The risks of pots after covid-19 vaccination and sars-cov-2 infection: more studies are needed

- Select a language for the TTS:

- UK English Female

- UK English Male

- US English Female

- US English Male

- Australian Female

- Australian Male

- Language selected: (auto detect) - EN

Play all audios:

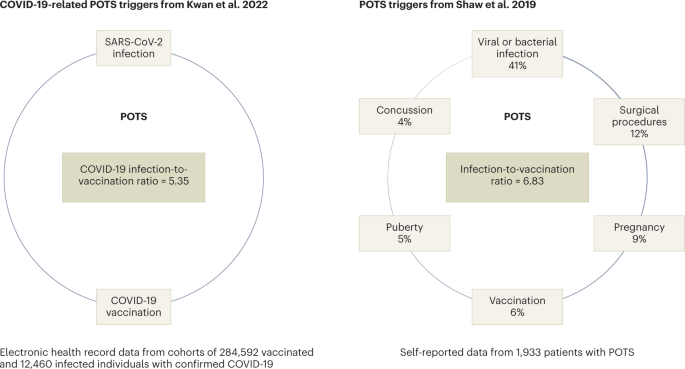

Postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome (POTS) can follow COVID-19 as part of the post-acute sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 infection, but it can also develop after COVID-19 vaccination, although

at a lower frequency. Vaccines represent one of the most groundbreaking scientific advances that substantially reduced the mortality and morbidity associated with various infectious

pathogens. Since the introduction of COVID-19 vaccines in the USA in December 2020, vaccination against SARS-CoV-2 has remained the most effective and influential global public health

strategy to mitigate the pandemic. However, reports of post-vaccination adverse events involving various cardiovascular and neurological manifestations, including POTS, have been mounting in

the Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System1. POTS, a common disorder of the autonomic nervous system, is characterized by an increase in heart rate of at least 30 beats per minute within 10

minutes of standing and symptoms of orthostatic intolerance, such as pre-syncope, palpitations, light-headedness, generalized weakness, headache and nausea, with symptom duration exceeding

three months2. In the USA, the pre-pandemic prevalence of POTS has been estimated to be in the range of 500,000–3,000,000 people, affecting predominantly women of reproductive age and

roughly 1 in 100 teenagers3. However, current prevalence is likely significantly higher owing to post-COVID-19 POTS, which can develop as part of the post-acute sequelae of SARS-CoV-2

infection (PASC)4,5. New-onset POTS can also follow vaccination (Fig. 1) and was reported in the literature after immunization with Gardasil, a human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine, in 2010

and, more recently, after the administration of COVID-19 vaccines6,7,8. However, a causative relationship between HPV vaccines and increased incidence of POTS has not been thoroughly

investigated. This is despite several case series reported from different countries and two studies that demonstrated an increased signal for POTS and its associated symptom clusters

following HPV vaccination, based on data from the World Health Organization’s pharmacovigilance database and a meta-analysis of clinical study reports from 24 clinical trials9,10,11. In a

study published in this issue of _Nature Cardiovascular Research_, Kwan et al. examined the frequency of new POTS-associated diagnoses — POTS, dysautonomia, fatigue, mast cell disorders and

Ehlers–Danlos syndrome — before and after COVID-19-vaccination12. They found that the odds of POTS and associated diagnoses were higher in the 90 days after vaccine exposure than the 90 days

before exposure, with a relative risk increase of 33%12. Furthermore, the authors showed that the odds of new POTS-associated diagnoses following natural SARS-CoV-2 infection were higher

than pre-infection with an increased risk rate of 52%. The study is based on a large series of approximately 300,000 vaccinated individuals from one geographic territory in the USA (Los

Angeles County), with 0.27% new post-vaccination POTS diagnoses compared with 0.18% in the pre-vaccination period, giving an odds ratio of 1.52 for post-vaccination POTS diagnoses12.

Accumulating all POTS-associated diagnoses in one group gave slightly lower odds. Interestingly, among 12,460 individuals with confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection, the pre-infection incidence of

POTS was 1.73%, compared with 3.42% after infection. This suggests that those with symptomatic COVID-19 infection were more likely to develop POTS in general, and that the risk of

post-infection POTS is higher than post-vaccination POTS in this cohort12. The study has some limitations. First, the accuracy of POTS and POTS-associated diagnoses is crucial for study

validity. Second, the general awareness and diagnostic vigilance of POTS and access to adequate diagnostic modalities are decisive for POTS incidence reliability. Third, the generalizability

of this report is limited to a specific population. Moreover, the traditional POTS diagnostic criteria require symptoms to occur over a duration of at least 3 months — that is, at least 90

days — which is the assessed period. As such, some of the affected individuals may have recovered later. We therefore cannot exclude the possibility that the incidence of POTS and

POTS-associated diagnoses was overestimated. Despite these limitations, the study by Kwan et al.12 is of major importance to POTS research and patient care for several reasons. First, it

undeniably establishes POTS and dysautonomia in general as adverse events after vaccination that should be recognized and investigated as other well-accepted post-vaccination syndromes, such

as Guillain–Barre syndrome and acute disseminated encephalomyelitis. Second, it clearly demonstrates that POTS and POTS-associated comorbidities occur more frequently after COVID

vaccination than before, and much more frequently than myocarditis, which, despite increasing at a higher rate after vaccination, remains a rare post-vaccination complication. Consequently,

POTS and POTS-associated conditions may be among the most common adverse events after COVID-19 vaccination. Third, it reaffirms that POTS occurs at a high rate after SARS-CoV-2 infection and

is likely one of the major phenotypes of PASC. Fourth, the rate of new POTS diagnoses made after natural SARS-CoV-2 infection was higher than after COVID-19 vaccination, although a direct

comparison is not possible at this stage, given the intrinsic differences in POTS incidence at baseline in the two cohorts. The last point is particularly poignant and clinically relevant,

as it provides compelling evidence that can be referenced during physician–patient encounters in support of vaccination and against vaccine hesitancy. We hope that large prospective studies

utilizing the new ICD-10 diagnostic code specific for POTS, which has been implemented by the US Center for Disease Control and Prevention committee as of October 1, 2022, can be conducted

in the future. Similarly, mechanistic studies investigating POTS following SARS-CoV-2 infection and COVID-19 vaccination are needed to determine causation and delineate the underlying

immune-mediated mechanism, possibly involving the spike protein and/or formation of autoantibodies to G-protein-coupled receptors and other targets in the cardiovascular system and beyond13.

Furthermore, developing a screening pathway with genetic testing to identify at-risk individuals with a genetic predisposition toward post-vaccination adverse events is necessary, and would

lead to a reduction in serious post-vaccination adverse events and promote public trust and vaccination compliance. As we continue to navigate and mitigate the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic and

long-term post-COVID-19 complications with the help of COVID-19 vaccines, the need to invest in POTS research to advance our understanding, diagnosis and management of POTS — a common

sequela of both SARS-CoV-2 infection and COVID-19 vaccination — has never been more pressing. CHANGE HISTORY * _ 11 SEPTEMBER 2023 Since publication of this News & Views, the source

article it discusses (Kwan et al., https://doi.org/10.1038/s44161-022-00177-8 (2022)) has been updated to clarify that a fully-adjusted comparison of odds of POTS attributable to vaccination

versus infection is not possible within the study design, given the two mutually exclusive populations, leading to changes in this article’s title, and descriptions of POTS risk in the

abstract, fourth and seventh paragraphs. The changes are made in the HTML and PDF versions of the article. _ REFERENCES * Chen, G. et al. _Front Immunol._ 12, 669010 (2021). Article CAS

PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Fedorowski, A. _J. Intern. Med._ 285, 352–366 (2019). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Mar, P. L. & Raj, S. R. _Annu Rev Med._ 71,

235–248 (2020). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Blitshteyn, S. & Whitelaw, S. _Immunol. Res._ 69, 205–211 (2021). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar *

Bisaccia, G. et al. _J. Cardiovasc. Dev. Dis._ 8, 156 (2021). CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Shaw, B. H. et al. _J. Intern. Med._ 286, 438–448 (2019). Article CAS PubMed

PubMed Central Google Scholar * Blitshteyn, S. _Eur. J. Neurol._ 17, e52 (2010). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Eldokla, A. M. & Numan, M. T. _Clin Auton. Res._ 32, 307–311

(2022). Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Blitshteyn, S. et al. _Immunol Res._ 66, 744–754 (2018). Article PubMed Google Scholar * Chanlder, R. E. et al. _Drug Saf._ 40,

81–90 (2017). Article Google Scholar * Jorgensen, L. et al. _System. Rev._ 9, 43 (2020). Article Google Scholar * Kwan, A. et al. _Nat. Cardiovasc. Res._

https://doi.org/10.1038/s44161-022-00177-8 (2022). Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Fedorowski, A. et al. _Europace_ 19, 1211–1219 (2017). Article PubMed Google Scholar

Download references AUTHOR INFORMATION AUTHORS AND AFFILIATIONS * Department of Neurology, Jacobs School of Medicine and Biomedical Sciences, University at Buffalo, Buffalo, NY, USA Svetlana

Blitshteyn * Dysautonomia Clinic, Williamsville, NY, USA Svetlana Blitshteyn * Department of Cardiology, Karolinska University Hospital, and Department of Medicine, Karolinska Institute,

Stockholm, Sweden Artur Fedorowski Authors * Svetlana Blitshteyn View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Artur Fedorowski View author

publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar CORRESPONDING AUTHOR Correspondence to Svetlana Blitshteyn. ETHICS DECLARATIONS COMPETING INTERESTS The authors

declare no competing interests. RIGHTS AND PERMISSIONS Reprints and permissions ABOUT THIS ARTICLE CITE THIS ARTICLE Blitshteyn, S., Fedorowski, A. The risks of POTS after COVID-19

vaccination and SARS-CoV-2 infection: more studies are needed. _Nat Cardiovasc Res_ 1, 1119–1120 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s44161-022-00180-z Download citation * Published: 12 December

2022 * Issue Date: December 2022 * DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s44161-022-00180-z SHARE THIS ARTICLE Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content: Get

shareable link Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article. Copy to clipboard Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative