Post-click labeling enables highly accurate single cell analyses of glucose uptake ex vivo and in vivo

- Select a language for the TTS:

- UK English Female

- UK English Male

- US English Female

- US English Male

- Australian Female

- Australian Male

- Language selected: (auto detect) - EN

Play all audios:

ABSTRACT Cellular glucose uptake is a key feature reflecting metabolic demand of cells in physiopathological conditions. Fluorophore-conjugated sugar derivatives are widely used for

monitoring glucose transporter (GLUT) activity at the single-cell level, but have limitations in in vivo applications. Here, we develop a click chemistry-based post-labeling method for flow

cytometric measurement of glucose uptake with low background adsorption. This strategy relies on GLUT-mediated uptake of azide-tagged sugars, and subsequent intracellular labeling with a

cell-permeable fluorescent reagent via a copper-free click reaction. Screening a library of azide-substituted monosaccharides, we discover 6-azido-6-deoxy-D-galactose (6AzGal) as a suitable

substrate of GLUTs. 6AzGal displays glucose-like physicochemical properties and reproduces in vivo dynamics similar to 18F-FDG. Combining this method with multi-parametric immunophenotyping,

we demonstrate the ability to precisely resolve metabolically-activated cells with various GLUT activities in ex vivo and in vivo models. Overall, this method provides opportunities to

dissect the heterogenous metabolic landscape in complex tissue environments. SIMILAR CONTENT BEING VIEWED BY OTHERS MULTIPLEXED LECTIN-PAINT SUPER-RESOLUTION MICROSCOPY ENABLES CELL

GLYCOTYPING Article Open access 20 February 2025 IN-SITU PROFILING OF GLYCOSYLATION ON SINGLE CELLS WITH SURFACE PLASMON RESONANCE IMAGING Article Open access 24 January 2025 SINGLE-CELL

IMAGING OF Α AND Β CELL METABOLIC RESPONSE TO GLUCOSE IN LIVING HUMAN LANGERHANS ISLETS Article Open access 12 November 2022 INTRODUCTION Cellular glucose uptake is crucial for physiological

and pathological processes, and mediated by the glucose transporter (GLUT) family1,2. GLUT expression on the cell surface facilitates glucose influx to satisfy energy demand in

metabolically active cells, such as cancer and immune cells. Because cellular metabolism is intrinsically dynamic and heterogenous in tissues, assays to determine glucose transport

activities in individual cells are important and urgently needed3,4,5. Various sugar analogs have been developed to measure glucose uptake6 (Fig. S1). 2-Deoxy-D-glucose (2DG) and its

radiolabeled forms (3H-2DG and 18F-FDG) passing through GLUTs provide a reliable readout in bulk measurements but lack cellular resolution6,7,8,9. To monitor glucose transport at the single

cell level, flow cytometry- and microscopy-based approaches using fluorescent sugar analogs are commonly employed6. However, conjugation of a fluorophore to glucose has undesirable effects

on its properties and interactions with GLUTs4,6,9,10,11,12,13,14. For example, 2NBDG and Cy5.5-2DG (Fig. S1) are fluorescent 2DG derivatives with larger molecular sizes (342 and 1089 Da,

respectively) than glucose (180 Da) and do not properly reproduce natural GLUT-dependent glucose influx, causing non-specific background staining in cells and tissues4,6,9,10,11,12,13,14.

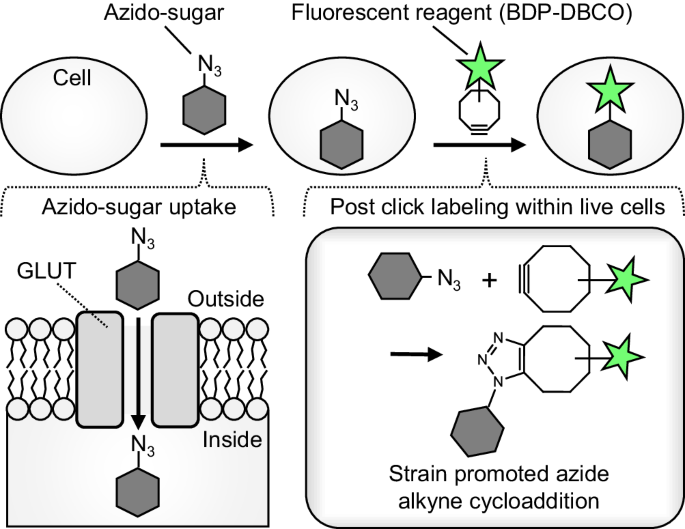

This shortcoming substantially hampers accurate single cell analysis of glucose uptake ex vivo and in vivo. Here, we developed a click chemistry-based post-labeling method for flow

cytometric high-throughput measurement of glucose uptake with minimal perturbation of GLUT activity and low non-specific cellular adsorption. This strategy (Fig. 1) relies on GLUT-mediated

uptake of a clickable azide-tagged sugar, and subsequent intracellular labeling with a cell-permeable fluorescent reagent (BDP-DBCO, Fig. S2a) via a copper-free click reaction15,16. By

screening a library of azide-substituted monosaccharide isomers, we discovered and validated 6-azido-6-deoxy-D-galactose (6AzGal) as a suitable substrate for GLUTs. 6AzGal displays

glucose-like physicochemical properties and reproduces in vivo dynamics similar to 18F-FDG. Combining this method with multi-parametric immunophenotyping, we demonstrated the ability to

precisely resolve metabolically-activated cells with various glucose transport activities in ex vivo and in vivo models. RESULTS DEVELOPMENT OF POST-CLICK LABELING METHOD FOR GLUCOSE UPTAKE

ASSAY Considering that GLUTs are known to import various sugars, including glucose, galactose, and their derivatives6,7,13,14,17, these minimally modified analogs may be recognized as

substrates of GLUTs. A series of monosaccharides with a single azide substitution (Fig. S2b) maintained a low molecular weight (205 Da) comparable with glucose (180 Da) (Fig. 2).

Hydrophilicity of these azido-sugars (evaluated by their cLogP value: −2 to −1) was in a similar range to that of glucose (cLogP: −2) (Fig. 2). Additionally, their physicochemical properties

were almost identical to well-validated non-fluorescent probes 2DG7, 18F-FDG9,14, and 3-OPG13, outperforming the existing fluorescent analogs (Fig. 2 and S1). To measure azido-sugar uptake

(Fig. 1), cells were incubated with azido-sugars, followed by BDP-DBCO treatment and subsequent washing to remove unreacted BDP-DBCO. Of 11 azido-sugars tested by flow cytometry,

6-azido-6-deoxy-D-galactose (6AzGal) produced the highest fluorescence intensity in cellular BDP-DBCO labeling (Figs. 3a, b and S2b, c). The blue-emitting BDP-DBCO variant (8AB-DBCO)16 also

showed fluorescent labeling of 6AzGal-treated cells (Fig. S2d, e). Intense fluorescent signals of BDP-DBCO in 6AzGal-treated cells were predominantly observed in the cytoplasm by confocal

microscopy with minimal fluorescence owing to cell surface glycosylation (Fig. 3c and S2f). Conversely, non-azide-treated cells exhibited much weaker fluorescent signals, representing

efficient removal of unreacted BDP-DBCO, as we reported previously16. Fluorescent labeling after 6AzGal uptake was confirmed in three cell lines (K562, HL60S, and HCC1806) (Figs. 3b, c and

S2g). No significant toxicity was detected by 6AzGal treatment or BDP-DBCO labeling (Fig. S2h). At room temperature, which is standard for the 2DG uptake assay7, a concentration-dependent

linear increase in 6AzGal uptake was observed (Fig. S2i). The uptake kinetics of 6AzGal showed a linear increase at 0–30 min and reached a plateau at 30–60 min (Fig. S2j), which was

consistent with those of 3-OPG reported previously13. Lowering the cellular temperature blocked 6AzGal uptake (Fig. S2k), indicating transporter-dependent 6AzGal influx. To confirm that

6AzGal passed through GLUTs, we conducted the following experiments. A competition assay showed that 6AzGal uptake was dose-dependently suppressed by D-glucose and 2DG, whereas only a

minimal effect was observed using a high concentration of L-glucose, which is not recognized by GLUTs13,14 (Fig. 3d). Cytochalasin B and WZB-117 (endofacial and exofacial GLUT inhibitors,

respectively13,14) blocked 6AzGal uptake (Fig. 3e, f). Efflux from 6AzGal-loaded cells was also reduced by D-glucose and cytochalasin B (Fig. S2l). Using differentiated 3T3-L1 adipocytes, in

which insulin stimulation promotes GLUT4 expression14, 6AzGal uptake was increased in response to insulin (Fig. S2m). These data demonstrated that 6AzGal can act as a substrate of GLUTs. We

further examined the accuracy of this method by comparison with the enzymatic bulk 2DG uptake assay, which is the gold standard to measure glucose transport activity7. Output response upon

2DG uptake in the presence of a GLUT inhibitor was quantitatively evaluated. Cytochalasin B and WZB-117 treatments resulted in potent inhibitory effects on 2DG uptake (>70% signal

reduction) (Fig. S2n), which was almost identical to the corresponding 6AzGal data (Fig. 3e, f). Conversely, a flow cytometric 2NBDG uptake assay showed rather weak effects of both

inhibitors (only 20–40% signal reduction) (Fig. S2o), indicating non-specific cellular binding of 2NBDG as shown in previous reports9,10,11,13,14. These results demonstrated that our method

achieved highly accurate single cell measurements of glucose uptake with low-background adsorption. MEASUREMENT OF 6AZGAL UPTAKE EX VIVO AND IN VIVO BDP-DBCO emitted bright green

fluorescence with minimal overlap in orange-to-red emission (Fig. S3) and can be used for multicolor flow cytometric assays. Additionally, our click labeling of 6AzGal with BDP-DBCO never

needs any other chemicals such as copper which is known to quench commonly used fluorescent proteins [e.g., mCherry and phycoerythrin (PE)]. These features made our method compatible with

multi-parametric phenotyping of tissue-derived cells together with lineage identification. To analyze immune cells ex vivo, leukocytes were prepared from mouse spleens, loaded with 6AzGal,

and stained with surface marker antibodies and a viability dye (FVD), followed by BDP-DBCO treatment (Fig. 4a and S4a). Additional fluorophore-conjugated antibodies (e.g., AF647) and a

cell-tracking dye (CPM) were optionally used for barcoding in multiplexed samples to increase throughput and decrease noise (Fig. S4b, c). The labeled splenocytes were separated into B and T

cell populations by multiple gating (Fig. 4b, left and middle, and S4b). This assay showed that 6AzGal uptake was higher in B cells than in T cells (Fig. 4b, right), which was verified by a

2DG assay (Fig. S4d). Furthermore, upon T cell receptor stimulation, CD4+ T cells expressing activation marker CD69 showed a corresponding increase in 6AzGal uptake (Figs. 4c and S4e–g),

which was consistent with the previous 3H-2DG-based observation of increased GLUT1 activity in metabolically reprogrammed T cells8. Next, we applied this method to in vivo analyses. We

injected 6AzGal into mice intraperitoneally and isolated tissues, followed by multiple labeling similar to ex vivo experiments (Fig. 4a). In all tested tissues (spleen, blood, thymus, and

bone marrow), fluorescent labeling signals were stronger after 6AzGal treatment compared with the no azide control (Figs. 4d and S5a), indicating that 6AzGal underwent widespread diffusion

inside the body, followed by cellular uptake sufficient for flow cytometric detection. The labeling levels in splenocytes strictly depended on the 6AzGal concentration (Fig. S5b) and reached

a peak at 30 min after 6AzGal injection, followed by a steady decline (Fig. S5c). Our observations of the in vivo 6AzGal distribution and kinetics agreed with previous 18F-FDG PET imaging

studies in live mice18. Noticeably, splenic B and T cells loaded with 6AzGal in vivo showed labeling patterns (Figs. 4e and S5d) similar to the corresponding ex vivo data of 6AzGal and 2DG

(Figs. 4b and S4d). Additionally, D-glucose supplementation14 significantly reduced the labeling level in vivo (Fig. 4f), which was consistent with the in vitro competition assay (Fig. 3d).

Lastly, three disease-associated mouse models were analyzed. In response to lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-induced inflammation, which is well known to increase glucose uptake in activated

leukocytes19, splenic B and T cells displayed higher 6AzGal uptake than the no LPS control (Figs. 4g and S6a, S6b). In brain immune cells isolated from mice with ischemic stroke injury,

which activates a cascade of inflammatory processes20, we observed increases in subpopulations with high 6AzGal uptake (Fig. S6c, d). Furthermore, in K562 tumor xenografts, co-injection of

6AzGal with the GLUT inhibitor14 significantly reduced the uptake signal in cancer cells (Fig. 4h and S6e), as observed in the in vitro GLUT specificity test (Fig. 3e). Overall, these

results demonstrated that this method can reliably measure glucose uptake in vitro, ex vivo, and in vivo, and highlighted its robust utility in pathological and pharmacological

investigations. DISCUSSION We described a post-labeling method for quantitative analysis of glucose uptake with single cell resolution. This technique provided a fluorescence signal output

which was proportional to the amount of BDP-DBCO-labeled azido-sugars inside the individual cell. We found that 6AzGal which possesses an azido group at the C-6 position produced the robust

signal reflecting the GLUT activity (Figs. 3 and 4), which agrees with previous studies showing that substitution at the C-6 hydroxyl group with a hydrophobic group enhances the recognition

of the galactose analogs by GLUTs6,21,22. Given that GLUT1 is reported to be the major pathway for glucose transport in HCC1806 cells23, our inhibition assays (Fig. 3f) indicated that 6AzGal

was transported into cells through GLUT1, which is consistent with the fact17 that galactose acts as a substrate of GLUT1. Considering on sugar concentration in culture medium (~25 mM) and

low affinity of GLUT1 for sugar substrates (_K__m_ in the mM range)13, our standard incubation condition (10 mM 6AzGal for 1 hour at room temperature) can produce an intracellular 6AzGal

concentration in the mM range. Based on our previous estimation of labeling reagents accumulated inside cells15, 100 nM BDP-DBCO in medium would give the intracellular concentration of high

μM to sub mM, ensuring strain-promoted alkyne-azide cycloaddition (SPAAC) between BDP-DBCO and 6AzGal inside cells (Fig. 1). In addition, 6AzGal has the primary azide at the less crowed C-6

position which can accelerates the click labeling reaction with BDP-DBCO (Fig. 3a and S2c)21. Since we previously identified BDP-DBCO as the most sensitive probe for organelle-selective

labeling of azide-tagged phosphatidylcholine (PC)16, we chose BDP-DBCO in this work and detected most of the BDP-DBCO-labeled 6AzGal in the endoplasmic reticulum and the Golgi apparatus

(Fig. 3c). This observation together with our previous PC imaging analysis15 raised an interesting possibility of tracing intracellular azido-sugar dynamics in live cells, while 6AzGal

underwent changes in its physicochemical properties upon BDP-DBCO labeling (MW: from 205.2 to 755.6, cLogP: from −0.78 to 2.5). Although the scope of this work was focused on validating flow

cytometric 6AzGal uptake assay, other DBCO reagents16 such as mitochondria-targeting Cy3-DBCO might have a potential to expand organelle-selective azido-sugar labeling. Unlike glucose-based

probes (e.g., 2NBDG, 3H-2DG, 18F-FDG) (Fig. S1), 6AzGal has the 6-deoxygalactose backbone (Fig. 2a) which is not phosphorylated at the 6-position by hexokinase24. Galactokinase

phosphorylates natural galactose at the 1-position, but cannot recognize 6AzGal as a suitable substrate25,26,27. Consistent with these findings, our efflux data (Fig. S2l) suggest that

6AzGal taken up by cells is not phosphorylated and eventually exported out of the cells. Given that the hexokinase-dependent phosphorylation is critical for intracellular accumulation of

glucose-based probes28,29 but not for that of 6AzGal, it is reasonable that an uptake signal of 6AzGal does not perfectly match those of glucose-based probes. Also, different biological

situations (e.g., in vivo vs. ex vivo or fasting vs. non-fasting) may have impacts on the insufficient matching (please see Peer Review File for detail). The more in-depth in vivo studies

may be required to explore this point using a combination of 6AzGal-based flow cytometry and 18F-FDG-based PET imaging/gamma emission recording9,30. This method enables a simple

low-background glucose uptake assay in single cells with high accuracy comparable with the well-established bulk 2DG technique. Our method fully meets the increasing need for rapid,

sensitive, and high-throughput measurements of cellular glucose transport activities ex vivo and in vivo by conventional flow cytometry3,4, and thus substantially expands the scope of single

cell biology, especially in immunometabolism and cancer fields. Our method allows multicolor, live single cell phenotyping, which makes it compatible with various applications such as

lineage identification, cell sorting, RNA-seq, and CRISPR screens. With the potential to combine omics technologies5, our method will be beneficial to dissect the heterogenous metabolic

landscape in complex tissue environments. METHODS CHEMICAL REAGENTS AND ANTIBODIES All chemical reagents from commercial suppliers were used without any further purification:

1-azido-1-deoxy-β-D-glucopyranoside (1AzGlc; Sigma, 514004), 2-azido-2-deoxy-D-glucose (2AzGlc; Sigma, 712795), 3-azido-3-deoxy-D-glucopyranose (3AzGlc; synthose, AG915),

4-azido-4-deoxy-D-glucose (4AzGlc; synthose, AG397), 6-azido-6-deoxy-D-glucose (6AzGlc; Sigma, 712760), 1-azido-1-deoxy-β-D-galactopyranoside (1AzGal; Sigma, 513989),

2-azido-2-deoxy-D-galactose (2AzGal, Biosynth, MA03562), 4-azido-4-deoxy-D-galactose (4AzGal, synthose, AL788), 6-azido-6-deoxygalactose (6AzGal; Sigma, 712752), α-D-mannopyranosyl azide

(1AzMan; synthose, MM947), 6-azido-L-fucose (6AzFuc; synthase, AF415), 2-deoxy-D-glucose (2DG; TCI, D0051), 2NBDG (Wako, 334-00631), D-glucose (Wako, 043-31163), L-glucose (Wako, 599-20963),

cytochalasin B (Wako, 030-17551), WZB-117 (Sigma, SML0621), 7-diethylamino-3-(4-maleimidophenyl)-4-methylcoumarin (CPM; Wako, 045-29131), BDP FL DBCO (BDP-DBCO; BroadPharm, BP-23473), and

eBioscience™ Fixable Viability Dye eFluor™ 780 (FVD780; Invitrogen, 65-0865-14). Following fluorophore-conjugated monoclonal antibodies were used for flow cytometry (1:100 dilution):

CD19-PE/Cy7 (BioLegend, 115519), CD3e-BV421 (BioLegend, 100335), CD3e-BV711 (BioLegend, 100349), CD4-PE/Cy7 (BioLegend, 100527), CD4-PE/Dazzle594 (BioLegend, 100565), CD8a-SVB515 (BioRAD,

MCA609SBV515), CD69-BV421 (BioLegend, 104527), CD45-AF647 (BioLegend, 103123), CD45-BV421 (BioLegend, 103133), CD11b-BV421 (BioLegend, 101235). ANIMALS C57BL/6 J mice (6–8 weeks, female) and

BALB/c Slc-nu mice (6–8 weeks, female) were purchased from Japan SLC, Inc. C.B-17/Icr-scid/scidJcl mice (6–8 weeks, male) with surgically induced ischemic stroke were purchased from Clea

Japan, Inc. All animal husbandry and experimental procedures were approved by the Animal Care Use and Review Committee of Kyoto University. We have complied with all relevant ethical

regulations for animal use. For ex vivo and in vivo studies, C57BL/6 mice were used unless otherwise indicated. BALB/c mice were only used for tumor xenograft experiments. C.B-17 mice were

only used for brain cell isolation. CELL CULTURES K562 (Riken BRC, RCB0027), HL60S (JCRB cell bank, JCRB0163) and HCC1806 (ATCC, CRL-2335) cells were grown in IMDM (Wako, 098-06465)

containing 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Nichirei, 174012) and 1× penicillin-streptomycin solution (P/S; Wako, 168-23191) (hereafter GM). 3T3-L1 MBX (ATCC, CRL-3242) cells were cultured in

DMEM (Wako, 043-30085) containing 10% FBS and 1× P/S. K562 cells were used in all assays. mCherry-expressing K562 cells were generated by infecting K562 cells with mCherry-expressing

lentivirus16, and only used for tumor xenografting. To induce adipocyte differentiation, 3T3-L1 MBX cells were seeded on 35 mm glass-base dish (IWAKI, 3971-035), and cultured for 48–72 hours

to reach confluency. Cells were cultured in differentiation medium I (DMEM, 10% FBS, 1× P/S, 0.5 mM IBMX, 1 μg/mL insulin, 0.25 μM dexamethasone, and 2 μM rosiglitazone) for 48 hours,

differentiation medium II (DMEM, 10% FBS, 1× P/S, and 1 μg/mL insulin) for 48 hours, and 10% FBS-containing DMEM for 48 hours. AZIDO-SUGAR UPTAKE IN LIVING CELLS AND POST-CLICK LABELING

Prior to azido-sugar incorporation, cell density was adjusted. For suspension cell lines or primary cells, density was adjusted to 1 × 106 cells/mL. For adherent cell lines, 3 × 105 HCC1806

cells were seeded on a 35 mm glass bottom dish, and cultured for 20–24 h. Differentiated 3T3-L1 cells were prepared as described above. Cells were then washed with glucose-free IMDM [Gmep,

custom-made: glucose was removed from the original IMDM (Wako, 098-06465)] twice, and incubated in glucose-free IMDM containing 10 mM azido-sugar at 25 °C for 60 mins, unless otherwise

indicated. For overnight incubation in viability assays, cells were cultured in glucose-free IMDM supplemented with 20 μg/mL insulin, 110 μg/mL apo-transferrin, 13.4 ng/mL sodium selenite, 1

μg/mL L-ascorbic acid-2-phosphate at 37 °C for 20–24 h. After azido-sugar incorporation, cells were washed with 4% FBS/IMDM, and subsequently incubated with 100 nM BDP-DBCO diluted in 4%

FBS/IMDM at 25 °C for 15 mins. Then, cells were washed with GM twice, and resuspended with GM for flow cytometry or microscopy. To examine the effect of GLUT1 inhibitors (cytochalasin B and

WZB-117) and competitive inhibitors (D-glucose, L-glucose, and 2DG), cells were washed with glucose-free IMDM twice, then pre-incubated with 1- or 10-μM GLUT1 inhibitors or 10- or 50-mM

competitive inhibitors for 1 hr at 25 °C, followed by addition of 10 mM 6AzGal and labeling as described above. To examine the efflux of 6AzGal, cells treated with 6AzGal as described above

were incubated in glucose-free IMDM, IMDM, or IMDM with 10 μM cytochalasin B at 25 °C for up to 120 mins, and labeled as described above. FLOW CYTOMETRY Cells were filtered and transferred

into a 5 ml tube with cell strainer (35 μm pore size). The flow cytometry was performed using Sony Cell Sorter MA900, equipped with four excitation lasers (488, 405, 561, and 638 nm) and

12-color channels. All four lasers and filters with emission BP 525/50, 785/60, 450/50, 665/30, and 720/60 were used in this study. For optimal data acquisition, 100 μm sorting chips and

following instrument settings were used for each cell types: K562: FSC threshold value: 5%; Sensor gain: FSC: 3, BSC: 33.5%, 525/50: 28.5%, and 665/30: 36.5%. HL60S: FSC threshold value: 5%;

Sensor gain: FSC: 5, BSC: 36.0%, 525/50: 37.0%. Cells derived from spleen, thymus, blood, bone marrow, and brain tissues: FSC threshold value: 17%; Sensor gain: FSC: 11, BSC: 43.0%, 525/50:

43.5%, 785/60: 48.5%, 450/50: 45.0%, 665/30: 45.0%, and 720/60: 48.0%. For each sample, at least 30,000 events were analyzed. The data acquisition, analysis, and image preparation were

carried out using the instrument software MA900 Cell Sorter Software (Sony). To conduct multi-color analysis with BDP-DBCO, fluorophores with a relative fluorescence intensity lower than 1%

in the FL1 channel (BP 525/50) were used (Fig. S3). CONFOCAL MICROSCOPY To observe 6AzGal distribution in live K562 cell, 50 μL of cells labeled as described above was deposited on a 35 mm

glass-base dish, allowed to settle on the bottom of the dish for 5 mins. HCC1806 and differentiated 3T3-L1 MBX cells cultured in a 35 mm glass-base dish were labeled as described above.

Microscopy was performed using a Zeiss LSM800 confocal microscope with a Zeiss Plan-Apochromat ×63/1.40 oil objective. The data acquisition, analysis, and image preparation were carried out

using the instrument software ZEN (ZEISS). 2DG AND 2NBDG UPTAKE ASSAYS For measuring 2DG uptake, Glucose Uptake-Glo Assay (Promega, J1341) was performed as manufacturer’s instruction.

Briefly, cells were rinsed with glucose-free IMDM twice, then 50 μL of 1 × 105 K562 cells was seeded per well of a white 96-well plate. Cells were then incubated with 1 mM 2DG at 25 °C for 1

hour, and followed by subsequently adding stop buffer, neutralization buffer, and detection buffer. Luminescence was measured with a plate reader (TECAN, Infinite® 200 PRO). For measuring

2NBDG uptake, K562 cells were pre-washed with glucose-free IMDM, incubated with 300 μM 2NBDG at 37 °C for 30 mins14, then washed with GM twice, and subjected to flow cytometric analysis. To

examine the effect of GLUT1 inhibitors on 2DG/2NBDG uptake, cells were pre-treated with GLUT1 inhibitor as described above, prior to the 2DG/2NBDG incubation. For 2DG uptake assay on

purified splenic T and B cells, cells were first isolated with EasySepTM Mouse T cell Isolation kit (StemCellTM, 19851) and EasySepTM Mouse B cell Isolation kit (StemCellTM, 19854) as

manufacturer’s instruction respectively, followed by Glucose Uptake-Glo Assay. CELL VIABILITY ASSAYS After K562 cells were treated with 6AzGal and labeled with BDP-DBCO as described above,

following cell assays were conducted. For trypan blue assay, 50 μL of cell suspension was mixed with equal volume of 0.4% (v/v) trypan blue solution, and then cell numbers were counted with

Automated Cell Counter (ThermoFisher). For propidium iodide (PI)/annexin V-Alexa Fluor 488 apoptosis detection assay (ThermoFisher, A13201), 200 μL of cell suspension was transferred to 1.5

mL tube, mixed with 1 μL each stock solution of PI and annexin V, incubated at 25 °C for 15 mins, then analyzed with flow cytometry. For Cell Counting Kit-8 (CCK8) assay (Wako, 341-07761),

100 μL of cell suspension was inoculated on a 96-well plate per well. 10 μL of CCK8 stock solution was added into each well and incubated at 37 °C for 1 hour. The absorbance at 450 nm was

measured with a plate reader. EX VIVO 6AZGAL UPTAKE ASSAYS For analysis of splenocytes, mice were euthanized by cervical dislocation, and spleen was harvested according to the previous

protocol31. The tissue was placed on 70 μm cell strainer inserted on top of the 50 ml conical tube, moistened with 2% FBS/PBS, then dilacerated with the plunger of a 3 ml syringe, followed

by centrifugation at 450 × _g_ for 7 mins to pellet the splenic cells. Cells were resuspended with 1 mL of VersaLyse solution (Beckman, A09777), and incubated at 25 °C for 15 mins. After the

erythrocyte lysing step, 5 mL of 2% FBS/PBS was added and centrifuged at 450 × _g_, 7 mins, then resuspended with glucose-free IMDM or GM to 2–5 × 106 cells/mL. 6AzGal incorporation was

performed as described above, followed by immunolabelling with fluorescence-conjugated antibodies in the presence of FVD780 in GM at 25 °C for 15 mins, washed with 4% FBS/IMDM twice, then

labeled with BDP-DBCO and subjected to flow cytometric analysis as described above. For analysis of CD3/CD28-stimulated T cells, T cells were purified from a splenic suspension with

EasySepTM Mouse T cell Isolation kit as manufacturer’s instruction. Purified splenic T cells were resuspended in GM at a cell density of 1 × 106 cells/mL, then 2 × 106 cells (2 mL) were

dispatched in each well of a six-well plate. To activate T cells, 20 μL of Dynabeads Mouse T-activator CD3/CD28 (ThermoFisher, 11456D) was added into the well, and cultured at 37 °C for 48

hours. Stimulated and non-stimulated cells were then collected, followed by 6AzGal incorporation, immunolabeling, BDP-DBCO labeling as described above, and finally analyzed with flow

cytometry. IN VIVO 6AZGAL UPTAKE ASSAYS Twenty mg/kg of 6AzGal was administered intraperitoneally (for spleen, thymus, blood, and bone marrow) or retro-orbitally (brain) into fasted mice and

circulated for 30 mins, or otherwise indicated. After the mice were sacrificed, tissues of the interest were collected and processed as follows. Spleen and thymus were subjected to

preparation of single cell suspension as described above in the ex vivo 6AzGal uptake assays in splenocytes. Whole blood was collected by cardiac puncture in heparin tubes and treated with

VersaLyse solution to lyse erythrocytes as the manufacturer’s instruction. White blood cells were obtained by centrifugal separation. Bone marrow-derived cells were collected by flushing the

femur and tibia bone marrow with PBS according to the previous protocol32. For brain cell purification, isolation of myelin-free brain cells was performed according to the previous

protocol33 with modification. Briefly, after removal of olfactory bulbs, midbrain, cerebellum and hindbrain, remaining forebrain was minced into smaller pieces with a surgical blade. Tissues

were treated with 2 mg/mL collagenase (Wako, 038-22361), 28 U/mL DNase I (NipponGene, 314-08071), 5% FBS, 10 μM HEPES (Wako, 345-06681) in 1× PBS (Mg2+/Ca2+-free) at 37 °C for 30 mins, then

dissociated with 1000 μL pipet tip, and filtered through 70 μm cell strainer to remove debris and undissociated cell clusters, followed by 30%/70% Percoll gradient to remove myelin and red

blood cells. Purified cells were then immunolabelled with fluorescent-tagged antibodies for 15 mins at 25 °C in GM, followed by BDP-DBCO labeling and flowcytometric analysis. For accurate

measurements, 10 μM cytochalasin B was constantly supplied to prevent efflux of 6AzGal. To determine the effect of lipopolysaccharide (LPS; Wako, 125-05181) on 6AzGal uptake in vivo, 50

mg/kg of LPS was intraperitoneally administrated, and allowed to be absorbed and circulated for 4 hours prior to 6AzGal administration. To determine the inhibitory effect of D-glucose on

6AzGal uptake in vivo, 8 mg/kg of 6AzGal were intraperitoneally injected with or without 12 mg/kg of D-glucose. SUBCUTANEOUS TUMOR XENOGRAFT Stable mCherry-expressing K562 cells were

harvested, washed twice in PBS and resuspended in IMDM at density of 1 × 107 cells/mL. One million cells were inoculated subcutaneously into the dorsal side of the nude mice. Xenografts were

then grown for 2–3 weeks. After tumor became visibly obvious (1.5 cm × 1 cm × 0.5 cm at least), xenografted mice were injected i.p. with 10 mg/kg of WZB-117 (ref. 14) 1 hour before

administration of 6AzGal. Xenograft tumors were harvested and placed on 70 μm cell strainer inserted on top of the 50 ml conical tube, moistened with 2% FBS/PBS, then dilacerated with the

plunger of a 3 ml syringe, followed by centrifugation at 450 × _g_ for 7 mins to pellet the splenic cells. Cells were resuspended with 1 mL VersaLyse Buffer, and incubated at 25 °C for 15

mins. After the erythrocyte lysing step, 5 mL of 2% FBS/PBS was added and centrifuged at 450 × _g_, 7 mins, then resuspended with glucose-free IMDM or GM to 2–5 × 106 cells/mL. Cells were

then labeled and analyzed as described above. STATISTICS AND REPRODUCIBILITY All data were represented as mean ± SEM. Statistical analyses were performed using a two-way unpaired _t_ test.

Sample sizes were included in figures or legends. For flow cytometric assays, the sample sizes indicate numbers of independent cell culture (Figs. 3d, e, S2c, h–l, n, o) and individual mice

(Figs. 4b, e–h and S4d, g, S5b, c, S6d). For confocal imaging, the sample sizes indicate numbers of individual cells (Figs. 3f and S2m). All the experiments were repeated at least three

times. Linear fitting and the corresponding _R_2 values (Figs. 4c and S2i, j, S5b) were obtained using Microsoft Excel (detailed data and calculation were present in Source Data file).

REPORTING SUMMARY Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article. DATA AVAILABILITY All data that support the findings

are available within the manuscript and the Supplementary Information. Numerical source data for the graphs in the manuscript are available in Supplementary Data 1. Other data supporting

this study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable requests. REFERENCES * Hay, N. Reprogramming glucose metabolism in cancer: Can it be exploited for cancer therapy? _Nat.

Rev. Cancer_ 16, 635–649 (2016). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * O’Neill, L. A. J., Kishton, R. J. & Rathmell, J. A guide to immunometabolism for immunologists.

_Nat. Rev. Immunol._ 16, 553–565 (2016). Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Artyomov, M. N. & Van den Bossche, J. Immunometabolism in the single-cell era. _Cell Metab._

32, 710–725 (2020). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Voss, K. et al. A guide to interrogating immunometabolism. _Nat. Rev. Immunol._ 21, 637–652 (2021). Article CAS

PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Baysoy, A., Bai, Z., Satija, R. & Fan, R. The technological landscape and applications of single-cell multi-omics. _Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol._

24, 695–713 (2023). * Kim, W. H., Lee, J., Jung, D. W. & Williams, D. R. Visualizing sweetness: Increasingly diverse applications for fluorescent-tagged glucose bioprobes and their

recent structural modifications. _Sensors_ 12, 5005–5027 (2012). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Valley, M. P. et al. A bioluminescent assay for measuring glucose

uptake. _Anal. Biochem._ 505, 43–50 (2016). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Macintyre, A. N. et al. The glucose transporter Glut1 is selectively essential for CD4 T cell activation

and effector function. _Cell Metab._ 20, 61–72 (2014). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Reinfeld, B. I. et al. Cell-programmed nutrient partitioning in the tumour

microenvironment. _Nature_ 593, 282–288 (2021). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Watson, M. L. J. et al. Metabolic support of tumour-infiltrating regulatory T cells by

lactic acid. _Nature_ 591, 645–651 (2021). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Sinclair, L. V., Barthelemy, C. & Cantrell, D. A. Single cell glucose uptake assays: a

cautionary tale. _Immunometabolism_ 2, e200029 (2020). Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Cheng, Z. et al. Near-infrared fluorescent deoxyglucose analogue for tumor optical

imaging in cell culture and living mice. _Bioconjug. Chem._ 17, 662–669 (2006). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Hu, F. et al. Vibrational imaging of glucose uptake

activity in live cells and tissues by stimulated raman scattering. _Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl._ 54, 9821–9825 (2015). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Maric, T. et

al. Bioluminescent-based imaging and quantification of glucose uptake in vivo. _Nat. Methods_ 16, 526–532 (2019). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Tamura, T. et al.

Organelle membrane-specific chemical labeling and dynamic imaging in living cells. _Nat. Chem. Biol._ 16, 1361–1367 (2020). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Tsuchiya, M., Tachibana,

N., Nagao, K., Tamura, T. & Hamachi, I. Organelle-selective click labeling coupled with flow cytometry allows pooled CRISPR screening of genes involved in phosphatidylcholine metabolism.

_Cell Metab._ 35, 1072–1083.e9 (2023). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Burant, C. F. & Bell, G. I. Mammalian facilitative glucose transporters: evidence for similar substrate

recognition sites in functionally monomeric proteins. _Biochemistry_ 31, 10414–10420 (1992). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Wong, K. P., Sha, W., Zhang, X. & Huang, S. C.

Effects of administration route, dietary condition, and blood glucose level on kinetics and uptake of 18F-FDG in mice. _J. Nucl. Med._ 52, 800–807 (2011). Article PubMed Google Scholar *

Seemann, S., Zohles, F. & Lupp, A. Comprehensive comparison of three different animal models for systemic inflammation. _J. Biomed. Sci._ 24, 60 (2017). Article PubMed PubMed Central

Google Scholar * Iadecola, C., Buckwalter, M. S. & Anrather, J. Immune responses to stroke: mechanisms, modulation, and therapeutic potential. _J. Clin. Investig._ 130, 2777–2788

(2020). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Svatunek, D., Houszka, N., Hamlin, T. A., Bickelhaupt, F. M. & Mikula, H. Chemoselectivity of tertiary azides in

strain-promoted alkyne-azide cycloadditions. _Chem. - A Eur. J._ 25, 754–758 (2019). Article CAS Google Scholar * Liu, X. et al. Fluorescent 6-amino-6-deoxyglycoconjugates for glucose

transporter mediated bioimaging. _Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun._ 480, 341–347 (2016). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Wu, Q. et al. GLUT1 inhibition blocks growth of RB1-positive

triple negative breast cancer. _Nat. Commun._ 11, 4205 (2020). Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Wilson, J. E. Isozymes of mammalian hexokinase: Structure, subcellular

localization and metabolic function. _J. Exp. Biol._ 206, 2049–2057 (2003). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Daughtry, J. L., Cao, W., Ye, J. & Baskin, J. M. Clickable galactose

analogues for imaging glycans in developing zebrafish. _ACS Chem. Biol._ 15, 318–324 (2020). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * McAuley, M., Kristiansson, H., Huang, M., Pey, A. L.

& Timson, D. J. Galactokinase promiscuity: a question of flexibility? _Biochem. Soc. Trans._ 44, 116–122 (2016). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Thoden, J. B., Timson, D. J.,

Reece, R. J. & Holden, H. M. Molecular structure of human galactokinase: Implications for type II galactosemia. _J. Biol. Chem._ 280, 9662–9670 (2005). Article CAS PubMed Google

Scholar * Pajak, B. et al. 2-Deoxy-D-glucose and its analogs: from diagnostic to therapeutic agents. _Int. J. Mol. Sci._ 21, 234 (2020). Article CAS Google Scholar * O’Neil, R. G., Wu,

L. & Mullani, N. Uptake of a fluorescent deoxyglucose analog (2-NBDG) in tumor cells. _Mol. Imaging Biol._ 7, 388–392 (2005). Article PubMed Google Scholar * Xiang, X. et al.

Microglial activation states drive glucose uptake and FDG-PET alterations in neurodegenerative diseases. _Sci. Transl. Med._ 13, eabe5640 (2021). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar *

Grosjean, C. et al. Isolation and enrichment of mouse splenic T cells for ex vivo and in vivo T cell receptor stimulation assays. _STAR Protoc._ 2, 100961 (2021). Article CAS PubMed

PubMed Central Google Scholar * Toda, G., Yamauchi, T., Kadowaki, T. & Ueki, K. Preparation and culture of bone marrow-derived macrophages from mice for functional analysis. _STAR

Protoc._ 2, 100246 (2021). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Bordt, E. A. et al. Isolation of microglia from mouse or human tissue. _STAR Protoc._ 1, 100035 (2020). Article PubMed

PubMed Central Google Scholar Download references ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS We thank Mitchell Arico from Edanz (https://jp.edanz.com/ac) for editing a draft of this manuscript. This work was

supported by a Grant-in-Aid for Specially Promoted Research (JSPS KAKENHI Grant 23H05405) and the Japan Science and Technology Agency (JST) ERATO Grant JPMJER1802 to I.H., and a Grant-in-Aid

for Early-Career Scientists (22K15060), a Grant-in-Aid for Transformative Research Areas (23H03856), JST PRESTO Grant JPMJPR20EA, the Terumo Life Science Foundation and the Japan Health

Foundation to M.T. AUTHOR INFORMATION AUTHORS AND AFFILIATIONS * Department of Synthetic Chemistry and Biological Chemistry, Graduate School of Engineering, Kyoto University, Katsura,

Nishikyo-ku, Kyoto, 615-8510, Japan Masaki Tsuchiya, Nobuhiko Tachibana & Itaru Hamachi * PRESTO (Precursory Research for Embryonic Science and Technology, JST), Sanbancho, Chiyoda-ku,

Tokyo, 102-0075, Japan Masaki Tsuchiya & Nobuhiko Tachibana * School of Pharmaceutical Sciences, University of Shizuoka, 52-1 Yada, Suruga-ku, Shizuoka, 422-8526, Japan Masaki Tsuchiya *

ERATO (Exploratory Research for Advanced Technology, JST), Sanbancho, Chiyoda-ku, Tokyo, 102-0075, Japan Itaru Hamachi Authors * Masaki Tsuchiya View author publications You can also search

for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Nobuhiko Tachibana View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Itaru Hamachi View author publications

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar CONTRIBUTIONS M.T. and I.H. conceived the project and designed the experiments. M.T. and N.T. performed the experiments and data

analysis. M.T., N.T. and I.H. wrote the manuscript with input from all authors. CORRESPONDING AUTHOR Correspondence to Itaru Hamachi. ETHICS DECLARATIONS COMPETING INTERESTS The authors

declare no competing interests. PEER REVIEW PEER REVIEW INFORMATION _Communications Biology_ thanks Seung Bum Park and Linda Sinclair for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Primary Handling Editor: David Favero. A peer review file is available. ADDITIONAL INFORMATION PUBLISHER’S NOTE Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in

published maps and institutional affiliations. SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION PEER REVIEW FILE SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION DESCRIPTION OF ADDITIONAL SUPPLEMENTARY FILES SUPPLEMENTARY DATA 1

REPORTING SUMMARY RIGHTS AND PERMISSIONS OPEN ACCESS This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation,

distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and

indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to

the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will

need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. Reprints and permissions ABOUT THIS ARTICLE

CITE THIS ARTICLE Tsuchiya, M., Tachibana, N. & Hamachi, I. Post-click labeling enables highly accurate single cell analyses of glucose uptake ex vivo and in vivo. _Commun Biol_ 7, 459

(2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s42003-024-06164-y Download citation * Received: 11 August 2023 * Accepted: 08 April 2024 * Published: 16 April 2024 * DOI:

https://doi.org/10.1038/s42003-024-06164-y SHARE THIS ARTICLE Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content: Get shareable link Sorry, a shareable link is not

currently available for this article. Copy to clipboard Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative