The dynamic effect of trading between china and taiwan under exchange rate fluctuations

- Select a language for the TTS:

- UK English Female

- UK English Male

- US English Female

- US English Male

- Australian Female

- Australian Male

- Language selected: (auto detect) - EN

Play all audios:

ABSTRACT As an export-oriented economy, Taiwan’s export income can be easily influenced by internal and international economic factors, including the industrial production index (IPI) and

the exchange rate. With China being Taiwan’s largest recipient, Taiwan’s export income from China is extremely important to Taiwan’s economy. Therefore, this research investigates the

nonlinear relationship between the IPI of Taiwan and Taiwan’s export income from China with the application of a panel smooth transition regression (PSTR) model. In addition, the currency

exchange rate of RMB to NTD, which is the transfer variable, is used to examine the dynamic effect. The research period is monthly data ranging from January 2001 to February 2022. The

empirical results show that the effect of the IPI of Taiwan on Taiwan’s export income with China is dynamic. Moreover, with the existence of a threshold value, its influence changes as the

currency exchange rate of RMB to NTD varies over time. Finally, regardless of whether the currency exchange rate of RMB to NTD is above or below the threshold value, as the IPI of Taiwan

increases, Taiwan’s export income from China also increases, differing only in the degree of increase. SIMILAR CONTENT BEING VIEWED BY OTHERS THE COVID-19 PANDEMICS AND IMPORT DEMAND

ELASTICITIES: EVIDENCE FROM CHINA’S CUSTOMS DATA Article Open access 18 December 2023 HOW DOES INTER-PROVINCIAL TRADE PROMOTE ECONOMIC GROWTH? EMPIRICAL EVIDENCE FROM CHINESE PROVINCES

Article Open access 02 August 2024 THE DYNAMIC RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN TRADE OPENNESS, FOREIGN DIRECT INVESTMENT, CAPITAL FORMATION, AND INDUSTRIAL ECONOMIC GROWTH IN CHINA: NEW EVIDENCE FROM

ARDL BOUNDS TESTING APPROACH Article Open access 11 April 2023 INTRODUCTION Taiwan has been recognized as an “export-oriented economy” (Ghartey, 1993; Jin and Shih, 1995), and it has grown

from a predominantly agricultural country to a newly industrialized country in less than 40 years (Schive, 1995). Currently, Taiwan is one of the “Four Asian Tigers”, along with Hong Kong,

South Korea, and Singapore, which is a group of Southeast Asian countries that experienced extraordinary growth from 1965 to 1995 (Mascelluti, 2015). Although Taiwan’s economy has made

breakthroughs, China has become the fastest growing global economy following its economic reforms beginning in the late 1970s (Li, 1998). Lippit (2018) notes that China’s economic

development has had the fastest growth worldwide over the previous several decades. As one of the world’s fastest-growing economies, China had the largest annual GDP growth from both 1980-90

and 1990-99 (World Bank, 2001). Moreover, China even surpassed Japan in 2010 to have the second highest GDP worldwide, second only to the United States (World Bank, 2022). As an island with

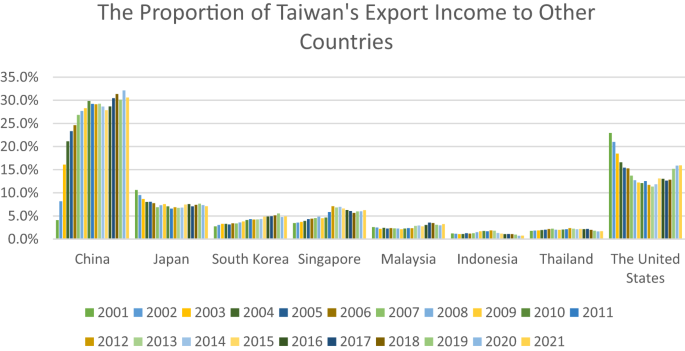

limited natural resources and high population density, Taiwan has established its place in the world economy through exports; Fig. 1 shows the proportion of Taiwan’s exports to other

countries. Although the USA and Japan ranked first and second as recipients of Taiwan’s exports in 2001, China surpassed Japan in 2003, and in 2004, it surpassed the USA in this respect.

Furthermore, since 2004, China’s proportion has exceeded 20%, and it has not dropped below 30% since 2017. China’s status as Taiwan’s largest export country may be due to several factors.

First, Taiwan promulgated the “Noninterference Principle of Indirect Exports to the Mainland” in 1985 as its first response to China’s request for cross-strait trade. Second, the

“Cross-Straits Economic Cooperation Framework (ECFA)” agreement was signed by Taiwan and China in 2010. Third, Taiwan is geographically close to China and is culturally similar. Taiwan’s

export orientation can be easily affected by domestic and foreign economic forces. The exchange rate is regarded as the decisive link between a country’s internal economy and the

international economy (Williamson, 2009). It is also an important factor for an export economy since the cost of exports fluctuate according to the exchange rate. Fluctuations in exchange

rates determine the relative prices of domestic and foreign commodities, as well as the extent to which external sectors participate in international trade (Adeniran et al., 2014). Exchange

rates are affected by both international trade and the current economic environment—most notably economic openness (Canales-Kriljenko & Habermeier, 2004); with greater economic

development, the environment approaches an open economy. With an open economy, the domestic economy is closely linked with the international economy and international trade. According to

international trade exchanges, the amount of the country’s export trade currency fluctuates with exchange rates and economic changes. In addition to exchange rate fluctuations, current

economic conditions also influence Taiwan’s export economy, and trends and fluctuations of the economy can be reflected by various indicators. Of these, the industrial production index (IPI)

can both indicate the current economic situation and reflect the speed of industrial development to reflect overall prosperity (Feng and Huang, 2020). The IPI is an index that covers

production in mining, manufacturing and public utilities (electricity, gas and water) but excludes construction (OECD, 1987). It measures the relative change in industrial production volume

between a certain timeFootnote 1 and a base periodFootnote 2 (Department of Statistics, 2022). It represents both a country’s industrial development conditions and the alignment of its

economy. Changes in Taiwan’s IPI follow the same trends as its exports to China (National Statistics, R.O.C. (Taiwan), 2022). Figure 2 shows the relationship between Taiwan’s export trade

returns with China, the currency exchange rate of RMB to NTD, and Taiwan’s IPI. Exchange rates can lead to large fluctuations in the industrial and manufacturing sectors (Lotfalipour et al.,

2013). Changes in exchange rates also affect industrial development, and these impacts will eventually appear in Taiwan’s export trade. Consequently, the currency exchange rate of RMB to

NTD and Taiwan’s IPI have a relationship in which a slight change in one aspect may substantially affect the situation as a whole. Therefore, this research focuses on the currency exchange

rate of RMB to NTD, adding in the IPI of Taiwan as a coincident economic index, to examine changes in export income from China, thereby investigating the relevant changes between Taiwan’s

IPI and export income from China. Through this research, the contributions of the study can understand how Taiwan’s export value to the mainland changes when the exchange rate of the RMB

against the New Taiwan Dollar fluctuates either above or below the critical value and when the IPI change value of Taiwan’’s economic indicator fluctuates. Taiwan is an export-oriented

country, and mainland China is Taiwan’s largest trading partner; thus, this research can provide accurate and complete trade information for domestic exporters or government units.

LITERATURE REVIEW RELATIONSHIP AMONG ECONOMY, EXCHANGE RATE AND EXPORTS As the coincident index of the economy, the IPI indicates the current economic situation and changes in the national

economy. Liao and Chen (2020) examine whether the IPI of a country that has trade relations with China affects the export income from China to that country. Adopting the fixed effect model

of the panel regression and the monthly data from February 2015 to September 2018, they find a positive important correlation between the IPI of China’s trading partners and China’s export

income. Specifically, a higher IPI of a country is correlated with a better ability of that county to purchase China’s products and greater income from exports from China to that country.

For Nordic countries, Hatemi and Irandoust (2000) evaluate the relationship between export income growth and economic growth using both Johansen’s technique and Granger causality tests and

data from the period of 1975 to 1996. The results imply a long-run causality relationship between growth export income and economic growth in Iceland. For Denmark, a one-way causality that

runs from economic growth to export income growth is found. Other countries, such as Finland, Norway and Sweden, demonstrate bidirectional causality. Afxentiou and Serletis (1991) test the

causal relationship between export income and the economy from 1950 to 1985 in 16 developed countries. By first testing the export income and the national economic situation for

cointegration and then using Granger tests, the results show that in Iceland, Norway, and the Netherlands, there is no cointegration between the two variables. However, a bidirectional

causality is found for the USA, and a one-way causal relationship is found to extend from export income to the economic situations in Norway, Canada, and Japan. To investigate the

relationship between the exchange rate and exports, Ngouhouo and Makolle (2013) study the factors that determined Cameroon’s export trade from 1970 to 2008. The results from empirical

analysis of the two-stage least-squares regression indicate that the exchange rate is one of the main determinants for exports from Cameroon. Having a negative coefficient indicates that

while there is an appreciation in the exchange rate of Cameroon, the exporting of Cameroon will be affected and lead to a drop. In contrast, when the exchange rate depreciates, the export

volume from Cameroon will increase. Arize et al. (2000) empirically examine the quarterly influence of real exchange rate volatility on export flows in 13 less developed countries (LDCs)

from 1973 to 1996 employing the error-correction technique. The study shows that the outcomes of increased REER volatility, similar to exchange rate uncertainty, will greatly reduce both

short-run and long-run export demand for each of the LDCs. Sharma (2000) uses the simultaneous equation framework to obtain factors that determine the performance of India’s exports,

applying annual data ranging from 1970 through 1998. The study implies that a real appreciation of the rupee has adverse impacts on exports in India, such that export demand would decline by

3.46% when the rupee appreciates by 10%. DYNAMIC MODEL Granger and Teräsvirta (1993) point out that because most macroeconomic variables have dynamic tendencies, if heterogeneity exists

between variables during the empirical modelling process, specification errors will occur during the course of estimation employing a conventional linear model, and bias will consequently

occur in estimation results. To resolve this problem and achieve more precise empirical conclusions, in recent years, a growing number of scholars have employed dynamic empirical models when

a model’s variables have a heterogeneous structure. The type and characteristics of dynamic models most commonly seen in the empirical literature include TAR models (Tong, 1978), which

constitute nonlinear regime-switching models. However, it is difficult to capture the true state of transition variations in the models during empirical research because the transition

process of this model is radical and discrete. Consequently, this type of model often cannot completely and correctly capture the transition processes of low-frequency data. The STAR model

(Chan and Tong, 1986) is composed of 2 nonlinear autoregressions linked by a transition function, and the transition process permits the variables to move between 2 different states; this

ensures that the smooth transition process is determined by the value of the lagged transition variable. However, this model is not suitable for models with a cross-sectional data structure.

The chief characteristic of the PTR model proposed by Hansen (1999) is the use of a time-varying threshold variable to divide the panel data into several different intervals, so that when

the observed value data are near the transition threshold, a jump will occur. This phenomenon is rarely seen in the real world, however. After changing the jump transition in this PTR model

to a smooth transition, González, Teräsvirta and van Dijk (2005) propose the PSTR model concept and add a transition speed parameter to their model. This transition speed parameter is used

to describe the model’s smooth transition phenomenon in the vicinity of the threshold value and ensures that the transition is not a simple jump. Furthermore, the transition variable

threshold value is estimated using quantitative methods and not specified artificially. This objective estimation approach can avoid bias in the estimated model extremes due to researchers’

subjective preconceptions. In view of the features and advantages of PSTR models, a growing number of scholars have recently adopted models of this type in their research (Béreau et al.

2012; Nikolaos and Minoas, 2019). The PSTR model captures data heterogeneity and has the advantages of accurately describing the model’s individual and time effects. This type of model can

also avoid the common problem of collinearity in linear structural models. Furthermore, this model can provide useful information to enhance the model’s estimation effectiveness when

researchers are studying situations with long dependent variable lag periods. This paper seeks to investigate the dynamic effect of trading between China and Taiwan under exchange rate

fluctuations, and the model’s variable data have time series characteristics. Applying the PSTR model, Heidari et al. (2014) test the relationship between agricultural raw material exports

and economic growth. According to data from the Developing Eight countries for 1996 to 2011, there were two regimes that gave a threshold at -0.971. In the first regime, the exports of

agricultural raw material had a major negative impact on economic growth. Second, there was a positive impact between agricultural raw material exports and economic growth. Chiu and Sun

(2016) test for the relation between the trade balance and the real exchange rate using the PSTR model from 1975 to 2010 in 76 countries, separating countries into high-income and low-income

groups. Both subsets show similar results, suggesting that a country’s trade balance can be improved by the depreciation of the country’s currency. Béreau et al. (2012) investigate the link

between real exchange rate misalignments and economic growth in a large set of countries, both developing and advanced. With a yearly sample period from 1980 through 2007 and the PSTR

model, they discover that real exchange rate misalignments affect economic growth differently based on the size and sign, i.e., whether the real exchange rate misalignments are overvalued or

undervalued. Overvalued real exchange rate misalignment can reduce economic growth, whereas it can be increased when the real exchange rate misalignment is undervalued. Undervaluation for

the misalignment of the exchange rate may push the exchange rate towards a level that both promotes economic growth and encourages exports. The above studies show that research findings

using the PSTR model can be more specific. For example, when a variable is above or below a certain threshold, the reaction of another variable can be seen. In addition, nearly all of the

abovementioned studies show a relationship between exports, the economy and the exchange rate, although there are only a few studies that focus on the relationship between the three

variables applying the PSTR model. Therefore, this study uses the PSTR model to verify the dynamic relationship among Taiwan’s export income from China, Taiwan’s IPI, and the currency

exchange rate of RMB to NTD. DATA AND METHODOLOGY RESEARCH DATA The data used of this research was collected monthly from January 2001 to February 2022; Table 1 lists information on the

variables, including their name, code, measurement, and source. The dependent variable indicates Taiwan’s export income with China. For the many types of exports, to better analyse all

export data, Taiwan has classified products according to the United Nations Standard International Trade Classification (SITC, fourth edition). For data consistency, the export income is

presented as a rate of change. The formula for the rate of change of export income of Taiwan from China can be written as follows: $$\Delta ETM_{i,t} = \frac{{\left( {ETM_{i,t} - ETM_{i,t -

1}} \right)}}{{ETMi,_{t - 1}}} \times 100{{{\mathrm{\% }}}}$$ (1) where the export income of Taiwan from China is defined as _ETM_, with _i_ representing the export category and _t_ the time

period. Thus, \(ETM_{i,t}\) refers to the export income of each category \(\left( i \right)\) in period \(\left( t \right)\), and \(ETM_{i,t - 1}\) is the export income for each category

\(\left( i \right)\) in the prior period \(\left( {t - 1} \right)\) of period \(\left( t \right)\). The independent variable is the IPI of Taiwan. Additionally, for data consistency, the IPI

of Taiwan is also presented as a rate of change, calculated as follows: $$\Delta IPI_t = \frac{{\left( {IPI_t - IPI_{t - 1}} \right)}}{{IPI_{t - 1}}} \times 100{{{\mathrm{\% }}}}$$ (2)

where \(IPI_t\) denotes Taiwan’s IPI in period \(\left( t \right)\), and \(IPI_{t - 1}\) is Taiwan’s IPI in the prior period \(\left( {t - 1} \right)\) of period \(\left( t \right)\). The

transfer variable of this study is the currency exchange rate of RMB to NTD; since the currency exchange rate itself is already consistent with the above data, no further calculation is

needed. LINEAR MODEL To examine the relationship between Taiwan’s export income from China and the IPI of Taiwan, along with the threshold effect of the currency exchange rate of RMB to NTD,

the first step is to specify the linear relationship between the two variables, namely, Taiwan’s export income with China and Taiwan’s IPI, with a linear model. This helps analyse the

experimental data and provides biased estimated results that can be compared later with the results by using the PSTR model. The following formula presents the empirical linear model:

$$\Delta ETM_{i.t} = \alpha _0 + \beta _1\Delta IPI_t + \varepsilon _{i,t}$$ (3) where \(i = 1,2, \ldots ,\) \(N\) denotes the categories of exporting. \(t = 1,2, \ldots\), \(T\) denotes

time. \(\Delta ETM_{i,t}\) denotes the categories \(\left( i \right)\) of Taiwan’s monthly export income with China in period \(\left( t \right)\). \(\Delta IPI_t\) denotes the industrial

production index (IPI) of Taiwan in period \(\left( t \right)\), and \(\varepsilon _{i,t}\) is a residual term. PSTR MODEL As mentioned in Chapter 2, the PSTR model, proposed by González et

al. (2005) and Fok et al. (2005), is an extension of the PTR model that can provide smoothly varying cross-sectional correlations, cross-sectional heterogeneity, and temporal instabilities

of effects, so the nonlinear problem of this research can be resolved. Moreover, the PSTR model can examine threshold effects since when the transfer variable is above or below a threshold,

different responses of the dependent variable and the independent variable can be seen. Thus, this research utilizes the PSTR model to test the nonlinearity, and it can be written as

follows: $$\Delta ETM_{i,t} = \alpha _i + \beta _0X_{i,t} + \beta _1X_{i,t}G\left( {q_{i,t};\gamma ,c} \right) + \mu _{i,t}$$ (4) where \(i = 1,2, \ldots\), \(N\) denotes the categories of

exporting. \(t = 1,2, \ldots\), \(T\) denotes time. \(\Delta ETM_{i,t}\) denotes the categories \(\left( i \right)\) of Taiwan’s monthly export income with China in period \(\left( t

\right)\). A vector of exogenous explanatory variables is written as \(X_{i,t}\), for example, \(X_{i,t} = \left( {\Delta IPI_t} \right)\); with the bounded value from 0 to 1, the transition

function is defined as \(G( {q_{i,t};\gamma ,c})\). Specifically, \(q_{i,t}\) is the transition variable, and \(\gamma\) and \(c\) are the transition parameter and transition threshold

value, respectively. The optimal lagged transition variable is determined by the minimum Akaike information criterion (AIC) and Bayesian information criterion (BIC). \(\mu _{i,t}\) is a

residual term. The following function shows the written form of the transition variable: $$G\left( {q_{i,t};\gamma ,c} \right) = \left[ {1 + exp\left[ { - \gamma \mathop {\prod }\limits_{j =

1}^m \left( {q_{i,t} - c_j} \right)} \right]} \right]^{ - 1}$$ (5) where \(\gamma \,>\, 0\) and \(C_1 \le C_2 \le \ldots \le C_m\). When \(m = 1\) and \(\gamma \to \infty\), the PSTR

model reduces to a panel transition regression model. For the result of regime switching, González et al. (2005) only considered the case of \(m = 1\) and the case of \(m = 2\) to capture

nonlinearities. The PSTR model can be written as the following function: $$\Delta ETM_{i,t} = \alpha _i + \beta _0X_{i,t} + \mathop {\sum }\limits_{j = 1}^\gamma \beta _jX_{i,t}G_j\left(

{q_{i,t};\gamma _j,c_j} \right) + \mu _{i,t}$$ (6) where \(j = 1,2, \ldots\), \(r\) denotes the number of transition functions, and \(\left( {r + 1} \right)\) is the number of regimes.

ESTIMATION AND SPECIFICATION TESTS According to Yang et al. (2019), three steps are needed for estimating Eqs. (4) and (6). First, with the null hypothesis shown below, testing whether

nonlinearity exists is necessary. \(H_0\): The transition effects are shown in the linear model. \(H_1\): There is at least one threshold value \(\left( {r = 1} \right)\) of the PSTR model.

As long as the null hypothesis of linearity is not rejected, this indicates that transition effects do exist. Then, the transition variables are selected and determined. Finally, selecting

the currency exchange rate of RMB to NTD as the transition variable, Eqs. (4) and (6) are constructed. Du and Zhu (2001) argue that the influence of the exchange rate on exports is active.

Additionally, exchange rate volatility exerts a significant influence on exports (Verheyen, 2012; Hooy, Law, and Chan, 2015.). Hence, the exchange rate can be a policy variable that

influences economic growth (Wong, 2013). In sum, the exchange rate influences the marginal effects of IPI on the trading between China and Taiwan. This paper uses the volatility rate of the

exchange rate to construct the transition variable in Eqs. (4) and (6). The linearity of Eq. (6) is examined by the following equation: $$\Delta ETM_{i,t} = \beta _i + \beta _1\Delta IPI_t +

\beta _1^\prime \Delta IPI_tq_{t - d} + \eta _{i,t}$$ (7) where \(d = 0,1, \ldots ,5\) to allow for the monthly currency exchange rate of RMB to NTD. The linearity test is performed to

conduct the testing of \(H_0:\beta _1^\prime = 0.\) However, if the null hypothesis of linearity is rejected, a single threshold model or a double threshold model may exist; thus, another

test is needed. The testing procedure is continued until the hypothesis without an additional threshold is not rejected. Finally, removing the individual-specific means and applying the

nonlinear least squares method is the final step. Here, \(PSSR_0\) indicates the panel sum of squared residuals under the null hypothesis, such as the linear panel model with individual

effects, and \(PSSR_1\) indicates the panel sum of squared residuals under the alternative, for example, the PSTR model with two regimes. The corresponding LM statistic is shown as follows:

$$LM_F = \left[ {\left( {PSSR_0 - PSSR_1} \right)/K} \right]/\left[ {PSSR_0/\left( {TN - N - K} \right)} \right]$$ (8) where \(K\) is the number of explanatory variables. Under the null

hypothesis, the LM statistic has an asymptotic \(X^2\left( K \right)\) distribution. EMPIRICAL ANALYSIS AND FINDINGS DESCRIPTIVE STATISTICS This study uses three variables, namely, \(\Delta

ETM_{i,t},\Delta IPI_t,and\;EX_t\). \(\Delta ETM_{i,t}\) refers to the monthly export income of Taiwan from China from category \(\left( i \right)\) during period \(\left( t \right)\).

\(\Delta IPI_t\) indicates the monthly industrial production index (IPI) of Taiwan at time \(\left( t \right)\). \(EX_t\) is the monthly currency exchange rate of RMB to NTD in period

\(\left( t \right)\). Based on 4554 total observations for each variable from January 2001 to February 2022 for Taiwan’s export income from China, the IPI of Taiwan, and the currency

exchange rate of RMB to NTD, the maximum value, minimum value, mean value, and the standard deviation value of the variables are shown in Table 2. Table 2 shows that of all the variables,

\(\Delta ETM_{i,t}\) has the largest range from the maximum value (52.33333) to the minimum value (−1.00000). Furthermore, the standard deviation of \(\Delta ETM_{i,t}\) (1.163191) is larger

than that of the other variables. A larger standard deviation indicates a wider distribution of data and a larger difference between most of the values and the mean value. On the other

hand, a smaller standard deviation indicates a narrower data distribution and smaller differences between most of the values and the mean value, such as the variable \(\Delta IPI_t\).

Although \(\Delta IPI_t\) has a larger range from the maximum (0.313120) to minimum (−0.201586), compared to \(EX_t\), the standard deviation of \(\Delta IPI_t\) (0.085280) is still smaller

than that of \(EX_t\) (0.330037). This indicates that most of the data for \(EX_t\) have larger differences from the mean values. HAUSMAN TESTS It is necessary to first determine a model to

test correlations between the variables. This study applies the Hausman test to decide whether it is best to use the fixed effect or the random effect. There are two ways to judge the

Hausman test, and the first is whether the study accepts \(H_0\) or \(H_1\). \(H_0\): Selecting the random effect. \(H_1\): Selecting the fixed effect. The second judgement method is to

determine whether the p value of the test is above \(\left( { > 0.05} \right)\) or below 0.05 \(\left( { < 0.05} \right)\). In conclusion, if a study accepts that \(H_0\) or the p

value is \(> 0.05\), then it is best to use the random effect. However, if a study accepts \(H_1\) or the p value is shown to be \(< 0.05\), it is best to use the fixed effect model

(Zulfikar, 2018). The test results of this research are shown in Table 3. In the table, next to the value 9.229519, three *** are shown, meaning that the p value is \(< 0.01\), rejecting

the null hypothesis. Thus, it is best to use the fixed effect for further analysis. NONLINEAR UNIT ROOT TESTS To test whether the variables are stationary, this research utilizes the unit

root test of structural breaks. This method can determine whether the nonlinear structural sequence can still reach a stationary state during the transformation over time. Table 4 shows the

results for each variable from the nonlinear unit root test. The table indicates that all three variables are strongly significant, meaning that in this sequence structure, a nonlinear

structural transformation does exist, and as time passes, the variables will eventually be stationary. Figures 3–5 show the test of the Dicky-Fuller autoregressive coefficients for \(\Delta

ETM_{i,t}\), \(\Delta IPI_t\), and \(EX_t\), respectively. Then, the Granger causality test is applied, running from both directions, \(\Delta IPI_t\) to \(\Delta ETM_{i,t}\) and \(\Delta

ETM_{i,t}\) to \(\Delta IPI_t\), to discover causality between the two variables. Table 5 shows that bidirectional causality exists between the two variables, namely, \(\Delta IPI_t\) and

\(\Delta ETM_{i,t}\). More specifically, the correlations between the dependent variable \(\Delta ETM_{i,t}\) and the independent variable \(\Delta IPI_t\), either running from \(\Delta

IPI_t\) to \(\Delta ETM_{i,t}\) or running from \(\Delta ETM_{i,t}\) to \(\Delta IPI_t\), are causal relationships. LINEAR TESTS Since the results of the nonlinear unit root tests show that

all the variables will be stationary, the next step is to test whether the model has a nonlinear relationship between Taiwan’s export income with China and the IPI of Taiwan. To discover the

relationship between Taiwan’s export income with China and the IPI of Taiwan, the first step is to determine if the relationship is nonlinear or linear; by testing the following hypothesis,

the relationship between the two variables can be calculated. \(H_0\): Linear model. \(H_1\): PSTR model with at least one threshold variable \(\left( {r = 1} \right)\). If the test results

reject the null hypothesis of linearity, then the subsequent step is to test the null hypothesis of a single threshold model against a double threshold model. Using the model described in

3.3.1., i.e., Eq. (3), the outcomes are shown in Table 6. This test is divided into two cases; the first is that the location parameter is one \(\left( {m = 1} \right)\), while the second is

that there are two location parameters \(\left( {m = 2} \right)\). The second case increases the reliability since it confirms the results from the first. This table shows that in the first

case, i.e., where the location parameter is one \(\left( {m = 1} \right)\), the results of each test, namely, Wald, Fisher, and LRT, reject the null hypothesis of linearity at a confidence

level of at least 90%. When the location parameter is two \(\left( {m = 2} \right)\), the results also show the rejection of the null hypothesis of linearity, this time at a significance

level of 95%, for each of the tests. Based on the results and estimation, the relationship between Taiwan’s export income from China and the IPI of Taiwan is clearly nonlinear. Therefore,

the following study should be based on nonlinear models, and the minimum principle of AIC or BIC reveals that the transfer function conforms to the PSTR model. Because of the nonlinear

relationship between Taiwan’s export income with China and the IPI of Taiwan, further analysis with the optimal number of threshold regime tests determines the optimal number of threshold

variables, with the following hypotheses: \(H_0\): PSTR model with one threshold variable \(\left( {r = 1} \right)\). \(H_1\): PSTR model with at least two threshold variables \(\left( {r

\ge 2} \right)\). This test is also divided into two cases, namely, either one location parameter \(\left( {m = 1} \right)\) or two \(\left( {m = 2} \right)\); the results are shown in Table

7. The table shows that for both one and two location parameters, none of the tests, namely, Wald, Fisher, and LRT, reject the null hypothesis, indicating that one is the optimal number for

the transition function. EMPIRICAL RESULTS After the nonlinear unit root test, the linearity test, and the optimal number of threshold regime test, this study applies the PSTR model. Table

8 presents the results of both the PSTR model and the traditional linear model, with both results shown in the same table for ease of comparison. In Table 8, the results show that in the

left column of the PSTR model, the threshold value \(c\) and the transition parameter \(\gamma\) are 4.1732 and \(5.9615e + 003\), respectively. Given the threshold value of 4.1732, which

reflects the rate of change for the dependent variable, Taiwan’s export income with China (\(\Delta ETM_{i,t}\)) will change according to whether the transfer variable for the currency

exchange rate of RMB to NTD, as well as the code \(EX_t\), is above or below that value. In view of the model of Taiwan’s export income with China, the current period of Taiwan’s IPI

(\(\Delta IPI_t\)) influences the current period of Taiwan’s export income with China (\(\Delta ETM_{i,t}\)). When the current period of the currency exchange rate of RMB to NTD (\(EX_t\))

is the transfer variable, the threshold value is 4.1732, which suggests that the smooth transition effect demonstrated by it is fluctuating. The effect of Taiwan’s IPI (\(\Delta IPI_t\)) on

Taiwan’s export income with China (\(\Delta ETM_{i,t}\)) depends on the level of the current period of the transfer variable, which is the currency exchange rate of RMB to NTD (\(EX_t\)).

The smooth transition effect of the model of the IPI of Taiwan can be written as \(\left( {0.7451 + 1.3150} \right)^\ast F\left( {EX_t;5.9615e + 003,4.1732} \right)\), which indicates that

for the two extreme cases presented by the model where the effect is 0 and 100%, the values are 1.3421 and 0.4854, respectively. In other words, under the linear effect, the marginal effect

caused by the fluctuation of the IPI of Taiwan (\(\Delta IPI_t\)) is 4.1732. With the change of time, regardless of whether the currency exchange rate of RMB to NTD (\(EX_t\)) is in the

interval below the threshold value or above the threshold value, both cases will cause the marginal effect of Taiwan’s export income with China (\(\Delta ETM_{i,t}\)) to be positive;

however, this is demonstrated as changing from strong positive to weak positive. That is, as the IPI of Taiwan (\(\Delta IPI_t\)) is accompanied by the influence of the currency exchange

rate of RMB to NTD (\(EX_t\)), the income of Taiwan’s export income with China (\(\Delta ETM_{i,t}\)) decreases. If this is interpreted in terms of the actual market, when the market is

depressed, even though the currency exchange rate of RMB to NTD (\(EX_t\)) is appreciating, it still contributes to an increase in the income for the current period of Taiwan’s export income

with China (\(\Delta ETM_{i,t}\)). When the market is expanding and the currency exchange rate of RMB to NTD (\(EX_t\)) is below the threshold value, an increase of one unit in the IPI of

Taiwan (\(\Delta IPI_t\)) will greatly enhance Taiwan’s export income from China (\(\Delta ETM_{i,t}\)). In sum, Taiwan’s export income from China (\(\Delta ETM_{i,t}\)) leads to income

effects of varying degrees of smooth transition effect, regardless of whether the currency exchange rate of RMB to NTD (\(EX_t\)) is above or below the threshold value. This means that there

is a trade surplus in bilateral trade between Taiwan and China. As mentioned in the previous sections, the PSTR model can both resolve the nonlinear problem and provide more precise

results, which indicates that the relationship between Taiwan’s export income and the IPI of Taiwan is nonlinear; thus, in the two extreme regimes, there will be different effects. The

threshold value \(c\) and the transition parameter \(\gamma\) are 4.1732 and \(5.9615e + 003\), respectively. The coefficient variable is \(\beta _1\) 0.7451. The following equation can

explain the relationship between Taiwan’s export income with China and the IPI of Taiwan: $$\Delta ETM_{i,t} = \alpha _i + \beta _0\Delta IPI_t + 0.7451\Delta IPI_tG\left( {EX_t;5.9615e +

003,4.1732} \right)$$ (9) where \(\Delta ETM_{i,t}\) refers to the categories \(\left( i \right)\) of Taiwan’s monthly export income with China in period \(\left( t \right)\). \(EX_t\)

refers to the monthly currency exchange rate of RMB to NTD in period \(\left( t \right)\). \(\Delta IPI_t\) refers to the industrial production index (IPI) of Taiwan in period \(\left( t

\right)\). CONCLUSION According to the results in the above chapters, the final step is to discuss what has already been found in the previous chapters and the implications. Chapter Five

thus contains such a discussion and implications for future research. RESULTS DISCUSSION These data span from January 2001 to February 2022, and the PSTR model with the threshold variable of

the currency exchange rate of RMB to NTD (\(EX_t\)) examines the relationship between Taiwan’s export income from China (\(\Delta ETM_{i,t}\)) and the IPI of Taiwan (\(\Delta IPI_t\)).

Details of the empirical results are discussed below. The results from the linearity test and the optimal number of threshold regime tests show that there is one threshold value, namely,

4.1732, in the relationship between Taiwan’s export income with China (\(\Delta ETM_{i,t}\)) and the IPI of Taiwan (\(\Delta IPI_t\)). Due to the threshold effect, Taiwan’s export income

with China (\(\Delta ETM_{i,t}\)) and the IPI of Taiwan (\(\Delta IPI_t\)) will be different when the currency exchange rate of RMB to NTD (\(EX_t\)) is below or above this threshold value.

The nonlinear model has two extreme cases, that is, before transition \({{{\mathrm{G}}}}\left( {\Delta IPI_t;0.7451} \right) = 0\) and after transition \({{{\mathrm{G}}}}\left( {\Delta

IPI_t;1.3150} \right) = 1\), which cause the marginal effect to be below (1.3421, 4.1732) or above (0.4854, 4.1732) the threshold value. It is clear that the marginal effect estimated by the

nonlinear model below the threshold value is obviously higher than that obtained above the threshold value. In conclusion, the effect of Taiwan’s IPI (\(\Delta IPI_t\)) on Taiwan’s export

income from China (\(\Delta ETM_{i,t}\)) is nonlinear; furthermore, it is clear that when the currency exchange rate of RMB to NTD (\(EX_t\)) is below or above the threshold value, Taiwan’s

export income with China (\(\Delta ETM_{i,t}\)) will increase as the IPI of Taiwan (\(\Delta IPI_t\)) increases, only with different degrees of increase. Taiwan’s export income from China

(\(\Delta ETM_{i,t}\)) increases more when the currency exchange rate of RMB to NTD (\(EX_t\)) is below the threshold value than when it is above the threshold. From an economic point of

view, when the currency exchange rate of RMB to NTD (\(EX_t\)) is below the threshold, the NTD appreciates. When the currency exchange rate of RMB to NTD (\(EX_t\)) is above the threshold

value, the NTD depreciates. The results discussed herein show that when the NTD is appreciating, which also means that the market is expanding, as the IPI of Taiwan (\(\Delta IPI_t\))

increases by one unit, Taiwan’s export income with China (\(\Delta ETM_{i,t}\)) will increase more than when the NTD is declining. This shows that when the market expands and the currency is

appreciating, Taiwan’s exports will have better performance. CONCLUDING REMARKS Under globalization, trade exchanges between countries are critical, especially for island countries lacking

natural resources, such as Taiwan; thus, changes in currency exchange rates are an extremely important factor in trade because export income is influenced by changes in the currency exchange

rate. Wade (1990) mentions that the basic economic policy of Taiwan is that the government is committed to strengthening the power of the market, and the expansion of exports of Taiwan’s

industries will help the industry achieve economies of scale, thereby increasing its productivity (Chuang, 1993). However, changes in export income are also affected by a country’s economic

development; thus, this research includes Taiwan’s IPI in its investigations. The results show that the economy affects changes in the exchange rate, while the exchange rate plays a very

important role in the exchange rate difference in the amount of exports. The exchange rate can be a policy variable affecting economic growth. Real exchange rate misalignments should be

avoided so that economic resources are allocated according to needs. This study focuses on the three variables and the empirical results show there is causality between the export income and

the IPI.Moreover, a threshold value exists, indicating that the relationship between the export income and the IPI is nonlinear. On the basis of the threshold effect, there will be

different changes in the export income. To be more precise, when the currency exchange rate is below the threshold value, a one-unit increase in the IPI, will cause the export income to

increase by 1.3421 unit. On the other hand, above the threshold value, export income will increase by 0.4854 unit as the IPI increases one unit. Using the currency exchange rate of RMB to

NTD (\(EX_t\)) to show the results, when NTD depreciates, it not only immediately reflects the decline in Taiwan’s export income with China (\(\Delta ETM_{i,t}\)), but also immediately

reflects economic performance. Just as when the currency exchange rate of RMB to NTD (\(EX_t\)) is above the threshold value, the amount of the trade surplus falls, indicating that, even

though appreciation or depreciation of the currency changes Taiwan’s export income from China (\(\Delta ETM_{i,t}\)), there is still a surplus. Three conclusions can be drawn from this

study, first, the effect of the IPI of Taiwan (\(\Delta IPI_t\)) on Taiwan’s export income with China (\(\Delta ETM_{i,t}\)) is nonlinear, and according to the currency exchange rate of RMB

to NTD (\(EX_t\)) varies within threshold intervals and changes through time. This result differs from the empirical results confirmed by the traditional linear models. Second, during the

transition of the IPI of Taiwan (\(\Delta IPI_t\)) at the currency exchange rate of RMB to NTD (\(EX_t\)), the effect on Taiwan’s export income with China (\(\Delta ETM_{i,t}\)) is greater.

Finally, when the current period of the currency exchange rate of RMB to NTD (\(EX_t\)) is below the threshold value, the income of Taiwan’s export with China (\(\Delta ETM_{i,t}\)) in the

current period is higher than when the currency exchange rate of RMB to NTD (\(EX_t\)) in the current period is above the threshold value. Investigation results show the relationship between

export income and the IPI, which is an advance on previous research. DATA AVAILABILITY The datasets are available by contacting the corresponding author on reasonable request. NOTES *

Statistics before the 23rd of each month (Department of Statistic, 2022). * The period of time during which data is collected to be used as the basis for an index or other ratio, frequently

once year, thought it may be as short as a day or as long as an average over several years (Dodge, 2010). Taking the 2016 Republic of China (ROC) era as the base period, the base period is

changed every five years (Department of Statistics, 2022). REFERENCES * Adeniran JO, Yusuf SA, Adeyemi OA (2014). The impact of exchange rate fluctuation on the Nigerian Economic Growth: An

Empirical investigation. Int J Acad Res Bus Soc Sci 4(8). https://doi.org/10.6007/ijarbss/v4-i8/1091 * Afxentiou PC, Serletis A (1991) Exports and GNP causality in the industrial countries:

1950–1985. Kyklos 44(2):167–179. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6435.1991.tb02095.x Article Google Scholar * Arize AC, Osang T, Slottje DJ (2000) Exchange-rate volatility and foreign

trade: Evidence from thirteen LDC’s. J Bus Econ Stat 18(1):10. https://doi.org/10.2307/1392132 Article Google Scholar * Béreau S, Villavicencio AL, Mignon V (2012) Currency misalignments

and growth: A new look using nonlinear panel data methods. Appl Econ 44(27):3503–3511. https://doi.org/10.1080/00036846.2011.577022 Article Google Scholar * Canales-Kriljenko JI,

Habermeier K (2004). Structural factors affecting exchange rate volatility: A cross-section study. SSRN Electr J. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.878972 * Chan KS, Tong H (1986) On estimating

thresholds in autoregressive models. J Time Series Anal 7:179–190. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9892.1986.tb00501.x Article MathSciNet MATH Google Scholar * Chiu YB, Sun CHD (2016) The

role of savings rate in exchange rate and trade imbalance Nexus: Cross-countries evidence. Econ Model 52:1017–1025. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econmod.2015.10.040 Article Google Scholar *

Chuang Y-C (1993). Learning by Doing, Technology Gap, and Growth, Ph. D. Dissertation, University of Chicago * Department of Statistic. (2022). Dynamic Survey of Industrial Production, Sales

and Inventory. Retrieved May 16, 2022, from https://www.moea.gov.tw/MNS/dos/content/Content.aspx?menu_id=6820 * Dodge Y (2010). _The Oxford Dictionary of Statistical terms_. Oxford

University Press * Du H, Zhu Z (2001) The effect of exchange-rate risk on exports: Some additional empirical evidence. J Econ Stud 28(2):106–121 Article Google Scholar * Feng KW, Huang CH

(2020). _Hui Lu Bo Dong Dui Tai Wan-Mei Guo Mao Yi Jian Ying Xiang: Yi Chan Ye Mao Yi Zi Liao Fen Xi_ (thesis). Guo li qing hua da xue, Xin zhu shi * Fok D, Van Dijk D, Franses PH (2005) A

multi-level panel star model for US manufacturing sectors. J Appl Econom 20(6):811–827. https://doi.org/10.1002/jae.822 Article MathSciNet Google Scholar * Ghartey EE (1993) Causal

relationship between exports and economic growth: Some empirical evidence in Taiwan, Japan and the US. Appl Econ 25(9):1145–1152. https://doi.org/10.1080/00036849300000175 Article Google

Scholar * González A, Terasvirta T, Dijk DV (2005). _Panel smooth transition regression models_ * Granger CWJ, Teräsvirta T (1993). Modelling non-linear economic relationships. Oxford

University Press. https://doi.org/10.1002/jae.3950090412 * Heidari H, Alinezhad R, Jahangirzadeh J (2014) An Investigation of Democracy and Economic Growth Nexus: A Case Study for D-8

Countries. Economic Growth and Development Research 4(15):60–41 Google Scholar * Hansen BE (1999) Threshold effects in non-dynamic panels: Estimation, testing, and inference. J Econom

93(2):345–368. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0304-4076(99)00025-1 Article MathSciNet MATH Google Scholar * Hatemi-J A, Irandoust M (2000) Export Performance and Economic Growth Causality: An

empirical analysis. Atlantic Econ J 28(4):412–426. https://doi.org/10.1007/bf02298394 Article Google Scholar * Hooy CW, Law SH, Chan TH (2015) The impact of the renminbi real exchange rate

on ASEAN disaggregated exports to China. Econ Model 47:253–259 Article Google Scholar * Jin JC, Shih YC (1995) Export-led growth and the four little dragons. J Int Trade Econ Dev

4(2):203–215. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638199500000017 Article Google Scholar * Li L (1998) The China miracle: Development strategy and economic reform. Cato J 18(1):147 Google Scholar *

Liao SE, Chen PF (2020). _The Impact of Renminbi Exchange Rate on Export-A Cross-Country Analysis_ (thesis). National Sun Yat-sen University, Kaohsiung * Lippit VD (2018). _The economic

development of China_ (Vol. 9). Routledge * Lotfalipour MR, Ashena M, Zabihi M (2013) Exchange rate impacts on investment of manufacturing sectors in Iran. Bus Econ Res 3(2):12.

https://doi.org/10.5296/ber.v3i2.3716 Article Google Scholar * Mascelluti E (2015). The extraordinary growth of the four Asian tigers * Nikolaos G, Minoas K (2019) Gold price and exchange

rates: A panel smooth transition regression model for the G7 countries. North Am J Econ Finance 49:27–46. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.najef.2019.03.018 Article Google Scholar * National

Statistics, Republic of China (Taiwan). (2022). Industrial Production Index. Retrieved May 16, 2022, from https://statdb.dgbas.gov.tw/pxweb/Dialog/Saveshow.asp * Ngouhouo I, Makolle AA

(2013) Analyzing the determinants of export trade in Cameroon (1970–2008). Mediterranean J Soc Sci 4(1):599 Google Scholar * OECD, EO (1987). Sources and methods * Schive C (1995)

Industrial policies in a maturing Taiwan economy. J Ind Stud 2(1):5–26. https://doi.org/10.1080/13662719500000002 Article Google Scholar * Sharma K (2000). Export Growth in India: Has FDI

played a role? _Working or Discussion Paper_. https://doi.org/10.22004/ag.econ.28372 * The World Bank Data. (2022). GDP (current US$) - China, United States, Japan. Retrieved May 16, 2022,

from https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.MKTP.CD?locations=CN-US-JP * The World Bank. (2001). World Development Report 2000/2001 * Tong H (1978). On a threshold model. In: Chen, C,

(ed.) Pattern Recognition and Signal Processing. NATO ASI Series E: Applied Sc. (29). Sijthoff & Noordhoff, Netherlands, 575-586. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-009-9941-1_24 * Verheyen

F (2012) Bilateral exports from euro zone countries to the US—Does exchange rate variability play a role? Int Rev Econ Finance 24:97–108 Article Google Scholar * Wade R (1990). Governing

the Market, Princeton: Princeton University Press * Williamson J (2009) Exchange rate economics. Open Econ Rev 20(1):123–146 Article Google Scholar * Wong HT (2013). Real exchange rate

misalignment and economic growth in Malaysia. J Econ Stud 298–313 * Yang TY, Thanh H, Yen CW (2019) Oil threshold value between oil price and production. Panoeconomicus 66(4):487–505.

https://doi.org/10.2298/pan161013009y Article Google Scholar * Zulfikar R (2018). Estimation model and selection method of panel data regression: An overview of common effect, fixed

effect, and random effect model. https://doi.org/10.31227/osf.io/9qe2b Download references AUTHOR INFORMATION AUTHORS AND AFFILIATIONS * Graduate Program of International Business

Communication, Department of Foreign Languages and Literature, National Ilan University No. 1, Section 1, Shennong Rd, Yilan City, Yilan County 260, Taiwan Tzu-Yi Yang & Chieh Liu *

Department of Aeronautical and Opto-Mechatronic Engineering, Vanung University, No.1 Vanung Rd. ChungLi, Taoyuan, 32061, Taiwan Yu-Tai Yang * Department of Industrial Engineering and

Management, Center for Artificial Intelligence & Data Science, Ming Chi University of Technology, No.84, Gungjuan Rd., Taishan Dist., New Taipei City, 24301, Taiwan Ssu-Han Chen Authors

* Tzu-Yi Yang View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Chieh Liu View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google

Scholar * Yu-Tai Yang View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Ssu-Han Chen View author publications You can also search for this author

inPubMed Google Scholar CORRESPONDING AUTHOR Correspondence to Yu-Tai Yang. ETHICS DECLARATIONS COMPETING INTERESTS The author declares no competing interests. ADDITIONAL INFORMATION

PUBLISHER’S NOTE Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. We confirmed all authors’ institutional (or personal)

email addresses are on their institutional website. RIGHTS AND PERMISSIONS OPEN ACCESS This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits

use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the

Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated

otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds

the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. Reprints and

permissions ABOUT THIS ARTICLE CITE THIS ARTICLE Yang, TY., Liu, C., Yang, YT. _et al._ The dynamic effect of trading between China and Taiwan under exchange rate fluctuations. _Humanit Soc

Sci Commun_ 10, 397 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-023-01903-8 Download citation * Received: 03 December 2022 * Accepted: 28 June 2023 * Published: 10 July 2023 * DOI:

https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-023-01903-8 SHARE THIS ARTICLE Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content: Get shareable link Sorry, a shareable link is not

currently available for this article. Copy to clipboard Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative