Refined high-content imaging-based phenotypic drug screening in zebrafish xenografts

- Select a language for the TTS:

- UK English Female

- UK English Male

- US English Female

- US English Male

- Australian Female

- Australian Male

- Language selected: (auto detect) - EN

Play all audios:

ABSTRACT Zebrafish xenotransplantation models are increasingly applied for phenotypic drug screening to identify small compounds for precision oncology. Larval zebrafish xenografts offer the

opportunity to perform drug screens at high-throughput in a complex in vivo environment. However, the full potential of the larval zebrafish xenograft model has not yet been realized and

several steps of the drug screening workflow still await automation to increase throughput. Here, we present a robust workflow for drug screening in zebrafish xenografts using high-content

imaging. We established embedding methods for high-content imaging of xenografts in 96-well format over consecutive days. In addition, we provide strategies for automated imaging and

analysis of zebrafish xenografts including automated tumor cell detection and tumor size analysis over time. We also compared commonly used injection sites and cell labeling dyes and show

specific site requirements for tumor cells from different entities. We demonstrate that our setup allows us to investigate proliferation and response to small compounds in several zebrafish

xenografts ranging from pediatric sarcomas and neuroblastoma to glioblastoma and leukemia. This fast and cost-efficient assay enables the quantification of anti-tumor efficacy of small

compounds in large cohorts of a vertebrate model system in vivo. Our assay may aid in prioritizing compounds or compound combinations for further preclinical and clinical investigations.

SIMILAR CONTENT BEING VIEWED BY OTHERS ZEBRAFISH XENOGRAFTS AS A FAST SCREENING PLATFORM FOR BEVACIZUMAB CANCER THERAPY Article Open access 10 June 2020 SINGLE-CELL IMAGING OF HUMAN CANCER

XENOGRAFTS USING ADULT IMMUNODEFICIENT ZEBRAFISH Article 21 August 2020 AUTOMATED MICROINJECTION FOR ZEBRAFISH XENOGRAFT MODELS Article Open access 23 April 2025 INTRODUCTION Cancer is the

second leading cause of death worldwide and remains a major global health challenge despite improvements in treatment1. Various strategies are pursued to develop novel small compounds with

anti-cancer activity. Most often a target-based approach is applied, where small compounds are designed to inhibit the function of a protein based on protein structure. Predicted anti-tumor

activity of such compounds is typically verified in cell culture assays, which are amenable to high-throughput drug screening. Subsequently, candidate molecules are tested in preclinical

animal models. Here, mouse xenograft models, in particular patient-derived xenografts are the current gold standard to evaluate compound efficacy on whole organism level2. However, mouse

xenografts are laborious, time-consuming and costly to establish, preventing their broad application in high-throughput drug screening. In recent years, the zebrafish (_Danio rerio_) tumor

cell xenotransplantation model has emerged as a complementary system to mouse xenografts3. Several groups demonstrated that larval zebrafish xenografts can be established with a variety of

cancer cell lines ranging from leukemia to solid tumors4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11. More recently, even patient-derived xenografts for colorectal cancer and non-small cell lung carcinoma were

generated in zebrafish and early data suggests that such zebrafish avatar models might be useful in predicting disease progression and in identifying patient-tailored treatments12,13. Major

advantages of the larval zebrafish xenograft model are the possibility to carry out a) live imaging e.g., of tumor cell proliferation and migration in the intact transparent vertebrate

organism, b) fast and cost-efficient drug screening and c) toxicity evaluation of compounds on whole organism level at early developmental stages14,15. Larval zebrafish xenografts are small

enough to fit into 96-well plates and compounds can be administered directly into the surrounding water. Such assays have been methodically improved and been increasingly used over the past

years4,11,16,17,18,19,20. Furthermore, this format offers the opportunity to perform phenotypic drug screening on zebrafish xenografts at high-throughput. With phenotypic drug screening

being superior in discovery of first-in-class compounds compared to target-based approaches zebrafish-based screens promise to yield novel treatment strategies21. Different imaging setups

(wide field, confocal) have been employed towards automated imaging of zebrafish xenografts including a pioneering work using a high-content imager, but so far these have not been broadly

applied likely due to remaining technical challenges11,22,23. Here, we provide a refined and robust workflow for high-content imaging of larval zebrafish xenografts. We reinvestigated the

suitability of different injection sites and dyes for various cell lines from different tumor entities. In addition, we describe embedding methods for easy high-content imaging. Furthermore,

we show options for automated recognition of zebrafish larvae and tumor cells and automated quantification of tumor size over consecutive days by adapting commercially available

high-content imaging software. Our setup allows us to test the in vivo efficacy of compounds within only one week of time. Furthermore, we show that not only cell lines of various tumor

entities, but also patient-derived cells can be transplanted and grow in zebrafish larvae, providing the opportunity to evaluate personalized therapy responses in a clinically relevant time

span. Our workflow for high-content imaging-based drug screening and the established comprehensive compendium of zebrafish xenograft cancer models will serve as a valuable resource for

preclinical compound testing and can easily be adapted for additional tumor entities. RESULTS COMPARISON OF COMMONLY USED INJECTION SITES To evaluate location specific effects towards

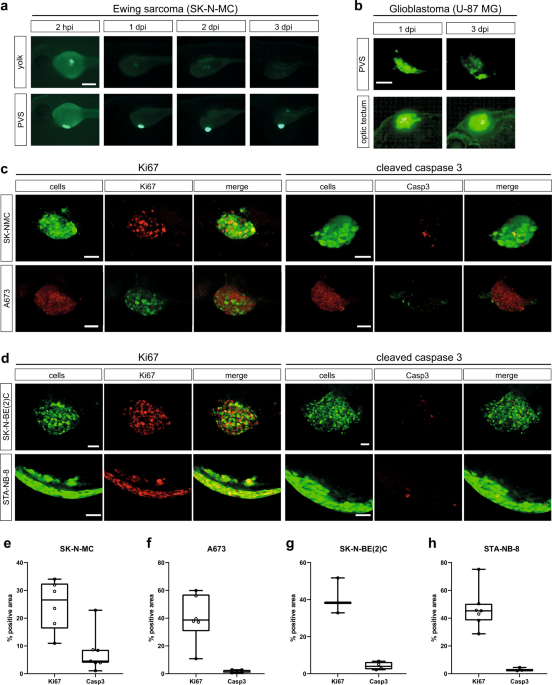

persistence of tumor cells in zebrafish and the ability to image the cells, we compared two commonly used injection sites, yolk and perivitelline space (PVS). With a main focus on pediatric

tumors and cell lines we initially investigated, if SK-N-MC Ewing sarcoma cells can survive and proliferate in the zebrafish embryo upon xenotransplantation at 2 days post fertilization

(dpf). To test this, we used the GFP-expressing SK-N-MC derivative cell line shSK-E17T24. We injected approximately 200–400 cells into the yolk or PVS, and monitored xenografted embryos for

3 consecutive days. Whereas cell numbers decreased in the yolk already after 24 h post injection (hpi) and were hardly recognizable after 3 days post injection, SK-N-MC cells transplanted

into the PVS persisted and increased in numbers (Fig. 1a). At 2 hpi we found tumor cells to be dispersed at the PVS injection site, but to form a compact mass by 1 day post injection (dpi)

(Supplementary Figure 1a), which increased in size over subsequent days (Fig. 1a). Ki67 immunofluorescence staining confirmed that GFP-expressing SK-N-MC as well as RFP-expressing A673 Ewing

sarcoma cells proliferate in zebrafish embryos/larvae up to 7 dpi, the latest time point we monitored (Fig. 1c, left panel and Supplementary Figure 1b). Staining for activated Caspase 3

showed hardly any apoptotic cells (Fig. 1c, right panel). Furthermore, injection of Ewing sarcoma cells into transgenic larvae with labeled vasculature _Tg(kdrl:Hsa.HRAS-mCherry)__s896_

revealed angiogenesis towards tumor masses at 3 dpi (Supplementary Figure 1c). These results indicated that the PVS is a suitable injection site for Ewing sarcoma cells and likely other

solid tumor cells. In addition to Ewing sarcoma cells, we also tested PVS engraftment of a neuroblastoma cell line with _MYCN_ oncogene amplification, SK-N-BE(2)C (engineered to express

H2B-GFP) and a patient-derived culture of neuroblastoma bone marrow metastasis, STA-NB-8 (_MYCN_ amplified, _ALK_ mutated). Similar to SK-N-MC and A673, SK-N-BE(2)C formed a compact tumor

cell cluster, however, STA-NB-8 stayed dispersed and crescent-shaped at the injection site. SK-N-BE(2)C and STA-NB-8 were positive for Ki67 in zebrafish and showed almost no activated

Caspase 3, indicating that the PVS is a permissive injection site (Fig. 1d). Quantification of immunofluorescence staining confirmed a comparable level of Ki67-positive cells across tested

tumor types, as well as low numbers of cells positive for cleaved Caspase 3 (Fig. 1e-h). However, for selected brain tumor cell lines, we noted that injection into the PVS did not support

tumor cell maintenance. We used GFP-expressing U-87 MG glioblastoma cells to compare PVS to orthotopic injection into the brain (optic tectum). While cells decreased in the PVS, we observed

that the optic tectum environment maintained U-87 MG cells and we quantified a slight increase (1.2-fold) in tumor size from 1 dpi to 3 dpi (Fig. 1b, Supplementary Figure 2). AUTOMATED

HIGH-CONTENT IMAGING OF ZEBRAFISH XENOGRAFTS In order to screen small compounds for tumor-growth-inhibiting effects at medium to high-throughput, we next sought to automate image acquisition

and image analysis of xenografted zebrafish larvae enabling reproducible quantification of tumor sizes at different time points. Adapting a cell-based drug screening setup, we applied a

high-content imager (Operetta CLS, PerkinElmer) for automated image acquisition of xenografted zebrafish larvae in 96-well plate format (Fig. 2a). Proper positioning of zebrafish larvae is

crucial for time-efficient imaging. Initially, we imaged zebrafish xenografts in commercial square bottom plates (ibidi), well suited for high-content imaging of cells in 2D. To image only

the areas where zebrafish larvae are located inside the well, we applied a prescan/rescan strategy. We initially recorded the wells at low magnification (5x objective) to obtain an overview

image. We trained the Operetta CLS Harmony software to detect the zebrafish in the well based on differences in texture in the image of the brightfield channel, and only re-imaged the areas

covered by the larva at higher magnification for detailed images (20x) (Fig. 2b). This strategy enabled automated image acquisition at high resolution of considerable sample numbers in a

reasonable time frame. We also explored options for further reducing the imaging area within the wells even at lower magnification. Here, we aimed for reproducibly positioning zebrafish in

the wells by using imaging plates with an insert, which keeps zebrafish centric in the well. To achieve this, we used 96-well imaging plates with pre-defined slots for zebrafish larvae (ZF

plates, Hashimoto) (Fig. 2c). This setup allowed us to record images of xenografted larvae in brightfield and fluorescence in confocal quality at higher throughput. Typical imaging time for

one plate with 96 larvae was around 60 min (5x air objective, 2 fields of view, 23 planes per larva, brightfield and one fluorescence channel). As the original ZF plates only allowed for

imaging with 5x air objectives due to their thick glass bottom, we also explored alternatives and developed 3D-printed inserts customized for commercially available high-content imaging

plates like ibidi view plates (Fig. 2d, Supplementary Figure 3a). As some zebrafish xenografts like orthotopic brain injections might require dorsal imaging, we also adapted an existing

protocol to 3D print stamps that produce slots in agarose for dorsal positioning of larvae in imaging plates (Fig. 2e, Supplementary Figure 3b)25. In summary, we provide robust setups that

allow for fast and reproducible lateral or dorsal automated high-content imaging of (xenografted) zebrafish larvae. AUTOMATED TUMOR DETECTION AND TUMOR SIZE QUANTIFICATION To automate tumor

cell detection and quantification of the size of the tumor cell cluster, we adopted analysis modules of the Harmony software (PerkinElmer) for our specific application in zebrafish (Fig.

3a). First, tumor detection was performed according to fluorescence intensity. Common thresholds were set according to the signal strength of individual cell lines to ensure proper tumor

detection. We compared two different analysis methods to evaluate tumor size, both based on recording a 3D stack of the tumor: volume and footprint area analysis. While actual volume

measurements are theoretically superior to area measurements of objects with complex shapes, we encountered practical limitations for precise volume measurements. Even in confocal mode we

observed significant scattering around the non-transparent tumor cell mass resulting in a blurred halo, especially along the z-direction. Indeed, when we compared calculated volumes of

almost spherical tumors with our measurements, we found that measured volumes were significantly overestimating actual volumes (5- to 6-fold) (Supplementary Figure 4). Alternatively, we

projected the tumor shape into a single plane (footprint projection) and measured tumor area. This footprint projection reliably provided measurements in good agreement with our observations

for spherical tumors. Hence, we subsequently applied footprint projection to measure the tumor size in xenografted zebrafish (Fig. 3c). AUTOMATED QUANTIFICATION CAN BE APPLIED ACROSS TUMOR

ENTITIES Next, we investigated if different cancer cell types with diverse genetic background (Table 1) would persist and would be quantifiable when xenografted into zebrafish larvae with

our analysis. Using our established setup, we xenografted various cell lines from different, mostly pediatric, tumor entities including Ewing sarcoma, neuroblastoma, osteosarcoma,

medulloblastoma, glioblastoma and acute lymphoblastic leukemia. For Ewing sarcoma we also generated a xenograft model from patient-derived cells, which had been passaged through a mouse PDX

model (IC-pPDX-8726,) and for neuroblastoma from a short-term 2D culture (STA-NB-8) (Fig. 3b, c). All xenotransplanted larvae were imaged at 1 dpi and 3 dpi. Subsequently, the relative

change in tumor size (3 dpi/1 dpi) was calculated to determine changes over the 48 h time span (>1: increase; =1: stagnation; <1: decrease). Among Ewing sarcoma cell lines, SK-N-MC

(SKshctrl) cells increased 2.6-fold on average whereas A-673 cells had a slower growth rate with an increase in area of about 1.4-fold. TC32 Ewing sarcoma cells decreased in tumor area

(relative change: 0.6-fold), while patient-derived-cells IC-pPDX-87 expanded 1.4-fold. Transplanted OS143B osteosarcoma cells increased 2-fold in size. Within the neuroblastoma panel _MYCN_

amplified SK-N-BE(2)C cells engrafted best with a 1.5-fold increase over 48 h. SK-N-MM cells, which carry _ATRX_ whole exon deletions resulting in in-frame fusions (_ATRX_mut), decreased

slightly over time (relative average change: 0.75-fold) and the PDX STA-NB-8 (_MYCN_ amplified, _ALK_ mutated) maintained their size (1-fold change). To exclude that the differences in

engraftment and growth among the three tested neuroblastoma cultures is caused by maintaining zebrafish xenografts at 34 °C, we investigated in vitro growth rates at 34 °C and 37 °C, but did

not observe any significant difference (Supplementary Figure 5). In xenografts with the medulloblastoma cell line HD-MB03 a small increase in tumor area with a relative change of 1.1-fold

could be assessed over the course of 48 h. U-87 MG glioblastoma cells injected orthotopically into the brain showed a relative increase in tumor area of 1.2-fold. In addition to solid tumor

detection, we also automated the detection of acute lymphoblastic leukemia cells injected into circulation of zebrafish larvae. Previously, we have demonstrated that Nalm-6 cells in

zebrafish larvae stain positive for Ki67 and we analyzed cell numbers by manual counting27. Here, applying a spot count algorithm of the Harmony software we were able to determine cell

numbers in an automated fashion. The analysis shows that leukemic Nalm-6 cells are maintained over 48 h in zebrafish larvae without any changes (relative change: 1-fold). CELLTRACE VIOLET IS

SUPERIOR TO CM-DII FOR LABELING TUMOR CELLS IN ZEBRAFISH XENOGRAFTS Not all tumor cells, especially low passage primary or patient-derived cells carry an intrinsic fluorescent label/express

fluorescent proteins. Thus, dyes to reliably label such cells for automated imaging are needed. We compared CellTraceTM Violet with CellTrackerTM CM-DiI (DiI), the most commonly used dye in

zebrafish xenografts to see whether they are suitable for our automated setup. For validation we labeled GFP-expressing SK-N-MC (SKshctrl) Ewing sarcoma cells with either CellTrackerTM

CM-DiI or CellTraceTM Violet (Fig. 4a). CellTrackerTM CM-DiI is a lipophilic membrane dye, while CellTraceTM Violet is a cytoplasmic stain. It belongs to the class of succinimidyl esters and

binds free amines within the cells28. No significant difference in tumor growth in unlabeled cells compared to cells either labeled with DiI or CellTraceTM Violet could be detected when

tumors were analyzed based on their GFP fluorescence, indicating that none of the dyes affects proliferation at applied concentrations (Fig. 4b). Also, no significant difference in detection

of primary tumors at 1 dpi or 3 dpi with both dyes was recognized (Fig. 4c, d). Next, we sought to compare the quantification of cells that have migrated out of the primary tumor site after

injection. Here, we applied two different analysis methods: 1) a spot count algorithm and 2) quantification of fluorescent area outside the primary tumor. With the spot count analysis

CellTraceTM Violet was reliably staining GFP-positive tumor cells in circulation. In contrast, with DiI significantly more objects were detected compared to the GFP signal (Fig. 4e, f,

Supplementary Figure 6a, b). In general, we often detected DiI-labeled particles in the caudal hematopoietic tissue even in the complete absence of GFP-positive cells in this region

(Supplementary Figure 6c). The same trend was observed by quantification of the fluorescent area. When cells were labeled with CellTraceTM Violet only a slightly larger area of disseminated

cells was detected (Supplementary Figure 6d). This small discrepancy was mainly caused by the autofluorescence of the otolithes (Supplementary Figure 6e). However, when cells were labeled

with DiI a substantially higher amount of fluorescent area was recognized outside the primary tumor region in the tail (Supplementary Figure 6f). The deviation from the GFP signal was

significantly higher in DiI- vs. CellTraceTM Violet-labeled cells, suggesting erroneous results with DiI labeling (Supplementary Figure 6g). FAST TESTING OF TARGETED COMPOUNDS AT

HIGH-THROUGHPUT IN VIVO To demonstrate that our setup is well suited for single and combination drug testing we performed a proof-of-principle small compound screen using molecules targeted

against Ewing sarcoma, osteosarcoma, glioblastoma, and neuroblastoma. For treatment of Ewing sarcoma xenografts we chose YK-4–279, described as inhibitor of EWS::FLI1/RNA helicase A

interactions and microtubule polymerization, which has been reported to induce apoptosis in Ewing sarcoma cells and lead to growth reduction in a mouse xenograft model29,30. For Ewing

sarcoma as well as osteosarcoma it has recently been reported that the YAP/TEAD axis could serve as a potential target31,32. Therefore, we investigated the TEAD inhibitor K-975 for Ewing

sarcoma and osteosarcoma treatment in our study33. Recently, inhibitors of anti-apoptotic proteins gained attention as alternative therapy target, hence we tested the BCL-XL inhibitor

A-1331852 against orthotopically injected glioblastoma xenografts. Xenografts with neuroblastoma cells were treated with the chemotherapeutic drug Temozolomide (under clinical investigation

for treatment of refractory/relapsed neuroblastoma: NCT02308527 or NCT01467986) and the ALK inhibitor (ALKi) Ceritinib34,35. Aiming to treat zebrafish xenografts at maximum tolerated

concentrations, the “No Observed Effect Concentrations” (NOECs) of YK-4-279, K-975, Temozolomide, Ceritinib and the combination of Temozolomide plus Ceritinib were determined. Here, we

scored overall survival and developmental abnormalities including edema formation (Fig. 5a). NOECs were assessed under identical experimental conditions (age of larvae, start and duration of

treatment, temperature) as in the xenograft setting and were found to be 5 µM for YK-4-279, 2 µM for K-975, 2 mM for Temozolomide, 2 µM for Ceritinib and 2 mM Temozolomide + 2 µM Ceritinib

for their combination (Fig. 5b–f). The NOEC for A-1331852 (10 µM) was already determined in a previous study, where we identified dual MCL-1/BCL-XL inhibition to be highly efficient against

EwS xenografts36. For compound testing, xenotransplanted larvae were imaged at 1 dpi followed by 48 h of compound treatment. At 3 dpi larvae were imaged again and tumor sizes were evaluated

(Fig. 6a). The growth of SK-N-MC Ewing sarcoma xenografts was significantly decreased when treated with YK-4-279 from 2-fold to 1.3-fold. This effect was shown to be dose-dependent

(Supplementary Figure 7). In addition, K-975 also caused a tumor growth halt down to 1.1 fold (Fig. 6b). Similarly, in osteosarcoma xenografts application of 2 µM K-975 led to a decrease

(1.7-fold to 1-fold) in tumor growth (Fig. 6c). Glioblastoma xenografts incubated in A-1331852 containing medium were significantly smaller (1-fold change) than the DMSO-treated group

(1.3-fold increase (Fig. 6d). For Neuroblastoma cell line STA-NB-8 (_ALK_F1174L) we found in vitro that it is more sensitive to Temozolomide and Ceritinib than SK-N-MM or SK-N-BE(2)C (both

_ALK_wt) (Supplementary Figure 8a, b). In zebrafish, we could observe significant reduction in tumor area of Temozolomide-treated STA-NB-8 xenografts, whereas Ceritinib had no significant

effect in vivo. Combination treatment of Temozolomide and Ceritinib did not show any enhanced effects (Fig. 6d). In contrast, _ALK_wt xenografts showed no significant response upon single

agent treatment and either no (SK-N-BE(2)C) or a small response upon combination treatment (SK-N-MM) (Supplementary Figure 8c, d). Zebrafish xenografts also promise to be a fast in vivo

anti-tumor efficacy verification model for completely novel compounds. To showcase such an application, we investigated newly synthesized Hsp90 inhibitors. Hsp90 serves as a chaperone

ensuring the proper folding of more than 400 client proteins, with many of them involved in oncogenesis. Interestingly, EWS::FLI1, the driver of EwS is a client itself and previous data

reported efficacy of an Hsp90 inhibitor against EwS cells37. Most current Hsp90 inhibitors are targeted against the N-terminal domain (e.g., 17-DMAG, Fig. 7a) and suffer from induction of

heat shock response (HSR), which limits their clinical efficacy. To overcome this problem, we designed allosteric C-terminal Hsp90 inhibitors, which should not cause HSR (e.g., TSF-15, Fig.

7a, Supplementary Figure 9). After in vitro tests against EwS cells (Supplementary Figure 11), we evaluated promising compounds in EwS zebrafish xenografts and observed an in vivo activity

for TSF-15 similarly to 17-DMAG at comparable concentrations, indicating that this compound is a starting point for further structural optimization (Fig. 7b). Ultimately, this illustrates

that our setup is suitable for preclinical screening of newly synthesized compounds and previously reported targeted therapies as single agents as well as in combination with a chemotherapy

backbone for pediatric tumor entities within the short time span of one week. DISCUSSION Larval zebrafish xenografts are gaining increasing attention in cancer research and precision

oncology as a vertebrate model system complementary to mouse xenografts18. Zebrafish larvae are well suited for small compound screening and several approaches towards automating key steps

in the drug screening workflow have been undertaken, including applying automated high-content imaging19. Despite successful proof-of-principles of high-content imaging-based analysis of

zebrafish xenografts11,19, this approach has not been widely adopted subsequently and the potential of zebrafish xenografts for the discovery of new therapeutic compounds by automated

high-throughput high-content screening has not been fully exploited yet. Here, we provide a robust protocol for high-content imaging-based analysis of zebrafish xenografts, which may find

wide application for different tumor entities. We already demonstrated the reliability of our workflows for identifying new drug combinations with high efficacy against Ewing sarcoma36.

Especially the combination of irinotecan with anti-apoptotic protein inhibitors targeted against MCL-1 and BCL-XL or dual MCL-1/BCL-XL was highly efficient36. In addition, we established and

characterized a comprehensive compendium of zebrafish xenograft cancer models with different pediatric tumor cell lines, which can be applied in preclinical compound testing. Our setup

enabled us to identify effects of small compounds on tumor growth in zebrafish xenografts with Ewing sarcoma, osteosarcoma, glioblastoma, and neuroblastoma cells. Of note, we provide in vivo

evidence for efficacy of YAP/TAZ/TEAD inhibition by K-975 against Ewing sarcoma and osteosarcoma xenografts. In addition, we show the benefit of our platform for fast in vivo investigation

of newly synthesized compounds, which can then be optimized in in vitro/in vivo iterative cycles. The here reported efficacy of YAP/TAZ/TEAD and Hsp90 inhibition might provide new treatment

strategies against Ewing sarcoma and osteosarcoma, most likely then combined with chemotherapy. Here, we also showcase that such clinically relevant combination treatments, such as ALKi in

combination with chemotherapy in neuroblastoma, can be investigated in vivo using our workflow within only one week. This is of particular relevance, since ALKi are the first targeted drugs

in first-line treatment of pediatric cancer34,38. We observed discrepancies between in vitro and in zebrafish response to ALKi in _ALK_F1174L models. In line with our observation, a loss of

response to the ALKi Ceritinib was also observed in vitro upon epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition and in phase I trials in children with ALK-positive malignancies35,39,40,41,42. In turn,

we observed an additive effect of ALKi and chemotherapy in an _ALK_wt xenograft model (SK-N-MM). While we currently do not understand the molecular basis of these differences, the zebrafish

xenografts recapitulate aspects of response (and resistance) in patients and might be useful models to study these properties. We revisited several practical aspects of xenotransplantation

including injection site and cell labeling. Although the yolk is a popular injection site for xenotransplantation of tumor cells into zebrafish due to easy accessibility, we observed better

tumor formation and growth when targeting the PVS. In addition, tumor cells injected deep into the yolk are harder to image than tumor cells in the rather superficial PVS. Despite a general

good persistence of tumor cells of different entities when injected into the PVS, we did also observe specific site requirements for glioblastoma cells. In our hands U-87 MG cells grew

better when injected orthotopically into the brain43. This may suggest that some zebrafish-derived growth-promoting factors are only present in this particular microenvironment. Thus,

orthotopic injection might also be necessary for other tumor entities in order to establish zebrafish xenografts. To label tumor cells for imaging, CellTrackerTM CM-DiI is the most prevalent

dye in zebrafish xenograft literature. We compared CellTrackerTM CM-DiI with Cell Trace VioletTM. While both dyes performed well in labeling tumor cell clusters at the primary injection

site in the PVS, Cell Trace VioletTM largely outperformed CellTrackerTM CM-DiI in faithfully highlighting disseminated cells. We often detected DiI-labeled particles in the caudal

hematopoietic tissue in the absence of actual GFP-expressing tumor cells. As a lipophilic dye, DiI likely also still labels dead cells and cell fragments even after uptake by macrophages and

might even get transferred to other cells11. The transfer of DiI between living and dead cells was indicated in Kruyt et al.44. To increase the drug screening throughput, we established a

robust and automated workflow for image acquisition of xenografted zebrafish, tumor cell detection, and tumor size quantification using a high-content imager (Operetta CLS, PerkinElmer).

While we show that it is possible to apply a prescan/rescan strategy to identify zebrafish in regular square bottom imaging plates, we found restricting the area where zebrafish are placed

in the well upfront with specific inserts reduces imaging time and increases throughput. Such a plate format is realized in commercially available ZF plates (Hashimoto). As the thick glass

bottom of the original ZF plates used in this study limited their application to low magnification objectives with longer working distances, we also developed 3D-printed inserts, which we

successfully used to modify ibidi view plates, but which can also be easily adapted to any desired plate. However, ZF plates are now also available with thinner glass bottoms better suited

for higher magnification objectives with shorter working distance. By using existing analysis modules of the Harmony software (PerkinElmer), we were able to detect tumor cells in zebrafish

xenografts in an automated way. This not only tremendously sped up tumor cell detection, but also ruled out biases as compared to manual annotation. Still, automated quantification of tumor

size remains a challenge. While volume quantification is the most accurate approach, this strategy is hampered by optical challenges, mainly scattering and absorption by human cells and also

acquisition time limitations for recording z-stacks with large numbers of planes for adequate 3D reconstruction. As we typically encountered 3D reconstructions distorted in z-direction

leading to overestimation of actual tumor volume, we turned to quantifying the tumor footprint area. This delivered reliable and reproducible results for following size changes of rather

spherical tumors. However, this projection approach has obvious limitations should a tumor alter size only along the z-direction. Furthermore, depending on the mode of action of the applied

compounds and the time needed to achieve effects, readouts other than tumor area measurements might be necessary. In summary, we present a setup for high-content imaging-assisted compound

screening on zebrafish xenografts for a variety of tumor entities. A checklist with common considerations when applying zebrafish xenografts for drug screening is provided in Supplementary

Figure 12. The zebrafish xenograft model together with automated imaging and image analysis as shown here promises to be a powerful system widely applicable for drug testing for human tumor

entities bridging the gap between in vitro screening and mouse xenografts. Furthermore, by using patient-derived zebrafish xenografts4 this setup can be adapted for personalized medicine

approaches to identify patient-tailored drugs and drug combinations within a clinically relevant time span. MATERIALS AND METHODS ZEBRAFISH STRAINS AND HUSBANDRY Zebrafish (_Danio rerio_)

were housed under standard conditions45,46 according to guidelines of the local authorities (Magistratsabteilung 58) under licenses GZ:565304-2014-6 and GZ:534619-2014-4. For all experiments

transparent zebrafish mutants (mitfab692/b692; ednrbab140/b140) or transparent zebrafish with labeled vasculature (mitfab692/b692; ednrbab140/b140, kdrl:Hsa.HRAS-mCherrys896tg) were used.

Experiments were performed under license GZ:333989-2020-4. CELL CULTURE GFP-expressing SK-N-MC cells (shSK-E17T24, SKshctrl), TC32 (kindly provided by Heinrich Kovar, CCRI, Austria), OS143B

(kindly provided by Chrystal Mackall, Stanford University, USA) and Nalm-6 cells were cultured in RPMI 1640 medium with GlutaMAXTM (Gibco, Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA) supplemented with

10% (v/v) FBS and 1% (v/v) Penicillin-Streptomycin (P/S) (10,000 U/ml, Gibco, Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA). shSK-E17T cells particularly were cultured on manually fibronectin-coated

plates. Neuroblastoma cell lines, SK-N-BE(2)C-H2B-GFP (kindly provided by Frank Westermann, DKFZ, Germany), SK-N-MM (kindly provided by Nai-Kong Cheung, Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer

Center, US) and a patient-derived culture, STA-NB-8 (established by the authors), were grown in RPMI 1640 medium with GlutaMAXTM supplemented with 10% (v/v) FBS, 80 units/ml penicillin, 80

µg/ml streptomycin (Thermo Fisher Scientific, 15140122, USA), 1 nM sodium pyruvate (Pan-Biotech, P0443100, Germany) and 25 mM Hepes buffer (Pan-Biotech, P0501100, Germany). DsRed expressing

HD-MB03 cells were cultured in RPMI + 10% (v/v) FBS + 1% P/S (v/v) supplemented with 1% (v/v) NEAA (100x, #11140050, Gibco, Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA). TagRFP expressing A673-1c24 and

GFP-expressing U-87 MG cells were expanded in DMEM with GlutaMAXTM (Gibco, Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA) supplemented with 10% (v/v) FBS, 1% (v/v) Penicillin-Streptomycin, A673-1c were

further supplemented with 10 µg/ml Blasticidin (InvivoGen, USA) and 50 µg/ml Zeocin (InvivoGen, USA). Primary Ewing sarcoma cells were obtained from a mouse patient-derived xenograft

(IC-pPDX-8747) (see Table 1). Mouse PDX experiments of this study were performed in accordance with the recommendations of the European Community (2010/63/UE) for the care and use of

laboratory animals. Experimental procedures using patient samples left over after diagnostic procedures were specifically approved by the ethics committee of the Medical University of Vienna

(EK1853/2016, EK1216/2018) and Institut Curie CEEA-IC #118 (Authorization APAFIS#11206-2017090816044613-v2 given by National Authority) in compliance with the international guidelines.

Written informed consent by patients or their legal representatives allowing generation of PDX models was obtained. Tumor pieces were dissociated according to Stewart et al. and IC-pPDX-87

cells were short-term cultured (<5 passages) in DMEM/F-12 with GlutaMAXTM (Gibco, Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA) supplemented with 1% (v/v) B-27 (50X, Gibco, Thermo Fisher Scientific,

USA) and 1% (v/v) P/S48. HEK293T cells were used only for lentiviral particle production and were grown in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% (v/v) FBS, 2 mM

L-glutamine, 100 units/ml penicillin, and 100 μg/ml streptomycin. All cells were kept in an atmosphere with 5% CO2 at 37 °C. At 90% confluence cells were passaged using Accutase (Pan

Biotech, Germany). VIABILITY ASSAY AT LOWER TEMPERATURE Neuroblastoma cells were seeded in T-25 flasks (750,000 cells/flask) and incubated for three days at 34 °C or 37 °C. Then the cells

were harvested and were manually counted using a hemocytometer. IN VITRO DRUG DOSE–RESPONSE ASSAYS Cells were seeded in 96-well white opaque plates (Cat. No. 6005680, PerkinElmer, USA,) and

incubated at 37 °C for 24 h. They were then treated with increasing concentrations of Ceritinib or Temozolomide and 72 h later cell viability was measured with the CellTiter-Glo® Luminescent

Cell Viability Assay (Cat. No. G7573, Promega, USA)) following the manufacturer’s instructions. LENTIVIRAL TRANSFECTION OF CELL LINES The neuroblastoma cell line SK-N-MM and patient-derived

culture STA-NB-8 with stable GFP expression were generated by lentiviral spinfection following the appropriate biological safety regulations. To deliver plasmids to generate the lentiviral

particles encoding the GFP protein, lipofectamine 3000 (ThermoFisher Scientific, USA) was used according to the manufacturer´s protocol. 10 μg of the plenti plasmid pCLS-CV49 encoding the

GFP protein was incubated with 5.4 μg of packaging plasmids (pMDLg/pRRE #11251, pRSV-Rev #11253, pMD2.g #12259, all from Addgene, USA) in 1500 μl Opti-MEM I (ThermoFisher Scientific, USA)

with 30 µl P3000 enhancer (ThermoFisher Scientific, USA). The mixture was vortexed for 10 s. In a separate mix, 46 μl of lipofectamine 3000 (ThermoFisher Scientific, USA) was added to 1500

μl Opti-MEM I and was gently added to the first mixture followed by 4 min incubation at room temperature. The transfection mix was added drop-wise to a 10-cm dish of ~70% confluent HEK293T

cells. 6 h post-transfection, the medium was replaced with lentiviral packaging medium (Opti-MEM I, 5% FCS, 200 µM sodium pyruvate). 24 h later, the lentiviral medium was collected and

filtered through 0.45 µm filters. Target cells (~60% confluent) were spinfected with the optimized titer of the lentiviral medium by centrifugation at 800 × _g_ for 45 min at 32 °C.

Spinfected cells were recovered for one day in fresh medium and GFP expression was confirmed by flow cytometry. PREPARATION OF CELLS FOR TRANSPLANTATION To prepare fluorescently labeled

cells for xenotransplantation cells were detached from the culture dish with Accutase (PAN-Biotech, Germany). After a centrifugation step (5 min, 500 × _g_, 4 °C) cells were taken up in PBS

supplemented with 2% FBS and put through a 35 µm cell strainer (5 ml polystyrene round bottom tubes with cell strainer cap, Corning, USA) to disperse cell clumps. Cell number was determined

using a Coulter Counter (Z2, Beckman Coulter, USA). Cells were then centrifuged, resuspended to a concentration of 100 cells/nl PBS and kept on ice until transplantation. CM-DII LABELING To

label cells with CellTrackerTM CM-DiI (Invitrogen, Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA) cells were harvested by incubation with protease. Subsequent to a regular counting and centrifugation

routine, cell number was adjusted to a concentration of 1 × 106 cells/ml in serum-free medium. For staining CM-DiI was mixed in at a concentration of 2 µg/ml. Cells were incubated with

CM-DiI for 5 min at 37 °C in the dark, followed by 15 min on ice still in the dark, then washed again twice with RPMI supplemented with 2% FBS. Pelleted cells were taken up in PBS

supplemented with 2% FBS. MgCl2 was added to a final concentration of 2 mM as well as DNase I to a final concentration of 50 µg/ml for 20 min incubation at 37 °C. After two PBS/2% FBS

washing steps, cells were put through a 35 µm cell strainer and total cell number was assessed. Cells were then centrifuged again, resuspended to a concentration of 100 cells/nl in PBS and

kept on ice until transplantation. CELLTRACETM VIOLET LABELING To label cells with CellTraceTM Violet (Invitrogen, Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA) cells were harvested with Accutase and cell

numbers adjusted to a concentration of 1 × 106 cells/ml in PBS. CellTraceTM Violet was mixed into a final concentration of 5 µM. Cells were incubated with CellTraceTM Violet for 10 min at 37

°C in the dark. 5 volumes of medium supplemented with 10% FBS were added, and the suspension was incubated for 5 min. After centrifugation (5 min, 500 g, 4 °C) cells were resuspended in

fresh medium supplemented with 10% FBS and incubated for another 10 min in the dark. Finally, sticky cells were separated by means of a 35 µm cell strainer and then counted. Cells were

centrifuged again, resuspended to a concentration of 100 cells/nl in PBS and kept on ice until transplantation. XENOTRANSPLANTATION mitfab692/b692; ednrbab140/b140 embryos were raised until

2 days post fertilization (dpf) at 28 °C, dechorionated and anesthetized with 1x Tricaine (0.16 g/l Tricaine (Cat No. E1052110G, Sigma-Aldrich Chemie GmbH, Germany), adjusted to pH 7 with 1

M Tris pH 9.5, in E3). To facilitate the transplantation process larvae were aligned on a petri dish lid coated with a solidified 2% agarose solution as described previously16. The

borosilicate glass capillaries without filament (GB100T-8P, Science Products GmbH, Germany) for injection of tumor cells were pulled with a needle puller (P-97, Sutter Instruments, USA).

Needles were loaded with ~5 µl of cell suspension, mounted onto a micromanipulator (M3301R, World Precision Instruments Inc., Germany) and connected to a microinjector (FemtoJet 4i,

Eppendorf, Germany). Approximately 200–400 cells were transplanted into the perivitelline space (PVS), the optic tectum or into circulation of zebrafish larvae. Following an inspection under

the microscope larvae carrying tumor cells only at/ in the respective injection site at 2 h post injection (hpi) were selected and subsequently maintained at approx. 34 °C. WHOLE MOUNT

IMMUNOSTAINING Xenotransplanted larvae were fixed in 4% PFA (Electron Microscopy Sciences, USA) in PBS overnight at 4 °C. Larvae were washed once with PBS and then gradually transferred to

100% MetOH for storage at −20 °C. For immunostaining, larvae were gradually transferred back to PBS. After washing once with PBSX (PBS with 0.1% Triton X-100) and washing once with plenty

distilled water, larvae were incubated in acetone for 7 min at −20 °C. Larvae were blocked for 1 h in PBDX (PBS with 0.1% Triton X-100, 0.1 g/l BSA, 0.1% DMSO) supplemented with 15 µl goat

serum (GS) (normal donor herd, Sigma-Aldrich, USA)/ml PBDX. Dilutions of primary antibodies against Ki-67 (1:400) ((8D5) mouse primary mAb #9449, Cell signaling Technology, USA) and Cleaved

Caspase 3 (1:100) ((D175) primary antibody, Cell Signaling Technology, USA) in PBDX + GS were prepared. Antibody incubation routine for larvae was in primary antibody solution overnight at 4

°C, followed by 4x washing in PBDX for 30 min, then secondary antibodies Alexa 568 anti-mouse (A-11019, Invitrogen, USA) or Alexa 568 anti-rabbit (A-21069, Invitrogen, USA) diluted 1:500 in

PBDX + GS for 1 h. From this point on all steps were carried out ensuring that samples are kept in the dark. Larvae were washed twice with PBDX and 1x with PBS, followed by an incubation in

4% PFA for 5 min. Larvae were washed 3 times with PBS, transferred to Dako Fluorescence Mounting Medium (Dako, Agilent, USA), and stored at 4 °C. IMAGING Fluorescence images of anesthetized

larvae were acquired using an Axio Zoom.V16 fluorescence stereo zoom microscope with an Axiocam 503 color camera from Zeiss (Zeiss, Germany) using the image ZEN software (Zeiss, Germany).

Fixed and immunostained larvae were embedded in 1.2% ultra-low gelling agarose (Cat. No. A2576-25G, Sigma-Aldrich Chemie GmbH, Germany) in a glass bottom imaging dish (D35-14-1.5-NJ,

Cellvis, USA) as previously described50. Imaging was performed using a SP8 X WLL confocal microscope system and the LASX software (Leica, Germany). QUANTIFICATION OF IMMUNOFLUORESCENCE

Confocal images of immunostained xenotransplanted tumors were quantified using the ImageJ software (version 1.53c). Images were split into green and red channels and threshold was set

manually to detect the fluorescence area. Fluorescence area was determined for whole tumor versus Ki67- and cleaved Caspase 3-signals and percentages were calculated. AUTOMATED IMAGING AND

QUANTIFICATION For automated imaging at 1 and 3 dpi larvae were anesthetized in 1x Tricaine and embedded in either an ibidi µ-plate with glass bottom (Cat. No. 89627, Ibidi, Germany) or a

96-well ZF plate (Cat. No. HDK-ZFA 101, Hashimoto Electronic Industry Co, Japan). Larvae were transferred with minimal residual volume into 0.5% ultra-low gelling agarose/1x Tricaine (Cat.

No. A2576-25G, Sigma-Aldrich Chemie GmbH, Germany) as a compromise concentration between mechanical support for proper orientation of larvae and easy retrieval after imaging. Using large

orifice tips (Cat. No. E1011-8400, Starlab, USA) xenografted larvae were pipetted into the respective well in a volume of 200 µl. GELoadertips (Cat. No. 0030001.222, Eppendorf, Germany) were

used to gently orientate the larvae into the correct position (head left) towards the bottom of the well. After imaging, large orifice tips were used again to pipette larvae out of the

imaging plate into a drug treatment plate. The Operetta CLS high-content imager (PerkinElmer, USA) was used for image acquisition in confocal mode and with defined settings: 5x air

objective, Brightfield (40 ms, 10%), GFP (excitation: 460–490 nm at 100%, emission: 500–550 nm for 400 ms), DiI and tagRFP (excitation: 530–560 nm at 100%, emission: 570–650 nm for 400 ms),

CellTrace Violet (excitation: 390–420 nm at 100%, emission: 430–500 nm for 600 ms). Larvae were imaged in 2 fields of view (covers whole larvae), with 23 planes with a distance of 25 µm per

field (approx. optimal for this objective according to manufacturer). Tumor size was quantified with the Harmony Software 4.9 (PerkinElmer, USA). The area of the tumor projected along the

z-axis onto the x-y-plane (“footprint area”) was used for further analysis of tumor growth form 1 dpi to 3 dpi. In more detail, the slot area per well was defined in the brightfield channel

by threshold against the dark well walls to limit the area of analysis. Next, the fluorescence signal from tumor cells was detected by applying the lowest possible intensity threshold (vs

infinite highest intensity) at a scale suitable for all samples of the plate in the 3D analysis mode. In case tumor cells separated from the primary tumor, a size threshold was added to

select for the largest fluorescent bolus, which is typically the primary tumor. Aside from size, Harmony software can delineate position of detected fluorescence areas in X and Y. This

function can be used to find fluorescence signal in a specific area. In case of disturbing autofluorescence e.g., from the yolk it is advised to restrict the analysis to a certain region

this way. For detection of cells in circulation (Nalm-6 or migrated cells) either a spot detection algorithm of the Harmony software was used or the fluorescent area outside of the primary

tumor in maximum projection was quantified. 3D-PRINTED INSERTS FOR IMAGING Developing and processing of the inserts and stamps was conducted in three steps. Inserts and stamps were designed

using Autodesk Inventor professional 2020. The design of the stamps was adapted from Wittbrodt et al.25. Inserts and the stamps were printed with a Hot Lithography 3D printer (Caligma,

Cubicure GmbH, Vienna) using the photopolymer Cubicure Evolution (Cubicure GmbH, Austria). The printer polymerized the material layerwise using a UV-laser (wavelength: 375 nm). The thickness

of the individual layers was 100 µm. Printed parts were cleaned iteratively using an acetate-based solvent and an ultrasonic bath. Post curing was conducted at 70 °C. Inserts fit into Ibidi

96 Well Black µ-Plates (Cat. No. 89621, uncoated, Ibidi, Germany). To form stable grooves with the stamps, 300 µl 2% (w/v) ultra-low gelling agarose (Sigma-Aldrich Chemie GmbH, Germany) was

poured into each of the wells of an ibidi 96-well plate, the stamps were instantly inserted and for a few minutes left there while in the refrigerator. When agarose was solidified, stamps

were carefully removed. DETERMINATION OF “NO OBSERVED EFFECT CONCENTRATION” (NOEC)/COMPOUND TREATMENT YK-4-279 (Cat. No. HY-14507, MedChemExpress, Sweden), K-975 (Cat. No. HY-138565,

MedChemExpress, Sweden), A-1331852 (Cat. No. HY-19741, MedChemExpress, Sweden), 17-DMAG (Alvespimycin) (Cat. No. HY-10389, MedChemExpress, Sweden) and freshly synthesized Hsp90 inhibitors

were dissolved in DMSO to a stock concentration of 10 mM. Temozolomide (Cat. No. HY-17364, MedChemExpress, Sweden) and Ceritinib (Cat. No. HY-15656A) were dissolved in ddH2O to a stock

concentration of 10 mM. Not all compounds can be solved in water/E3 or DMSO. For alternative solvents and applicable concentrations in zebrafish we suggest the following article: Maes et

al., _Plos One_ 201251. Selection of the proper solvent should be based on informed decision considering solubility of compounds of interest as well as tolerance of larvae. As starting point

for NOEC determination, we typically investigate concentrations around 10x of in vitro IC50s. This matches a reported 10 % uptake by zebrafish larvae of compounds delivered to the water

(determined for paracetamol)52. Here, to define the highest tolerated concentration at approx. 34 °C various dilutions in fish E3 media of YK-4-279 (2,5 µM, 5 µM, 10 µM, and 20 µM), K-975 (1

µM, 2 µM, 4 µM and 8 µM),Temozolomide (0,5 mM, 1 mM, 2 mM and 5 mM) and Ceritinib (1 µM, 2 µM, 5 µM and 15 µM) were tested. Treatment of 10–12 pigment mutant zebrafish larvae in regular

12-well multi-well plates started at 3dpf. Impact on larval health and survival was assessed by inspection on a brightfield microscope at the end of a 48 h treatment. For drug screening

experiments, cells were transplanted into the PVS of 2 dpf old zebrafish larvae as described above. Tumor cells were allowed to grow for 24 h to form a compact tumor mass at the injection

site. After recording reference images of the xenotransplanted larvae at 1 dpi in the Operetta CLS, they were transferred to cell culture plates containing fresh E3 embryo medium and

accordingly compound in indicated concentrations for an incubation time of 48 h. The applied compounds did not need refreshment during treatment, as supernatant was still active at the end

of the assay (tested on fresh xenografts or during in vitro assays), but this needs consideration during experiment planning. Dishes containing light sensitive compounds were covered with

light protection. For easier pipetting compound treatments were conducted in 48-well or 24-well format (single larvae per well). At 3 dpi, larvae were imaged again post-treatment on the

Operetta CLS. CHEMISTRY The reagents and solvents for the synthesis were purchased from Enamine Ltd (Kyiv, Ukraine), Apollo Scientific Ltd (Stockport, UK) and Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO,

USA) and were used without further purification. Analytical thin-layer chromatography was performed on silica gel aluminum sheets (0.20 mm; 60 F254; Merck, Darmstadt, Germany) to monitor the

progress of the reactions, while flash column chromatography, used to purify the compounds, was performed on silica gel 60 (particle size, 230–400 mesh). A 400 MHz NMR spectrometer Bruker

Advance 3 (Bruker, Billerica, MA, USA) was used to record the 1H and 13C NMR spectra. The splitting patterns of the peaks were designated as s for singlet, d for doublet, dd for doublet of

doublet, ddd for double of doublet of doublet, and m for multiplet. The mass spectra of the prepared compounds were recorded using Expression CMSL mass spectrometer (Advion Inc., Ithaca, NY,

USA), while Exactive Plus Orbitrap mass spectrometer (Thermo Scientific Inc., Waltham, MA, USA) was used to record the high-resolution mass spectra (HRMS) of the final product. The purity

of TSF-15 was determined by analytical reversed-phase UHPLC on the Thermo Scientific Dionex UltiMate 3000 UHPLC modular system (Thermo Fisher Scientific) equipped with a photodiode array

detector set to 254 nm. A Waters Acquity UPLC® HSS C18 SB column (1.8 μm, 2.1 mm × 50 mm) thermostatted at 40 °C was used. The mobile phase consisted of 0.1% TFA in H2O (A) and MeCN (B),

using the following gradient: 95% A to 5% A in 7 min, then 95% B for 1 min, with a flow rate of 0.3 mL/min and an injection volume of 2.5 µL. 17-DMAG was purchased from MedChemExpress.

Synthesis of TSF-15 is presented in Supplementary Figure 9. Synthesis of (_S_)-_N_-(2-amino-4,5,6,7-tetrahydrobenzo[_d_]thiazol-6-yl)-3,4-dichlorobenzamide (TSF-2). 3,4-Dichlorobenzoic acid

(3.39 g, 17.8 mmol) was dissolved in _N_,_N_-dimethylformamide (DMF, 15 mL). EDC (3.31 g, 21.3 mmol), HOBt (3.53 g, 23.1 mmol) and NMM (3.86 mL, 35.5 mmol) were added on an ice bath. The

reaction mixture was stirred for 15 min and then (_S_)-4,5,6,7-tetrahydrobenzo[_d_]thiazole-2,6-diamine (3.00 g, 17.8 mmol) was added. The reaction mixture was stirred overnight at room

temperature. The solvent was evaporated under reduced pressure. EtOAc (50 mL) and NaHCO3 (50 mL) were added to the residue and a precipitate was filtered off. The precipitate was then washed

with MeOH to yield a clean product. Yield: 56% (3.400 g); white solid; Rf (DCM:MeOH = 9:1) = 0.37; 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-_d__6_): δ = 8.64 (d, _J_ = 7.6 Hz, 1H), 8.10 (d, _J_ = 2,1 Hz, 1H),

7.84 (dd, _J__1_ = 8.4 Hz, _J__2_ = 2.1 Hz, 1H), 7.76 (d, _J_ = 8.4 Hz, 1H), 6.68 (s, 2H), 4.23–4.13 (m, 1H), 2.86–2.76 (m, 1H), 2.00–1.91 (m, 1H), 1.88–1,75 (m, 1H) ppm, the signals of the

remaining protons are overlapped with the signal for DMSO-_d__6_ (Supplementary Figure 10a); MS (ESI+) for C14H14Cl2N3OS _m/z_: 341.9 [M + H]+. Synthesis of _tert_-butyl

(3-(((_S_)-6-(3,4-dichlorobenzamido)-4,5,6,7-tetrahydrobenzo[_d_]thiazol-2-yl)amino)-3-oxo-1-phenylpropyl)carbamate (TSF-10). 3-((_tert_-Butoxycarbonyl)amino)-3-phenylpropanoic acid (113 mg,

0.585 mmol) was dissolved in DMF. EDC (109 mg, 0.701 mmol), HOBt (116 mg, 0.760 mmol) and NMM (0.204 mL, 1.17 mmol) were added on an ice bath. The reaction mixture was stirred for 15 min

and then TSF-2 (200 mg, 0.585 mmol) was added. The reaction mixture was stirred overnight at room temperature. The solvent was evaporated under reduced pressure. The residue was taken up in

EtOAc (50 mL) and the organic phase was washed with 1% citric acid (2 × 50 mL), saturated NaHCO3 (2 × 50 mL), brine (50 mL) and dried over Na2SO4. The solvent was evaporated and the residue

was further purified by flash column chromatography using DCM:MeOH = 20:1 as the mobile phase. Yield: 40% (138 mg); light yellow solid; Rf (DCM:MeOH = 9:1) = 0.43; 1H NMR (400 MHz,

DMSO-_d__6_) δ 11.92 (s, 1H), 8.68 (d, _J_ = 7.5 Hz, 1H), 8.11 (d, _J_ = 2.0 Hz, 1H), 7.85 (ddd, _J__1_ = 8.5 Hz, _J__2_ = 2.0 Hz, _J__3_ = 0.8 Hz, 1H), 7.77 (dd, _J__1_ = 8.5 Hz, _J__2_ =

0.8 Hz, 1H), 7.51 (dd, _J__1_ = 8.8 Hz, _J__2_ = 4.0 Hz, 1H), 7.36–7.27 (m, 4H), 7.26–7.19 (m, 1H), 5.03 (q, _J_ = 8.0 Hz, 1H), 4.22 (s, 1H), 3.00 (dd, _J__1_ = 15.7 Hz, _J__2_ = 5.3 Hz,

1H), 2.83–2.77 (m, 2H), 2.72–2.63 (m, 2H), 2.07–1.97 (m, 2H), 1.95 – 1.81 (m, 1H), 1.39–1.18 (m, 9H) ppm (Supplementary Figure 10b); MS (ESI+) C28H31Cl2N4O4S _m/z_: 589.8 [M-H]+. Synthesis

of 3-(((_S_)-6-(3,4-dichlorobenzamido)-4,5,6,7-tetrahydrobenzo[_d_]thiazol-2-yl)amino)-3-oxo-1-phenylpropan-1-aminium chloride (TSF-15). To a solution of compound TSF-10 (60 mg, 0.102 mmol)

in 1,4-dioxane (20 mL) 4 M HCl in 1,4-dioxane (0.76 mL, 3.05 mmol) was added and the mixture was stirred overnight at room temperature. The solvent was evaporated under reduced pressure and

the solid residue was washed with 1,4-dioxane to yield a clean product. Yield: 84% (45 mg); white solid; Rf (DKM:MeOH = 9:1) = 0.0; 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-_d__6_) δ 12.16 (s, 1H), 8.69 (dd,

_J__1_ = 7.6 Hz, _J__2_ = 3.4 Hz, 1H), 8.50 (s, 3H), 8.10 (t, _J_ = 1.7 Hz, 1H), 7.84 (ddd, _J__1_ = 8.4 Hz, _J__2_ = 2.1 Hz, _J__3_ = 1.3 Hz, 1H), 7.77 (dd, _J__1_ = 8.4 Hz, _J__2_ = 1.3

Hz, 1H), 7.54–7.46 (m, 2H), 7.47–7.34 (m, 3H), 4.76–4.64 (m, 1H), 4.26–4.14 (m, 1H), 3.19–3.07 (m, 2H), 3.03–2.95 (m, 1H), 2.70–2.64 (m, 3H), 2.06–1.98 (m, 1H), 1.94–1.81 (m, 1H) ppm

(Supplementary Figure 10c); 13C NMR (101 MHz, DMSO-_d_6) δ 167.00, 163.63, 154.97, 143.38, 136.86, 136.84, 134.81, 133.96, 131.16, 130.64, 129.29, 128.81, 128.70, 127.79, 127.61, 127.59,

119.61, 50.96, 46.17, 46.13, 28.41, 28.09, 24.68 ppm (Supplementary Figure 10d); HRMS (ESI+) calcd. for C23H24Cl2N4O2S [M + H]+: 489.0913, found: 489.0907; UPLC: tr: 4.060 min (98.08% at 254

nm and 96.77% at 220 nm) (Supplementary Figure 10e, f). HSP90 C-TERMINAL DOMAIN TIME-RESOLVED FLUORESCENCE RESONANCE ENERGY TRANSFER (TR-FRET) ASSAY Hsp90α C-terminal domain TR-FRET kit was

purchased from BPS Bioscience (San Diego, USA) and assay was carried out according to manufacturer’s protocol. Sample contained terbium-labeled donor, dye-labeled acceptor, Hsp90α

C-terminal domain, PPID and TSF-15 or novobiocin (known Hsp90 CTD inhibitor) or 17-DMAG (known Hsp90 N-terminal domain inhibitor). Positive control contained no inhibitor, negative control

did not contain target protein PPID. Samples were incubated for 2 h, then protein–protein interaction between Hsp90 C-terminal domain and PPID was assayed by measuring TR-FRET using Tecan’s

Spark Multimode Microplate reader (Tecan Trading AG, Switzerland). Each sample was performed in triplicate. Percentage of C-terminal domain activity was calculated using the following

formula %Activity = 100 × (FRETsample – FRETnegative control)/(FRETpositive control – FRETnegative control), where FRET value is ratio between dye-acceptor emission and Tb-donor emission.

Statistical analysis was performed using one-way ANOVA post hoc Dunnett’s test (Supplementary Figure 11a). MTS ASSAY The antiproliferative activity of TSF-15 against an Ewing sarcoma cell

line SK-N-MC was evaluated, using an MTS (Promega, Madison, WI, USA) assay, according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The cells were cultured in RPMI medium with HEPES (Sigma-Aldrich,

St. Louis, MO, USA), which was supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Gibco, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA), 100 U/mL penicillin (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA), 100

µg/mL streptomycin (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA), and 2 mM L-glutamine (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA). The cells were incubated in a 5% CO2 atmosphere at 37 °C. For testing the

cells were plated in 96-well plates at a density of 2000 cells/well. Afterwards, the cells were incubated for 24 h, and then treated with TSF-15 and vehicle control (0.5% DMSO). Afterward,

the cells were incubated with the compound for 72 h and then CellTiter96 Aqueous One Solution Reagent (10 µL; Promega, Madison, WI, USA) was added to each well. The cells were incubated for

an additional 3 h and then the absorbance was measured using a microplate reader (Synergy 4 Hybrid; BioTek, Winooski, VT, USA). Independent experiments were repeated two times, each

performed in triplicate. The statistically significant differences (_p_ < 0.05) were calculated between the treated groups and DMSO, using two-tailed Welch’s t-tests. GraphPad Prism 8.0

(San Diego, CA, USA) was used to determine the IC50 value of TSF-15, which represents the concentration at which the compound produced a half-maximal response (given as means from the three

independent measurements) (Supplementary Figure 11b). 17-DMAG showed antiproliferative activity in SK-N-MC cell line with an IC50 of 0.01 ± 0.007 µM53. STATISTICAL ANALYSIS Statistical

analysis was performed in Prism 8 (Version 8.3.0, Graphpad, USA). Distribution of data was tested with a normality test (D’Agostino & Pearson). Based on data distribution either

parametric tests (student’s t-test or ANOVA) or non-parametric tests (Mann–Whitney test or Kruskal–Wallis test) were performed. The applied method is indicated in the figure legends.

REPORTING SUMMARY Further information on research design is available in the Nature Research Reporting Summary linked to this article. DATA AVAILABILITY The datasets generated during and/or

analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request. CODE AVAILABILITY CAD files for 3D-printed inserts are available from the following

repository: https://doi.org/10.48436/7qfnf-qpy18. REFERENCES * WHO, “Cancer”, https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/cancer (2022). * Xu, C., Li, X., Liu, P., Li, M. & Luo, F.

Patient-derived xenograft mouse models: a high fidelity tool for individualized medicine. _Oncol Lett_ 17, 3–10 (2019). CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Costa, B., Estrada, M. F., Mendes, R.

V. & Fior, R. Zebrafish avatars towards personalized medicine—a comparative review between avatar models. _Cells_ 9, https://doi.org/10.3390/cells9020293 (2020). * Fior, R. et al.

Single-cell functional and chemosensitive profiling of combinatorial colorectal therapy in zebrafish xenografts. _Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA_ 114, E8234–E8243 (2017). Article CAS PubMed

PubMed Central Google Scholar * Lee, L. M., Seftor, E. A., Bonde, G., Cornell, R. A. & Hendrix, M. J. The fate of human malignant melanoma cells transplanted into zebrafish embryos:

assessment of migration and cell division in the absence of tumor formation. _Dev. Dyn._ 233, 1560–1570 (2005). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Nicoli, S. & Presta, M. The

zebrafish/tumor xenograft angiogenesis assay. _Nat. Protoc._ 2, 2918–2923 (2007). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Veinotte, C. J., Dellaire, G. & Berman, J. N. Hooking the big

one: the potential of zebrafish xenotransplantation to reform cancer drug screening in the genomic era. _Dis. Model Mech._ 7, 745–754 (2014). Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

* Yan, C. et al. Visualizing engrafted human cancer and therapy responses in immunodeficient zebrafish. _Cell_ 177, 1903–1914.e1914 (2019). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google

Scholar * Barriuso, J., Nagaraju, R. & Hurlstone, A. Zebrafish: a new companion for translational research in oncology. _Clin. Cancer Res._ 21, 969–975 (2015). Article CAS PubMed

PubMed Central Google Scholar * Gauert, A. et al. Fast, in vivo model for drug-response prediction in patients with B-cell precursor acute lymphoblastic leukemia. _Cancers_ 12,

https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers12071883 (2020). * Cornet, C., Dyballa, S., Terriente, J. & Di Giacomo, V. ZeOncoTest: refining and automating the zebrafish xenograft model for drug

discovery in cancer. _Pharmaceuticals_ 13, https://doi.org/10.3390/ph13010001 (2019). * Povoa, V. et al. Innate immune evasion revealed in a colorectal zebrafish xenograft model. _Nat.

Commun._ 12, 1156 (2021). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Ali, Z. et al. Zebrafish patient-derived xenograft models predict lymph node involvement and treatment

outcome in non-small cell lung cancer. _J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res._ 41, 58 (2022). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Cully, M. Zebrafish earn their drug discovery

stripes. _Nat. Rev. Drug Discov._ 18, 811–813 (2019). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Rennekamp, A. J. & Peterson, R. T. 15 years of zebrafish chemical screening. _Curr. Opin.

Chem. Biol._ 24, 58–70 (2015). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Pascoal, S. et al. Using zebrafish larvae as a xenotransplantation model to study Ewing sarcoma. _Methods Mol. Biol._

2226, 243–255 (2021). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Grissenberger, S. et al. Preclinical testing of CAR T cells in zebrafish xenografts. _Methods Cell Biol._ 167, 133–147 (2022).

Article PubMed Google Scholar * Xiao, J., Glasgow, E. & Agarwal, S. Zebrafish xenografts for drug discovery and personalized medicine. _Trends Cancer_ 6, 569–579 (2020). Article CAS

PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Zhang, B. et al. Quantitative phenotyping-based in vivo chemical screening in a zebrafish model of leukemia stem cell xenotransplantation. _PLoS

ONE_ 9, e85439 (2014). Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Hason, M. et al. Bioluminescent zebrafish transplantation model for drug discovery. _Front. Pharmacol._ 13, 893655

(2022). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Swinney, D. C. & Anthony, J. How were new medicines discovered. _Nat. Rev. Drug Discov._ 10, 507–519 (2011). Article CAS

PubMed Google Scholar * Zhao, C. et al. A novel xenograft model in zebrafish for high-resolution investigating dynamics of neovascularization in tumors. _PLoS ONE_ 6, e21768 (2011).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Haney, M. G., Moore, L. H. & Blackburn, J. S. Drug screening of primary patient derived tumor xenografts in zebrafish. _J. Vis.

Exp_. https://doi.org/10.3791/60996 (2020). * Franzetti, G. A. et al. Cell-to-cell heterogeneity of EWSR1-FLI1 activity determines proliferation/migration choices in Ewing sarcoma cells.

_Oncogene_ 36, 3505–3514 (2017). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Wittbrodt, J. N., Liebel, U. & Gehrig, J. Generation of orientation tools for automated zebrafish

screening assays using desktop 3D printing. _BMC Biotechnol._ 14, 36 (2014). Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Surdez, D., Landuzzi, L., Scotlandi, K. & Manara, M. C.

Ewing sarcoma PDX models. _Methods Mol. Biol._ 2226, 223–242 (2021). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Pascoal, S. et al. A Preclinical embryonic zebrafish xenograft model to

investigate CAR T cells in vivo. _Cancers_ 12, https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers12030567 (2020). * Banks, P. R. & Paquette, D. M. Comparison of three common amine reactive fluorescent

probes used for conjugation to biomolecules by capillary zone electrophoresis. _Bioconjug. Chem._ 6, 447–458 (1995). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Erkizan, H. V. et al. A small

molecule blocking oncogenic protein EWS-FLI1 interaction with RNA helicase A inhibits growth of Ewing’s sarcoma. _Nat. Med._ 15, 750–756 (2009). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google

Scholar * Kollareddy, M. et al. The small molecule inhibitor YK-4-279 disrupts mitotic progression of neuroblastoma cells, overcomes drug resistance and synergizes with inhibitors of

mitosis. _Cancer Lett._ 403, 74–85 (2017). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Morice, S. et al. The YAP/TEAD axis as a new therapeutic target in osteosarcoma: effect of

verteporfin and CA3 on primary tumor growth. _Cancers_ 12, https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers12123847 (2020). * Bierbaumer, L. et al. YAP/TAZ inhibition reduces metastatic potential of Ewing

sarcoma cells. _Oncogenesis_ 10, 2 (2021). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Kaneda, A. et al. The novel potent TEAD inhibitor, K-975, inhibits YAP1/TAZ-TEAD

protein-protein interactions and exerts an anti-tumor effect on malignant pleural mesothelioma. _Am. J. Cancer Res._ 10, 4399–4415 (2020). CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar *

Bellini, A. et al. Frequency and prognostic impact of ALK amplifications and mutations in the European Neuroblastoma Study Group (SIOPEN) high-risk neuroblastoma trial (HR-NBL1). _J. Clin.

Oncol._ 39, 3377–3390 (2021). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Fischer, M. et al. Ceritinib in paediatric patients with anaplastic lymphoma kinase-positive

malignancies: an open-label, multicentre, phase 1, dose-escalation and dose-expansion study. _Lancet Oncol._ 22, 1764–1776 (2021). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Grissenberger, S.

et al. High-content drug screening in zebrafish xenografts reveals high efficacy of dual MCL-1/BCL-X(L) inhibition against Ewing sarcoma. _Cancer Lett._ 554, 216028 (2023). Article CAS

PubMed Google Scholar * Ambati, S. R. et al. Pre-clinical efficacy of PU-H71, a novel HSP90 inhibitor, alone and in combination with bortezomib in Ewing sarcoma. _Mol. Oncol._ 8, 323–336

(2014). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Pearson, A. D. J. et al. Second Paediatric Strategy Forum for anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK) inhibition in paediatric malignancies:

ACCELERATE in collaboration with the European Medicines Agency with the participation of the Food and Drug Administration. _Eur. J. Cancer_ 157, 198–213 (2021). Article CAS PubMed Google

Scholar * Mosse, Y. P. et al. Safety and activity of crizotinib for paediatric patients with refractory solid tumours or anaplastic large-cell lymphoma: a Children’s Oncology Group phase 1

consortium study. _Lancet Oncol._ 14, 472–480 (2013). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Berlak, M. et al. Mutations in ALK signaling pathways conferring resistance to

ALK inhibitor treatment lead to collateral vulnerabilities in neuroblastoma cells. _Mol. Cancer_ 21, 126 (2022). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Bresler, S. C. et al.

Differential inhibitor sensitivity of anaplastic lymphoma kinase variants found in neuroblastoma. _Sci. Transl. Med._ 3, 108ra114 (2011). Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar *

Debruyne, D. N. et al. ALK inhibitor resistance in ALK(F1174L)-driven neuroblastoma is associated with AXL activation and induction of EMT. _Oncogene_ 35, 3681–3691 (2016). Article CAS

PubMed Google Scholar * Hamilton, L., Astell, K. R., Velikova, G. & Sieger, D. A. Zebrafish live imaging model reveals differential responses of microglia toward glioblastoma cells in

vivo. _Zebrafish_ 13, 523–534 (2016). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Kruyt, M. C. et al. Application and limitations of chloromethyl-benzamidodialkylcarbocyanine for

tracing cells used in bone Tissue engineering. _Tissue Eng._ 9, 105–115 (2003). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Kimmel, C. B., Ballard, W. W., Kimmel, S. R., Ullmann, B. &

Schilling, T. F. Stages of embryonic development of the zebrafish. _Dev. Dyn._ 203, 253–310 (1995). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Westerfield, M. _The Zebrafish Book. A Guide for

the Laboratory Use of Zebrafish (Danio rerio)_. 4th edition (2000). * Aynaud, M. M. et al. Transcriptional Programs Define Intratumoral Heterogeneity of Ewing Sarcoma at Single-Cell

Resolution. _Cell Rep._ 30, 1767–1779.e1766 (2020). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Stewart, E. et al. Orthotopic patient-derived xenografts of paediatric solid tumours. _Nature_

549, 96–100 (2017). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * von Levetzow, C. et al. Modeling initiation of Ewing sarcoma in human neural crest cells. _PLoS ONE_ 6, e19305

(2011). Article Google Scholar * Distel, M. & Koster, R. W. In vivo time-lapse imaging of zebrafish embryonic development. _CSH Protoc._ 2007, pdb prot4816,

https://doi.org/10.1101/pdb.prot4816 (2007). * Maes, J. et al. Evaluation of 14 organic solvents and carriers for screening applications in zebrafish embryos and larvae. _PLoS ONE_ 7, e43850

(2012). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Van Wijk, R. C. et al. Mechanistic and quantitative understanding of pharmacokinetics in zebrafish larvae through nanoscale

blood sampling and metabolite modeling of paracetamol. _J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther._ 371, 15–24 (2019). Article PubMed Google Scholar * Zajec, Z., Dernovsek, J., Distel, M., Gobec, M. &

Tomasic, T. Optimisation of pyrazolo[1,5-a]pyrimidin-7(4H)-one derivatives as novel Hsp90 C-terminal domain inhibitors against Ewing sarcoma. _Bioorg. Chem._ 131, 106311 (2023). Article CAS

PubMed Google Scholar Download references ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS We would like to thank Karin Mühlbacher for help with cell culture work, Achim Kirsch for help with setting up the high-content

imaging and image analysis and Benjamin Natha for excellent zebrafish care. We thank Heinrich Kovar, Beat Schäfer, Frank Westermann, Eleni Tomazou/ Marcus Tötzl and Nai-Kong Cheung for

providing cell lines (TC32, SKshctrl, SK-N-BE(2)C-H2B-GFP, A673 and SK-N-MM, respectively). This work was supported by the Austrian Research Promotion Agency (FFG) project 7940628 533

(Danio4Can) (M.D.), Alex’s Lemonade Stand Foundation (M.D.), the Vienna Science and Technology Fund (WWTF) project LS18-111 (to S.T.M.), the Slovenian Research Agency (Grant No. P1-0208,

J1-1717) (T.T.), the BMBWF through OeAD grant SI 29/2023 (M.D. and T.T.), a DOC fellowship of the Austrian Academy of Sciences (to S.G.) and donations to St. Anna Kinderkrebsforschung. This

project also received support from European funding H2020-lMI2-JTl-201 5-07 (116064–ITCC P4). Parts of this work were supported by Sanofi or the Comprehensive Cancer Center

Forschungsförderung der Initiative Krebsforschung, MedUni Wien (CCC Grant “PECAZA” 2021 to F.E.). AUTHOR INFORMATION Author notes * These authors contributed equally: C. Sturtzel, S.

Grissenberger. AUTHORS AND AFFILIATIONS * St. Anna Children’s Cancer Research Institute (CCRI), Vienna, Austria C. Sturtzel, S. Grissenberger, P. Bozatzi, E. Scheuringer, A.

Wenninger-Weinzierl, S. Pascoal, V. Gehl, F. Rifatbegovic, S. Taschner-Mandl & M. Distel * Zebrafish Platform Austria for Preclinical Drug Screening (ZANDR), Vienna, Austria C. Sturtzel,

E. Scheuringer, A. Wenninger-Weinzierl & M. Distel * Faculty of Pharmacy, University of Ljubljana, Ljubljana, Slovenia Z. Zajec, J. Dernovšek & T. Tomašič * Christian Doppler

Laboratory for Advanced Polymers for Biomaterials and 3D Printing, TU Wien, Vienna, Austria A. Kutsch, A. Granig & J. Stampfl * Service d’Hématologie & Oncologie Pédiatrique, Timone

Hospital, AP-HM, Marseille, France M. Carre & N. André * Centre de Recherche en Cancérologie de Marseille (CRCM), Aix-Marseille Université, CNRS, Inserm, Institut Paoli Calmettes,

Marseille, France M. Carre & N. André * Department of Neurosurgery, Medical University of Vienna, Vienna, Austria A. Lang, D. Lötsch, F. Erhart & G. Widhalm * Central Nervous System

Tumors Unit, Comprehensive Cancer Center, Medical University of Vienna, Vienna, Austria A. Lang, D. Lötsch, F. Erhart & G. Widhalm * Department of Molecular Oncology, Sanofi Research

Center, Vitry-sur-Seine, France I. Valtingojer & J. Moll * Renon Biotech and Pharma Consulting, Unterinn am Ritten (Bz), Italy J. Moll * Balgrist University Hospital, Faculty of

Medicine, University of Zurich (UZH), Zurich, Switzerland D. Surdez * INSERM U830, Diversity and Plasticity of Childhood Tumors Lab, PSL Research University, SIREDO Oncology Center, Institut

Curie Research Center, Paris, France O. Delattre Authors * C. Sturtzel View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * S. Grissenberger View author

publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * P. Bozatzi View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * E. Scheuringer

View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * A. Wenninger-Weinzierl View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google

Scholar * Z. Zajec View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * J. Dernovšek View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed

Google Scholar * S. Pascoal View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * V. Gehl View author publications You can also search for this author

inPubMed Google Scholar * A. Kutsch View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * A. Granig View author publications You can also search for this

author inPubMed Google Scholar * F. Rifatbegovic View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * M. Carre View author publications You can also search

for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * A. Lang View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * I. Valtingojer View author publications You can also

search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * J. Moll View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * D. Lötsch View author publications You can

also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * F. Erhart View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * G. Widhalm View author publications You

can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * D. Surdez View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * O. Delattre View author

publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * N. André View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * J. Stampfl View

author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * T. Tomašič View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * S.

Taschner-Mandl View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * M. Distel View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google

Scholar CONTRIBUTIONS C.S. and S.G. designed, performed, and analyzed experiments and wrote the manuscript and are co-first authors of the manuscript, P.B. designed, performed, and analyzed

experiments, E.S., S.P., V.G., F.R., and A.W.W. performed and analyzed experiments, Z.Z. and J.D. synthesized Hsp90 inhibitors, A.K., A.G., and J.S. developed 3D-printed inserts and stamps,

N.A., A.L., D.S., F.E., G.W., O.D., P.B., and STM contributed cell lines and patient-derived cells, N.A., F.E., G.W., J.S., I.V., and J.M. secured funding and designed experiments, T.T.,

S.T.M., and M.D. secured funding, conceptualized the project, designed experiments and wrote the manuscript. All authors edited and approved the manuscript. CORRESPONDING AUTHORS

Correspondence to S. Taschner-Mandl or M. Distel. ETHICS DECLARATIONS COMPETING INTERESTS The authors declare no competing interests. ADDITIONAL INFORMATION PUBLISHER’S NOTE Springer Nature

remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION SUPPLEMENTARY FIGURES REPORTING SUMMARY RIGHTS AND

PERMISSIONS OPEN ACCESS This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any

medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The

images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not