Associations of physical activity in rural life with happiness and ikigai: a cross-sectional study

- Select a language for the TTS:

- UK English Female

- UK English Male

- US English Female

- US English Male

- Australian Female

- Australian Male

- Language selected: (auto detect) - EN

Play all audios:

ABSTRACT Physical activity is associated with subjective well-being. In rural communities, however, physical activity may be affected by environmental factors (e.g., nature and

socioecological factors). We examined the association of two physical activities in rural life (farming activity and snow removal) with subjective well-being in terms of happiness and

_ikigai_ (a Japanese word meaning purpose in life). In this cross-sectional study, we analysed data collected from community-dwelling adults aged ≥ 40 years in the 2012–2014 survey of the

Uonuma cohort study, Niigata, Japan. Happiness (_n_ = 31,848) and _ikigai_ (_n_ = 31,785) were evaluated with respect to farming activity from May through November and snow removal from

December through April by using an ordinal logistic regression model with adjustments for potential confounders. The analyses were conducted in 2019. Among the participants who reported some

farming or snow-removal time, median farming and snow-removal time (minutes per day) was 90.0 and 64.3 for men and 85.7 and 51.4 for women, respectively. Ordinal logistic regression

analysis showed that longer time farming was associated with greater happiness and _ikigai_ in men (adjusted odds ratio for first vs. fourth quartile: happiness = 1.17, 95% confidence

interval [CI] = 1.01, 1.35; _ikigai_ = 1.29, 95% CI = 1.10, 1.50), and also in women (adjusted odds ratio for first vs. fourth quartile: happiness = 1.17, 95% CI = 1.001, 1.36; _ikigai_ =

1.42, 95% CI = 1.20, 1.67). More snow-removal time was inversely associated with happiness and with _ikigai_ in women only (adjusted odds ratio for first vs. fourth quartile: happiness =

0.75, 95% CI = 0.67, 0.85; _ikigai_ = 0.78, 95% CI = 0.69, 0.88). Our findings showed that physical activity in rural life was associated with happiness and with _ikigai_, and gender

differences were observed in their associations with more snow-removal time. These results may be useful in helping to identify people in rural communities who are vulnerable in terms of

psychological well-being. SIMILAR CONTENT BEING VIEWED BY OTHERS URBANIZATION AND PHYSICAL ACTIVITY IN THE GLOBAL PROSPECTIVE URBAN AND RURAL EPIDEMIOLOGY STUDY Article Open access 06

January 2023 EXAMINING THE RURAL–URBAN DIFFERENTIALS IN YOGA AND MINDFULNESS PRACTICES AMONG MIDDLE-AGED AND OLDER ADULTS IN INDIA: SECONDARY ANALYSIS OF A NATIONAL REPRESENTATIVE SURVEY

Article Open access 13 December 2023 AN EMPIRICAL STUDY ON SMART CITY CONSTRUCTION TO ENHANCE RESIDENTS’ PARTICIPATION IN PHYSICAL ACTIVITY Article Open access 16 November 2024 INTRODUCTION

“Happy people live longer” is a longstanding idea in public health (Diener and Chan, 2011; Frey, 2011). Happiness, or more broadly subjective well-being, has been shown to be positively

associated with longevity and physical health (Diener and Chan, 2011; Frey, 2011; Howell, 2009; Veenhoven, 2008). In general, happiness can be described as a pleasant feeling or positive

emotion and is influenced by interpersonal relationships in daily life. FACTORS ASSOCIATED WITH SUBJECTIVE WELL-BEING A wide array of factors is known to contribute to subjective well-being

including happiness, such as genetics, personality, and socioeconomic status (Johnson and Acabchuk, 2018; Steptoe, 2019), and various potential determinants of subjective well-being have

been investigated in countries worldwide (Steptoe et al., 2015; Adesanya et al., 2017). Subjective well-being can be conceptualised as culturally unique and shaped by cultural values and

beliefs (Fulmer et al., 2010; Karasawa et al., 2011; Miyamoto et al., 2019). Diener and Diener (1995) found a stronger correlation between subjective well-being and self-esteem in

individualistic nations, such as the United States and Canada, than in collectivistic nations, such as Asian countries including Japan, in a study of cross-cultural differences in predictors

of subjective well-being. The predictors of subjective well-being in the United States, an independent culture, were disengaging emotions (e.g., pride), whereas those in Japan, an

interdependent culture, were engaging emotions (e.g., friendly feelings) (Kitayama et al., 2006). In Asia, a Chinese study (_n_ = 301) of individuals aged 60 years or older living in rural

and urban areas and a Japanese study (_n_ = 2730) of adults aged 40–75 years living in the community found that social relationships and social capital had a greater impact on happiness (Yu

et al., 2019; Tsuruta et al., 2019). THE CONCEPT OF _IKIGAI_ IN JAPAN In Japan, the culturally specific term _ikigai_ is believed to be the most common indicator of well-being (Nakanishi,

1999). It is the policy of the Japanese government to create a society in which each individual can fulfil their _ikigai_ (Prime Minister’s Office of Japan, 2019). Although the English

language cannot precisely capture the nuance of _ikigai_, it basically means having a purpose in life or the sense that life is worth living (Lomas, 2016). _Ikigai_ can be used to describe

specific experiences that include future-oriented actions and confer a sense of worth and happiness, as well as the sense of fulfilment and joy that is derived from the cognitive evaluation

of such experiences (Maeda et al., 1979). The well-being of Japanese people can be understood as encompassing both happiness and _ikigai_. When the subjective well-being of Japanese people

is divided into hedonic and eudaimonic well-being, feelings of happiness are categorised as hedonic well-being, whereas feelings of _ikigai_ are categorised as eudaimonic well-being (Kumano,

2018). _Ikigai_ has been considered to be an important factor in longevity (Alimujiang et al., 2019; Seki, 2001) and has been documented in Japanese studies to be associated with functional

disability in the elderly as well as all-cause, external-cause, and cardiovascular mortality (Koizumi et al., 2008; Mori et al., 2017; Tanno et al., 2009). In addition, _ikigai_ has been

associated with family relationships, perception of good health, and social role fulfilment among older residents in rural communities (Hasegawa et al., 2003). _Ikigai_ may also be

applicable to non-Japanese cultures (Martela and Steger, 2016). As previous studies have clarified structural aspects of well-being from a cultural perspective, clarifying the concept of

_ikigai_ could have significance for understanding how psychological well-being can be maintained, regardless of cultural differences. PHYSICAL ACTIVITY AS A PREDICTOR OF SUBJECTIVE

WELL-BEING RURAL AND URBAN REGIONAL VARIATIONS IN PHYSICAL ACTIVITY Previous studies have found evidence that physical activity is associated with better health and psychological well-being

(Ekelund et al., 2016; Steven et al., 2006; Warburton and Bredin, 2019). Meanwhile, physical activity varies between urban and rural areas due to environmental factors, such as the built

environment, weather, and the community (Chan et al., 2006; Hermosillo-Gallardo et al., 2017; Lee et al., 2009). According to a study using data from the population-based International

Collaborative Study of Cardiovascular Disease in Asia, which assessed physical activity as vigorous activity, moderate activity, light activity, watching television, other sedentary

activities, and inactivity/sleeping in 15,540 representative samples (aged 35 to 74 years) from urban and rural areas, rural residents in China were more likely to be physically active

compared with urban residents (Muntner et al., 2005). A US study based on data from 178,161 respondents to the 2000 Behavioural Risk Factor Surveillance System found that achieving a

recommended physical activity level was associated with degree of urbanisation and that higher non-leisure-time activity levels were observed in rural areas than in urban areas (Martin et

al., 2005). These differences may reflect the built environment of neighbourhoods and regional differences in physical activity infrastructure and recreational opportunities (Carlson et al.,

2018). In addition, related cost and safety concerns may be barriers to physical activity (Moore et al., 2010). SIGNIFICANCE OF NON-LEISURE-TIME PHYSICAL ACTIVITY FOR DAILY LIFE AND HEALTH

Regular physical activity is distinguished from leisure-time and non-leisure-time physical activity. Leisure-time physical activity includes physical activities such as exercise and

recreation that are performed in any context other than those associated with one’s job, housework, and transportation, whereas non-leisure-time physical activity includes physical

activities associated with one’s occupations, housework, and transportation. Although many related studies have focused exclusively on leisure-time physical activity, the majority of

physical activity in middle-aged and older adults consists of non-leisure-time physical activity (Dong et al., 2004; Phongsavan et al., 2004). Data from the National Human Activity Pattern

Survey in the US found that leisure-time physical activity accounted for only about 5% of the population’s total energy expenditure (_n_ = 7515, aged 18 years or older) (Dong et al., 2004).

In addition, previous studies found that non-leisure-time physical activity consistently reduced substantial mortality risk in the US adult population, but leisure-time physical activity did

not (Arrieta and Russell, 2008; Davis et al., 1994). Similarly, an independent positive association was found between non-leisure-time physical activity and longevity among older Taiwanese

living in Tainan City (876 community-dwelling individuals aged 65 or older) (Lin et al., 2011). THE PRESENT STUDY: PHYSICAL ACTIVITY IN RURAL LIFE AND SUBJECTIVE WELL-BEING Farming activity

is affected by agricultural cycles and neighbourhood greenspace, and snow removal requires snow accumulation. Neighbourhood greenspace could contribute to the development of neighbourhood

social cohesion, which has been proven to benefit people’s health (Twohig-Bennett and Jones, 2018) and lead to a general sense of well-being due to the attractiveness of the living

environment (Brown et al., 2013). However, no study has investigated the relationship between snow removal and well-being, and little is known about the relationship between these daily

physical activities and _ikigai_. To reveal the relationship between physical activity and subjective well-being in a community, culture-specific terms for well-being such as _ikigai_ should

be considered, as should important contributors to daily living activities such as farming activity and snow removal. FARMING ACTIVITIES AND SNOW REMOVAL IN UONUMA, JAPAN In this study, we

focused on the area in and around the city of Uonuma, in Niigata Prefecture, Japan, which we took to be representative of areas with abundant greenspace and snow accumulation in the

corresponding seasons. Uonuma is located in a rural area in the south-central part of Niigata Prefecture, in north-eastern Japan. Although detailed characteristics of this area are described

in the “Methods” section, its topography and climate result in abundant snow accumulation and subsequently abundant water from snowmelt, making the area a leading producer of rice in Japan.

To our knowledge, no other part of Japan has such an even balance between farming and snowfall, so the Uonuma area is valuable because both farming activity and snow removal can be studied

as daily physical activities. PURPOSE OF THE PRESENT STUDY Against this backdrop, this study aimed to examine the relationship between physical activity and subjective well-being in terms of

happiness and _ikigai_, focusing on farming activity and snow removal carried out by Uonuma residents. The study is based on data from the Uonuma cohort study, a large cross-sectional

questionnaire survey conducted in the Uonuma area. Using these data, this paper explores the characteristics of farming activity and snow removal and tests the hypothesis that physical

activity in rural life, particularly, farming activity and snow removal, would affect subjective well-being in terms of happiness and _ikigai_ in community-dwelling Japanese adults. METHODS

STUDY SETTING This study was based on cross-sectional data from the Uonuma cohort study, which was a population-based prospective cohort study that started in 2012 to 2014 in the Uonuma area

of Niigata Prefecture, Japan. The methods of the Uonuma cohort study have been described in detail previously (Kabasawa et al., 2020). In the present study, we focused on Minamiuonuma City

and Uonuma City in Niigata, Japan. Baseline surveys of residents (aged ≥ 40 years) living in Minamiuonuma City were conducted in fiscal years 2012 (Muikamachi area) and 2013 (Shiozawa-Yamato

area); a baseline survey of residents living in Uonuma City was conducted in fiscal year 2014. At baseline, the Uonuma cohort study invited all 61,762 Minamiuonuma City and Uonuma City

residents aged ≥40 years to complete a questionnaire and ultimately received consent from 39,761 (64.4%). Between October and November of the baseline survey year, self-administered

questionnaires in sealed envelopes were distributed to the residents and collected by hand in cooperation with the administrative district manager of each city. Some questionnaires were

mailed subsequently. Informed consent was received from all participants. The study protocol was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of Niigata University (approval numbers 2012–1403

and 2013–1640). Briefly, the characteristics of this area are as follows. Minamiuonuma City and Uonuma City are located in the Uonuma Basin (lat. 37° N and long. 139° E) and the annual

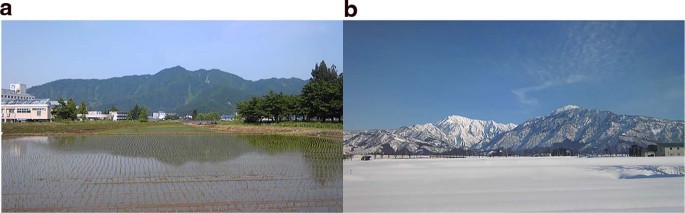

average temperature was 10–11 °C at the time of the study. This area is the leading producer of rice in Japan and its landscape is usually green from spring to fall (Fig. 1a) but turns white

in the winter with approximately 3–5 m of snow accumulation (one winter saw approximately 10 m of snow accumulation) (Fig. 1b). The Uonuma Basin has arable land and forests, which account

for ~10% and 60% of Minamiuonuma City, and ~4% and 80% of Uonuma City, respectively (Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries, 2017). The area has abundant snow accumulation almost

every year due to seasonal winds from Siberia that blow over the warm waters of the Sea of Japan and then hit the Echigo mountains, thereby bringing abundant snow to the area. Snowmelt leads

to a stable supply of water and a favourable soil temperature during the summer, making the area ideal for. Minamiuonuma City and Uonuma City had a population of 58,568 (population density,

101.2 people/km2) and 37,352 (39.5 people/km2) as of 2015, respectively, compared with 810,157 (1115.3 people/km2) in Niigata City, the prefectural capital. The proportion of elderly

residents (aged ≥ 65 years) was 32.9% in Minamiuonuma City and 29.2% in Uonuma City, compared with 27.0% in Niigata City and 26.7% in Japan nationwide. Approximately 10.3% of the residents

living in the area work as farmers, which is more than the Japanese national average of 3.4% (Statistics Bureau of Japan, 2015). A flowchart of the study enrolment process is shown in Fig.

2. Participants were excluded from the study if they reported a history of depression, had a prescription for an antidepressant, or had incomplete questionnaire data. Finally, the total

number of analysed subjects was 31,848 for happiness and 31,785 for _ikigai_. MEASURES All participants were given self-administered questionnaires covering demographic characteristics,

height, weight, smoking status, alcohol intake, and history of diseases. Sociodemographic characteristics included living status (alone or living with others), employment status (unemployed

or employed), and education level. Occupation was classified as “farmer or fisher” or other. A summary of smoking status and alcohol intake was also obtained. Body mass index (BMI) was

calculated by dividing self-reported body weight (kg) by self-reported height squared (m2). Participants with extremely high or low BMI (three standard deviations [SD] from the mean BMI for

each sex) were excluded. History of chronic conditions (self-reported malignancy of any type, cardiovascular disease, stroke, hypertension, diabetes, asthma, etc.) was summarised as whether

a participant had any chronic disease or not. Total physical activity was assessed as the sum of metabolic equivalent of task (MET) × hours per day performing each daily and leisure

activity. MET intensities were 4.5 given for vigorous physical work or strenuous exercise, 2.0 for walking or standing, 1.5 for sedentary activities, and 1.0 for sleeping. This index has

been validated previously (Kikuchi et al., 2018). PHYSICAL ACTIVITY IN RURAL LIFE The average time per week performing farming activity from May through November (green season) and

performing snow removal from December through April (snow season) were assessed. In the questionnaire, the participants were asked the following, with no restriction on the type of farming

activity or snow removal: “How many minutes per week do you spend on farming activity?” and “How many minutes per week do you spend on snow removal?” The total time spent on each activity

type per week was calculated and then converted to time spent per day. Then, participants who responded with farming activity or snow-removal times that were excessive (more than 7 days a

week or more than 1440 min per day including sleeping time) were excluded. To validate the correlation between time spent on each activity type and intensity, participants in fiscal year

2014 were also asked about activity intensity (vigorous, moderate, or light). Responses from 5305 participants (3108 men and 2197 women) were obtained for farming activity and 7527

participants (4563 men and 2964 women) for snow removal. The total amount of activity was estimated as METs × hours per day by calculating time spent on each activity type per day multiplied

by its MET intensity (for farming and snow removal, respectively): vigorous (6.0, 7.5), moderate (4.3, 5.3), and light (2.8, 2.5). Spearman’s correlation coefficients for total time spent

performing farming activity vs. total MET score (METs h/day), vigorous activity time, moderate activity time, and light activity time were 0.71, 0.54, 0.50, and 0.52 for men and 0.64, 0.45,

0.53, and 0.30 for women, respectively. Those for snow removal were 0.78, 0.58, 0.41, and 0.24 for men and 0.72, 0.54, 0.36, and 0.10 for women, respectively. HAPPINESS AND _IKIGAI_ Separate

questions addressing happiness and _ikigai_ were asked in the questionnaire. Participants were asked to subjectively respond to the questions, “To what degree do you feel happy?” and “To

what degree do you have _ikigai_?” Responses were given on a 4-point scale. Responses for happiness were coded as very happy (1), happy (2), neither happy nor unhappy (3), and unhappy (4).

Responses for _ikigai_ were coded as have a lot of _ikigai_ (1), have some _ikigai_ (2), have a little _ikigai_ (3), and have no _ikigai_ (4) (Table 1). STATISTICAL ANALYSIS Data were

analysed between April and November 2019 using SAS statistical software (version 9.4, SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC). Characteristics of the participants according to quartile of time for

farming activity and snow removal by sex are presented as means ± SD, medians (interquartile range), or numbers (percentage) (Tables S1 and S2). Physical activity for farming activity and

snow removal was classified either as none or according to quartile of total time spent for each activity per day. Differences across quartiles were assessed by one-way analysis of variance

for continuous variables and the chi-square test for categorical variables. The association between each physical activity and degree of happiness or _ikigai_ was assessed using an ordinal

logistic regression model (McCullagh, 1980; Stewart et al., 2019). This model is similar to conventional logistic regression approaches except that an ordered categorical variable is treated

as a dependent variable. Although the interpretation of the estimated regression slope is different and more complicated than that of conventional regression approaches, the assumption of

intervals between scoring categories is no longer needed. Odds ratios (ORs) were estimated as crude, age-adjusted, and multivariable-adjusted values (Tables 2, 3, S3, and S4). The details of

adjustment variables are shown in Table 1. Trend analysis was performed according to quartile of each physical activity except the “none” category. To ensure the robustness of the

relationship with farming activity for those who were not farmers or fishers by occupation, similar ordinal logistic regression analysis calculating ORs of happiness and _ikigai_ for farming

activity was performed in the subpopulation excluding participants who were working as a farmer or fisher. RESULTS The entire population that was analysed comprised men with a mean age of

62.5 (SD, 12.2) years and women with a mean age of 62.9 (SD, 12.8) years. After excluding participants who spent no time on farming activity or snow removal, the median time for farming

activity and snow removal was 90.0 min/day (_n_ = 8631) and 64.3 min/day (_n_ = 14,054) for men and 85.7 min/day (_n_ = 6277) and 51.4 min/day (_n_ = 10,242) for women, respectively. The

distribution of happiness and _ikigai_ according to quartile of time spent on farming activity and snow removal by sex are shown in Fig. 3. The percentage of participants who answered very

happy or happy was higher among those who reported spending a long time on farming activity than among those who reported spending a short or no time on farming activity in both sexes. A

higher percentage of women who answered neither unhappy nor happy or unhappy was observed among those who reported no time spent on farming activity and those in the longest quartile of time

spent on snow removal than among those in the shortest quartile (Fig. 3a). As for _ikigai_, the percentage of participants who answered that they had some or a lot of _ikigai_ was higher

among those who reported spending a long time on farming activity than among those who reported a short or no time spent on farming activity in both sexes. The highest percentage of

participants who answered that they had little or no _ikigai_ was observed among those who reported spending no time on snow removal in men (Fig. 3b). Men who spent more time on farming

activity were likely to be older, be married, have higher total physical activity, have a chronic disease, have a lower education level, be unlikely to be unhappy, be a current smoker, have

no _ikigai_, and live alone. Women who spent more time on farming activity were likely to be older, be non-drinkers, have higher total physical activity, have a lower education level, and be

unlikely to be a current smoker (Table S1; all _P_ < 0.05). For snow removal characteristics, men who spent no time on snow removal were likely to be older, be thinner, be unhappy, be a

non-drinker, be unemployed, have lower total physical activity, have a chronic disease, live alone, have no _ikigai_, be unlikely to be a current smoker, be a farmer or fisher, and be

married. Women who spent no time on snow removal were likely to be older, be a non-drinker, be very happy, be unemployed, have lower total physical activity, have a chronic disease, not be a

current smoker, and not be a farmer or fisher (Table S2; all _P_ < 0.05). Men who reported spending more time on snow removal than those who reported a shorter time spent on snow removal

were likely to be older, be a farmer or fisher, be unemployed, be married, have higher total physical activity, have a chronic disease, and have a lower education level. Women who reported

spending more time on snow removal than those who reported a shorter time spent on snow removal were more likely to be older, be unhappy, be a non-smoker, be a non-drinker, be a farmer or

fisher, be unemployed, have higher total physical activity, have a chronic disease, live alone, and have a lower education level, and were less likely to be married (Table S2). The

association between each physical activity and happiness is shown in Tables 2 and S3. In the multivariable ordinal logistic regression analysis, the fourth quartile of farming activity was

associated with happiness in men and women (adjusted odds ratio for the first vs. fourth quartile of time spent on farming activity for men = 1.17, 95% confidence interval [CI] = 1.01, 1.35;

women = 1.17, 95% CI = 1.001, 1.36) (Fig. 4a). However, more time spent on snow removal was inversely associated with happiness in women only (_P_-trend < 0.001). The association between

each physical activity and _ikigai_ is shown in Tables 3 and S4. The fourth quartile of farming activity was associated with _ikigai_ in men and women (adjusted odds ratio for the first vs.

fourth quartile of farming activity for men = 1.29, 95% CI = 1.10, 1.50; women = 1.42, 95% CI = 1.20, 1.67) (Fig. 4b). Compared with participants who reported snow removal, those who

reported no snow removal exhibited a negative association with _ikigai_ in men and women (adjusted odds ratio for the first quartile of time spent on farming activity vs. no time spent on

farming activity for men = 0.74, 95% CI = 0.65, 0.84; women = 0.85, 95% CI = 0.77, 0.95) (Fig. 4b). Similar to the association with happiness, more time spent on snow removal was inversely

associated with having _ikigai_ in women only (_P_-trend < 0.001). Similar ordinal logistic regression analysis was performed for the participants who did not work as farmers or fishers.

In this multivariable model, the population that was analysed comprised 12,724 men and 14,752 women for happiness; 12,725 men and 14,704 women for _ikigai_. Adjusted ORs of happiness for the

first vs. fourth quartiles of farming activity were 1.06 (95% confidence interval [CI] = 0.91, 1.24, _P_-trend = 0.432) in men and 1.17 (95% CI = 1.01, 1.35, _P_-trend = 0.678) in women.

Those of having _ikigai_ for the first vs. fourth quartile of farming activity were 1.16 (95% CI 0.98, 1.37, _P_-trend = 0.123) in men, and 1.34 (95% CI = 1.14, 1.57, _P_-trend = 0.171) in

women. DISCUSSION This study identified not only positive associations of more time farming with happiness and _ikigai_ in both men and women but also inverse associations of more

snow-removal time with happiness and _ikigai_ in women only. Furthermore, not engaging in snow removal was demonstrated to be negatively associated with _ikigai_ in men and women. This study

provides a unique perspective on gender differences in the association between rural physical activity and subjective well-being. ASSOCIATIONS BETWEEN FARMING ACTIVITY AND SUBJECTIVE

WELL-BEING Farming activity generally refers to plant-based activities such as growing fruits, vegetables, or other crops. In rural areas, farming activity is considered a type of community

practice that can provide an opportunity for constructing social relationships. In the mental healthcare field, plant-based activities are used in horticultural therapy to promote social

skills, self-esteem, and time spent on leisure activities (Smith, 1998). Among Japanese studies, Machida (2019) reported a positive association of home gardening with happiness and reason

for living, which could be interpreted as _ikigai_, in Japanese elderly. Also, some studies have indicated a positive relationship between plant-based activities and mental health, such as

psychological well-being, cognitive protection, and decreased sadness and anxiety (Infantino, 2004; Shiue, 2016; Tournier and Postal, 2014). Considering these findings together with the

present results, plant-based activities including farming activity could have beneficial effects on subjective well-being, particularly happiness and _ikigai_, in both men and women.

ASSOCIATIONS BETWEEN SNOW REMOVAL AND SUBJECTIVE WELL-BEING Snow removal and farming activity are similar in terms of providing an opportunity to engage in social relationships and physical

activity; however, their effects were opposite for happiness and _ikigai_ in this study. The difference between characteristics of farming activity and snow removal might have caused this

result; that is, snow removal is considered an additional but necessary task for maintaining daily life, whereas farming activity is considered a vocation for farmers but a freely selectable

activity for non-farmers. The varied relationship between farming activity and snow removal with subjective well-being could be positively influenced by economic benefits. In other words,

farming activity such as growing vegetables and fruits could provide economic incentives for both sexes. Meanwhile, snow removal in the Uonuma area can provide part-time work in winter to

supplement wages but such an opportunity would not traditionally be applied to women. GENDER DIFFERENCES IN ASSOCIATIONS BETWEEN SNOW REMOVAL AND SUBJECTIVE WELL-BEING This study observed

clear gender differences in the relationship between snow removal and subjective well-being; namely, inverse associations were observed only in women. The traditional Japanese norm is ”men

at work and women at home”, which may negatively affect women’s subjective well-being if women feel trapped by gender role fulfilment. Moreover, societal expectations could worsen women’s

feelings of daily pressure due to gender role fulfilment in traditionally male-dominated societies (Batz-Barbarich et al., 2018). In terms of biological factors, it is to be expected that

men and women have different stamina and patience to remove snow. Although physical activity plays an important role in subjective well-being, it is known to vary according to content and

intensity level (Brajša-Žganec et al., 2011; Zhang et al., 2017). Zhang et al. (2015) found that men tended to engage in more diverse types of leisure activities than women; in other words,

men had greater freedom in selecting and participating in various activities than women due to their differing degrees of expected fulfilment of family duties. Taken together, when snow

removal is added to women’s family duties, gender role fulfilment may become a stressful experience because it takes away from women’s freedom, leading to reduced happiness (Segar et al.

2017). OTHER DIFFERENCES IN ASSOCIATIONS BETWEEN PHYSICAL ACTIVITY AND SUBJECTIVE WELL-BEING Interestingly, this study found that not engaging in snow removal was inversely associated with

_ikigai_, and a marginal negative association of no time spent engaged in farming activities with happiness as well as _ikigai_. This may relate to differences in background characteristics

between participants who do and do not engage in snow removal and farming activities. For example, those who did not engage in snow removal were likely to be older, have a chronic disease,

be unemployed, live alone, be never smokers, and be non-drinkers; those who reported no time spent on farming activity were likely to be current smokers, be unmarried, and have a higher

education level. Moreover, men feeling less subjective well-being when they do not or cannot perform snow removal may reflect that men feel economic incentives are insufficient and that they

are not sufficiently fulfilling their expected gender role in the community. Not engaging in snow removal seems to be affected by physical limitations and low motivation for that activity,

whereas no time spent on farming activities may relate to other activities such as one’s job. In addition, one’s drive and adaptability may affect this difference because low-intensity

activity and the interchangeability of moderate and vigorous activity are important for improving life satisfaction (Wicker and Frick, 2017). DIFFERENCE BETWEEN HAPPINESS AND _IKIGAI_ IN THE

RELATIONSHIP WITH PHYSICAL ACTIVITY In this study, differences between happiness and _ikigai_ were observed only in the absence of snow removal. This might mean that snow removal

contributes to _ikigai_ in the Uonuma area, but it might lead to less _ikigai_ for women if it takes up more time than they can bear for their well-being. In a previous study that assessed

factors associated with _ikigai_ among older public temporary employees, physical condition and socioeconomic factors were significant factors for men, and family relations and life

satisfaction were significant for women (Shirai et al., 2006). Given that snow removal might relate to socioeconomic factor for men and family duties for women, not removing snow could lead

to compromised _ikigai_ in the Uonuma area, where abundant snowfall is a part of life. Whether or not to farm is a decision that can be decided by the individual, but most people have no

choice but to remove snow. Therefore, not removing snow may lead to less _ikigai_ but not less happiness, because happiness is considered from a hedonic perspective whereas _ikigai_ is

considered from a eudaimonic perspective. FUTURE IMPLICATION OF THE STUDY The results of the present study hold implications for future research because the study design could be applied to

other places where physical activity is essential for people’s lives. Although snow removal is specific to the study area, similarly vigorous physical activity essential for living such as

hunting and travelling long distances in the scorching heat to get water. Thus, our finding of a clear negative association between longer time spent removing snow and subjective well-being

could be applied to these hard physical activities, especially for women. Our results also suggest the need to consider those who do not or cannot perform such physical activities as

psychologically vulnerable populations who might be in need of assistance from the community. Vuong (2018) argued that modern society faces challenges in terms of the balance between the

cost and benefit of science’s contribution to society, but also stated that “the real value of science is in improving quality of life”. To achieve psychological well-being in the community,

performing chores and engaging in other physical activities that benefit the community, as well as practising gratitude and volunteering one’s time can all be beneficial (Jackowska et al.,

2016; Borgonovi, 2008). From the perspective of policy efforts to maintain or improve subjective well-being in the community, it may be useful to address environmental factors, such as

providing opportunities for farming activity and support so that people can perform snow removal within the amount of time they would like to spend. Thus, future work may involve a

longitudinal evaluation of the association found in this study, as well as the specific forms or theories of measures such as social support frameworks that are culturally appropriate and

effective for improving happiness and _ikigai_ in rural communities. Many more studies are needed to determine effective approaches for achieving subjective well-being in rural communities

along with understanding relevant environmental factors and traditional social norms. The factors identified in this study might provide anchors for interventions or other ideas for

achieving subjective well-being in rural communities. LIMITATIONS A strength of the present study is that it is the first report to assess the relationship of physical activity in rural life

(farming activity and snow removal) with happiness and _ikigai_ separately in a large-scale population. However, the study also has some limitations. First, data were all self-reported,

meaning that misclassification bias may have occurred. Second, this study was conducted in a Japanese rural area. Therefore, there is potential sociocultural bias due to the selection of the

study area. Within the study area, even though there was adjustment for the survey area by year, farming activity and snow removal depend on weather, which differs from one year to the

next, and other environmental factors. Also, our results may be affected by uncertainty in the impacts of climate change. Third, although there was adjustment for major confounding factors

of happiness and _ikigai_, we could not control for unmeasured potential confounders, such as personality and disability. Finally, the study design was cross-sectional, so causal

relationships could not be determined. CONCLUSION This study revealed the association of physical activity in rural life with subjective well-being in terms of happiness and _ikigai_ in

community-dwelling adults. Notably, a gender difference was found, with men and women exhibiting different associations of more snow-removal time with happiness and _ikigai_. Considering our

findings together with previous studies, farming activity could be protective for psychological health in rural life. Meanwhile, this study suggests that physical activity in rural life

induced by environmental stress such as snow removal may negatively affect subjective well-being. This may provide indicators for who in the rural community should be considered vulnerable

in terms of psychological well-being. DATA AVAILABILITY All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article. REFERENCES * Adesanya AO, Rojas BM, Darboe A,

Beogo I (2017) Socioeconomic differential in self-assessment of health and happiness in 5 African countries: finding from World Value Survey. PLoS ONE 12(11):e0188281 Article CAS Google

Scholar * Alimujiang A, Wiensch A, Boss J, Fleischer NL, Mondul AM, McLean K, Mukherjee B, Pearce CL (2019) Association between life purpose and mortality among US adults older than 50

years. JAMA Netw Open 2(5):e194270 Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Arrieta A, Russell LB (2008) Effects of leisure and non-leisure physical activity on mortality in U.S.

adults over two decades. Ann Epidemiol 18(12):889–895 Article PubMed Google Scholar * Batz-Barbarich C, Tay L, Kuykendall L, Cheung HK (2018) A meta-analysis of gender differences in

subjective well-being: estimating effect sizes and associations with gender inequality. Psychol Sci 29(9):1491–1503 Article PubMed Google Scholar * Borgonovi F (2008) Doing well by doing

good: the relationship between formal volunteering and self-reported health and happiness. Soc Sci Med 66:2321–2334 Article PubMed Google Scholar * Brajša-Žganec A, Merkaš M, Šverko I

(2011) No quality of life and leisure activities: how do leisure activities contribute to subjective well-being? Soc Indic Res 102:81–91 Article Google Scholar * Brown B, Perkins DD, Brown

G (2013) Place attachment in a revitalizing neighborhood: individual and block levels of analysis. J Environ Psychol 23:259–271 Article Google Scholar * Carlson JA, Frank LD, Ulmer J,

Conway TL, Saelens BE, Cain KL, Sallis JF (2018) Work and home neighborhood design and physical activity. Am J Health Promot 32(8):1723–1729 Article PubMed Google Scholar * Chan CB, Ryan

DA, Tudor-Locke C (2006) Relationship between objective measures of physical activity and weather: a longitudinal study. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act 3:21 Article PubMed PubMed Central

Google Scholar * Davis MA, Neuhaus JM, Moritz DJ et al. (1994) Health behaviors and survival among middle-aged and older men and women in the NHANES I Epidemiologic Follow-up Study. Prev

Med 23(3):369–376 Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Diener E, Chan MY (2011) Happy people live longer: subjective well-being contributes to health and longevity. Appl Psychol Health

Well Being 3(1):1–43 Article Google Scholar * Diener E, Diener M (1995) Cross-cultural correlates of life satisfaction and self-esteem. J Pers Soc Psychol 68(4):653–663 Article CAS

PubMed Google Scholar * Dong L, Block G, Mandel S (2004) Activities contributing to total energy expenditure in the United States: results from the NHAPS study. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act

1(1):4 Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Ekelund U, Steene-Johannessen J, Brown WJ, Lancet Physical Activity Series 2 Executive Committe; Lancet Sedentary Behaviour Working

Group. et al. (2016) Does physical activity attenuate, or even eliminate, the detrimental association of sitting time with mortality? A harmonised meta-analysis of data from more than 1

million men and women. Lancet 388(10051):1302–1310 Article PubMed Google Scholar * Frey BS (2011) Psychology. Happy people live longer. Science 331(6017):542–543 Article CAS PubMed ADS

Google Scholar * Fulmer CA, Gelfand MJ, Kruglanski AW et al. (2010) On ‘feeling right’ in cultural contexts: how person-culture match affects self-esteem and subjective well-being.

Psychol Sci 21:1563–1569 Article PubMed Google Scholar * Hasegawa A, Fujiwara Y, Hoshi T et al. (2003) Koreisyaniokeru ikigai no tiikisa –Kazokukousei, sintaijoukyou narabini seikatukinou

tono kanren (Regional differences in ikigai (reason(s) for living) in elderly people). Nihon Ronen Igakkai Zasshi 40(4):390–396 Article PubMed Google Scholar * Hermosillo-Gallardo ME,

Jago R, Sebire SJ (2017) The associations between urbanicity and physical activity and sitting time in Mexico. J Phys Act Health 14(3):189–194 Article PubMed Google Scholar * Howell RT

(2009) Review: positive psychological well-being reduces the risk of mortality in both ill and healthy populations. Evid Based Ment Health 12(2):41 Article PubMed Google Scholar *

Infantino M (2004) Gardening: a strategy for health promotion in older women. J N Y State Nurses Assoc 35:10–17 PubMed Google Scholar * Jackowska M, Brown J, Ronaldson A et al. (2016) The

impact of a brief gratitude intervention on subjective well-being, biology and sleep. J Health Psychol 21(10):2207–2217 Article PubMed Google Scholar * Johnson BT, Acabchuk RL (2018) What

are the keys to a longer, happier life? Answers from five decades of health psychology research. Soc Sci Med 196:218–226 Article PubMed Google Scholar * Kabasawa K, Tanaka J, Nakamura K

et al. (2020) Study design and baseline profiles of participants in the Uonuma CKD cohort study in Niigata, Japan. J Epidemiol 30(4):170–176 Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

* Karasawa M, Curhan KB, Markus HR et al. (2011) Cultural perspectives on aging and well-being: a comparison of Japan and the United States. Int J Aging Hum Dev 73:73–98 Article PubMed

PubMed Central Google Scholar * Kikuchi H, Inoue S, Lee IM et al. (2018) Impact of moderate-intensity and vigorous-intensity physical activity on mortality. Med Sci Sports Exerc

50(4):715–721 Article PubMed Google Scholar * Kitayama S, Mesquita B, Karasawa M (2006) Cultural affordances and emotional experience: socially engaging and disengaging emotions in Japan

and the United States. J Pers Soc Psychol 91(5):890–903 Article PubMed Google Scholar * Koizumi M, Ito H, Kaneko Y, Motohashi Y (2008) Effect of having a sense of purpose in life on the

risk of death from cardiovascular diseases. J Epidemiol 18(5):191–196 Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Kumano M (2018) On the concept of well-being in Japan: feeling

shiawase as hedonic well-being and feeling Ikigai as eudaimonic well-being. Appl Res Qual Life 13:419–433 Article Google Scholar * Lee IM, Ewing R, Sesso HD (2009) The built environment

and physical activity levels: the Harvard Alumni Health Study. Am J Prev Med 37(4):293–298 Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Lin YP, Huang YH, Lu FH et al. (2011)

Non-leisure time physical activity is an independent predictor of longevity for a Taiwanese elderly population: an eight-year follow-up study. BMC Public Health 11:428 Article PubMed

PubMed Central Google Scholar * Lomas T (2016) Towards a positive cross-cultural lexicography: enriching our emotional landscape through 216 ‘untranslatable’ words pertaining to

well-being. J Posit Psychol 11(5):546–558 Article Google Scholar * Machida D (2019) Relationship between community or home gardening and health of the elderly: a web-based cross-sectional

survey in Japan. Int J Environ Res Public Health 16(8). https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16081389. * Maeda T, Asano H, Taniguchi K (1979) Rojin no shukanteki kohukukan no kenkyu (Research on

the subjective happiness of the elderly). Soc Geron 11:15–31 Google Scholar * Martela F, Steger MF (2016) The three meanings of meaning in life: distinguishing coherence, purpose, and

significance. J Posit Psychol 11(5):531–545 Article Google Scholar * Martin SL, Kirkner GJ, Mayo K et al. (2005) Urban, rural, and regional variations in physical activity. J Rural Health

21(3):239–244 Article PubMed Google Scholar * McCullagh P (1980) Regression models for ordinal data. J R Stat Soc B 42:109–142 MathSciNet MATH Google Scholar * Ministry of Agriculture,

Forestry and Fisheries, Tokyo, Japan (2017). http://www.maff.go.jp/ [Accessed 5 Sept 2019] * Miyamoto Y, Yoo J, Wilken B (2019) Well-being and health: a cultural psychology of optimal human

functioning. In: Cohen D, Kitayama S (eds) Handbook of Cultural Psychology. Guilford, New York, NY Google Scholar * Moore JB, Jilcott SB, Shores KA et al. (2010) A qualitative examination

of perceived barriers and facilitators of physical activity for urban and rural youth. Health Educ Res 25(2):355–367 Article PubMed Google Scholar * Mori K, Kaiho Y, Tomata Y et al.

(2017) Sense of life worth living (ikigai) and incident functional disability in elderly Japanese: The Tsurugaya Project. J Psychosom Res 95:62–67 Article PubMed Google Scholar * Muntner

P, Gu D, Wildman RP et al. (2005) Prevalence of physical activity among Chinese adults: results from the International Collaborative Study of Cardiovascular Disease in Asia. Am J Public

Health 95(9):1631–1636 Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Nakanishi N (1999) ‘Ikigai’ in older Japanese people. Age Ageing 28(3):323–324 Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

* Phongsavan P, Merom D, Marshall A et al. (2004) Estimating physical activity level: the role of domestic activities. J Epidemiol Community Health 58(6):466–467 Article CAS PubMed

PubMed Central Google Scholar * Prime Minister’s Office of Japan (2019) Ichi-oku soukatsuyaku shakai no jitsugen (Realization of the 100 million active society).

https://www.kantei.go.jp/jp/headline/ichiokusoukatsuyaku/. Accessed 30 Jul 2020 * Segar M, Taber JM, Patrick H et al. (2017) Rethinking physical activity communication: using focus groups to

understand women’s goals, values, and beliefs to improve public health. BMC Public Health 17(1):462 Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Seki N (2001) Hokoujikan, suiminjikan,

ikigai to koureisya no seimeiyogo no kanren ni kansuru kohohtokenkyu (Relationships between walking hours, sleeping hours, meaningfulness of life (ikigai) and mortality in the elderly:

prospective cohort study). Nihon Eiseigaku Zasshi 56(2):535–540 Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Shirai K, Iso H, Fukuda H et al. (2006) Factors associated with “Ikigai” among members

of a public temporary employment agency for seniors (Silver Human Resources Centre) in Japan; gender differences. Health Qual Life Outcomes 4:12 Article PubMed PubMed Central Google

Scholar * Shiue I (2016) Gardening is beneficial for adult mental health: Scottish Health Survey, 2012-2013. Scand J Occup Ther 23(4):320–325 Article PubMed Google Scholar * Smith DJ

(1998) Horticultural therapy: the garden benefits everyone. J Psychosoc Nurs Ment Health Serv 36:14–21 Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Statistics Bureau of Japan. Population Census

(2015) http://www.stat.go.jp/english/data/kokusei/index.html. Accessed 5 Sept 2019 * Steptoel A, Deaton A, Stone AA (2015) Subjective wellbeing, health, and ageing. Lancet 385(9968):640–648

Article Google Scholar * Steptoe A (2019) Happiness and Health. Annu Rev Public Health 40:339–359 Article PubMed Google Scholar * Steven RB, Matthew YW, Kwan BA (2006) Physical activity

is associated with better health and psychological well-being during transition to university life. J Am Coll Health 55(2):77–82 Article Google Scholar * Stewart G, Kamata A, Miles R et

al. (2019) Predicting mental health help seeking orientations among diverse undergraduates: an ordinal logistic regression analysis. J Affect Disord 257:271–280 Article PubMed Google

Scholar * Tanno K, Sakata K, Ohsawa M, JACC Study Group. et al. (2009) Associations of ikigai as a positive psychological factor with all-cause mortality and cause-specific mortality among

middle-aged and elderly Japanese people: findings from the Japan Collaborative Cohort Study. J Psychosom Res 67(1):67–75 Article PubMed Google Scholar * Tournier I, Postal V (2014) An

integrative model of the psychological benefits of gardening in older adults. Geriatr Psychol Neuropsychiatr Vieil 12:424–431 PubMed Google Scholar * Tsuruta K, Shiomitsu T, Hombu A et al.

(2019) Relationship between social capital and happiness in a Japanese community: a cross-sectional study. Nurs Health Sci 21(2):245–252 Article PubMed Google Scholar * Twohig-Bennett C,

Jones A (2018) The health benefits of the great outdoors: a systematic review and meta-analysis of greenspace exposure and health outcomes. Environ Res 166:628–637 Article CAS PubMed

PubMed Central Google Scholar * Veenhoven R (2008) Healthy happiness: effects of happiness on physical health and the consequences for preventive health care. J Happiness Stud 9:449–469

Article Google Scholar * Vuong Q (2018) The (ir)rational consideration of the cost of science in transition economies. Nat Hum Behav 2:5. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-017-0281-4 Article

PubMed Google Scholar * Warburton DER, Bredin SSD (2019) Health benefits of physical activity: a strengths-based approach. J Clin Med 8:12 Article Google Scholar * Wicker P, Frick B

(2017) Intensity of physical activity and subjective well-being: an empirical analysis of the WHO recommendations. J Public Health (Oxf) 39(2):e19–e26 Google Scholar * Yu R, Cheung O, Leung

J, Tong C, Lau K, Cheung J, Woo J (2019) Is neighbourhood social cohesion associated with subjective well-being for older Chinese people? The neighbourhood social cohesion study. BMJ Open

9(5):e023332 Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Zhang W, Feng Q, Liu L, Zhen Z (2015) Social engagement and health: findings from the 2013 survey of the shanghai elderly life

and opinion. Int J Aging Hum Dev 80(4):332–356 Article PubMed Google Scholar * Zhang W, Feng Q, Lacanienta J, Zhen Z (2017) Leisure participation and subjective well-being: exploring

gender differences among elderly in Shanghai, China. Arch Gerontol Geriatr 69:45–54 Article PubMed Google Scholar Download references ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This research was supported by the

government of Niigata Prefecture, Japan. The funder had no role in the study design, data collection, interpretation of the results, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript. In

this research work, we used a supercomputer at the Academic Centre for Computing and Media Studies, Kyoto University, Japan. We would like to express our gratitude to all the study

participants, healthcare providers, and members of our study group who assisted with this study. We also acknowledge the governments of Niigata Prefecture, Minami Uonuma City, and Uonuma

City for their valuable cooperation in conducting the Uonuma Cohort Study. We sincerely thank Dr. Joseph Green (University of Tokyo, retired) for discussions regarding data analysis. AUTHOR

INFORMATION AUTHORS AND AFFILIATIONS * Department of Health Promotion Medicine, Niigata University Graduate School of Medical and Dental Sciences, Niigata, Japan Keiko Kabasawa, Junta

Tanaka, Yumi Ito, Kinya Yoshida & Ichiei Narita * Division of Preventive Medicine, Niigata University Graduate School of Medical and Dental Sciences, Niigata, Japan Kaori Kitamura &

Kazutoshi Nakamura * Epidemiology and Prevention Group, Center for Public Health Sciences, National Cancer Center, Tokyo, Japan Shoichiro Tsugane * Division of Clinical Nephrology and

Rheumatology, Niigata University Graduate School of Medical and Dental Sciences, Niigata, Japan Ichiei Narita Authors * Keiko Kabasawa View author publications You can also search for this

author inPubMed Google Scholar * Junta Tanaka View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Yumi Ito View author publications You can also search for

this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Kinya Yoshida View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Kaori Kitamura View author publications You can

also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Shoichiro Tsugane View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Kazutoshi Nakamura View author

publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Ichiei Narita View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar CORRESPONDING

AUTHOR Correspondence to Keiko Kabasawa. ETHICS DECLARATIONS COMPETING INTERESTS The authors declare no competing interests. ADDITIONAL INFORMATION PUBLISHER’S NOTE Springer Nature remains

neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIALS RIGHTS AND PERMISSIONS OPEN ACCESS This

article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as

you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party

material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s

Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. Reprints and permissions ABOUT THIS ARTICLE CITE THIS ARTICLE Kabasawa, K., Tanaka, J., Ito, Y. _et al._

Associations of physical activity in rural life with happiness and _ikigai_: a cross-sectional study. _Humanit Soc Sci Commun_ 8, 46 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-021-00723-y

Download citation * Received: 17 February 2020 * Accepted: 11 January 2021 * Published: 15 February 2021 * DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-021-00723-y SHARE THIS ARTICLE Anyone you share

the following link with will be able to read this content: Get shareable link Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article. Copy to clipboard Provided by the Springer

Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative