GWAS meta-analysis reveals key risk loci in essential tremor pathogenesis

- Select a language for the TTS:

- UK English Female

- UK English Male

- US English Female

- US English Male

- Australian Female

- Australian Male

- Language selected: (auto detect) - EN

Play all audios:

Essential tremor (ET) is a prevalent neurological disorder with a largely unknown underlying biology. In this genome-wide association study meta-analysis, comprising 16,480 ET cases and

1,936,173 controls from seven datasets, we identify 12 sequence variants at 11 loci. Evaluating mRNA expression, splicing, plasma protein levels, and coding effects, we highlight seven

putative causal genes at these loci, including CA3 and CPLX1. CA3 encodes Carbonic Anhydrase III and carbonic anhydrase inhibitors have been shown to decrease tremors. CPLX1, encoding

Complexin-1, regulates neurotransmitter release. Through gene-set enrichment analysis, we identify a significant association with specific cell types, including dopaminergic and GABAergic

neurons, as well as biological processes like Rho GTPase signaling. Genetic correlation analyses reveals a positive association between ET and Parkinson’s disease, depression, and

anxiety-related phenotypes. This research uncovers risk loci, enhancing our knowledge of the complex genetics of this common but poorly understood disorder, and highlights CA3 and CPLX1 as

potential therapeutic targets.

Essential tremor (ET) is one of the most common neurological disorders, affecting up to 5% of the population1. However, epidemiological studies show that the prevalence of the disorder is

considerably underestimated as mildly affected individuals may not seek medical care2.

ET is an isolated syndrome of bilateral upper limb postural or kinetic tremor, that may be with or without tremor of head, voice, or lower limbs and without other neurological signs such as

dystonia, ataxia, or parkinsonism3. Although not life-threatening, the disorder can severely impact daily activities, reducing quality of life. Increasing age, European descent4,5,6 and

family history7,8 are considered risk factors for ET.

Diagnosing ET can be challenging and often requires subspecialty consultation with a movement disorders neurologist. The diagnosis involves reviewing medical and family history and

conducting a thorough neurological examination, as a biomarker or diagnostic test is not available9. Although there is no cure for ET, several treatment options are available to ease the

symptoms. These include drug therapy (beta blockers, anti-epileptics, and tranquilizers), deep brain stimulation, and lifestyle modifications, such as avoiding triggers that can increase the

severity of the tremors.

The cause of ET is not fully understood, but there is a growing support for the etiology of ET being partly related to abnormalities of the cerebello-thalamo-cortical network, including loss

of Purkinje cells and reduced γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA) receptor expression in the dentate nucleus10,11.

Previously, the largest genome-wide association study (GWAS) meta-analysis of ET reported five risk loci using data from 7177 cases and 475,877 controls from European populations12. Here, we

more than double the ET case number, combining 16,480 cases and 1,936,173 controls in a GWAS meta-analysis and find 12 independent sequence variants at 11 loci, of which 8 are novel. Our

research presents new genetic revelation regarding GABAergic dysfunction in ET, highlights the role of dopaminergic neurons, and provides further insight into the genetics of ET, offering

clues that may lead to novel future treatment options.

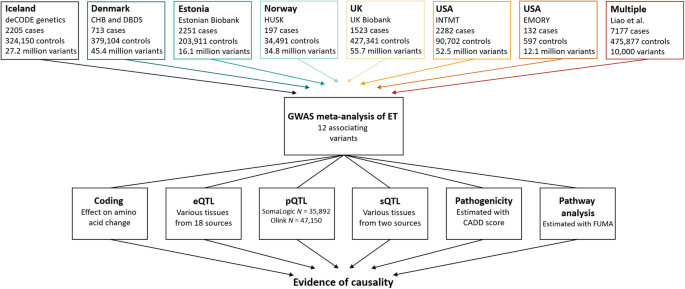

In a meta-analysis of ET, we combined GWAS results from Iceland, Denmark, Estonia, Norway, UK, and USA (seven datasets) with summary statistics from a reported GWAS12, resulting in 16,480

cases and 1,936,173 controls (Fig. 1 and Supplementary Data 1). Using a fixed-effect inverse variance model, we tested for association, under an additive model, between ET and sequence

variants with imputation information over 0.8 and minor allele frequency (MAF) over 0.01% in each dataset (except the Estonian dataset and the reported GWAS, where variants with MAF over 1%

were included). To account for multiple testing, we used weighted genome-wide significance thresholds based on the predicted functional impacts of the associated variants (Supplementary Data

2).

The first row lists the datasets used in the GWAS meta-analysis, number of ET cases, controls and variants analyzed. We included variants with MAF > 0.01% in all datasets except for the

Estonian dataset and the previous GWAS12, where variants with MAF > 1% were included. The summary data from a previous GWAS, only includes the top 10,000 variants. The last row lists the

multiomics approaches used to search for potential causal genes. Expression quantitative trait loci (eQTL) data sources are listed in Supplementary Data 15. Plasma protein levels (pQTL) were

measured in Icelandic samples using Somalogic platform and in UK samples using the Olink platform. Splicing quantitative loci (sQTL) data were estimated using Icelandic RNA sequencing data,

in addition to data imported from GTEx.

We uncovered association with ET at 11 loci (Supplementary Fig. 1 and Supplementary Data 3). Conditional analysis revealed a secondary signal at one of the loci (Supplementary Data 4). In

total, we uncovered 12 independent common variants, 8 of which are novel (Fig. 2). There was no evidence of heterogeneity (all P-het > 0.05), indicating consistency of effects across the

datasets (Supplementary Data 3). Five variants have been reported to associate with ET12 and we show supportive evidence for all except one, at chromosome 1p13.1 (Supplementary Data 5). We

report these signals directly or through a correlated variant (r2 ≥ 0.8) at the same locus (Supplementary Data 5). At chromosome 4p15.2, we observed a previously reported variant as the

primary signal, along with a novel variant at the same locus acting as the secondary signal (r2 = 0.022, Supplementary Fig. 1c, f).

The -log10P-values (y-axis) are plotted for each variant against their chromosomal position (x-axis). Variants with P-values below their weighted variant-class threshold are highlighted.

Novel variants are marked in orange and previously reported variants are marked in blue. P-values are two-sided and derived from a likelihood-ratio test. Manhattan plots for each dataset are

shown in Supplementary Fig. 2.

We searched for causal genes at the ET loci by evaluating the affected amino acid sequence of the lead variants and highly correlated variants (r2 ≥ 0.8), mRNA expression (expression

quantitative trait loci [eQTLs]), splicing quantitative loci (sQTLs), and plasma protein levels (pQTLs) (Fig. 1). We found coding variants at three of the ET associated loci, in CA3 (p.V31I,

r2 = 1.00 with lead variant), EHBP1 (p.K720Q/K755Q, r2 = 0.96 with lead variant), and GCKR (p.L446P, lead variant) (Fig. 3 and Supplementary Data 6). We found eQTLs for BACE2, CPLX1, OTX1,

C2orf16, and CA3 (Supplementary Data 7) and pQTLs for CA3 (Supplementary Data 8) and GCKR (Supplementary Data 9).

Using multiomics approaches of the lead 12 variants, we identified 7 potential causal genes. Gray boxes indicate where data points to a candidate causal gene. Effects are shown for the minor

allele. Combined Annotation Dependent Depletion (CADD)84 score estimates the deleteriousness of sequence variants. Variants are considered pathogenic if CADD > 12.37. *Secondary signal at

PPARGC1A.

The lead ET variant at the CA3 locus confers protection against ET (rs955007-C, P = 1.4 × 10−12, OR = 0.92, Fig. 3. and Supplementary Data 3) and is also highly correlated (r2 = 0.97) with

the primary cis-eQTL which decreases CA3 expression in skeletal muscles (rs10088136-A, P = 8.7 × 10−13, β = -0.13, Supplementary Data 7). Using COLOC13, we estimated that the posterior

probability that the ET association and the eQTL are caused by the same variant is 89%. In addition, the lead variant is highly correlated (r2 = 1.00) with the primary pQTL for carbonic

anhydrase III and decreases its plasma levels (chr8:85445533, P = 3.2 × 10−131, β = −0.22, Supplementary Data 8). Furthermore, rs955007-C also associates with lower plasma levels of carbonic

anhydrase XIII (located roughly 200KB upstream, P = 6.3 × 10−195, β = −0.23). However, rs955007 is not in high LD (r2 = 0.14) with the primary pQTL at the region (Supplementary Data 8).

The lead intronic ET variant within EHBP1 is highly correlated (r2 = 0.91) with the top cis-eQTLs for OTX1 in whole blood (rs76298426-C, P = 10−1673, β = 1.15) and neutrophiles

(rs146236066-CT, P = 1.6 × 10−51, β = 0.98, Supplementary Data 7).

We identified an intronic variant in CPLX1 that confers risk of ET (rs13128363-T, P = 9.0 × 10−15, OR = 1.14, Fig. 3 and Supplementary Data 3) and is the top cis-eQTL for the gene in whole

blood (Supplementary Data 7).

Gene-set enrichment analysis in FUMA14 highlighted cell types in the human embryonic midbrain such as dopaminergic neurons, GABAergic neuroblasts and neurons, and mediolateral neuroblast

(Supplementary Data 10). In addition, the analysis revealed enrichment for pathways such as regulation of response to stress, cell adhesion, and Rho GTPase cycles (Supplementary Data 10).

The sex ratio in our study is close to 50% (52.9% females, Supplementary Data 1). When applying sex-specific models to the Icelandic, Danish, Norwegian, UK, and US-INTMT datasets for the 12

ET variants, none of the variants had an effect that significantly differed between the sexes, after accounting for multiple testing (P-het > 0.05/12 = 0.0042, Supplementary Data 11).

A close to complete genealogy exists for the Icelandic dataset. We did not find high-impact variants, including start-lost, stop-gain, stop-lost, splice donor, splice acceptor, or

frameshift, segregating among 53 large families with high incidence of ET (N ≥ 5). In addition, we did not see a significant difference in effects of 11 of the 12 lead variants between

familial (N = 1153) and sporadic cases (P-het > 0.05/12 = 0.0042, Supplementary Fig. 3). Using the 12 independent variants, we estimated the genetic variance explained to be 4.4%

(Supplementary Data 12).

Considering the epidemiology and positive genetic correlation that has been reported between ET and Parkinson’s disease (PD) and depression12, we estimated the genetic correlation between ET

and these two phenotypes using the most recent GWASs and cross-trait LD score regression. In line with previous reports, we observed a positive genetic correlation between ET and these

phenotypes (PD15, rg = 0.28, P = 1.1 × 10−6; depression16, rg = 0.15, P = 3.4 × 10−5, Supplementary Data 13). In addition, we estimated the genetic correlation between ET and summary data

from 1142 published GWASs (P-threshold ≤ 0.05/1142 = 4.4 × 10−5) and found that ET correlates most strongly with anxiety-related phenotypes (e.g., feeling nervous, rg = 0.20, P = 2.0 × 10−6,

Supplementary Data 13).

We report a GWAS meta-analysis of ET that combines 16,480 cases and expands results from previous GWASs by identifying 12 variants at 11 loci, of which 8 are novel. We leveraged mRNA

expression, including splicing, plasma protein measurements and predicted coding effects to highlight seven putative causal genes and the biological roles of some of the variants. Through

gene-set enrichment analysis, we underscored the involvement of dopaminergic and GABAergic neurons in ET, as well as the biological significance of the Rho GTPase cycle. We did not find

high-impact variants segregating in families with high prevalence of ET. We showed a positive genetic correlation between ET and PD, depression, and anxiety-related phenotypes.

Based on functional annotation, we highlighted seven genes that may participate in the pathogenesis of ET. One of the candidate causal genes is CA3 which encodes carbonic anhydrase III and

is in close proximity ( >1 Mb) to other carbonic anhydrase genes including CA1, CA2, and CA13. Carbonic anhydrase inhibitors represent a class of drugs that have demonstrated the ability to

improve tremors, potentially through modulating brain pH levels. Additionally, acidification facilitates GABA receptor potentiation which may facilitate the effect of the inhibitors, on

tremor and seizures17,18. Primidone, an anti-epileptic drug widely used to treat ET patients, has been shown to inhibit carbonic anhydrase II18. The lead variant at the CA3 locus confers

protection against ET and is highly correlated with a variant that associates (top cis-eQTLs) with decreased expression of CA3 in skeletal muscles. The variant also associates with decreased

plasma levels of carbonic anhydrase III and XIII. The high LD at the locus suggest a potentially shared biological mechanism or pathway through which the variants exert their effects.

Further research is needed to identify the most likely causal variants. Carbonic anhydrases are relevant proteins that may have an important role in the biology of ET. This notable finding

lends support to the hypothesis that inhibiting carbonic anhydrases could lead to improved tremor control. Thus, targeting the interplay of CA3 and its closely related enzymes might lead to

the development of more targeted and effective treatments for individuals suffering from ET.

While ET may not be directly caused by imbalances in neurotransmitters, certain neurotransmitters have been implicated in its development and severity, such as GABA10,19,20. CPLX1 encodes

Complexin-1, a soluble presynaptic protein that specifically enhances transmitter release by increasing fusogenicity of synaptic vesicles21. CPLX1 is overexpressed in substantia nigra from

PD patients22 and dysregulation of the gene have been associated with neurogenetic disorders23, including myoclonic epilepsy24. In addition, homozygous Cplx1 knockout mice have the earliest

known onset of ataxia seen in a mouse model21,25,26. We identified an intronic variant in CPLX1 that increases the risk of ET and is the top cis-eQTL for CPLX1 in blood. This finding aligns

with previous research and strongly suggests the involvement of CPLX1 in the pathogenicity of ET.

OTX1 is a homeodomain transcription factor and is encoded by Orthodenticle homeobox 1. In the mammalian brain, OTX1 is expressed in the forebrain and midbrain during early stages of neural

development27 and at later stages and adulthood at high levels in layers 5 and 6, the deepest layers of the cortical plate28,29. Layer 5 neurons convey signals controlling motor behavior via

their projections to the colliculi, pons, and spinal cord30,31,32,33. Otx1 mutant mice have been reported to show spontaneous epileptic behavior and multiple abnormalities affecting certain

brain regions34. Otx1 mutant animal studies suggest that Otx1 is required for the development of normal axonal connectivity and the generation of coordinated motor behavior29. The ET

associated variant in EHBP1 is in high LD with a missense variant in the same gene and is, additionally, highly correlated with two intronic variants in EHBP1 and one variant in OTX1, all of

which are top cis-eQTLs for OTX1 expression in blood and neutrophiles. Based on these findings, our observations suggest that the intronic variant in EHBP1 may contribute to the risk of ET

by potentially upregulating the expression of OTX1. Consequently, OTX1 emerges as a promising candidate gene that could play a significant role in the underlying pathogenic mechanism of ET.

However, it is important to note that we did not investigate protein levels of OTX1, as it is neither measured on the Somalogic nor Olink platforms.

GCKR has been associated with high serum uric acid and purine metabolism disorders35. Extrapyramidal signs such as tremor are often observed in these disorders36. Individuals with high serum

uric acid might experience tremors attributed to these metabolic issues, yet, due to the lack of routine serum uric acid testing, they could be incorrectly diagnosed with ET. Whether the

tremor associated with the GCKR variant is a phenocopy or typical ET needs to be investigated further.

GABAergic dysfunction, consistently observed in ET patients10,19,37, is a focal point of research, but its genetic underpinnings remain unidentified. Our gene-set enrichment analysis

reinforces the proposed role of GABA in ET, yet the exact role of GABA in the causative framework requires further elucidation. In addition, our analysis found enrichment for dopaminergic

neurons, a crucial regulator of extrapyramidal movement. Given the shared phenotypic and genetic traits between ET and PD, the association with dopaminergic neurons is anticipated,

particularly as their selective degeneration in the substantia nigra pars compacta characterizes PD38. Notably, neurologist have long suspected a potential link between ET and PD, but

definitive evidence for this relationship has remained elusive39. Furthermore, our analysis underscores the significance of various biological processes, most notably the Rho GTPase cycle.

Rho GTPases regulate the actin cytoskeleton of dopaminergic neurons, thus influencing their degeneration40,41, and have been implicated in PD41,42. Interestingly, our findings underscore the

significance of stress response regulation, especially given the genetic overlap between ET and anxiety phenotypes. ET patients exhibit intensified tremors under stress, and anti-anxiety

medications, such as Clonazepam, prove highly effective in alleviating these tremors.

Familial clustering of ET is well recognized. However, estimates of the proportion with a family history is highly debated and ranges from as low as 17% to as high as 100%43. Linkage studies

have identified susceptibility loci on 3q1344 and 2p24.145 but others have shown absence of linkage at these loci46. The absence of a significant difference between the effects of sporadic

and familial cases and the lack of high-impact variants segregating in several large Icelandic families, underscores the potential that ET may be predominantly influenced by common variants

or a combination of such variants, rather than rare variants. To gain deeper insights into the contribution of common variants on ET risk, the creation of a polygenic risk score would be

valuable. A PRS analysis, if conducted with larger and more diverse datasets, could offer further clarity on the polygenic nature of ET and thus, the assembly of larger cohorts in future

research holds promise to increasing our understanding of the complex genetics of ET. Another limitation lies in the lack of ethnic diversity within the datasets studied. As an increasing

amount of genotypic and phenotypic data becomes available for diverse ethnic backgrounds, the inclusion of greater diversity in future studies could be helpful in uncovering

ethnicity-specific genetic contributions and advancing our understanding of the genetic underpinnings of ET.

In the previous GWAS conducted on ET, a subset consisting of 216 cases from the UK Biobank ET data was used. Regrettably, we could not ascertain whether these particular cases overlap with

the UK Biobank cases utilized in our current study. It is worth mentioning that even if all of these cases overlap with our data, they represent only 2% of the total 9303 cases (excluding

cases from the previous GWAS). Given their small proportion, the exclusion of these cases would not significantly impact the results or conclusions of our study.

To conclude, through a comprehensive GWAS meta-analysis and a multiomics approach using a substantial cohort, we have advanced our understanding of the genetics and pathogenesis of ET. This

progress not only enhances our knowledge of this complex and prevalent neurological disorder but can also form the basis for future investigations into treatment strategies and personalized

interventions.

In this study, ET cases were defined using International Classification of Diseases 10 (ICD-10) code G25.0 or ICD-9 code 333.1 in all datasets, as described in detail below, in addition to

the sample defined by Liao et al.12. All ethical regulations relevant to human research participants were followed. The data used in the GWAS meta-analysis were collected through studies

approved by ethics committees governing each dataset and written informed consent was obtained from all participants. Personal identifiers of participants’ data were encrypted for privacy

protection purposes in accordance with the regulation in each country. Genetic ancestry quality control was performed for all datasets47,48,49,50 and participants were genotypically verified

as being of European descent. In total, we studied data from 16,480 ET cases and 1,936,173 controls (Fig. 1 and Supplementary Data 1).

A large fraction of the Icelandic population has participated in a research program at deCODE genetics. Participants donated blood or buccal samples after signing a broad informed consent

allowing the use of their samples and data in various projects approved by the National Bioethics Committee (NBC). The data in this study was approved by the NBC (VSN-17-142-V5;

VSNb2017060004/03.01) following review by the Icelandic Data Protection Authority. All personal identifiers of the participants’ data were encrypted in accordance with the regulations of the

Icelandic Data Protection Authority. The Icelandic ET cases were identified from medical records, filed from 1985 to 2022, through collaboration with physicians at Landspitali—National

University Hospital in Reykjavik, the Registry of Primary Health Care Contacts, and the Registry of Contacts with Medical Specialists in Private Practice.

The Copenhagen Hospital Biobank (CHB) is a research biobank, which contains samples obtained during diagnostic procedures on hospitalized and outpatients in the Danish Capital Region

hospitals. Data analysis was performed under the Developing the basis for personalized medicine in degenerative and episodic brain disorders protocol, approved by the National Committee on

Health Research Ethics (H-21058057). The Danish Blood Donor Study (DBDS) Genomic Cohort is a nationwide study of ~160,000 blood donors51. The Danish Data Protection Agency (P-2019-99) and

the National Committee on Health Research Ethics (NVK-1700407) approved the studies under which data on DBDS participants were obtained. The DBDS data requested for this study was approved

by the DBDS steering committee.

The Estonian Biobank is a population-based cohort of approximately 210,000 participants, each accompanied by a variety of phenotypic and health-related data52. Upon recruitment, participants

granted permission through signed consents for subsequent linkage to their electronic health records, enabling the longitudinal accumulation of phenotypic details. The Estonian Biobank

facilitates access to the records from the National Health Insurance Fund Treatment Bills (since 2004), Tartu University Hospital (since 2008), and North Estonia Medical Center (since 2005).

For each participant, data is available on diagnoses coded in ICD-10 and drug dispensing records, including ATC codes, prescription statuses, and purchase dates (when available). The

activities of the EstBB are regulated by the Human Genes Research Act, which was adopted in 2000 specifically for the operations of the EstBB. Analysis of individual level data from the

EstBB was carried out under ethical approval 1.1-12/624 from the Estonian Committee on Bioethics and Human Research (Estonian Ministry of Social Affairs), using data according to release

application [6-7/GI/29 977] from the Estonian Biobank.

The Hordaland Health Study (HUSK) is a community-based study in Western Norway conducted as a collaboration between the University of Bergen, the Norwegian Health Screening Service and the

Municipal Health Service in Hordaland (https://husk-en.w.uib.no/)53. In 1992–93 and 1997–99 participants were invited based on year of birth and site of residence. Residents from Hordaland

County born 1950–52 and residents from Bergen and three neighboring municipalities born 1925–27, in addition to a random sample born 1926–49 were invited in 1992–93. In 1997–99, previous

participants born 1950–51 and 1925–27 were reinvited, in addition to all residents in Hordaland County born 1953–57. In total, approximately 36,000 individuals participated in the study,

18,000 in 1992–93 and 26,000 in 1997–99, with some participating at both times. ET cases were identified through diagnostic codes reported in the patient registry during 2008 to 2021. The

HUSKment study is approved by the Regional Committee for Medical Research Ethics Western Norway, reference 2018/915.

The UK Biobank resource has collected extensive phenotype and genotype data from ~500,000 participants in the age range 40–69, from across the UK after signing an informed consent for the

use of their data in genetic studies54. The North West Research Ethics Committee reviewed and approved UK Biobank’s scientific protocol and operational procedures (REC Reference Number:

06/MRE08/65). This study was conducted using the UK Biobank resource under application number 42256. ET cases were identified in General Practice clinical event records (Field ID 42040) and

UK hospital diagnoses (Field ID 41270 and 41271).

Participants, voluntary US residents over the age of 18 years, were recruited by The Intermountain Inspire Registry and The HerediGene: Population study55, a large-scale collaboration

between Intermountain Healthcare, deCODE genetics, and Amgen, Inc (https://intermountainhealthcare.org). The Intermountain Healthcare Institutional Review Board approved this study, and all

participants provided written informed consent prior to enrollment.

The Clinical Research in Neurology (CRIN) provides an umbrella structure for subject enrollment in observational and genetic studies in neurology, consent-approved data sharing across

studies and disorders, and consistent sample processing. Participants were recruited under the CRIN protocol through support from Emory Clinical Research Center NIH/NCRR M01 RR00039 (CRIN

Infrastructure support). The study was approved by the Emory Institutional Review Board (IRB) and informed consent was obtained from all subjects. ET genotyping work was done under specific

IRB protocols. Samples were drawn from either review of previously enrolled subjects in the CRIN database, or prospective enrollment of ET subjects into CRIN/ET observational and genetics

work. All subjects underwent a basic structured interview for demographics and family history. A Folstein Mini Mental Status Exam was administered to all CRIN subjects by trained CRIN

personnel supervised by a neuropsychologist per published guidelines. All CRIN database subjects enrolled prior to January 2007 with a reported diagnosis of 333.1 were reviewed. ET subjects

were called in for full in-person assessments whenever possible. ET subjects mid-2006 onward were recruited through IRB-approved ads in the Emory Movement Disorders and Neurosurgery deep

brain stimulation group clinics, and ET community education events. ET subjects and family members were examined directly by at least one movement disorders specialist; two independent exams

were obtained whenever possible (a tremor rating scale derived from the Fahn-Tolosa-Marin scale and Tremor Research Group scale items, the motor United Parkinson Disease Rating Scale,

Tinetti gait and balance scales56, tandem gait57, and assessment for dystonia). Semi-structured interviews included ET specific questions derived from the Fahn-Tolosa-Marin scale and WHIGET

studies58. CRIN review and new enrollment subjects were given a research diagnosis of ET using Movement Disorders Society and Tremor Research Group criteria. ET cases with either Parkinson’s

disease or dystonia were excluded. Subjects were excluded based on a number of criteria; if an in-person exam and re-interview determined a different diagnosis, if movement disorders

clinical notes listed an uncertain or different final diagnosis (i.e., medication induced tremor), if there was an incomplete examination, lack of medication response, or other data to

clearly establish an ET research diagnosis.

The genomes of 63,460 Icelanders were whole genome sequenced (WGS)47,59 using GAIIx, HiSeq, HiSeqX, and NovaSeq Illumina technology to a mean depth of 38×. Genotypes of single nucleotide

polymorphisms (SNPs) and insertions/deletions (indels) were identified and called jointly with Graphtyper60,61. Over 173,000 Icelanders (including all WGS Icelanders) were genotyped using

various Illumina SNP arrays47,59. The genotypes were long-range phased62, which allows for improving genotype calls using haplotype sharing information. Subsequently, extensive encrypted

genealogic information was used to impute variants into the chip-typed Icelanders, as well as ungenotyped close relatives63 to increase the sample size and power for association analysis.

The Danish samples from the CHB and DBDS were genotyped using Illumina Global Screening Array, and long-range phased together with 270,627 genotyped samples from North-western Europe using

Eagle264. Samples and variants with less than 98% yield were excluded. A haplotype reference panel was prepared in the same manner as for the Icelandic data47,62 by phasing genotypes of

25,215 WGS individuals (sequenced with NovaSeq Illumina technology to a mean depth of 20×) from North-western Europe, including 8,360 Danes, using the phased chip data. Graphtyper60,61 was

used to call the genotypes which were subsequently imputed into the phased chip data. WGS, chip-typing, quality control, long-range phasing, and imputation from which the data for this

analysis were generated was performed at deCODE genetics.

The samples from the Estonian Biobank were genotyped at the Genotyping Core Facility of the Institute of Genomics at the University of Tartu, using the Illumina Global Screening Array. In

total, 212,955 samples passed quality control. Samples were excluded from the analysis if their call-rate was below 95% or if the gender, identified by the heterozygosity of the X

chromosome, did not align with the gender documented in phenotype data. Variants were excluded if the call-rate was below 95% or if the HWE p-value was less than 1e-4 (only autosomal

variants). In addition, SNPs that showed potential traces of batch bias were removed. Two batch bias control steps were performed: 1) SNPs that showed poor cluster separation results among

any of Estonian Biobank genotyping experiments were removed. The threshold for SNP removal was Illumina GenTrain score