Prevalence and possible factors of myopia in norwegian adolescents

- Select a language for the TTS:

- UK English Female

- UK English Male

- US English Female

- US English Male

- Australian Female

- Australian Male

- Language selected: (auto detect) - EN

Play all audios:

ABSTRACT East Asia has experienced an excessive increase in myopia in the past decades with more than 80% of the younger generation now affected. Environmental and genetic factors are both

assumed to contribute in the development of refractive errors, but the etiology is unknown. The environmental factor argued to be of greatest importance in preventing myopia is high levels

of daylight exposure. If true, myopia prevalence would be higher in adolescents living in high latitude countries with fewer daylight hours in the autumn-winter. We examined the prevalence

of refractive errors in a representative sample of 16–19-year-old Norwegian Caucasians (n = 393, 41.2% males) in a representative region of Norway (60° latitude North). At this latitude,

autumn-winter is 50 days longer than summer. Using gold-standard methods of cycloplegic autorefraction and ocular biometry, the overall prevalence of myopia [spherical equivalent refraction

(SER) ≤−0.50 D] was 13%, considerably lower than in East Asians. Hyperopia (SER ≥ + 0.50 D), astigmatism (≥1.00 DC) and anisometropia (≥1.00 D) were found in 57%, 9% and 4%. Norwegian

adolescents seem to defy the world-wide trend of increasing myopia. This suggests that there is a need to explore why daylight exposure during a relatively short summer outweighs that of the

longer autumn-winter. SIMILAR CONTENT BEING VIEWED BY OTHERS PREVALENCE AND ASSOCIATED FACTORS OF MYOPIA AMONG ADOLESCENTS AGED 12–15 IN SHANDONG PROVINCE, CHINA: A CROSS-SECTIONAL STUDY

Article Open access 27 July 2024 MYOPIA PREVALENCE AND OCULAR BIOMETRY: A CROSS-SECTIONAL STUDY AMONG MINORITY VERSUS HAN SCHOOLCHILDREN IN XINJIANG UYGUR AUTONOMOUS REGION, CHINA Article

Open access 19 August 2021 PREVALENCE OF MYOPIA AND ITS RISK FACTORS IN RURAL SCHOOL CHILDREN IN NORTH INDIA: THE NORTH INDIA MYOPIA RURAL STUDY (NIM-R STUDY) Article 13 October 2021

INTRODUCTION East and Southeast Asia have experienced an excessive increase in myopia in the past few decades, with more than 80% of the younger generation now affected1,2. Myopia is a major

health concern3,4,5, as myopia, and in particular high myopia, may lead to potentially sight-threatening secondary ocular pathology6. The “epidemic” scale of myopia is most commonly

observed in highly economically developed countries, where children complete secondary education and many undertake upper- and post-secondary studies, combined with limited time spent

outdoors7,8. Environmental and genetic factors are both assumed to contribute in the development of refractive errors9,10, although there is no general agreement on the etiology of myopia.

The environmental factor argued to be of greatest importance in preventing myopia is time spent outdoors prior to myopia _onset_11,12,13 (it is debated whether time outdoors has an effect on

myopia _progression_14,15,16,17,18,19). A dose-response relationship between daylight (outdoor) exposure and ocular axial elongation (associated with developing myopia) has been inferred17.

Reported seasonal variation in axial length growth and myopia progression (with decreased eye growth and decreased myopia progression in periods with increased number of daylight

hours20,21) is often cited in support of the protective effect of outdoors. Such an explanation warrants further examination and calls for refractive error data from different parts of the

world3,22, in particular countries with high performing education systems and differing levels of seasonal variation in daylight. Norway’s northern latitude stretches from 58° to 71° North,

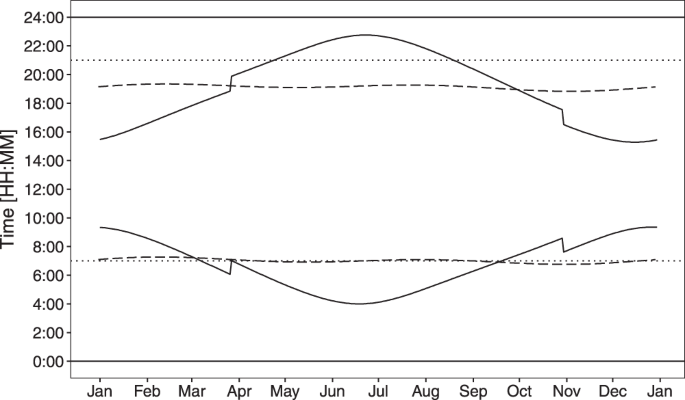

with even those living in Southeast Norway (60° North) experiencing large seasonal variation in daylight exposure, from less than 6 hours in December to around 19 hours in June (Fig. 1)23.

Norway is a highly economically developed country, ranked as number 1 in the Human Development report 2016, with high gender equality24. Norwegian children start primary school at age 6

years and complete 10 years of compulsory schooling before reaching upper secondary school, at age 16 years. Most of today’s adolescents will also have attended kindergartens from age 1–5

years (76.2% in 2005)25. The Norwegian education system is high-performing, as classified by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) Programme for International

Student Assessment (PISA), with both mean performance and the proportion of top performers above the OECD average in science, reading and mathematics26. Near work includes high usage of near

electronic devices (NED) at school and at home, with the use of NED reported to be above the OECD average27. If high levels of daylight exposure are necessary to protect against myopia, it

is reasonable to hypothesize that myopia onset will occur earlier, progression will be faster, and prevalence will be higher in adolescents living in countries with relatively few daylight

hours across an extended (5–6 months of autumn-winter) period28, particularly so, if combined with a high level of near work29,30. The current study tested this hypothesis. Its aim,

therefore, was to examine the prevalence of refractive errors in adolescents in Southeast Norway and assess the relationship between refractive errors, ocular biometry, sex and environmental

factors such as self-reported time spent on activities outdoors and indoors. METHODS STUDY POPULATION AND RECRUITMENT A cross-sectional study was carried out on students from the only two

upper secondary schools within a catchment area comprising five municipalities in Southeast Norway during 2015–2016. The catchment area is representative of the Norway population in terms of

socio-demographic status (details are given in Supplementary Tables S1–S4), with 70.7% living in urban settlements and an average population densities of 4–36 persons/km2 31. The total

population of the region was 49,293 in 2016, with 1,737 of these aged 16–19 years32,33. The total student population of the two schools was 1,970 (age 16–24 years), 676 and 1,294 in the

first and second schools respectively. The students attend school 5 days a week for 5–8 hours per day, with the school day beginning no earlier than 8 am; in addition, students undertake

homework in the evenings and on weekends. By agreement with school administrators, we were given access to 898 students (45.6%) who were all invited to participate; all students in all three

years in the first school and those in their first year (typical age 16–17 years) in the second school. The sample was representative of the school’s catchment area with respect to

ethnicity and grade point averages (see Supplementary Tables S2 and S5). The study was carried out at the schools during normal school hours. Verbal and written information about the study

was given, and possible consequences of the study were explained to all participants before written informed consent was obtained. The research was approved by the Regional Committee for

Medical Research Ethics for the Southern Norway Regional Health Authority and carried out in accordance with the principles embodied in the Declaration of Helsinki. A person aged 16 years or

older is considered an adult and fully competent to consent to participate in research according to the Norwegian Health Research Act. PARTICIPANTS Of those invited, a sample of 439 (48.9%)

students aged 16–19 years [mean age (_SD_): 16.7 (±0.9) years, 41.9% males] agreed to participate in the study. Self-reported ethnicity was mainly European Caucasians (90.9%); other

ethnicities were Asian (5.5%), African (1.4%), South American (0.9%), or mixed (defined as having parents of two different ethnicities, 1.4%). Analysis beyond calculation of prevalence of

hyperopia and myopia was limited to the participants who reported to have both grown up in Norway and who were of Northern European (Caucasian) ethnicity [n = 393, mean age 16.7 (±0.9)

years, 41.2% males], hereafter termed Norwegians. This group included participants born in Norway (98.7%) and five participants born in a different Northern European country (1.3%; born in

Denmark, Iceland, Germany and Holland), all of whom reported to have moved to Norway during their childhood. Removal of these five participants from the group had no overall effect on the

results. The Norwegian participants were grouped according to sex and age for the purpose of analysis (16-years-olds: n = 224, 42.4% males; 17–19-years-olds: n = 169, 39.6% males).

CYCLOPLEGIC AUTOREFRACTION AND OTHER MEASUREMENTS Cycloplegic autorefractions were obtained with a Huvitz HRK-8000A Auto-REF Keratometer (Huvitz Co. Ltd., Gyeonggi-do, Korea), 15–20 minutes

after instillation of topical 1% cyclopentolate hydrochloride (Minims single dose; Bausch & Lomb UK Ltd, England). One drop of cyclopentolate was used for blue- and green-eyed

participants, and two drops for brown-eyed participants. The mean of five measurements automatically performed by the instrument (Huvitz HRK-8000A) were used for further analyses. One

qualified optometrist (author JVBG) performed all autorefraction and biometry measurements. Ocular axial lengths (AL) and corneal radii (CR) were measured with Zeiss IOLMaster (Carl Zeiss

Meditec AG, Jena, Germany). Body height was measured with the Seca 217 stable stadiometer for mobile height measurement (Seca Deutschland, Hamburg, Germany). QUESTIONNAIRE Participants

completed an online questionnaire, an adapted version of the one used in the Sydney Myopia study34, to obtain demographic data and to quantify the amount of time spent on various indoor and

outdoor activities. Demographic data included place of birth, number of years lived in Southeast Norway, house type and distance to school. Information about access to, and use of, near

electronic devices (NED; smart phones, tablets, computers) was also collected. The reported mean hours per day spent on outdoor- and indoor- activities were calculated for those participants

who completed all questions related to time spent on various activities [68.4%, n = 269, 40.1% males, mean age 16.7 (±0.9) years]. Indoor activities included mean time spent on reading and

writing on paper (books, newspapers, magazines), use of NED, indoor sport (gymnastics, dance, ball games, etc) and other indoor activities (watching television, playing video games, hobbies,

cooking, etc). Outdoor activities included mean time spent on outdoor sport (cycling, skiing, running, etc) and other outdoor activities (walking to school, hiking, fishing, hunting,

spending time in the garden etc). The participants were asked to estimate the daily time usually spent on these activities for both weekdays and weekends and about what they do in the

school’s recess time. They were given four categorical response options for the estimate of activity hours per day; “Not at all”, “Less than 1 hour”, “1–2 hours”, or “3 hours or more”. The

mean numbers of activity hours per day were calculated using “0 hour”, “1 hour”, “2 hours” or “3 hours” for each option, respectively, as follows:

$$Mean\,hours\,per\,day=\,\frac{(hours\,spent\,on\,weekdays\times 5)+(hours\,spent\,on\,weekends\times 2)}{7}$$ (1) Finally, the participants were asked to estimate the ratio of indoor to

outdoor activities during their school holidays. Data were collected during February and March at both schools. ANALYSIS Spherical equivalent refractive errors (SER = sphere + ½ cylinder),

specified in terms of a 13.5 mm vertex distance, were used to classify refractive errors. Myopia was defined as SER ≤ −0.50 D, emmetropia as −0.50 D < SER < + 0.50 D, and hyperopia as

SER ≥ + 0.50 D. The most positive meridian of the autorefractor measurement was defined as the sphere, and the prevalence of refractive astigmatism is reported as negative cylinder

refraction ≥1.00 DC. SER, sphere and refractive astigmatism were all well correlated between the right and left eyes (SER: Spearman rho (_ρ_) = 0.94; sphere: _ρ_ = 0.92; refractive

astigmatism: _ρ_ = 0.59; all _p_ < 0.001), and thus only data from the right eye are presented. A SER-difference ≥1.00 D between right and left eye was defined as anisometropia. CR data

represent the mean of the corneal radii measured in the flattest and steepest meridians. AL/CR-ratios were also calculated. The Clopper-Pearson interval method and the method of Sison and

Glaz were used for calculation of 95% binomial and multinomial proportion confidence intervals (CI), respectively. QQ-plots, histograms and the Shapiro-Wilk test were used to assess the

normality of the variables. Means (±_SD_) are reported, in addition to the median (50th percentile) for non-normal data. The chi-square test, Fisher’s exact test, and independent sample

_t_-test were used to assess differences in prevalence and mean values between groups. Maximum likelihood estimate was used to fit a suitable distribution to the data for SER35. Linear

regression analyses were performed with SER, AL, AL/CR-ratio and cylinder as the dependent outcome variables. Multivariate logistic regression analyses were performed, with the presence of

myopia as the dependent outcome variable. Likelihood ratio tests were performed to compare models. Odds ratios (_OR_) and 95% CI are presented, with the significance level set at 0.05. All

statistical analyses were performed using R statistical software, version 3.4.036 including the packages MASS35 and gmodels37. RESULTS REFRACTIVE ERRORS Table 1 shows an overview of the

prevalence of refractive errors by age and sex, independent of ethnicity (a) and for those defined as Norwegians (b). The overall prevalence of hyperopia and myopia was 55.4% and 13.4%,

respectively. All results are from here on related to those defined as Norwegians. The prevalence of hyperopia and myopia in Norwegians was 56.7% and 12.7%, respectively. Figure 2 shows the

leptokurtic distribution of SER [D] for 16–19-year-old Norwegians. The SER mean (±SD) was +0.55 (±1.29) D and median was +0.61 D (range: −6.45–7.71 D). Myopia was more prevalent among

females than males [15.6% versus 8.6%, Fisher’s exact test, _p_ = 0.046]. The prevalence of hyperopia decreased with age, with the prevalence of myopia increasing in parallel (Table 1b,

column 6 and 8). However, the prevalence of high myopia, defined as SER ≤ −6.00 D, was very low, at 0.5% (CI: 0.1–1.8%). In contrast, the prevalence of moderate to high hyperopia, defined as

SER ≥ + 2.00 D, was higher, at 6.4% (CI: 4.2–9.2%). Refractive astigmatism (≥1.00 DC) was found in 8.9% (CI: 6.3–12.2%) and anisometropia (≥1.00 D) in 3.6% (CI: 2.0–5.9%) of participants.

OCULAR BIOMETRY AND BODY HEIGHT Table 2 shows mean AL, CR and AL/CR categorized by age, sex, and refractive error. Mean AL was significantly longer (23.66 vs. 23.28 mm, _t_(391) = −4.46, _p_

< 0.001) and mean corneal curvature (CR) was significantly flatter (7.87 vs. 7.78 mm, _t_(305) = −3.00, _p_ = 0.003) in males compared with females. Overall, AL and CR were highly

correlated (Pearson; _r_ = 0.53 in females, _r_ = 0.69 in males, _p_ < 0.001), and both AL and AL/CR were significantly negatively correlated with SER in both males and females (AL: _r_ =

−0.62, (females), _r_ = −0.47 (males), _p_ < 0.001; AL/CR: _r_ = −0.84 (females), _r_ = −0.77 (males), _p_ < 0.001). The mean height of participants was 172.2 (±8.7) cm, with males

being on average taller than females [179.2 (±7.1) cm vs. 167.3 (±6.0) cm, _t_(309) = 17.3, _p_ < 0.001]. Height correlated with AL overall (Pearson; _r_ = 0.28, _p_ < 0.001) and in

females (Pearson; _r_ = 0.23, _p_ < 0.001), but not in males (Pearson; _r_ = 0.14, _p_ = 0.08). Height did not correlate with SER. OUTDOOR AND INDOOR ACTIVITY TIME Times spent doing

outdoor and indoor activities were calculated for the subset of Norwegian participants who answered all questions related to time spent on various activities. Although this subgroup

represented only 68% of the total group, there were no differences between this smaller sample (_n_ = 269) and the whole sample of Norwegian participants (_n_ = 393) in prevalence of myopia

(12.3% vs. 12.7%), emmetropia (30.9% vs. 30.5%) or hyperopia [56.9% vs. 56.9%; _χ_2(2) = 0.03, _p_ = 0.984]. These participants reported to spend, on average, 3.8 (±1.8) and 10.5 (±2.4)

hours per day outdoors and indoors, respectively. Most of the participants (93%) reported staying indoors in their school recess time. Myopes spent, on average, less time doing outdoor sport

per day [0.93 (±0.8) h] than non-myopes [emmetropes and hyperopes combined: 1.32 (±1.0) h; _t_(267) = −2.24, _p_ = 0.03], but total time spent outdoors was not associated with myopia

[myopes: 3.65 (±1.5) h; non-myopes: 3.81 (±1.9) h; _t_(267) = 0.47, _p_ = 0.64], neither was time spent on other activities. The hours spent on various indoor or outdoor activities also

showed no significant correlations with either SER, astigmatism, AL or AL/CR-ratio. Females and males spent, on average, the same amount of time outdoors [females: 3.71 (±1.7) h; males: 3.91

(±2.0) h] and indoors [females: 10.68 (±2.3) h; males: 10.26 (±2.4) h]. More than 97% of the students had both their own smart phone and laptop for use at school and for homework. The time

spent using NED each day was the same for females and males [females: 5.01 (±1.5) h; males: 4.97 (±1.5) h]. Table 3 shows the models from the multivariate logistic regression, with myopia as

the outcome variable, sex as potential confounder, and mean hours of different indoor and outdoor activities as the predictors (Model A). Likelihood ratio tests were used for manual

backward selection (Model B). Model B confirmed a lack of significant association of myopia with indoor activities, but showed myopia to be associated with less time spent on outdoor sport

(_OR_ = 0.51, CI: 0.30–0.82, _p_ = 0.007) and more time spent on other outdoor activities (_OR_ = 1.49, CI: 1.04–2.15, _p_ = 0.030), after adjustment for sex. Table 4 shows that 94% and 64%

reported to spend half or more of the day outdoors in the summer and Easter holidays, respectively. More myopes (14%) than non-myopes (4%) reported to spend most of their time indoors during

the summer holidays (Fisher’s exact test, _p_ = 0.01), with no difference for the other holidays. DISCUSSION This is the first report on refractive errors in a representative sample of

adolescents in Southeast Norway, with hyperopia found to be the most common type of refractive error. How does the refractive error profile of this adolescent population compare with other

adolescent populations? The prevalence of moderate to high hyperopia (SER ≥ + 2.00 D) in this sample (6.4%) is higher than that reported for adolescents in both Asia (0.5–4.0%)38,39,40 and

Australian European Caucasians (2.0%)5, but lower than among white adolescents in the UK (17.7%)41. Comparative data from other published studies on myopia prevalence are summarized in Table

5, with matched myopia definition. The prevalence of myopia is comparable with, albeit slightly lower than for Australian European Caucasians in Sydney5 and white adolescents in the UK41.

It was lower than the 27.4% point estimate for myopia in the 15–19-year age group across Europe, calculated by random-effect meta-analysis and age-standardization by Williams _et al_.42

(mean SER for the two eyes ≤−0.75 D). The prevalence of myopia was also lower than that reported in a study of Swedish 12–13-year-olds43, though that study’s use of tropicamide 0.5% for

accommodation control may have resulted in an artificially high myopia prevalence. The prevalence of myopia observed in the Southeast-Norwegian 16-year-olds is only slightly higher than that

reported for 1-year-younger adolescents in rural Nepal, Iran and rural India44,45,46 (all considerably lower HDI than Norway). Noteworthy, the prevalence of myopia is considerably lower

than that generally reported for adolescents in rural and urban parts of Asia12,38,39,40,47,48,49 [with comparable or lower human development index (HDI) than Norway]24, and Chile50

(considerably lower HDI than Norway). The ocular biometry data are consistent with the low myopia prevalence, with shorter axial lengths and lower average AL/CR than groups with higher

myopia prevalence [cf. Table 2 with Lu _et al_.51 and Li _et al_.52]. While the prevalence of myopia is reported to have been rising around the world, a similar trend in Southeast Norway

appears to be absent. Specifically, a 1971 study of 12–14-year-old Norwegian children in West Norway (latitude 60.4°) reported similar cycloplegic SERs to that found here (at latitude

59.7–60.0°), and similarly low myopia prevalence (SER ≤ −1.0) of 13.7% (Table 5)53. Interestingly, Fledelius reported stability in the myopia prevalence of Danish medical students over the

period 1968–199854. Moreover, the low rate of high myopia (0.5%; SER ≤ −6 D) observed here and the reported higher myopia prevalence in 21-year-olds in mid-Norway [myopia prevalence (SER ≤

−0.25) was 33% in the general population, latitude 63.4°]55 suggest that myopia onset is significantly delayed in Norwegians compared with East-Asians and some other Europe based

populations12,38,39,41,43,47. The narrow range in refractive errors, higher prevalence of emmetropia with a hyperopic mean SER, coupled with a low prevalence of anisometropia and astigmatism

lend support to this suggestion56,57,58. A further increase in myopia prevalence may be expected when the adolescents enter higher education55. The education system in Norway is classified

as high-performing26. The adolescents in this study spent >10 hours per day indoors doing near work including working on NED for >5 hours per day, which was comparable with the amount

of time spent on NED reported in a study of sleep in 16–19-year-olds in West Norway (latitude 60.4°, n = 9,846)59. But, time spent on near work was not associated with myopia, as reported by

others60,61, neither was total time spent on outdoor activities in the winter — the multivariate analyses showed that the association for other activities outdoors outweighed that of doing

sports outdoors. There was, however, an association between myopia and less time spent outdoors in the summer holiday. Interestingly, the mean time spent outdoors in the winter [3.79 (±1.8)

hours per day; data collection was February–March] was similar to that reported for East-Asian adolescents [_n_ = 267; mean 3.79 (±1.9) hours per day]12 in Singapore, where there is no

difference in daylight hours (12 hours per day) between seasons (Fig. 1). This parallel raises the question for Norwegian adolescents, as to why the potential negative consequences of

limited daylight exposure during the long autumn-winter period, when there are fewer than 12 hours daylight per day (174 days, including 82 days in November–January with only 6–8 hours

daylight per day), do not override the potential positive benefits of the long days during the shorter summer period (124 days with 15–19 hours daylight per day). Note that there is a

ceiling effect to the benefits of long summer days, since several hours of the daylight are in the late evening or early hours of the morning when children and adolescents sleep62,63.

Norwegian children most likely only have access to about 12 hours of the daylight available to them in the spring-summer period (Fig. 1), which is comparable to what the children in

Singapore have access to every day of the year. Can the difference in myopia prevalence between Norwegian and for example Singaporean adolescents (12.7% versus 69.5%12) be down to the

increased time Norwegian adolescents spend outdoors in the 8-week summer holiday only? Considering the effect on myopia progression reported from the outdoor activity clinical trials in East

Asia18, it seems unlikely that this can be the case. This raises the further question in relation to whether exposure to daylight _per se_ is the most important factor in the protective

effect of outdoor activity [cf. Guggenheim _et al_.64]. Could the state of being well adapted to seasonal variations (circannual rhythms) be as important for coordinated eye growth as it is

for general health65? Is this to a larger degree preserved in Norwegian adolescents, because of more outdoor time since early childhood? Being outdoors is a part of the Norwegian culture and

a major part of growing up. For example, children in Norwegian kindergartens are reported to spend 2 hours per day outdoors in the winter and at least 4 hours in the summer66. Furthermore,

children are required to stay outdoors during school recess (three to five breaks that accumulates to at least 1 hour per day) all the way through primary school (6–12 years of age), and all

year long67. Pre-adolescent children spend on average an additional 2 hours outdoors per day after school68. These exposure patterns are quite different from those of children attending

East-Asian schools where recess time usually is spent indoors13,17,18. It has been suggested that 2 hours spent outdoors per day is needed to prevent onset of myopia17, with outdoor

activities having a stronger protective effect in younger children (age 6 years vs. age 11–12 years)19,69. Our data for Norwegian adolescents represent further supportive evidence from a

real-life experiment. Nonetheless, it is also possible that the early onset of myopia as observed in many East Asian populations may be driven by genetic predisposition more than by

environmental factors10,30. Sex differences in myopia prevalence have been reported previously70,71,72. As in past studies, females were found to have a higher prevalence of myopia than

males. There was a significant correlation between AL and height in females, but not males, which may be related to the age of onset of the childhood growth spurt. Specifically, girls

usually show an earlier growth spurt, starting approximately two years ahead of boys73,74,75. There is a parallel here with myopia onset for females, which has been reported to be two years

ahead of males54,75. The implication of the earlier onset of myopia in females is that they have a higher risk for developing larger myopic errors and secondary ocular pathology — indeed, as

reported for older age groups76,77,78. Our study had several limitations. The sample size could have been larger with an even higher response rate, but this is comparable to other studies

when considering the narrow age range (Table 5). The population studied may be biased in its representation, although we have shown our sample to be representative for the region of Norway

from which it was drawn (see Supplementary Material). It was not representative in terms of sex, with a slightly higher number of females, but considering that more females were myopic this,

if anything, might suggest that the true overall prevalence of myopia may be lower. The use of questionnaires for quantifying time outdoors is common in studies of refractive

errors11,69,79, even though there are inherent limitations associated with such an instrument compared with objective measures, for example wearable light meters80. This includes analytical

problems arising from the use of categorical responses to a continuous event. Nonetheless, the comparisons made above were limited to studies that also made use of questionnaires for

quantifying time in the same way. In summary, this cross-sectional study of adolescents in Southeast Norway revealed hyperopia to be the most common refractive error, with the prevalence of

myopia being quite low, despite the few daylight hours in the autumn-winter period and high levels of indoor activity and near work. While the origin of refractive errors is likely

multifactorial56, a dose-response relationship between daylight (outdoor exposure) and ocular axial elongation alone cannot explain the low prevalence in myopia, anisometropia and

astigmatism in this population. Genetic and environmental risk factors may impact how refractive errors develop differently81, and our results may point to a lower genetic predisposition to

myopia in this population. Alternatively, perhaps there is a particular combination of genetic predisposition, circannual adaptation, timing and pattern of exposure to myopia-generating

environmental triggers that are effective in protecting the population at this latitude against myopia. DATA AVAILABILITY Supplementary data on the community profile and demographics, a more

detailed summary of refractive errors, time spent on indoor and outdoor activities, and refractive errors of non-Norwegians (n = 46) are available at usn.figshare.com

[https://doi.org/10.23642/usn.6022790]. REFERENCES * Pan, C. W., Dirani, M., Cheng, C. Y., Wong, T. Y. & Saw, S. M. The age-specific prevalence of myopia in Asia: a meta-analysis.

_Optom. Vis. Sci._ 92, 258–266, https://doi.org/10.1097/opx.0000000000000516 (2015). Article PubMed Google Scholar * Lin, L. L., Shih, Y. F., Hsiao, C. K. & Chen, C. J. Prevalence of

myopia in Taiwanese schoolchildren: 1983 to 2000. _Ann. Acad. Med. Singapore_ 33, 27–33 (2004). PubMed CAS Google Scholar * Holden, B. A. _et al_. Global Prevalence of Myopia and High

Myopia and Temporal Trends from 2000 through 2050. _Ophthalmology_ 123, 1036–1042, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ophtha.2016.01.006 (2016). Article PubMed Google Scholar * Williams, K. M. _et

al_. Increasing Prevalence of Myopia in Europe and the Impact of Education. _Ophthalmology_ 122, 1489–1497, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ophtha.2015.03.018 (2015). Article PubMed PubMed

Central Google Scholar * French, A. N., Morgan, I. G., Burlutsky, G., Mitchell, P. & Rose, K. A. Prevalence and 5- to 6-year incidence and progression of myopia and hyperopia in

Australian schoolchildren. _Ophthalmology_ 120, 1482–1491, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ophtha.2012.12.018 (2013). Article PubMed Google Scholar * Saw, S. M., Gazzard, G., Shih-Yen, E. C.

& Chua, W. H. Myopia and associated pathological complications. _Ophthalmic Physiol. Opt._ 25, 381–391, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-1313.2005.00298.x (2005). Article PubMed Google

Scholar * Mirshahi, A. _et al_. Myopia and level of education: results from the Gutenberg Health Study. _Ophthalmology_ 121, 2047–2052, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ophtha.2014.04.017 (2014).

Article PubMed Google Scholar * Rose, K. A., French, A. N. & Morgan, I. G. Environmental Factors and Myopia: Paradoxes and Prospects for Prevention. _Asia Pac J Ophthalmol_ 5,

403–410, https://doi.org/10.1097/apo.0000000000000233 (2016). Article Google Scholar * Pan, C.-W., Ramamurthy, D. & Saw, S.-M. Worldwide prevalence and risk factors for myopia.

_Ophthalmic Physiol. Opt._ 32, 3–16, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-1313.2011.00884.x (2012). Article PubMed Google Scholar * Jin, Z. B. _et al_. Trio-based exome sequencing arrests de

novo mutations in early-onset high myopia. _Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA_ 114, 4219–4224, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1615970114 (2017). Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar * Rose, K. A.

_et al_. Outdoor activity reduces the prevalence of myopia in children. _Ophthalmology_ 115, 1279–1285, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ophtha.2007.12.019 (2008). Article PubMed Google Scholar

* Dirani, M. _et al_. Outdoor activity and myopia in Singapore teenage children. _Br. J. Ophthalmol._ 93, 997–1000, https://doi.org/10.1136/bjo.2008.150979 (2009). Article PubMed CAS

Google Scholar * Jin, J. X. _et al_. Effect of outdoor activity on myopia onset and progression in school-aged children in northeast China: the Sujiatun Eye Care Study. _BMC Ophthalmol._

15, 73, https://doi.org/10.1186/s12886-015-0052-9 (2015). Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Jones-Jordan, L. A. _et al_. Time outdoors, visual activity, and myopia

progression in juvenile-onset myopes. _Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci._ 53, 7169–7175, https://doi.org/10.1167/iovs.11-8336 (2012). Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Li, S. M.

_et al_. Time Outdoors and Myopia Progression Over 2 Years in Chinese Children: The Anyang Childhood Eye Study. _Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci._ 56, 4734–4740,

https://doi.org/10.1167/iovs.14-15474 (2015). Article PubMed Google Scholar * Guggenheim, J. A. _et al_. Time outdoors and physical activity as predictors of incident myopia in childhood:

a prospective cohort study. _Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci._ 53, 2856–2865, https://doi.org/10.1167/iovs.11-9091 (2012). Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Wu, P. C., Tsai,

C. L., Wu, H. L., Yang, Y. H. & Kuo, H. K. Outdoor activity during class recess reduces myopia onset and progression in school children. _Ophthalmology_ 120, 1080–1085,

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ophtha.2012.11.009 (2013). Article PubMed Google Scholar * He, M. _et al_. Effect of Time Spent Outdoors at School on the Development of Myopia Among Children in

China: A Randomized Clinical Trial. _JAMA_ 314, 1142–1148, https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2015.10803 (2015). Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar * Xiong, S. _et al_. Time spent in outdoor

activities in relation to myopia prevention and control: a meta-analysis and systematic review. _Acta Ophthalmol_ 96, 551–556, https://doi.org/10.1111/aos.13403 (2017). Article Google

Scholar * Gwiazda, J., Deng, L., Manny, R. & Norton, T. T. Seasonal variations in the progression of myopia in children enrolled in the correction of myopia evaluation trial. _Invest.

Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci._ 55, 752–758, https://doi.org/10.1167/iovs.13-13029 (2014). Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Fulk, G. W., Cyert, L. A. & Parker, D. A. Seasonal

variation in myopia progression and ocular elongation. _Optom. Vis. Sci._ 79, 46–51 (2002). Article PubMed Google Scholar * Morgan, I. G. & Rose, K. A. Myopia and international

educational performance. _Ophthalmic Physiol. Opt._ 33, 329–338, https://doi.org/10.1111/opo.12040 (2013). Article PubMed Google Scholar * Cornwall, C., Horiuchi, A. & Lehman, C.

_NOAA Solar Calculator_, https://www.esrl.noaa.gov/gmd/grad/solcalc/sunrise.html (2017). * The United Nations Development Programme (UNDP). Human Development Report 2016, Human Development

for Everyone. (New York, USA, 2016). * Statistics Norway. _Kindergartens, 2016_, _final figures_, https://www.ssb.no/en/utdanning/statistikker/barnehager/aar-endelige/2017-03-21-content

(2017). * OECD. _PISA 2015, PISA, Results in Focus_. (OECD Publisher, 2016). * OECD. _Students, Computers and Learning: Making the Connection_. (PISA, OECD Publishing, 2015). * Ramamurthy,

D., Lin Chua, S. Y. & Saw, S. M. A review of environmental risk factors for myopia during early life, childhood and adolescence. _Clin. Exp. Optom._ 98, 497–506,

https://doi.org/10.1111/cxo.12346 (2015). Article PubMed Google Scholar * Tkatchenko, A. V. _et al_. APLP2 Regulates Refractive Error and Myopia Development in Mice and Humans. _PLoS

Genet_ 11, e1005432, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgen.1005432 (2015). Article PubMed PubMed Central CAS Google Scholar * Fan, Q. _et al_. Childhood gene-environment interactions and

age-dependent effects of genetic variants associated with refractive error and myopia: The CREAM Consortium. _Sci. Rep._ 6, 25853, https://doi.org/10.1038/srep25853 (2016). Article ADS

PubMed PubMed Central CAS Google Scholar * Statistics Norway. _Population and land area in urban settlements, 1 January 2016_, https://www.ssb.no/en/befolkning/statistikker/beftett

(2017). * Statistics Norway. _Population and area, by municipality (SY 57)_, http://www.ssb.no/303784/population-and-area-by-municipality-sy-57 (2017). * Statistics Norway. _Tabell: 07459:

Folkemengde, etter kjønn og ettårig alder. 1. januar (K) [Table: 07459: Population, by sex and age (1-year step). 1 January (M)]_,

https://www.ssb.no/statistikkbanken/selectvarval/Define.asp?subjectcode=&ProductId=&MainTable=NY3026&nvl=&PLanguage=0&nyTmpVar=true&CMSSubjectArea=befolkning&KortNavnWeb=folkemengde&StatVariant=&checked=true

(2016). * Ojaimi, E. _et al_. Methods for a population-based study of myopia and other eye conditions in school children: the Sydney Myopia Study. _Ophthalmic Epidemiol._ 12, 59–69,

https://doi.org/10.1080/09286580490921296 (2005). Article PubMed Google Scholar * Venables, W. N. & Ripley, B. D. _Modern Applied Statistics with S_. Fourth edn, (Springer, 2002). *

R: A language and environment for statistical computing (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria, 2016). * gmodels: Various R Programming Tools for Model Fitting (2015). *

Zhao, J. _et al_. Refractive Error Study in Children: results from Shunyi District, China. _Am. J. Ophthalmol._ 129, 427–435 (2000). Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar * He, M., Huang,

W., Zheng, Y., Huang, L. & Ellwein, L. B. Refractive error and visual impairment in school children in rural southern China. _Ophthalmology_ 114, 374–382,

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ophtha.2006.08.020 (2007). Article PubMed Google Scholar * Murthy, G. V. _et al_. Refractive error in children in an urban population in New Delhi. _Invest.

Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci._ 43, 623–631 (2002). PubMed CAS Google Scholar * McCullough, S. J., O’Donoghue, L. & Saunders, K. J. Six Year Refractive Change among White Children and Young

Adults: Evidence for Significant Increase in Myopia among White UK Children. _PLoS One_ 11, e0146332, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0146332 (2016). Article PubMed PubMed Central

CAS Google Scholar * Williams, K. M. _et al_. Prevalence of refractive error in Europe: the European Eye Epidemiology (E(3)) Consortium. _Eur. J. Epidemiol._ 30, 305–315,

https://doi.org/10.1007/s10654-015-0010-0 (2015). Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Villarreal, M. G., Ohlsson, J., Abrahamsson, M., Sjostrom, A. & Sjostrand, J.

Myopisation: the refractive tendency in teenagers. Prevalence of myopia among young teenagers in Sweden. _Acta Ophthalmol. Scand._ 78, 177–181 (2000). Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar *

Pokharel, G. P., Negrel, A. D., Munoz, S. R. & Ellwein, L. B. Refractive Error Study in Children: results from Mechi Zone, Nepal. _Am. J. Ophthalmol._ 129, 436–444 (2000). Article

PubMed CAS Google Scholar * Fotouhi, A., Hashemi, H., Khabazkhoob, M. & Mohammad, K. The prevalence of refractive errors among schoolchildren in Dezful, Iran. _Br. J. Ophthalmol._ 91,

287–292, https://doi.org/10.1136/bjo.2006.099937 (2007). Article PubMed Google Scholar * Dandona, R. _et al_. Refractive error in children in a rural population in India. _Invest.

Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci._ 43, 615–622 (2002). PubMed Google Scholar * Qian, D. J. _et al_. Myopia among school students in rural China (Yunnan). _Ophthalmic Physiol. Opt._ 36, 381–387,

https://doi.org/10.1111/opo.12287 (2016). Article PubMed Google Scholar * He, M. _et al_. Refractive error and visual impairment in urban children in southern china. _Invest. Ophthalmol.

Vis. Sci._ 45, 793–799 (2004). Article PubMed Google Scholar * Goh, P. P., Abqariyah, Y., Pokharel, G. P. & Ellwein, L. B. Refractive error and visual impairment in school-age

children in Gombak District, Malaysia. _Ophthalmology_ 112, 678–685, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ophtha.2004.10.048 (2005). Article PubMed Google Scholar * Maul, E., Barroso, S., Munoz, S.

R., Sperduto, R. D. & Ellwein, L. B. Refractive Error Study in Children: results from La Florida, Chile. _Am. J. Ophthalmol._ 129, 445–454 (2000). Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar *

Lu, T. L. _et al_. Axial Length and Associated Factors in Children: The Shandong Children Eye Study. _Ophthalmologica_ 235, 78–86, https://doi.org/10.1159/000441900 (2016). Article PubMed

Google Scholar * Li, S. M. _et al_. Corneal Power, Anterior Segment Length and Lens Power in 14-year-old Chinese Children: the Anyang Childhood Eye Study. _Sci. Rep._ 6, 20243,

https://doi.org/10.1038/srep20243 (2016). Article ADS PubMed PubMed Central CAS Google Scholar * Larsen, J. S. The sagittal growth of the eye. 1. Ultrasonic measurement of the depth of

the anterior chamber from birth to puberty. _Acta Ophthalmol. (Copenh)_ 49, 239–262 (1971). Article CAS Google Scholar * Fledelius, H. C. Myopia profile in Copenhagen medical students

1996–98. Refractive stability over a century is suggested. _Acta Ophthalmol. Scand._ 78, 501–505 (2000). Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar * Kinge, B., Midelfart, A. & Jacobsen, G.

Refractive errors among young adults and university students in Norway. _Acta Ophthalmol. Scand._ 76, 692–695 (1998). Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar * Flitcroft, D. I. Emmetropisation

and the aetiology of refractive errors. _Eye_ 28, 169–179, https://doi.org/10.1038/eye.2013.276 (2014). Article PubMed PubMed Central CAS Google Scholar * Deng, L. & Gwiazda, J. E.

Anisometropia in children from infancy to 15 years. _Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci._ 53, 3782–3787, https://doi.org/10.1167/iovs.11-8727 (2012). Article PubMed PubMed Central Google

Scholar * Ehrlich, D. L. _et al_. Infant emmetropization: longitudinal changes in refraction components from nine to twenty months of age. _Optom. Vis. Sci._ 74, 822–843 (1997). Article

PubMed CAS Google Scholar * Hysing, M. _et al_. Sleep and use of electronic devices in adolescence: results from a large population-based study. _BMJ Open_ 5,

https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2014-006748 (2015). * Lu, B. _et al_. Associations between near work, outdoor activity, and myopia among adolescent students in rural China: the Xichang

Pediatric Refractive Error Study report. _Arch. Ophthalmol._ 127, 769–775, https://doi.org/10.1001/archophthalmol.2009.105 (2009). Article PubMed Google Scholar * Tan, N. W. _et al_.

Temporal variations in myopia progression in Singaporean children within an academic year. _Optom. Vis. Sci._ 77, 465–472 (2000). Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar * Galland, B. C.,

Taylor, B. J., Elder, D. E. & Herbison, P. Normal sleep patterns in infants and children: a systematic review of observational studies. _Sleep Med. Rev._ 16, 213–222,

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.smrv.2011.06.001 (2012). Article PubMed Google Scholar * Hysing, M., Pallesen, S., Stormark, K. M., Lundervold, A. J. & Sivertsen, B. Sleep patterns and

insomnia among adolescents: a population‐based study. _J. Sleep Res._ 22, 549–556, https://doi.org/10.1111/jsr.12055 (2013). Article PubMed Google Scholar * Guggenheim, J. A. _et al_.

Assumption-free estimation of the genetic contribution to refractive error across childhood. _Mol. Vis._ 21, 621–632 (2015). PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Evans, J. A. &

Davidson, A. J. In _Prog. Mol. Biol. Transl. Sci_. Vol. 119 (ed Martha U. Gillette) 283–323 (Academic Press, 2013). * Moser, T. & Martinsen, M. The outdoor environment in Norwegian

kindergartens as pedagogical space for toddlers’ play, learning and development. _European Early Childhood Education Research Journal_ 18, 457–471,

https://doi.org/10.1080/1350293X.2010.525931 (2010). Article Google Scholar * Vaage, O. F. _Tidene skifter. Tidsbruk 1971–2010 [Time use 1971–2010]_. (Statistisk sentralbyrå, 2012). *

Vaage, O. F. T. 2010. Utendørs 2 1/2 time - menn mer enn kvinner [Time use 2010. Outdoors 2 1/2 hour - males more than females]. _Samfunnsspeilet_ 26, 37–42 (2012). Google Scholar * Shah,

R. L., Huang, Y., Guggenheim, J. A. & Williams, C. Time Outdoors at Specific Ages During Early Childhood and the Risk of Incident Myopia. _Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci._ 58, 1158–1166,

https://doi.org/10.1167/iovs.16-20894 (2017). Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Saw, S. M. _et al_. Incidence and progression of myopia in Singaporean school children.

_Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci._ 46, 51–57, https://doi.org/10.1167/iovs.04-0565 (2005). Article PubMed Google Scholar * Rudnicka, A. R. _et al_. Global variations and time trends in the

prevalence of childhood myopia, a systematic review and quantitative meta-analysis: implications for aetiology and early prevention. _Br. J. Ophthalmol_.

https://doi.org/10.1136/bjophthalmol-2015-307724 (2016). * Congdon, N. _et al_. Visual disability, visual function, and myopia among rural chinese secondary school children: the Xichang

Pediatric Refractive Error Study (X-PRES)–report 1. _Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci._ 49, 2888–2894, https://doi.org/10.1167/iovs.07-1160 (2008). Article PubMed Google Scholar * Liu, Y. X.,

Wikland, K. A. & Karlberg, J. New reference for the age at childhood onset of growth and secular trend in the timing of puberty in Swedish. _Acta Paediatr._ 89, 637–643 (2000). Article

PubMed CAS Google Scholar * Lyu, I. J. _et al_. The Association Between Menarche and Myopia: Findings From the Korean National Health and Nutrition Examination, 2008–2012. _Invest.

Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci._ 56, 4712–4718, https://doi.org/10.1167/iovs.14-16262 (2015). Article PubMed Google Scholar * Yip, V. C. _et al_. The relationship between growth spurts and myopia

in Singapore children. _Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci._ 53, 7961–7966, https://doi.org/10.1167/iovs.12-10402 (2012). Article PubMed Google Scholar * Willis, J. R. _et al_. The Prevalence

of Myopic Choroidal Neovascularization in the United States: Analysis of the IRIS((R)) Data Registry and NHANES. _Ophthalmology_ 123, 1771–1782, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ophtha.2016.04.021

(2016). Article PubMed Google Scholar * Wong, T. Y., Ferreira, A., Hughes, R., Carter, G. & Mitchell, P. Epidemiology and disease burden of pathologic myopia and myopic choroidal

neovascularization: an evidence-based systematic review. _Am. J. Ophthalmol._ 157, 9–25.e12, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajo.2013.08.010 (2014). Article PubMed Google Scholar * Asakuma, T.

_et al_. Prevalence and risk factors for myopic retinopathy in a Japanese population: the Hisayama Study. _Ophthalmology_ 119, 1760–1765, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ophtha.2012.02.034 (2012).

Article PubMed Google Scholar * French, A. N., Ashby, R. S., Morgan, I. G. & Rose, K. A. Time outdoors and the prevention of myopia. _Exp. Eye Res._ 114, 58–68,

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.exer.2013.04.018 (2013). Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar * Alvarez, A. A. & Wildsoet, C. F. Quantifying light exposure patterns in young adult students.

_J Mod Opt_ 60, 1200–1208, https://doi.org/10.1080/09500340.2013.845700 (2013). Article ADS MathSciNet PubMed PubMed Central MATH Google Scholar * Chen, Y., Chang, B. H., Ding, X.

& He, M. Patterns in longitudinal growth of refraction in Southern Chinese children: cluster and principal component analysis. _Sci. Rep._ 6, 37636, https://doi.org/10.1038/srep37636

(2016). Article ADS PubMed PubMed Central CAS Google Scholar * OECD. _PISA 2015 Results (Volume I): Excellence and Equity in Education_. (PISA, OECD Publishing, 2016). * Mullis, I. V.

S., Martin, M. O., Foy, P. & Hooper, M. TIMSS2015 InternationalResults in Mathematics. (TIMSS & PIRLS, International Study Center, Lynch School of Education, Boston College, USA,

2016). * Morgan, I. G., Rose, K. A. & Ellwein, L. B. Is emmetropia the natural endpoint for human refractive development? An analysis of population-based data from the refractive error

study in children (RESC). _Acta Ophthalmol_ 88, 877–884, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1755-3768.2009.01800.x (2010). Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Naidoo, K. S. _et al_.

Refractive error and visual impairment in African children in South Africa. _Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci._ 44, 3764–3770 (2003). Article PubMed Google Scholar Download references

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The authors thank Kenneth Knoblauch for statistical advice and constructive feedback on the manuscript. The study was funded by the University of South-Eastern Norway and

Regional Research Funds: The Oslofjord Fund Norway Grant No. 249049 (RCB). LAH holds a PhD position funded by the Norwegian Ministry of Education and Research. AUTHOR INFORMATION AUTHORS AND

AFFILIATIONS * National Centre for Optics, Vision and Eye Care, Faculty of Health and Social Sciences, University of South-Eastern Norway, Kongsberg, Norway Lene A. Hagen, Jon V. B. Gjelle,

Solveig Arnegard, Hilde R. Pedersen, Stuart J. Gilson & Rigmor C. Baraas Authors * Lene A. Hagen View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar *

Jon V. B. Gjelle View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Solveig Arnegard View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed

Google Scholar * Hilde R. Pedersen View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Stuart J. Gilson View author publications You can also search for

this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Rigmor C. Baraas View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar CONTRIBUTIONS R.C.B. and L.A.H. conceived and

designed the study, analyzed/interpreted the data, wrote the manuscript, and prepared the figures and tables. R.C.B., L.A.H., J.V.B.G., S.A., H.R.P., S.J.G. conducted the experiments,

interpreted data and reviewed the manuscript. CORRESPONDING AUTHOR Correspondence to Rigmor C. Baraas. ETHICS DECLARATIONS COMPETING INTERESTS The authors declare no competing interests.

ADDITIONAL INFORMATION PUBLISHER'S NOTE: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. ELECTRONIC SUPPLEMENTARY

MATERIAL SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION ABOUT REPRESENTATIVENESS IN THE DATA. RIGHTS AND PERMISSIONS OPEN ACCESS This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International

License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source,

provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons

license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by

statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. Reprints and permissions ABOUT THIS ARTICLE CITE THIS ARTICLE Hagen, L.A., Gjelle, J.V.B., Arnegard, S. _et al._ Prevalence and Possible Factors

of Myopia in Norwegian Adolescents. _Sci Rep_ 8, 13479 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-31790-y Download citation * Received: 16 November 2017 * Accepted: 28 August 2018 *

Published: 07 September 2018 * DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-31790-y SHARE THIS ARTICLE Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content: Get shareable

link Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article. Copy to clipboard Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative