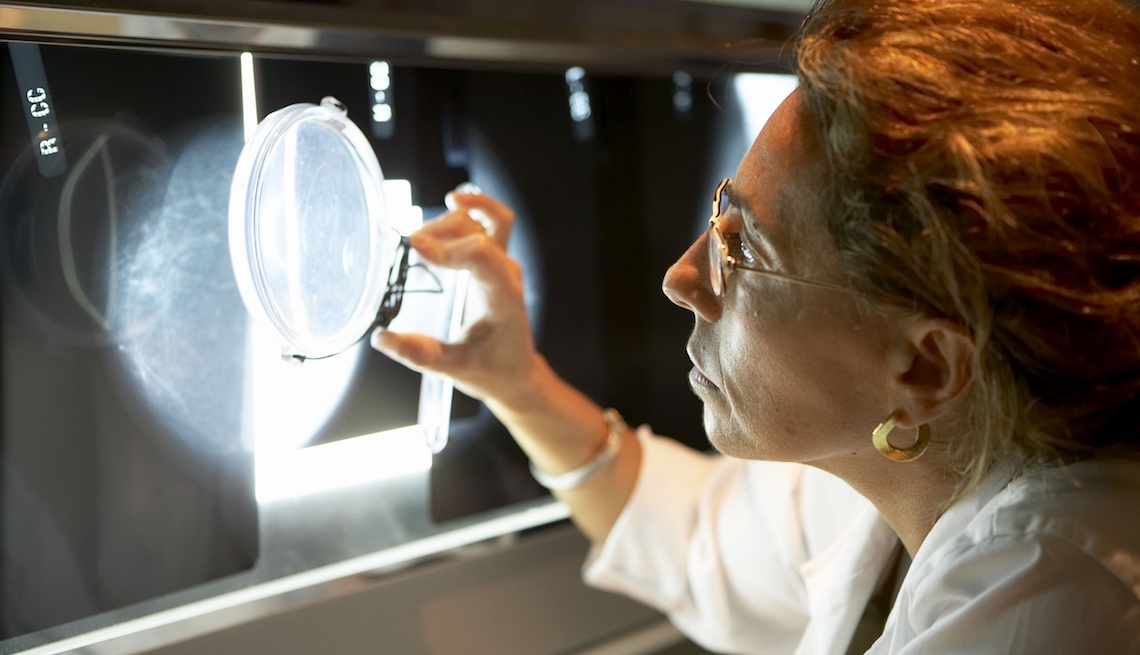

Fda proposes more-detailed mammography results

- Select a language for the TTS:

- UK English Female

- UK English Male

- US English Female

- US English Male

- Australian Female

- Australian Male

- Language selected: (auto detect) - EN

Play all audios:

What's still unclear: what a woman should do with the information. The recommendations don’t offer any suggestions for next steps, beyond discussing options with their doctor. “There’s

no consensus nationally about among breast experts or the general provider population what the correct response to this should be,” says Rhodes. A woman could choose to have supplemental

tests; among the options are 3-D mammography (more formally, digital breast tomosynthesis, or DBT), which has replaced standard 2-D mammography at many screening centers and has been shown

to be slightly better at detecting cancer; ultrasound; and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). But while those last two tests are even better at detecting cancer, each has a few downsides,

says Friedewald, including that ultrasound produces a lot of alarming false positives. MRI is the best of these tests, but it is also much more expensive, Rhodes says, and tends to be used

only in high-risk women as a supplemental screening. Additional tests, such as molecular breast imaging, are being studied. “It’s a challenge because the legislation has preceded the data,”

Friedewald notes, “so we don’t quite know exactly where we want to head in terms of how to image these patients, and there really aren’t any guidelines.” The move to notify women about

breast density was spearheaded more than 15 years ago by a Connecticut woman named Nancy Cappello, who was diagnosed with advanced breast cancer in 2004, six weeks after being told her

mammogram was negative. Her doctor had never told her she had dense breast tissue, which would lower the chances that cancer would be discovered. She lobbied the Connecticut government,

which eventually passed a law requiring that women be notified if they have dense breasts. It also requires insurance to cover ultrasound screening if a woman wants a supplemental test.

Rhodes says some opponents were concerned that breast-density information would make women anxious, “but I think women have to fight back against what, to me, is a rather paternalistic

notion.” Many women want the information, even if it is sobering — and even though next steps are confusing. Last year the advocacy organization founded by Cappello, Are You Dense,

commissioned a survey of 1,500 women ages 40 to 74 who’d obtained a mammogram within two years, and almost 90 percent said they “completely or mostly agree” that they would rather know their

breast density type than not.