Vitreous surgery with direct central retinal artery massage for central retinal artery occlusion

- Select a language for the TTS:

- UK English Female

- UK English Male

- US English Female

- US English Male

- Australian Female

- Australian Male

- Language selected: (auto detect) - EN

Play all audios:

ABSTRACT AIM To evaluate the effectiveness of vitreous surgery with direct central retinal artery massage for the treatment of central retinal artery occlusion (CRAO). METHODS Vitreous

surgery with direct central retinal artery massage was performed on 10 consecutive patients with acute CRAO. After standard 3 port pars plana vitrectomy, a specially designed probe was used

to massage the central retinal artery on the optic nerve head or within the optic nerve or both. The best-corrected visual acuity was measured and fundus photograph was taken before

operation, at 24, 48 h and weekly intervals for at least 1 month postoperatively. RESULTS Circulation was restored immediately during the operation in four cases, gradually since the first

day after operation in four cases. There was no change in the remaining two cases, among which, central retinal vein occlusion occurred in one case 5 days later. No other complications

occurred. At 2 months postoperatively, visual acuity had improved for three or more lines in six cases (60%), and remained the same in the rest of the cases. CONCLUSIONS Vitreous surgery

with direct central retinal artery massage seems to be an effective and relatively safe treatment for CRAO. SIMILAR CONTENT BEING VIEWED BY OTHERS CENTRAL RETINAL ARTERY CATHETERIZATION FOR

RETINAL ARTERY OCCLUSION WITH BALANCED SALT SOLUTION Article Open access 02 April 2025 ABERRANT FILLING OF THE RETINAL VEIN ON FLUORESCEIN ANGIOGRAPHY IN BRANCH AND HEMI-CENTRAL RETINAL

ARTERY OCCLUSION Article 28 December 2022 MACULAR VESSEL DENSITY IN CENTRAL RETINAL ARTERY OCCLUSION WITH RETINAL ARTERIAL CANNULATION Article Open access 08 November 2023 INTRODUCTION

Central retinal artery occlusion (CRAO) usually causes abrupt and irreversible visual loss. Although multiple therapeutic regimens have been proposed for it, the effect seems to be limited.

The visual prognosis for most patients was poor. Visual acuity increased by three or more lines in only 15% of the patients with or without treatment.1 Selective intra-arterial lysis has

been proposed for the treatment of CRAO in recent years. A meta-analysis of the published data showed that there may be marginal visual benefit, and it has potential serious adverse effects,

such as embolization of other parts of the vascular system, which might lead to stroke or even death.2 In this study, vitreous surgery with direct central retinal artery massage as a new

technique for the treatment of CRAO was investigated. To our knowledge, there have been no similar reports in the literature previously. PATIENTS AND METHODS PATIENTS This study was approved

by the Committee Review Board of Beijing Tongren Hospital. It consisted of 10 consecutive patients with acute CRAO who were treated with vitreous surgery with direct central retinal artery

massage between October 2005 and April 2007 in Beijing Tongren Hospital. Informed consent was obtained from all the patients before treatment. All the eyes included in our study showed

fundus features typical of acute CRAO, with abrupt painless visual loss. Criteria of exclusion: CRAO of more than 6 days' duration at initial examination; patients with a foveal sparing

cilioretinal artery; the caliber of the retinal vessels had returned to normal and angiographic images revealed a normal retinal circulation time; initial visual acuity better than counting

fingers. Before the surgery, best-corrected visual acuity, anterior and posterior segments of the eye were examined. Photography of the posterior pole of all the patients and fundus

fluorescein angiography (FFA) in some patients were performed. Laboratory tests were conducted for blood clotting, electrolytes, and blood sugar. Ten patients with an average CRAO period of

73 h (24 h to 6 days) were enrolled. The age of the patients ranged from 34 to 70 years, with an average of 48 years (Table 1). Nine patients had a history of arterial hypertension, in

which, one had a history of stroke 2 years ago, and three had a history of myocardial infarction. These patients were under drug therapy for high blood pressure. Other history of special

medical treatment was denied. Only one patient had no history of systemic diseases (Table 1). Temporal arteritis was excluded by examining the blood sedimentation rate. Retinal edema with

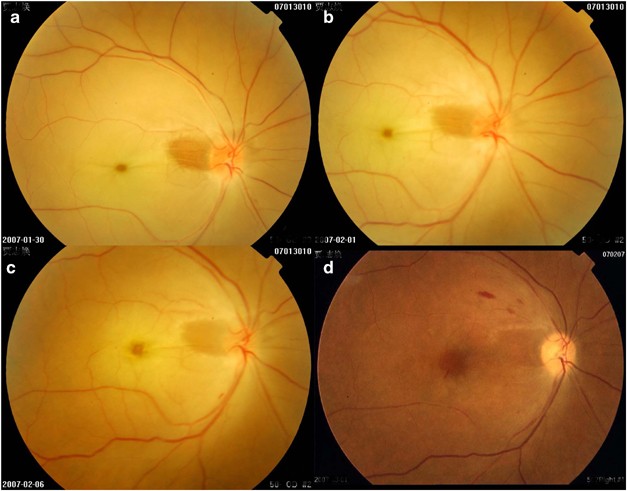

cherry red spot and narrowed retinal arteries were found in all the cases (Figure 1a). Initial visual acuity in these cases ranged from no light perception to counting fingers (Table 1).

Emboli of the central retinal artery were not detected in these cases. Small yellow-white emboli were found in the retinal arterioles but not on the optic disc in two cases. FFA was

performed in five patients. The arteriovenous transit times ranged from 18 to 311 s, with an average of 138 s. TECHNIQUE OF VITREOUS SURGERY WITH DIRECT CENTRAL RETINAL ARTERY MASSAGE After

a standard 3 port pars plana vitrectomy, a special probe made of nickel titanium and extended from a 19 gauge support shaft (Figure 2) was put on the central bifurcation of the retinal

artery, and slight pressure was applied until entire flow cessation of the artery occurred, followed by 2 s of release. This was repeated for 5–6 times. If small pieces of embolus were seen

moving downstream from the central retinal artery and the caliber of the retinal vessels increased, then the operation could be finished. If no change of the retinal circulation occurred

after this procedure, a microvitreoretinal blade was used to make a small incision along the central retinal artery in the optic nerve head, and then the special probe was introduced

carefully into the incision and advanced into the optic nerve head toward the lamina cribrosa along the central retinal artery. The site of the incision was carefully selected to avoid major

branches of the retinal arterioles and venules. As the probe moving toward the lamina cribrosa, slight pressure was applied against the central retinal artery until entire blood flow

cessation occurred, followed by 2 s of release. This procedure was repeated for 5–6 times. Approximately 3–4 mm of the probe entered the optic nerve head. If the caliber of the retinal

arteries increased, then the operation could be finished. If no change of the retinal circulation occurred following this procedure, then a sclera depressor was used to press the optic nerve

head until slight deformation of the optic nerve head was observed under the surgical microscope, followed by 2 s of release. Again, this procedure was repeated for 5–6 times before the

surgery was completed. This procedure was achieved by inserting a sclera depressor retrobulbarly through the superonasal conjunctival incision. The whole movement of the sclera depressor

along the superonasal surface of the sclera toward the optic nerve head was observed under the surgical microscope. PATIENT FOLLOW-UP Follow-up examinations were performed at 24 h, 48 h, 1

week, 2 weeks, 3 weeks, 4 weeks and 2 months after intervention. This included test of the best-corrected visual acuity, fundus photography, and FFA. RESULTS Ten patients with acute CRAO

were treated by vitreous surgery with direct central retinal artery massage. In four cases, small pieces of yellow-white embolus were seen dislodged from the central retinal artery and moved

downstream along one branch of the retinal arterioles toward the periphery of the fundus following the direct central retinal artery massage. At the same time, the vessel caliber of both

the retinal artery and vein increased, indicating that the retinal blood flow improved. The central retinal artery became narrowed again 2 days after operation in one patient, but reopened

on the third day postoperatively. In other six cases, no change of retinal circulation was found during the operation, among which, retinal circulation improved in four cases 24–48 h after

operation, remained the same in two cases. The arteriovenous transit times on FFA performed within the first 2 days postoperatively were normal or nearly normal as shown in Table 2 (normal

arteriovenous transit times were ⩽11 s).3 FFA was not performed for the two patients with no change in the ophthalmoscopic appearance. During follow-up visits, retinal artery occlusion did

not recur in the eight cases with improved retinal circulation (Figures 1, 3 and 4). Visual acuity improvement occurred within the first week after operation in most patients. In some

patients, visual acuity gradually improved during the first 2 months postoperatively (Table 1). During the operation, localized retinal hemorrhage on the optic nerve head occurred in most

cases due to injury of the capillaries at the operation site, which was controlled by increasing the infusion pressure. Postoperative FFA showed slight staining of fluorescence at the

operation site on the optic nerve head (Figure 4). In one case, central retinal vein occlusion occurred 5 days after operation. Iris neovascularization occurred 20 days later (Table 2).

Cryotherapy of the peripheral retina for 360 degrees was performed and the neovascularization of the iris regressed gradually after operation. No other serious complication occurred.

DISCUSSION Clinical and experimental studies have indicated that there was a time limit for CRAO to cause irreversible damage to the retina. If retinal circulation restored within this time

limit, retinal function could recover. In primates, the time limit was 105 min.4 In the clinic, this time limit could be much longer, because the occlusion in CRAO is seldom complete.5 It

was reported that vision recovered to different degrees within 12–33 h after CRAO.5,6 There was even a report that showed that vision could recover after 4 days of CRAO.7 In our study, for

all the patients with an occlusion time of 4 days or less, visual acuity improved in the cases that retinal blood circulation restored after surgery. For the patient with 6 days of

occlusion, visual acuity remained the same although retinal circulation restored postoperatively (Table 1). We cannot comment on the correlation between the occlusion time and the degree of

visual recovery, as the number of cases is too small. The common cause of CRAO is an embolus lodging in the central retinal artery. The actual position of the embolus is difficult to

determine. It may be immediately posterior to the lamina cribrosa5 or more posterior.8 In our study, pressing the central retinal artery in the optic nerve head with a probe or retrobulbarly

with a sclera depressor led to deformation and bending of the blood vessel wall. The vessel wall of the retinal artery is elastic, therefore, slight deformation and bending may not cause

any damage to the vessel wall. The emboli were made of cholesterol in 74%, calcified material in 10.5%, and platelet-fibrin in 15.5%.9 The emboli may be less flexible and more fragile in

comparison with the wall of the retinal arteries, so during the mechanical movement of the vessels induced by the probe, the embolus may be broken into smaller pieces and then be dislodged.

During the operation, emboli were seen dislodged and moving downstream with immediate restoration of retinal circulation after the direct central retinal artery massage in four of our cases,

indicating that mechanical movement may be effective to dislodge the embolus. In the other four cases, no embolus was seen during the operation, but the retinal circulation improved 24–48 h

postoperatively. This may be because the emboli were more adherent to the vessel wall or less fragile, which made it more difficult to be dislodged immediately. However, the direct retinal

artery massage may had loosened the embolus and made it readily dislodged or absorbed gradually, so 24–48 h after operation, retinal circulation restored. For two cases, circulation did not

recover, this may be due to that the position of the emboli was further posterior to the optic nerve head or there was no embolus at all. The diameter of the probe was 0.1 mm, similar to the

diameter of the central retinal artery (Figure 2). It was advanced into the optic nerve head in a parallel direction to the optic nerve fiber, and was pressed directly upon the blood vessel

wall, so it may cause little damage to the optic nerve. One day after operation, there was only slight staining at the operation sites on FFA, and most patients had an increased visual

acuity during follow-up study (Figure 4). This indicated that the operation caused no or negligible damage to both the central retinal artery and the optic nerve. Only one patient developed

central retinal vein occlusion 5 days after operation. This may be due to damage of the central retinal vein during the operation. As retinal circulation did not recover in this case during

follow-up study, slow blood flow in the vein might gradually caused thrombus formation at the site of injury, and finally resulted in central retinal vein occlusion. This indicated that the

operation had a potential risk of central retinal vein injury. Visual acuity improved by three or more lines in 6 out of 10 cases (60%). Forty percent of our patients had a final visual

acuity of 20/200 or better (Table 1). The visual outcome was better than that of conservative forms of treatment or natural course of the disease.1 Our study showed that vitreous surgery

with direct central retinal artery massage was relatively safe and may be effective in restoring blood circulation in patients with CRAO and improving the visual prognosis. Limitations of

our study included: noncomparative nature, limited number of patients, and delayed treatment due to patient referral. A randomized controlled trial is necessary to prove the effectiveness of

the treatment. REFERENCES * Mueller AJ, Neubauer AS, Schaller U, Kampik A . Evaluation of minimally invasive therapies and rationale for a prospective randomized trial to evaluate selective

intra-arterial lysis for clinically complete central retinal artery occlusion. _Arch Ophthalmol_ 2003; 121: 1377–1381. Article Google Scholar * Beatty S, Eong KGA . Local intra-arterial

fibrinalysis for acute occlusion of the central retinal artery: a meta-analysis of the published data. _Br J Ophthalmol_ 2000; 84: 914–916. Article CAS Google Scholar * Brown GC, Magargal

LE . Central retinal artery obstruction and visual acuity. _Ophthalmology_ 1982; 89: 14–19. Article CAS Google Scholar * Hayreh SS, Weingeist TA . Experimental occlusion of the central

artery of the retina. IV: Retinal tolerance time to acute ischemia. _Ophthalmology_ 1980; 64: 818–825. CAS Google Scholar * Rumelt S, Dorenboim Y, Rehany U . Aggressive systemic treatment

for central retinal artery occlusion. _Am J Ophthalmol_ 1999; 128: 733–738. Article CAS Google Scholar * Richard G, Lerche RC, Knospe V, Zermann H . Treatment of retinal arterial

occlusion with local fibrinolysis using recombinant tissue plasminogen activator. _Ophthalmology_ 1999; 106: 768–773. Article CAS Google Scholar * Duker JS, Drown GC . Recovery following

acute obstruction of the retinal and choroidal circulations: a case history. _Retina_ 1988; 8: 257–260. Article CAS Google Scholar * Hayreh SS, Zimmerman MB . Central retinal artery

occlusion: visual outcome. _Am J Ophthalmol_ 2005; 140: 376–391. Article Google Scholar * Arruga J, Sanders MD . Ophthalmologic findings in 70 patients with evidence of retinal embolism.

_Ophthalmology_ 1982; 89: 1336–1347. Article CAS Google Scholar Download references AUTHOR INFORMATION AUTHORS AND AFFILIATIONS * Ophthalmology Center of Beijing Tong-Ren Hospital,

Capital Medical University, Beijing, China N Lu, N-L Wang, G L Wang, X W Li & Y Wang Authors * N Lu View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar *

N-L Wang View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * G L Wang View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar

* X W Li View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Y Wang View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar

CORRESPONDING AUTHOR Correspondence to N-L Wang. ADDITIONAL INFORMATION _Competing interest statement:_ There are no proprietary or commercial interests related to the article _Previous

presentation:_ The article is partly presented at the 7th EURETINA Congress in Monte Carlo 17–20 May, 2007 RIGHTS AND PERMISSIONS Reprints and permissions ABOUT THIS ARTICLE CITE THIS

ARTICLE Lu, N., Wang, NL., Wang, G. _et al._ Vitreous surgery with direct central retinal artery massage for central retinal artery occlusion. _Eye_ 23, 867–872 (2009).

https://doi.org/10.1038/eye.2008.126 Download citation * Received: 15 June 2007 * Revised: 31 March 2008 * Accepted: 31 March 2008 * Published: 16 May 2008 * Issue Date: April 2009 * DOI:

https://doi.org/10.1038/eye.2008.126 SHARE THIS ARTICLE Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content: Get shareable link Sorry, a shareable link is not

currently available for this article. Copy to clipboard Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative KEYWORDS * CRAO * central retinal artery massage * visual acuity *

vitreous surgery