The screenivf hungarian version is a valid and reliable measure accurately predicting possible depression in female infertility patients

- Select a language for the TTS:

- UK English Female

- UK English Male

- US English Female

- US English Male

- Australian Female

- Australian Male

- Language selected: (auto detect) - EN

Play all audios:

ABSTRACT Infertility patients, often in high distress, are entitled to being informed about their mental status compared to normative data. The objective of this study was to revalidate and

test the accuracy of the SCREENIVF, a self-reported tool for screening psychological maladjustment in the assisted reproduction context. A cross-sectional, questionnaire-based online survey

was carried out between December 2019 and February 2023 in a consecutive sample of female patients (N = 645, response rate 22.9%) in a university-based assisted reproduction center in

Hungary. Confirmatory factor analysis and cluster and ROC analyses were applied to test validity, sensitivity and specificity in relation to Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) scores. Model fit

was optimal (chi-square = 630.866, p < 0.001; comparative fit index = 0.99; root-mean-square error of approximation = 0.018 (90% CI 0.013–0.023); standardized-root-mean-square-residual =

0.044), and all dimensions were reliable (α > 0.80). A specific combination of cutoffs correctly predicted 87.4% of BDI-scores possibly indicative of moderate-to-severe depression (χ2(1)

= 220.608, p < 0.001, Nagelkerke R2 = 0.462, J = 66.4). The Hungarian version of the SCREENIVF is a valid and reliable tool, with high accuracy in predicting BDI-scores. Low response

rate may affect generalizability. The same instrument with different cutoffs can serve various clinical goals. SIMILAR CONTENT BEING VIEWED BY OTHERS INVESTIGATING THE ASSOCIATION BETWEEN

INFERTILITY AND PSYCHOLOGICAL DISTRESS USING AUSTRALIAN LONGITUDINAL STUDY ON WOMEN'S HEALTH (ALSWH) Article Open access 25 June 2022 PSYCHOMETRIC EVALUATION OF THE DEPRESSION ANXIETY

STRESS SCALE 8 AMONG WOMEN WITH CHRONIC NON-CANCER PELVIC PAIN Article Open access 30 November 2022 DESIGN AND PSYCHOMETRIC EVALUATION OF THE COLLABORATIVE COPING WITH INFERTILITY

QUESTIONNAIRE IN CANDIDATE OF ASSISTED REPRODUCTIVE TECHNIQUES Article Open access 11 May 2024 INTRODUCTION Infertility is a chronic disease commonly accompanied by psychological

symptomatology1. The rate of infertile women who meet the criteria for a psychiatric diagnosis may reach 40%2, with depressive3,4 and anxiety disorders5 being the most prevalent within

clinical samples. Women are almost unanimously found to present higher levels of mental health problems connected to infertility than men6. If distress reaches mental disorder levels, it

also seems to hinder the success of assisted reproduction techniques (ART)7. Psychosocial interventions increase psychological well-being and the likelihood of pregnancy in infertility

patients8,9,10,11. However, there is a large disparity between the number of patients reporting infertility distress and the number of those seeking psychological support12. Furthermore,

patients’ mental health status deteriorates with unsuccessful attempts. Therefore, it is necessary that patients (1) be informed about their mental status compared to normative data and (2)

should be checked at various time points during infertility treatment with properly validated mental health instruments. Several psychometric tools exist to assess adjustment to infertility,

the methodological trend moving from the use of generic tools, also applicable to infertile patients, to instruments developed specifically for this population. The European Society of

Human Reproduction and Embryology guideline13 lists 12 such tools, 5 generic and 7 specific. Out of the ones assessing mental health and not, say, perceived quality of care, experience of

patient-centeredness, or fertility status awareness, the most comprehensive and widely used instrument is the FertiQoL14,15, assessing patient needs in three domains: behavioral, emotional,

and social-relational. The one recommended for screening purposes is the SCREENIVF16, a combination of both generic and specific items, also assessing three domains (emotional,

social-relational and cognitive), and quick to complete. Out of the existing fertility-related questionnaires, only the FertiQoL and the SCREENIVF have been validated in Hungarian17,18. The

SCREENIVF consists of five subscales measuring anxiety, depression, social support, cognitions of helplessness and lack of infertility acceptance, each based on a reflective model, that is,

one in which all items are a manifestation of the same underlying construct19. The tool has been validated in Portuguese20, Dutch21, and Turkish22. Cutoff values are not uniform in these

studies, and there are considerable deviations in the rates of patients found to be at risk. A Hungarian validation study was performed on a small sample (N = 60), showing good reliability

and model fit but low specificity18. Therefore, further validation of the Hungarian version seems justified. The aim of the present study was to reinvestigate the psychometric

characteristics and screening capacities of the Hungarian SCREENIVF on a larger sample of Hungarian women in assisted reproduction. We hypothesized that (1) the psychometric properties of

the SCREENIVF can remain convincing and (2) the SCREENIVF is able to screen out ART patients to be further explored for mood disturbances if cutoffs for the Depression subscale and the

SCREENIVF Risk Factor scale are tested against real data and applied accordingly. RESULTS Study participants were in their mid-30s (Table 1), almost all in legally sanctioned heterosexual

relationships, qualified, employed and financially secure. The mean duration of, mainly primary, infertility was 3.3 years. Etiology was varied, with one-third unexplained or (yet) unknown.

The existence of other chronic diseases was not typical, but being overweight was rather frequent. RELIABILITY AND VALIDITY Reliability tests resulted in good to excellent Cronbach’s alpha

values (Table 2). All item-subscale correlations were higher than 0.40, indicating that the items contribute sufficiently to their subscales, except for one depression item, referring to

suicidal ideation (item 7, 0.381; Supplementary Table S1). Substantial correlations were found between the SCREENIVF subscales (Table 3), with the highest between Depression and Anxiety, and

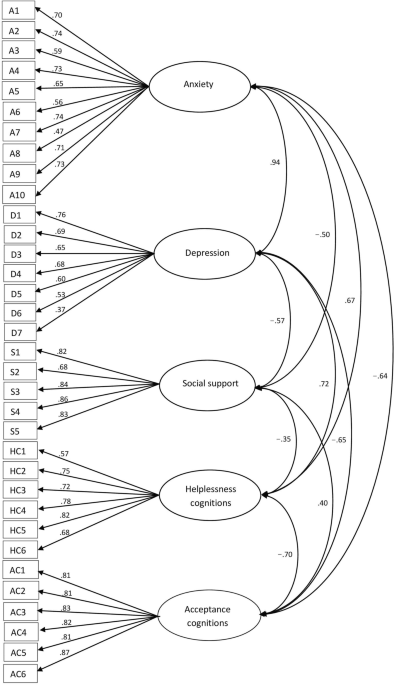

the lowest between Helplessness and Social Support. CFA with DWLS indicated optimal model fit (χ2 = 630.866, p < 0.001, RMSEA = 0.018 [CI90 = 0.013–0.023], CFI = 0.998, TLI = 0.997, SRMR

= 0.042). Standardized factor loadings ranged from 0.4 to 0.9, confirm to the majority of empirical research studies23, except for, again, the Depression item on suicidal ideation, which

had a weak factor loading (0.37; Fig. 1). CFA without the suicide-related Depression item, however, showed worse model fit than with it (χ2 = 615.692, p < 0.001, RMSEA = 0.020 [CI90 =

0.015–0.025], CFI = 0.997, TLI = 0.997, SRMR = 0.043). As hypothesized, all correlations between SCREENIVF subscales and cognate measures were significant, and most of them were fairly

strong (Table 3), the highest when the subscale and the external tool measured the same construct, e.g. Depression and the BDI, Anxiety and the STAI-S, Social Support and the MSPSS. The

Helplessness subscale related best to the Core FertiQoL, and the Acceptance subscale with FertiQol Emotional. The SCREENIVF Risk Factors total score showed the strongest relationship with

the Core FertiQoL, but was also related well to the BDI. CUTOFFS, SENSITIVITY AND SPECIFICITY Based on BDI results, 50.1% (N = 323) of our population was unaffected by depressive symptoms,

30.4% (N = 196) displayed mild symptoms, and 19.5% (N = 126) displayed moderate to severe, that is, clinically relevant symptomatology. The various cutoff values and corresponding ‘at risk’

sample rates in the original study, the five validation studies and the present study are listed in Table 4. All overall models of SCREENIVF risk categories (‘at risk’ vs ‘not at risk’) as

predictors of BDI categories (‘case’ vs ‘no-case’ and ‘no-to-mild’ vs ‘moderate-to-severe depression’) were statistically significant when compared to the null model, irrespective of

Depression subscale cutoff point. The best equation results were found in two cases: first, when a 3/4 cutoff on the SCREENIVF Depression subscale and a 0/1 cutoff on the SCREENIVF Risk

Factor scale were applied, a procedure correctly predicting 84.5% of BDI depression cases vs no-cases (χ2(1) = 220.246, p < 0.001, Nagelkerke R2 = 0.386, Youden index corresponding to the

cutoff: J = 69.0). Second, when a 6/7 cutoff on the SCREENIVF Depression subscale and a 1/2 cutoff on the SCREENIVF Risk Factors scale were applied, a procedure correctly predicting 87.4%

of BDI moderate-to-severe vs no-to-mild depression cases (χ2(1) = 220.608, p < 0.001, Nagelkerke R2 = 0.462, Youden index corresponding to the cutoff: J = 66.4; Supplementary Table S2).

Two-step cluster analysis of the SCREENIVF Risk Factors scale confirmed a natural demarcation between scores 1 and 2 (Supplementary Fig. S1). ROC analysis showed the best result when the

SCREENIVF Risk Factors scale was used with a 4/5 cutoff on the Depression subscale, with BDI no-to-mild vs moderate-to-severe depression applied as a state variable (AUC = 0.918, CI [0.895,

0.940]). ROC curves indicated that the SCREENIVF had a better diagnostic value when used to discriminate between no-to-mild and moderate-to-severe BDI cases of depression (AUCs between 0.647

and 0.898) than when distinguishing cases from no-cases (AUCs between 0.603 and 0.795). When ROC curves for all individual and total SCREENIVF risk factors were compared, the AUC for the

total factor (0.898) was superior to that of all subfactors, including Depression (0.848; Supplementary Fig. S2). DISCUSSION The aim of this study was to revalidate the Hungarian version of

the SCREENIVF on a fairly large sample and to test its ability to grasp emotional maladjustment with various cutoffs on the Depression subscale and the total Risk Factors scale. The

SCREENIVF proved to be a valid and reliable instrument to detect emotional maladjustment among Hungarian women undergoing ART, and was able to discriminate between scores possibly indicative

of different levels of depression as measured by the BDI. Our respondents were typical of ART patients in terms of help-seeking age (mid-30s) in developed countries25, where the age of

family formation is constantly increasing26. Additionally, our sample displayed fairly high socioeconomic status, a common finding among patients in ART27. The homogeneity of our sample’s

marital status reflects Hungarian legislation, namely, that ART is allowed only for married or officially cohabitating opposite-sex couples and single women who cannot have children

otherwise. The unfortunate coincidence of the study timelines with the COVID-19 pandemic posed considerable challenges. Participant enrolment practically stopped during the first wave, when

only life-saving operations were permitted. As an exception, however, immediately after the first wave, the Hungarian health regulations allowed for assisted reproductive interventions to be

performed. Even so, with the threat of treatment cancellations due to patients’ virus infection, partners not being allowed to accompany women to examinations and interventions, and the

general existential and financial concerns, COVID-19 most probably influenced the stress of infertility28. Unfortunately, our original, preregistered study protocol did not allow us to

investigate the added effect of the pandemic on the mental wellbeing of the participants. Online data collection may have introduced sampling bias due to low response rate, possibly caused

by overlooking the announcement, interpreting it as junk mail, or completion interrupted by technical or personal difficulties29. Our response rate (22.9%) was lower than average proportions

found in meta-analyses (34–36%)30,31. This was not attributable to a lack of internet access, since we were able, with permission, to extract from the medical database email addresses for

all patients, who thus had equal opportunities to fill in the questionnaire, with illegitimate participation also minimized. Low response rates do not necessarily indicate large nonresponse

error, i.e. that nonrespondents would have provided different answers than actual respondents32. All of our Cronbach’s alpha values fall within the intervals found in previous studies. The

Depression subscale also fits in the tendency of being the least consistent, with the suicidality item not contributing well to its reliability. Even so, the subscale proved more reliable

than in Irmak Vural and colleagues’ study22, where four items had to be left out. Despite the poor factor loading of the suicidality item, we do not recommend its removal, since (1) model

fit indices did not improve with its removal, and (2) the item may warn of suicide risk, signaling an urgent need for further exploration. This is of utmost importance in Hungary, which is

customarily among the first five highest suicide-rate states in Europe, e.g. second highest in 2020 (https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/products-eurostat-news/w/edn-20230908-3). Although two

of the previous validation studies of the SCREENIVF20,21 used parcel- rather than item-based CFA, here, DWLS estimation yielded excellent results. DWLS is specifically designed for

categorical (e.g., binary or ordinal) data in which neither the normality assumption nor the continuity property is plausible23, especially for higher sample sizes33. Therefore, the

hypothesis of the five latent variables underlying the SCREENIVF seems to be confirmed. Previous literature on the SCREENIVF draws attention to probable transcultural differences in

cutoffs20 and to a need for ROC analyses in establishing them21. We decided to test cutoff points in relation to a ‘gold standard’ measure, the BDI, because depression tools are commonly

used as criterion measures of psychological maladjustment in infertility34. We found that the SCREENIVF is able to detect possible depression, reaching the best sensitivity with a 3/4 cutoff

on the Depression subscale and 0/1 on the Risk Factors scale. Additionally, it is able to identify presumable moderate-to-severe cases of depression, showing the best specificity with a 6/7

cutoff on the Depression subscale and 1/2 on the Risk Factors scale. When the goal is a good trade-off between sensitivity and specificity, the SCREENIVF Risk Factors scale is best used

with a 4/5 cutoff on the Depression subscale, to separate no-to-mild cases from those to be further evaluated for moderate-to-severe depression. Therefore, if one wants to use the SCREENIVF

to identify the highest number of possible cases of psychological disorders, a lower cutoff value is needed to maximize sensitivity. If, however, the SCREENIVF is intended to find

individuals most likely already affected by depression, a higher cutoff value is needed to maximize specificity. Our analysis showed that the SCREENIVF serves both goals fairly well as a

stand-alone tool able to signal different levels of emotional maladjustment, depending on the purposes of the clinician. Ockhuijsen et al.21 found that the SCREENIVF did not do well at

prognosticating whether ‘at risk’ patients would actually develop psychological problems during treatment. We found that the SCREENIVF has high screening accuracy at the time of

administration. Thus, we believe that the SCREENIVF can safely be used for screening out ‘afflicted’ rather than ‘at-risk-for-later-maladjustment’ patients, who can then be referred to a

full diagnostic evaluation. Additionally, given that the ROC curve for the SCREENIVF Risk Factors total scale outperformed that of the Depression subscale, it seems that there is more to the

emotional disturbance in infertility than just depressed mood: anxiety, helplessness, lack of social support and unacceptance of infertility all add their own shades to the clinical aspect.

ROC analysis can be combined with utility-based decisions to determine optimal cutoff points35, in this case, a desirable balance between the number of patients found vulnerable and the

financial costs of delivering psychosocial support. In Hungary, where there is a scarcity of mental health professionals in state-subsidized facilities, it is essential that we single out

patients most in need of psychological services by applying higher thresholds on SCREENIVF scales. The proportion (22.8%) of the possibly afflicted population spotted in this sample is

realistic in terms of healthcare possibilities on the Eastern European scene, while also comparable to international prevalence data. A great strength of our study is the use of four cognate

measures, all validated in Hungarian, to test the convergent validity of the SCREENIVF, two of them measuring general psychological distress, and two assessing infertility-related issues.

Additionally, arbitrariness was ruled out by relying on statistical methods that reveal natural groupings in real-life data. We worked with a relatively sizable sample from a large fertility

center in the capital that also serves IVF patients from the rest of the country. The study has some limitations. Including only women made it impossible to validate the SCREENIVF in men or

at the couple level. The cross-sectional design did not allow for testing the predictive validity of the SCREENIVF. There was only one measurement point, so neither test–retest reliability

nor responsiveness was assessed. We did not collect data on ART treatment type, so we could not test either the tool’s discriminative validity or the possibly changing status of the patients

in different stages of ART. Form X of the STAI was used here, a version still predominantly administered in Hungary, a circumstance that, however, may make international comparisons

problematic. Online sampling resulted in a lower than average response rate, which may decrease generalizability. Finally, the overlap of our study timelines with the COVID-19 pandemic may

be a source of bias, since our design made it impossible to discern infertility stress per se from the distress caused by COVID-specific effects. Future studies are warranted to overcome the

above shortcomings. CONCLUSIONS Our findings demonstrated the SCREENIVF to be a valid and reliable measure with high accuracy in predicting possible depression, which gives it significant

clinical value in assessing the psychological status of Hungarian women pursuing ART. Given its fair screening precision and goal-adjusted flexibility, we highly recommend its administration

in routine fertility care to promote mental health and thus raise the probability of treatment adherence and success. METHODS STUDY PARTICIPANTS The study was nested in the recruitment and

eligibility phase of a randomized controlled trial on the effects of a psychosocial intervention on women’s well-being and ART outcomes (Clinical Trials.gov: NCT04151485). The study was

approved by the Semmelweis University Regional and Institutional Committee of Science and Research Ethics, Budapest (reference number: 83/2019) and was carried out in accordance with the

tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki. The research is reported in conformity with the COnsensus-based Standards for the selection of health status Measurement INstruments (COSMIN) reporting

guideline for studies on measurement properties of patient reported outcome measures36. The inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) female sex; (2) reproductive age (18 to 45 years); (3)

fluency in Hungarian; and (4) failure to achieve pregnancy after 12 or more months of regular unprotected sexual intercourse37. Women treated in the Assisted Reproduction Center of the

Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology of Semmelweis University, Budapest, between December 2019 and February 2023 (_n_ = 2830) were consecutively contacted via email directing patients to

a web survey. Sample size was determined so as to fall in between those in previous validation studies of the SCREENIVF38. Eleven addresses were erroneous; thus, 2819 emails were

successfully sent. Participation was voluntary and anonymous and based on informed consent after learning about the purpose and data management of the research. The overall response rate was

22.9%, resulting in a sample of _n_ = 647 responders. Questionnaires were completed online, designed in a way that missing data were not allowed. Two men were found to have provided data,

which were removed from analysis. The final sample consisted of _N_ = 645 participants (Fig. 2). MEASUREMENT INSTRUMENTS SCREENIVF The 34-item questionnaire16 consists of five subscales

measuring five risk factors: (1) _anxiety_ (10 items originating from the Spielberger State-Trait Anxiety Scale39); (2) _depression_ (a 7-item version of the Beck Depression Inventory for

screening among primary care patients24); (3) _perceived social support_ (5 items, derived from the Inventory of Social Involvement40); and infertility-related cognitions of (4)

_helplessness_ (6 items) and (5) _acceptance_ (6 items), all from the Illness Cognition Questionnaire for IVF patients41,42. Each subscale preserves the original question and response format

of its parent questionnaire. Cutoffs on the subscales differ from culture to culture. Dichotomous scores are given on each risk factor: 1 if the patient’s score falls in the critical range

on the respective subscale, and 0 if not. Adding up all subscale scores yields the final Risk Factors score ranging between 0 (no risk factor) and 5 (5 risk factors). Subjects are considered

to be at risk when scoring above 0. Cronbach’s alpha values in our sample ranged between 0.81 and 0.93. SPIELBERGER STATE-TRAIT ANXIETY INVENTORY (STAI) The Spielberger State-Trait Anxiety

Inventory39,43 assesses anxiety on two 20-item scales: the State Scale (STAI-S), measuring transient states of subjective fear, tension and vegetative excitement, and the Trait Scale

(STAI-T), capturing a more stable tendency of an individual to become anxious. All questions are answered on 4-point Likert scales. The results on both scales can range from 20 to 80, where

a higher score indicates greater levels of anxiety. Form X, freely available and most widely administered in research and practice in Hungary, was used in this study. Cronbach’s alpha values

in our sample were 0.95 and 0.92, respectively. BECK DEPRESSION INVENTORY (BDI) The Beck Depression Inventory44,45 contains 21 items with 4-point Likert scale responses about symptoms of

depression, such as pessimism, lack of satisfaction, and guilt. Results can range from 0 to 63. Conventional cutoff scores on the BDI yield the following categories: normal range (0–9

points), mild (10–19 points), moderate (20–29 points), and severe depression (30–63 points). The nonclinical/clinical cutoff of 18/19 routinely applied in Hungarian studies46 is almost

identical to the 19/20 cutoff suggested by Beck and associates44. In the present sample, the questionnaire yielded a Cronbach’s alpha score of 0.90. MULTIDIMENSIONAL SCALE OF PERCEIVED

SOCIAL SUPPORT (MSPSS) The Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support47,48 consists of 12 items across 3 subscales, assessing the individual’s subjective social support from family,

friends, and significant others on 8-point Likert scales. The higher the mean on a factor or altogether, the stronger the support perceived by the responder. Cronbach’s alpha value in our

sample was 0.87. FERTILITY QUALITY OF LIFE SCALE (FERTIQOL) The FertiQoL14,17 is a 36-item instrument for the assessment of the fertility-specific quality of life (QoL) of individuals. The

tool contains 2 general items, a core and an optional treatment section. Core FertiQoL is composed of four subscales: Emotional; Mind–body; Relational; and Social. Treatment FertiQoL

comprises two subscales: Environment and Treatment tolerability. Response formats follow 5-point Likert scales. All scale scores range between 0 and 100, with higher scores indicative of

better QoL. In the present study, only the Core FertiQoL was used. Internal reliability was 0.90 for the module and ranged between 0.75 and 0.86 for the subscales. Sociodemographic

information such as age, marital status, number of existing children, residence, education, employment status, personal perception of financial situation, and health information such as

height, weight, duration and etiology of infertility were gathered. TRANSLATION AND ADAPTATION After obtaining permission via email from the developer of the original questionnaire,

adaptation and translation were performed on version English 2.0 of the SCREENIVF following international recommendations49,50. Anxiety and depression subscale items were identified within

the extant valid translations of the STAI and the BDI. For the remaining three subscales, the following steps were taken: forward translation by two translators fluent in both languages;

consensus Hungarian version by a psychologist and a linguist; backward translation by two bilingual linguists; final version agreed upon by an expert committee of leading psychologists

proficient in English and familiar with the research topic; and finally, pilot testing for comprehensibility, face validity and cultural appropriateness with 20 ART patients. DESCRIPTIVE

STATISTICS Statistical analyses were performed with IBM SPSS for Windows, v20.051, and the lavaan R package52. All scale data were tested for normality of distribution with Shapiro‒Wilk

tests. RELIABILITY AND VALIDITY Internal consistency was measured with Cronbach’s alpha computed on the basis of the factor loadings of each item in a subscale. Reliability is acceptable

when Cronbach’s alpha is higher than.70, and values > 0.80 are commonly considered good53. To test concurrent validity, Spearman rank coefficients were computed to assess correlations

between SCREENIVF subscales (not normally distributed) and their corresponding criterion measures. To avoid overlap, items used in the SCREENIVF were removed from the BDI and the STAI, and

correlation tests were run with the bulk of remaining items only. As for construct validity, since the SCREENIVF is a compilation of preexisting, unidimensional scales, and its underlying

factor structure has already been identified in earlier studies, exploratory factor analysis is no longer necessary54. To verify the postulated underlying latent constructs in the Hungarian

version, confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was performed. Instead of the maximum likelihood (ML) method, which assumes that the observed indicators follow a continuous and multivariate

normal distribution, diagonally weighted least squares (DWLS) was used, a method suggested to be superior to ML when ordinal data are analyzed23. All five factors were allowed to correlate.

No cross-loadings or correlated errors were allowed. The goodness of fit of the model was evaluated by χ2 tests, the standardized root mean square residual (SRMR), root mean square error of

approximation (RMSEA), and the comparative fit index (CFI). A model is considered to show good fit with SRMR/RMSEA < 0.08, and CFI/TLI > 0.90/0.9555,56,57. CUTOFFS, SENSITIVITY AND

SPECIFICITY A review of cutoffs applied in the original16 and the validation studies of the SCREENIVF18,20,21,22 was performed to inform thresholds for use in the present study. First,

cutoff points for all Hungarian SCREENIVF subscales were calculated on the basis of sample means plus/minus standard deviations (M ± SD), as adequate. In the case of the Depression subscale,

two other cut-points were also tested: 3/4, suggested by the developers of the SCREENIVF following Beck and colleagues24, and 4/5, a demarcation point resulting from a two-step cluster

analysis that reveals natural groupings in a dataset. A similar cluster analysis was also performed on the SCREENIVF Risk Factors scale results. Sensitivity and specificity measurements were

performed for depression, the most commonly used indicator of psychological maladjustment in infertility, which, unlike anxiety, has internationally accepted scale cutoffs as reference

points. Sensitivity here refers to the ability of the SCREENIVF to correctly identify patients falling into the ‘clinically depressed’ category on the BDI, while specificity refers to its

ability to correctly identify patients without a mood disorder. Binary logistic regression was used to test the power of the SCREENIVF with different cut points to predict BDI depression

categories. Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves were calculated for all SCREENIVF subscales and the Risk Factors scale, with BDI scores serving as a reference. ROC curves are a

plot of false positives against true positives, where the closer the area under the curve (AUC) of a test is to 1.0, the better it is in terms of sensitivity and specificity58. AUC is

heuristically interpreted as small (0.5 < AUC ≤ 0.7), moderate (0.7 < AUC ≤ 0.9), or high (0.9 < AUC ≤ 1)59. Youden Indexes of different cut-points were computed60. For all

analyses, p < 0.05 was considered an indication of significance. DATA AVAILABILITY The data that support the findings of this study are available and can be requested by academic

researchers from the corresponding author. REFERENCES * World Health Organization. _Infertility_. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/infertility (2023). * Becker, M. A. _et

al._ Psychiatric aspects of infertility. _Am. J. Psychiatry_ 176, 765–766 (2019). Article PubMed Google Scholar * Kiani, Z., Simbar, M., Hajian, S. & Zayeri, F. The prevalence of

depression symptoms among infertile women: A systematic review and meta-analysis. _Fertil. Res. Pract._ 7, 6 (2021). Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Nik Hazlina, N. H.,

Norhayati, M. N., Shaiful Bahari, I. & Nik Muhammad Arif, N. A. Worldwide prevalence, risk factors and psychological impact of infertility among women: A systematic review and

meta-analysis. _BMJ Open_ 12, e057132 (2022). Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Kiani, Z. _et al._ The prevalence of anxiety symptoms in infertile women: A systematic review

and meta-analysis. _Fertil. Res. Pract._ 6, 7 (2020). Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Almutawa, Y. M., AlGhareeb, M., Daraj, L. R., Karaidi, N. & Jahrami, H. A

systematic review and meta-analysis of the psychiatric morbidities and quality of life differences between men and women in infertile couples. _Cureus._ (2023). * Purewal, S., Chapman, S. C.

E. & Van Den Akker, O. B. A. Depression and state anxiety scores during assisted reproductive treatment are associated with outcome: A meta-analysis. _Reprod. Biomed. Online_ 36,

646–657 (2018). Article PubMed Google Scholar * Katyal, N., Poulsen, C. M., Knudsen, U. B. & Frederiksen, Y. The association between psychosocial interventions and fertility treatment

outcome: A systematic review and meta-analysis. _Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol._ 259, 125–132 (2021). Article PubMed Google Scholar * Zhou, R., Cao, Y.-M., Liu, D. & Xiao,

J.-S. Pregnancy or psychological outcomes of psychotherapy interventions for infertility: A meta-analysis. _Front. Psychol._ 12, 643395 (2021). Article PubMed PubMed Central Google

Scholar * Ha, J.-Y., Park, H.-J. & Ban, S.-H. Efficacy of psychosocial interventions for pregnancy rates of infertile women undergoing in vitro fertilization: A systematic review and

meta-analysis. _J. Psychosom. Obstet. Gynecol._ 44, 2142777 (2023). Article Google Scholar * Dube, L., Bright, K., Hayden, K. A. & Gordon, J. L. Efficacy of psychological interventions

for mental health and pregnancy rates among individuals with infertility: A systematic review and meta-analysis. _Hum. Reprod. Update_ 29, 71–94 (2023). Article PubMed Google Scholar *

Boivin, J. _et al._ Tailored support may reduce mental and relational impact of infertility on infertile patients and partners. _Reprod. Biomed. Online_ 44, 1045–1054 (2022). Article PubMed

Google Scholar * Gameiro, S. _et al._ ESHRE guideline: Routine psychosocial care in infertility and medically assisted reproduction—A guide for fertility staff. _Hum. Reprod._ 30,

2476–2485 (2015). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Boivin, J., Takefman, J. & Braverman, A. The fertility quality of life (FertiQoL) tool: Development and general psychometric

properties. _Fertil. Steril._ 96, 409–415 (2011). Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Woods, B. M. _et al._ A review of the psychometric properties and implications for the

use of the fertility quality of life tool. _Health Qual. Life Outcomes_ 21, 45 (2023). Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Verhaak, C. M., Lintsen, A. M. E., Evers, A. W. M.

& Braat, D. D. M. Who is at risk of emotional problems and how do you know? Screening of women going for IVF treatment. _Hum. Reprod._ 25, 1234–1240 (2010). Article CAS PubMed Google

Scholar * Szigeti F., J. _et al._ Quality of life and related constructs in a group of infertile Hungarian women: A validation study of the FertiQoL. _Hum. Fertil._ 25, 456–469 (2022).

Article Google Scholar * Prémusz, V. _et al._ Introducing the Hungarian version of the SCREENIVF tool into the clinical routine screening of emotional maladjustment. _Int. J. Environ. Res.

Public. Health_ 19, 10147 (2022). Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Fayers, P. M., Hand, D. J., Bjordal, K. & Groenvold, M. Causal indicators in quality of life

research. _Qual. Life Res._ 6, 393–406 (1997). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Lopes, V., Canavarro, M. C., Verhaak, C. M., Boivin, J. & Gameiro, S. Are patients at risk for

psychological maladjustment during fertility treatment less willing to comply with treatment? Results from the Portuguese validation of the SCREENIVF. _Hum. Reprod._ 29, 293–302 (2014).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Ockhuijsen, H. D. L., Van Smeden, M., Van Den Hoogen, A. & Boivin, J. Validation study of the SCREENIVF: An instrument to screen women or men on

risk for emotional maladjustment before the start of a fertility treatment. _Fertil. Steril._ 107, 1370–1379 (2017). Article PubMed Google Scholar * Irmak Vural, P., Körpe, G. &

Aslan, E. Validity and reliability of the Turkish version of screening tool on distress in fertility treatment (SCREENIVF). _Psychiatr. Danub._ 33, 278–287 (2021). PubMed Google Scholar *

Li, C.-H. Confirmatory factor analysis with ordinal data: Comparing robust maximum likelihood and diagonally weighted least squares. _Behav. Res. Methods_ 48, 936–949 (2016). Article ADS

PubMed Google Scholar * Beck, A. T., Guth, D., Steer, R. A. & Ball, R. Screening for major depression disorders in medical inpatients with the beck depression inventory for primary

care. _Behav. Res. Ther._ 35, 785–791 (1997). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Chandra, A., Copen, C. E. & Stephen, E. H. Infertility service use in the United States: Data from

the National Survey of Family Growth, 1982–2010. _Natl. Health Stat. Rep._ 1, 1–21 (2014). Google Scholar * Passet-Wittig, J. & Greil, A. L. On estimating the prevalence of use of

medically assisted reproduction in developed countries: A critical review of recent literature. _Hum. Reprod. Open_ 2021, 065 (2021). Article Google Scholar * Datta, J. _et al._ Prevalence

of infertility and help seeking among 15,000 women and men. _Hum. Reprod. Oxf. Engl._ 31, 2108–2118 (2016). Article CAS Google Scholar * Irani, M., Bashtian, M. H., Soltani, N. &

Khabiri, F. Impact of COVID-19 on mental health of infertile couple: A rapid systematic review. _J. Educ. Health Promot._ 11, 404 (2022). Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar *

Lefever, S., Dal, M. & Matthíasdóttir, Á. Online data collection in academic research: Advantages and limitations. _Br. J. Educ. Technol._ 38, 574–582 (2007). Article Google Scholar *

Daikeler, J., Silber, H. & Bošnjak, M. A meta-analysis of how country-level factors affect web survey response rates. _Int. J. Mark. Res._ 64, 306–333 (2022). Article Google Scholar *

Shih, T.-H. & Fan, X. Comparing response rates from web and mail surveys: A meta-analysis. _Field Methods_ 20, 249–271 (2008). Article Google Scholar * Groves, R. M. & Peytcheva,

E. The impact of nonresponse rates on nonresponse bias: A meta-analysis. _Public Opin. Q._ 72, 167–189 (2008). Article Google Scholar * Koğar, H. & Yilmaz Koğar, E. Comparison of

different estimation methods for categorical and ordinal data in confirmatory factor analysis. _Eğitimde Ve Psikolojide Ölçme Ve Değerlendirme Derg._ 6, 1 (2015). Google Scholar * Tavousi,

S. A., Behjati, M., Milajerdi, A. & Mohammadi, A. H. Psychological assessment in infertility: A systematic review and meta-analysis. _Front. Psychol._ 13, 961722 (2022). Article PubMed

PubMed Central Google Scholar * Hajian-Tilaki, K. Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis for medical diagnostic test evaluation. _Casp. J. Intern. Med._ 4, 627–635

(2013). Google Scholar * Gagnier, J. J., Lai, J., Mokkink, L. B. & Terwee, C. B. COSMIN reporting guideline for studies on measurement properties of patient-reported outcome measures.

_Qual. Life Res._ 30, 2197–2218 (2021). Article PubMed Google Scholar * Zegers-Hochschild, F. _et al._ The international glossary on infertility and fertility care, 2017. _Fertil.

Steril._ 108, 393–406 (2017). Article PubMed Google Scholar * Bacchetti, P. Current sample size conventions: Flaws, harms, and alternatives. _BMC Med._ 8, 17 (2010). Article PubMed

PubMed Central Google Scholar * Spielberger, C. D., Gorsuch, R. L. & Lushene, R. E. _Manual for the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory_ (Consulting Psychologists Press, 1970). Google

Scholar * van Dam-Baggen, R. & De Kraaimaat, F. W. Inventarisatielijst Sociale Betrokkenheid (ISB): een zelfbeoordelingslijst om sociale steun te meten (The inventory for social support

(ISB): A self-report inventory for the measurement of social support). _Gedragstherapie_ 25, 26–46 (1992). Google Scholar * Evers, A. W. _et al._ Beyond unfavorable thinking: The illness

cognition questionnaire for chronic diseases. _J. Consult. Clin. Psychol._ 69, 1026–1036 (2001). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Verhaak, C. M., Smeenk, J. M. J., Van Minnen, A.,

Kremer, J. A. M. & Kraaimaat, F. W. A longitudinal, prospective study on emotional adjustment before, during and after consecutive fertility treatment cycles. _Hum. Reprod._ 20,

2253–2260 (2005). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Sipos, K. & Sipos, M. In _The Development and Validation of the Hungarian Form of the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory_ Vol. 2 (eds

Spielberger, C. D. & Dia-Guerrero, R.) 27–39 (Hemisphere Publishing Corporation, 1983). Google Scholar * Beck, A. T. An inventory for measuring depression. _Arch. Gen. Psychiatry_ 4,

561 (1961). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Kopp, M., Skrabski, Á. & Czakó, L. Összehasonlító mentálhigiénés vizsgálatokhoz ajánlott módszertan. _Végeken_ 1, 4–24 (1990). Google

Scholar * Kopp, M. & Skrabski, Á. _Magyar Lelkiállapot_ (Végeken Alapítvány, 1992). Google Scholar * Zimet, G. D., Dahlem, N. W., Zimet, S. G. & Farley, G. K. The Multidimensional

Scale of Perceived Social Support. _J. Pers. Assess._ 52, 30–41 (1988). Article Google Scholar * Papp-Zipernovszky, O., Kékesi, M. Z. & Jámbori, S. A Multidimenzionális Észlelt Társas

Támogatás Kérdőív magyar nyelvű validálása. _Mentálhig. És Pszichoszomatika_ 18, 230–262 (2017). Article Google Scholar * Gudmundsson, E. Guidelines for translating and adapting

psychological instruments. _Nord. Psychol._ 61, 29–45 (2009). Article Google Scholar * Tsang, S., Royse, C. F. & Terkawi, A. S. Guidelines for developing, translating, and validating a

questionnaire in perioperative and pain medicine. _Saudi J. Anaesth._ 11, S80–S89 (2017). Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Corp, I. B. M. _IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows,

Version 20.0_ (IBM Corp, 2011). Google Scholar * Rosseel, Y. lavaan : An R package for structural equation modeling. _J. Stat. Softw._ 48, 2 (2012). Article Google Scholar * Henson, R.

K. Understanding internal consistency reliability estimates: A conceptual primer on coefficient alpha. _Meas. Eval. Couns. Dev._ 34, 177–189 (2001). Article Google Scholar * Stevens, J. P.

_Applied Multivariate Statistics for the Social Sciences_ (Routledge, 2009). Google Scholar * Bentler, P. M. & Bonett, D. G. Significance tests and goodness of fit in the analysis of

covariance structures. _Psychol. Bull._ 88, 588–606 (1980). Article Google Scholar * Browne, M. W. & Cudeck, R. Alternative ways of assessing model fit. _Sociol. Methods Res._ 21,

230–258 (1992). Article Google Scholar * Hu, L. & Bentler, P. M. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives.

_Struct. Equ. Model. Multidiscip. J._ 6, 1–55 (1999). Article Google Scholar * Lalkhen, A. G. & McCluskey, A. Clinical tests: Sensitivity and specificity. _Contin. Educ. Anaesth. Crit.

Care Pain_ 8, 221–223 (2008). Article Google Scholar * Swets, J. A. Measuring the accuracy of diagnostic systems. _Science_ 240, 1285–1293 (1988). Article ADS MathSciNet CAS PubMed

Google Scholar * Youden, W. J. Index for rating diagnostic tests. _Cancer_ 3, 32–35 (1950). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar Download references ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The authors thank all

participants for providing data for the study. FUNDING Open access funding provided by Semmelweis University. AUTHOR INFORMATION AUTHORS AND AFFILIATIONS * Institute of Behavioral Sciences,

Semmelweis University, Üllői út 26, 1085, Budapest, Hungary Judit Szigeti F., Péter Przemyslaw Ujma & György Purebl * Department of Otorhinolaryngology, Head and Neck Surgery, Semmelweis

University, Üllői út 26, 1085, Budapest, Hungary Judit Szigeti F. * Department of Psychology, University of Graz, Dachgeschoß – 2, Stock, 2, 8010, Graz, Austria Réka E. Sexty * Doctoral

School of Mental Health Sciences, Semmelweis University, Üllői út 26, 1085, Budapest, Hungary Georgina Szabó * Department of Psychiatry, North Buda Saint John’s Hospital Center and

Outpatient Clinic, Diós Árok 1-3, 1125, Budapest, Hungary Georgina Szabó * Department of Clinical Psychology, Semmelweis University, Budapest, Hungary Csaba Kazinczi * Doctoral School of

Clinical Medicine, University of Szeged, 6722, Szeged, Hungary Csaba Kazinczi * Directorate for Human Reproduction, National Directorate General for Hospitals, Buda-part tér 2, BudaPart Gate

Irodaház A. ép. 406, 1117, Budapest, Hungary Zsuzsanna Kéki * Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Assisted Reproduction Center, Semmelweis University, Üllői út 26, 1085, Budapest,

Hungary Miklós Sipos Authors * Judit Szigeti F. View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Réka E. Sexty View author publications You can also

search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Georgina Szabó View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Csaba Kazinczi View author publications

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Zsuzsanna Kéki View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Miklós Sipos View author

publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Péter Przemyslaw Ujma View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * György

Purebl View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar CONTRIBUTIONS J.Sz.F., Gy.P., P.P.U. conceptualized the study and its methodology. J.Sz.F. and

M.S. collected the data. J.Sz.F., R.S., G.Sz., Cs.K., Zs. K., P.P.U. did the formal analysis and interpreted the results. J.Sz.F. wrote the original draft. J.Sz.F., R.S., G.Sz., Cs.K., Zs.

K., M.S., P.P.U., and Gy.P reviewed and edited the paper. All authors approved the final version of this manuscript. CORRESPONDING AUTHOR Correspondence to Judit Szigeti F.. ETHICS

DECLARATIONS COMPETING INTERESTS The authors declare no competing interests. ADDITIONAL INFORMATION PUBLISHER'S NOTE Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims

in published maps and institutional affiliations. SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION. RIGHTS AND PERMISSIONS OPEN ACCESS This article is licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original

author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the

article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your

intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence,

visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. Reprints and permissions ABOUT THIS ARTICLE CITE THIS ARTICLE Szigeti F., J., Sexty, R.E., Szabó, G. _et al._ The SCREENIVF Hungarian

version is a valid and reliable measure accurately predicting possible depression in female infertility patients. _Sci Rep_ 14, 12880 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-63673-w

Download citation * Received: 19 November 2023 * Accepted: 31 May 2024 * Published: 05 June 2024 * DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-63673-w SHARE THIS ARTICLE Anyone you share the

following link with will be able to read this content: Get shareable link Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article. Copy to clipboard Provided by the Springer

Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative