Conditional teleportation of quantum-dot spin states

- Select a language for the TTS:

- UK English Female

- UK English Male

- US English Female

- US English Male

- Australian Female

- Australian Male

- Language selected: (auto detect) - EN

Play all audios:

ABSTRACT Among the different platforms for quantum information processing, individual electron spins in semiconductor quantum dots stand out for their long coherence times and potential for

scalable fabrication. The past years have witnessed substantial progress in the capabilities of spin qubits. However, coupling between distant electron spins, which is required for quantum

error correction, presents a challenge, and this goal remains the focus of intense research. Quantum teleportation is a canonical method to transmit qubit states, but it has not been

implemented in quantum-dot spin qubits. Here, we present evidence for quantum teleportation of electron spin qubits in semiconductor quantum dots. Although we have not performed quantum

state tomography to definitively assess the teleportation fidelity, our data are consistent with conditional teleportation of spin eigenstates, entanglement swapping, and gate teleportation.

Such evidence for all-matter spin-state teleportation underscores the capabilities of exchange-coupled spin qubits for quantum-information transfer. SIMILAR CONTENT BEING VIEWED BY OTHERS

PROBABILISTIC TELEPORTATION OF A QUANTUM DOT SPIN QUBIT Article Open access 06 May 2021 ADIABATIC QUANTUM STATE TRANSFER IN A SEMICONDUCTOR QUANTUM-DOT SPIN CHAIN Article Open access 12

April 2021 FLOQUET-ENHANCED SPIN SWAPS Article Open access 09 April 2021 INTRODUCTION Quantum teleportation1 is an exquisite example of the power of quantum information transfer.

Teleportation has been demonstrated in many experimental quantum information processing platforms2,3,4,5,6,7, and it is an essential tool for quantum error correction8, measurement-based

quantum computing9, and quantum gate teleportation10. However, quantum teleportation has not previously been demonstrated in quantum-dot spin qubits. Separating entangled pairs of spins to

remote locations, as required for quantum teleportation, has previously presented the main challenge to teleportation in quantum dots. Here, we overcome this challenge using a recently

demonstrated technique to distribute entangled spin states via Heisenberg exchange11. This technique does not involve the motion of electrons, greatly simplifying the teleportation

procedure. Our teleportation method also leverages Pauli spin blockade, a unique feature of electrons in quantum dots, to generate and measure entangled pairs of spins. We combine these

concepts to perform conditional teleportation in a system of four GaAs quantum-dot spin qubits. Our data are consistent with conditional teleportation of quantum-dot spin states,

entanglement swapping, and gate teleportation. Entanglement swapping12 goes beyond teleportation of single-qubit states to create entanglement between uncorrelated particles via

measurements, and demonstrations of entanglement swapping in matter qubits are rare13,14. Our technique is fully compatible with all gate-defined quantum-dot types, including Si quantum

dots. Although we use coherent spin-state transfer via Heinseberg exchange11 to distribute entangled pairs of spins, other methods to create long-range-entangled states of spins including

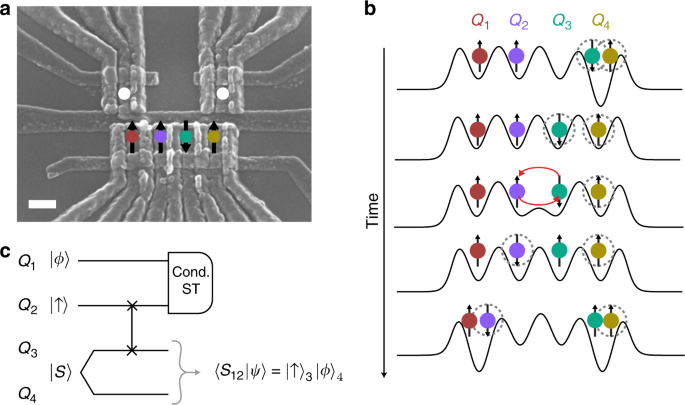

tunneling15,16,17 and coupling via superconducting resonators18 could be used as well. RESULTS DEVICE DESCRIPTION We implement our teleportation method in a four-qubit quantum processor,

which consists of a quadruple quantum dot fabricated in a GaAs/AlGaAs heterostructure [Fig. 1a]. Because the ground state wavefunction of two electrons has the spin-singlet configuration,

initialization of two spins in a single quantum dot automatically generates an entangled pair of spins19,20. Furthermore, spin-to-charge conversion via Pauli spin blockade19,21 enables rapid

single-shot measurement of pairs of electron spins in the \(\{\left|S\right\rangle ,\left|T\right\rangle \}\) basis, where \(\left|T\right\rangle\) is any one of the triplet states

\(\{\left|\uparrow \uparrow \right\rangle ,\frac{1}{\sqrt{2}}\left(\left|\uparrow \downarrow \right\rangle +\left|\downarrow \uparrow \right\rangle \right),\left|\downarrow \downarrow

\right\rangle \}\). We therefore configure the quadruple quantum dot as two pairs of spins to facilitate teleportation. Spins 1 and 2 form the left pair, and spins 3 and 4 form the right

pair. We achieve separation and distribution of entangled pairs of spins through coherent spin-state transfer based on Heisenberg exchange11. To transfer a spin state from one electron to

another, we induce exchange coupling between electrons by applying a voltage pulse to the barrier gate between them [Fig. 1b]22,23. Because exchange coupling generates a SWAP operation, this

procedure interchanges the two states. This procedure can be repeated for different pairs of spins to enable long-distance spin-state transfer. Importantly, exchange-based spin swaps

preserve entangled states11. CONDITIONAL TELEPORTATION PROTOCOL Figure 1c shows the quantum circuit for our procedure, which can conditionally teleport an arbitrary state \(\left|\phi

\right\rangle\) from dot 1 to dot 4. We prepare qubit 2 in the \(\left|\uparrow \right\rangle\) state, and it is used later for readout, as discussed further below. We generate the

Einstein-Podolsky-Rosen (EPR) pair between qubits 3 and 4 by loading two electrons into the right-most dot via electrical exchange with reservoirs. We then separate the two electrons via

tunneling. After a SWAP gate on qubits 2 and 3, the EPR pair resides in qubits 2 and 4. To teleport \(\left|\phi \right\rangle\) from qubit 1 to qubit 4, we project the left pair of qubits

onto the \(\{\left|S\right\rangle ,\left|T\right\rangle \}\) basis via diabatic charge transfer into the outer dots11 [Fig. 1b]. Our measurements in the \(\{\left|S\right\rangle

,\left|T\right\rangle \}\) basis can only distinguish \(\left|S\right\rangle =\left|{\Psi }^{-}\right\rangle\) from the other Bell states \(\left|{\Psi }^{+}\right\rangle\), \(\left|{\Phi

}^{+}\right\rangle\), or \(\left|{\Phi }^{-}\right\rangle\), which are linear combinations of the triplet states. In this case, therefore, successful teleportation requires obtaining a

singlet in the left pair. To verify teleportation, we also project the right pair, using either diabatic or adiabatic charge transfer (see “Methods”). The utility of quantum teleportation

lies in its ability to transmit unknown quantum states. Usually, teleportation of unknown states is experimentally demonstrated by verifying teleportation of a complete set of single-qubit

basis states2 or through process tomography5. Because our four-qubit device does not incorporate a micromagnet or antenna for magnetic resonance, we are not able to prepare superposition

states of single spins. Therefore, to illustrate the operation of the teleportation procedure, we first teleport a classical spin state from qubit 1 to qubit 4. Later, we demonstrate

entanglement swapping in our four-qubit processor, which conclusively demonstrates non-local manipulation of quantum states via measurements. In the future, quantum state tomography will be

required to establish that the teleportation fidelity exceeds the classical bound, as discussed below. To demonstrate the basic operation of our teleportation method using \(\left|\phi

\right\rangle =\left|\uparrow \right\rangle\), we prepare qubits 3 and 4 in a spin singlet [Fig. 2a]. Qubits 1 and 2 are prepared in the \(\left|{\psi }_{12}\right\rangle ={\left|\phi

\right\rangle }_{1}{\left|\uparrow \right\rangle }_{2}={\left|\uparrow \right\rangle }_{1}{\left|\uparrow \right\rangle }_{2}\) state by electrical exchange with the reservoirs (see

“Methods”). After the SWAP operation, if the left pair projects onto \(\left|{S}_{12}\right\rangle\), qubit 4 should be identically \(\left|\uparrow \right\rangle\)1. Because qubit 3 has the

\(\left|\uparrow \right\rangle\) state (a result of the earlier SWAP operation), the right pair should be in the \(\left|{\psi }_{34}\right\rangle ={\left|\uparrow \right\rangle

}_{3}{\left|\phi \right\rangle }_{4}={\left|\uparrow \right\rangle }_{3}{\left|\uparrow \right\rangle }_{4}\) state, and measuring a singlet on the left pair should perfectly correlate with

measuring a triplet on the right pair. Figure 2b displays a joint histogram of 65, 536 single-shot measurements on both pairs of qubits for the teleport operation discussed above. Figure 2c

shows the extracted probabilities for the different outcomes. Our measurements closely match the predicted probabilities, as shown in Fig. 2d (see “Methods”). Figure 2e shows a prediction

including known sources of experimental error, including readout fidelity, relaxation during readout, state preparation error, charge noise, and hyperfine fields, and this prediction matches

the observed data closely. We discuss these errors further below. We have also performed similar experiments with qubit 1 prepared in a mixed state (Supplementary Fig. 1), and the results

are consistent with our expectations. To verify conditional teleportation of the classical state, we perform an exchange gate on qubits 3 and 4 following the teleport [Fig. 3a]. In the case

of successful teleportation, qubits 3 and 4 should have the \(\left|{\psi }_{34}\right\rangle ={\left|\uparrow \right\rangle }_{3}{\left|\uparrow \right\rangle }_{4}\) state, and the

exchange gate should have no effect. Indeed, after measuring a singlet on the left pair, we do not observe significant exchange oscillations on the right pair, but after measuring a triplet

on the left pair, we do observe exchange oscillations on the right pair [Fig. 3a]. As shown in Supplementary Fig. 2, eliminating the SWAP operation between qubits 2 and 3 or preparing a

product state, instead of an EPR pair, on the right side, largely eliminate the conditional effect, consistent with our simulations (Supplementary Fig. 3). These data demonstrate that both

the EPR pair and the SWAP operation are critical for teleportation, as expected. The circuit of Fig. 2a can also teleport the state of qubit 3 to qubit 2, depending on the result of the

right-pair measurement. To verify that teleportation can also occur from qubit 3 to qubit 2, we switched the order of measurements and performed the variable exchange gate on the left pair

of qubits [Fig. 3b]. In this case, we observe that the oscillations on the left pair depend on the state of the right pair. Again, removing the SWAP operation or the EPR pair significantly

eliminates the conditional effect (Supplementary Fig. 2). We have performed simulations (see “Methods”), which include known sources of error, that match our observed data closely, as shown

in Supplementary Fig. 3. Our simulations reproduce the weak residual oscillations in _p_(_S_L∣_S_R) and _p_(_S_R∣_S_L) (Fig. 3), which likely result from an imperfect SWAP operation and

readout errors. Supplementary Fig. 4 shows the expected ideal results for these measurements in the absence of any errors. CONDITIONAL ENTANGLEMENT SWAPPING AND GATE TELEPORTATION Having

illustrated the basic operation of the teleport procedure, we now present evidence for conditional entanglement swapping, which confirms that the four-qubit processor indeed performs

non-local coherent manipulation of quantum information using measurements [Fig. 4a]. Entanglement swapping12 uses teleportation to generate entanglement between uncorrelated particles via

measurements. In this case, we prepare the EPR state between qubits 1 and 2 via a \(\sqrt{\,\text{SWAP}\,}\) gate, starting from the \({\left|\downarrow \right\rangle }_{1}{\left|\uparrow

\right\rangle }_{2}\) state. This process generates the entangled state \(\frac{1}{\sqrt{2}}\left(\left|{S}_{12}\right\rangle -i\left|{T}_{0,12}\right\rangle \right)\), where

\(\left|{T}_{0}\right\rangle =\frac{1}{\sqrt{2}}\left(\left|\uparrow \downarrow \right\rangle +\left|\downarrow \uparrow \right\rangle \right)\). At the same time, we prepare a separated

singlet between qubits 3 and 4. Before teleportation, we evolve the separated singlet in its local hyperfine gradient Δ_B_34 for a variable time _t_. This evolution generates an effective

_z_-rotation on qubit 4 relative to qubit 3 by an angle _θ_ = _g__μ_BΔ_B_34_t_/_ℏ_, where _g_ is the electron _g_ factor in GaAs, and _μ_B is the Bohr magneton. The _z_-rotation on qubit 4

coherently rotates the joint state of qubits 3 and 4 to \(\cos (\theta /2+\pi /4)\left|S\right\rangle +\exp (-i\pi /2)\sin (\theta /2+\pi /4)\left|{T}_{0}\right\rangle\)19,20. During this

evolution time, qubits 3 and 4 remain maximally entangled. After a SWAP gate between qubits 2 and 3, qubits 1 and 3 are entangled, and qubits 2 and 4 are entangled. After projection to a

singlet on the right side, entanglements have been swapped, because the entangled state of qubit 4 is teleported to qubit 1. Qubits 1 and 2, which were not entangled immediately before the

measurement, become entangled, provided qubits 3 and 4 project onto the singlet state. Moreover, the coherent singlet–triplet evolution that occurred on qubits 3 and 4 should appear on

qubits 1 and 2, given a singlet outcome on the right pair (see Supplementary Note 1). To verify entanglement swapping, we measure the left pair of qubits by adiabatic charge transfer19,20

(see “Methods”) following another \(\sqrt{{\rm{SWAP}}}\) gate. In the case of successful entanglement swapping, the final \(\sqrt{{\rm{SWAP}}}\) gate preserves the coherence of the

teleported state against the effects of hyperfine fluctuations during readout. To observe the anticipated oscillations, we sweep _t_, which controls the _z_ rotation on qubit 4, from 0 to

127 ns, in steps of 1 ns. For each time interval, we implement the quantum circuit shown in Fig. 4a and record a single-shot measurement of both pairs of qubits, and we average this set of

measurements 256 times. Figure 4b shows the average of one such set of measurements. No oscillations are visible in the unconditioned singlet probability of the left pair _p_(_S_L). However,

prominent oscillations are visible in the probability of a singlet on the left given a singlet on the right _p_(_S_L∣_S_R) and also in _p_(_S_L∣_T_R), in good agreement with our simulations

[Fig. 4b and Supplementary Fig. 6]. These oscillations demonstrate conditional entanglement swapping. Because the nuclear hyperfine fields fluctuate in time, we repeat this set of

measurements 256 times, and the entire data set is shown in Supplementary Fig. 7. In between each set, we also perform additional measurements to determine the hyperfine gradients between

dots 1 and 2 (Δ_B_12) and dots 3 and 4 (Δ_B_34) (Supplementary Fig. 8)20. In total, each repetition takes about one second. For each repetition, we extract the oscillation frequency by

taking a fast Fourier transform of the data (see “Methods” and Supplementary Fig. 7). Figure 4c shows the extracted oscillation frequency that appears on qubits 1 and 2 after entanglement

swapping in addition to the frequencies corresponding to Δ_B_12 and Δ_B_34, which were measured concurrently with the teleportation. The observed oscillation frequency measured on qubits 1

and 2 clearly matches the measured hyperfine gradient Δ_B_34. Because Δ_B_12 and Δ_B_34 result from independent nuclear spin ensembles, they evolve differently in time. We note the good

agreement between the time evolution of the oscillation frequency after entanglement swapping and the gradient Δ_B_34. To confirm that the singlet–triplet oscillations on the left pair

result from entanglement swapping, we have performed additional measurements which omit the SWAP operation between qubits 2 and 3 (Supplementary Fig. 5). These data show no conditional

effect. Therefore, the observed oscillations on qubits 1 and 2 in Fig. 4b result entirely from the coherent evolution between entangled states of qubits 3 and 4, together with the SWAP gate

and Bell-state measurement. This demonstration of entanglement swapping using our four-qubit processor confirms that we can perform non-local coherent manipulation on entangled states of the

form \(\cos (\theta /2)\left|S\right\rangle +\exp ({\!}\pm {\!}i\pi /2)\sin (\theta /2)\left|{T}_{0}\right\rangle\) by quantum measurements. A similar circuit [Fig. 4d] also implements a

simple example of conditional quantum gate teleportation10, provided that we post-select on the left-side measurements, instead of the right side. In this case, the EPR pair initially

consists of qubits 3 and 4, and we teleport qubit 1 to qubit 4. A unitary gate _U_ (the same _z_ rotation discussed above), which is applied to one member of the EPR pair before

teleportation, appears on qubit 4 after teleportation. The initial entangled state of qubits 1 and 2 is \(\left|{\psi }_{12}\right\rangle =\frac{1}{\sqrt{2}}\left(\left|{S}_{12}\right\rangle

-i\left|{T}_{0,12}\right\rangle \right)\). Following the SWAP and conditional teleportation of qubit 1 to qubit 4, qubits 3 and 4 have the state \(\left|{\psi }_{34}\right\rangle

=({\mathbb{1}}\otimes U\cdot {R}_{z}(\pi /2))\left|{\psi }_{12}\right\rangle\), and _U_ has been applied to qubit 4. The added _z_ rotation on qubit 4 occurs because of the additional

\(\sqrt{{\rm{SWAP}}}\) and measurement via adiabatic charge transfer on the left side [Fig. 4d]. We measure the right pair of qubits via diabatic charge transfer to verify teleportation

[Fig. 4e]. The unconditioned data show very weak oscillations, likely due to an imperfect SWAP gate11. Post-selecting based on singlet outcomes on the left side yields prominent oscillations

in time, consistent with our simulations. The extracted oscillation frequency versus repetition number agrees well with the data from Fig. 4c, as shown in Fig. 4f. The fidelity of the

teleport operation is limited by readout fidelity, relaxation during readout, state preparation, charge noise, and the hyperfine coupling between the electron spins and Ga and As nuclear

spins in the substrate. Readout fidelity and relaxation both limit the probability that we will correctly measure the Bell state of one of the EPR pair and the qubit to be teleported.

Readout fidelities are 0.93 for the left pair and 0.87 for the right pair (see “Methods” and Supplementary Figs. 11 and 12). State preparation of the EPR pair also affects the teleport

operation. We estimate the probability that we correctly prepare the singlet state in dots 3–4 is 0.89, based on our experimental characterization of the loading process [Supplementary Fig.

10b]. Charge noise causes dephasing of the SWAP operation, and the nuclear hyperfine field limits the fidelity of the SWAP operation that we use to transmit the entangled pair of

electrons11. The simulations shown in Figs. 2 and 4 and Supplementary Figs. 1, 3, and 5 include all of these effects, in addition to the classical-state initialization error (see “Methods”)

where appropriate. To assess the fidelity of the teleport operation itself for classical states, we simulated the circuit shown in Fig. 2a, assuming perfect state preparation of the left

pair, but including all other sources of error. Based on our simulations, we expect that the spin in dot 4 will be in the \(\left|\uparrow \right\rangle\) state after the teleport with a

probability of about 0.9, given a singlet on the left pair. In the presence of realistic hyperfine gradients (tens of MHz) and exchange strengths (several hundred MHz), we estimate that

readout errors contribute the majority of the error. Assuming perfect preparation of a separated singlet state, our simulations suggest that the fidelity of the entanglement swap [Fig. 4a]

on a singlet state can be ~0.7, provided that the state is allowed to evolve in the presence of a quasi-static magnetic gradient to undo the coherent singlet–triplet evolution incurred

during the SWAP operation in the presence of a gradient11 (see Supplementary Note 3). In this case, readout errors, state preparation errors of the EPR pair, and errors in the SWAP gate due

to the magnetic gradient all contribute to the overall error. The average classical limit for teleporting entangled states of the type we use in this experiment is 2/324 (see Supplementary

Note 2). By fitting the data of Fig. 4b (see “Methods”, Supplementary Note 3, and Supplementary Fig. 9), we can also extract a maximum singlet teleportation probability of 0.71 ± 0.04, which

compares favorably with the classical limit, although further research involving quantum state tomography is required to provide definitive proof. This value also agrees with our simulated

fidelity and indicates that a classical explanation for our data is extremely unlikely (see Supplementary Notes 1 and 4). DISCUSSION This teleportation protocol is fully compatible with all

gate-defined quantum-dot types, including Si quantum dots. Indeed, this teleportation protocol will work best with small magnetic gradients, as can be achieved with Si qubits. In large

gradients, resonant approaches25,26 or dynamically corrected gates27 can still generate high-fidelity SWAP operations. State preparation errors can be suppressed by improving the coupling

between the quantum dots and the reservoirs, and readout errors can be minimized by optimizing the position of the sensor quantum dots. We discuss the potential application of this technique

to Si qubits in “Methods”. As mentioned above and discussed further in “Methods”, the conditional quantum teleportation protocol we have developed is compatible with arbitrary qubit states.

Deterministic quantum teleportation of arbitrary quantum states can also be realized with measurements of each qubit in the computational basis, together with CNOT28,29,30 and single-qubit

gates31, which will enable complete measurements in the Bell-state basis32. Fast spin measurements together with real-time adaptive control33 could be used to complete the deterministic

state transfer process. The evidence we have presented for conditional state teleportation, entanglement swapping, and gate teleportation adds time-honored capabilities to the library of

quantum information processing techniques available to spin qubits in quantum dots. Our results also highlight the potential of exchange-coupled spin chains for quantum information transfer.

We envision that teleportation will be useful for the creation and manipulation of long-range entangled states and for error correction in quantum-dot spin qubits. As spin-based quantum

information processors scale up, maintaining high-connectivity between spins will be critical, and quantum teleportation also opens an essential pathway toward achieving this goal. In many

ways, spin qubits in quantum dots are an ideal platform for quantum teleportation, because they offer a straightforward means of generating and measuring entangled states of spins. As a

result, we expect that quantum teleportation will find significant use in future spin-based quantum information processing efforts. METHODS DEVICE The four-qubit processor is a quadruple

quantum dot fabricated on a GaAs/AlGaAs hetereostructure with a two-dimensional electron gas located 91 nm below the surface. The Si-doped region has vertical width of 14.3 nm, centered 24

nm below the top surface of the wafer. In this region, the dopant density is 3 × 1018 cm−3. The two-dimensional electron gas density _n_ = 1.5 × 1011 cm−2 and mobility _μ_ = 2.5 × 106 cm2

V−1 s−1 were measured at _T_ = 4K. Quantum dot fabrication proceeds as follows. Following ohmic contact fabrication via a standard metal stack and anneal, 10 nm of Al2O3 was deposited via

atomic layer deposition. Three layers of overlapping aluminum gates34,35 were defined via electron beam lithography, thermal evaporation, and liftoff. The gate layers are isolated by a thin

native oxide layer. The active area of the device is also covered with a grounded top gate. This is likely to screen the effects of disorder imposed by the oxide. Empirically, we find that

overlapping gates are essential for the exchange pulses we use in this work. The quadruple dot is cooled in a dilution refrigerator to a base temperature of ~10 mK. An external magnetic

field _B_ = 0.5 T is applied in the plane of the semiconductor surface perpendicular to the axis connecting the quantum dots. Using virtual gates36,37, we tune the device to the

single-occupancy regime. INITIALIZATION To load the \(\left|{T}_{+,12}\right\rangle ={\left|\uparrow \right\rangle }_{1}{\left|\uparrow \right\rangle }_{2}\) state, we exchange electrons

with the reservoirs in the (1, 1) charge configuration20. Both the magnetic field and temperature limit the fidelity of this process (Supplementary Fig. 10). We simulated the initialization

fidelity by calculating the time-dependent populations of all relevant spin-states during the loading procedure. This simulation process is detailed in ref. 38. We assumed an electron

temperature of 75 mK and a magnetic field of 0.5 T [Supplementary Fig. 10a]. This is broadly consistent with the electron temperatures we have measured in our setup, which range from 50 to

100 mK. Based on these simulations, we estimate that this state preparation fidelity is ~0.7. The simulations presented here take this preparation error into account. In principle,

increasing the magnetic field should improve the fidelity of the \(\left|{T}_{+}\right\rangle\) loading process. Empirically, however, we did not observe a substantial enhancement with

fields up to 1 T, as has previously been observed38. We suspect that unintentional dynamic nuclear polarization significantly modifies the magnetic field at the location of each dot. To load

a separated singlet state, we exchange electrons with the reservoirs in the (0,2) charge configuration20. We initialize the right pair of electrons in dot 4 as a singlet with 0.89

probability for a load time of 2 μs [Supplementary Fig. 10b]. This could be improved in the future by optimizing the coupling of the electrons to the source and drain reservoirs. Based on

simulations of the Landau–Zener tunneling process to separate the electrons, we estimate that separating the singlet state incurs only a few percent error. We can initialize either pair of

electrons as \(\left|\downarrow \uparrow \right\rangle\) or \(\left|\uparrow \downarrow \right\rangle\) by adiabatically separating a singlet state20. The orientation of the two spins in

this product state depends on the orientation of the local hyperfine field. EXCHANGE We induce exchange coupling between pairs of qubits by applying a voltage pulse to the barrier between

the respective pair of dots22,23. Exchange coupling generated in this way is first-order insensitive to charge noise associated with the plunger gates. Barrier-gate pulses are accompanied by

compensation pulses on the plunger gates to keep the dot chemical potentials fixed. For the exchange gates used in this work, we used a combination of barrier-22,23, and tilt-controlled19

exchange. Empirically, we found that using this combination helps us to boost the exchange strength and improves the fidelity of the SWAP operation. All exchange pulses are optimized at the

same tuning used to acquire all data in this work with one electron in each dot. We do not observe that pulsing exchange between two spins generates spurious enhanced exchange coupling

elsewhere in the array. READOUT Diabatic charge transfer into the outer dots projects the spin state of the separated pair onto the \(\{\left|S\right\rangle ,\left|T\right\rangle \}\)

basis19,20. Adiabatic charge transfer into the outer dots maps either \(\left|\downarrow \uparrow \right\rangle\) or \(\left|\uparrow \downarrow \right\rangle\) to \(\left|S\right\rangle\),

depending on the sign of the local magnetic gradient, and it maps all other spin states to triplets19,20. Here, “diabatic” or “adiabatic” refer to the speed with which the electrons are

recombined relative to the size of the hyperfine gradient. We represent readout by diabatic charge transfer with an “ST” in figures, and we represent readout by adiabatic charge transfer

with a “↓↑” in figures. When used to verify teleportation, diabatic charge transfer can only verify teleportation when \(\left|\phi \right\rangle =\left|\uparrow \right\rangle\). In

principle, however, readout by adiabatic charge transfer could be used to measure qubit 4 in its computational basis. If Δ_B_34 were such that \({\left|\uparrow \right\rangle

}_{3}{\left|\downarrow \right\rangle }_{4}\) were the ground state, adiabatic charge transfer would map \({\left|\uparrow \right\rangle }_{3}{\left|\downarrow \right\rangle }_{4}\) to a

singlet, and \({\left|\uparrow \right\rangle }_{3}{\left|\uparrow \right\rangle }_{4}\) to a triplet. Together with tomographic rotation pulses, such a measurement would enable verification

of teleportation of arbitrary states. In addition to conventional spin-blockade readout on both pairs of electrons, we use a shelving mechanism39 to enhance the readout visibility. Using the

two sensor quantum dots configured for rf-reflectometry (Fig. 1)21, we achieve single-shot readout with integration times of 4 μs on the left side and 6 μs on the right side and fidelities

of 0.93 and 0.87, respectively. Relaxation times during readout were 65 μs and 48 μs on the left and right sides. Supplementary Fig. 12a, b show the experimentally measured curves

demonstrating the relaxation during readout for both pairs of electrons. Supplementary Figure 11a, b show fits to the readout histograms using Eqs. (1) and (2) in ref. 21 for each pair of

qubits. In all teleportation measurements, both pairs of qubits are measured sequentially in the same single-shot sequence. To determine the probabilities for the four different

possibilities for joint measurements of both pairs, we fit the total measurement histogram for each pair separately. We determine the threshold for each pair by choosing the signal level

that maximizes the visibility21. We then use these two thresholds to divide the probability distribution into quadrants. The overall probability is normalized, and we calculate the net

probability in each quadrant. To eliminate any state-dependent crosstalk between qubit pairs during readout, we reload the first pair of electrons that we measure as an

\(\left|S\right\rangle\) before reading out the next pair for the data in Figs. 2 and 3. For the data in Fig. 4, we additionally implemented a voltage ramp to bring each pair of electrons

back to the (1,1) idling point immediately after readout. We empirically find that these procedures eliminate crosstalk during readout. The data in Supplementary Fig. 5 demonstrate that

there is negligible readout or control crosstalk in our system. Improvements to readout can be made by repositioning the sensor quantum dots for maximum differential charge sensitivity to

achieve readout errors of <0.01 in integration times of <1 μs, as has previously been demonstrated in quantum dot spin qubits33,40. SIMULATION Our simulations include errors

associated with state preparation, readout fidelity, relaxation during readout, charge noise, and the fluctuating magnetic gradient. We approximate singlet loading error by creating a

two-electron state $$\left|\tilde{S}\right\rangle ={s}_{1}\left|S\right\rangle +{s}_{2}\left|{T}_{0}\right\rangle +{s}_{3}\left|{T}_{+}\right\rangle +{s}_{4}\left|{T}_{-}\right\rangle ,$$

(1) where ∣_s_1∣2 = _f_s, and ∣_s_2∣2 = ∣_s_3∣2 = ∣_s_4∣2 = (1 − _f_s)/3. Also, \(\left|{T}_{-}\right\rangle =\left|\downarrow \downarrow \right\rangle\), and \(\left|{T}_{+}\right\rangle

=\left|\uparrow \uparrow \right\rangle\). _f_s = 0.89 is the singlet load fidelity. All coefficients are given random phases for each realization of the simulation. To simulate loading error

during adiabatic separation of electrons, we set $$\left|\tilde{G}\right\rangle ={s}_{1}\left|\downarrow \uparrow \right\rangle +{s}_{2}\left|\uparrow \downarrow \right\rangle

+{s}_{3}\left|{T}_{+}\right\rangle +{s}_{4}\left|{T}_{-}\right\rangle ,$$ (2) where the coefficients are the same as described above. We use the same coefficients, because the singlet

initialization error dominates the error in this process. We also allow the orientation of the spins in this state to change between runs of the simulation as the hyperfine gradient changes.

We approximate the \(\left|{T}_{+}\right\rangle\) loading error by simulating the loading process as described in ref. 38. We directly extract the population coefficients of the other three

two-electron spin states. We create a state which is a sum of all two-electron spin states: $$\left|\tilde{{T}_{+}}\right\rangle ={t}_{1}\left|S\right\rangle

+{t}_{2}\left|{T}_{0}\right\rangle +{t}_{3}\left|{T}_{+}\right\rangle +{t}_{4}\left|{T}_{-}\right\rangle ,$$ (3) where ∣_t__i_∣2 is determined as discussed above. We assign random phases to

each of the coefficients during each realization of the simulation. To simulate the spin-eigenstate teleport operation, we set the initial state of the four-qubit system as $$|{\psi

}_{i}\rangle =|{\tilde{T}}_{+,12}\rangle \otimes |{\tilde{S}}_{34}\rangle .$$ (4) To simulate the mixed-state and entangled-state teleport operations, we set the initial state as

$$\left|{\psi }_{i}\right\rangle =|{\tilde{G}}_{12}\rangle \otimes \left|{\tilde{S}}_{34}\right\rangle .$$ (5) We incorporate charge noise and the hyperfine magnetic field and their effects

on the SWAP operation by directly solving the Schrödinger equation for a four spin system. We generated a simulated SWAP operation from the following Hamiltonian:

$${H}_{{\rm{S}}}=\frac{h}{4}{J}_{23}({\sigma }_{x,2}\otimes {\sigma }_{x,3}+{\sigma }_{y,2}\otimes {\sigma }_{y,3}+{\sigma }_{z,2}\otimes {\sigma }_{z,3})$$ (6) $$+\, \frac{g{\mu

}_{{\rm{B}}}}{2}\mathop{\sum }\limits_{k = 1}^{4}{B}_{k}{\sigma }_{z,k}$$ (7) We assume a fixed exchange coupling of _J_23 of 250 MHz between spins 2 and 3, and we adjust the time _T__S_ for

the SWAP operation to give a _π_ pulse. These parameters correspond closely to the actual experiments. To account for charge noise, we allow the value of _J_23 to fluctuate by 1% between

simulation runs. We arrive at this level of charge noise via the expression \(Q=\frac{J}{\sqrt{2}\pi \delta J}\)41, where \(\frac{\delta J}{J}\) is the fractional electrical noise, using the

measured quality factor of 21. For the spin-eigenstate simulation, we set the local nuclear magnetic fields _B__k_ of spin _k_ to be (−1, 6, −4, 0) MHz \(\times \frac{2h}{g{\mu

}_{{\rm{B}}}}\) for the qubits. We also include for each qubit the overall background field of 0.5 T. We allow the nuclear field at each site to fluctuate according to a normal distribution

with standard deviation of 12 MHz for qubits 1 and 2 and 10 MHz for qubits 3 and 4. The field and fluctuations are adjusted to improve the agreement between the simulations in Supplementary

Figs. 2 and 3. We empirically observe that the hyperfine fields fluctuate during the course of a given data-taking run, and they can even switch sign. Because we do not know a-priori what

the hyperfine fields will be, it seems reasonable to treat them as fit parameters, especially since the chosen values fall well within the expected range. The overall evolution of the

four-qubit system during the SWAP operation is given by the following propagator: \({S}_{23}=\exp \left(\frac{-i{H}_{{\rm{S}}}{T}_{{\rm{S}}}}{\hslash }\right)\). The voltage pulses in our

setup have finite rise times, which cause the four-qubit system to evolve under the magnetic gradient in the absence of exchange. To simulate this effect, we define

$${H}_{{\rm{B}}}=\frac{g{\mu }_{{\rm{B}}}}{2}\mathop{\sum }\limits_{k = 1}^{4}{B}_{k}{\sigma }_{z,k}.$$ (8) Under this Hamiltonian, the wavefunction evolves according to the following

propagator: \({U}_{{\rm{B}}}=\exp \left(\frac{-i{H}_{{\rm{B}}}{T}_{{\rm{B}}}}{\hslash }\right)\). In the experiment, all pulses are convolved in software with a Gaussian of width 2 ns before

delivery to the qubits, so we set _T_B = 2 ns. To simulate the spin-eigenstate teleport experiment, the simulated final state after the teleport operation is thus \(\left|\psi \right\rangle

={U}_{{\rm{B}}}{S}_{23}{U}_{{\rm{B}}}\left|{\psi }_{i}\right\rangle\). For the simulations presented in Supplementary Figs. 1 and 2, we also accounted for imperfections in our pulsing by

allowing for the singlet–triplet state vector to rotate slightly during pulses which should ideally be perfectly diabatic. For example, suddenly separating a singlet is usually accompanied

by some evolution toward the ground state of the hyperfine field, because the pulse is not perfectly sudden. We account for this by allowing the effective singlet–triplet state vector to

rotate by 7° toward the ground state of the hyperfine field during sudden separation of the singlet and by −7° during readout via diabatic charge transfer. This rotation is implemented as a

rotation about the _y_ axis in the effective _S_ − _T_0 subspace for each pair of qubits. The _y_ axis is defined by the usual _S_ − _T_0 Hamiltonian: _J__σ__z_ + Δ_B__σ__x_. The rotation

angle of 7° was chosen to match an additional control data set in which we adiabatically measured a singlet prepared via diabatic separation. Ideally, this measurement yields a singlet

probability of 0.5. In practice, the measured singlet probability is slightly larger than this due to pulse errors, and 7 degrees was chosen to match the observed return probability. To

compute the expected probabilities in Fig. 2d, e, we calculate all pairs of two-qubit correlators: _C__α_,_β_ = 〈_ψ_∣_α_ ⊗ _β_〉〈_α_ ⊗ _β_∣_ψ_〉, where _α_ (qubits 1 and 2) and _β_ (qubits 3

and 4) can be any of \(\{\left|S\right\rangle ,\left|{T}_{+}\right\rangle ,\left|{T}_{0}\right\rangle ,\left|{T}_{-}\right\rangle \}\). We calculate the probabilities in Fig. 2 as

$${P}_{{\rm{SS}}}={C}_{\left|S\right\rangle ,\left|S\right\rangle },$$ (9) $${P}_{{\rm{TT}}}=\sum \limits_ {^{\alpha \ne |S\rangle} _{\beta \ne |S\rangle}}{C}_{\alpha ,\beta },$$ (10)

$${P}_{{\rm{ST}}}=\sum _{\beta \ne \left|S\right\rangle }{C}_{\left|S\right\rangle ,\beta },$$ (11) $${P}_{{\rm{TS}}}=\sum _{\alpha \ne \left|S\right\rangle }{C}_{\alpha

,\left|S\right\rangle }.$$ (12) To simulate readout errors, we define the \({g}_{{\rm{L}}({\rm{R}})}=1-\exp (-{t}_{{\rm{m}}}^{{\rm{L}}({\rm{R}})}/{T}_{1}^{{\rm{L}}({\rm{R}})})\) to be the

probabilities that the triplet state on the left (right) side will relax to the singlet during readout. Here \({t}_{{\rm{m}}}^{{\rm{L}}({\rm{R}})}\) is the measurement time, and

\({T}_{1}^{{\rm{L}}({\rm{R}})}\) is the relaxation time, as discussed above. We also set _r_L(R) = 1 − _f_L(R) as the probability that singlet or triplet on the left (right) side will be

misidentified due to noise. Here _f_L(R) is the measurement fidelity due to random noise on the left (right) pair. The experimentally measured probabilities are

$${P}_{{\rm{SS}}}^{\prime}=(1-{r}_{{\rm{L}}}-{r}_{{\rm{R}}}){P}_{{\rm{SS}}}+{g}_{{\rm{L}}}{P}_{{\rm{TS}}}+{g}_{{\rm{L}}}{P}_{{\rm{ST}}}+{r}_{{\rm{L}}}{P}_{{\rm{TS}}}+{r}_{{\rm{R}}}{P}_{{\rm{ST}}},$$

(13)

$${P}_{{\rm{ST}}}^{\prime}=(1-{r}_{{\rm{L}}}-{r}_{{\rm{R}}}){P}_{{\rm{ST}}}+{g}_{{\rm{L}}}{P}_{{\rm{TT}}}-{g}_{{\rm{L}}}{P}_{{\rm{ST}}}+{r}_{{\rm{L}}}{P}_{{\rm{TT}}}+{r}_{{\rm{R}}}{P}_{{\rm{SS}}},$$

(14)

$${P}_{{\rm{TS}}}^{\prime}=(1-{r}_{{\rm{L}}}-{r}_{{\rm{R}}}){P}_{{\rm{TS}}}-{g}_{{\rm{L}}}{P}_{{\rm{TS}}}+{g}_{{\rm{L}}}{P}_{{\rm{TT}}}+{r}_{{\rm{L}}}{P}_{{\rm{SS}}}+{r}_{{\rm{R}}}{P}_{{\rm{TT}}},$$

(15)

$${P}_{{\rm{TT}}}^{\prime}=(1-{r}_{{\rm{L}}}-{r}_{{\rm{R}}}){P}_{{\rm{TT}}}-{g}_{{\rm{L}}}{P}_{{\rm{TT}}}-{g}_{{\rm{L}}}{P}_{{\rm{TT}}}+{r}_{{\rm{L}}}{P}_{{\rm{ST}}}+{r}_{{\rm{R}}}{P}_{{\rm{TS}}}.$$

(16) The displayed probabilities in Fig. 2d are \({P}_{{\rm{SS}}}^{\prime}\), \({P}_{{\rm{ST}}}^{\prime}\), \({P}_{{\rm{TS}}}^{\prime}\), and \({P}_{{\rm{TT}}}^{\prime}\). To simulate the

data shown in Fig. 3, we generate variable exchange propagators _U_12 and _U_34 using Hamiltonians analogous to Eq. (7) for exchange between qubits 1–2 and qubits 3–4. Probabilities were

calculated as described above. For example, to generate the simulations in Supplementary Fig. 3a, the final state is computed as \(\left|\psi \right\rangle

={U}_{{\rm{B}}}{U}_{34}{U}_{{\rm{B}}}{S}_{23}{U}_{{\rm{B}}}\left|{\psi }_{i}\right\rangle\). We compute all possible correlators _C__α_,_β_, where _α_ is any of \(\{\left|S\right\rangle

,\left|{T}_{+}\right\rangle ,\left|{T}_{0}\right\rangle ,\left|{T}_{-}\right\rangle \}\), and _β_ is any of \(\{\left|\downarrow \uparrow \right\rangle ,\left|{T}_{+}\right\rangle

,\left|\uparrow \downarrow \right\rangle ,\left|{T}_{-}\right\rangle \}\) and extract probabilities as discussed above. The simulated data are averaged over 1000 realizations of magnetic and

electrical noise and random state errors. We note that the ground state configuration (\(\left|\downarrow \uparrow \right\rangle\) or \(\left|\uparrow \downarrow \right\rangle\)) is allowed

to change in the simulation if the gradient changes sign due to random noise. The results of these simulations are shown in Supplementary Fig. 3, which shows the operator sequences and

initial states used to simulate the data. To simulate the data in Fig. 4, we compute the final state as \(\left|\psi \right\rangle

={S}_{12}^{1/2}{U}_{{\rm{B}}}{S}_{23}{U}_{{\rm{B}}}{S}_{12}^{1/2}{U}_{{\rm{B}}}^{{\rm{R}}}(t)\left|{\psi }_{i}\right\rangle\). Here \({U}_{{\rm{B}}}^{{\rm{R}}}(t)\) indicates that the

right-pair of qubits evolves for a variable time _t_ in their magnetic gradient Δ_B_34. We compute all possible correlators _C__α_,_β_, where _α_ is any of \(\{\left|\downarrow \uparrow

\right\rangle ,\left|{T}_{+}\right\rangle ,\left|\uparrow \downarrow \right\rangle ,\left|{T}_{-}\right\rangle \}\), and _β_ is any of \(\{\left|S\right\rangle ,\left|{T}_{+}\right\rangle

,\left|{T}_{0}\right\rangle ,\left|{T}_{-}\right\rangle \}\). For this simulation, magnetic gradients were chosen to match the observed frequencies, and the width of the hyperfine

distribution was reduced to mimic the effects of averaging for only a few seconds and to match the observed decay. For these data, exchange strengths were chosen to be 90 MHz. To simulate

the ideal results in the absence of noise in Fig. 2, Supplementary Figs. 4 and 6, we eliminated all preparation and readout errors, all noise sources, and we eliminated the 2-ns evolution

periods, which account for pulse rise times. We also eliminated the effect of magnetic gradients during the SWAP pulses. ESTIMATION OF Δ_B_ FREQUENCIES To extract the oscillation frequencies

of the data in Fig. 4 and Supplementary Fig. 8, we zero-padded each line (corresponding to an average of up to 256 single-shot repetitions of each evolution time) by 256 points and took the

absolute value of the fast Fourier transform of this averaged time series. We then found the frequency giving the peak value. To reduce the effects of noise, we rejected all repetitions

giving frequencies larger than 100 MHz. To generate the displayed frequency vs. repetition number traces, we smoothed the frequency vs. repetition series with a moving 10-point average.

APPLICABILITY TO SI SPIN QUBITS All of the necessary steps for conditional teleportation, including barrier-controlled exchange23, and readout and initialization via Pauli spin-blockade42,

have already been demonstrated in Si quantum dots. In general, we expect teleportation to work even better in Si, where magnetic gradients and noise can be reduced. One potential challenge

is the requirement for spin blockade; small valley splittings in Si can easily lift spin-blockade43. However, this challenge is easily overcome by operating the quantum dots at larger

occupation numbers where the singlet–triplet energy splitting is dominated by the orbital energy spacing44,45. Another potential complication for Si qubits is the frequent use of

micromagnets, which generate intense magnetic field gradients, for single-spin control. In particular, strong magnetic gradients make pure exchange rotations challenging. However, resonant

exchange gates25,26 or dynamically corrected gates27 can still generate high-fidelity SWAP operations in large magnetic gradients. EXTENSION TO DETERMINISTIC TELEPORTATION OF ARBITRARY

STATES Deterministic teleportation of arbitrary states requires the ability to distinguish all four Bell states and the ability to generate arbitrary input states to the teleport. Achieving

complete readout in the Bell-state basis is most easily achieved with single-qubit and CNOT gates together with single-qubit readout32. High-fidelity single-qubit31 and CNOT gates28,29,30

have already been demonstrated in Si. Single-spin readout can be achieved via Pauli spin-blockade measurements with a known ancilla spin46, as discussed in the Readout section above, and

SWAP operations. Alternatively, spin-selective tunneling47 can be used. Fast spin measurements48 together with real-time adaptive control33 could be used to complete the deterministic state

transfer process. DATA AVAILABILITY The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. REFERENCES * Bennett, C. H.,

Brassard, G., Crépeau, C., Jozsa, R., Peres, A. & Wootters, W. K. Teleporting an unknown quantum state via dual classical and Einstein-Podolsky-Rosen channels. _Phys. Rev. Lett._ 70,

1895–1899 (1993). Article ADS MathSciNet CAS PubMed MATH Google Scholar * Bouwmeester, D., Pan, J.-W., Mattle, K., Eibl, M., Weinfurter, H. & Zeilinger, A. Experimental quantum

teleportation. _Nature_ 390, 575–579 (1997). Article ADS CAS MATH Google Scholar * Riebe, M., Häffner, H., Roos, C. F., Hänsel, W. & Benhelm, J. Deterministic quantum teleportation

with atoms. _Nature_ 429, 734–737 (2004). Article ADS CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Olmschenk, S., Matsukevich, D. N., Maunz, P., Hayes, D., Duan, L.-M. & Monroe, C. Quantum

teleportation between distant matter qubits. _Science_ 323, 486–489 (2009). Article ADS CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Steffen, L., Salathe, Y., Oppliger, M., Kurpiers, P. & Baur, M.

Deterministic quantum teleportation with feed-forward in a solid state system. _Nature_ 500, 319 (2013). Article ADS CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Pfaff, W., Hensen, B. J., Bernien, H.,

van Dam, S. B. & Blok, M. S. Unconditional quantum teleportation between distant solid-state quantum bits. _Science_ 345, 532–535 (2014). Article ADS MathSciNet CAS PubMed MATH

Google Scholar * Pirandola, S., Eisert, J., Weedbrook, C., Furusawa, A. & Braunstein, S. L. Advances in quantum teleportation. _Nat. Photonics_ 9, 641 (2015). Article ADS CAS Google

Scholar * Knill, E. Quantum computing with realistically noisy devices. _Nature_ 434, 39–44 (2005). Article ADS CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Raussendorf, R., Browne, D. E. &

Briegel, H. J. Measurement-based quantum computation on cluster states. _Phys. Rev. A_ 68, 022312 (2003). Article ADS CAS Google Scholar * Gottesman, D. & Chuang, I. L. Demonstrating

the viability of universal quantum computation using teleportation and single-qubit operations. _Nature_ 402, 390–393 (1999). Article ADS CAS Google Scholar * Kandel, Y. P., Qiao, H.,

Fallahi, S., Gardner, G. C., Manfra, M. J. & Nichol, J. M. Coherent spin-state transfer via heisenberg exchange. _Nature_ 573, 553–557 (2019). Article ADS CAS PubMed Google Scholar

* Żukowski, M., Zeilinger, A., Horne, M. A. & Ekert, A. K. ‘Event-ready-detectors’ Bell experiment via entanglement swapping. _Phys. Rev. Lett._ 71, 4287–4290 (1993). Article ADS

PubMed Google Scholar * Riebe, M., Monz, T., Kim, K., Villar, A. S., Schindler, P., Chwalla, M., Hennrich, M. & Blatt, R. Deterministic entanglement swapping with an ion-trap quantum

computer. _Nat. Phys._ 4, 839–842 (2008). Article CAS Google Scholar * Ning, W., Huang, X.-J., Han, P.-R., Li, H. & Deng, H. Deterministic entanglement swapping in a superconducting

circuit. _Phys. Rev. Lett._ 123, 060502 (2019). Article ADS CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Fujita, T., Baart, T. A., Reichl, C., Wegscheider, W. & Vandersypen, L. M. K. Coherent

shuttle of electron-spin states. _npj Quantum Inf._ 3, 22 (2017). Article ADS Google Scholar * Nakajima, T., Delbecq, M. R., Otsuka, T., Amaha, S. & Yoneda, J. Coherent transfer of

electron spin correlations assisted by dephasing noise. _Nat. Commun._ 9, 2133 (2018). Article ADS PubMed PubMed Central CAS Google Scholar * Flentje, H., Mortemousque, P.-A.,

Thalineau, R., Ludwig, A. & Wieck, A. D. Coherent long-distance displacement of individual electron spins. _Nat. Commun._ 8, 501 (2017). Article ADS CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google

Scholar * Borjans, F., Croot, X. G., Mi, X., Gullans, M. J. & Petta, J. R. Resonant microwave-mediated interactions between distant electron spins. _Nature_ 577, 195–198 (2020).

Article ADS CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Petta, J. R., Johnson, A. C., Taylor, J. M., Laird, E., Yacoby, A., Lukin, M. D., Marcus, C. M., Hanson, M. P. & Gossard, A. C. Coherent

manipulation of coupled electron spins in semiconductor quantum dots. _Science_ 309, 2180–2184 (2005). Article ADS CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Foletti, S., Bluhm, H., Mahalu, D.,

Umansky, V. & Yacoby, A. Universal quantum control of two-electron spin quantum bits using dynamic nuclear polarization. _Nat. Phys._ 5, 903–908 (2009). Article CAS Google Scholar *

Barthel, C., Reilly, D. J., Marcus, C. M., Hanson, M. P. & Gossard, A. C. Rapid single-shot measurement of a singlet-triplet qubit. _Phys. Rev. Lett._ 103, 160503 (2009). Article ADS

CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Martins, F., Malinowski, F. K., Nissen, P. D., Barnes, E. & Fallahi, S. Noise suppression using symmetric exchange gates in spin qubits. _Phys. Rev. Lett._

116, 116801 (2016). Article ADS MathSciNet PubMed CAS Google Scholar * Reed, M. D., Maune, B. M., Andrews, R. W., Borselli, M. G. & Eng, K. Reduced sensitivity to charge noise in

semiconductor spin qubits via symmetric operation. _Phys. Rev. Lett._ 116, 110402 (2016). Article ADS CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Massar, S. & Popescu, S. Optimal extraction of

information from finite quantum ensembles. _Phys. Rev. Lett._ 74, 1259–1263 (1995). Article ADS MathSciNet CAS PubMed MATH Google Scholar * Nichol, J. M., Orona, L. A., Harvey, S. P.,

Fallahi, S. & Gardner, G. C. High-fidelity entangling gate for double-quantum-dot spin qubits. _npj Quantum Inf._ 3, 3 (2017). Article ADS Google Scholar * Sigillito, A. J., Gullans,

M. J., Edge, L. F., Borselli, M. & Petta, J. R. Coherent transfer of quantum information in a silicon double quantum dot using resonant swap gates. _npj Quantum Inf._ 5, 110 (2019).

Article ADS Google Scholar * Wang, X., Bishop, L. S., Kestner, J. P., Barnes, E. & Sun, K. Composite pulses for robust universal control of singlet-triplet qubits. _Nat. Commun._ 3,

997 (2012). Article ADS PubMed CAS Google Scholar * Zajac, D. M., Sigillito, A. J., Russ, M., Borjans, F. & Taylor, J. M. Resonantly driven CNOT gate for electron spins. _Science_

359, 439–442 (2018). Article ADS MathSciNet CAS PubMed MATH Google Scholar * Huang, W., Yang, C. H., Chan, K. W., Tanttu, T. & Hensen, B. Fidelity benchmarks for two-qubit gates

in silicon. _Nature_ 569, 532–536 (2019). Article ADS CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Watson, T. F., Philips, S. G. J., Kawakami, E., Ward, D. R. & Scarlino, P. A programmable two-qubit

quantum processor in silicon. _Nature_ 555, 633 (2018). Article ADS CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Yoneda, J., Takeda, K., Otsuka, T., Nakajima, T. & Delbecq, M. R. A quantum-dot spin

qubit with coherence limited by charge noise and fidelity higher than 99.9%. _Nat. Nanotechnol._ 13, 102–106 (2018). Article ADS CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Nielsen, M. A. &

Chuang, I. L. _Quantum Computation and Quantum Information: 10th Anniversary Edition_, 10th edn. (Cambridge University Press, New York, 2011). * Shulman, M. D., Harvey, S. P., Nichol, J. M.,

Bartlett, S. D. & Doherty, A. C. Suppressing qubit dephasing using real-time Hamiltonian estimation. _Nat. Commun._ 5, 5156 (2014). Article ADS CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Angus,

S. J., Ferguson, A. J., Dzurak, A. S. & Clark, R. G. Gate-defined quantum dots in intrinsic silicon. _Nano Lett._ 7, 2051–2055 (2007). Article ADS CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Zajac,

D. M., Hazard, T. M., Mi, X., Wang, K. & Petta, J. R. A reconfigurable gate architecture for Si/SiGe quantum dots. _Appl. Phys. Lett._ 106, 223507 (2015). Article ADS CAS Google

Scholar * Baart, T. A., Shafiei, M., Fujita, T., Reichl, C. & Wegscheider, W. Single-spin ccd. _Nat. Nanotechnol._ 11, 330 (2016). Article ADS CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Mills, A.

R., Zajac, D. M., Gullans, M. J., Schupp, F. J., Hazard, T. M. & Petta, J. R. Shuttling a single charge across a one-dimensional array of silicon quantum dots. _Nat. Commun._ 10, 1063

(2019). Article ADS CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Orona, L. A., Nichol, J. M., Harvey, S. P., Bøttcher, C. G. L. & Fallahi, S. Readout of singlet-triplet qubits at

large magnetic field gradients. _Phys. Rev. B_ 98, 125404 (2018). Article ADS CAS Google Scholar * Studenikin, S. A., Thorgrimson, J., Aers, G. C., Kam, A. & Zawadzki, P. Enhanced

charge detection of spin qubit readout via an intermediate state. _Appl. Phys. Lett._ 101, 233101 (2012). Article ADS CAS Google Scholar * Shulman, M. D., Dial, O. E., Harvey, S. P.,

Bluhm, H. & Umansky, V. Demonstration of entanglement of electrostatically coupled singlet-triplet qubits. _Science_ 336, 202–205 (2012). Article ADS CAS PubMed Google Scholar *

Dial, O. E., Shulman, M. D., Harvey, S. P., Bluhm, H. & Umansky, V. Charge noise spectroscopy using coherent exchange oscillations in a singlet-triplet qubit. _Phys. Rev. Lett._ 110,

146804 (2013). Article ADS CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Jones, A. M., Pritchett, E. J., Chen, E. H., Keating, T. E. & Andrews, R. W. Spin-blockade spectroscopy of Si/Si-Ge quantum

dots. _Phys. Rev. Appl._ 12, 014026 (2019). Article ADS CAS Google Scholar * Borselli, M. G., Ross, R. S., Kiselev, A. A., Croke, E. T. & Holabird, K. S. Measurement of valley

splitting in high-symmetry si/sige quantum dots. _Appl. Phys. Lett._ 98, 123118 (2011). Article ADS CAS Google Scholar * Higginbotham, A. P., Kuemmeth, F., Hanson, M. P., Gossard, A. C.

& Marcus, C. M. Coherent operations and screening in multielectron spin qubits. _Phys. Rev. Lett._ 112, 026801 (2014). Article ADS CAS PubMed Google Scholar * West, A., Hensen, B.,

Jouan, A., Tanttu, T. & Yang, C.-H. Gate-based single-shot readout of spins in silicon. _Nat. Nanotechnol._ 14, 437–441 (2019). Article ADS CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Zheng, G.,

Samkharadze, N., Noordam, M. L., Kalhor, N. & Brousse, D. Rapid gate-based spin read-out in silicon using an on-chip resonator. _Nat. Nanotechnol._ 14, 742–746 (2019). Article ADS CAS

PubMed Google Scholar * Elzerman, J. M., Hanson, R., Willems van Beveren, L. H., Witkamp, B., Vandersypen, L. M. K. & Kouwenhoven, L. P. Single-shot read-out of an individual

electron spin in a quantum dot. _Nature_ 430, 431–435 (2004). Article ADS CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Connors, E. J., Nelson, J. J. & Nichol, J. M. Rapid high-fidelity spin-state

readout in Si/Si − Ge quantum dots via rf reflectometry. _Phys. Rev. Appl._ 13, 024019 (2020). Article ADS CAS Google Scholar Download references ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS We thank Lieven

Vandersypen and Joseph Ciminelli for valuable discussions. This work was sponsored the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency under Grant No. D18AC00025; the Army Research Office under

Grant Nos. W911NF-16-1-0260, W911NF-19-1-0167, and W911NF-18-1-0178; and the National Science Foundation under Grant DMR-1809343. The views and conclusions contained in this document are

those of the authors and should not be interpreted as representing the official policies, either expressed or implied, of the Army Research Office or the U.S. Government. The U.S. Government

is authorized to reproduce and distribute reprints for Government purposes notwithstanding any copyright notation herein. AUTHOR INFORMATION Author notes * These authors contributed

equally: Haifeng Qiao, Yadav P. Kandel. AUTHORS AND AFFILIATIONS * Department of Physics and Astronomy, University of Rochester, Rochester, NY, 14627, USA Haifeng Qiao, Yadav P. Kandel,

Sreenath K. Manikandan, Andrew N. Jordan & John M. Nichol * Institute for Quantum Studies, Chapman University, Orange, CA, 92866, USA Andrew N. Jordan * Department of Physics and

Astronomy, Purdue University, West Lafayette, IN, 47907, USA Saeed Fallahi & Michael J. Manfra * Birck Nanotechnology Center, Purdue University, West Lafayette, IN, 47907, USA Saeed

Fallahi, Geoffrey C. Gardner & Michael J. Manfra * School of Materials Engineering, Purdue University, West Lafayette, IN, 47907, USA Geoffrey C. Gardner & Michael J. Manfra * School

of Electrical and Computer Engineering, Purdue University, West Lafayette, IN, 47907, USA Michael J. Manfra Authors * Haifeng Qiao View author publications You can also search for this

author inPubMed Google Scholar * Yadav P. Kandel View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Sreenath K. Manikandan View author publications You

can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Andrew N. Jordan View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Saeed Fallahi View author

publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Geoffrey C. Gardner View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Michael

J. Manfra View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * John M. Nichol View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google

Scholar CONTRIBUTIONS S.K.M., A.N.J., and J.M.N. conceptualized the experiment. Y.P.K., H.Q, and J.M.N. conducted the investigation. S.F., G.C.G., and M.J.M. provided resources and conducted

investigation. All authors participated in writing. J.M.N. supervised the effort. CORRESPONDING AUTHOR Correspondence to John M. Nichol. ETHICS DECLARATIONS COMPETING INTERESTS The authors

declare no competing interests. ADDITIONAL INFORMATION PEER REVIEW INFORMATION _Nature Communications_ thanks the anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this

work. PUBLISHER’S NOTE Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION SUPPLEMENTARY

INFORMATION RIGHTS AND PERMISSIONS OPEN ACCESS This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution

and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if

changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the

material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to

obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. Reprints and permissions ABOUT THIS ARTICLE CITE THIS

ARTICLE Qiao, H., Kandel, Y.P., Manikandan, S.K. _et al._ Conditional teleportation of quantum-dot spin states. _Nat Commun_ 11, 3022 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-16745-0

Download citation * Received: 28 April 2020 * Accepted: 21 May 2020 * Published: 15 June 2020 * DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-16745-0 SHARE THIS ARTICLE Anyone you share the

following link with will be able to read this content: Get shareable link Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article. Copy to clipboard Provided by the Springer

Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative