genome Sequencing (WGS) analysis to provide information about speciation, drug resistance prediction and better determination of relatedness for epidemiologic

purposes15,16,17. In this way it is possible to obtain a greater amount of information that allows a complete characterization and discrimination of strains with repeated or ambiguous

conventional genotypic patterns18,19. However, to date no high-resolution genomic study has been performed on Peruvian XDR-TB strains. The objective of this study is to characterize the

genomic variability of the XDR-TB strains circulating in Peru, using the NGS-based WGS analysis. We performed an approximation of their molecular epidemiology and determined the evolutionary

relationships of the XDR-TB Peruvians strains. METHODS SAMPLE COLLECTION MTB strains from hospitals and public health laboratories throughout Peru are sent daily to the National Reference

Laboratory for Mycobacteria (NRLM), of the Peruvian National Institute of Health (NIH), for TB confirmation and evaluation of antimicrobial susceptibility. A total of 68 XDR-TB strains,

according to phenotypic results, stored at NRLM were included in this study. All recovered strains correspond to patients with active pulmonary TB diagnosed between 2011 and 2015. These

strains were randomly selected from the entire country. ETHICAL STATEMENT Approval for the use and processing of preserved strains was obtained from the Institutional Committee for Research

Ethics of the Peruvian NIH (reference number OT-0021-17). Identity of the patients was blinded to the researchers using a dual coding system from this study. GENOTYPIC AND PHENOTYPIC

CONFIRMATION Cryopreserved MTB strains were inoculated in Middlebrook 7H9 media (Becton Dickinson, Sparks, USA) for seven days. Subsequently, 0.2 mL of 7H9 supernatant was transferred to

Lowenstein–Jensen (LJ) medium and incubated for a minimum of three weeks to obtain a moderate development. Genotypic confirmations of resistance against rifampicin and isoniazid were

performed using the line probe assay GenoType MTBDR_plus_ v2 (Hain Lifescience, Nehren, Germany), according to the manufacturer's protocol. Phenotypic confirmation was performed using

the proportion method (PM) in Middlebrook 7H10 media (Becton Dickinson, Sparks, USA) to assess the resistance to isoniazid (0.2 μg/mL, 1.0 μg/mL), rifampicin (1.0 μg/mL), levofloxacin (1.0

μg/mL), capreomycin (10.0 μg/mL) and kanamycin (5.0 μg/mL). All the work related to the manipulation of live bacteria was carried out in facilities with biosafety level 3 of the NRLM. DNA

EXTRACTION AND WHOLE GENOME SEQUENCING Genomic DNA extractions were performed using the GeneJET Genomic DNA Purification kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, USA) according to

manufacturer's recommendations. Double-stranded DNA concentration was quantified using the Qubit dsDNA HS Assay kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, USA). Sequencing libraries were

prepared using 1 ng of each DNA sample with Nextera XT Library Preparation kit. Whole genome sequencing was carried out at NIH (Lima, Peru) using Illumina MiSeq platform (Illumina, San

Diego, USA) to generate paired-end sequencing reads. BIOINFORMATIC ANALYSIS All computational analyses were performed by the bioinformatics department of the NRLM and were entirely set on

the ubuntu distribution of Linux. PURITY ASSESSMENT AND QUALITY FILTERING Quality evaluation of paired-end reads was performed using FastQC v0.11.9

(https://www.bioinformatics.babraham.ac.uk/projects/fastqc). The presence of specific reads for _M. tuberculosis_ complex species was verified with Kraken2 v2.0.7 (MiniKraken2 v2

database)20. Verified paired-end reads were filtered with Trimmomatic v0.3821 using default values and a minimum Phred score of 20. Only filtered paired-end reads (95.6% of total raw reads)

were used for downstream analysis. ASSEMBLY, ALIGNMENT, AND VARIANT CALLING Filtered paired-end reads were mapped against the H37Rv reference genome (GenBank accession number: NC_000962.3)

using BWA v0.7.1722. Identification of duplicate reads and sorting were done with Picard-tools v2.18.25 (http://broadinstitute.github.io/picard). Mapping depth and coverage was determined

using samtools v1.923, bedtools v2.29.024 and a custom script in R v3.6.125. For variant call a local realignment of mapped reads was performed using HaplotypeCaller algorithm, implemented

in GATK v3.826. A hard-filtering approach was performed with VCFtools v0.1.1627 to select variants with the following criteria: mapping quality ≥ 60, variant depth ≥ 10X and frequency of

reads supporting alternate allele ≥ 0.75. Genome positions with missing genotypes (due no coverage of reads or less than 10X depth coverage) in a minimum of 10% of all strains, and variants

identified in repetitive regions (PE, PPE and PE-PGRS families) were excluded. Selected variants were annotated using SnpEff v4.3 T28. Concatenated genome-wide Single Nucleotide

Polymorphisms (SNPs) sequences were generated for subsequent analysis. RESISTANCE GENETIC VARIANTS Resistance-associated genes were analysed to evaluate phenotypic resistance to rifampicin

(_rpoB_, _rpoC_, _rpoA_), isoniazid (_katG_, _inhA_, _mabA_, _kasA_, _furA_, _ndh_, _mshA_, _nat_ and _oxyR-ahpC_ region), levofloxacin (_gyrA, gyrB_) and second-line injectable drugs (_rrs,

eis, tlyA_). Variant allelic frequency of at least 0.10 was set for these genes. Resistance genetic variants were visually confirmed using the Artemis v18.129. Variants were compared with

those reported in the TB Drug Resistance Mutation Database (https://tbdreamdb.ki.se) and confidence was graded based on the technical guide to resistance-associated mutations reported by the

World Health Organization (WHO)30. LINEAGE/SUBLINEAGE AND FAMILY DETERMINATION MTB lineages and sublineages determination was performed with Kvarq v0.12.231 using the set of SNPs proposed

by Coll _et al_.32. MTB families were determined using the in silico detection of 43 unique spacers in the direct repeat locus using SpoTyping v2.033. Then, the presence or absence of this

spacers were analysed in the SITVIT2 database (http://www.pasteur-guadeloupe.fr:8081/SITVIT2) for the determination of the corresponding ‘Spoligo-International-Type’ (SIT). EVOLUTIONARY

ANALYSIS A maximum likelihood phylogenomic tree was built from concatenated genome-wide SNPs using RAxML-NG v0.9.034. A 25 random and 25 parsimony-based starting trees and 1000 standard

non-parametric bootstrap replicates were used to assess branch support. A general time-reversible substitution model was selected based on Akaike’s information criterion using jModelTest235.

The tree was rooted using a ‘Lineage seven’ strain (SRA ID: ERR181435). An alternative phylogenomic tree was built using additional non-Peruvians 221 XDR-TB strains for an international

comparison (Supplementary Table S1). TRANSMISSION CLUSTERS DETERMINATION Genomic transmission clusters were determined using genome-wide SNPs independently of the epidemiological data. A

cut-off value of no more than 10 SNPs distance, pre-established for a high prevalence area36,37,38,39, was used to group the strains into the same recent transmission genetic cluster. SNP

distances were obtained from nucleotide pairwise comparisons of all sequenced strains using the R package Ape v5.440. Transmission network was constructed using the SeqTrack41 algorithm from

R package Adegenet v2.1.342. RESULTS PATIENT CHARACTERISTICS 68 XDR-TB strains were included. Five (7.4%) strains were obtained from patients diagnosed in 2011, two (2.9%) in 2012, 18

(26.5%) in 2013, 23 (33.8%) in 2014 and 20 (29.4%) in 2015. Likewise, 38 (55.9%) strains were initially obtained from men and the rest from women. Their age ranged from 15 to 78 years with a

mean of 36 years (interquartile range 25.3–44.5). 51 (75.0%) cases had received a previous anti-TB treatment (Table 1). 58 (85%) strains belonged to patients from Lima region and Callao

province (51 from Lima and 7 from Callao). Regarding the strains of the Lima region, 30 (59%) came from districts of the east zone_,_ 16 (31%) from the centre and north, 3 (6%) from the

south, and 2 (4%) from other provinces (Supplementary Fig. S1). In addition, Piura, La Libertad, Loreto, Ancash, Ucayali, Arequipa and Madre de Dios regions had one strain each, while the

Ica region had three strains (Supplementary Table S2). SEQUENCING AND GENOME ASSEMBLY An average of 935,183 raw sequencing reads per fastq file were obtained. Two fastq files (_forward_ and

_reverse_) were generated for every sample. The minimum, maximum and average genome depth of sequencing obtained were 53X, 153X and 88X, respectively. All strains had reads covering more

than 99% of the H37Rv genome (Supplementary Table S2). ANTIMICROBIAL RESISTANCE All strains showed simultaneous phenotypic resistance to rifampicin, isoniazid, and levofloxacin. However,

they showed differences in resistance to second-line injectable drugs (Table 1). Discordant results between phenotypic and genotypic methods were found for isoniazid (strain XDR-28) and

rifampicin (strain XDR-19) showing resistance results only through the phenotypic method (Supplementary Table S2) and were analysed in another study43. Concerning rifampicin resistance, all

strains had resistance mutations located at _rpoB_ gene. From these, 67 (98.5%) were considered high-confident mutations located inside the rifampicin-resistance-determining region (RRDR) of

the _rpoB_ gene, while only one strain (1.5%) presented a mutation outside this region (I491F). The most frequent mutations were S450L and D435V. Only one strain had the double mutation

H445N + S431R. The isoniazid resistant strains showed mutations in _katG_ and _inhA_ genes. Only one mutation in _katG_ (S315T), three mutations in the promoter region (g-17t, c-15t and

t-8c) and one mutation in the coding region (S94A) of _inhA_ were found. There were four strains with double mutation, S315T + c-15t, and one with S315T + t-8c (Table 2). Levofloxacin

resistance was predominately caused by mutations occurring in the quinolone-resistance-determining region (QRDR) of _gyrA_ gene and contained nine different mutations, whereas _gyrB_ showed

only three. In the _gyrA_ gene, the codon 94 showed the greatest variability (five different mutations). Only two strains presented mutations in both genes. Finally, one strain (1.5%) did

not present mutations in either of the two genes. Resistance to kanamycin and capreomycin was driven by mutations occurring at _rrs_ (a1401g, c1402t and g1484t), _tlyA_ (all frame shifts)

and _eis_ (c-14t) genes. However, no mutations were detected in two strains for the screened genes. Strains with exclusive resistance to kanamycin only presented the _rrs_ a1401g mutation,

whereas two strains had no mutations in any of the three genes analysed. Exclusive resistance to capreomycin was caused by several frameshifts’ mutations occurring in _tlyA_ gene. However,

there were three strains with no detected mutations in any of the analysed genes. In general, 96, 85 and 90% (average 90%) of strains had high-confident mutations for resistance to

rifampicin, isoniazid and both second-line drugs, respectively (Table 2). Several synonymous and nonsynonymous mutations located in additional resistant-associated genes were evidenced to be

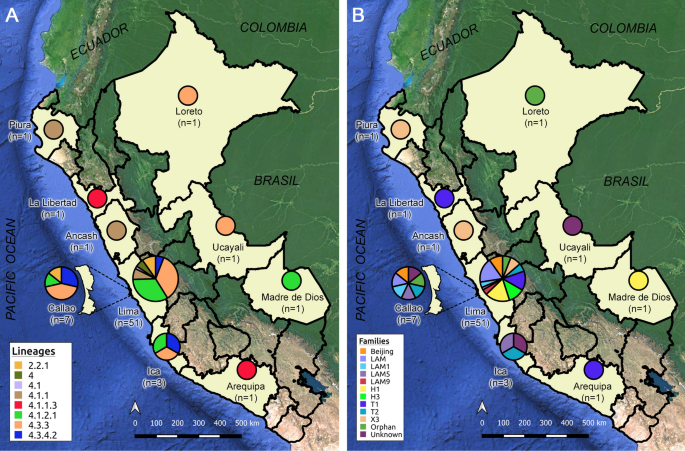

present together with the mutations described above (Supplementary Table S3). LINEAGES AND EVOLUTIONARY RELATIONSHIPS Lineage’s analysis determined that 62 (91%) XDR-TB strains belong to

the Euro-American Lineage (Lineage 4) and 6 (9%) to the East-Asian Lineage (Lineage 2). 59 strains from Lineage 4 were able to be classified into six sublineages, while three could only be

assigned as belonging to lineage 4. All strains from Lineage 2 were represented by sublineage 2.2.1. Five strains of Lineage 2 circulated in the Lima region, while the remaining strain

circulated in the province of Callao (Fig. 1). The presence of 18 strains belonging to the LAM family was found (LAM/SIT1355 [n = 10; 14.7%], LAM1/SIT469 [n = 3; 4.4%], LAM5/SIT93 [n = 2;

2.9%], LAM5/SIT1160 [n = 1; 1.5%], LAM9/SIT42 [n = 2; 2.9%]), 16 strains belonging to the Haarlem family (H1/SIT47 [n = 9; 13.2%], H1/SIT62 [n = 1; 1.5%], H3/SIT3001 [n = 6; 8.8%]), 14

strains belonging to the T family (T1/SIT53 [n = 6; 8.8%], T1/SIT219 [n = 2; 2.9%], T1/SIT535 [n = 1; 1.5%], T2/SIT52 [n = 5; 7.4%]), 6 strains belonging to the X family (X3/SIT91 [n = 5;

7.4%], X3/SIT3780 [n = 1; 1.5%]), and 6 (8.8%) strains belonging to the Beijing/SIT1 family. Likewise, the presence of a reduced number of strains with orphan (n = 4; 4%) and unknown (n = 4;

4%) spoligotypes was also observed (Supplementary Fig. S2 and Table S2). The northern strains of the country belonged to Piura (4.1.1/X3/SIT91; n = 1), La Libertad (4.1.1.3/T1/SIT219; n =

1) and Loreto (4.3.3/Orphan; n = 1). In the centre of the country, the regions of Lima, Ica and the province of Callao showed to contain the greatest genetic diversity with respect to the

entire country, with six, three and four sublineages respectively. The rest of the central regions were integrated by Ancash (4.1.1/X3/SIT91; n = 1) and Ucayali (4.3.3/Unknown/222; n = 1).

Finally, in the South of the country, strains were found to belong to Arequipa (4.1.1.3/T1/SIT219; n = 1) and Madre de Dios (4.1.2.1/H1/SIT62; n = 1) (Fig. 1 and Supplementary Table S2). The

maximum likelihood phylogenomic tree confirmed the lineage and sublineage classification and showed additional subclassification for strains belonging to the same sublineage. Interestingly,

no correlation between phylogenomic clades and specific mutations conferring resistance was observed. Spoligotypes with ‘Orphans’ and ‘Unknown’ SITs could be characterized by evolutionary

and lineage analysis. Three strains with ‘Unknown’ SITs got aligned within the sublineage 4.3.3 group, showing an evolutionary similarity with members of the H3 family, while the strains

with ‘Orphans’ SITs were in the groups belonging to sublineages 4.3.3 (n = 3) and 4.1.2.1 (n = 1) (Supplementary Fig. S3). A close evolutionary relationship was found between strains from

Arequipa (XDR-10) and La Libertad (XDR-05), being the only representatives of the sublineage 4.1.1.3 in the entire country and exhibiting an important degree of genomic differentiation with

the other strains (Fig. 2). Global evolutionary relatedness showed that Peruvian XDR-TB strains were grouped in different monophyletic clades and had a close relatedness with XDR-TB strains

of Lineages 4 and 2 of European countries (Supplementary Fig. S4). TRANSMISSION CLUSTER DETERMINATION The analysis of pairwise genetic differences showed a high number of strains that

differed by large amounts of SNPs. The genetic distance between strains varied from 5 to 1,272 SNPs with an interquartile range of 373 and a median of 772 (Supplementary Fig. S5). The WGS

analysis determined that most strains were not related at genetic level with only 23 strains forming part of nine transmission clusters (clustering rate of 34%), each one comprising between

two and five strains (Fig. 3 and Supplementary Fig. S6). These clusters consisted mainly of strains from Lineage 4 (91.3%). The largest clusters were integrated by strains of the sublineages

4.3.3 (cluster 5; n = 5) and 4.1.2.1 (cluster 4; n = 4). Clusters 1 (sublineage 4.1.1/X3/SIT91) and 8 (sublineage 4.3.4.2/LAM1/SIT469) were integrated by strains with sublineages not

present in the other clusters and presented an average distance to the closest cluster of 525 SNPs. The rest of the clusters of Lineage 4 were integrated by strains of sublineages 4.1.2.1

and 4.3.3. Thus, clusters 2 and 4 (sublineage 4.1.2.1/H1/SIT47), and 3 (sublineage 4.1.2.1/T2/SIT52) presented an average distance between them of 123.5 SNPs. While clusters 5, 6 and 7

(sublineage 4.3.3/LAM/SIT1355) presented an average distance between them of 17.5 SNPs. The cluster belonging to Lineage 2 (sublineage 2.2.1/Beijing/SIT1) had a considerable minimum distance

of 1198 SNPs with the nearest cluster of Lineage 4 (Fig. 3). All clustered strains came from Lima region (n = 21) and Callao province (n = 2). Regarding the strains of Lima region, 17

belonged to the east zone, one to the centre (in the area bordering the east zone), two to the south zone and one to the provinces (Supplementary Table S4). Regarding the variability of

sources of infection, clusters 2 and 6 were composed of strains belonging to a single infection district (Ate and El Agustino, respectively), while the rest of clusters were integrated by at

least two districts. The cluster with more members (cluster 5) was integrated by strains from the bordering districts of San Juan de Lurigancho and El Agustino. In the same way, cluster 4

was formed by four strains from the geographically close districts of San Juan de Lurigancho, Santa Anita and La Victoria. The remaining groups consisted of only two strains that came mainly

from geographically separate districts (Fig. 3). Regarding drug resistance, all the strains that made up the same cluster shared the mutations associated with resistance for rifampicin and

isoniazid drugs. The strains integrating clusters 1, 2, 3, and 9 (n = 8) shared the _rpoB_ S450L and _katG_ S315T mutations, likewise the strains integrating clusters 5, 6, 7 and 8 (n = 11)

shared the _rpoB_ D435V and _katG_ S315T mutations. Finally, the strains in cluster 4 shared the _rpoB_ H445R, _katG_ S315T and _inhA_ c-15t mutations. Regarding resistance to second-line

drugs, it was evidenced that not all the strains integrating a single cluster shared the same type of mutations. All the strains integrating clusters 1, 3 and 8 (n = 6) shared the _rrs_

a1401g and _gyrA_ D94G mutations. Similarly, all the strains in cluster 4 had the _tlyA_ V198_fs_ and _gyrA_ A90V mutations. However, clusters 7 and 9 (n = 4) presented variations in

resistance mutations only to levofloxacin, cluster 5 (n = 5) presented variations in resistance only to second-line injectables, and clusters 2 and 6 (n = 4) presented variations for both

types of drugs (Supplementary Table S4). DISCUSSION In our study, we found that most XDR-TB strains belonged to the Euro-American lineage (Linage 4), in agreement with studies that claim

that this lineage is the largest in the world and the more prevalent in America continent. In general, the geographical source of the sequenced samples was representative of XDR-TB affecting

the entire country: 85% of the included strains were from Lima and Callao, virtually the same proportion reported by Alarcon7 and Soto9. Another important finding is that there is a high

genomic diversity in our XDR-TB strains, based on the large number of sublineages obtained. However, recent transmission clusters were detected only in 34% of the strains analysed.

Concerning the mutations conferring resistance to antituberculosis drugs, currently in Peru, molecular resistance screening for first and second-line antituberculosis drugs is performed by

the line probe assays: GenoType MTBDR_plus_ v2 and GenoType MTBDR_sl_ v2. However, these assays only concentrate the analysis on genetic hotspots. Consistent with previous studies, our

results indicate that rifampicin resistance is mainly caused by mutations at codons 450, 445 and 435 of _rpoB_ gene44,45,46. We also detected Q432P mutation which has a high confidence grade

for rifampicin resistance development and S431R mutation which in turn has insufficient data according to WHO-NGS Technical Guide, despite having been associated with rifampicin resistant

phenotypes47. The rifampicin-discordant strain presented the I491F mutation located outside the RRDR. This mutation was previously reported in Peru43 and WHO consider it as a variant with

minimum confidence grade30. The isoniazid resistance was predominantly driven by the _katG_ S315T (AGC → ACC) mutation followed by _inhA_ c-15t. The rare variant _inhA_ g-17t was also

present in a low frequency in concordance to previous studies16,48. This mutation is indirectly detected by the GenoType MTBDR_plus_ v2. Finally, the isoniazid-discordant strain presented

the _inhA_ S94A mutation that is known to confer isoniazid resistance in clinical and experimental studies49, and was also previously identified in Peruvian strains43. Levofloxacin

resistance was mainly driven by mutations occurring at _gyrA_ gene. However, it also was detected the _gyrB_ E501D mutation which was previously associated with conferring resistance only to

Moxifloxacin or ciprofloxacin50,51, although our results indicate that it also confers resistance to levofloxacin and has never been reported before in Peruvian strains. Strains that did

not harbour mutations in either _gyrA_ or _gyrB_ genes suggests the existence of alternatives mechanisms of resistance like alterations in genes related to efflux pumps as well as DNA

mimicry52,53,54. The presence of strains showing mutations in both genes was evidenced. A double mutation has previously associated with higher minimum inhibitory concentrations and may be

associated with a decreased fitness55, but it could not be determined in this study. All only kanamycin resistant strains exhibited the _rrs_ a1401g mutation which is strongly associated

with resistance to high concentrations of kanamycin and amikacin30. Similarly, the simultaneous resistance to kanamycin and capreomycin is associated with high confidence mutations in the

_rrs_ gene (a1401g, c1402t and g1484t) associated with cross resistance to both drugs30. However, strains with no mutation at _rrs_, _eis_ or _tlyA_ genes suggest the presence of additional

resistance mechanism like alterations in L10 and L12 genes (for capreomycin resistance)56 and overexpression of _whiB7_ and efflux pump genes (for kanamycin resistance)57,58. This behaviour

has been previously reported in other studies, including Peru59,60. The analysis of phylogenetic SNPs and spoligotypes evidenced a predominance of Lineage 4 between the XDR-TB strains

analysed, which is in accordance with studies that claim that this lineage is the largest in the world and the more prevalent in America continent. The high circulation of XDR-TB strains

belonging to the sublineages 4.3.3/LAM, 4.3.3/LAM9, 4.3.4.2/LAM1, 4.3.4.2/LAM5 (n = 18) and 4.1.2.1/Haarlem (n = 10) are in accordance with the fact that they are considered the most widely

distributed sublineages worldwide. Likewise, the presence of the 4.1.1/X3 sublineage was evidenced, which has been observed mainly in America61. The high number of strains belonging to

Lineage 4 is a characteristic of America, and can be understood due to the colonization of the American continent by European emigrants (_founder effect_), which is estimated to have

occurred approximately between the years 1466 and 159362. The low frequency of Peruvian XDR-TB strains belonging to Lineage 2 reveals the recent incorporation of this Lineage into the

territory. The same behaviour has been reported in countries such as Ecuador and Chile63,64. The proportion of strains belonging to the Beijing family (8.8%) is very similar to what was

obtained in previous studies carried out in Peru in the years 2012 (9.3%)65 and in 2014 (9.2%)12. This permanence of the proportion of Lineage 2 strains through the years suggests that in

Peru the XDR-TB strains of the Beijing family would not necessarily be associated with greater virulent capacity or drug-resistant factors as previously determined66. Also, our study

suggests that until 2015, the XDR-TB strains belonging to Lineage 2 could still be geographically restricted to Lima region and Callao province. In general, most sublineages, in addition to

being present in some regions, were also present in Lima and Callao. This evidence the still existing centralization of the country's political-economic power in Lima and Callao.

However, additionally, the appearance of local sublineages was observed such as 4.1.1.3/T1/SIT219 which was present only in the regions of Arequipa and La Libertad, 2.2.1/Beijing/SIT1

present only in the Lima region and the Callao province, and 4.1.2.1/H1/SIT62 present only in Madre de Dios. These sublineages of local distribution would suggest the existence of restricted

transmission clusters present in these areas, which would include strains with different drug-resistant profiles. Coincidentally, the strains present in the geographically distant regions

of La Libertad (northern Peru) and Arequipa (southern Peru) revealed a transmission nexus not so distant between them (only 28 SNPs apart) evidencing the existence of a common genetic

ancestor for both regions. Our results establish that the LAM family was dominant among the Peruvian XDR-TB strains analysed, which is consistent with that evidenced in neighbouring South

American countries67,68,69,70,71,72. However, it disagrees with a previous study also carried out on Peruvian XDR-TB strains in which it was established that the dominant family was

Haarlem12. One possible reason for this disagreement is that the previous study included strains from previous years (2007–2009) which suggests the possible occurrence of a shift in the

prevalence of XDR-TB strain families in Peru over the years. On the other hand, a more recent study carried out on Peruvian MDR-TB strains agrees with our results, establishing the LAM

family as the predominant family in Peru73. The transmission clusters obtained confirm that XDR-TB strains are concentrated on the districts of Lima region which are more associated with

poverty, overcrowding and less access to health systems. These demographic variables have already been previously well characterized in studies of Peru and the world, but is not being

tackled appropriately74. The uniform composition of mutations associated with resistance to rifampicin and isoniazid drugs in the clusters establish that the transmission of strains in the

same cluster possibly occurred initially at the level of MDR-TB strains. However, a deep insight into the clusters revealed a heterogeneous composition within each cluster regarding

mutations associated with resistance to second-line drugs. This suggests the de novo emergence of the mutations that led to the XDR-TB phenotype. This discontinuity in the clusters of

mutations associated with second-line resistance and the low clustering rate (34%) of strains grouped in recent transmission chains suggest that the main mechanism of acquiring an XDR-TB

strain is not through by direct contact, but by failures in the individual treatment of less severe forms of tuberculosis. Furthermore, the large genetic distances observed indicate that

XDR-TB strains are related by common remote ancestors, rather than caused by recent transmission events. However, it should be noted that the lack of genomic characterization of all XDR-TB

strains circulating in the country, as well as strains isolated from relatives or direct contacts, may lead to the existence of missing links that underestimate the true proportion of recent

transmission events in Peruvian community. The fact that clusters 2, 3 and 4 shared the 4.1.2.1 sublineage (average distance of 123.5 SNPs) and that clusters 5, 6 and 7 shared the 4.3.3/LAM

sublineage (average distance of 17.5 SNPs) establishes that Whole genome sequencing showed a higher resolution capacity in Peruvian XDR-TB strains compared to the classic spoligotyping

system and the previously proposed barcode system32. However, it is important to have epidemiological information on patients that complements the genomic links, since it is possible that

cases with well-established epidemiological links may escape the pre-established cut-off points75. The study highlights the use of whole genome sequencing in the analysis of XDR-TB strains

circulating in Peru. It is shown that the information obtained allows a high-resolution characterization of severe drug-resistant forms of TB. The use of genomic information would allow a

complete characterization of drug-resistant mutations affecting MTB strains, as well as elucidate transmission links in high-prevalence communities. Furthermore, the incorporation of this

methodology in the routine diagnosis of tuberculosis at the national level would improve the control of tuberculosis and its various drug-resistant forms. CONCLUSIONS This study highlights

the relevance and utility of performing Whole Genome Sequencing as a high-resolution approach to perform genetic analysis of XDR-TB strains circulating in Peru. We performed phylogenomic

analysis based on both SNPs and spoligotypes evidencing the predominance of Lineage 4 through XDR-TB strains circulating in Peru. Also, transmission analysis indicates that the main

mechanism of acquisition of XDR-TB is through failures in the individual treatment of less severe forms of tuberculosis. Finally, the prediction of resistance, determination of transmission

groups, and evolutionary analysis can be effectively evaluated using WGS to improve the understanding of XDR-TB dynamics in these settings and provide precise information to improve control

measures of TB in Peru. STUDY LIMITATIONS The study had the main limitation that only basic epidemiological tracing data were available for all patients whose isolates were included in the

study. Likewise, we were not able to sequence all the XDR-TB strains obtained between the years 2011–2015. We only included viable strains recovered from the Peruvian NIH collection.

Furthermore, due to the size of the sequencing reads obtained, the reliable genotype of the repetitive regions could not be obtained. This limited the analyses to only SNP-like variants that

were not present in these regions. Finally, insertions and deletions (INDELs) were not included in the transmission analyses. It is possible that the omission of these genetic regions and

INDEL-like variants could have masked additional genetic diversity in the samples evaluated. DATA AVAILABILITY All data generated and analysed in the study are included in this article and

its supplementary files. Sequencing reads have been submitted to the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) Sequence Read Archive (SRA) under BioProject ID: PRJNA707145.

REFERENCES * World Health Organization. _Global Tuberculosis Report 2020_. (2020). * World Health Organization. _Global Tuberculosis Report 2019_. (2019). * Günther, G. _et al._

Multidrug-resistant tuberculosis in Europe, 2010–2011. _Emerg. Infect. Dis._ 21, 409–416 (2015). Article PubMed PubMed Central CAS Google Scholar * Matteelli, A., Roggi, A. &

Carvalho, A. C. Extensively drug-resistant tuberculosis: Epidemiology and management. _Clin. Epidemiol._ 6, 111–118 (2014). Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Günther, G. _et

al._ Availability, price and affordability of anti-tuberculosis drugs in Europe: A TBNET survey. _Eur. Respir. J._ 45, 1081–1088 (2015). Article PubMed Google Scholar * Bonilla Asalde,

C. Situación de la tuberculosis en el Perú: Current status. _Acta Méd. Peruana_ 25, 163–170 (2008). Google Scholar * Alarcón, V., Alarcón, E., Figueroa, C. & Mendoza-Ticona, A.

Tuberculosis en el Perú: Situación epidemiológica, avances y desafíos para su control. _Rev. Peruana Med. Exp. Salud Publ._ 34, 299–310 (2017). Article Google Scholar * Rios Vidal, J.

Situación de Tuberculosis en el Perú y la respuesta del Estado (Plan de Intervención, Plan de Acción). http://www.tuberculosis.minsa.gob.pe/portaldpctb/recursos/20180605122521.pdf (2018). *

Soto Cabezas, M. G. _et al._ Perfil epidemiológico de la tuberculosis extensivamente resistente en el Perú 2013–2015. _Rev. Panam Salud Publ._ 44, 1–10 (2020). Article Google Scholar *

Barletta, F. _et al._ Genetic variability of _Mycobacterium tuberculosis_ complex in patients with no known risk factors for MDR-TB in the North-Eastern part of Lima, Peru. _BMC Infect.

Dis._ 13, 397 (2013). Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Capcha, A. L. _et al._ Perfiles genéticos (IS6110) y patrones de resistencia en aislamientos de _M. tuberculosis_ de

pacientes con tuberculosis pulmonar Lima Sur Perú. _Rev. Peruana Med. Exp. Salud Publ._ 22, 4–11 (2005). Google Scholar * Cáceres, O. _et al._ Characterization of the genetic diversity of

extensively-drug resistant _Mycobacterium tuberculosis_ clinical isolates from pulmonary tuberculosis patients in Peru. _PLoS ONE_ 9, e112789 (2014). Article ADS PubMed PubMed Central

CAS Google Scholar * Brown, T. S. _et al._ Genomic epidemiology of lineage 4 _Mycobacterium tuberculosis_ subpopulations in New York City and New Jersey, 1999–2009. _BMC Genom._ 17, 947

(2016). Article CAS Google Scholar * Roetzer, A. _et al._ Whole genome sequencing versus traditional genotyping for investigation of a _Mycobacterium tuberculosis_ outbreak: A

longitudinal molecular epidemiological study. _PLoS Med._ 10, 12 (2013). Article Google Scholar * Walker, T. M. _et al._ Whole-genome sequencing to delineate Mycobacterium tuberculosis

outbreaks: A retrospective observational study. _Lancet Infect. Dis._ 13, 137–146 (2013). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Walker, T. M. _et al._ Whole-genome

sequencing for prediction of _Mycobacterium tuberculosis_ drug susceptibility and resistance: a retrospective cohort study. _Lancet Infect Dis._ 15, 1193–1202 (2015). Article CAS PubMed

PubMed Central Google Scholar * Gilchrist, C. A., Turner, S. D., Riley, M. F., Petri, W. A. & Hewlett, E. L. Whole-genome sequencing in outbreak analysis. _Clin. Microbiol. Rev._ 28,

541–563 (2015). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Niemann, S. _et al._ Genomic diversity among drug sensitive and multidrug resistant isolates of _Mycobacterium

tuberculosis_ with identical DNA fingerprints. _PLoS ONE_ 4, e7407 (2009). Article ADS PubMed PubMed Central CAS Google Scholar * Schürch, A. C. _et al._ The tempo and mode of

molecular evolution of _Mycobacterium tuberculosis_ at patient-to-patient scale. _Infect. Genet. Evol._ 10, 108–114 (2010). Article PubMed Google Scholar * Wood, D. E. & Salzberg, S.

L. Kraken: Ultrafast metagenomic sequence classification using exact alignments. _Genome Biol._ 15, R46 (2014). Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Bolger, A. M., Lohse, M.

& Usadel, B. Trimmomatic: A flexible trimmer for Illumina sequence data. _Bioinformatics_ 30, 2114–2120 (2014). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Li, H. &

Durbin, R. Fast and accurate long-read alignment with Burrows–Wheeler transform. _Bioinformatics_ 26, 589–595 (2010). Article PubMed PubMed Central CAS Google Scholar * Li, H. _et al._

The sequence alignment/map format and SAMtools. _Bioinformatics_ 25, 2078–2079 (2009). Article PubMed PubMed Central CAS Google Scholar * Quinlan, A. R. & Hall, I. M. BEDTools: A

flexible suite of utilities for comparing genomic features. _Bioinformatics_ 26, 841–842 (2010). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * R Core Team. _R: A Language and

Environment for Statistical Computing_. (R. Foundation Statistical Computing, 2019). * McKenna, A. _et al._ The genome analysis toolkit: A MapReduce framework for analyzing next-generation

DNA sequencing data. _Genome Res._ 20, 1297–1303 (2010). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Danecek, P. _et al._ The variant call format and VCFtools. _Bioinformatics_

27, 2156–2158 (2011). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Cingolani, P. _et al._ A program for annotating and predicting the effects of single nucleotide polymorphisms,

SnpEff. _Fly_ 6, 80–92 (2012). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Carver, T., Harris, S. R., Berriman, M., Parkhill, J. & McQuillan, J. A. Artemis: an integrated

platform for visualization and analysis of high-throughput sequence-based experimental data. _Bioinformatics_ 28, 464–469 (2012). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * World Health

Organization. _Technical Guide on Next-Generation Sequencing Technologies for the Detection of Mutations Associated with Drug Resistance in Mycobacterium tuberculosis Complex_. (World Health

Organization, 2018). * Steiner, A., Stucki, D., Coscolla, M., Borrell, S. & Gagneux, S. KvarQ: Targeted and direct variant calling from fastq reads of bacterial genomes. _BMC Genom._

15, 881 (2014). Article Google Scholar * Coll, F. _et al._ A robust SNP barcode for typing _Mycobacterium tuberculosis_ complex strains. _Nat. Commun._ 5, 4812 (2014). Article ADS CAS

PubMed Google Scholar * Xia, E., Teo, Y.-Y. & Ong, R.T.-H. SpoTyping: Fast and accurate in silico Mycobacterium spoligotyping from sequence reads. _Genome Med_ 8, 19 (2016). Article

PubMed PubMed Central CAS Google Scholar * Kozlov, A. M., Darriba, D., Flouri, T., Morel, B. & Stamatakis, A. RAxML-NG: A fast, scalable and user-friendly tool for maximum likelihood

phylogenetic inference. _Bioinformatics_ 35, 4453–4455 (2019). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Darriba, D., Taboada, G. L., Doallo, R. & Posada, D. jModelTest 2:

More models, new heuristics and high-performance computing. _Nat. Methods_ 9, 772 (2012). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Phelan, J. E. _et al._ Mycobacterium

tuberculosis whole genome sequencing provides insights into the Manila strain and drug-resistance mutations in the Philippines. _Sci. Rep._ 9, 9305 (2019). Article ADS PubMed PubMed

Central CAS Google Scholar * Jabbar, A. _et al._ Whole genome sequencing of drug resistant _Mycobacterium tuberculosis_ isolates from a high burden tuberculosis region of North West

Pakistan. _Sci Rep_ 9, 1 (2019). Article CAS Google Scholar * Guerra-Assunção, J. _et al._ Large-scale whole genome sequencing of _M. tuberculosis_ provides insights into transmission in

a high prevalence area. _Elife_ 4, e05166 (2015). Article PubMed Central CAS Google Scholar * Guerra-Assunção, J. A. _et al._ Recurrence due to relapse or reinfection with _Mycobacterium

tuberculosis_: A whole-genome sequencing approach in a large, population-based cohort with a high HIV infection prevalence and active follow-up. _J. Infect. Dis._ 211, 1154–1163 (2015).

Article PubMed Google Scholar * Paradis, E. & Schliep, K. Ape 5.0: An environment for modern phylogenetics and evolutionary analyses in R. _Bioinformatics_ 35, 526–528 (2019). Article

CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Jombart, T., Eggo, R. M., Dodd, P. J. & Balloux, F. Reconstructing disease outbreaks from genetic data: A graph approach. _Heredity_ 106, 383–390 (2011).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Jombart, T. adegenet: A R package for the multivariate analysis of genetic markers. _Bioinformatics_ 24, 1403–1405 (2008). Article CAS PubMed

Google Scholar * Solari, L., Santos-Lazaro, D. & Puyen, Z. M. Mutations in _Mycobacterium tuberculosis_ isolates with discordant results for drug-susceptibility testing in Peru. _Int.

J. Microbiol._ 2020, 8253546 (2020). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Agapito, J. _et al._ Caracterización de las mutaciones en el gen rpoβ asociadas a la rifampicina

en pacientes con tuberculosis pulmonar. _Rev. Peruana Med. Exp. Salud Publ._ 19, 117–123 (2002). Google Scholar * Sandoval, R., Monteghirfo, M., Salazar, O. & Galarza, M. Resistencia

cruzada entre isoniacida y etionamida y su alta correlación con la mutación C-15T en aislamientos de _Mycobacterium tuberculosis_ de Perú. _Rev. Argent. Microbiol._ 52, 36–42 (2019). PubMed

Google Scholar * Farhat, M. R. _et al._ Rifampicin and rifabutin resistance in 1003 _Mycobacterium tuberculosis_ clinical isolates. _J. Antimicrob. Chemother._ 74, 1477–1483 (2019).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Miotto, P., Cabibbe, A. M., Borroni, E., Degano, M. & Cirillo, D. M. Role of disputed mutations in the rpoB gene in interpretation

of automated liquid MGIT culture results for rifampin susceptibility testing of _Mycobacterium tuberculosis_. _J. Clin. Microbiol._ 56, e01599-e1617 (2018). Article CAS PubMed PubMed

Central Google Scholar * Sadri, H., Farahani, A. & Mohajeri, P. Frequency of mutations associated with isoniazid-resistant in clinical _Mycobacterium tuberculosis_ strains by low-cost

and density (LCD) DNA microarrays. _Ann. Trop. Med. Public Health_ 9, 307 (2016). Article Google Scholar * Shaw, D. J. _et al._ Disruption of key NADH-binding pocket residues of the

_Mycobacterium tuberculosis_ InhA affects DD-CoA binding ability. _Sci. Rep._ 7, 1–7 (2017). Article ADS CAS Google Scholar * Ali, A. _et al._ Whole genome sequencing based

characterization of extensively drug-resistant _Mycobacterium tuberculosis_ isolates from Pakistan. _PLoS ONE_ 10, e0117771 (2015). Article PubMed PubMed Central CAS Google Scholar *

Malik, S., Willby, M., Sikes, D., Tsodikov, O. V. & Posey, J. E. New Insights into fluoroquinolone resistance in _Mycobacterium tuberculosis_: Functional genetic analysis of gyrA and

gyrB mutations. _PLoS ONE_ 7, e39754 (2012). Article ADS CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Takiff, H. E. _et al._ Efflux pump of the proton antiporter family confers low-level

fluoroquinolone resistance in _Mycobacterium smegmatis_. _PNAS_ 93, 362–366 (1996). Article ADS CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Louw, G. E. _et al._ A balancing act:

Efflux/Influx in mycobacterial drug resistance. _Antimicrob. Agents Chemother._ 53, 3181–3189 (2009). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Hegde, S. S. _et al._ A

fluoroquinolone resistance protein from _Mycobacterium tuberculosis_ that mimics DNA. _Science_ 308, 1480–1483 (2005). Article ADS CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Luo, T. _et al._ Double

mutation in DNA gyrase confers moxifloxacin resistance and decreased fitness of _Mycobacterium smegmatis_. _J. Antimicrob. Chemother._ 72, 1893–1900 (2017). Article CAS PubMed Google

Scholar * Lin, Y. _et al._ The antituberculosis antibiotic capreomycin inhibits protein synthesis by disrupting interaction between ribosomal proteins L12 and L10. _Antimicrob. Agents

Chemother._ 58, 2038–2044 (2014). Article PubMed PubMed Central CAS Google Scholar * Reeves, A. Z. _et al._ Aminoglycoside cross-resistance in _Mycobacterium tuberculosis_ due to

mutations in the 5′ untranslated region of whiB7. _Antimicrob. Agents Chemother._ 57, 1857–1865 (2013). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Sowajassatakul, A.,

Prammananan, T., Chaiprasert, A. & Phunpruch, S. Overexpression of eis without a mutation in promoter region of amikacin- and kanamycin-resistant _Mycobacterium tuberculosis_ clinical

strain. _Ann. Clin. Microbiol. Antimicrob._ 17, 33 (2018). Article PubMed PubMed Central CAS Google Scholar * Guio, H., Tarazona, D., Galarza, M., Borda, V. & Curitomay, R. Genome

analysis of 17 extensively drug-resistant strains reveals new potential mutations for resistance. _Genome Announc._ 2, e00759-e814 (2014). Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar *

Sowajassatakul, A., Prammananan, T., Chaiprasert, A. & Phunpruch, S. Molecular characterization of amikacin, kanamycin and capreomycin resistance in M/XDR-TB strains isolated in

Thailand. _BMC Microbiol._ 14, 165 (2014). Article PubMed PubMed Central CAS Google Scholar * Stucki, D. _et al._ Mycobacterium tuberculosis Lineage 4 comprises globally distributed and

geographically restricted sublineages. _Nat. Genet._ 48, 1535–1543 (2016). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Brynildsrud, O. B. _et al._ Global expansion of

_Mycobacterium tuberculosis_ lineage 4 shaped by colonial migration and local adaptation. _Sci. Adv._ 4, 5869 (2018). Article ADS Google Scholar * Jiménez, P. _et al._ Identification of

the _Mycobacterium tuberculosis_ Beijing lineage in Ecuador. _Biomedica_ 37, 233–237 (2017). PubMed Google Scholar * Meza, P. _et al._ Presence of Bejing genotype among _Mycobacterium

tuberculosis_ strains in two centres of the Region Metropolitana of Chile. _Rev. Chil. Infectol._ 31, 21–27 (2014). Article Google Scholar * Iwamoto, T. _et al._ Genetic diversity and

transmission characteristics of beijing family strains of _Mycobacterium tuberculosis_ in Peru. _PLoS ONE_ 7, e49651 (2012). Article ADS CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar *

Sheen, P. _et al._ Genetic diversity of _Mycobacterium tuberculosis_ in Peru and exploration of phylogenetic associations with drug resistance. _PLoS ONE_ 8, e65873 (2013). Article ADS CAS

PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Garzon-Chavez, D. _et al._ Population structure and genetic diversity of _Mycobacterium tuberculosis_ in Ecuador. _Sci. Rep._ 10, 6237 (2020).

Article ADS CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Machado, L. N. C. _et al._ First baseline of circulating genotypic lineages of _Mycobacterium tuberculosis_ in patients from the

Brazilian borders with Argentina and Paraguay. _PLoS ONE_ 9, e107106 (2014). Article ADS PubMed PubMed Central CAS Google Scholar * Lagos, J. _et al._ Analysis of _Mycobacterium

tuberculosis_ genotypic lineage distribution in Chile and neighboring countries. _PLoS ONE_ 11, e0160434 (2016). Article PubMed PubMed Central CAS Google Scholar * Realpe, T. _et al._

Population structure among _Mycobacterium tuberculosis_ isolates from pulmonary tuberculosis patients in Colombia. _PLoS ONE_ 9, e93848 (2014). Article ADS PubMed PubMed Central Google

Scholar * Verza, M. _et al._ Genomic epidemiology of _Mycobacterium tuberculosis_ in Santa Catarina, Southern Brazil. _Sci. Rep._ 10, 12891 (2020). Article ADS CAS PubMed PubMed Central

Google Scholar * Díaz Acosta, C. C. _et al._ Exploring the “Latin American Mediterranean” family and the RDRio lineage in _Mycobacterium tuberculosis_ isolates from Paraguay, Argentina

and Venezuela. _BMC Microbiol._ 19, 131 (2019). Article PubMed PubMed Central CAS Google Scholar * Grandjean, L. _et al._ Convergent evolution and topologically disruptive polymorphisms

among multidrug-resistant tuberculosis in Peru. _PLoS ONE_ 12, e0189838 (2017). Article PubMed PubMed Central CAS Google Scholar * Zaman, K. Tuberculosis: A global health problem. _J.

Health Popul. Nutr._ 28, 111–113 (2010). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Luo, T. _et al._ Whole-genome sequencing to detect recent transmission of Mycobacterium

_tuberculosis_ in settings with a high burden of tuberculosis. _Tuberculosis_ 94, 434–440 (2014). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar Download references ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS We express our

thanks to all staff of the NRLM and to the national network of tuberculosis laboratories, for the routine work in the isolation and identification of different strains that were included in

this study. This research was supported by the Peruvian National Institute of Health and the National Program of Innovation for Competitiveness and Productivity (INNOVATE-Peru) under the

contract N° 353-PNICP-PIAP-2014 and the Dirección de Investigación-Universidad Peruana de Ciencias Aplicadas (A-189-2021), Lima-Peru. AUTHOR INFORMATION AUTHORS AND AFFILIATIONS * Instituto

Nacional de Salud, Lima, Peru David Santos-Lazaro, Ronnie G. Gavilan, Lely Solari, Aiko N. Vigo & Zully M. Puyen * Escuela de Medicina, Universidad Peruana de Ciencias Aplicadas, Lima,

Peru Zully M. Puyen * Escuela Profesional de Medicina Humana, Universidad Privada San Juan Bautista, Lima, Peru Ronnie G. Gavilan Authors * David Santos-Lazaro View author publications You

can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Ronnie G. Gavilan View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Lely Solari View author

publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Aiko N. Vigo View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Zully M. Puyen

View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar CONTRIBUTIONS Conceptualization: D.S.L., L.S., R.G.G., A.N.V., Z.M.P.; Formal analysis: D.S.L., R.G.G.,

Z.M.P.; Investigation: D.S.L., L.S., R.G.G., A.N.V., Z.M.P.; Methodology: D.S.L., R.G.G., Z.M.P.; Project administration: Z.M.P.; Original draft preparation: D.S.L., Z.M.P.; Review and

editing: D.S.L., L.S., R.G.G., A.N.V., Z.M.P. The authors read and approved the final manuscript. CORRESPONDING AUTHOR Correspondence to Zully M. Puyen. ETHICS DECLARATIONS COMPETING

INTERESTS The authors declare no competing interests. ADDITIONAL INFORMATION PUBLISHER'S NOTE Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and

institutional affiliations. SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION 1. SUPPLEMENTARY TABLE. RIGHTS AND PERMISSIONS OPEN ACCESS This article is licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original

author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the

article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your

intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence,

visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. Reprints and permissions ABOUT THIS ARTICLE CITE THIS ARTICLE Santos-Lazaro, D., Gavilan, R.G., Solari, L. _et al._ Whole genome analysis

of extensively drug resistant _Mycobacterium tuberculosis_ strains in Peru. _Sci Rep_ 11, 9493 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-88603-y Download citation * Received: 04 December

2020 * Accepted: 14 April 2021 * Published: 04 May 2021 * DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-88603-y SHARE THIS ARTICLE Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read

this content: Get shareable link Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article. Copy to clipboard Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative