The greatest artist of the 20th century: a reply to jay elwes | thearticle

- Select a language for the TTS:

- UK English Female

- UK English Male

- US English Female

- US English Male

- Australian Female

- Australian Male

- Language selected: (auto detect) - EN

Play all audios:

Today we publish an exhaustively investigated, closely argued yet highly entertaining essay by Jay Elwes on the question: who was the greatest artist of the 20th century? To ask that

question is to answer it in a highly personal way, with all the inevitable idiosyncrasies, arbitrary judgements, individual tastes and limitations of knowledge and culture that come with it.

You have to plump for something and someone: one art form over others, one artist above the rest. And so he does, with admirable logic, following a process of elimination that is almost

entirely convincing, to conclude that the supreme art of the last century was music and that the supreme musician was none other than Ella Fitzgerald. Almost convincing — but not quite. Lady

Ella’s regal status in the world of jazz has never been in doubt, nor her mastery of a uniquely wide repertoire that ranged far beyond that world. Her perfect pitch was merely one indicator

of a singing talent that was unsurpassed in her day and, thanks to her recordings, remains vividly present in ours. Her lifespan of 79 years (1917-1996) wasn’t especially long by the

standards of the present, but long enough to encompass both halves of the century. Being a black American and a woman meant that she had to contend with adversity at every stage, which is a

bonus when compared with more fortunate contemporaries. Ella Fitzgerald qualifies for the accolade awarded by Elwes on every count. Except one. Like all singers — or indeed other

musicians, actors, dancers and other exponents of the performing arts — Ella Fitzgerald was an interpreter of the works of others. As Elwes himself observes, “she was an African American who

rose to global renown by singing the compositions of Jewish American immigrants.” She was fortunate that her life coincided with a remarkable generation of composers — many though by no

means all of them Jewish — whose songs possessed a universal and enduring appeal. Without their inspiration, not to mention her collaboration with other great musicians such as Louis

Armstrong, her career would have been unthinkable. That inspiration was, of course, mutual: like many other great singers, she was a spur to songwriters, who gave of their best with her

voice in mind. We may well feel, as many did and do, that her interpretations were definitive. But the point about the composer’s art, as opposed to that of the performer, is that it is

open-ended: new generations will make of these songs what they will, for as long as people care to listen. A singer’s legacy is complete when they die, or indeed when they cease to perform.

Indeed, we are fortunate to have such a rich archive of recordings and film for the performing artists of the last century. Their predecessors in earlier eras were doubtless no less

bewitching, but we have only second-hand knowledge of what audiences of yore heard and saw. That musical performance valued no less highly in previous centuries is demonstrated not only by

the fame and fortune of the performers, but by the fact that two of the very greatest composers of all time, Bach and Mozart, both married their favourite singers: Anna Magdalena and

Constanza respectively. Wagner had a love affair with another singer, Mathilde Wesendonck, while his second wife was the daughter of Liszt, who has a strong claim (on the basis of the

virtuosity his compositions) to have been the greatest pianist of the 19th century. All the great composers were also leading performers, too — they had to be in order to earn a living; even

that wasn’t always enough. My contention, then, is that it is merely the good fortune of technology that has preserved the achievements of 20th-century performance artists and thereby

inflated their claims. But for that accident of history, we would hardly be able to consider them alongside the less visible or audible geniuses who created the works that they sang, played

or danced. The same applies to theatre or film: it is the playwrights and directors who loom ever larger in retrospect, while the actors seem more ephemeral. Perhaps if the technology had

existed we would rate Garrick as highly as his friends Johnson, Reynolds and Burke, celebrate Sir Henry Irving no less than Wilde or Shaw, or admire Richard Burbage and other actors of

Shakespeare ’ s time as much as the Bard. It would certainly be fascinating to compare their interpretations with those of modern stars of stage and screen, from Olivier and Gielgud to the

late Sir Anthony Sher. Who knows what Aeschylus and Sophocles would have made of our performances of their tragedies, or whether Racine would have cared for Diana Rigg’s Phèdre? (Perhaps not

even sub- or surtitles would have sufficed to make them comprehensible.) My point is not to denigrate the great musicians and actors with whom we have been blessed, merely to preserve a

little humility about changing tastes and traditions of performance. For my money, the immortals will always be those who write, compose, paint, sculpt, build or otherwise create the

original works of art which others may interpret or execute. Performers may well be the most highly rewarded, fêted and beloved in their lifetimes and even posthumously — Ella Fitzgerald is

a perfect example — but the passage of time eventually buries all reputations except those whose works transcend their epoch. The visual arts are especially fragile, of course: many of the

greatest works of antiquity survive only in copies or not at all, while excessive so-called restoration continues to ruin many great paintings. Words and notes are ageless, however: we can

recreate the imaginative and musical worlds of the past as we please and each generation will do so by its own lights. The greatest artist of the 20th century? The choice is impossible,

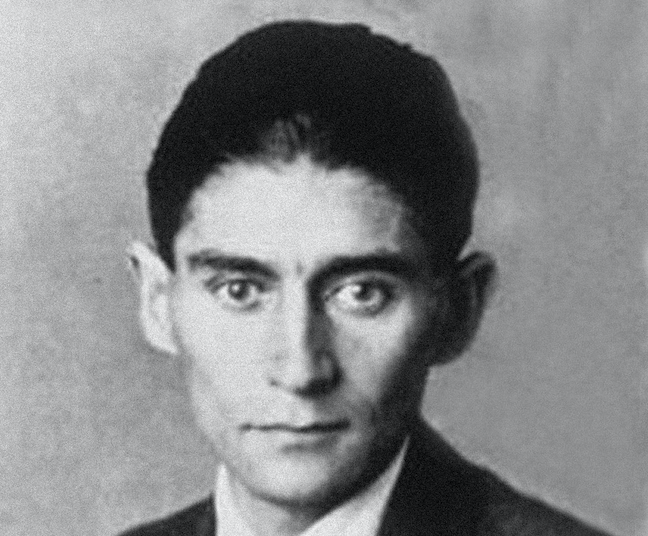

but I admire those who dare to plump for a single name. A word of warning, though: the 21st century is already usurping the legacy of the 20th. When one googles Kafka (pictured above), what

comes up first is still the great writer’s Wikipedia page — but thereafter a piece of software that has borrowed his name. For how much longer? Sibelius the composer has been supplanted on

Google by a music notation software. In the virtual universe writers and composers are reduced to the status of “content providers”. Artificial intelligence is already presuming to

“complete” symphonies; soon, no doubt, our silicon _Doppelgänger_ will try their hands at writing novels, plays and poems. Who can say for sure whether from the perspective of posterity the

greatest artist of the 21st century will even be a human being?