Risk factors of levodopa-induced dyskinesia in parkinson’s disease: results from the ppmi cohort

- Select a language for the TTS:

- UK English Female

- UK English Male

- US English Female

- US English Male

- Australian Female

- Australian Male

- Language selected: (auto detect) - EN

Play all audios:

ABSTRACT Levodopa-induced dyskinesias (LID) negatively impact on the quality of life of patients with Parkinson’s disease (PD). We assessed the risk factors for LID in a cohort of de-novo PD

patients enrolled in the Parkinson’s Progression Markers Initiative (PPMI). This retrospective cohort study included all PD patients enrolled in the PPMI cohort. Main outcome was the

incidence rate of dyskinesia, defined as the first time the patient reported a non-zero score in the item “Time spent with dyskinesia” of the MDS-UPDRS part IV. Predictive value for LID

development was assessed for clinical and demographical features, dopamine transporter imaging (DaTscan) pattern, cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) biomarkers (Aβ42, total tau, phosphorylated tau,

total α synuclein) and genetic risk score for PD. Overall, data from 423 PD patients were analyzed. The cumulative incidence rate of LID was 27.4% (95% CI = 23.2–32.0%), with a mean onset

time of 5.81 years from PD diagnosis. Multivariate Cox regression analysis showed several factors predicting LID development, including female gender (HR = 1.61, 95% CI = 1.05–2.47), being

not completely functional independent as measured by the modified Schwab & England ADL scale (HR = 1.81, 95% CI = 0.98–3.38), higher MDS-UPDRS part III score (HR = 1.03, 95% CI =

1.00–1.05), postural instability gait disturbances or intermediate phenotypes (HR = 1.95, 95% CI = 1.28–2.96), higher DaTscan caudate asymmetry index (HR = 1.02, 95% CI = 1.00–1.03), higher

polygenic genetic risk score (HR = 1.39, 95% CI = 1.08–1.78), and an anxiety trait (HR = 1.02, 95% CI = 1.00–1.04). In PD patients, cumulative levodopa exposure, female gender, severity of

motor and functional impairment, non-tremor dominant clinical phenotype, genetic risk score, anxiety, and marked caudate asymmetric pattern at DaTscan at baseline represent independent risk

factors for developing LID. SIMILAR CONTENT BEING VIEWED BY OTHERS PRODROMAL PARKINSON DISEASE SUBTYPES — KEY TO UNDERSTANDING HETEROGENEITY Article 20 April 2021 GENETIC META-ANALYSIS OF

LEVODOPA INDUCED DYSKINESIA IN PARKINSON’S DISEASE Article Open access 31 August 2023 LONGITUDINAL CLINICAL AND BIOMARKER CHARACTERISTICS OF NON-MANIFESTING _LRRK2_ G2019S CARRIERS IN THE

PPMI COHORT Article Open access 22 October 2022 INTRODUCTION Parkinson’s disease (PD) is a neurodegenerative disorder characterized by motor and non-motor symptoms.1 So far, levodopa still

stands as the most effective symptomatic treatment for PD.2 However, long-term dopamine repletion treatment may lead to motor fluctuations, such as wearing-off and dyskinesias.3,4 Several

factors participate in the development of motor fluctuations, including loss of dopaminergic neurons in the substantia nigra, changes in pre and post-synaptic striatal activity with chronic

pulsatile stimulation of dopamine receptors,5 and the daily dosage of levodopa.6 Motor fluctuations highly impact on the quality of life of people with PD, representing a major criteria for

eligibility to advanced treatments.6 Observational studies have shown that more than 50% of PD patients treated with levodopa for more than 5 years develop levodopa-induced dyskinesia

(LID).7 Several risk factors for LID have been proposed, including levodopa dosage,8 treatment duration,9 female gender10 and low body weight.11 Other factors have been investigated as

predisposing to LID, including neuroimaging findings, with conflicting results.12,13,14,15 It is worth noticing that the available studies are poorly comparable, given the different

methodological approaches and follow-up duration, with patients being rarely followed up ever since de novo stage. The Parkinson’s Progression Markers Initiative (PPMI) is a large-scale

international prospective observational study, started in 2010, designed to identify markers of disease progression in de novo PD patients. Clinical, neuroimaging and CSF/blood biomarkers

are collected yearly. We wanted to define factors predictive of LID development already in de novo stage of PD. RESULTS COHORT CHARACTERISTICS AND LID INCIDENCE Baseline demographic and

disease characteristics of the cohort divided by the LID− (patients without LID) versus LID+ (patients developing LID) subgroups are presented in Table 1. At the time of data analysis, the

median duration of follow-up was 4.6 years (min 0.0/max 6.4). Overall, 109/390 subjects experienced LID (27.9%, 95% CI 23.7% to 32.6%). In 33/109 patients experiencing LID, data regarding

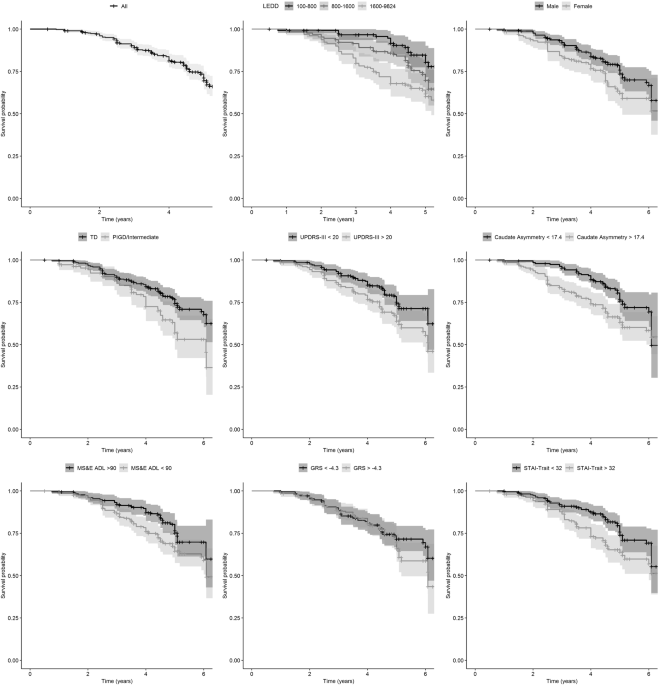

levodopa treatment and/or LID onset were missing. The median time to LID (Fig. 1) was 3.6 years (min 0.8/max 7.1) with an incidence rate of 64 per 1000 person-years. ANALYSIS OF MULTIPLE

RISK FACTORS FOR TIME TO INITIATION OF DOPAMINERGIC THERAPY The average time for initiating a dopaminergic therapy was 1 year. Multivariate Cox regression analysis has shown that a

combination of several factors was mildly accurate in predicting the initiation of dopaminergic therapy (Concordance = 0.61, 95% CI 0.57 to 0.64). The Cox proportionality assumption was

validated with chi-square test for Schoenfeld residuals (overall _p_-value = 0.089); visual inspection of martingale residuals against individual covariates supported the linearity

hypothesis. The final model included disease duration (HR = 0.81, 95% CI 0.66 to 1.00), Modified Schwab & England ADL score <90 (HR = 1.58, 95% CI 1.09 to 2.32), higher MDS-UPDRS part

III (HR = 1.02, 95% CI 1.01 to 1.03), contralateral putamen (HR = 0.47, 95% CI 0.30 to 0.73), the polygenic risk score (HR = 1.18, 95% CI 1.04 to 1.34), and the anxiety trait as measured by

STAI subscore (HR = 1.01, 95% CI 1.00 to 1.03). ANALYSIS OF RISK FACTORS FOR LID The mean time for onset of dyskinesia after the initiation of any dopaminergic therapy was 3.6 years. The

predictive value of each variable for investigating the incidence of LID was explored using Cox regression models, with total Levodopa equivalent daily dose (LEDD) included as covariate.

Female gender was associated to a greater risk of developing dyskinesia (HR = 1.79, 95% CI 1.21 to 2.66, Table 2, Fig. 1). Several clinical characteristics were associated with incidence of

dyskinesia such as Modified Schwab & England ADL (HR = 0.96, 95% CI 0.93 to 0.99, Table 2, Fig. 1), PIGD/Intermediate phenotype (HR = 1.75, 95% CI 1.18 to 2.59, Table 2, Fig. 1),

MDS-UPDRS part III (HR = 1.03, 95% CI 1.01 to 1.05, Table 2, Fig. 1), and PIGD subtype (HR = 3.11, 95% CI 1.42 to 6.79, Table 2, Fig. 1). Interestingly, several DaTscan measures were

associated with a greater risk of dyskinesia such as contralateral putamen (HR = 0.40, 95% CI 0.14 to 0.84, Table 2, Fig. 1), caudate asymmetry index (HR = 1.02, 95% CI 1.01 to 1.04, Table

2, Fig. 1), and putamen asymmetry index (HR = 1.01, 95% CI 1.00 to 1.02, Table 2, Fig. 1). In addition, onset of dyskinesia was associated with psychiatric features such as depression (HR =

1.11, 95% CI 1.04 to 1.19, Table 2) and anxiety as measured by STAI-State score (HR = 1.02, 95% CI 1.00 to 1.04, Table 2) and STAI-Trait score (HR = 1.04, 95% CI 1.02 to 1.06, Table 2, Fig.

1). None of the CSF biomarkers showed any predictive power. ANALYSIS OF MULTIPLE RISK FACTORS FOR LID Multivariate Cox regression analysis has shown that a combination of multiple factors

was fairly accurate in predicting the onset of dyskinesia (Concordance = 0.74, 95% CI 0.681 to 0.80). The Cox proportionality assumption was validated with chi-square test for Schoenfeld

residuals (overall _p_-value = 0.383), and visual inspection of martingale residuals against individual covariates supports the hypothesis of linearity. The final model included female

gender (HR = 1.63, 95% CI 1.06 to 2.50, Table 3), 1000 mg/d of Levodopa LEDD (HR = 1.22, 95% CI 1.08 to 1.38, Table 3), STAI Trait score (HR = 1.03, 95% CI 1.00 to 1.05, Table 3), Modified

Schwab & England ADL (HR = 0.97, 95% CI 0.93 to 1.01, Table 3), MDS-UPDRS part III (HR = 1.03, 95% CI 1.00 to 1.05, Table 3), PIGD/Intermediate phenotype (HR = 2.04, 95% CI 1.33 to 3.13,

Table 3), caudate asymmetry index (HR = 1.02, 95% CI 1.00 to 1.03, Table 3), and the genetic risk score (HR = 1.35, 95% CI 1.05 to 1.74, Table 3). RANDOM SURVIVAL FORESTS FOR LID After

fitting random survival forests with 1000 trees and missing data imputation, 12 variables were selected using minimal depth criterion leading to an out-of-bag error of 24%. The final model

was consistent with the results of multivariate Cox regression in terms of the selected variables. Using random survival forests, also CSF biomarkers entered in the panel of predictive

factors (Table 2) for LID development, with α-syn ranking 6th according to the importance of all variables (Fig. 2). DISCUSSION LID negatively affects the quality of life of patients with

PD. Despite extensive research, conflicting results have been gathered regarding modifiable and non-modifiable risk factors for LID development,16 with few studies assessing de novo

patients. In this study, evaluating data of de novo PD patients included in the PPMI cohort, we identified a set of seven independent risk factors for LID development that can be taken into

consideration already in the very early phase of the disease. First of all, we confirm that female gender represents a crucial non-modifiable predictive factor for LID,10 independently from

body weight and genetic factors.10,11,17 Second, our results underline that cumulative exposure to levodopa is positively associated with the development of LID, in line with the results

deriving from other large cohorts of PD patients.18,19 Noteworthy, it is well known that levodopa accelerates the loss of nigrostriatal dopamine nerve terminals, a key pathophysiologic

element in the development of dyskinesia. Dyskinesia in Parkinson’s disease are associated with changes in long term neuroadaptation and neuronal synaptic plasticity which in turn are linked

to dopamine transporters and receptors density, respectively at a presynaptic and a postsynaptic level.6 Based on this concept, both positron emission tomography (PET) and single photon

emission computed tomography (SPECT) were used to assess changes in neurotransmitter pathways involved in dyskinesia and, subsequently, to identify imaging biomarkers for LID development.

Notably, lower dopamine transporter activity in the putamen evaluated by 18F-FP-CIT-PET in de-novo PD patients has been described as significant predictor of LID.13 Our results indicate that

dopamine deficits in the contralateral putamen in de-novo PD patients is an independent predictor of a shorter time to levodopa initiation. Besides, both putamen asymmetry and caudate

asymmetry indices evaluated by [123I]FP-CIT-SPECT significantly correlated with the development of dyskinesia, with the caudate asymmetry entering in the multivariate model. These findings

reflect previous evidences indicating a positive relationship between the striatal asymmetric index and the magnitude of response to levodopa.20 Thus, PD patients with higher striatal

asymmetric index show an increase of both response to levodopa and susceptibility to dyskinesia. The probability of developing dyskinesia in Parkinson’s disease is also influenced by the

initial clinical phenotype. Our findings showed that tremor-dominant (TD) phenotype is at lower risk of LID compared to PIGD or Intermediate. Previous studies have already demonstrated that

tremor-dominant manifestation at disease onset is associated with a reduced risk of LID compared to rigid-akinetic (RA) phenotype.21 The reason of a lower risk of dyskinesia among TD

patients may lay in different patterns of nigrostriatal denervation, morphologic lesions of the basal ganglia subregions and pathophysiological mechanisms between different phenotypes.5

Furthermore, TD patients usually show lower striatal dopamine depletion compared to RA patients on [123I]FP-CIT-SPECT,22 suggesting a less pronounced predisposition to LID. Nigrostriatal

dopamine depletion is one of the main prerequisite for developing dyskinesia and dopaminergic denervation is increased by disease severity. Therefore, it is not surprising that disease

severity at baseline represents an important predictive factor for LID. Our findings indicate that UPDRS Part III score in de-novo patients is a significant clinical biomarker to predict

dyskinesia. However, it is not fully consistent with data from STRIDE-PD trial which showed UPDRS Part II score as risk factor for dyskinesia, whereas UPDRS Part III did not correlate with

dyskinesia development.19 Such contrasting results may be due to the fact that UPDRS motor score does not always reflect precisely the status of presynaptic dopamine denervation evaluated by

PET or SPECT.23 The relationship between the severity of disease and the susceptibility to dyskinesia is also supported by the significant inverse correlation we found between ADL Scale

score and risk of LID. Thus, patients with higher disease severity testified by greater impairment on daily living activities are more prone to develop dyskinesia. Genetic susceptibility to

dyskinesia is of great interest, with conflicting results deriving from several studies focusing on single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) of different genes. PPMI polygenic risk score was

developed to explain the risk of idiopathic PD onset so far and it does not include several genes that are known to increase the risk of developing LID.24 However, to the best of our

knowledge, for the first time in this study we highlighted a correlation between cumulative effect of known genetic risk variants of PD and LID development. Such results, if corroborated by

extensive genome-wide association studies (GWAS), might represent a focus for future research. Interestingly, we also found that anxiety was associated to an increased risk of dyskinesia.

This could be linked to the relationship between dopaminergic dysfunction and neuropsychiatric symptoms in early PD.25 Although CSF biomarkers did not explain LID onset in the Cox

regression, we found that α-syn ranked 6th, according to the variable importance criterion, in the random survival forests model. This suggest that further investigations are warranted for

exploring the role of CSF α-syn in predicting LID, with special attention to pay for the observation in larger cohorts or the measurement of oligomeric and phosphorylated forms. There are

limitations in our data, mainly due to the evaluation of dyskinesia. Even if specific scales have been validated to assess dyskinesia in PD,26 they were not used for evaluating qualitative

and quantitative aspects of dyskinesia in the PPMI. Therefore, our results neither identified predictive factors for different types of dyskinetic complication in PD (chorea versus dystonia)

nor found a possible explanation for the severity of dyskinesia. In summary, our findings indicate that data deriving from a large cohort of de-novo PD patients monitored longitudinally are

useful in understanding the composite aspects involved in the progression of disease. Our results highlight the role of several factors in determining dyskinesia, thus providing useful

information for future design of both biomarker studies and randomized clinical trials. METHODS STUDY DESIGN Overall, 423 de novo PD participants were enrolled in the PPMI study between

January 2011 and December 2012. Data were obtained from the PPMI database accessed 30 December 2017. PARTICIPANTS The inclusion criteria for entering PPMI were: (i) age >30; (ii) presence

of at least two parkinsonian signs such as bradykinesia, rigidity and resting tremor or have an asymmetric resting tremor, or asymmetric bradykinesia; (iii) having received the diagnosis

not earlier than two years before enrollment; (iv) documented reduced striatal 123-I Ioflupane dopamine transporter (DatScan, GE Healthcare, Arlington Heights, IL) imaging binding consistent

with PD; (v) no ongoing symptomatic therapy. Each PPMI participant received extensive assessment of motor and non-motor features. STANDARD PROTOCOL APPROVALS, REGISTRATIONS, AND CONSENTS

Each participating PPMI site received approval from an ethical standards committee on human experimentation before study initiation. Written informed consent for research was obtained from

all individuals participating in the study. BASELINE FEATURES With the aim of defining predictive factors od LID development among _de novo_ patients, we have investigated several variables

available at baseline, including: (i) demographics (age, gender, family history, disease duration, education years); (ii) bradykinesia, rigidity and tremor were assessed according to UK

Parkinson’s Disease Society Brain Bank Criteria (iii) motor features (International Parkinson’s disease and Movement Disorder Society-Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale

(MDS-UPDRS)-Part II and III, total tremor score, postural instability–gait disturbance (PIGD) score, tremor/PIGD motor phenotype, Schwab-England activities of daily living (ADL) score,

bradykinesia, tremor, and (iv) age/education adjusted Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA); (v) non-motor manifestations (MDS-UPDRS-Part I), olfactory dysfunction via University of

Pennsylvania Smell Identification Test (UPSIT) score, autonomic dysfunction via Scale for Outcomes in Parkinson’s disease-Autonomic (SCOPA-AUT) total score, REM sleep behaviour disorder

(RBD) via RBD screening questionnaire (RBDSQ) score, sleep disturbances via Epworth Sleepiness Score (ESS), anxiety via State‐Trait Anxiety Inventory scores (STAI), depression via Geriatric

Depression Scale (GDS-15); (vi) genetic risk score including 28 independent risk variants for PD that have been selected according to the results of a meta-analysis of PD genome-wide

association studies,24 also including p.N370S in GBA and p.G2019S in LRRK227,28; (vii) CSF biomarkers (CSF amyloid-β1-42, total (t)-tau, and phosphorylated tau (P-tau181) and a-synuclein);

(viii) dopamine transporter imaging striatal-binding ratios (DATscan) (single-photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) with the DAT tracer 123I-ioflupane at baseline, with

striatal-binding ratio calculated for left and right putamen separately using the occipital lobe as reference, obtaining ipsilateral, contralateral, mean measurements and asymmetry indices).

The asymmetry index for caudate and putamen was calculated, according to PPMI indications for deriving variables, as the difference between left and right divided by the mean value.

LEVODOPA EXPOSURE Levodopa equivalent daily dose (LEDD) was reported for each participant reporting the initiation of dopaminergic therapy. We included total LEDD as the cumulative exposure

to all dopaminergic drugs, as well as levodopa LEDD as the cumulative exposure to levodopa until the onset of dyskinesia (observed events) or the study exit (censored events).

LEVODOPA-INDUCED DYSKINESIA The primary outcome was the incidence of LID, defined as the first time the patient reported a positive score in the item “Time spent with dyskinesia” of the

MDS-UPDRS part IV. STATISTICAL ANALYSIS Statistical analyses were performed using R software version 3.4. Continuous variables were described by means and standard deviations, while

categorical ones were reported as count and percentages. Predictors of LID onset were assessed using multivariate Cox proportional hazards regression models. In the absence of a conversion

event, data were censored at the most recent clinic visit. We have first assessed the role of each risk factor in conjunction with the total LEDD. In order to avoid rejection of potentially

important variables due to uncontrolled confounders, a p-value lower than 0.20 was used as screening criterion to consider the risk factor as candidate for the multivariate analysis.

Backward elimination based on the Akaike’s information criterion was used to select a final model. Hazard proportionality was assessed through analysis of scaled Schoenfeld residuals whereas

martingale residuals were plotted against continuous covariates to detect nonlinearity. As a complementary approach, we have applied random survival forests,29 a machine learning technique

to determine important variables for the prediction of individual survival times. Variable selection was carried out using a conservative approach based on minimal depth criterion.

Significance level of 5% was assumed for all the analyses. DATA AVAILABILITY Data used in the preparation of this study were obtained from the PPMI database (www.ppmi-info.org/data). For

up-to-date information on the study, visit http://www.ppmi-info.org. REFERENCES * Fereshtehnejad, S. M., Zeighami, Y., Dagher, A. & Postuma, R. B. Clinical criteria for subtyping

Parkinson’s disease: biomarkers and longitudinal progression. _Brain_ 140, 1959–1976 (2017). Article Google Scholar * Tambasco, N., Romoli, M. & Calabresi, P. Levodopa in Parkinson’s

disease: current status and future developments. _Curr. Neuropharmacol._ 15, 1–13 (2017). Google Scholar * Fahn, S. et al. Levodopa and the progression of Parkinson’s disease. _N. Engl. J.

Med._ 351, 2498–508 (2004). Article CAS Google Scholar * Abbott, A. Levodopa: the story so far. _Nature_ 466, S6–S7 (2010). Article CAS Google Scholar * Calabresi, P. et al.

Levodopa-induced dyskinesias in patients with Parkinson’s disease: filling the bench-to-bedside gap. _Lancet Neurol._ 9, 1106–1117 (2010). Article CAS Google Scholar * Picconi, B.,

Hernández, L. F., Obeso, J. A. & Calabresi, P. Motor complications in Parkinson’s disease: striatal molecular and electrophysiological mechanisms of dyskinesias. _Mov. Disord._ 33,

867–876 (2018). Article Google Scholar * Grandas, F., Galiano, M. L. & Tabernero, C. Risk factors for levodopa-induced dyskinesias in Parkinson’s disease. _J. Neurol._ 246, 1127–1133

(1999). Article CAS Google Scholar * Fahn, S. Levodopa in the treatment of Parkinson’ s disease. _J. Neural Transm._ 71, 1–15 (2006). CAS Google Scholar * Schrag, A. & Quinn, N.

Dyskinesias and motor fluctuations in Parkinson’s disease. _Brain_ 123, 2297–2305 (2000). Article Google Scholar * Zappia, M. et al. Sex differences in clinical and genetic determinants of

levodopa peak-dose dyskinesias in Parkinson disease. _Arch. Neurol._ 62, 601 (2005). Article Google Scholar * Arabia, G. et al. Body weight, levodopa pharmacokinetics and dyskinesia in

Parkinson’s disease. _Neurol. Sci._ 23, 53–54 (2002). Article Google Scholar * Yoo, H. S. et al. Presynaptic dopamine depletion determines the timing of levodopa-induced dyskinesia onset

in Parkinson’s disease. _Eur. J. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imaging_ 1–9 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00259-017-3844-8 Article Google Scholar * Hong, J. Y. et al. Presynaptic dopamine depletion

predicts levodopa-induced dyskinesia in de novo Parkinson disease. _Neurology_ 82, 1597–1604 (2014). Article CAS Google Scholar * Linazasoro, G. et al. Levodopa-induced dyskinesias in

parkinson disease are independent of the extent of striatal dopaminergic denervation: a pharmacological and SPECT study. _Clin. Neuropharmacol._ 32, 326–329 (2009). Article CAS Google

Scholar * De La Fuente-Fernndez, R. et al. Biochemical variations in the synaptic level of dopamine precede motor fluctuations in Parkinson’s disease: PET evidence of increased dopamine

turnover. _Ann. Neurol._ 49, 298–303 (2001). Article Google Scholar * Sharma, J. C., Bachmann, C. G. & Linazasoro, G. Classifying risk factors for dyskinesia in Parkinson’s disease.

_Park. Relat. Disord._ 16, 490–497 (2010). Article CAS Google Scholar * Blanchet, P. J. et al. Short-term effects of high-dose 17beta-estradiol in postmenopausal PD patients: a crossover

study. _Neurology_ 53, 91–95 (1999). Article CAS Google Scholar * Penney, J. B. et al. Impact of deprenyl and tocopherol treatment on Parkinson’s disease in DATATOP patients requiring

levodopa. _Ann. Neurol._ 39, 37–45 (1996). Article CAS Google Scholar * Warren Olanow, C. et al. Factors predictive of the development of Levodopa-induced dyskinesia and wearing-off in

Parkinson’s disease. _Mov. Disord._ 28, 1064–1071 (2013). Article CAS Google Scholar * Contrafatto, D. et al. Single photon emission computed tomography striatal asymmetry index may

predict dopaminergic responsiveness in Parkinson disease. _Clin. Neuropharmacol._ 34, 71–3 (2011). CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Kipfer, S., Stephan, M. A., Schüpbach, W. M. M., Ballinari,

P. & Kaelin-Lang, A. Resting tremor in Parkinson disease: a negative predictor of levodopa-induced dyskinesia. _Arch. Neurol._ 68, 1037–1039 (2011). Article Google Scholar * Rossi, C.

et al. Differences in nigro-striatal impairment in clinical variants of early Parkinson’s disease: evidence from a FP-CIT SPECT study. _Eur. J. Neurol._ 17, 626–630 (2010). Article CAS

Google Scholar * Benamer, H. T. S. et al. Correlation of Parkinson’s disease severity and duration with 123I-FP-CIT SPECT striatal uptake. _Mov. Disord._ 15, 692–698 (2000). Article CAS

Google Scholar * Nalls, M. A. et al. Large-scale meta-analysis of genome-wide association data identifies six new risk loci for Parkinson’s disease. _Nat. Genet._ 46, 989–993 (2014).

Article CAS Google Scholar * Picillo, M. et al. Association between dopaminergic dysfunction and anxiety in de novo Parkinson’s disease. _Park. Relat. Disord._ 37, 106–110 (2017). Article

Google Scholar * Colosimo, C. et al. Task force report on scales to assess dyskinesia in Parkinson’s disease: critique and recommendations. _Mov. Disord._ 25, 1131–1142 (2010). Article

Google Scholar * International Parkinson Disease Genomics Consortium et al. Imputation of sequence variants for identification of genetic risks for Parkinson’s disease: a meta-analysis of

genome-wide association studies. _Lancet_ 377, 641–9 (2011). Article Google Scholar * Nalls, M. A. et al. Baseline genetic associations in the Parkinson’s Progression Markers Initiative

(PPMI). _Mov. Disord._ 31, 79–85 (2016). Article CAS Google Scholar * Ishwaran, H., Kogalur, U. B., Blackstone, E. H. & Lauer, M. S. Random survival forests. _Ann. Appl. Stat._ 2,

841–860 (2008). Article Google Scholar Download references ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This study was supported by the Italian Ministry of Health (Grant GR-2013‐02357757). The Movement Disorders

Center of the University of Perugia was supported by a grant from New York University School of Medicine and The Marlene and Paolo Fresco Institute for Parkinson’s and Movement Disorders,

which was made possible with support from Marlene and Paolo Fresco. AUTHOR INFORMATION Author notes * These authors contributed equally: Paolo Eusebi, Michele Romoli. AUTHORS AND

AFFILIATIONS * Neurology Clinic, Department of Medicine, University of Perugia, Ospedale S. Maria della Misericordia, Perugia, Italy Paolo Eusebi, Michele Romoli, Federico Paolini Paoletti,

Nicola Tambasco, Paolo Calabresi & Lucilla Parnetti * IRCCS Santa Lucia, Rome, Italy Paolo Calabresi Authors * Paolo Eusebi View author publications You can also search for this author

inPubMed Google Scholar * Michele Romoli View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Federico Paolini Paoletti View author publications You can

also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Nicola Tambasco View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Paolo Calabresi View author

publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Lucilla Parnetti View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar CONTRIBUTIONS

P.E., M.R., F.P., P.C., and L.P. conceived the idea, planned and designed the study. P.E., M.R., and F.P. wrote the first draft; P.E. planned the data management and statistical analysis;

N.T. provided critical insights. P.E., M.R., F.P., N.T., P.C., and L.P. have approved and contributed to the final written manuscript. CORRESPONDING AUTHOR Correspondence to Lucilla

Parnetti. ETHICS DECLARATIONS COMPETING INTERESTS The Authors declare no competing interests. ADDITIONAL INFORMATION PUBLISHER’S NOTE: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to

jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. RIGHTS AND PERMISSIONS OPEN ACCESS This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International

License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source,

provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons

license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by

statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. Reprints and permissions ABOUT THIS ARTICLE CITE THIS ARTICLE Eusebi, P., Romoli, M., Paoletti, F.P. _et al._ Risk factors of levodopa-induced

dyskinesia in Parkinson’s disease: results from the PPMI cohort. _npj Parkinson's Disease_ 4, 33 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41531-018-0069-x Download citation * Received: 26 June

2018 * Accepted: 24 October 2018 * Published: 16 November 2018 * DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41531-018-0069-x SHARE THIS ARTICLE Anyone you share the following link with will be able to

read this content: Get shareable link Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article. Copy to clipboard Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing

initiative