Perceived service quality and student satisfaction in higher learning institutions in tanzania

- Select a language for the TTS:

- UK English Female

- UK English Male

- US English Female

- US English Male

- Australian Female

- Australian Male

- Language selected: (auto detect) - EN

Play all audios:

ABSTRACT Despite policy efforts to promote higher learning in Tanzania, reports show persistent student dissatisfaction, revealing the extant inadequate quality measurement models. The study

examined the fundamental elements causing dissatisfaction using an extended SERVQUAL model with additional variables, perceived transparency mediated by trust. Researchers collected

quantitative data from 398 third-year higher learning students. The structural equations modelling result shows that reliability, perceived transparency, and trust in an institution

significantly predict satisfaction. Further, trust partially mediates the influence of perceived transparency on student satisfaction. Evidence from this study suggests that education policy

geared to promote the expertise of service providers and punctuality of service offering, transparency in service offering, and social responsibility of service provision is adequate for

student satisfaction. Future research can look into a cross-level of economic development, groups of students—analysis of satisfaction determinants, and test the transparency—trust-based

SERVIQUAL Model in quality struggling sectors in Tanzania and other developing countries. Also, studies can test how satisfaction mediates the effect of quality on academic performance.

SIMILAR CONTENT BEING VIEWED BY OTHERS THE FACTORS ASSOCIATED WITH TEACHERS’ JOB SATISFACTION AND THEIR IMPACTS ON STUDENTS’ ACHIEVEMENT: A REVIEW (2010–2021) Article Open access 24 April

2023 AN INTEGRATION OF EXPECTATION CONFIRMATION MODEL AND INFORMATION SYSTEMS SUCCESS MODEL TO EXPLORE THE FACTORS AFFECTING THE CONTINUOUS INTENTION TO UTILISE VIRTUAL CLASSROOMS Article

Open access 09 August 2024 RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN PERCEIVED VALUE, STUDENT EXPERIENCE, AND UNIVERSITY REPUTATION: STRUCTURAL EQUATION MODELING Article Open access 03 November 2023 INTRODUCTION

Higher education is the cornerstone of a knowledge-driven economy (Sum and Jessop, 2012). It builds competent human capital and technological capabilities needed for sustainable economic

development (Kruss et al. 2015). More excellent human capital quality attracts FDI (Naanwaab and Diarrassouba, 2016), and its resulting income and job creation effects spur innovation and

self-employment (Amadeo, 2022; Li et al. 2017). Worldwide, governments, including Tanzania, promote higher learning institutions (HLIs) and education. In Tanzania, the HLIs consist of

universities, colleges, and other institutions of higher learning (Tanzania Commission for Universities, [TCU], 2020), offering lower and higher tertiary education. Tanzania’s education

sector consists of private HLIs and public HLIs, all operating under the same regulatory and policy framework. For the public HLIs, the government of Tanzania has made several efforts to

promote access to and enrolment in higher learning. Among the efforts are establishing new public universities and colleges, expanding the existing infrastructures (Mwapachu, 2010), training

a skilled workforce, and providing student loan schemes (Nyahende, 2013). The private HLIs, through private equity and debt, also developed new branches and infrastructures.

Institutionally, efforts include establishing flexible learning modes such as distance learning (Mwilongo, 2015), e-learning systems (Tossy, 2017; Kisanga, 2016), and the establishment of

evening and executive classes. Even though the efforts put in place resulted in increased access to tertiary education and student enrolment, there is hardly mention of the quality of

education offered (Kessy, 2020). Amutabi (2021) shows that in the government policy reforms, the quality of knowledge created in universities has not been a priority but rather enrolment

expansion. As a result, the HLIs lack adequate financial resources for quality enhancement (Johansson and Lundborg, 2021; Mgaiwa, 2018), as required by the standards in Manyaga (2008).

Financial resources are needed to improve the quality of learning facilities in lecture rooms, libraries, books, co-curriculum resources, and internet services (Mgaiwa and Poncian 2016). In

response to the service quality issue, the government of Tanzania assigns education policy and regulatory bodies: The Ministry of Education, Science, and Technology (MoEST), the Tanzania

Commission for Universities (TCU), and the National Council for Technical and Vocational Education and Training (NACTVET) to improve the HLIs service quality (Mgaiwa, 2018) and to ensure the

issue is not jeopardising the quality performance of graduates (Mgaiwa, 2021). Further, the government formulated accreditation and quality assurance policy frameworks in higher learning

institutions (Mgaiwa, 2018). These policy and regulatory frameworks have made positive steps toward improving the quality of education, as TCU (2019) reports the following data. In 2018,

more than 50% of the HLIs were closed or suspended due to quality issues related to infrastructure, teaching materials, syllabi, assessment methods, teaching, and learning platforms. TCU

reports further explain that in 2018, only 24% of the fully-fledged private universities and 19% of private university colleges had a quality assurance unit or directorate or developed a

quality assurance strategy. Also, only 9% of private university colleges had developed a quality assurance policy. Despite the steps, the report shows that students’ dissatisfaction with the

quality of education services provided by HLIs persists (TCU, 2019). The critical challenge in monitoring the quality of education service is the lack of clear and specific indicators of

student’s perceptions of the service quality (Akman and Kopuz, 2020; Magasi et al. 2022; Njau, 2019). The SERVIQUAL Model is vital for measuring quality perception (Saravanan and Rao, 2007).

However, the setting, culture, service type, and level of development affect how the SERVIQUAL Model and customer satisfaction are measured and evaluated (Magasi et al. 2022). This suggests

that the relationship between the SQ model and student satisfaction is context, culture, and service type specific. Thus, empirical findings from certain settings may not be relevant and

applicable in other contexts. Previous studies measured service quality and student satisfaction using the traditional SERVQUAL MODEL (Mashenene, 2019). Few studies have attempted to enrich

the SERVQUAL Model in industries like banking (Ali & Raza, 2017). Studies propound incorporating other variables into the SERVQUAL Model to establish a more comprehensive research model

(Medina and Rufin, 2015; Onditi and Wenchuli, 2017), which is context relevant for effective policy action. As described in the methodology, preliminary analysis of students’ perception of

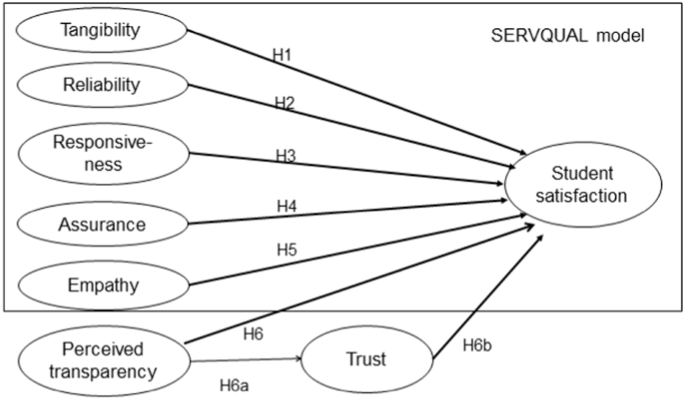

education quality from their institutions has found tangibility, reliability, responsiveness, assurance, empathy, perceived transparency of student services, and trust in the institution to

matter to students’ satisfaction. As a result, the authors modified the SERVQUAL Model by including two more constructs; perceived transparency and students’ trust in an institution. This

research problem is scientifically justified through a preliminary survey, and the chosen variables are based on the students’ perception of service quality. Scant empirical evidence points

to the association of transparency, trust, and satisfaction in government and banking sectors in South Korea and Denmark (Kim and Lee, 2012; Eskildsen and Kristensen, 2007; Park and

Blenkinsopp, 2011; Porumbescu, 2017). The transparency and trust constructs in the education sector have not been studied as one of the SQ model dimensions. This study seeks to contribute to

knowledge by testing how a modified SQ model relates to service quality and HLI’s customer satisfaction in education. This study explains how the Tanzanian context can enhance HLI students’

satisfaction. Specifically, this paper suggests a direct impact of service quality dimensions related to HLI services on students’ satisfaction, and direct and indirect effects are

generated by the perceived transparency of student services and trust in students’ satisfaction. The study uses a modified SQ model to determine the relationship between perceived service

quality and student satisfaction among HLI students in Tanzania. REVIEW OF LITERATURE Despite the government’s efforts to address the service quality issues, students’ complaints are

persistent (Jamii Forum, 2020). Many studies relating perceived service quality and student satisfaction in Tanzania target diploma and second and third-year degree students from one

institution (Magasi et al. 2022; Mashenene, 2019; Mbise, 2015; Mwongoso et al. 2015; Mbise et al., 2013; Mbise and Tuninga, 2013). To the authors’ knowledge, one study in Tanzania studied

five HLIs (Magasi et al. 2022). Most service quality and satisfaction studies were conducted only in one or two local colleges (Mashenene, 2019). Hence, extant studies’ results cannot

represent the HLIs’ student population. The current study targeted students from fourteen (14) HLIs located in the coastal zone of Tanzania, improving the sample’s representativeness to the

population of HLIs in the country. Many extant studies acknowledge the link between service quality and customer satisfaction. Mashenene (2019), Mbise (2015), and Mwongoso et al. (2015) used

the traditional SERVQUAL Model. Other studies modified the Model with the new variables in banking and education (Ali and Raza, 2017; Raza et al. 2020; Hwang and Choi, 2019; Magasi et al.

2022). Researchers used transparency and trust in studies on citizens’ satisfaction with government services in South Korea (Kim and Lee, 2012; Porumbescu, 2017) and European banking

services (Eskildsen and Kristensen, 2007). To the researchers’ knowledge, this is the first study to enrich the SERVQUAL Model with variables, perceived transparency, and trust in education.

Hwang and Choi (2019) evaluated the structural links between service quality, student satisfaction, institutional image, and behavioural intention at higher education institutions in South

Korea. The SEM analysis revealed that students were happy with tangibles, dependabilities, responsiveness, empathy, and certainty. In addition, the findings revealed that student

satisfaction and perceived institutional image were directly impacted by service quality. The results also showed that behavioural intention was directly influenced by students’ perceptions

of the institutional image and level of satisfaction. Magasi et al. (2022) re-examined the traditional SERVQUAL Model by adding a new variable, compliance in Tanzanian higher education, and

all variables were significant predictors. In banking, Ali and Raza (2017) demonstrated that compliance positively affects customer satisfaction in the Pakistani banking sector by

integrating it into the five traditional SERVQUAL characteristics. The justification is that improving the quality of the services depends on effective and accurate compliance with the

established industry laws and standards, including policies, regulations, procedures, and architectures. In Pakistan, Raza et al. (2020) found that service quality is the foundation for how

customers perceive online banking and how it interacts and functions with other online services. Some studies related transparency and trust with citizen satisfaction with government

services in South Korea and European banking products. Kim and Lee (2012) found a positive association between government transparency and citizens’ trust and a positive association between

satisfaction and citizens’ assessment of government performance. Eskildsen and Kristensen (2007) found that perceived transparency of banking products and services may influence customers’

satisfaction. Park and Blenkinsopp (2011) found that trust mediates the relationship between corruption and citizens’ satisfaction. Porumbescu (2017) found that increased exposure to

transparency is negatively associated with citizens’ satisfaction with public service provision. The past studies examined the additional variables based on the location of their studies,

culture, and nationalities. Magasi et al. (2022) researched Tanzania, a developing country where the HLIs must comply with laws, regulations, policies, and procedures to deliver quality

education. Ali and Raza (2017) conducted their study in Pakistan since, in a Muslim-majority country, complying with Sharia laws is required; hence they added the compliance variable into

the SERVQUAL. In South Korea, studies were done (Kim and Lee, 2012; Park and Blenkinsopp, 2011; Porumbescu (2017) because the government was adopting various programmes to ensure

accountability, transparency, and trust in government (Kim et al. 2018). For the current study, incorporating transparency and trust variables into the SERVQUAL Model will create knowledge

helpful in improving the quality of tertiary education in Tanzania. Given the situation, the modified Model informs solutions for the persisting tertiary education quality problems.

Empirical evidence from other sectors suggests that customers need information about services and build trust in the service providers’ performance (Park and Blenkinsopp, 2011). Therefore,

the logic and premise behind including transparency and trust in the current study to extend the SERVIQUAL Model is empirically founded. Regarding perceived transparency and trust in an

institution, the logic is that openness to customers about the service process wins their trust, which leads to satisfaction. The current study fills the research gap by applying the

traditional SERVQUAL Model with two more variables (perceived transparency and trust) relating to perceived service quality and satisfaction in education. It modified the SERVQUAL Model to

address the research questions by establishing two objectives: to examine the direct effect of service quality dimensions (tangibility, reliability, responsiveness, assurance, and empathy)

on students’ satisfaction with the services provided by the HLI; and to examine the direct and indirect effects generated by the perceived transparency of student services and trust in the

institution on students’ satisfaction with the student services provided by the HLI. RESEARCH CONCEPTUAL FRAMEWORK AND HYPOTHESES DEVELOPMENT There exist several models for measuring service

quality in the service industry. Grönroos (1984) claimed that the service quality model is a technical and functional quality-based approach to measuring service quality. Cronin and

Taylor’s (1992) SERVPERF model is a performance-based approach to measuring service quality, and the SERVQUAL Model (Parasuraman et al. 1988) aims to close the gap between customer-perceived

performance (P) and expectations-based (E). The original Grönroos’s (1984) service quality model identifies technical and functional quality as the two primary components of service

quality. Technical quality is related to the availability of competent people, the ability to solve technical problems, and the provision of quality computerised systems (Magasi et al. 2022;

Ramzi et al. 2022; and Yılmaz and Temizkan, 2022). Functional quality refers to how service providers in the HLIs deliver the service, which includes attitude, friendliness, promptness,

courtesy, attentiveness, responsiveness, confidence, and communication (Ali et al. 2017; Magasi et al. 2022; Grönroos, 1984). Later, Gronroos (1990) modified the Model by explaining the

relationship between technical quality, functional quality, and service provider image to assess the existing gap between customer expectations of the service and customer experience while

receiving assistance. Nonetheless, considering the technical quality of service is not easy for the customer (Magasi et al. 2022). For example, to the students, evaluating the teacher’s

technical competence is tricky for the student (Gronroos, 1990). Despite the shortcomings of Grönroos’ (1984) service quality model, the scholar’s seminal work is a foundation for developing

other service quality models. Parasuraman et al. (1988) introduced the SERVQUAL Model to explain how respondents rate the service provider’s tangible and intangible service performance—from

the perspective dimensions of tangibility, reliability, responsiveness, assurance, and empathy. In the study context, the SERVQUAL Model assesses respondents’ reactions to the sufficiency

of tangible equipment such as computers, classrooms, labs, and substantial resources like library resources, printing materials, internet connections, and other teaching aids to help

students learn curricular and non-curricular knowledge. In adapting the dimension’s definition explained by the SERVQUAL Model, this study defines service quality dimensions as shown in

Table 1. This study adopts the SERVQUAL framework due to the Model’s capability to solve most of the problems related to current respondents’ satisfaction and adds transparency and trust to

modify it. The transparency of an organisation in offering its service builds customers’ trust, which eventually influences their satisfaction directly and indirectly (Medina and Rufin,

2015). Few studies have examined how transparency, trust, and satisfaction related to SERVQUAL variables cohesively (Alzahrani et al. 2018; Anantha et al., 2012; Arshad and Khurram, 2020;

Denhardt and Denhardt, 2009; Gracia and Arino, 2015; Hwang and Choi, 2019; Medina and Rufin, 2015; Sfenrianto et al. 2018; Thomas et al. 2015). TANGIBILITY, RELIABILITY, RESPONSIVENESS,

ASSURANCE, EMPATHY, AND SATISFACTION Researchers categorise tangibility in tangible equipment (such as computers, projectors, and labs), material resources (constructions, fixtures, teaching

space, location), and actual reading and learning resources (such as library resources, internet access, and printed university materials). Since services are, by their very nature,

intangible, physical elements allow people to judge a service by what they see. The term "tangibility features" in HLIs refers to the items that students can observe to evaluate a

service since they can contribute to their satisfaction (Magasi et al. 2022; Mashenene, 2019). Similarly, the student will feel more fulfilled if perceived tangibility is higher. The current

authors, therefore, predict that, > H1: Tangibles relate to student satisfaction positively. Students in HLIs hope that their institutions will keep their promises and provide error-free

services, as evidenced by studies conducted in Indonesia (Wijaya et al. 2021); Malaysia (Nicholas et al. 2022) and Tanzania (Magasi et al. 2022; Mashenene, 2019). Similarly, the current

authors anticipate a positive relationship between reliability and satisfaction or, > H2: Reliability relates to student satisfaction positively. The results of past studies carried out

in Indonesia (Wijaya et al. 2021); Malaysia (Nicholas et al. 2022), and Tanzania (Magasi et al. 2022; Mashenene, 2019) show that student’s satisfaction increase when the HLIs academic and

administrative staffs are willing to provide valuable and quick service to students. Therefore, the currently studied HLIs staff’s responsiveness is expected to be positively related to

student satisfaction or, > H3: Responsiveness relates to student satisfaction positively. In the SERVQUAL Model, assurance relates to the respondent’s assessment of the service provider’s

knowledge, courtesy, and capacity to motivate the respondents to establish trust and confidence (Parasuraman et al. 1988). In other words, a service provider’s graciousness, courtesy,

approachability, and knowledge capacity are important (Pollack, 2008) for the service providers to build consumer trust and confidence (Zeithaml et al. 2006). The following service quality

studies in HLIs support the positive relationship—Wijaya et al. 2021; Nicholas et al. 2022; Magasi et al. 2022; Mashenene, 2019; as such, this study predicts that, > H4: Assurance relates

to student satisfaction positively. Empathy is a concept that expresses the care and personalised attention that service providers can provide to their clients (Parasuraman et al. 1988).

When a consumer requires customised attention, the customer expects the service provider to become caring. Past service quality studies result in Indonesia (Wijaya et al. 2021), Malaysia

(Nicholas et al. 2022), and Tanzania (Magasi et al. 2022; Mashenene, 2019) support the positive relationship between empathy and satisfaction. Similarly, the current study foresees that the

HLIs’ service provider’s willingness to provide individualised attention to those students who need particular attention increases student satisfaction or, > H5: Empathy positively

influences student satisfaction TRANSPARENCY, TRUST IN THE INSTITUTION, AND SATISFACTION Citizens who are satisfied and their trust are dependable predictors of successful government (Van de

Walle, 2018). Past studies’ results support that satisfaction and trust are related to transparency. For example, service quality studies in Greek (Solakis et al. 2022); Spain (Ramírez and

Tejada, 2022); Chile (Thelen, and Formanchuk, 2022); Indonesia (Honora et al. 2022); Finland (Kumar et al. 2021); German (Hofmann and Strobel, 2020); Libya (Vandewalle, 2018); and Spain

(Medina and Rufin, 2015) show that transparency related to satisfaction positively. Researchers generally define transparency as the extent to which an organisation discloses information to

its stakeholders about its decisions, procedures, and performance (Honora et al. 2022). Transparency, therefore, is helpful in the academic industry in a developing country like Tanzania.

Trust is essential for the overall system’s seamless operation in online and offline information systems research (Capistrano, 2020). The population’s faith in government bodies increases,

and they are likelier to obey the rules and regulations when the trust elements exist (Cheng et al. 2017). Past empirical study results support the positive relationship between transparency

and trust in Indonesia (Honora et al. 2022); Pakistan (Mansoor, 2021); Pakistan (Arshad and Khurram, 2020); and Pakistan (Arshad and Khurram, 2020). Studies carried out by Inan and Çelik

(2018); Shin (2020); Sökmen (2019); Yuan et al. (2020) support the positive relationship between trust and satisfaction. In the review of past studies works, this study; therefore,

transparency, trust, and satisfaction are interrelated, or, > H6: Perceived transparency positively influences student > satisfaction. > H6a: Perceived transparency positively

influences trust in an > institution. > H6b: Trust in an institution positively influence student > satisfaction. Regardless of the ability to monitor or control the other party,

researchers define trust as "the readiness of a party to be vulnerable to the acts of another party based on the anticipation that the other will perform a specific action significant

to the trustor" (Trivedi and Yadav, 2020). According to the researchers’ best knowledge, previous studies indicating that trust is a mediator between transparency and satisfaction in

HLIs are rare. Given the scarcity of literature on trust as a mediator, the consensus in the literature is that student satisfaction is significantly impacted by trust and transparency. A

student who trusts a particular HLI can recommend that HLI to other students; hence, HLIs can identify a positive relation between trust, perceived transparency, and student satisfaction

(Medina and Rufin, 2015). Thus, trust in the context of Tanzanian HLIs is a mediator between perceived transparency and students’ satisfaction. Therefore, this study hypothesised the

following: > H7: Trust can mediate the effect between perceived transparency and > students’ satisfaction. After developing the study’s hypotheses, the researchers show the conceptual

framework in Fig. 1. RESEARCH METHODOLOGY PARADIGM, APPROACH, AND DESIGN This study follows a positivist paradigm because it uses objectively observable and measurable data and data analysis

techniques (Taylor and Medina, 2011). Unlike the qualitative approach, this study is quantitative as it uses numerical data analysed using statistical methods (Quick and Hall, 2015).

Further, an experimental survey design examines cause–effect relations based on data from many sample units (Tharenou et al. 2007; Cox and Battey, 2017). SAMPLING FRAME The study’s target

population is students pursuing Bachelor’s degree programmes from HLIs in Tanzania. The bachelor students are representative of tertiary education as it consists of also the former lower

tertiary students, who then joined for degree level. According to TCU statistics for 2023, the study population is 79,600 students. To obtain the sample, researchers used a clustering

approach with a multi-stage sampling method in selecting the HLIs and respondents’ samples. Three stages involved a selection of the coastal zone, Dar es Salaam city, and Ilala municipality

ending with 14 HLIs, each following criteria of the most significant number of HLIs. HLIs from the coastal zone sufficiently represent institutions countrywide due to most Dar es

Salaam-based institutions in other regions as branches or constituent colleges. At the final stage, the selected HLIs were contacted for the lists of registered students and systematically

selected 398 final-year students. The universities and colleges in the Eastern zone, particularly Dar es Salaam have constituent colleges and branches in different regions of the country,

giving an adequate level of representativeness of the study. The sample size for this study is 398 student respondents, using Yamane’s (1967) sample size formulation, with an error rate of

5%. DATA AND VARIABLES The study used primary, quantitative, and cross-sectional data that researchers collected with a structured questionnaire. The questionnaire measured the variables of

the study using seven-point Likert scale items. Service quality was measured using the extended SERVIQUAL Model with perceived transparency and trust. The appendix section describes a

preliminary study that resulted in the two new variables in the Model. Five items were used as indicators of perceived transparency (Park and Blenkinsopp, 2011), three items for trust

(Venkatesh et al. 2011; Medina and Ruffin, 2015), and eight items to measure satisfaction (Venkatesh et al. 2011). DATA VALIDITY AND RELIABILITY The researcher ensured data validity through

a questionnaire review by experts and a pilot survey of 30 respondents in one of the sampled HLIs. Further, Cronbach’s alpha coefficient was used to assess the questionnaire’s reliability by

scale reliability. This assesses how closely the scores for each item on a scale correlate and is validated using Cronbach’s alpha coefficient. A high Cronbach’s alpha score implies that

the items in the scale level were internally consistent if the scale was unidimensional (Chow, 2020). The researchers used Cronbach’s alpha test on all 40 questionnaire items in this study.

The computed reliability score is greater than the threshold value of 0.6, implying the items in the scale level were internally consistent (Fornell and Larcker, 1981). DATA ANALYSIS The

structural relationship between variables was measured using Partial Least Squares-Structural Equation Modelling (PLS-SEM) processes. Under the PLS-SEM process, researchers developed two

assessment models (the outer and inner models). The outer Model is a measurement model that predicts the correlation between indicators or parameters estimated with their latent variables.

Measurement model evaluation seeks to ensure the validity and reliability of the concept measures, supporting the merit of including them in the path model (Hair et al. 2022). After that, a

second model, the inner Model, is a structural model that predicts the causality relationship between latent variables. RESULTS From the deployed tools, the researcher returned all 398

filled questionnaires fit for statistical analysis, 100% response rate. Of these responses, 242 (or 61%) were males, and 156 (or 39%) were females. Male dominance explains the still-existing

gender gap in access to tertiary education (Tuomi et al. 2015). Most respondents (87%) were between 18 and 24, and the minority were above 24 because this is a relevant age range for most

college students. EVALUATION OF MEASUREMENT MODEL (OUTER MODEL) The value of the factor loadings indicator, which measured the construct, was used to assess the reliability test for the

indicators in the PLS. An indicator is considered valid if the factor loading value exceeds 0.707 (Risher and Hair, 2017). The researcher eliminated three items because their factor loadings

were <0.7: ‘Tangibility1’, ‘Reliability1’, and ‘Reliability2’. Table II shows that all the remaining items used to measure the constructs had a value >0.706. The average variance

extracted (AVE) determines convergence validity. Researchers propose that AVE values should be >0.5. The current study’s researchers accept the constructs’ convergent validity within the

structural Model in this study (Table 2). As can be seen, all eight constructs vastly exceed the AVE condition, implying that the investigation has established convergent validity. The

researchers used a heterotrait-monotrait correlation ratio (HTMT) to establish discriminant validity, which is superior to the commonly used Fornell-Larker criterion and cross-loading

assessments (Ahrholdt et al. 2017; Henseler et al. 2015). According to the findings (Table 3), all the latent variable HTMT values are less than the conservative threshold of .90. EVALUATION

OF STRUCTURAL MODEL (INNER MODEL) After the estimated Model met the Outer Model criteria, the measurement was performed by testing the structural Model (Inner Model) and examining the value

of R-Square (R2) on the variable (Fig. 2). Table 4 displays the R-Square (R2) values on variables based on the measurement results. Based on the data in Table 4, the R Square value for the

Students’ Satisfaction variable was 0.569, and the R Square value for trust in an institution was 0.450. These figures of the coefficient of determination (R2) produced by the Model suggest

that 57% of the factors influencing students in Tanzanian HLIs to be satisfied could be accounted for by the study’s Model. Also, the perceived transparency could explain 45% (R2) of the

variance in trust in an institution. DIRECT EFFECT TEST RESULT The research used _t_-statistics (_t_-test) to test hypotheses at a significance level of 5%. If a _p_-value of <0.05 (α 5%)

was obtained in this test, it meant that the test was significant, and vice versa; if the p-value was more remarkable than >0.05 (α 5%), it told that the test was not significant. In

assessing the path coefficient given in Fig. 1 and Table V, the direct effect of test results for each variable could be seen in the SmartPLS algorithm Results Table. Table 5 shows that the

coefficient of the perceived transparency aspect is 0.671 as a result of testing the hypothesis, indicating that the transparency aspect positively affects trust in an institution. A study

found a significance value of _p_ with values 0.000 < 0.05 to be significant, implying that transparency positively and significantly affects trust in an institution. The reliability

aspect’s coefficient was known to be 0.155, indicating that the reliability aspect positively impacts student satisfaction. A significant value of _p_ with values 0.033 < 0.05 was

substantial, implying that reliability positively and significantly affects student satisfaction. The coefficient value of the trust in an institution aspect was 0.378, indicating that the

element of trust positively impacted students’ satisfaction and a significant value of _p_ with values 0.000 < 0.05. The coefficient values of the assurance, empathy, responsiveness, and

tangibility aspects had a _p_-value of >0.05 (α 5%), indicating that they had a negative effect on student satisfaction. The researchers concluded that these aspects negatively and

non-significant impacted student satisfaction. As a result, this study could not scientifically demonstrate that these factors were essential to student satisfaction. INDIRECT EFFECT TEST

RESULT The study used the _t_-statistics test (_t_-test), which had a significance level of 5%; if the test received a p-value of <0.05 (α 5%), it meant that the test was significant, and

vice versa if the p-value was more remarkable than >0.05 (α 5%), it meant that the test was not significant. The indirect test results of the analysed latent variables can be seen in

Table VI. The indirect relationship can be seen from the results obtained in Table 6 that the indirect relationship between perceived transparency and students’ satisfaction via trust in an

institution variable was 0.254; when the _p_-value is 0.000 < 0.005, then the trust variable indirectly and significantly affected the Students’ Satisfaction. In other words, there is an

indirect relationship between perceived transparency and student satisfaction through trust in an institution. MEDIATION TEST RESULT The study used SmartPLS 3.0 to run the mediation test

through bootstrapping steps. Hair et al. (2017) described the mediation test step-by-step. The researcher obtained the mediating test due to the "specific indirect effect." The

next step was to assess the level of mediation by examining the variance accounted for (VAF). VAF <20% is considered no mediation, VAF between 20 and 80% is partial mediation, and VAF

>80% is regarded as complete mediation. Table 7 depicts the mediation test. As a result, trust in the institution partially mediated the influence of perceived transparency on student

satisfaction. The bootstrapping result indicates (see Table 8) that the indirect effect of perceived transparency on students’ satisfaction through trust in an institution is statistically

significant at the confidence interval of 95%. DISCUSSION In accomplishing the first and second objectives, the researchers formed nine hypotheses for testing, which the study confirms in

Table 9. SUPPORTED HYPOTHESES The support of H2 (_β_ = 0.155, _p_ ≤ 0.05) shows students are satisfied with the reliability of the HLIs service provider in performing the promised service

dependably and accurately. This is explained by lecturers’ expertise in transferring knowledge to students and solving students’ concerns. In South Africa, reliability is the strongest

predictor of satisfaction through instructors’ expertise. In addition, reliability in terms of the lecturers’ punctuality in class teaching contributes to satisfaction. In Dodoma HLIs,

reliability was essential to student satisfaction (Magasi et al. 2022). Higher satisfaction of students in Zambia was influenced by the prompt sympathetic delivery of the promised service

(Mwiya et al. 2017). Empirically, the usefulness of expertise and punctuality in service provision as reliability measures in education service quality research are cemented. The study

results also support the relationship between transparency and trust by H6a (_β_ = 0.671, _p_ ≤ 0.05). Students trust their HLI if the institution is transparent in disseminating information

about the internship, student exchange, library resources, co-curriculum activities, counselling services, and handling student appeals and complaints. In Malaysia, bank transparency in

information dissemination leads to higher trust of customers (Jassem et al. 2021). Furthermore, in the context of customer experience, the relevance of the items within the factors produced

and the significantly higher factor loading values, ranging from 0.755 to 0.812, established sufficient validity. Also, the sharing procedures and private terms in the health sector made

patients feel more in control and less at risk (Esmaeilzadeh, 2019). Further, greater disclosure, accuracy, and clarity facilitated stakeholder trust in an organisation (Schnackenberg and

Tomlinson, 2016). A similar result was found by Medina and Rufin (2015), emphasising the relevance of the used perceived transparency measures for empirical research in education service

quality. The supported hypothesis H6b (_β_ = 0.378, _p_ ≤ 0.05) denotes that the student’s trust in the HLI’s service providers influences satisfaction. Students believe the services of the

HLI are socially responsible and always try to fulfil students’ expectations. The social responsibility of education services in Tanzanian HLIs is evidenced by the government’s support to

students through loan schemes (Moneva et al. (2020). Also, the student–lecturer mentorship programs such as academic advisors and career counselling (Masengeni, 2019) prove social

responsibility. The findings support those in Alzahrani et al. (2018); Saleem et al. (2017); and Medina and Rufin (2015) studies. The bootstrapping result indicates that trust significantly

mediates the relationship between perceived transparency and students’ satisfaction (H7, _β_ = 0.254, _p_ ≤ 0.05). The association has consistency with previous empirical findings where

trust was a significant mediator of service quality. In developing countries, trust strongly mediated the effect of service quality and customer perceived value on satisfaction with home

delivery service (Uzir et al. 2021). In Indian higher management education, trust mediated the relationship between staff competence, reputation, and competence on student satisfaction

(Singh and Jasial, 2021). Customers’ trust mediated banks’ Sharia non-compliance and customer commitment to Islamic banks in Pakistan (Usman et al. 2021). NOT SUPPORTED HYPOTHESES One of the

non-support hypotheses is H1, related to tangibility and satisfaction. The changing trend of quality perception about tangibility in the modern world explains this. The digital revolution

has shifted service value from tangibles to digital and online alternatives. In Saudi banks, customers did not consider tangibles an essential predictor of satisfaction because banks

upgraded the digital services more than the interiors of the branches (Albarq, 2013). In higher learning, for example, the presence of online repositories lowers the value of physical

libraries, and the presence of video lectures (i.e., youtube) degrades the importance of classroom facilities. Haming et al. (2019) found the same (no effect), while Sibai et al. (2021)

found a negative impact of tangibility. This evidences the declining role of tangibility as a service quality dimension in services with high growth of ICT use. The H3 is not supported as

the HLI students do not share consistent behaviour towards the responsiveness of the institution’s service providers. The result follows from the absence of frontline staff always available

to respond to student queries. This is due to the nature of the HLI, where the lecturer’s availability is limited to a few consultation hours, and the available administrative staff has

limited service in academic matters. This result in the education sector is contrary to the case of the Iraq hospitality industry because hotels always have a frontline team to care for

guests. While Hamming et al. (2019) found responsiveness to affect satisfaction, Sibai et al. (2021) found no effect. This contradiction calls for further research on determinants of the

impact of responsiveness on satisfaction. The study results do not support the hypothesis regarding the effect of assurance. Referring to it as a service provider’s capacity to guarantee

safety and promise of service to win customers’ confidence (Haron et al. 2020), many findings contradict this study’s findings. Despite the teaching excellence, higher learning emphasis by

the institutions ends at and is evaluated using students’ examination performance, lowering their assurance of acquired education beyond examinations. In banking, the safety and confidence

of customers explained their satisfaction (Haron et al. 2020), and the same case was found in hotels (Ali et al. 2021) and health (Mashenene, 2019). In Yılmaz and Temizkan (2022), assurance

affected satisfaction because students attached importance to the international prestige of their colleges in Turkey. This is not the case for Tanzania, a developing country where

comparably, students’ international reputation in their institutions is lower. The effect of assurance was also found by Umoke (2020), Koay et al. (2022), and Magasi et al. (2022). Empathy

is not a significant variable, meaning that H5 is not supported because, in higher learning education, lecturers’/institutions’ empathy to customers (students) is limited and governed by

rules and principles that demand more customer responsibility to the service provider than the opposite. For example, students’ well-being depends on their class attendance, finishing

assignments on time, and achieving minimum passes in examinations; empathy cannot affect these requirements. The situation is evident in a study by Mashenene (2019), which supports this

assertion. Although perceived transparency indirectly affects satisfaction through trust (H7), it is not significantly related to satisfaction directly (H6). The support of H6a shows

students develop trust when they feel their HLIs are transparent in disseminating information. The support of H7 shows the mediation effect generated by the trust is significant. In other

words, institutions can only develop trust after the students have experienced the transparency of service. As a result, if a group of respondents has not used an internship or student

exchange service, they may be unable to evaluate the service’s transparency from service providers. The explanations explain why H6 is not supported. The finding is consistent with

Porumbescu (2017), who found negative transparency concerning citizens’ satisfaction with public service provision because of information asymmetry. CONCLUSIONS While education service

quality matters more, Tanzania’s educational policy reforms focus on enrollment growth (Amutabi, 2021). As a result, infrastructural developments (Mwapachu, 2010) and student financial

support (Nahende, 2013) programmes are implemented, while reports show student dissatisfaction with education services persists (TCU, 2019). The dissatisfaction suggests, among other things,

flaws in the pre-existing measurement models of service quality in Tanzanian higher education. Through a modified SERVIQUAL framework adopted by the study, evidence is clear that

reliability is a significant predictor of student satisfaction. The implications for practice and public policy are profound. Promoting lecturers’ expertise in transferring knowledge and of

all staff in solving students’ issues professionally, especially with punctuality, are effective strategies to raise students’ satisfaction with education service. The evidence further

suggests that transparency significantly affects students’ satisfaction through trust mediation. This implies that the Ministry of Education and HLIs must promote openness with which the

institutions and employees disseminate information as they serve their customers (students). Particularly, HLIs need to improve transparency in sharing information about internship

opportunities, student exchange programmes, co-curriculum activities, counselling services, and handling student complaints. The mediation effect of trust calls for higher education

stakeholders to improve the social responsibility of their service and fulfil students’ expectations of the service. Theoretically, the study contributes to reconstructing the transparency

and trust-based service quality–satisfaction model to explain student satisfaction in Tanzanian higher learning institutions. Future research can test the application of the

transparency–trust-based service quality model in other sectors facing service quality problems, particularly public health and utilities. Secondly, while satisfaction is an important goal,

much more is students’ knowledge gained in the education given, measured by academic performance. Future studies should consider extending the Model by examining how students’ satisfaction

effects compare to academic performance effects. Thirdly, the non-support of service quality dimensions incorporated in the SERVQUAL Model and supported in other studies deserves close

attention. It is crucial to determine which group of students is significantly impacted by particular service quality dimensions to realise the government’s goal of encouraging more people

to seek tertiary education and to support the sustainability of the local HLIs. For example, suppose the empathy dimension is an essential criterion of interest to the HLIs in developing a

niche marketing and operating strategy. In that case, it is helpful for future researchers to explore the sub-dimensions that can explain empathy. This current study looked into how service

quality affects satisfaction, but student satisfaction is not the end goal of education. Using the DeLone and McLean model, future research can examine how satisfaction mediates the quality

of the learning process and academic performance. DATA AVAILABILITY The raw data used for this study is available upon request. REFERENCES * Ahrholdt DC, Gudergan SP, Ringle CM (2017)

Enhancing service loyalty: The roles of delight, satisfaction, and service quality. J Travel Res 56(4):436–450. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287516649058 Article Google Scholar * Akman E,

Kopuz K (2020) Sağlık hizmetlerinde kalite algısı: SERVQUAL model incelemesi. Ordu Üniversitesi Sosyal Bilimler Enstitüsü Sosyal Bilimler Araştırmaları Dergisi 10(3):866–880 Google Scholar

* Albarq AN (2013) Applying a SERVQUAL model to measure the impact of service quality on customer loyalty among local Saudi banks in Riyadh. Am J Ind Bus Manag 3(08):700.

https://doi.org/10.4236/ajibm.2013.38079 Article Google Scholar * Ali BJ, Gardi B, Jabbar OB, Ali AS, Burhan IN, Abdalla HP, Aziz HM, Sabir BY, Anwar G (2021) Hotel service quality: the

impact of service quality on customer satisfaction in hospitality. Int J Eng Bus Manag 5(3):14–28. https://doi.org/10.22161/ijebm.5.3 Article Google Scholar * Ali F, Hussain K, Konar R,

Jeon HM (2017) The effect of technical and functional quality on guests’ perceived hotel service quality and satisfaction: A SEM-PLS analysis. J Qual Assur Hosp Tour 18(3):354–378.

https://doi.org/10.1080/1528008X.2016.1230037 Article Google Scholar * Ali M, Raza S (2017) Service quality perception and customer satisfaction in Islamic banks of Pakistan: the modified

SERVQUAL Model. Total Qual Manag Bus Excell 28(5–6):559–577. https://doi.org/10.1080/14783363.2015.1100517 Article Google Scholar * Alzahrani L, Al-Karaghouli W, Weerakkody V (2018)

Investigating the impact of citizens’ trust toward the successful adoption of e-government: a multigroup analysis of gender, age, and internet experience. Inf Syst Manag 35(2):124–146.

https://doi.org/10.1080/10580530.2018.1440730 Article Google Scholar * Amadeo K (2022) Are You Officially in the Labor Force? Labor Force and Its Impact on the Economy. Accessed on 12th

October 2022. The balance, newsletter. The Balance - Make Money Personal (thebalancemoney.com) * Amutabi M (2021) New Zeal in Africa’s Development. Int J Dev Sustain 10(9):117–132.

https://doi.org/10.14207/ejss.2021.v10n9p117 Article Google Scholar * Anantha RAA, Abdul GA (2012) Service quality and students’ satisfaction at higher learning institutions. a case study

of Malaysian University competitiveness. Int J Manag Strategy 3(5):1–16 Google Scholar * Arshad S, Khurram S (2020) Can the government’s presence on social media stimulate citizens’ online

political participation? Investigating the influence of transparency, trust, and responsiveness. Gov Inf Q 37(3):101486. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.giq.2020.101486 Article Google Scholar *

Capistrano EP (2020) Determining e-Government trust: an information systems success model approach to the Philippines’ government service insurance system (GSIS), the social security system

(SSS), and the bureau of internal revenue (BIR). Philippine Manag Rev 27:57–78 Google Scholar * Cheng X, Yan X, Bajwa DS (2017) Exploring the emerging research topics on information

technology-enabled collaboration for development. Inf Technol Dev 23(3):403–414. https://doi.org/10.1080/02681102.2017.1363070 Article Google Scholar * Chow LS (2020) Impact of Indian

Muslim Restaurants’ hygienic Atmosphere on Diners’ satisfaction: Extending the Expectation Disconfirmation Theory. (Doctoral dissertation, Universiti Tunku Abdul Rahman) * Cox DR, Battey HS

(2017) Large numbers of explanatory variables, a semi-descriptive analysis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 114(32):8592–8595. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1703764114 Article ADS MathSciNet CAS

PubMed PubMed Central MATH Google Scholar * Cronin JJ, Taylor SA (1992) Measuring service quality: a re-examination and extension. J Market 56:24–51 Article Google Scholar * Denhardt

RB, Denhardt JV (2009) Public administration: An action orientation. Wadsworth, Boston, MA Google Scholar * Eskildsen J, Kristensen K (2007) Customer Satisfaction – The Role of

Transparency. Total Quality Manag Bus Excell 18(1-2):39–47. https://doi.org/10.1080/14783360601043047 Article Google Scholar * Esmaeilzadeh P (2019) The impacts of the perceived

transparency of privacy policies and trust in providers for building trust in health information exchange: an empirical study. JMIR Med. Inf 7(4):140–150. https://doi.org/10.2196/14050

Article MathSciNet Google Scholar * Fornell C, Larcker DF (1981) Structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error: Algebra and statistics * Gracia DB, Arino LC

(2015) Rebuilding public trust in government administrations through e-government actions. Revista Española de Investigación de Marketing ESIC 19(1):1–11.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.reimke.2014.07.001 Article Google Scholar * Gronroos C (1990) Service Management and Marketing. Lexington Books, Lexington, MA Google Scholar * Grönroos C (1984)

A service quality model and its marketing implications. Eur J Market 18(4):36–44 Article Google Scholar * Hair JF, Hult GTM, Ringle CM, Sarstedt M (2017) A Primer on Partial Least Squares

Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM), 2nd ed. Sage Publications, Thousand Oaks MATH Google Scholar * Hair JF, Matthews LM, Matthews RL, Sarstedt M (2017) PLS-SEM or CB-SEM: Updated

guidelines on which method to use. Int J Multivariate Data Analysis 1(2):107–123 Article Google Scholar * Hair JF, Hult GTM, Ringle CM, Sarstedt M (2022) A Primer on Partial Least Squares

Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM)., 3rd Edn. Sage, Thousand Oakes, CA MATH Google Scholar * Haming M, Murdifin I, Syaiful AZ, Putra AHPK (2019) The application of SERVQUAL

distribution in measuring customer satisfaction of the retail company. J Distribution Sci 17(2):25–34. https://doi.org/10.15722/jds.17.02.201902.25 Article Google Scholar * Haron R, Subar

NA, Ibrahim, K (2020) Service quality of Islamic banks: satisfaction, loyalty and the mediating role of trust. Islamic Economic Studies. Publisher: Emerald Publishing Limited * Henseler J,

Ringle CM, Sarstedt M (2015) A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modelling. J Acad Market Sci 43(1):115–135.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-014-0403-8 Article Google Scholar * Hofmann YE, Strobel M (2020) Transparency goes a long way: information transparency and its effect on the professoriate’s

job satisfaction and turnover intentions. J Bus Econ 90(5):713–732. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11573-020-00984-0 Article Google Scholar * Honora A, Chih WH, Wang KY (2022) Managing social

media recovery: the critical role of service recovery transparency in retaining customers. J Retail Consum Serv 64:102814. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2021.102814 Article Google

Scholar * Hwang YS, Cho YK (2019) Higher education service quality, student satisfaction, institutional image, and behavioural intention. Soc Behav Pers 47(2):1–12.

https://doi.org/10.2224/sbp.7622 Article Google Scholar * Inan IE, Çelik E (2018) Perceived organizational trust and job satisfaction: an application in private and Public Banks of

Kastamonu Province. Al Farabi Int J Soc Sci 2(3):23–52 Google Scholar * Jassem S, Razzak MR, Sayari K (2021) The Impact of Perceived Transparency, Trust and Skepticism towards Banks on

adopting IFRS 9 in Malaysia. J Asian Finance, Econ Bus 8(9):53–66. https://doi.org/10.13106/jafeb.2021 Article Google Scholar * Johansson C, Lundborg AJ (2021) Financing higher education

in Tanzania: Exploring challenges and potential student loan models. (Master Thesis, Lund University). Publisher: Department of Design Sciences Faculty of Engineering LTH, Lund University,

Lund, Sweden Google Scholar * Kessy H (2020) Competence Based Education and E-Portfolio in Tertiary Education. GRIN Verlag * Kim S, Lee J (2012) E-participation, transparency, and trust in

local government. Public Adm Rev 72(6):819–828. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6210.2012.02593.x Article Google Scholar * Kim S, Lee J, Lee J (2018) Citizen participation and public trust

in local government: the Republic of Korea case. OECD J Budgeting 18(2):73–92. https://doi.org/10.1787/budget-18-5j8fz1kqp8d8 Article Google Scholar * Kisanga DH (2016) Determinants of

Teachers’ Attitudes Towards E-Learning in Tanzanian Higher Learning Institutions. The International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning, 17(5).

https://doi.org/10.19173/irrodl.v17i5.2720 * Koay KY, Cheah CW, Chang YX (2022) A model of online food delivery service quality, customer satisfaction and loyalty combine PLS-SEM and NCA

approaches. Br Food J. https://doi.org/10.1108/BFJ-10-2021-1169 * Kruss G, McGrath S, Petersen I, Gastrow M (2015) Higher education and economic development: the importance of building

technological capabilities. Int J Educ Dev 43:22–31. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijedudev.2015.04.011 Article Google Scholar * Kumar S, Murphy M, Talwar S, Kaur P, Dhir A (2021) What drives

brand love and purchase intentions toward the local food distribution system? A study of social media-based REKO (fair consumption) groups. J Retail Consum Serv 60:102444.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2021.102444 Article Google Scholar * Leisen Pollack B (2008) The nature of the service quality and satisfaction relationship: empirical evidence for

the existence of satisfiers and dissatisfiers. Manag Serv Qual Int J 18(6):537–558 Article Google Scholar * Li J, Qu J, Huang Q (2017) Why are some graduate entrepreneurs more innovative

than others? The effect of human capital, psychological factor and entrepreneurial rewards on entrepreneurial innovativeness. Entrep Reg Dev 30(5-6):479–501.

https://doi.org/10.1080/08985626.2017.1406540 Article Google Scholar * Magasi C, Mashenene RG, Dengenesa DM (2022) Service quality and students’ satisfaction in Tanzania’s higher

education: a re-examination of SERVQUAL model. Int Rev Manag Market 12(3):18–25 Google Scholar * Mansoor M (2021) An interaction effect of perceived government response on COVID-19 and

government agency’s use of ICT in building trust among citizens of Pakistan. Transform Gov: People Process Policy 15(4):693–707 Article Google Scholar * Manyaga T (2008) Standards to

assure quality in tertiary education: the case of Tanzania. Qual Assur Educ 16(2):164–180 Article Google Scholar * Masengeni M (2019) Building trust between academic advisers and students

in the academic advising centre at a private higher education institution. Educor Multidiscip J 3(1):159–172 Google Scholar * Mashenene RG (2019) Effect of service quality on students’

satisfaction in Tanzania Higher Education. J Bus Educ 2(2):1–8 Google Scholar * Mbise ER (2015) Students perceived service quality of business schools in Tanzania: a longitudinal study.

Quality Issues Insights 21st Century 4(1):28–44 Google Scholar * Mbise ER, Tuninga RSJ (2013) Applying SERVQUAL to business schools in an emerging market: the case of Tanzania. J Transnatl

Manag 18(2):101–124 Article Google Scholar * Medina C, Rufín R (2015) Transparency Policy and students’ satisfaction and trust. Transforming Government: People, Process and Policy * Mgaiwa

SJ (2018) The paradox of financing public higher education in Tanzania and the fate of quality education: the experience of selected universities. Sage Open 8(2):2158244018771729 Article

Google Scholar * Mgaiwa SJ (2018) Operationalizing quality assurance processes in Tanzanian higher education: academics’ perceptions from selected private universities. Creative Educ

09(06):901–918. https://doi.org/10.4236/ce.2018.96066 Article Google Scholar * Mgaiwa SJ (2021) Academics’ job satisfaction in Tanzania’s higher education: the role of the perceived work

environment. Soc Sci Hum Open 4(1):100143 Google Scholar * Mgaiwa SJ, Poncian J (2016) Public-private partnership in higher education provision in Tanzania: implications for access to

quality education. Bandung J Global South 3(6):1–21. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40728-016-0036-z Article Google Scholar * Moneva JC, Jakosalem CM, Malbas MH (2020) Students’ satisfaction in

their financial support and persistence in school. Int J Soc Sci Res 8(2):59. https://doi.org/10.5296/ijssr.v8i2.16784 Article Google Scholar * Mwapachu JV (2010) Challenges facing African

and Tanzanian Universities. Development 53(4):486–490. https://doi.org/10.1057/dev.2010.83 Article Google Scholar * Mwilongo KJ (2015) Reaching all through open and distance learning in

Tanzania. Int J Afr Asian Stud 7(0):24, https://iiste.org/Journals/index.php/JAAS/article/view/19573/19441 Google Scholar * Mwiya B, Bwalya J, Siachinji B, Sikombe S, Chanda H, Chawala M

(2017) Higher education quality and student satisfaction Nexus: Evidence from Zambia. Creative Educ 8:1044–1068. https://doi.org/10.4236/ce.2017.87076 Article Google Scholar * Mwongoso AJ,

Kazungu I, Kiwia RH (2015) Measuring service quality gap in higher education using SERVQUAL Model at Moshi University College of Cooperative and Business Studies (MUCCoBS). Implications for

improvement. Int J Econ Commerce Manag 3(6):298–317 Google Scholar * Naanwaab C, Diarrassouba M (2016) Economic freedom, human capital, and foreign direct investment. J Dev Areas

50(1):407–424. https://www.jstor.org/stable/24737356 Article Google Scholar * Nicholas N, Hartono KM, Vincent V, Gui A (2022) A Study on Student’s Satisfaction with E-learning Systems

During the COVID-19 Pandemic. In 2022 26th International Conference on Information Technology (IT) (pp. 1-4). IEEE * Njau FW (2019) An Integrated SERVQUAL Model and Gap Model in Evaluating

Customer Satisfaction in Budget Hotels in Nairobi City County. School of Hospitality and Tourism, Kenyatta University, Kenya. Nairobi, 10.35942/ijcab.v3iII.6 Book Google Scholar * Nyahende

VR (2013) The success of students’ loans in financing higher education in Tanzania. Higher Educ Stud 3(3):47–61. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ1080236 Article Google Scholar * Onditi OE,

Wenchuli TW (2017) Service quality and student satisfaction in higher education institutions: a literature review. Int J Sci Res Publications 7(7):328–335 Google Scholar * Parasuraman A,

Zeithaml VA, Berry L (1988) SERVQUAL: a multiple-item scale for measuring consumer perceptions of service quality. J Retailing 64(1):12–40 Google Scholar * Park H, Blenkinsopp J (2011) The

roles of transparency and trust in the relationship between corruption and citizen satisfaction. Int Rev Admin Sci 77(2):254–274 Article Google Scholar * Porumbescu GA (2017) Does

transparency improve citizens’ perceptions of government performance? Evidence from Seoul, South Korea. Adm Soc 49(3):443–468. https://doi.org/10.1177/0095399715593314 Article Google

Scholar * Quick J, Hall S (2015) Part Three: The Quantitative Approach. J Perioper Pract 25(10):192–196 PubMed Google Scholar * Ramírez Y, Tejada Á (2022) University stakeholders’

perceptions of the impact and benefits of, and barriers to, human resource information systems in Spanish universities. Int Rev Adm Sci 88(1):171–188.

https://doi.org/10.1177/0020852319890646 Article Google Scholar * Ramzi OI, Subbarayalu AV, Al-Kahtani NK, Kuwaiti AA, Alanzi TM, Alaskar A, Alameri NS (2022) Factors influencing service

quality performance of a Saudi higher education institution: public health program students’ perspectives. Inform Med Unlocked 28:1–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.imu.2021.100841 Article

Google Scholar * Raza SA, Umer A, Qureshi MA, Dahri AS (2020) Internet banking service quality, e-customer satisfaction and loyalty: the modified e-SERVQUAL model. TQM J 32(6):1443–1466.

https://doi.org/10.1108/TQM-02-2020-0019 Article Google Scholar * Risher J, Hair Jr JF (2017) The robustness of PLS across disciplines. Acad Bus J 1:47–55 Google Scholar * Saleem MA,

Zahra S, Yaseen A (2017) Impact of service quality and trust on repurchase intentions–the case of Pakistan airline industry. Asia Pacific J Mark Log 29(5):1136–1159.

https://doi.org/10.1108/APJML-10-2016-0192 Article Google Scholar * Saravanan R, Rao KSP (2007) Measurement of Service Quality from the Customer’s Perspective – An Empirical Study. Total

Quality Manag Bus Excell 18(4):435–449. https://doi.org/10.1080/14783360701231872 Article Google Scholar * Schnackenberg AK, Tomlinson EC (2016) Organisational transparency: a new

perspective on managing trust in organisation-stakeholder relationships. J Manag 42(7):1784–1810. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206314525202 Article Google Scholar * Sfenrianto S, Wijaya T,

Wang G (2018) Assessing the buyer trust and satisfaction factors in the E-marketplace. J Theor Appl Electron Commer Res 13(2):43–57. https://doi.org/10.4067/S0718-18762018000200105 Article

Google Scholar * Shin D (2020) User perceptions of algorithmic decisions in the personalised AI system: perceptual evaluation of fairness, accountability, transparency, and explainability.

J Broadcast Electron Media 64(4):541–565. https://doi.org/10.1080/08838151.2020.1843357 Article Google Scholar * Sibai MT, Bay Jr B, Dela RR (2021) Service Quality and Student Satisfaction

Using ServQual Model: A Study of a Private Medical College in Saudi Arabia. Int Educ Stud 14(6):51–58 Article Google Scholar * Singh S, Jasial SS (2021) Moderating effect of perceived

trust on service quality–student satisfaction relationship: evidence from Indian higher management education institutions. J Market Higher Educ 31(2):280–304 Article Google Scholar *

Solakis K, Peña-Vinces J, Lopez-Bonilla JM (2022) Value co-creation and perceived value: a customer perspective in the hospitality context. Eur Res Manag Bus Econ 28(1):100–175.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iedeen.2021.100175 Article Google Scholar * Sum NL, Jessop B (2012) Competitiveness, the knowledge-based economy and higher education. J Knowledge Econ

4(1):24–44. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13132-012-0121-8 Article Google Scholar * Tanzania Commission for Universities (2019) State of University Education in Tanzania. T.C.U, Dar es Salaam

Google Scholar * Tanzania Commission for Universities (2020) Rolling Strategic Plan 2020/21 – 2024/25 * Taylor PC, Medina, M (2011) Educational research paradigms: From positivism to

pluralism. - Murdoch University Research Repository. _Murdoch.edu.au_. [online] https://researchrepository.murdoch.edu.au/id/eprint/36978/ * Tharenou P, Donohue R, Cooper, B (2007)

Management Research Methods. https://doi.org/10.1017/cbo9780511810527 * Thelen PD, Formanchuk A (2022) Culture and internal communication in Chile: linking ethical organisational culture,

transparent communication, and employee advocacy. Public Relations Rev 48(1):102–137. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pubrev.2021.102137 Article Google Scholar * Thomas TD, Abts K, Stroeken K,

Weyden PV (2015) Measuring institutional trust: evidence from Guyana. J Politics Latin Am 7(3):85–115. https://doi.org/10.1177/1866802x1500700303 Article Google Scholar * Tossy T (2017)

Measuring the impacts of E-learning on students’ achievement in learning process: an experience from Tanzanian public Universities. Int J Eng Appl Computer Sci 02(02):39–46.

https://doi.org/10.24032/ijeacs/0202/01 Article Google Scholar * Trivedi SK, Yadav M (2020) Repurchase intentions in Y generation: mediation of trust and e-satisfaction. Marketing

Intelligence Planning 38(4):401–415. https://doi.org/10.1108/MIP-02-2019-0072 Article Google Scholar * Tuomi MT, Lehtomäki E, Matonya M (2015) As capable as other students: Tanzanian women

with disabilities in higher education. Int J Disability, Dev Educ 62(2):202–214. https://doi.org/10.1080/1034912x.2014.998178 Article Google Scholar * Umoke M, Umoke PCI, Nwimo IO,

Nwalieji CA, Onwe RN, Emmanuel IN, Samson OA (2020) Patients’ satisfaction with the quality of care in hospitals in Ebonyi State, Nigeria, using SERVQUAL theory. SAGE Open Med 8:1–9.

https://doi.org/10.1177/2050312120945129 Article Google Scholar * Usman M, Pitchay AA, Zahra M (2021) Non-Shariah Compliance of Islamic Banks and Customers Commitment: Trust as Mediator.

Adv Int J Bank Account Finance 3(8):28–36. https://doi.org/10.35631/AIJBAF.38003 Article Google Scholar * Uzir MUH, Al Halbusi H, Thurasamy R, Hock RLT, Aljaberi MA, Hasan N, Hamid M

(2021) The effects of service quality, perceived value and trust in-home delivery service personnel on customer satisfaction: evidence from a developing country. J Retail Consum Services

63:102–121. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2021.102721 Article Google Scholar * Vandewalle D (2018) Libya since independence. _Oil and state building_. Publisher: Cornell University

Press: https://doi.org/10.7591/978150173362 * Venkatesh V, Thong J, Chan F, Hu PH, Brown S (2011) Extending the two-stage information systems continuance model: incorporating UTAUT

predictors and the role of context. Inf Syst J 21:527–555. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2575.2011.00373.x Article Google Scholar * Wijaya E, Junaedi AT, Hocky A (2021) Service quality,

institutional image and satisfaction: can drivers student loyalty? Asia Pacific Manag Bus Appl 9(3):285–296 Google Scholar * Yamane T (1967) Statistics: An introductory analysis, 2nd edn.

Harper Row, New York MATH Google Scholar * Yılmaz K, Temizkan V (2022) The Effects of Educational Service Quality and Socio-Cultural Adaptation Difficulties on International Students’

Higher Education Satisfaction. 12(1), 1-18. https://doi.org/10.1177/21582440221078316 * Yuan X, Olfman L, Yi J (2020) How do institution-based trust and interpersonal trust affect

interdepartmental knowledge sharing? Information diffusion management and knowledge sharing: breakthroughs in research and practice, 424–449. https://doi.org/10.4018/978-1-7998-0417-8.ch021

* Zeithaml VA, Bolton RN, Deighton J, Keiningham TL, Lemon KN, Petersen JA (2006) Forward-looking focus: can firms have adaptive foresight? J Service Res 9(2):168–183.

https://doi.org/10.1177/1094670506293731 Article Google Scholar Download references ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The authors declare that this article has not been published previously, nor is it

being considered for publication elsewhere. AUTHOR INFORMATION AUTHORS AND AFFILIATIONS * Faculty of Business and Finance, Universiti Tunku Abdul Rahman, Perak, Malaysia Victor William

Bwachele, Yee-Lee Chong & Gengeswari Krishnapillai Authors * Victor William Bwachele View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Yee-Lee Chong

View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Gengeswari Krishnapillai View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google

Scholar CORRESPONDING AUTHOR Correspondence to Yee-Lee Chong. ETHICS DECLARATIONS COMPETING INTERESTS The authors declare no competing interests. ETHICAL APPROVAL The institution’s

Scientific and Ethical Review Committee (SERC) reviewed and approved the instruments and methodology. Ethical review and approval were required for the study on human participants per UTAR

institutional requirements. INFORMED CONSENT Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study. ADDITIONAL INFORMATION PUBLISHER’S NOTE Springer Nature

remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION ETHICAL APPROVAL FOR RESEARCH PROJECT/PROTOCOL

VOLUNTEER-CONSENT FORM DATA SUPPLEMENTARY FILE RIGHTS AND PERMISSIONS OPEN ACCESS This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use,

sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative

Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated

otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds

the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. Reprints and

permissions ABOUT THIS ARTICLE CITE THIS ARTICLE Bwachele, V.W., Chong, YL. & Krishnapillai, G. Perceived service quality and student satisfaction in higher learning institutions in

Tanzania. _Humanit Soc Sci Commun_ 10, 444 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-023-01913-6 Download citation * Received: 18 January 2023 * Accepted: 30 June 2023 * Published: 28 July 2023

* DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-023-01913-6 SHARE THIS ARTICLE Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content: Get shareable link Sorry, a shareable link

is not currently available for this article. Copy to clipboard Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative