Luminescence and photocatalytic degradation of indigo carmine in the presence of sm3+doped zns nanoparticles

- Select a language for the TTS:

- UK English Female

- UK English Male

- US English Female

- US English Male

- Australian Female

- Australian Male

- Language selected: (auto detect) - EN

Play all audios:

ABSTRACT Industrial wastewater discharge is well acknowledged to constitute a significant environmental and public health risk. In addition, synthetic dyes used in the textile sector are

major culprits in water pollution. The amount of water polluted by these dyes is simply staggering. We urgently address this issue to protect our planet and health. The degradation of indigo

carmine dye in the presence of Sm3+-doped ZnS nanoparticles is reported in this study and characterized by XRD, FTIR, SEM, EDX, TEM, BET, PL, UV, etc. The particle size calculated from the

Scherrer equation was 3–12 nm. When excited at 395 nm, Sm3+ undergoes f–f transitions, which are visible as prominent peaks in the photoluminescence spectrum at 559, 595, and 642 nm

wavelengths. The catalyst showed vigorous catalytic activity for dye degradation, with a 93% degradation rate when used at 15 mg/L catalyst within 210 min. The reaction was found to have

pseudo-first-order kinetics. After applying the Freundlich and Langmuir data, the Langmuir isotherm offered the best fit. The findings indicate that the Sm3+-doped ZnS catalyst might be

successfully used in the degradation of dyes present in the environment. Doping with Sm3+ ions can significantly change the photocatalytic breakdown of indigo carmine and the luminescence

characteristics of ZnS. SIMILAR CONTENT BEING VIEWED BY OTHERS PHOTOCATALYTIC DEGRADATION OF METHYLENE BLUE DYE BY ZNO NANOPARTICLE THIN FILMS, USING SOL–GEL TECHNIQUE AND UV LASER

IRRADIATION Article Open access 06 November 2024 SYNTHESIS OF CUO, ZNO NANOPARTICLES, AND CUO-ZNO NANOCOMPOSITE FOR ENHANCED PHOTOCATALYTIC DEGRADATION OF RHODAMINE B: A COMPARATIVE STUDY

Article Open access 27 April 2024 ROLE OF RAW ILMENITE NANOPARTICLES IN RHODAMINE B DEGRADATION USING PEROXYMONOSULFATE AND GRAPHITIC CARBON NITRIDE Article Open access 16 March 2025

INTRODUCTION Dyes and dye-related intermediates, surfactants, and minor metal residues are the chemical pollutants concerned with environmental preservation1,2,3. 10–15% of all dyes are lost

to wastewater during dyeing. Therefore, the effluent must be treated before being released into the environment4,5. Dyes may remain in the water for an extended period, lowering the quality

of the aquatic ecosystem6. Dyes have the potential to pollute the environment due to their chemical makeup, persistence, and negative environmental impacts. These pigments frequently resist

both biological and physical processing methods. Industries, including textile, printing, and papermaking, frequently employ dyes. These companies pollute the water by discharging

wastewater that contains dyes. Fish, algae, and other aquatic life may become poisoned by certain dyes and byproducts of their decomposition. Persistent and poisonous dyes may build up in

the food chain. Animals that consume tainted food or water may collect toxic colour chemicals from humans and other higher-level predators7,8. Some colours may contain toxic heavy metals

like chromium, lead, cadmium, or mercury that can bioaccumulate in the environment. Light penetration and photosynthetic activity decreased as a result of the dyes' severe toxicity and

mutagenicity, which caused an oxygen deficit and restricted downstream beneficial applications, including recreation, drinking water, and irrigation. The textile industry uses toxic

substances that harm the environment and people's health9,10. Advanced oxidation techniques (AOPs) have shown potential for removing dyes from wastewater11. Complete organic matter

mineralization is achievable in the advanced oxidation process (AOPs)12. Fast reaction times and nonselective oxidation are AOP advantages that allow for treating several pollutants

simultaneously13. These pollutants undergo a single breakdown by the OH radical before forming intermediates. As a result of their interaction with the oxidants, those intermediates

transform into stable molecules. The main benefits of photocatalytic degradation include its low operating costs, high rate of target pollutant mineralization, and lack of need for high

pressure and temperature during treatment. Therefore, the removal and degradation of dyes is a growing and important topic of research, which may encourage research efforts to reduce the

environmental issues with textile dye effluents and safeguard the environment14. Additionally, doping semiconductor photocatalysts with a 4f. electron configuration in lanthanide ions might

significantly increase the photocatalytic activity and raise the separation rate of photo-induced charge carriers15,16. Rare earth metals with vacant 4f. and 5d orbitals are widely used to

facilitate catalysis or act as catalysts. Zinc sulfide is a substantial (II-VI) semiconductor with a significant direct band gap of 3.68 eV (bulk)17. Due to its numerous uses as phosphors

and catalysts, ZnS has been researched. Due to its extreme thermal shock tolerance, low bulk losses, and stability in nearly all situations, ZnS is a potential material for solar cells,

electroluminescent devices, and numerous other optoelectronic devices. Due to their potential to increase photocatalytic effectiveness, heterostructures containing zinc sulfide (ZnS)

nanoparticles are a hot topic in photocatalysis. ZnS is a wide-bandgap semiconductor that makes it ideal for photocatalytic applications, including the development of hydrogen and the

degradation of contaminants. A heterostructure's various parts can display various catalytic activities. For instance, ZnS can easily produce electron–hole pairs, whereas another

substance can offer active sites for particular catalytic reactions. An increase in overall photocatalytic activity may result from this synergy. This raises the chances of the charges

taking part in photocatalytic reactions and extends the lifetime of the charges18,19. Because the 3p orbital of the S atom makes up the valence band of metal sulfides, compared to metal

oxides, they feature a complete valence band and a smaller band gap20,21. As a result, metal sulfides, which are visible light-responsive photocatalysts, particularly ZnS and CdS, have

attracted much attention in photocatalysis research. TiO2 also functions as a semiconductor with a significant bandgap (3.0–3.7 eV) when exposed to light with 380 nm wavelengths, which leads

to the formation of electron–hole pairs in redox reactions. When TiO2 is ignited, reactive oxygen species (ROS) are produced, and ROS have the power to oxidize a wide range of organic

compounds in aqueous solutions. When TiO2 and near-UV light are present, these oxidation reactions may convert organic pollutants to carbon dioxide22. It is a fascinating option for

photocatalytic applications due to its high surface-area-to-volume ratio. The increased surface area may address some of the drawbacks of ZnO and TiO2, which can improve photon absorption

and enable more effective separation of photogenerated electron–hole pairs23. In this study, ZnS activity, stability, or selectivity for dye degradation may all be enhanced by adding

samarium (Sm3+). Analysis was also conducted on the effects of operating parameters on the degradation rate, such as pH, catalyst loading, and initial dye concentration. Zinc sulfide (ZnS)

is a semiconductor substance that works well as a photocatalyst. ZnS has a large surface area, which makes more photon absorption sites possible. Light energy can be captured and used for

photocatalytic reactions more effectively. The separation of photogenerated electron–hole pairs dramatically influences the efficiency of photocatalysts. By encouraging the separation of

these charge carriers and lowering the likelihood of recombination, the increased surface area of ZnS can boost the total photocatalytic efficiency24. ZnS is a promising choice for a variety

of photocatalytic applications, including environmental cleanup and solar energy conversion, due to its unique characteristics and high surface area, which may be able to address some of

these restrictions. According to specific research, ZnS is an effective and prospective catalyst for the photocatalytic elimination of organic pollutants16,25,26. In order to eliminate toxic

dyes that are present in the environment, this study will offer new strategies for researchers. As far as we know, research has yet to be published on the photocatalytic degradation of

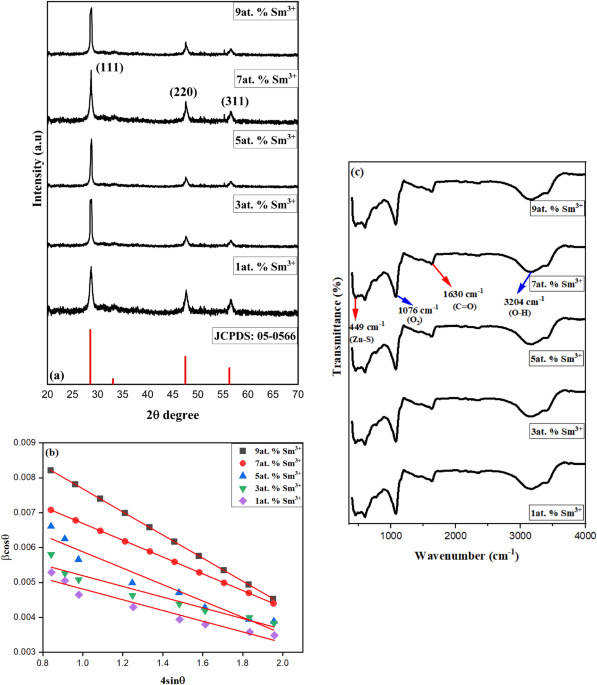

indigo carmine by Sm3+-doped ZnS nanoparticles. This paper introduces a straightforward reflux approach for synthesising Sm3+-doped ZnS nanoparticles. RESULTS Figure 1a confirms the XRD

cubic zinc ZnS structure (JCPDS No. 05-0566) with the lattice parameters and volume given in Table 1. When the amounts of Sm3+ doping increased, the nanoparticle crystallinity also

increased. The diffraction peaks of Sm3+-doped ZnS exhibit a slight shift towards higher 2θ values. The synthesized materials exhibited distinct diffraction peaks, demonstrating the sample

crystallinity. Using Scherrer’s formula, the average particle size was calculated using the formula D = (Kλ)/β cosθ, where ‘K’ is constant (0.9) and the wavelength of X-rays employed ‘λ’

(1.5406 Å)27. According to the Scherrer equation, Sm3+-doped ZnS nanocrystals have a 3–12 nm particle size. Furthermore, the experimental results show that the broadening for small

crystallites is distinct from the strain-induced broadening. Therefore, the full-width half maximum (FWHM) of the XRD pattern provided in the equation may be calculated using the linear sum

of the FWHMs of size, strain, and instrument28: $$\upbeta _{{{\text{tot}}}} = {\upbeta }_{{{\text{size}}}} +\upbeta _{{{\text{strain}}}} +\upbeta _{{{\text{instrument}}}}$$ (1) Here, the

instrument broadening βhkl was adjusted by each diffraction peak, and a Lorentzian profile was fitted. Strain broadening is the term used to describe the contribution of lattice strain to

peak broadening, which is often caused by local deformation of the lattice. If the strain is taken to be constant throughout all crystallographic orientations and the crystal is isotropic,

the strain broadening can be depicted as follows29: $$\upvarepsilon =\upbeta _{{{\text{hkl}}}} /4\tan\uptheta .$$ (2) Substituting values of βsize and βstrain in the above equation:

$$\upbeta _{{{\text{hkl}}}} = {\text{K}}\uplambda /{\text{D}}\cos\uptheta + 4\upvarepsilon .$$ (3) The above Eq. (3) can be rearranged by: $$\upbeta _{{{\text{hkl}}}} \cos\uptheta =

{\text{K}}\uplambda /{\text{D}}\cos\uptheta + 4\upvarepsilon \sin\uptheta .$$ (4) The parameter of the micro-strain is $$\upvarepsilon = \Delta {\text{D}}_{{{\text{hkl}}}}

/{\text{D}}_{{{\text{hkl}}}} .$$ (5) A graph is drawn between 4 sinθ and βhkl cosθ, as shown in Fig. 1b For the samples corresponding to 1, 3, 5, 7, and 9 at. % the micro-strain calculated

from the graph is -0.0331, -0.0241, -0.0235, -0.0154, and -0.0164, respectively. The R2 values for different concentrations were also found to be 0.982, 0.973, 0.955, 0.942, and 0.933.

Williamson-Hall plots of samples show a negative slope, which denotes the particle’s compressive strain. Figure 1c displays the synthesized Sm3+-doped ZnS FTIR spectra at 1, 3, 5, 7, and

9at.%. This demonstrates the capability of infrared spectroscopy to recognize the sample's functional groups. IR spectroscopies, which depend on the absorption of infrared light, are

used to determine the vibrational energy of molecules30. A massive peak of 3204 cm−1, which was most likely caused by the adsorptive moisture on the surfaces of the materials, was attributed

to the stretching of the –OH. This peak may indicate adsorptive moisture on the material's surface since it indicates the existence of hydroxyl (alcohol) functional groups in the

substance. The significant peaks detected around 1630 cm−1 can also be attributed to the carboxyl (C=O) stretching vibration because the functional group is present in the adsorbed

residues31. This suggests that the adsorbed residues contain carboxylic acid or ester groups. The peak seen at 1076 cm−1 is caused by oxygen (O2). It can be a reference peak or show that the

substance contains oxygen-containing functional groups. The usual ZnS primary bonding peak (Zn–S stretching or lattice vibrations) is seen at 449 cm−1. The primary bonding in ZnS is linked

to the peak at this wavenumber. It is frequently related to lattice vibrations or Zn–S stretching and can be used to identify whether ZnS is present in the material. SEM images and relative

EDX spectra of 9at. % Sm3+-doped ZnS samples are shown in Fig. 2a,b. According to their morphology and microstructure, the samples are composed of various agglomerated particles that are

largely irregular, non-uniform, and spherical. The term "agglomeration" describes the clustering or gathering of different particles. Since the samples are made up of various

aggregated particles, it is clear that the zinc sulfide-doped samarium particles tend to collect rather than distribute evenly. The particles are described as having an erratic shape. This

shows that the particles' shapes need to be more homogeneous and clearly defined. They might have uneven edges or rough surfaces as a result of many things, such as the synthesis

process or the growth environment. The particles have a spherical form in addition to being classified as irregular. The synthesis technique, temperature, pressure, and other processing

variables can all have an impact on the zinc sulfide doped with samarium's observable morphology and microstructure. The samples contain zinc, sulfide, and samarium elements, confirmed

by the energy-dispersive X-ray examination. Atomic and weight percentages from the EDX are displayed in Table 2. The samples had an average size diameter of 5.15 nm, as shown in Fig. 2c.

Figure 2d displays a TEM image of Sm3+-doped ZnS 9at. %. The estimated particle size from the TEM image was spherical as well as rod-shaped was found to be 5 nm. The nanometer (nm) range of

this size measurement suggests that the sample's particles are quite small. The particles were both spherical and rod-shaped. Various synthesis processes or the presence of various

crystallographic phases may have resulted in the coexistence of distinct particle morphologies. Especially in fields like catalysis, optics, and materials science, the size and form of

nanoparticles can significantly affect both their characteristics and uses. Their size and form, as well as their crystalline structure and dopant dispersion, can all be affected by the

precise synthesis process and conditions used to create these nanoparticles. Figure 2e displays the SAED patterns of Sm3+-doped ZnS nanoparticles as well as the locations of the three

diffraction rings, which are the same as those seen in the (111), (220), and (311) diffraction of bulk ZnS32. From the selected area electron diffraction (SAED) pattern, the d-spacing is

calculated. The first ring is 2.0 Å, the second is 1.6 Å, and the third is 1.2 Å. The Brunauer Emmett Teller (BET) method is popular for calculating a particular surface area. The two

primary factors in photodegradation are the vast surface area and the small particle size. Figure 3 shows the Sm3+-doped ZnS N2 absorption–desorption observations at 1, 3, 5, 7, and 9 at.%.

The produced samples displayed type-IV H1 hysteresis loop isotherms, indicating mesoporous. Mesoporous (2 nm < pore size < 50 nm) materials produce the type IV isotherm33. The

BET-specific surface areas were 54 m2/g, 72 m2/g, 88 m2/g, 113 m2/g, and 129 m2/g for 1, 3, 5, 7, and 9 at.% samples, respectively. The results of this BET analysis showed that Sm3+-doped

ZnS 9at. % nanoparticles with large surface areas could efficiently promote electron and ion movement at the interface to improve dye degradation performance. This is a crucial observation

because more active areas for chemical reactions exist when a surface area is more significant. The increased surface area of the Sm3+-doped ZnS nanoparticles promotes effective electron and

ion transport at the interface between the nanoparticles and the dye molecules. The performance of dye degradation is improved due to the higher electron and ion movement34. The electrical

structure and surface characteristics of the ZnS nanoparticles are probably affected by the Sm3+- dopant, which makes them better suited to enhanced electron transfer and facilitates the

degrading process. Overall, the BET study shows that Sm3+-doped ZnS nanoparticles have properties that make them suitable catalysts for degrading dyes. Nanoparticles have proven to be highly

effective in various applications, including dye degradation. This is mainly because nanoparticles possess a large surface area, enabling more efficient reactions. In addition, dopants like

Sm3+ further enhance their performance, leading to superior results. Figure 4a shows Sm3+-doped ZnS 1, 3, 5, 7, 9at. % emission peaks for photoluminescence spectra, which were measured

between 500 and 700 nm. When excited at 395 nm, the peak positions are found to increase with an increase in Sm3+ concentrations up to 5 at. % and then decrease with a further increase in

Sm3+ concentration, caused by the concentration quenching effect of Sm3+ induced by cross-relaxation. With increasing dopant concentration, there are more non-radiative transition events

where energy is transferred from the initially absorbing impurity ions to comparable ions. A transfer to a quenching site (defect) may get implicated after many of these steps, further

reducing the radiative process. Significant peaks in the emission spectra can be seen at wavelengths 559 nm (4G5/2 → 6H5/2), 595 nm (4G5/2 → 6H7/2), and 642 nm (4G5/2 →6H9/2), which

correspond to the f-f transitions of Sm3+ in the 4f5 configuration, respectively. According to the selection rule, the peak at 559 nm (4G5/2 → 6H5/2) resulted from a pure dipole transition

between an electric dipole (ΔJ = ± 2) and a magnetic dipole (ΔJ = 0 and ± 1). While the transition (4G5/2 → 6H7/2) observed at 595 nm satisfies the selection rule for the magnetic dipole

transition, it is attributed to the partially electric dipole and partially magnetic dipole transitions, whereas the electric dipole transition predominates. The peak (4G5/2 → 6H9/2) at 642

nm results from an electric dipole transition35,36,37. The impact of the crystal field on the transition between pure electric dipoles is significant indeed. It is also fascinating how it

affects the transition between two pure electric dipoles. The Judd–Ofelt theory can be used to explain the local site symmetry around Ln3+ in a matrix38. Exception to their intensities, the

peak profiles did not vary when Sm3+ concentrations changed, showing that Sm3+ had the exact site symmetry at all concentrations. Figure 4b displays the excitation spectra for the

as-prepared Sm3+-doped ZnS 1, 3, 5, 7, and 9at. % obtained by monitoring when emitted at 615 nm. The spectra comprise a broad band between 350 and 550 nm. The electronic transition from Sm3+

ground state (6H5/2) to various excited energy levels produces spectra with sharp, narrow peaks. They can be positioned at 367 nm (6H5/2 → 6P7/2), 401 nm (6H5/2 → 4F7/2), 439 nm (6H5/2 →

6P5/2), 476 nm (6H5/2 → 4G9/2), and 501 nm (6H5/2 → 4I13/2). Due to Sm3+ f-f transitions, it can be seen that the broad absorption band's intensity is more significant than those narrow

peaks, indicating that energy has been transferred from the host lattice to Sm3+39. These results agree with the earlier publications on the photoluminescence features of Sm3+40,41. The

luminescence properties of ZnS are changed by doping with Sm3+ ions, which introduce luminous centers into the crystal structure. The characteristic energy level transition in Sm3+ ions

results in luminescence at particular wavelengths. The excitation wavelength, Sm3+ doping concentrations, and luminescence intensity of Sm3+ doped ZnS will all affect the emission spectra

and luminescence intensity. Applications for the luminescence produced by Sm3+ doped ZnS include optoelectronics, display technology, luminescence devices, etc16. For applications involving

photoluminescence, CIE colour coordinates are important. Figure 4c Displays the CIE chromaticity curve for synthesized Sm3+-doped ZnS at 1, 3, 5, 7, and 9at. %. This diagram showed that when

triggered at 395 nm, the generated samples emit a hue that is almost entirely white hue. Figure 4d shows the emission decay curves for Sm3+-doped ZnS samples at 1, 3, 5, 7, and 9at. %. The

bi-exponential function can be used for precisely fitting the entire decay curve as given in Eq. (6)42: $${\text{I}} = {\text{I}}_{1} \exp \left( { - {\text{t}}/\uptau _{1} } \right) +

{\text{I}}_{2} \exp \left( { -\uptau /\uptau _{2} } \right).$$ (6) I1 and I2 represent the equivalent decays of intensities at two different points in time ‘t’. It displays the values of two

lifetimes: slow time τ2 and quick time τ1. The key variables influencing the behaviour of bi-exponential decay are the number of luminescence centers, energy transfer from the donor, the

unequal distribution of dopant ions on the host lattice, and impurities. I1 and I2 represent equivalent decays of intensities at different points in time 't'. The values of slow

time τ2 and quick time τ1 play a crucial role in determining the behavior of bi-exponential decay. Factors such as the number of luminescence centers, energy transfer from the donor, unequal

distribution of dopant ions on the host lattice, and impurities can also impact the behavior of bi-exponential decay. The typical luminescence lifespan can be calculated using the following

equation43. $$*\uptau = I_{1}\uptau _{1}^{2} + I_{2}\uptau _{2}^{2} /I_{1}\uptau _{1}^{2} + I_{2}\uptau _{2}$$ (7) The calculated average life times of Sm3+-doped ZnS at concentrations 1,

3, 5, 7, 9at. % were found to be 1.88, 1.71, 1.89, 1.52, 1.49 ms respectively. According to speculation, the concentration quenching effect is what causes the life time value to decrease

with increasing Sm3+ concentration. Nanocatalyst doses ranging from 5 to 30 mg/L are exposed to light for 210 min. Due to an increase in active sites, the rate of decolourisation increases

to its maximum degrading efficiency in the presence of 15 mg/L of nano-photocatalyst. However, as the loading was increased above the optimal level, the decolourisation rate was reduced due

to the increased opacity of the suspension samples and, as a result, increased light scattering, as seen in Fig. 5a. The pH range where the solution can degrade indigo carmine was found to

be 5.3. A diluted hydrochloric acid or potassium hydroxide solution was used to modify the pH value when necessary. Different solutions were created with pH values ranging from 1, 3, 5, 7,

9, and 11. Following 210 min of photocatalytic irradiation, the degradation efficiencies were examined. The effectiveness of the indigo carmine solution's degradation decreased as the

pH level of the reaction solution increased, as shown in Fig. 5b. When the pH was 5, degradation efficiency was higher, but when it was 11, it reduced to 30.45%, indicating that the optimal

pH for degradation was found to be pH 5. Since indigo carmine is a synthetic dye, its stability and chemical properties, like those of many other dyes, may be pH-dependent. The dye molecule

may be more vulnerable to breakdown at pH 5 due to several mechanisms, including hydrolysis, oxidation, or reduction. The dye molecule may be more likely to degrade at this ideal pH. Indigo

carmine can be broken down more quickly at pH 5 because some enzymes or catalysts may be more active at that level. The dye may be more soluble or more likely to form aggregates more

vulnerable to deterioration processes. The molecule may be more prone to photodegradation, where light energy triggers chemical processes that result in dye deterioration. Dye solutions have

been produced in concentrations ranging from 10 to 40 (ppm). 10 ppm shows the best degradation percentage. The decreasing efficiency decreased as the starting concentration rose, as

indicated in Fig. 5c, and the tendency accelerated as the concentration increased. As the concentration increased, more photons would be absorbed, limiting light transmission. As a result,

less light was able to penetrate deeply, limiting the nanoparticle's potential to catalyze the processes. The ability of a chemical to deteriorate at varied doses over time was

investigated. Figure 5d shows the indigo carmine degradation in 210 min at pH 5 with concentrations of 10 ppm and 15 mg/L of catalytic dose. Indigo carmine absorbs the most light in the

visible spectrum at a wavelength peak of 615 nm. Indigo carmine absorbs some wavelengths of visible light and reflects or transmits others when it is in contact with the light. In this

instance, it primarily absorbs light in the blue and green portions of the spectrum, giving it a blue hue. The absorption at 615 nm is defined by the conjugated system of aromatic

rings' molecular structure and electronic transitions. The energy needed to move molecules electrons from their lower-energy (ground) states to their higher-energy (excited) states is

represented by this absorption peak. Figure 5e provides information on the structure of indigo carmine and the potential degradation mechanism. The photocatalytic performance of ZnS for the

degradation of dyes concerning this work is given in Table 3. Dye degradation is a systematic process with a well-defined course and intuitive mechanism. ZnS has an energy band structure

with a low valence band (VB) filled with electrons and a high empty energy conduction band (CB). It has been demonstrated that when the energy of the radiation exceeds the band gap width of

ZnS, matched holes (h+) grow in the valence band (VB), creating a “electron hole” pair. In contrast, excited electrons in the valence band (VB) can jump into the conduction band (CB)44.

According to Eqs. (8–14), superoxide ions (O2⋅) are created when absorbed oxygen (O2) and conduction band electrons (CB) interact under the conditions of irradiation. These reactive oxygen

species (O2⋅, OH⋅, and H2O2) have an exceptionally high redox capacity along the whole photocatalytic reaction pathway. They are capable of breaking down large organic molecules into smaller

molecules, more environmentally friendly molecules like CO2 and H2O. In order to speed up chemical reactions that break down dye molecules, photocatalytic degradation of dyes uses light to

activate catalyst materials. The bandgap energy of the catalyst material may change due to doping. Doping enables the material to absorb a wider range of light, including visible light, by

reducing the bandgap. The photocatalytic process depends on the photogenerated electron–hole pairs' recombination rate, which doping can lower. Reduced recombination means that more of

these charge carriers can interact with dye molecules in redox processes, which increases the effectiveness of dye degradation. Dopant atoms can increase the number of active sites and

change the catalyst's surface characteristics, facilitating dye molecule adsorption and subsequent reactions. More dye molecules may interact with the catalyst's active sites as a

result, increasing catalytic activity. The degradation of indigo carmine using pure, 1, 3, 5, 7 and 9 at.% is shown in Fig. 5f, and it demonstrates that 9at.% was the best for dye

degradation, demonstrating the significant influence that doping has on photocatalytic activity. Doping a catalyst can considerably boost its performance in dye degradation, particularly in

photocatalysis, by extending its light absorption range, boosting charge separation and transport, increasing active sites for adsorption, and fine-tuning. These advancements are essential

for wastewater treatment and environmental remediation procedures that are more effective and sustainable. The nanoparticles' yield as a percentage was above 88%. The highest yield is

achieved at 9 at. %; it also demonstrates a greater advantage in the degradation of nanoparticles and is most effective in the degradation of indigo carmine. The purity of the starting

ingredients, the effectiveness of the synthesis process, and the methods used for purification can all impact on the yield of nanoparticles. Due to the difficulties in regulating and

isolating nanoparticles in a highly pure state, nanoparticles frequently have lower yields than bulk materials. The abovementioned processes demonstrate that photocatalytic degradation is

possible when soluble oxygen and H2O are present. There have been other reports of similar methods for the photocatalytic destruction of dyes44. As a result, ZnS nanoparticles have the

potential to purify them, which causes photocatalysis to destroy indigo carmine dye. The photodegradation mechanism is represented by the following steps: $${\text{ZnS}} + {\text{h}}\upnu

\to {\text{e}}^{ - } + {\text{h}}^{ + }$$ (8) Zinc sulfide (ZnS) absorbs light energy (hѵ) and undergoes photoexcitation. This process generates an electron (e−) and a positive hole (h+).

$${\text{e}}^{ - } + {\text{O}}_{2} \to {\text{O}} \cdot _{2}^{ - }$$ (9) The generated electron (e−) reacts with oxygen (O2) to form superoxide anion (O·2−). $${\text{O}}_{2}^{{ \cdot - }}

+ {\text{h}}^{ + } \to {\text{HO}} \cdot _{2}$$ (10) The positive hole (h+) reacts with superoxide anion (O·2−) to form hydroperoxyl radical (HO⋅2). $${\text{HO}}_{{ \dot 2}} + {\text{e}}^{

- } \to {\text{h}}^{ + } \to {\text{H}}_{2} {\text{O}}_{2}$$ (11) The hydroperoxyl radical (HO⋅2) reacts with the generated electron (e−) to form a positive hole (h+), leading to the

production of hydrogen peroxide (H2O2). $${\text{H}}_{2} {\text{O}} + {\text{e}}^{ - } \to {\text{OH}}^{ \cdot } + {\text{OH}}^{ - }$$ (12) Water (H2O) reacts with the generated electron

(e−) to produce hydroxyl radical (OH⋅) and hydroxide ion (OH−). $${\text{h}}^{ + } + {\text{OH}}^{ - } \to {\text{OH}}^{ \cdot }$$ (13) The positive hole (h+) reacts with hydroxide ion (OH−)

to form hydroxyl radical (OH⋅). $${\text{OH}}^{ \cdot } /{\text{O}}_{2}^{ - } + {\text{Indigo}}\;{\text{carmine}}\;{\text{dye}} \to {\text{degradation}}\;{\text{products}}$$ (14) Hydroxyl

radicals (OH⋅) or superoxide anions (O·2−) react with Indigo carmine dye, leading to the degradation of the dye and the formation of various degradation products. Figure 5g shows the UV–Vis

absorption spectra of different atomic percentages. The energy of the band gap (Eg) of ZnS nanoparticles can be calculated from the UV–Vis spectra by creating a Tauc plot of (hѵα)2 versus

(hѵ) and extrapolating the linear portions of the curves to the energy axis: $$\alpha h\nu = B\left( {h\nu {-}Eg} \right)^{1/2}$$ where _Eg_ is the direct band gap energy, _hѵ_ is the photon

energy,_ α_ is the absorption coefficient, and _B_ is a constant. The calculated bandgap was found to be 4.25, 4.01, 3.90, 3.78 and 3.72 eV for 1, 3, 5, 7, and 9 at.% respectively.

Depending on the concentration and type of doping, adding samarium (Sm3+) to zinc sulfide (ZnS) might change its bandgap. Samarium can introduce energy levels within the bandgap by

increasing doping concentrations, effectively reducing the bandgap. This process is referred to as “bandgap narrowing”. Samarium introduces impurity states in these conditions, decreasing

the energy required for electron excitation and facilitating electron migration from the valence band to the conduction band. Samarium concentration and material crystal structure will

determine the exact impact on the bandgap. An adsorption isotherm describes the relationship between the amount of dye adsorbed by the adsorbent at equilibrium and the equilibrium dye

concentration in the solution. For assessing the viability of the adsorption process as a single operation, adsorption equilibrium provides essential physiochemical information. This

isotherm accounts for the effects of numerous dye/adsorbent interactions that are indirect, and it predicts that these interactions will cause a linear reduction in the heat of adsorption

with increasing molecule-by-molecule coverage of the layer. Adsorption equilibrium gives critical physiochemical data for assessing the adsorption process's applicability as a single

operation. The Freundlich and Langmuir isotherm models examined the relationship between solution concentration and dye adsorption. The isotherm's best fit was determined using a linear

regression value48. Freundlich Isotherm: The adsorption on heterogeneous surfaces is explained by this isotherm, and the data frequently suit the provided equation49,50. $$q_{e } = K_{f}

C_{e} \frac{1}{n}$$ (15) The Freundlich isotherm has the following logarithmic form: $$\log q_{e} = \log K_{f} + \frac{1}{n}\log C_{e}$$ (16) The equilibrium amount of dye adsorbed per gram

of adsorbent is indicated by _q__e_ (mg/g), and the equilibrium adsorbate concentration is denoted by the symbol _C__e_ (mg/L). The slope and intercept of the line shown in Fig. 6a can be

used to determine the sorption intensity (g/L), or 1/n and \(K_{f}\) (Freundlich constant) where R2 was found to be 0.922. Langmuir Isotherm: The equation can be used to calculate this

isotherm, which provides data on the production of monolayers on homogeneous surfaces: $$q_{e} = \frac{{K_{L} C_{e} }}{{1 + aLC_{e} }}.$$ (17) The equation can be written as follows in

linearized form: $$\frac{{ C_{e} }}{{ q_{e} }} = \frac{1}{{K_{L} }} + \frac{{aLC_{e} }}{{K_{L} }}$$ (18) Langmuir isotherm constants are K_L_ and a_L_; the concentration at equilibrium

(mg/L) is represented by \(C_{e}\); _q__e_, which is the adsorbed amount (mg/g), K_L_/a_L_ is the numerical equivalent of the theoretical monolayer capacity (Qo). C_e_/_qe_ versus C_e_ was

used to depict the Langmuir adsorption isotherm and a line with a 0.998 R2 correlation coefficient was found given in Fig. 6b. Table 4 shows the calculated parameters for the Langmuir and

Freundlich isotherm models. The Langmuir isotherm model may be the best-fitting model for the sorption of indigo carmine dye, according to the estimated correlation value R2 shown in Table

4. The primary step in many separation and purification procedures is adsorption. The molecules or ions from a solution adhere to the surface of a solid or liquid adsorbent. Mathematical

representations known as kinetic models are used to explain the adsorption rate. It is predicated on the idea that the rate of adsorption is inversely proportional to the solute

concentration. In other words, the rate of adsorption increases with increasing solute concentration. The pseudo-first-order model may not be applicable in all situations but is appropriate

for a system where adsorption is largely a physical process. Another kinetic model used to describe adsorption is the pseudo-second-order model. It is predicated on the idea that the

adsorption rate is inversely proportional to solute concentration squared. This model can better fit systems where adsorption involves chemical interactions between the solute and the

adsorbent when dealing with heterogeneous sorbents and chemical sorption. Experimental data on the degradation of indigo carmine is gathered and analyzed using these models to shed light on

the adsorption mechanism and validate the kinetic models. The system will influence model selection under study, the type of adsorption, and the adsorbent's characteristics. The

pseudo-first-order equation is expressed as51: $$\log \left( {qi - qt} \right) = log_{qe} - \frac{{k_{1} }}{2.303}t$$ (19) And _q__e_ is the catalyst amount (mg/g) at equilibrium. _q__t_ is

the catalyst quantity (mg/g) at any given time (min−1), _q__e_ is the catalyst quantity (mg/g) at equilibrium, and _k_1 is the first-order reaction rate constant. The pseudo-second-order

model is based on the hypothesis that chemisorption, which involves valence forces through the sharing or exchange of electrons between adsorbent and adsorbate, may be the rate-limiting

phase. The pseudo-second-order equation is represented as follows52,53,54: $$\frac{t}{{q_{t} }} = \frac{t}{{q_{e} }} + \frac{1}{{kq_{e}^{2} }}$$ (20) The catalyst amount (mg/g) at a specific

time (min−1) is given by _q__t_, _q__e_ is the catalyst amount (mg/g) at equilibrium, and _k_2 is the pseudo-second-order reaction rate constant. The rate constant for the first order

kinetic (_k_1) was calculated using a linear plot of time (_t_) vs. log (_q__e_–_q__t_), where _q__e_ and _q__t_ represent the quantity of dye adsorbed (mg/g) at equilibrium and time (t),

respectively. The second-order kinetic (k2) rate constant was calculated using the linear time vs. _t/qt_ plot shown in Fig. 7a,b. Table 5 shows the rate constant and R2 values, which follow

pseudo-first-order kinetics. The pseudo-first-order kinetic model's R2 value is considerably more significant than the second-order kinetic model's. As a result, the adsorption of

indigo carmine dye using Sm3+-doped ZnS nanoparticles is well correlated using the pseudo-first-order kinetic model. As a result of the repeated usage of nanophotocatalysts for the

degradation of indigo carmine dye, the reusability of the catalysts has been studied, as shown in Fig. 8. The results show that reusability is good for up to five consecutive cycles. The

nanophotocatalyst was collected by filtration after the first photodegradation cycle. After being thoroughly cleaned with deionized water, it was dried in an oven for an entire night at room

temperature. The experiment was conducted both in the presence of UV and visible light. It clearly shows that in UV light, photocatalytic degradation decreases from 93 to 65%, and in

visible light, it decreases from 89 to 64%. The photocorrosion effect is the cause of this decline in photocatalytic effectiveness. A material oxidatively degrades in the presence of light,

which is known as the photocorrosion effect. Under UV light and sunlight, ZnS undergoes photocorrosion. CONCLUSION In this study, the focus was on the synthesis and characterization of Sm3+

doped ZnS nanoparticles using the reflux method. The research team investigated several properties of the nanoparticles, including kinetics, structural, chemical, optical, isotherms,

luminescence, and photocatalytic properties. The results indicated that Sm3+ doping had a positive impact on the luminescence and photocatalytic properties of the ZnS nanoparticles. The

maximum photocatalytic activity has been observed in 9 at% Sm3+-doped ZnS nanoparticles, which were used for further evaluation. The best optimum parameters for removing dye were found to be

15 mg/L of catalyst, 210 min of reaction time, pH 5, and an initial concentration of 10 ppm. All the synthesized samples exhibited a zinc cubic phase, as observed in the XRD pattern. The

average particle size calculated from the SEM image was found to be 5.15 nm. According to photoluminescence studies, when excited at 395 nm, the emission spectra can be seen at wavelengths

559 nm (4G5/2 → 6H5/2), 595 nm (4G5/2 → 6H7/2), and 642 nm (4G5/2 →6H9/2), which correspond to the f-f transitions of the Sm3+ in the 4f5 configuration, respectively. The results of CIE

diagram showed that the nanoparticles can be highly useful for photonic applications. Five catalyst runs could be successfully retrieved without the catalyst experiencing a significant loss

of activity. The reaction had pseudo-first kinetics, and the Langmuir model best matched the isotherm data. As a result of improved charge separation and decreased recombination, Sm3+-doped

ZnS can increase the photocatalytic degradation efficiency of indigo carmine. Overall, the study suggests that Sm3+-doped ZnS nanoparticles can be an effective and promising method for

removing coloured effluents, with significant potential for reusability and luminescent applications. METHODS Sodium sulfide (98.0% purity) Na2S·9H2O Alfa-Aesar, zinc acetate dihydrate

(98.0–101.0% purity) Alfa Aesar (CH3COO)2 Zn·2H2O, and Samarium(III) nitrate hexahydrate (99.9% purity) Sm(NO3)3.6H2O Alfa-Aesar were used in the reflux method to synthesize the

nanoparticles of Sm3+ doped ZnS. PROCEDURE Sm3+-doped zinc sulfide nanoparticles with varying concentrations (1, 3, 5, 7, and 9at. %) were synthesized using the reflux process. Samarium and

ZnS were mixed and stirred at room temperature for 45 min. Drop by drop, sodium sulfide was added to the aforementioned solution. The entire solution was then refluxed at 160 °C for three

hours. The resultant residue was washed with acetone, centrifuged at 7000 rpm and dried at 100 °C for 5 h. Various doping concentrations of Sm3+ doped zinc sulfide nanoparticles were

synthesized using the same process. FORMATION OF NANOPARTICLES Samarium is incorporated as a dopant into the ZnS lattice by carefully adding samarium nitrate to the zinc precursor solution.

The doping concentration is determined by the amount of samarium introduced, and it can be adjusted to modify the characteristics of the nanoparticles. The reaction is usually conducted at

elevated temperatures under controlled conditions using a mixture of zinc and sulfur precursor solutions. As a result, ZnS nanoparticles start to form. During the nucleation process, the

doped samarium ions are integrated into the ZnS lattice, creating Sm3+-doped ZnS nanoparticles. The nanoparticles keep expanding as the reaction goes on. Stabilizing agents or surfactants

may be applied to manage the nanoparticles' size, shape, and aggregation. The reaction mixture is removed from the Sm3+-doped ZnS nanoparticles, frequently by centrifugation or

filtration, and the nanoparticles are cleaned and purified to get rid of any unreacted precursors or byproducts. CHARACTERIZATION Different characterization techniques were used to

characterize the prepared samples. Using Rigaku SmartLab, the crystal structure and phase composition were discovered using XRD. The SEM image was obtained using a Carl Zeiss Supra 55 FESEM.

Using the FEI TECNAI G2 F20 S-TWIN, TEM images were captured. Shimadzu's IRAffinity-1S was used to collect FTIR data. A fluorescence spectrometer F-7000 with a (150 W) Xenon lamp was

used to evaluate the photoluminescence characteristics. Novatouch LX Quantachrome was used to collect BET data. A wavelength range of 190 to 1100 nm evolution 220 UV visible

spectrophotometer was used to evaluate the photocatalytic properties. PHOTOCATALYTIC DEGRADATION PROCEDURE AND ANALYSIS The photocatalytic activity was investigated by observing the

photodegradation of indigo carmine. Different dye concentrations (between 10 and 40 ppm) with catalytic doses (5–30 mg/L) and pH ranges (1, 3, 5, 7, and 11) were studied. Each reaction was

stirred with a magnetic stirrer for 60 min to ensure that the catalyst suspension was uniform throughout the reaction for the degradation tests and exposed to UV light Philips PL-S 92/WP

BLB. Samples were taken regularly, filtered using Millipore membrane filters, and centrifuged to get rid of any undissolved materials to calculate the percentage of dye degradation. A small

amount was extracted with a syringe and filtered through a 0.45 mm hole millipore syringe filter. The composite nanoparticles were repeatedly cleaned with distilled water after each

experiment in order to allow for reuse. Using a UV–visible spectrophotometer, the UV absorbance in the 200–700 nm region was recorded at certain intervals (every 30 min), and the dye

concentration was then calculated. Accordingly, the photodegradation efficiency was determined using the formula 51: The photodegradation efficiency was calculated using the formula provided

in the text, which considers the starting concentration of the dye and the concentration at a given time. UV–visible spectrophotometer was used to measure the UV absorbance in the 200–700

nm region at specific intervals of 30 min, and the dye concentration was calculated accordingly. This allowed for the determination of the photodegradation efficiency of the composite

nanoparticles. The formula used for this calculation was efficiency (%) of photodegradation = (Ci − Ct)/Ci × 100, where Ci is the starting concentration of the dye and Ct is the

concentration at time ‘t’. By evaluating the photodegradation efficiency, the durability and usability of the photocatalytic catalysts were determined. $${\text{Efficiency}}\;\left( \%

\right)\;{\text{of}}\;{\text{photodegradation:}}\;\frac{{C_{{i - }} C_{t} }}{{C_{i} }} \times 100$$ where \(C_{i}\) denotes the starting concentration and \(C_{t}\) denotes the concentration

at time ‘t’. After each cycle of degradation, the photocatalytic catalyst's durability and usability were evaluated. The catalyst was filtered out and repeatedly rinsed with distilled

water before the dyes were photodegraded under the same circumstances. DATA AVAILABILITY Data are available from the authors upon reasonable request and with the permission of the

corresponding author. ABBREVIATIONS * XRD: X-ray diffraction * FTIR: Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy * SEM: Scanning Electron Microscopy * SAED: Selected area electron diffraction *

EDX: Energy dispersive X-ray analysis * TEM: Transmission electron microscopy * BET: Brunauer–Emmett–Teller * PL: Photoluminescence * UV: Ultraviolet spectroscopy * AOP: Advanced oxidation

process * FWHM: Full width half maximum * ROS: Reactive oxygen species * VB: Valence band * CB: Conduction band REFERENCES * Rajagopalan, V. A new synergetic nanocomposite for dye

degradation in dark and light. _Sci. Rep._ 6(1), 1–10 (2016). Google Scholar * Isac, L., Cazan, C., Andronic, L. & Enesca, A. CuS-based nanostructures as catalysts for organic

pollutants photodegradation. _Catalysts._ 12(10), 1135 (2022). Article CAS Google Scholar * Koe, W. S., Lee, J. W. & Chong, W. C. An overview of photocatalytic degradation:

photocatalysts, mechanisms, and development of photocatalytic membrane. _Colloid Interface Sci. J._ 16(9), 3526 (2023). Google Scholar * Gupta, N. K. _et al._ Photocatalytic degradation of

organic pollutants over MFe2O4 (M = Co, Ni, Cu, Zn) nanoparticles at neutral PH. _Sci. Rep._ 10(1), 1–11 (2020). ADS MathSciNet Google Scholar * Tekin, D., Tekin, T. & Kiziltas, H.

Photocatalytic degradation kinetics of orange G dye over ZnO and Ag/ZnO thin film catalysts. _Sci. Rep._ 9(1), 1–7 (2019). Article CAS Google Scholar * Yu, Y. _et al._ Efficient

visible-light photocatalytic degradation system assisted by conventional Pd catalysis. _Sci. Rep._ 5, 1–7 (2015). Google Scholar * Trinh, D. T. T., Channei, D., Nakaruk, A. &

Khanitchaidecha, W. New insight into the photocatalytic degradation of organic pollutant over BiVO4/SiO2/GO nanocomposite. _Sci. Rep._ 11(1), 1–11 (2021). Article Google Scholar * Ouyang,

F. _et al._ Photocatalytic degradation of industrial acrylonitrile wastewater by F-S–Bi–TiO2 catalyst of ultrafine nanoparticles dispersed with SiO2 under natural sunlight. _Sci. Rep._

10(1), 1–10 (2020). Article Google Scholar * Etacheri, V., Di Valentin, C., Schneider, J., Bahnemann, D. & Pillai, S. C. Visible-light activation of TiO2 photocatalysts: Advances in

theory and experiments. _J. Photochem. Photobiol. C Photochem. Rev._ 25, 1–29 (2015). Article CAS Google Scholar * Gunture, Singh, A., Bhati, A., Khare, P., Tripathi, K. M. & Sonkar,

S. K. Soluble graphene nanosheets for the sunlight-induced photodegradation of the mixture of dyes and its environmental assessment. _Sci. Rep._ 9(1), 1–12 (2019). * Behnajady, M. A.,

Modirshahla, N., Shokri, M. & Vahid, B. Effect of operational parameters on degradation of malachite green by ultrasonic irradiation. _Ultrason. Sonochem._ 15(6), 1009–1014 (2008).

Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar * Han, F., Kambala, V. S. R., Srinivasan, M., Rajarathnam, D. & Naidu, R. Tailored titanium dioxide photocatalysts for the degradation of organic

dyes in wastewater treatment: A review. _Appl. Catal. A Gen._ 359(1–2), 25–40 (2009). Article CAS Google Scholar * Deng, Y. & Zhao, R. Advanced oxidation processes (AOPs) in

wastewater treatment. _Curr. Pollut. Rep._ 1(3), 167–176 (2015). Article CAS Google Scholar * Al-Nuaim, M. A., Alwasiti, A. A. & Shnain, Z. Y. The photocatalytic process in the

treatment of polluted water. _Chem. Pap._ 77(2), 677–701 (2023). Article CAS Google Scholar * Singh, N. P. _et al._ Effects of annealing temperature on structural and luminescence

properties of CdMoO4:Dy3+ phosphor synthesized at room temperature by co-precipitation method. _Solid State Sci._ 102(February), 106172 (2020). Article CAS Google Scholar * Ashwini, K.,

Pandurangappa, C., Avinash, K., Srinivasan, S. & Stefanakos, E. Synthesis, characterization and photoluminescence studies of samarium doped zinc sulfide nanophosphors. _J. Lumin._

221(February), 117097 (2020). Article CAS Google Scholar * Sooklal, K., Cullum, B. S., Angel, S. M. & Murphy, C. J. Photophysical properties of ZnS nanoclusters with spatially

localized Mn2+. _J. Phys. Chem. C._ 100(11), 4551–4555 (1996). Article CAS Google Scholar * Al-Jawad, S. M. H. & Ismail, M. M. Characterization of Mn, Cu, and (Mn, Cu) co-doped ZnS

nanoparticles. _J. Opt. Technol._ 84, 495–499 (2017). Article CAS Google Scholar * Pathak, C. S., Mishra, D. D., Agarwala, V. & Mandal, M. K. Optical properties of ZnS nanoparticles

produced by mechanochemical method. _Ceram. Int._ 38(8), 6191–6195 (2012). Article CAS Google Scholar * Jrad, A., Naouai, M., Abdallah, A., Ammar, S. & Turki-Kamoun, N. Doping ZnS

films with cobalt: Structural, compositional, morphological, optical, electrical, magnetic and photocatalytic properties. _Phys. B Condens. Matter_ 603(November 2020), 412776 (2021). Article

CAS Google Scholar * Ramu, S. & Vijayalakshmi, R. P. Effect of terbium doping on the structural and magnetic properties of ZnS nanoparticles. _Supercond. Nov. Magn._ 30(7), 1921–1925

(2017). Article CAS Google Scholar * Thakur, N., Thakur, N. & Kumar, K. Phytochemically and PVP stabilized TiO2 nanospheres for enhanced photocatalytic and antioxidant efficiency.

_Mater. Today Commun._ 35, 105587 (2023). Article CAS Google Scholar * Prabhu, R. R. & Abdul Khadar, M. Characterization of chemically synthesized CdS nanoparticles. _Pramana J.

Phys._ 65(5), 801–807 (2005). Article ADS CAS Google Scholar * Ajmal, A., Majeed, I., Malik, R. N., Idriss, H. & Nadeem, M. A Principles and mechanisms of photocatalytic dye

degradation on TiO2 based photocatalysts: A comparative overview. _RSC Adv._ 4(70), 37003–37026 (2014). Article ADS CAS Google Scholar * Hanifehpour, Y., Soltani, B., Amani-Ghadim, A.

R., Hedayati, B. & Khomami, B. Synthesis and characterization of samarium-doped ZnS nanoparticles: A novel visible light responsive photocatalyst. _Mater. Res. Bull._ 76, 411–421 (2016).

Article CAS Google Scholar * Faraz, M., Naqvi, F. K., Shakir, M. & Khare, N. Synthesis of samarium-doped zinc oxide nanoparticles with improved photocatalytic performance and

recyclability under visible light irradiation. _New J. Chem._ 42(3), 2295–2305 (2018). Article CAS Google Scholar * Poornaprakash, B. _et al._ Chromium doped ZnS nanoparticles: Chemical,

structural, luminescence and magnetic studies. _J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Electron._ 27(6), 6474–6479 (2016). Article CAS Google Scholar * Mercy, A., Anandhi, A. J., Murugesan, K. S.,

Jayavel, R. & Kanagadurai, R. Synthesis, structural and property studies of Ni doped cadmium sulphide quantum dots stabilized in DETA matrix. _J. Alloys Compd._ 593, 213–219 (2014).

Article CAS Google Scholar * Mercy, A., Sakthi Murugesan, K., Milton Boaz, B., Jesper Anandhi, A. & Kanagadurai, R. Synthesis and structural and optical characterization of Mn2+ doped

cadmium sulphide nanoparticles stabilized in DETA matrix. _J. Alloys Compd._ 554, 189–194 (2013). Article CAS Google Scholar * Thangeeswari, T., George, A. T. & Arun Kumar, A.

Optical properties and FTIR studies of cobalt doped ZnO nanoparticles by simple solution method. _Indian J. Sci. Technol._ 9(1), 4 (2016). Article Google Scholar * Yaemphutchong, S. _et

al._ Characterization, luminescence and dye adsorption study of manganese and samarium doped and co-doped zinc sulfide phosphors. _Opt. Mater. (Amst)._ 107(3), 109965 (2020). Article CAS

Google Scholar * Hanifehpour, Y. _et al._ Synthesis and characterization of samarium-doped ZnS nanoparticles: A novel visible light responsive photocatalyst. _Mater. Res. Bull._ 76, 411–421

(2016). Article CAS Google Scholar * Chang, S. S., Clair, B., Ruelle, J., Beauchene, J. & Di Renzo, F. Mesoporosity as a new parameter for understanding tension stress generation in

trees. _J. Exp. Bot._ 60(11), 3023–3030 (2009). Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar * Kannan, S., Subiramaniyam, N. P. & Sathishkumar, M. A novel green synthesis approach for improved

photocatalytic activity and antibacterial properties of zinc sulfide nanoparticles using plant extract of _Acalypha indica_ and _Tridax procumbens_. _J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Electron._ 31(12),

9846–9859 (2020). Article CAS Google Scholar * Seeta Rama Raju, G., Yu, J. S., Park, J. Y., Jung, H. C. & Moon, B. K. Photoluminescence and cathodoluminescence properties of

nanocrystalline Ca2Gd8Si6O26:Sm3+ phosphors. _J. Am. Ceram. Soc._ 95(1), 238–242 (2012). Article Google Scholar * Ratnam, B. V., Jayasimhadri, M. & Jang, K. Luminescent properties of

orange emissive Sm3+-activated thermally stable phosphate phosphor for optical devices. _Spectrochim. Acta Part A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc._ 132, 563–567 (2014). Article ADS CAS Google

Scholar * Yu, R. _et al._ Photoluminescence characteristics of Sm3+-doped Ba2CaWO6 as new orange-red emitting phosphors. _J. Lumin._ 152, 133–137 (2014). Article CAS Google Scholar *

Jamalaiah, B. C., Suresh Kumar, J., Mohan Babu, A., Suhasini, T. & Rama Moorthy, L. Photoluminescence properties of Sm3+ in LBTAF glasses. _J. Lumin._ 129(4), 363–369 (2009). Article

CAS Google Scholar * Blasse, G., Grabmaier, B. C., Blasse, G. & Grabmaier, B. C. _A General Introduction to Luminescent Materials_ 1–9 (Springer, 1994). Book Google Scholar * Singh,

N. P., Singh, N. R. & Singh, N. M. Optik Synthesis of CdMoO4: Sm3+ phosphors at room temperature and investigation on photoluminescence properties. _Opt. Int. J. Light Electron Opt._

156, 365–373 (2018). Article CAS Google Scholar * Singh, N. P., Singh, N. P., Singh, N. R. & Singh, N. M. Photoluminescence studies of CdWO4:Sm3+ phosphor: Concentration and annealing

effect. _Optik (Stuttg)._ 144, 490–497 (2017). Article ADS CAS Google Scholar * Naorem, R. S., Singh, N. P. & Singh, N. M. Photoluminescence properties of Tb3+ doped BiPO4

nanophosphor synthesised by co-precipitation method using ethylene glycol. _Mater. Technol._ 37(8), 610–617 (2022). Article ADS CAS Google Scholar * Premjit Singh, N., Rangeela Devi, Y.,

Rajmuhon Singh, N. & Mohondas Singh, N. Synthesis of Tb3+ ion doped ZnWO4 phosphors and investigation of their photoluminescence properties: Concentration effect. _Bull. Mater. Sci._

42(3), 17–20 (2019). Google Scholar * Jubeer, E. M. _et al._ Defect engineering for enhanced optical and photocatalytic properties of ZnS nanoparticles synthesized by hydrothermal method.

_Sci. Rep._ 13(1), 16820 (2023). Article ADS PubMed PubMed Central CAS Google Scholar * Ajibade, P. A., Solomane, N. & Sikakane, B. M. Morphological studies and photocatalytic

degradation of methylene blue by zinc sulfide nanoparticles. _Chalcogenide Lett._ 19(6), 429–438 (2022). Article CAS Google Scholar * Aziz, A. _et al._ Chitosan-zinc sulfide

nanoparticles, characterization and their photocatalytic degradation efficiency for azo dyes. _Int. J. Biol. Macromol._ 153, 502–512 (2020). Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar * Ajibade,

P. A. & Oluwalana, A. E. Photocatalytic degradation of single and binary mixture of brilliant green and rhodamine B dyes by zinc sulfide quantum dots. _Molecules_ 26(24), 7686 (2021).

Article PubMed PubMed Central CAS Google Scholar * Sathishkumar, M., Rajamanickam, A. T. & Saroja, M. Characterization, antimicrobial activity and photocatalytic degradation

properties of pure and biosynthesized zinc sulfide nanoparticles using plant extracts. _J. Mater. Sci._ 29(16), 14200–14209 (2018). CAS Google Scholar * Valizadeh, S., Rasoulifard, M. H.

& Dorraji, M. S. S. Adsorption and photocatalytic degradation of organic dyes onto crystalline and amorphous hydroxyapatite: Optimization, kinetic and isotherm studies. _Korean J. Chem.

Eng._ 33(2), 481–489 (2016). Article CAS Google Scholar * Xu, W. _et al._ Superparamagnetic mesoporous ferrite nanocrystal clusters for efficient removal of arsenite from water.

_CrystEngComm._ 15(39), 7895–7903 (2013). Article CAS Google Scholar * Chakrabarti, S. & Dutta, B. K. Photocatalytic degradation of model textile dyes in wastewater using ZnO as

semiconductor catalyst. _J. Hazard. Mater._ 112(3), 269–278 (2004). Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar * Chiou, M. S., Ho, P. Y. & Li, H. Y. Adsorption of anionic dyes in acid

solutions using chemically cross-linked chitosan beads. _Dye. Pigment._ 60(1), 69–84 (2004). Article CAS Google Scholar * Salama, A., Mohamed, A., Aboamera, N. M., Osman, T. A. &

Khattab, A. Photocatalytic degradation of organic dyes using composite nanofibers under UV irradiation. _Appl. Nanosci._ 8(1–2), 155–161 (2018). Article ADS CAS Google Scholar *

Gutierrez-Segura, E., Solache-Rios, M. & Colín-Cruz, A. Sorption of indigo carmine by a Fe-zeolitic tuff and carbonaceous material from pyrolyzed sewage sludge. _J. Hazard. Mater._

170(2–3), 1227–1235 (2009). Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar Download references AUTHOR INFORMATION Author notes * These authors contributed equally: Lal Lianmawii and N. Mohondas

Singh. AUTHORS AND AFFILIATIONS * Department of Chemistry, Mizoram University, Tanhril, Aizawl, Mizoram, 796004, India Lal Lianmawii & N. Mohondas Singh Authors * Lal Lianmawii View

author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * N. Mohondas Singh View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar

CONTRIBUTIONS L.L. and N.M.S. contributed equally to this work. All authors reviewed the manuscript. CORRESPONDING AUTHOR Correspondence to N. Mohondas Singh. ETHICS DECLARATIONS COMPETING

INTERESTS The authors declare no competing interests. ADDITIONAL INFORMATION PUBLISHER'S NOTE Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and

institutional affiliations. RIGHTS AND PERMISSIONS OPEN ACCESS This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing,

adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons

licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise

in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the

permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. Reprints and

permissions ABOUT THIS ARTICLE CITE THIS ARTICLE Lianmawii, L., Singh, N.M. Luminescence and photocatalytic degradation of indigo carmine in the presence of Sm3+doped ZnS nanoparticles. _Sci

Rep_ 13, 22450 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-49912-6 Download citation * Received: 14 July 2023 * Accepted: 13 December 2023 * Published: 17 December 2023 * DOI:

https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-49912-6 SHARE THIS ARTICLE Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content: Get shareable link Sorry, a shareable link is not

currently available for this article. Copy to clipboard Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative