The impact of network social presence on live streaming viewers’ social support willingness: a moderated mediation model

- Select a language for the TTS:

- UK English Female

- UK English Male

- US English Female

- US English Male

- Australian Female

- Australian Male

- Language selected: (auto detect) - EN

Play all audios:

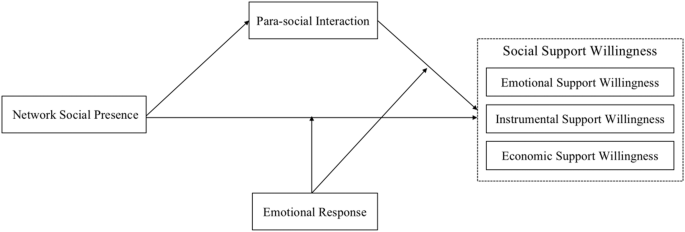

ABSTRACT With the accelerating development of social networks and the popularization of intelligent personal communication devices, live streaming has provided fluid experiences in time and

space for the Chinese people, especially during the COVID-19 pandemic. Live streaming has enabled the real-time communication and interaction between viewer and live host, and has created a

range of live hosts and new forms of business models due to the affordance of virtual currencies and gift reward mechanisms featured on live streaming platforms. Based on a questionnaire

survey of 515 live viewers, this study examines the impact of the viewers’ network social presence on social support willingness and analyzes the roles of parasocial interaction and

emotional response. The study reveals that network social presence has a direct positive impact on emotional, instrumental, and economic support willingness. Additionally, parasocial

interaction plays a mediating role in the impact of network social presence on emotional, instrumental, and economic support willingness. Furthermore, the higher the degree of emotional

response, the stronger the mediating effect of parasocial interaction on the relationship between network social presence and instrumental support willingness. Findings shed light on the

potential intermediate mechanism and the boundary conditions of the influence of network social presence on the social support willingness of viewers, providing new insights on promoting the

relationships between live hosts and viewers on live broadcast platforms. SIMILAR CONTENT BEING VIEWED BY OTHERS SOCIAL VIRTUAL REALITY HELPS TO REDUCE FEELINGS OF LONELINESS AND SOCIAL

ANXIETY DURING THE COVID-19 PANDEMIC Article Open access 07 November 2023 “INFLUENCING THE INFLUENCERS:” A FIELD EXPERIMENTAL APPROACH TO PROMOTING EFFECTIVE MENTAL HEALTH COMMUNICATION ON

TIKTOK Article Open access 11 March 2024 UNDERSTANDING THE PURCHASE INTENTION IN LIVE STREAMING FROM THE PERSPECTIVE OF SOCIAL IMAGE Article Open access 07 November 2024 INTRODUCTION The

rapid development of 5G mobile internet and personal intelligent terminal equipment significantly supports the adoption of live streaming platforms. Live streaming has become an important

component of China’s internet economy. According to CNNIC’s 50th “Statistical Report” (2022), the number of live streaming users in China reached 716 million by June 2022, accounting for

68.1% of the total number of internet users. Lu et al., (2018) demonstrate that live streaming in China has significant differences in content, style, and format when compared to live

streaming in North America and Europe. In contrast, live streaming in China is more widely used and integrates entertainment short video, goods-selling, online social networking, and

knowledge dissemination, which goes deeply into all aspects of social life and serves as the main channel for obtaining and transmitting information. As digital platforms for real-time

recording and uploading audio and video, live streaming platforms connect and construct viewers’ virtual presence experiences with the distant world, based on the characteristics of hyper

temporal and spatial attributes, para-authenticity, real-time interactivity, and connectivity (Cunningham et al., 2019; Lim et al., 2020), which significantly affects social media users’

interactions and willingness to convey information (Lin et al., 2014). Live streaming transmits images and sounds in real time through a variety of communication technologies, enabling the

viewer to interact in real time on the platform. In the live streaming system, the live host and the viewer can obtain a sense of participation through real-time interaction, providing a

unique immersive interactive experience that can trigger viewers’ behavioral intention. For example, the viewer can support their favorite host through monthly subscriptions or gift-giving

(Wongkitrungrueng et al., 2020). This kind of physical and situational experience can help to bridge the psychological gap between the live host and viewer, so as to promote the

establishment of a closer relationship between the viewer, the live host, and the platform (Liu et al., 2020), and enhance viewers’ social support willingness. Therefore, as a new media for

real-time broadcast and interaction, the impact of the unique immersive reality and real-time interactive social experience of webcasts on viewer behavior requires further study. A wealth of

existing work has explored the characteristics of live streaming from the perspective of regional, cultural, professional, and gender performance aspects, among others (Wohn, Freeman

(2020); Hsu et al., 2020). Studies also address live viewers, largely discussing the factors influencing viewer participation, based on technology adoption, user attitudes (Xu and Ye, 2020),

and user motivations (Hilvert-Bruce et al., 2018; Chen and Lin, 2018). However, current studies ignore the new phenomenon of live streaming, as characterized by “immersive” experiences, and

the real psychological state of the viewer in online interaction (Wongkitrungrueng et al., 2020). In fact, the interaction between the live host and viewer is a critical element of the live

platform. In this process, the viewers are regarded as “real people” who can perceive the existence of others and thus experience individual psychological feelings, such as intimacy and

psychological participation (Short et al., 1976), resulting in pseudo intimacy (Horton and Whol, 1956), which affects the viewers’ cognition and behavior, thus increasing the willingness of

social support for the live platform (Hassanein and Head, 2007). Therefore, network social presence is undoubtedly an appropriate perspective from which to study the viewer’s social support

willingness. We have discussed that, on live platforms, the viewer’s willingness to support the live host is affected by network social presence. Furthermore, in the live broadcasting field,

we need to reveal the practices of and mechanisms behind all parties’ actions, which work together to build emotional connections. Parasocial interaction is influenced by interaction

experience and network social presence; additionally, the viewer’s network social presence is an important prerequisite for parasocial interaction (Xiong, 2016). The sense of belonging,

immersion, and other aspects of network social presence generated by online interaction when watching live streaming reflects whether the viewer can have a sense of intimacy or direct

feeling in interpersonal interaction. Therefore, network social presence, as an individual’s intention to maintain relationships, can cultivate a large number of positive and loyal users,

and serves as an important factor for the construction of parasocial interaction. Above all, this study explores the impact of viewers’ network social presence on parasocial interaction and

social support willingness based on the live broadcast environment in China. The structure of the paper is as follows: the following section presents a literature review and our research

hypotheses. In “Research Design and Methods”, we propose a research model and further detail the research variables. In the “Data Analysis and Results” section, we report the sample and

verify the research hypothesis. The “Discussion and Conclusion” section explains the contribution, inspiration, and limitations of this work. LITERATURE REVIEW AND RESEARCH HYPOTHESIS SOCIAL

SUPPORT WILLINGNESS OF LIVE VIEWER The existing literature has defined and presented social support in numerous ways and from different angles. Early studies interpreted social support from

a functional perspective and claimed that social support is related to material, psychological, and spiritual support (Hoffman et al., 1988), which can convey care and love to the recipient

(Shumaker and Brownell, 1984), and make the recipient realize that they are part of an interpersonal network. Broadly, social support includes tangible support and intangible support.

Tangible support, also known as physical support, refers to a type of resource to enhance self-esteem and provide ways to meet material needs, such as instrumental assistance, goods, and

property. Intangible support refers to emotional care and the belief that support is available (Barrera, 1986). Furthermore, social support can be divided into offline social support and

online social support. Online social support mainly focuses on the potential and willingness to obtain information or emotional support through interpersonal relationships (Williams et al.,

2006), which is also known as social capital (Ellison et al., 2014). This study explores the social support willingness provided by live viewers to live hosts in online communities.

Therefore, the social support willingness in this study refers to willingness to provide rather than accept behavior, that is, one’s willingness to provide support at the information,

assistance, and emotional levels (Introne et al., 2016; Barak et al., 2008). Existing studies mostly focus on the willingness to provide informational support (Introne et al., 2016),

emotional support (Barak et al., 2008), and tangible social support (Lu et al., 2018). During live streaming, the viewer can interact with the live host or other viewers through messages, or

respond to the host’s questions and requests (Haimson and Tang, 2017).In addition to watching, the viewer on the live streaming platform can also express their support and appreciation for

the live host through likes, comments, and gifts (Haimson and Tang, 2017; Yu et al., 2018), and also provide immediate help at the live host’s request. Based on the above research, the

viewer’s willingness to provide social support is reflected in three aspects: instrumental, emotional and economic support willingness (Wohn et al., 2018). Instrumental support willingness

refers to the willingness of the viewer to provide direct assistance or practical action to the live host and help others by solving problems; emotional support willingness refers to the

viewer’s emotional willingness to comfort, encourage, or care for the live host; economic support willingness refers to the willingness of the viewer to provide rewards and other financial

support for the live host. Therefore, this study will conduct a more detailed investigation of the viewer’s willingness to provide social support from these three aspects: instrumental,

emotional and economic social support willingness. NETWORK SOCIAL PRESENCE AND SOCIAL SUPPORT WILLINGNESS Short et al., 1976 first proposed the term “social presence” and defined it as the

saliency of objects in media communication and the subsequent saliency of interpersonal relationships. However, there are now different perspectives and dimensions for the definition of

social presence. Initially, scholars explored social presence within the characteristics of media and revealed the communication effect of different media through comparing the differences

between remote communication media and face-to-face communication (Short et al., 1976). Some scholars began with a more psychological perspective and claimed that users’ perception of media

is more critical than the attributes of the media itself; these writers further defined social presence as the feeling of being with others in the media environment, including the degree of

trust in the process of interaction (Yeboah & Afrifa-Yamoah, 2023). The development of networks and the ontological subversion of virtual reality has promoted more in-depth and specific

discussions on the impact of social networks on individuals (Zhou et al., 2019). These studies focus on the extent to which individuals can perceive the existence of others in the process of

using social networks; the individuals’ psychological feelings, such as intimacy; and the individuals’ psychological involvement, forming the so-called “network social presence”. In other

words, network social presence is a sense of authenticity that individuals achieve through the social network, which makes individuals feel immersed in the the digital setting (Pettey et

al., 2010) and even enhances individuals’ willingness to take action on social network (Cheung et al., 2015). Some scholars have applied network social presence to online interactions and

marketing research. E-commerce studies have found that online shopping behaviors within social networks are highly similar to those within real-world settings. Some shopping websites and

brands stimulate consumer behavior by creating a network social presence and maintaining relationships with consumers (Algharabat, 2018). Jiang et al. (2022) affirm that social presence

affects the continued use and purchase intentions of Chinese consumers. Therefore, network social presence is an important factor driving individual consumption behavior intention. As

previously acknowledged, network social presence triggers a higher willingness to consume and promote the provision of more social support. Previous studies have shown that, in virtual

networks, network social presence can increase the stability and satisfaction of the relationship between the two parties, and then increase the willingness of users to use, consume, and

recommend products and services in the future (Choi et al., 2016; Chen et al., 2023), and improve the potential willingness of social support. Therefore, if the viewer is closely related to

the platform and has a high sense of network social presence, the viewer is more willing to provide more social support to the platform and hosts. Based on the above analysis, network social

presence plays an important role in the willingness of social support. Consequently, the hypotheses are developed as follows. H1. Network social presence has a positive impact on the

viewer’s willingness to support the host (a: emotional support willingness; b: instrumental support willingness; c: economic support willingness). MEDIATION: PARASOCIAL INTERACTION

Parasocial interaction was first proposed by Horton and Whol, 1956 who defined parasocial interaction as a “simulacrum of conversational give and take.” Horton and Strauss (1957) further

indicated that parasocial interaction is a solely one-sided experience of the audience; most examples of this type of experience are based on the audience’s own illusion. Rubin and McHugh

(1987) echoed this finding, describing parasocial interaction as a one-way interpersonal relationship between media performers and their TV audiences. Currently, parasocial interaction has

been introduced into live streaming contexts, emphasizing the “illusion” and unilateral intimacy between the viewer and live host (Chen et al., 2021; Sheng et al., 2022). Furthermore,

parasocial interactions can influence viewers’ emotional responses, attitudes, and behaviors (Chang and Kim, 2022; Sheng et al., 2022), the center of attention in this study. The development

of the internet and social network has promoted increasing numbers of scholars to explore the impact of new media use on individual users from the perspective of network social presence

(Gao et al., 2017). In addition, investigations of network social presence highlight that the virtual space built through technology, similarly to real communication, can make media users

perceive strong sociality, authenticity, and intimacy, and produce a strong sense of belonging, reflecting the degree to which individuals use media to build interpersonal relationships.

Therefore, network social presence, as an important social psychological factor in the use of individual new media, has a far-reaching impact on interpersonal communication, which deserves

more attention. The network social presence can enhance the immersion and authenticity of group communication, improve the interactive experience between live hosts and strengthen the

network density, which can build a close connection between members, maintain the rapid flow of information and resources, and then generate a sense of identity with the group. In the live

streaming, the viewer and the host in the live room perceive each other’s existence, cause emotional reactions, and gradually build a parasocial relationship by continuously participating in

online discussions. Therefore, there is a positive relationship between network social presence and parasocial interaction. In line with the above, the following hypothesis was created. H2.

Network social presence has a positive effect on the parasocial interaction between the viewer and live host. Cohen (2004) believes that parasocial interaction is most suitable for

analyzing media figures who directly talk to the audience, such as newscasters and hosts. Rubin and Step (2000) found the parasocial interaction of radio hosts leads to changes in audience

attitudes and behaviors. In recent years, the vigorous development of social networks, especially the widespread use of live platforms, has narrowed the distance between media figures and

audiences, prompting new research on parasocial interaction. Lee and Watkins (2016) highlights the potential of social networks in establishing two-way communication and balancing the

relationship between media users and media properties. Stever and Lawson (2013) claim that YouTube, TikTok, and other social networking sites allow the audience to approach the personal life

of the media personality within the scope of the media personality, so as to obtain more social support. Furthermore, social media has expanded the phenomenon of parasocial interaction from

solely concerning the world of TV characters to becoming a real tool for marketing brands to consumers (Lee and Watkins, 2016). For example, Hsu et al. (2020) found that vloggers can deepen

viewers’ identity and sense of belonging and cultivate viewers’ fluid experience by establishing parasocial interaction, thereby urging viewers to purchase and enabling addiction.

Especially in the live streaming environment, parasocial interaction affects the social interaction between the live host and the viewer (Hu et al., 2017; Lim et al., 2020), and can promote

the impulsive consumption of the audience (Xiang et al., 2016). In view of the above discussion, we believe that parasocial interaction has a mediating effect between network social presence

and social support willingness. The existing studies provide a logical basis for investigating this mechanism. It is generally believed that the higher the viewer’s perception of network

social presence, the higher the frequency of interaction on the network, so the viewer is more likely to feel that they are in a “real” network society, which is also known as network

society presence. As for the impact of parasocial interaction on network social presence and social support willingness, studies have found that the degree of interactivity and vividness of

online advertising are regulated by the audience’s social presence, and influences their attitudes and behavioral intentions (Lu et al., 2016). In addition, according to the existing

research, network social presence can influence users’ satisfaction and sense of belonging, increase the possibility of contact, and strengthen the parasocial interaction between the

audience and the live host, so as to trigger more social support (Lin et al., 2014). Therefore, the interpersonal interaction in the live streaming environment should be included in the

influence of network social presence. According to the different degrees of network social presence, viewers with high network social presence are more suitable to perform tasks related to

interpersonal interaction. Above all, network social presence may not only directly affect the social support willingness of viewers but also indirectly affect the social support willingness

by enhancing the parasocial interaction. Therefore, we propose the following hypothesis: H3. Parasocial interaction plays a mediating role between network social presence and social support

willingness (a: emotional support willingness; b: instrumental support willingness; c: economic support willingness). MODERATION: EMOTIONAL RESPONSE There are different opinions regarding

whether different emotional experiences produce different physiological reactions. Every emotion is multi-dimensional; Mehrabian (1995) believed that an emotional response has three aspects:

pleasure, arousal, and dominance, namely, the PAD emotional-state model. Pleasure refers to the positive or negative performance of emotions such as happy, satisfied, and satisfied; arousal

refers to the level of individual physiological activation and alertness, on a scale of drowsiness to excitement; dominance is the state of individual control over situations or others.

This model is widely used in environmental psychology; although it is intended to represent the dimensions of emotional response rather than a complete typology of emotional responses

(Eroglu et al., 2003), its simple structure and widespread use make it an appropriate choice in this context. Russell (1979) believed that pleasure and arousal adequately capture the range

of appropriate emotional responses, and Eroglu et al., (2003) demonstrated that, when studying emotions in the network, pleasure and arousal are commonly used to present individual emotional

responses. Therefore, when exploring the emotional response of Chinese live cast viewers, this study only draws on the pleasure and arousal emotions in the PAD emotional state model, and

the dominance dimension is not included. As the core construct of emotional response, the degree of pleasure and arousal is generated on the basis of cognition, which in turn affects

cognition. They are the internal factors that regulate and control cognition, so as to achieve different psychological dynamic response (Pan and Huang, 2017). Multiple studies have explored

how emotional constructs interact with and influence user attitudes and behaviors, confirming that individual behavior is regulated by positive emotions (Gavriel-Fried and Ronen, 2016). In

the context of webcasts, the viewer’s social and psychological state is an important determinant of how viewers choose a live host to meet their needs; that is, the viewer can be aware of

their needs, consider various channels and content, evaluate the choice of functionality, and choose the media that they believe can provide the satisfaction they seek. In this framework,

parasocial interaction is considered to meet the emotional needs of the viewer and can reduce anxiety (Suggs & Guthrie, 2017). If the live host can provide positive emotions for the

viewer and activate individual energy, viewers will have high satisfaction with the live host, which is the main reason for viewers to form parasocial interaction and provide social support.

Specifically, a parasocial interaction relationship is formed between the live viewer and the live host, which conveys valence and arousal to the viewer, thus making the viewer more

inclined to provide social support. At the same time, the financial media environment enabled by new technology promotes highly autonomous participation mechanisms, and the emotional

perception of the webcast platform also promotes the continuous use and recommendation willingness of viewers (Han et al., 2015). Therefore, under the influence of different degrees of

valence and arousal, the influence of the parasocial interaction perception on viewer’s social support willingness is also accordingly different. Specifically, in the case of high positive

emotional response, the impact of parasocial interaction on social support intention increases. However, in the situation of low positive emotional response, the incremental impact of

parasocial interaction on social support decreases. Based on the above analysis, we hypothesize the following: H4. Emotional response amplifies parasocial interaction’s effect on social

support willingness (a: emotional support willingness; b: instrumental support willingness; c: economic support willingness). Due to the experiential communicability and flexibility (Dale

and Pymm, 2009) of live streaming, viewers feel a sense of belonging and pleasure when watching the live content. In this process, the relationship between viewer and the media has become

closer and has broken through the constraints of time and space, which can guide the viewer’s online social presence and trigger an obvious positive emotional response. Furthermore, emotion,

as one of the factors affecting user behavior (Gavriel-Fried and Ronen, 2016), is guided by a positive relationship between viewer and host that urges both parties to work together to

better meet each other’s needs. Previous studies have shown that emotional response can not only affect audience satisfaction but also adjust audience’s willingness to support (Cheikh-Ammar

and Barki, 2016). As a high level of network social presence can arouse the viewer’s positive emotional response, the viewer may therefore maintain a long-term good relationship with the

host and provide social support. Hence, we hypothesize the following: H5. Emotional response has a moderation role in the process of the effect of network social presence on social support

willingness (a: emotional support willingness; b: instrumental support willingness; c: economic support willingness). According to the above theoretical basis and research assumptions, this

study proposes the following research model, as shown in Fig. 1. METHODOLOGY SAMPLE AND DATA COLLECTION This study takes users who are over 18 years old and have watched the live as the

research sample. The data for the study was collected through a snowball sampling procedure. Because of the unavailability of a valid sample frame and the difficulty of conducting random

sampling for all live streaming viewers, this study used a non-probability sampling approach. The snowballing sampling is simple, inexpensive, and usable, and it is also helpful in

determining the relationships between various events and situations (Sahu et al., 2021). Further, due to the snowball effect of participant referrals, a higher number of responses were

obtained. Previous studies confirm that the snowballing sampling method is effective and appropriate for multivariate data processing and estimating the results (Almaqtari et al., 2023; Sahu

et al., 2021; Chan, 2020; Noy, 2008; Wright and Stein, 2004). We designed the questionnaire on QuestionnaireStar (https://www.wjx.cn/; a professional data collection website in China).

Respondents can access our questionnaire homepage through an online link. The primary researcher used personal communication with “seeds” to assist the data collection process. The

questionnaire survey started on June 9, 2022 and ended on June 24, 2022. They sent the questionnaire to respondents via social medias and asked respondents to send it to another potential

participant after completing the survey. Respondents’ participation was completely consensual, anonymous, and voluntary. Moreover, the questionnaire does not cover the highly sensitive

personal identity information such as the name, home address, telephone number, ID number of the respondents, ensuring the confidentiality and anonymity. The data obtained in this survey is

only for academic research purposes. In addition, all procedures performed in studies involving human participants followed the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national

research committee and with the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. To obtain valid samples, we created two screening questions: “Are you

over 18 years old” and “Have you watched live streaming before?” If one of the respondent’s answers is “no,” the participant is directed to the end of the survey. After excluding the samples

who are under the age of 18, had not watched the live streaming, and expressed an abnormal response time, 515 valid samples remained, and the sample pass rate was roughly 83.5%. Hair et

al., (2006) mentioned that the factor analysis requires a minimum sample size of at least five times the number of measurement items in the study. This present study has 25 measurement items

adapted from previous literature, thus, the appropriate number of sample size would be at least 125 respondents. Thus, the current sample size of 515 participants was suitable for

conducting the research. Therefore, 515 surveys were considered the final sample for the present study. As the Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin measure of sampling adequacy value is 0.954, it is greater

than 0.7, this sample is considered statistically adequate for estimating the results. Furthermore, this test shows high significance at the 1% level (_p_-value = 0.000, <0.01),

indicating the suitability and adequacy of the sample. DEMOGRAPHIC INFORMATION OF THE SAMPLE To increase the generalizability of the findings, respondents with diverse backgrounds (age,

gender, education, residence, etc.) were selected (as per Mladenović et al., 2020). As shown in Table 1, 227 respondents (44.08%) were male. Most respondents were between 18 and 39 years old

(78.84%). In terms of education level, the number of respondents with a bachelor’s degree was the largest, 256 (49.71%); followed by below a bachelor’s degree, 186 (36.12%); and then a

master’s degree or above, 73 (14.17%). Most of the respondents watched live streaming platforms for an average of 2.6 days a week: 196 samples (38.06%) watched live streaming platforms for

less than one day, 199 samples (38.64%) for 1–3 days, and 120 samples (23.3%) for more than three days. 390 samples (75.7%) spent an average time per viewing of less than one hour, 94

samples (18.25%) less than one hour, and 31 samples (6.02%) more than two hours. According to the 2021 Research Report on the Development of China’s Online Live Broadcasting Industry, in

2021, 74.4% of China’s online live broadcasting users were 39 years old or younger: 47.1% of users were male, 52.9% were female users, 78.1% watched each live broadcast for less than one

hour, and 17.2% watched for one to two hours (iiMediaResearch (2022)). Therefore, the basic characteristics of the sample in this study are broadly consistent with the current composition of

China’s network live streaming users, indicating that the sample is representative. VARIABLE MEASUREMENT To increase the validity and reliability of the results, each construct in the model

has multiple items adapted from previous studies with minor changes to fit the research context. All the questionnaire information was translated from English to Chinese with manual testing

to optimize wording and grammar to ensure the linguistic accuracy and comprehensibility of the questionnaire. This study used a seven-point Likert scale to measure survey items, where one

indicates strongly disagree/inconsistent and seven indicates strongly agree/consistent. NETWORK SOCIAL PRESENCE The measurements of network social presence were adopted from studies by

Hassanein and Head (2007), Lu et al., (2016), and Gao et al., (2017). Some scale items were deleted per the CFA, leaving eight items. Respondents were asked to rate how they felt about the

following statements; a seven-point Likert-type scale (one denoting “strongly disagree” and seven denoting “strongly agree”) was utilized for the following eight statements: (1) “in the live

studio, I will pay close attention to the existence of others”; (2) “I felt someone approaching me in the live studio”; (3) “in the live studio, I have a sense of reality of face-to-face

communication with others”; (4) “in the live studio, I have a feeling of social interaction”; (5) “in the live studio, I have a warm feeling”; (6) “in the live studio, I feel close to

others”; (7) “in the live studio, the knowledge shared by the live host can benefit me”; (8) “in the live studio, I have a high degree of recognition for the behavior and view of the live

host.” An overall network social presence composite measure was created by averaging the seven items together, Cronbach’s α = 0.888, _M_ = 3.434, _SD_ = 1.035. PARASOCIAL INTERACTION Because

the initial parasocial interaction scale was created considering television news announcers (Rubin et al., 1985), some measurement items are not suitable for online live streaming (for

example, “I miss seeing my favorite newscaster when he or she is on vacation”) or present a specific program format or content (for example, “When the newscasters joke around with one

another it makes the news easier to watch”); these items were excluded. To measure the quasi-social interaction of research objects, previous research adapted the initial 20 measurement

items from Rubin, Perse, and Powell, (1985) and reduced them to several measurement items, as found in studies by Choi et al., (2019), Kim and Song, (2016). Reducing the number of

measurement items is suggested for addressing response behavior and data quality problems (Cheah et al., 2018; Drolet and Morrison, 2001), especially for participants from the general public

(Messer et al., 2012). This study selected five current measurement items based on the characteristics of online live streaming, and these five measurement items showed strong reliability

in this study (Cronbach’s α = 0.913), indicating that the internal consistency of these five measurement items is highly suitable for measuring quasi-social interaction. The five items are

as follows: (1) “I look forward to watching the live broadcast on her/his live channel”; (2) “Watching the live stream makes me feel that the live host is accompanying me”; (3) “I think the

live host is like my friend”; (4) “I will pay attention to the news of my favorite live host”; (5) “When I watch the live stream, I feel like I am a member of their live team.” A seven-point

Likert-type scale (1 denoting “strongly disagree” and 7 denoting “strongly agree”) was used for all items. To create a composite measure of parasocial interaction, the five items were

averaged together, _M_ = 3.529, _SD_ = 1.224. EMOTIONAL RESPONSE The measurements of emotional response were derived from studies by Mehrabian (1995) and Jin et al., (2020). The PAD

emotional-state model is widely applied in environmental psychology, although it is intended to represent the dimensions of emotional response rather than a complete typology of emotional

responses (Eroglu et al., 2003). However, its simple structure and widespread use make it a suitable choice in this context. Initially, we designed three items to measure pleasure and

arousal, but some scale items were deleted per the confirmatory factor analysis (for example, “Live streaming content makes me interested”, “Watching live streaming makes me happy”, and

“Watching live streaming makes me feel stimulated”). A total of three measurement items remained, and these three measurement items showed strong reliability in this study (Cronbach’s α =

0.813), indicating that the internal consistency of these three measurement items is highly suitable for measuring emotional response. The five items are as follows: (1) “I enjoy myself in

the live studio”; (2) “The live streaming content makes me feel novel and fresh”; (3) “Watching the live stream can make my life and work full of power.” A seven-point Likert-type scale (one

denoting “strongly inconsistent” and seven denoting “strongly consistent”) was used for all items. In this study, three items were summed and averaged to establish a comprehensive index of

emotional response, _M_ = 3.797, _SD_ = 1 .104. SOCIAL SUPPORT WILLINGNESS The measurements of emotional support willingness, instrumental support willingness, and economic support

willingness were adopted from Wohn et al., 2018 study. A seven-point Likert-type scale (one denoting “strongly disagree” and seven denoting “strongly agree”) was used for all items. Among

them, emotional support willingness includes three items: (1) “I am willing to send some encouraging words on the bullet screen to show my support for the live host”; (2) “I am willing to

try to interact with the live host to make them feel concerned”; (3) “I am willing to express my support for the live host in some way.” This study sums the three items and averages them to

construct the index of emotional support willingness (Cronbach’s α = 0.898, _M_ = 3.790, _SD_ = 1.360). Instrumental support willingness includes three items: (1) “If the live host really

needs it sometimes, I am willing to try to help him/her”; (2) “If the live host needs to complete a time-limited task, I am willing to help him/her”; (3) “If there is a problem in the live

studio, I am willing to help the live host solve it.” This study sums the three items and averages them to construct an indicator of instrumental support willingness (Cronbach’s α = 0.917,

_M_ = 3.548, _SD_ = 1.328). Economic support willingness includes three items: (1) “I am willing to reward the live host by giving virtual currency and help him/her make a living”; (2) “I

would like to reward the live host to express my gratitude by giving virtual currency”; (3) “I am willing to reward the live host and support his/her efforts by giving virtual currency.”

This study sums the three items and averages them to construct the index of economic support willingness (Cronbach’s α = 0.931, _M_ = 2.862, _SD_ = 1.423). RESULTS ANALYSIS OF VARIABLE

CORRELATION Table 2 shows the correlation between the six variables. There is a positive correlation between network social presence and emotional support willingness (_r_ = 0.597, _p_ <

0.01), instrumental support willingness (_r_ = 0.602, _p_ < 0.01), economic support willingness (_r_ = 0.518, _p_ < 0.01), and parasocial interaction (_r_ = 0.703, _p_ < 0.01).

Parasocial interaction is also positively correlated with emotional support willingness (_r_ = 0.703, _p_ < 0.01), instrumental support willingness (_r_ = 0.700, _p_ < 0.01), and

economic support willingness (_r_ = 0.577, _p_ < 0.01). These findings provide preliminary data support for the subsequent hypothesis verification. RELIABILITY, VALIDITY, AND COMMON

METHOD BIAS In this study, the software Mplus 8.3 was used for confirmatory factor analysis to test the reliability and validity. According to Fornell, Larcker, (1981) and Hair et al.,

(2019), the AVE value of all variables being greater than 0.5 (Table 3) indicates that the six variables have good aggregate validity. The factor load of the item corresponding to each

variable is greater than 0.5, and the square root of AVE is greater than the correlation coefficient between all variables (Table 2), indicating that the discriminant validity of each

variable is good. In addition, the combined reliability (CR) of all variables and Cronbach’s α were greater than 0.7, indicating that the internal consistency of the questionnaire is high

and each variable has good reliability. Therefore, the variables measured in this study are valid and credible. This study used a single data source for six variables, so it had the

possibility of common method bias (CMB). To ensure the accuracy of the research conclusion, we have taken several steps to solve the potential CMB. First, we used anonymous questionnaires to

improve the objectivity and freedom of respondents to answer questions. Second, we used different types of response scales (highly agree–highly disagree; very consistent–very inconsistent).

Third, we used the test of multicollinearity through the variance inflation factor (VIF) to check if CMB may be a threat (Kock, 2015). The VIFs were lower than 3.3, indicating that common

method variance in the data was not detected as CBM (Kock, 2015). HYPOTHESIS TESTING DIRECT EFFECT TEST H1 and H2 were verified by hierarchical regression analysis in SPSS 26.0 software

because linear models usually require normal distribution of dependent variables. However, the distribution of parasocial interaction (Kolmogorov-Smirnov _z_ = 0.180, _p_ < 0.001),

emotional support willingness (Kolmogorov-Smirnov _z_ = 0.185, _p_ < 0.001), instrumental support willingness (Kolmogorov-Smirnov _z_ = 0.198, _p_ < 0.001), and economic support

willingness (Kolmogorov-Smirnov _z_ = 0.169, _p_ < 0.001) significantly deviated from the normal distribution. Therefore, this study adopts the bootstrapping method to perform regression

analysis of 1000 samples under a 95% confidence interval. Bootstrapping is a nonparametric statistical method. Its basic principle is that when the assumption of normal distribution is not

tenable, a certain number of samples are resampled within the scope of the original sample data, and the parameters obtained by averaging each sampling are taken as the final estimation

results. The results of regression analysis (Table 4) show that network social presence has a significant effect on emotional support willingness (β = 0.787, _p_ < 0.001), instrumental

support willingness (β = 0.769, _p_ < 0.001), and economic support willingness (β = 0.708, _p_ < 0.001). That is to say, the stronger the network social presence, the more likely the

viewer will have social support for the live host. Therefore, H1a, H1b and H1c are supported. The results of the regression analysis also show that the network social presence can positively

influence the parasocial interaction (β = 0.831, _p_ < 0.001). This influence demonstrates that the enhancement of network social presence can strength parasocial interaction between the

live viewer and the live host. Therefore, H2 is supported. MEDIATING EFFECT OF PARASOCIAL INTERACTION SPSS PROCESS macro-Model 4 was applied to analyze the mediating effect of parasocial

interaction on the relationship between network social presence and emotional support willingness, instrumental support willingness, and economic support willingness. The mediating effect

model results (Table 5) show that the parasocial interaction of live viewers regarding the network social presence and emotional support willingness (β = 0.510, 95% CI [0.405, 0.612]),

instrumental support willingness (β = 0.487, 95% CI [0.388, 0.594]), and economic support willingness (β = 0.408, 95% CI [0.288, 0.531]) played a significant positive mediating role.

Therefore, H3a, H3b, H3c are supported. MODERATING EFFECT OF EMOTIONAL RESPONSE Through the model 15 in PROCESS V4.0 of SPSS 26.0, this study continues to test whether the moderating effect

of emotional response is tenable under the mediation effect of parasocial interaction. We performed a bootstrap test by taking the score of the average emotional response with plus or minus

one unit of standard deviation. The results show that (Table 6) the parasocial interaction and emotional response has a significant predictive effect on the instrumental support willingness

(β = 0.096, _t_ = 2.142, _p_ < 0.05). Therefore, emotional response plays a significant positive moderating role in “network social presence-parasocial interaction-instrumental support

willingness”. Table 7 shows that the mediating effect of parasocial interaction is significant at three levels of emotional response. Specifically, when the level of emotional response is

low (less than 1 standard deviation), the mediating effect of parasocial interaction is supported (β = 0.346, 95% CI [0.195, 0.503], excluding 0). The mediating effect of parasocial

interaction is supported when the emotional response is averaged (β = 0.434, 95% CI [0.315, 0.553], excluding 0) and higher than 1 standard deviation (β = 0.522, 95% CI [0.376, 0.653],

excluding 0). Moreover, the mediating effect of parasocial interaction increases significantly with the improvement of emotional response. That is to say, the mediating effect of parasocial

interaction is the strongest when emotional response is high (β = 0.522). In summary, the network social presence indirectly affects the instrumental support willingness of the live viewers

by influencing the parasocial interaction. The strength of this indirect effect depends on the level of emotional response. The higher the emotional response, the stronger the mediation

effect of parasocial interaction. However, other moderating effects of emotional response were not significant. Therefore, H5a is verified and H5b and H5c are not supported. DISCUSSION This

paper examines the impact of network social presence, parasocial interaction, and emotional response on livestream viewers’ social support willingness, as well as the interaction mechanisms

between these influencing factors. Through 515 valid samples, we have supported some previous research conclusions but also creatively proposed some research arguments, inspected and tested

them, and finally constructed a possible pathway that affects the willingness of live viewers to provide social support to the live host. The specific research conclusions are as follows.

This study found that network social presence can positively promote the willingness of live viewers to support the host at three levels of social support. These findings suggest that

network social presence is an important factor in explaining social support willingness in live streaming environments. The findings show that the network social presence can give the viewer

a real experience in the media intermediary environment, not only allowing viewers to have a positive attitude towards the media, improving the pleasure of media viewing, but also enhancing

the persuasive effect of media information (Westerman et al., 2015). Previous research has also confirmed the importance of network social presence in intermediary environments (Cummings

and Wertz, 2022). The findings support the proposition that network social presence positively impacts the economic support willingness of live viewers, and this is consistent with previous

studies, which suggests that shaping viewers’ network social presence is an effective strategy for live streaming platforms to maintain their cooperation with the viewers and subsequently

trigger more purchasing addiction (Huang et al., 2022; Algharabat, 2018). However, apart from the economic support willingness, limited research has explored the effect of network social

presence and other forms of support willingness. Therefore, this study further investigated the relationship between network social presence and emotional and instrumental support

willingness, and found that network social presence also had a positive predictive effect on emotional and instrumental support willingness in the live streaming environment. Compared to

traditional media, live streaming platforms have the advantage of being three-dimensional, interactive, and real-time, allowing viewers to observe the host’s facial expressions, body

gestures, and their offices (or homes) while watching live streaming, and to hear their voices in real time. These rich sensory stimuli make online conversations similar to face-to-face

interactions (Zhang et al., (2022)), generating a sense of identity and companionship with the host, as well as the sense of coexistence and connection, immersing viewers in a virtual

interaction. This sense of social presence in the virtual space as a factor helping the development of close social bonds (Maloney and Freeman, 2020) has a positive impact on the viewer’s

social support willingness. This research conclusion expands upon and enriches the research and application aspects of this relationship. Moreover, network social presence was found to have

a significant and direct impact on parasocial interaction. This is consistent with previous research results (Kim and Song, 2016; Lee, 2013). These findings resonate well with the notion

that social presence can affect the formation of PSI (Lombard and Ditton, 1997). As the media form evolves in the direction of “humanization” proposed by Levinson, the necessity of “personal

participation” in social activities decreases with the evolution of media (Meyrowitz, 1986). Live streaming not only enables the live host to release information in the form of text and

pictures but also through voice and video that can convey richer social clues over a variety of communication technologies. High network social presence communication that uses humor,

emojis, and phatic communication to express interconnectedness with viewers can foster a sense of intimacy, which is part of the parasocial interaction experience (Rubin, 2002). This

humorous or warm communication style encourages the viewer to believe that the live host is friendly and warm, which helps to narrow the psychological distance between them (Lu et al.,

2016), thereby providing the viewers with an imaginary sense of intimacy and social bond with the live host, even considered the live host to be a friend and companion. On the other hand,

parasocial interaction plays a significant positive mediating role in the relationship between network social presence and emotional, instrumental, and economic support willingness. That is

to say, the network social presence can indirectly affect the viewer’s social support willingness by influencing their parasocial interaction. Specifically, during a live stream, the live

host not only provides the viewer with functional benefits but also creates interactive relationships with viewers which can help create emotional experiences such as setting off the

atmosphere, arising resonance, enhancing the authenticity and intimacy of the communication, and improving the interactive experience between the viewer and host. The stable parasocial

interaction as a spiritual relationship model can be maintained to enhance the viewer’s willingness to provide support for the live host (Horton and Whol, 1956). Significantly, this study

also examines the emotional response of the live viewer and investigates whether the mediating effect of parasocial interaction on the relationship between network social presence and social

support willingness is moderated by emotional response. Previous studies largely focus on the direct effect of emotional response on individual behavior (Zhang et al., 2012; Klein et al.,

2009). There is a gap in the literature regarding whether emotional response indirectly affects social support willingness through parasocial interactions. This study offers new insights

that emotional response only moderates the relationship between parasocial interaction and instrumental support willingness. Specifically, emotional response strengthens the relationship

between parasocial interaction and instrumental support willingness. In the live streaming environment, the interaction between the live host and the viewer makes the viewer feel as if they

are close friends in real life (Horton and Wohl, 1956), arousing the viewer’s emotional pleasure, and thus enhancing the willingness and motivation to provide instrumental support.

Nevertheless, emotional response has no moderating effect on the relationship between parasocial interaction and emotional and economic support willingness. The first reason for this lack of

a moderating effect may be that, for the sake of performance, the live host is often oriented by task interaction; that is, the host needs to interact with multiple viewers synchronously,

utilizing the limited live time to complete the explanation and promotion of goods, ignoring the establishment of emotional social interaction with the viewer. This one-to-many asymmetric

communication interaction mode weakens the real-time interaction experience of some viewers and reduces the trust of the viewer (Yu et al., 2018; Chen et al., 2017). Second, live streaming

is unlike other online community activities with reciprocal support (Introne et al., 2016). The live host does not provide economic or instrumental feedback to the viewer. Third, Chinese

internet users have been accustomed to a “free” online consumption mode for a long time, and many viewers instinctively have a resistance to the reward and gift-giving mechanism in the live

platform. The interaction loss, one-way payment and free inertia make it difficult for emotional response to play a moderating role in the process of parasocial interaction affecting

emotional and economic support willingness. RESEARCH IMPLICATIONS THEORETICAL IMPLICATIONS This study has three theoretical contributions. Firstly, social support willingness is a

multidimensional structure. Currently, academia has not reached consensus on these dimensions, but research has consistently shown that there is a difference between tangible support (such

as instrumental assistance, goods, services, money) and intangible support (such as emotional care, information; Barrera, 1986; Weiss, 1974). Around webcasting, our study has supported

social support willingness as a three-dimensional structure, including emotional support willingness, instrumental support willingness, and economic support willingness. One advantage of a

multidimensional conceptualization of social support intention is the ability to better capture the different behavioral intentions of live viewers, which overcomes the limitations of

viewing social support intention as a one-dimensional structure. Moreover, previous research on the social support willingness of live viewers has mainly focused on economic support, such as

consumer purchase willingness (Huang et al., 2022; Chen et al., 2018) and gift-giving behavior (Zhou et al., 2019) in online live streaming, but little progress has been made in studying

the factors that affect the instrumental and emotional support willingness of live viewers. The findings of this study provide a deeper understanding of what factors affect the three

dimensions of social support willingness of live viewers. Therefore, our research complements existing research on the viewer’s social support willingness in the online live streaming

environment. Secondly, this study provides a new path for the study of network social presence. As an emerging type of social television, live streaming is more attractive than other media

such as video games, online shopping, and online broadcasting because it provides both entertainment and immersive experiences (Haimson and Tang, 2017). Past research has shown that network

social presence is an important factor affecting quasi-social interaction (Kim and Song, 2016; Lee, 2013) and has also confirmed the mediating role of parasocial interaction between social

presence and intention of financial supportive action offline (Shin et al., 2019). However, the mediating role of parasocial interaction between network social presence and online social

support willingness is not explored. In online consumption research, network social presence is considered a powerful predictor of consumer behavioral willingness (Huang et al., 2022;

Algharabat, 2018), but few studies have explored the relationship between network social presence and online nonmonetary support willingness. Therefore, this study links network social

presence and parasocial interaction, confirming the positive relationship between the two, echoing previous research, and also confirming that parasocial interaction plays a mediating role

between network social presence and online social support willingness. In addition, this study explores the monetary and nonmonetary support driven by network social presence and finds that

network social presence can enhance the viewing experience in live streaming situations. Network social presence impacts the viewer’s willingness to support the host in terms of emotions,

tools, and economics, thereby echoing the role of network social presence in controlling, engaging, and cognitively and emotionally arousing the audience in an intermediary environment,

immersing the audience in it, and thus promoting audience participation (Mollen and Wilson, 2010). This study combines the discussion of network social presence in the field of media and

consumer behavior, expands the research and application level of this concept, and constructs a complete pathway, providing a theoretical reference for subsequent research on online live

streaming. Thirdly, this study takes a step forward by empirically investigating the regulatory role of emotional responses in these relationships. In the past, most studies on emotional

response have focused on exploring its direct mechanism of action on individual behavior (Zhang et al., 2012; Klein et al., 2009); few studies have examined whether emotional response can

exert an indirect impact on social support willingness through parasocial interaction. This study is the first attempt to provide empirical evidence on the impact of emotional response on

the relationship between quasi-social interaction and the social support willingness of live viewers in online live streaming settings, providing guidance for future research in this field.

The results indicate that emotional response regulates the relationship between parasocial interaction and instrumental support willingness. This finding not only helps to answer the

question of how parasocial interaction enhances the instrumental support willingness of live viewers but also helps to further enrich the theoretical implications and application fields of

emotional response. PRACTICAL IMPLICATIONS This study provides important practical guidance for live host and live streaming platforms. The results indicate that network social presence can

effectively induce the perception of parasocial interaction and emotional response of live viewers, thereby enhancing their social support willingness. However, improving the network social

presence, parasocial interaction, and emotional response in live streaming requires multiple efforts. From the perspective of live hosts, live hosts should adopt effective, interactive, and

collaborative strategies to enhance the live viewer’s network social presence, parasocial interaction, and emotional response (Rourke et al., 1999). Firstly, live hosts should adopt

emotional strategies. The live hosts can act as an acquaintance and adopt emotional language, such as “My dear family”, “Babies”, and other intimate terms, to quickly establish a stronger

and intimate relationship with the audience through this kind of familial, friendly, and greeting language (Xie and Fang, 2021). In addition,the live host can also engage in daily care,

greetings, emotional sharing, and confiding intimate communication in a heart to heart mode through live room chats (Xie and Fang, 2021), promoting emotional connection with the audience,

thereby increasing the viewer’s retention time and social support willingness in the live room. Secondly, to increase viewers’ perception of online live streaming, live hosts should

communicate with viewers in an interaction-oriented manner. Live content is not just a personal talk show for the live host, but also shaped by the viewer’s responses and feedback (Hamilton

et al., 2014). Moreover, discussing familiar topics can also help improve intimacy (Argyle, Cook (1975)), which is an important factor affecting the viewer’s network social presence.

Therefore, the live host should increase real-time interaction with the viewer during online live streaming, focusing on real-time feedback on viewer behavior (such as entering live

streaming, liking, following, forwarding, commenting, and purchasing). For example, the live host can view the comments of the viewers in real time, ask or respond to targeted questions,

understand the viewer’s surrounding environment and hobbies through viewer descriptions, and appropriately adjust the live content to create attractive content that meets viewer’s

expectations, increasing their interest and enhancing interactive effects, and further enhancing viewer’s network social presence and parasocial interaction, thereby enhancing their social

support willingness. In addition, the live host can also play the role of “curators” by listening and providing the viewer with multiple opportunities to exchange and share their

understanding and experience, and using various incentive measures to enhance their sense of participation, in order to fully stimulate and guide the viewer’s positive cognitive-emotional

experience. These real-time interactions can drive viewers to better respond to live streaming content and services, ensuring smooth interaction during the live streaming process. The more

interaction with the viewer, the greater the likelihood that they will stay on the live streaming platform because they believe they have a close relationship with the host and other

viewers, and experience a sense of immersion. Finally, the live host should utilize a cohesive strategy, including phatic language and online nicknames that enhance users’ parasocial

interaction experience and convey a sense of connection (Labrecque, 2014), this stable interaction can effectively make viewers feel like they are part of the live streaming platform and

immerse in it. To further enhance the positive effects of social presence communication via social interaction and emotional response, live hosts should improve their personal information

such as their name, gender, and avatar, effectively inducing the viewer’s perception of establishing intimate and personal relationships with the live host. Furthermore, live hosts should

conduct responsive, reciprocal, and back-and-forth conversations to maximize the viewer’s emotional response. From the perspective of live streaming platform operators, the mass

communication nature of online live streaming may not be suitable for promoting direct interaction. Firstly, for live hosts with relatively small numbers of viewers, direct interaction is

still feasible, but for live hosts with large viewers, it is physically impossible for the live host to interact directly with a large viewer simultaneously. To this end, live streaming

platform operators can use both robots and human hosts to help adjust the chat function of the live host. In addition, live streaming platform operators can also optimize the design and

production of live streaming platforms to help their live hosts interact more directly with the viewers. For example, emotion monitoring tools can be established such as facial expression

analysis, audio analysis, and text analysis with the help of artificial intelligence technology to assist in dynamic interaction between live hosts and viewers by displaying viewer emotions

and viewer management suggestions (Chen et al., 2023). Secondly, live streaming, as a new environment that erodes the boundaries of time and space, should give full play to its unique

advantages of social and life attributes, promote interaction between viewers and increase their perception of network social presence. Danmaku system is an effective tool for promoting

communication and interaction on a live streaming platform. When watching the live broadcast, viewers can publish and read Danmaku comments that update on the screen in real time, which

helps viewers create a shared viewing experience (Zhou et al., 2019). The viewers can also trigger heated discussions through Danmaku to improve their sense of social presence with other

viewers, create a higher level of immersion, and ignore the existence of time, thereby affecting their level of arousal, effectively promoting viewer online gift giving behavior. To do this,

engineers can highlight debate content or words related to excitement in the bullet screen to enhance the viewer’s network presence and emotional response (Zhou et al., 2019). Developing

real-time interactive voice functions, such as virtual conference applications such as Zoom and VooV meeting, may bring better co-awareness and positive emotional arousal. Thirdly, the live

streaming platform can reward the viewer with points or create identity tags and identity symbols for the active interactive viewer to encourage them to interact with other viewers on the

platform, so as to generate a stronger sense of network social presence and social support willingness, which will also enhance viewer’s continuous use of the live streaming platform.

Finally, live streaming platform operators should improve efforts to increase personalization, provide customized services, and provide different types of live streaming content to meet the

social and psychological needs of different viewers, thereby significantly enhancing the viewer’s immersive experience and generating positive emotional resonance. For example, live

streaming platform operators can classify viewers by mapping click streams to different types of visits, and provide personalized information for different types of viewers based on their

access goals (Tam and Ho, 2006). LIMITATION AND FUTURE RESEARCH DIRECTIONS This study is subject to certain limitations that require further investigation, which may present opportunities

for future research. Firstly, this study uses a questionnaire survey method to conduct a preliminary understanding of the social support willingness of Chinese live viewers to live hosts and

determine the pathway of increasing the social support willingness of live viewers towards live hosts. However, the cross-sectional nature of this study prevents us from reaching clear

conclusions about the causal relationship between the analyzed variables. Although most previous studies have adopted a retrospective questionnaire survey method to explore the relationship

between network social presence and social support willingness (such as Huang et al., 2022; Algharabat, 2018), such retrospective questionnaire surveys still cannot fully reflect the series

of psychological changes of respondents while watching live streaming. The unique immediacy, dynamism, and interactivity of live casts are more suitable parameters for testing the

relationship between online presence and social support willingness through real-time and direct communication between media figures and viewers. Therefore, future research can use

experimental or observational methods to further explore the causal relationship between network social presence and social support willingness, also reducing commonly used variables by

collecting data from different time periods and setting reference items. Secondly, the AVE value of network social presence is only 0.506. In the future, the measurement and application of

network social presence can be further deepened. For example, measurement can be divided into “co-existence,” “psychological participation,” and “intimacy”; further division could include

“emotional presence” and “cognitive presence” (Shen and Khalifa, 2008). Such multiple consideration can enhance the accuracy of the research results and contribute to finding further

mediators or moderators that affect social support willingness, to find more possible influence pathways of network social presence and social support willingness. Finally, this study did

not make a more detailed classification of live streaming, only measuring the influence mechanism of the viewer’s willingness to support the live host in the general viewing situation.

However, the differences in the live content, the characteristics of the live host and the live situation create different degrees of influence on the viewer’s decision and behavior (Zhou et

al., 2019). Therefore, given that different types of live streaming (such as travel live streaming, gaming live streaming, shopping live streaming, and chat live streaming) meet the

different needs of viewers, future research can investigate factors that can display the uniqueness of the live streaming environment, to summarize and obtain more granular findings in

different live streaming environments. For example, product category and gender may affect audience behavior in a live streaming environment. Currently, taking Taobao as an example, the most

popular live streaming product categories are clothing, shoes, accessories, jewelry, cosmetics, and household goods, which attract more female viewers (Xu, Wu, and Li, 2020). Future

research on Taobao can be designed and studied for female audiences to gain a more comprehensive understanding of the social support willingness mechanism of female Taobao users. DATA

AVAILABILITY The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due to ongoing research and analysis, but are available from the corresponding

author on reasonable request. REFERENCES * Algharabat RS (2018) The role of telepresence and user engagement in co-creation value and purchase intention: Online retail context. J Internet

Commer 17(1):1–25. https://doi.org/10.1080/15332861.2017.1422667 Article Google Scholar * Almaqtari FA, Farhan NHS, Al-Hattami HM, Elsheikh T (2023) The moderating role of information

technology governance in the relationship between board characteristics and continuity management during the Covid-19 pandemic in an emerging economy. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 10(96):1–16.

https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-023-01552-x Article Google Scholar * Argyle M, Cook M (1975) Gaze and Mutual Gaze. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, MA Google Scholar * Barak A,

Boniel-Nissim M, Suler J (2008) Fostering empowerment in online support groups. Comput Hum Behav 24(5):1867–1883. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2008.02.004 Article Google Scholar * Barrera

M (1986) Distinctions between social support concepts, measures, and models. Am J Commun Psychol 14(4):413–445. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00922627 Article Google Scholar * Chan JT (2020)

Snowball sampling and sample selection in a social network. In: The Econometrics of Networks. Emerald Publishing Limited * Cheah JH, Sarstedt M, Ringle CM, Ramayah T, Ting H (2018)

Convergent Validity Assessment of Formatively Measured Constructs in PLS-SEM: On Using Single-Item versus Multi-Item Measures in Redundancy Analyses. J Int Consum Mark 30(11):3192–3210.

https://doi.org/10.1108/ijchm-10-2017-0649 Article Google Scholar * Cheikh-Ammar M, Barki H (2016) The influence of social presence, social exchange and feedback features on SNS continuous

use. J Organ End User Com 28(2):33–52. https://doi.org/10.4018/joeuc.2016040103 Article Google Scholar * Chen LR, Chen FS, Chen DF (2023) Effect of Social Presence toward Livestream

E-Commerce on Consumers’ Purchase Intention. Sustainability-basel 15(4):3571. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15043571 Article MathSciNet Google Scholar * Chen CC, Lin YC (2018) What drives

live-stream usage intention? The perspectives of flow, entertainment, social interaction, and endorsement. Telemat Inform 35(1):293–303. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tele.2017.12.003 Article

MathSciNet Google Scholar * Chen TY, Yeh TL, Lee FY (2021) The impact of Internet celebrity characteristics on followers' impulse purchase behavior: the mediation of attachment and

parasocial interaction. J Res Interact Mark 15:483–501. https://doi.org/10.1108/JRIM-09-2020-0183 Article Google Scholar * Chen Y, Lu S, Yao D (2017) The Impact of Audience Size on Viewer

Engagement in Live Streaming: Evidence from A Field Experiment. Working Paper * Cheung CM, Shen XL, Lee ZW, Chan TK (2015) Promoting sales of online games through customer engagement.

Electron Commer R A 14(4):241–250. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.elerap.2015.03.001 Article Google Scholar * Choi S, Kim I, Cha K, Suh YK, Kim KH (2019) Travelers’ parasocial interactions in

online travel communities. J Travel Tour Mark 8(36):888–904. https://doi.org/10.1080/10548408.2019.1657053 Article Google Scholar * Choi J, Ok C, Choi S (2016) Outcomes of destination

marketing organization website navigation: The role of telepresence. J Travel Tour Mark 33(1):46–62. https://doi.org/10.1080/10548408.2015.1024913 Article Google Scholar * CNNIC (2022)

2022 Statistical report on Internet development in China. http://www.gov.cn/xinwen/2022-09/01/content_5707695.htm * Cohen J (2004) Parasocial break-up from favorite television characters:

The role of attachment styles and relationship intensity. J Soc Pers Relat 21(2):187–202. https://doi.org/10.1177/0265407504041374 Article Google Scholar * Cummings JJ, Wertz EE (2022)

Capturing social presence: concept explication through an empirical analysis of social presence measures. J Comput-Mediat Comm 28(1):1–14. https://doi.org/10.1093/jcmc/zmac027 Article CAS

Google Scholar * Cunningham S, Craig D, Lv J (2019) China’s livestreaming industry: platforms, politics, and precarity. Int J Culteal Stud 22(6):719–736.

https://doi.org/10.1177/1367877919834942 Article Google Scholar * Chang DR, Kim Q (2022) A study on the effects of background film music valence on para-social interaction and consumer

attitudes toward social enterprises. J Bus Res 142:165–175. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2021.12.050 Article Google Scholar * Dale C, Pymm JM (2009) Podagogy: The iPod as a learning

technology. Act Learn High Educ 10(1):84–96. https://doi.org/10.1177/1469787408100197 Article Google Scholar * Drolet AL, Morrison DG (2001) Do We Really Need Multiple-Item Measures in

Service Research? J Serv Res-us 3(3):196–204. https://doi.org/10.1177/109467050133001 Article Google Scholar * Ellison NB, Vitak J, Gray R, Lampe C (2014) Cultivating social resources on

social network sites: Facebook relationship maintenance behaviors and their role in social capital processes. J Comput-Mediat Comm 19(4):855–870. 0.1111/jcc4.12078 Article Google Scholar *

Eroglu SA, Machleit KA, Davis LM (2003) Empirical Testing of a Model of Online Store Atmospherics and Shopper Responses. Psychol Market 20(2):139–150. https://doi.org/10.1002/mar.10064

Article Google Scholar * Fornell C, Larcker DF (1981) Structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error: Algebra and statistics. J Marketing Res 18(3):382–388.

https://doi.org/10.1177/002224378101800313 Article Google Scholar * Gavriel-Fried B, Ronen T (2016) Positive emotions as a moderator of the associations between self-control and social

support among adolescents with risk behaviors. Int J Ment Health Ad 14(2):121–134. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-015-9580-z Article Google Scholar * Gao W, Liu Z, Li J (2017) How does

Social Presence Influence SNS Addiction? A Belongingness Theory Perspective. Comput Hum Behav 77:347–355. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2017.09.002 Article Google Scholar * Haimson OL,Tang

JC, (2017) What makes live events engaging on Facebook live, periscope, and snapchat. Proceedings of the 2017 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems.

17:48-60.10.1145/3025453.3025642 * Hair J, Bush R, Ortinau D (2006) Marketing Research: Within a Changing Information Environment, third ed. McGraw-Hill, New York * Hair JF, Risher JF,

Sarstedt M, Ringle CM (2019) When to Use and How to Report the Results of PLS-SEM. Eur Bus Rev 31(1):2–24. https://doi.org/10.1108/ebr-11-2018-0203 Article Google Scholar * Hamilton WA,

Garretson O, & Kerne A (2014) Streaming on twitch: Fostering participatory communities of play within live mixed media. Paper presented at the CHI’14 proceedings of the SIGCHI conference

on human factors in computing systems, New York * Han S, Min J, Lee H (2015) Antecedents of social presence and gratification of social connection needs in SNS: a study of Twitter users and

their mobile and non-mobile usage. Int J Inform Manage 35(4):459–471. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2015.04.004 Article Google Scholar * Hassanein K, Head M (2007) Manipulating

perceived social presence through the web interface and its impact on attitude towards online shopping. Int J Hum-Comput St 65(8):689–708. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhcs.2006.11.018 Article

Google Scholar * Hilvert-Bruce Z, Neill JT, Sjöblom M, Hamari J (2018) Social motivations of live-streaming viewer engagement on Twitch. Comput Hum Behav 84:58–67.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2018.02.013 Article Google Scholar * Hoffman MA, Ushpiz V, Levy-shiff R (1988) Social support and self-esteem in adolescence. J. Youth Adolescence

17(4):307–316. https://doi.org/10.1007/bf01537672 Article CAS Google Scholar * Horton D, Strauss A (1957) Interaction in audience-participation shows. Am J Sociol 62:579–587.

https://doi.org/10.1086/222106 Article Google Scholar * Horton D, Whol RR (1956) Mass Communication and Para-Social Interaction: Observations on intimacy at a distance. Psychiatry

19(3):215–229. https://doi.org/10.1080/00332747.1956.11023049 Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Hsu CL, Lin JCC, Miao YF (2020) Why are People Loyal to Live Stream Channels? The

Perspectives of Uses and Gratifications and Media Richness Theories. Cyberpsychol Beh Soc N 23:351–356. https://doi.org/10.1089/cyber.2019.0547 Article Google Scholar * Hu M, Zhang M, Wang

Y (2017) Why do audiences choose to keep watching on live video streaming platforms? An explanation of dual identification framework. Comput Hum Behav 75:594–606.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2017.06.006 Article Google Scholar * Huang Z, Zhu Y, Hao A, Deng J (2022) How social presence influences consumer purchase intention in live video commerce:

the mediating role of immersive experience and the moderating role of positive emotions. J Res Interact Mark 1-17. https://doi.org/10.1108/JRIM-01-2022-0009 * iiMediaResearch (2022) 2021